AMAZON multi-meters discounts AMAZON oscilloscope discounts

<< cont. from part 1

1.3 Reliability-Centered Maintenance

One of the enhancements of TPM that "fine tune" it for the Lean Maintenance operating mode is the selective use of several Reliability-Centered Maintenance (RCM) features. In Section 2, it was stated that one of the objectives of lean maintenance was the elimination of unnecessary maintenance; another was maintenance optimization. This is where RCM is "selectively" applied to "fine tune" TPM. RCM is a primary tool applied by the Reliability Engineering group.

RCM was born out of a 1960 FAA/Airline Industry Reliability Program Study that was initiated to respond to rapidly increasing maintenance costs, poor availability and concern over the effectiveness of traditional time-based preventive maintenance. The study centered around challenging the traditional approach to scheduled maintenance programs, which were based on the concept that every item on a piece of complex equipment has a operating time limit at which complete overhaul is necessary to ensure safety and operating reliability.

The generally used definition of RCM is that it is a process used to determine the maintenance requirements of any physical asset in its operating context. Perhaps a more complete, or accurate, definition is that RCM consists of processes used to determine what must be done to ensure that any physical asset continues to do whatever its users want it to do in its present operating context. In strict context, RCM does not concern itself with issues such as labor efficiency or waste elimination. Therefore, if RCM is to be applied in a lean operation, these constraints must be enforced by the TPM process.

There has been a proliferation of maintenance programs calling themselves RCM. In an effort to curtail these "offshoots" of RCM, the Society of Automotive Engineers has developed and issued SAE JA-1011, which provides some degree of standardization for the RCM process. The SAE standard defines the RCM process as asking seven basic questions from which a comprehensive maintenance approach can be defined.

-- What are the functions and associated performance standards of the asset in its present operating context?

-- In what ways can it fail to fulfill its functions?

-- What causes each functional failure?

-- What happens when each failure occurs?

-- In what way does each failure matter?

-- What can be done to predict or prevent each failure?

-- What should be done if a suitable proactive task cannot be found?

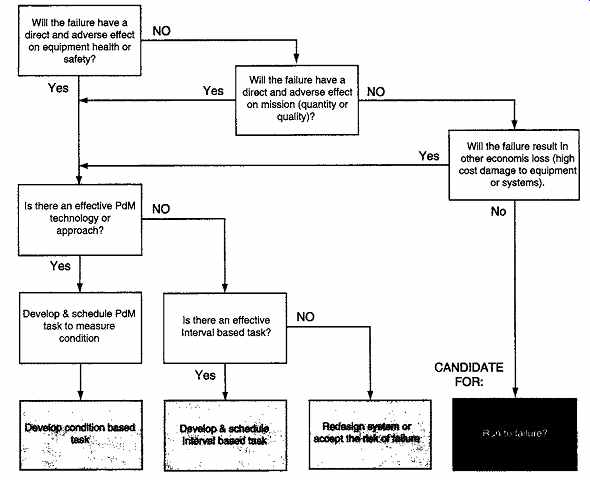

The first four questions constitute a functional Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA) and the last two define the appropriate maintenance approach. The vitally important fifth question determines failure delectability (whether the failure is 'hidden' or 'evident') and whether and in what way safety, the environment or operations are affected. These seven questions can only sensibly be answered by people who know the asset best; this includes maintainers and operators, supplemented by representatives from OEMs. In a full-blown RCM analysis, this group is guided through each step by a competent "facilitator" who is an expert in the RCM process and its application rather than the system expert. In the Lean Maintenance Environment, "full-blown" RCM analysis is usually not necessary, with the possible exception of extreme cost or high potential for severe environmental or safety impact, hence the Lean Maintenance "selective RCM application." Because the Lean Maintenance objectives to be examined are elimination of unnecessary maintenance and maintenance optimization, questions 6 and 7 are the ones of immediate interest. Maintenance analysis is performed to determine the answers. Note that the maintenance analysis process, as illustrated in FIG. 9, has only four possible outcomes:

1. Perform interval (time- or cycle-) based actions, or

2. Perform condition-based actions, or

3. Perform no action and choose to repair following failure, or

4. Determine that no maintenance action will reduce the probability of failure AND that failure is not the chosen outcome (redesign or redundancy).

FIG. 9 Maintenance Analysis Process

Additional responsibilities of Reliability Engineering in the Lean Maintenance Environment include the elimination of unnecessary maintenance activity and maintenance optimization. The responsibilities of Reliability Engineering for the establishment and execution of maintenance optimization using Computerized Maintenance Management Systems (CMMS) Unscheduled and Emergency reports, Planned/Preventive Maintenance reports and Condition Monitoring (CM)/Predictive Maintenance (PdM) analysis include:

-- Develop CM tests and PdM techniques that establish operating parameters relating to equipment performance and condition and gather data.

-- Analyze CMMS reports of completed CdM/PdM/Corrective work orders to determine high-cost areas.

-- Establish methodology for CMMS trending and analysis of all maintenance data to make recommendations for:

1. Changes to PM/CM/PdM frequencies;

2. Changes to Corrective Maintenance criteria;

3. Changes to Overhaul criteria/frequency;

4. Addition/deletion of PM/CM/PdM routines;

5. Establish assessment process to fine-tune the program;

6. Establish performance standards for each piece of equipment;

7. Adjust test and inspection frequencies based on equipment operating (history) experience;

8. Optimize test and inspection methods and introduce effective advanced test and inspection methods;

9. Conduct a periodic review of equipment on the CM/PdM program and delete the equipment no longer requiring CM/PdM;

10. Remove from, or add to, the CM/PdM program that equipment and other items as deemed appropriate;

11. Communicate problems and possible solutions to involved personnel;

12. Control the direction and cost of the CM/PdM program.

The joint FAA/Airline industry study performed in 1960, referred to earlier, revealed that many types of failures could not be prevented, or even reduced, by operating time limit overhauls no matter how extensively they were performed. Two unexpected findings from the 1960 FAA/Airline Industry Reliability Program Study were as follows:

1. Scheduled overhauls had little effect on the overall reliability of a complex item unless the item had a dominant failure mode.

2. There were many items found for which there was no effective form of scheduled maintenance.

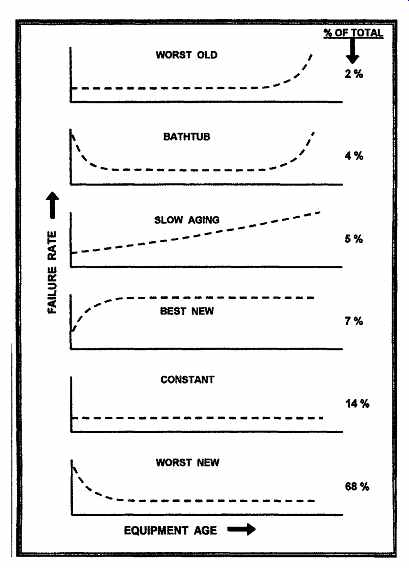

The 1960 study and related studies performed after that initial program indicated that all components do not follow the traditionally accepted "operate reliably then wear out" failure probability. They tend to follow a variety of failure probabilities as illustrated in FIG. 10.

The failure probability distribution must be considered when defining a PM/CM/PdM optimization strategy for equipment. For example, CM is likely to be the maintenance mode of choice for a component whose failure probability is "slow aging." Similarly, fixed frequency overhaul or replacement, or an appropriate PdM technique, is a likely choice for a component whose failure probability is "Best New."

FIG. 10 Failure Probability Distribution Patterns

The Reliability Engineer can employ any of several techniques for determining optimum frequencies for maintenance actions including statistical determination, Condition Monitoring (CM) and PdM Analyses, and analysis of equipment history records. The latter technique, analysis of equipment history records, is made vastly easier by effectively implemented CMMS or Enterprise Asset Management (EAM) systems.

Ensuring the completeness and accuracy of the historical data archived in CMMS or EAM is under the purview of Maintenance Planning and Scheduling.

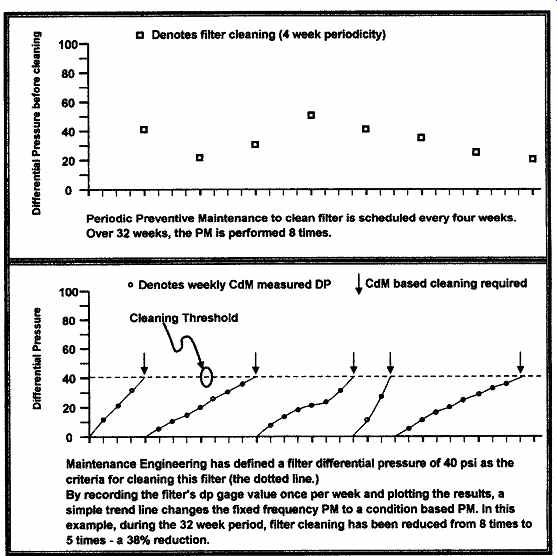

CM is differentiated from PdM primarily by the use of in-place instrumentation and in-place testing (self-test) capabilities to gather data indicative of component, equipment or system condition. In its simplest form, condition monitoring can employ procedural documentation that provides an area for recording readings of installed meters and gauges when they are pertinent to the preventive maintenance task being performed. Such data can provide a simple means for evaluating the effectiveness of the maintenance and optimizing scheduling. An example of the most basic level of CM and its use in maintenance optimization is illustrated in FIG. 11.

FIG. 11 Application of CM to Maintenance Optimization

A major responsibility of the reliability engineer is that of eliminating recurring failures. He accomplishes this through the application of Root Cause Failure Analysis (RCFA). Failures are seldom planned for and usually surprise both maintenance and production personnel and they nearly always result in lost production. Finding the root cause of a failure provides you with a solvable problem removing the mystery of why equipment failed. Once the root cause is identified, a "fix" can be developed and implemented.

There are five basic phases in performing a RCFA: Phase I (data collection): It is important to begin the data collection phase of root cause analysis immediately following the occurrence identification to ensure that data are not lost. (Without compromising safety or recovery, data should be collected even during an occurrence.) The information that should be collected consists of conditions before, during, and after the failure occurrence; personnel involvement (including actions taken); environmental factors and other information having relevance to the occurrence.

Phase H (assessment): Any root cause analysis method may be used that includes the following steps:

1. Identify the problem.

2. Determine the significance of the problem.

3. Identify the causes (conditions or actions) immediately preceding and surrounding the problem.

Identify the reasons why the causes in the preceding step existed, working back to the root cause (the fundamental reason that, if corrected, will prevent recurrence of these and similar occurrences throughout the facility). This root cause is the stopping point in the assessment phase.

Phase III (corrective actions): By implementing effective corrective actions for each cause reduces the probability that a problem will recur and improves reliability and safety.

Phase IV (inform): Entering the RCFA results on the appropriate RCFA worksheet or report form is part of the inform process. Also included is discussion and explanation of the results of the analysis, including corrective actions, with management and personnel involved in the failure occurrence.

RCFA reporting should be as complete as possible.

Phase V (follow-up): Follow-up includes determining if corrective action has been effective in resolving problems. An effectiveness review is essential to ensure that corrective actions have been implemented and that they are preventing failure recurrence.

There are many methods available for performing RCFA; selecting the right method for RCFA can speed the entire process up so that you can proceed to the "fix" stage more quickly. Some of the more commonly used RCFA methods include:

-- Ishikawa method of cause and effect analysis (fishbone diagramming);

-- Fault tree analysis

-- Sequence of events analysis

-- Events and causal factor analysis;

-- Change analysis;

-- Barrier analysis;

-- Management oversight and risk tree (MORT);

-- Human performance evaluation;

-- Kepner-Tregoe problem solving and decision making.

1.3.1 Incorporating Work Planning

Incorporating work planning into the maintenance organization first requires pre-preparation to ensure the requisite tools and conditions are in place to facilitate the efforts of work planners. Correctly and efficiently performing the planning function requires management to provide adequate guidance on the level of control necessary to ensure consistent quality maintenance of plant equipment. The requirements to provide procedures for safety-related equipment and equipment important to plant safety should be clearly spelled out in plant standard operating procedures (SOPs), Safety Instructions and related plant policy documentation.

Large disparities exist throughout industry in the level of detail and procedural guidance provided to maintenance personnel for performing work on plant equipment. Many plants rely heavily on "presumed trade skills" but they have not assessed the actual skill levels of their personnel. For example, it is commonly accepted that an electrician possesses the necessary skills to install wiring lugs; however, the manufacturing industry as a whole, continues to have problems with loose wiring.

Presumed trade skills should be given careful consideration when preparing planned work packages, job requests, and work instructions to ensure that additional training, worker qualifications, or job oversight/quality control are included, if required. For example, work instructions for non-facility contractors may need to include more detail, inspections, or supervisory guidance.

To reduce problems caused by inadequate instructions being provided to the tradesperson, managers should establish minimum levels of trade proficiency and implement training programs to ensure that the expected trade skill levels are developed and maintained. Maintenance Supervisors should be responsible for assessing skill levels and identifying training requirements. Deficiencies identified through daily activities, industry experience, or root cause analysis may result in the identification of additional training needs to maintain or upgrade this skill level. For work beyond expected skills, more detailed work instructions will need to be provided to the tradesperson.

"Presumed trade skills" are work skills that should be common knowledge (for the skill level designated) to the individual performing the work.

The skill level of every maintenance employee should be assessed.

Maintenance trades should then be formally trained to advance to successively higher skill levels. By means of a qualification and certification process tied to the training program, certification as qualified to perform at each skill level should be a formalized process. Unqualified maintenance workers should be assigned to work under the supervision of a qualified individual.

Without adequately defined and controlled trade skills, the planner's function is rendered at least 10-fold more complex and difficult. Given ill-defined trade skills, each work plan will need to be tailored to the individual assigned to the work, and specific individuals will need to be assigned to the work before the planner can complete the work plan instructions. Such a dichotomy is often referred to as a "self-eating watermelon." Where the planning function "fits" within the maintenance operation and what mechanisms exist to enhance the planner's effectiveness should be well defined if the work planning function is to realize all of the beneficial effects that are possible. Work planning encompasses the coordination of various input resources (material, labor, and equipment), as required, to complete each job in an orderly manner and at least overall cost. Supervisors are relieved of much indirect activity, enabling them to spend their time in the plant, overseeing the trade crews while the planning function is performed by quasi-managerial personnel. Just how this will be accomplished requires decisions concerning

-- where will the planning group fit into the overall organization?

-- who will be responsible for establishing and administering the program?

Planning installations that fail often do so due to insufficient attention to these details. The importance of incorporating this vital function into the overall facility strategy is missed. The planning function should report through the maintenance staff at least one level above the first maintenance supervisor level supported on a day-to-day basis. If the planning function reports to the first line maintenance supervisor, there is a tendency to use the planner for work other than planning. The planner's job should be rated at least on a par with the first line supervisor, otherwise problems will arise regarding the planner's authority.

To gain the favorable attitude of both the craftsman and maintenance supervisors, active program support by plant and maintenance management is essential. By placing the planning group directly under the supervision of maintenance management and creating planner job positions equivalent in grade to first line supervision, functional importance is emphasized.

If the planning function is positioned too low in the organization, it does not receive proper management attention when decisions are required.

Therefore, if there are more than four positions in the maintenance control organization (including planners, schedulers, material coordinators, clerks, and dispatchers), they should report through a maintenance control manager to bring coordination, functional discipline and integrity, as well as managerial acumen and clout to the maintenance services group. Such coordination is not always performed effectively by the maintenance manager who is consumed more by direction of first line supervision, budgetary control, and response to upper management. When the burden of formal planning and scheduling is added, it often becomes too much for the maintenance manager to address adequately.

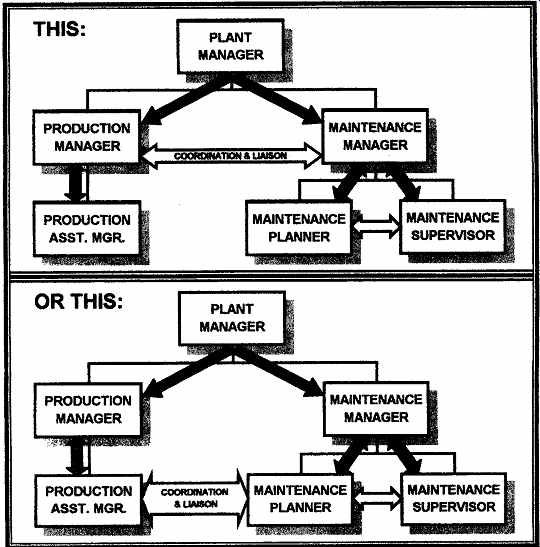

A conscious decision is necessary with regard to working liaisons. Is the planner going to interface directly with the Operations department, or is that relationship to be a function of the maintenance management level to which planning reports? FIG. 12 depicts the two options:

1. Given indirect liaison, the planner supports only the maintenance manager. He is, in effect, a staff assistant to the maintenance manager.

All other liaison is accomplished within the level (both within maintenance and with operations).

2. Given direct liaison, the planner is supporting maintenance management and supervision as well as the operating unit to a maximum degree. This is in keeping with the current team concepts and individual participation and involvement precepts.

Direct liaison is the preferred mode!

FIG. 12 Indirect and Direct Liaison

1.3.2 Planning and Scheduling: Defining the Role

It seems that everyone today is looking for some ways to improve maintenance. As maintenance assumes an increasing share of manufacturing conversion and upgrade costs, everyone involved wants to ensure that every dollar spent on maintenance is worthwhile. The search for maintenance improvements is centered on finding a program, concept, or approach that will improve the productivity of maintenance labor while at the same time improving production equipment reliability, availability, and productivity.

The search must be successful if the manufacturing sector of the economy is to remain viable and competitive.

The "pot-of-gold" can be elusive but finding it begins with sound work planning. Without proper planning and scheduling, maintenance, at best is haphazard; at worst, it is costly and ineffective. The comprehensiveness and sophistication of maintenance Planning and Scheduling is the primary determinant of the level of output and of the degree of productivity of maintenance workers.

Maintenance Organizations everywhere are responsible for ensuring that the operational capacity is met for the enterprise they support. Every element of the organization becomes conscious of maintenance, if not maintenance-conscious, whenever the maintenance function is not being performed properly or efficiently. Unsafe operations, production stoppages, unacceptable quality, and the loss of heat, light, and other utilities will not go undiscovered for very long.

Within the increasing visibility of the maintenance function, it is the area of Maintenance Planning and Scheduling where the greatest benefits can be derived.

Well-planned, properly scheduled, and effectively communicated jobs can be performed more efficiently, at lower cost, less disturbing to operations, at higher quality, with greater job satisfaction and higher organizational morale than jobs performed without proper planning and preparation.

In the long term, more work is also completed more promptly, thereby increasing customer service. While the foregoing may be self-evident, there remains a significant number of manufacturing and process plants that neither practice nor understand effective maintenance planning and scheduling. Sound work planning is a prerequisite for effective performance of the maintenance mission. It is the hub of maintenance management.

Maintenance information flows in and maintenance information flows out.

Planning cannot be outside the mainstream, it must be integral and central to the maintenance operation.

The primary objective of work planning is to identify all technical and administrative requirements for a work activity and to provide the materials,

tools, and support activities needed to perform the work. These items should be provided to tradespersons in an easy-to-use, complete work package.

Effective planning should help ensure that consistent, quality maintenance activities are conducted safely, correctly, and within the allotted time duration. When coupled with an effective scheduling and coordination methodology, delays in performing plant maintenance should be eliminated.

Work planning is an evolutionary process that should be periodically assessed through field observation of work being performed and direct feedback from the tradesperson to the planners. An effective planning program should contain the following key elements:

-- management commitment, overview, and support to ensure success of the program;

-- management direction to ensure appropriate level of detailed work instructions is developed and provided;

-- consistency in planning between disciplines to avoid confusion and frustration of work groups;

-- thorough reviews by experienced individuals of products produced by the planning group to minimize and eliminate errors;

-- feedback from tradespersons and supervisors to facilitate future planning activities;

-- use of job history for establishing standard job durations, parts, and consumables for repetitive jobs.

2. TPM-RCM-LEAN ORGANIZATIONAL CONSIDERATIONS AND CHOICES

As stated earlier, the combination maintenance and production "team" style of organization is the preferred style for effective TPM execution. How does the introduction of selected RCM techniques affect this arrangement? RCM was originally developed for the aircraft industry where "basic equipment conditions" (no looseness, contamination, or lubrication problems) are mandatory, and where operators' (pilots) skill level, behavior, and training are of a high standard. Unfortunately, in most manufacturing operations that have not implemented TPM, these "basic equipment conditions" and operator skill and behavior levels do not exist. These conditions would almost certainly undermine the success of any RCM application. The introduction of RCM into a TPM environment as a Lean Maintenance element, however, is accorded a greater chance for success because in TPM (a) "basic equipment conditions" are established, (b) equipment-competent operators are developed, (c) combined team members exhibit a posture of stewardship over systems/equipment, and (d) Maintenance Engineering is established for acceptance of "Reliability" Engineering role.

Other considerations for organization of the Maintenance Operation and the Planning and Scheduling function revolve primarily around plant size and combined maintenance/operations team assignment criteria. In the smallest manufacturing operations, there may only be a single person assigned to the planning and scheduling arm of the Maintenance Organization. That person would therefore be responsible for all planning operations, including material identification and staging, work instructions, safety and environmental precautions, and other planning functions. In addition, he or she would be responsible for identifying labor resources, liaison/coordination between maintenance and operations, scheduling and coordination meetings, and work order management, including the maintenance of equipment history. As you can see, these are a lot of responsibilities. Some individual functions of the overall maintenance planning and scheduling process may actually be performed by another individual (e.g., material ID and staging, storeroom personnel; work order data recording, IT or office administrative personnel, etc.) but the lone Planner/Scheduler must retain oversight and control of any functions performed by other personnel.

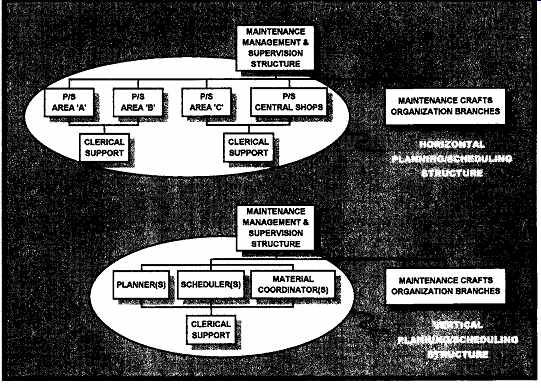

In small, but not the smallest as just cited, manufacturing plants, a horizontal arrangement is the norm. The horizontal, across facility, organizational structure normally utilizes one Planner/Scheduler performing planning, scheduling, material coordination, and operating liaison for all maintenance work associated with one or more production areas, or for one or more central trade groups. An alternative in large organizations is vertical segregation of planners, schedulers, and material coordinators. The selection of structure is often predicated upon available skills. Planning requires more trade knowledge' than scheduling. The latter (vertical) structure can conserve planning capability. Similarly, when the material management system is complex and system knowledge is limited, the material coordinator position should be considered. In either case, it should be centralized to preserve independence. The basic horizontal and vertical organization structures are illustrated in FIG. 13.

FIG. 13 Horizontal and Vertical P/S Organization Structures

Additional choices in structuring the Maintenance Operation in general, and the Planning and Scheduling function in particular, are all predicated on the complexity of the manufacturing operation and its size (magnitude and diversity of operating systems/equipment). Consolidation of specific functions may be desired in order to maintain adequate control as well as to perform the function effectively. An example would be a Material Control Supervisor, who provides direct oversight of individual material coordinators within each of the Planning/Scheduling teams.

2.1 Where Does the Planner Fit?

It was pointed out earlier that the Maintenance Planner should be on par with the first level maintenance supervisor for whom he or she is planning.

Depending again on the size and structure of the manufacturing operation and the maintenance organization, it is strongly recommended that the Maintenance Planner report to the Maintenance Manager or a Maintenance Control Supervisor. In part, this is due to the pivotal role of the planner relative to equipment reliability assurance and in part to the required attributes and knowledge level of the planner. At the same time, it is necessary to consider the roles of others in order to establish where planner responsibility ends and responsibilities of others begin. To be effective, Maintenance Planners need

-- recognition that they are planners, not maintenance supervisors; to be a recognized part of the maintenance team; commitment from maintenance and operation management to hold structured backlog review sessions to establish priorities for daily, weekly, down day, and major outage work;

-- sufficient lead-time on jobs to plan properly and for getting adequate labor resources;

-- to be continuously kept advised on maintenance resource levels;

-- to have their relationships with maintenance superintendents and supervisors and with operations clearly defined;

-- to have work-requests written by requesters with adequate information and identification;

-- an adequate place to work in;

-- adequate computer support for developing a comprehensive planning database;

-- adequate purchasing support so the planner need only identify required purchases and prepare the necessary purchase requisition, and need not do sourcing, purchasing, purchase order preparation, and delivery expediting;

-- adequate storeroom support so the planner need only identify required withdrawals and prepare the necessary stores requisitions, and need not do stock picking, job kitting, and order staging;

-- adequate receiving support so that the planner is reliably alerted when purchased items are received;

-- adequate reliability engineering support so the planner does not have to develop standard operating and safety procedures, and does not have to devote time on engineering attention to recurring maintenance problems;

-- cooperation from maintenance supervisors, tradespersons, and operating supervisors in the effective use and application of efforts put into a meaningful planning package;

-- feedback from maintenance supervisors and operating supervisors regarding specific shortfalls in planning packages in order to facilitate future improvements;

-- feedback from maintenance supervisors regarding compliance with and exceptions to the weekly plan.

The next and obvious question is, due to the planner's pivotal role, degree of responsibility and high level of maintenance knowledge required, just who is the appropriate person to assign to the planner function? Under all circumstances, whenever maintenance is performed, it is planned. However, the important questions are: who is doing the planning, when they are doing it, to what level of detail, and how well. Frequently, the wrong person does little planning, at the wrong time, and usually under the pressure of a reactive maintenance environment.

Tradespersons, supervisors, and planners all contribute to the planning process. However, the assignment of para-professionals to the bulk of the planning process is the preferred solution. Job preparation should be a staff function, thereby fleeing supervisors and tradespersons, which are line functions, to concentrate their efforts upon the separate duty of job execution.

Planning and execution require different skills. A combination of these skills in one person is the exception rather than the rule.

Separation of planning from execution has long been a rule of good organizational structure. Manufacturing supervision is usually supported by strong staff support groups providing the specialized functions of production planning, scheduling and control; methods, procedures and standards; product quality inspection; operator training; cost control; and inventory management.

2.1.1 Erroneous Thinking

Unfortunately, with the arrival of "world-class" philosophies, support functions, and their associated staff (such as maintenance planning) are being drastically reduced in exchange for increased worker involvement, which often includes the absorption of traditional staff duties into the job routines of "work teams." This provides a new argument for those managers with poor understanding of, and appreciation for, the resources required to provide effective maintenance support of operational and production plans and objectives. This approach deprives the Maintenance Operation of an adequate planning function on the grounds that creation or continuation of the function runs counter to modern principles of human behavior. This is based on thinking that, when formal planning (as a separate and distinct function) is eliminated, the task of job preparation and decision making is forced down to the lowest organizational level possible (i.e., the tradesperson). Because this appears to be consistent with TPM and Lean Maintenance concepts of increased worker involvement and self-direction, it is thought that the tradesperson who plans his or her own work is more motivated and therefore more productive.

2.1.2 The Reality

The real objectives of increased worker involvement and self-direction postulated by TPM and Lean Maintenance theory are meant to be focused within the line functions of equipment operation and maintenance. When technicians are engaged in planning, they are not executing productive work in the "Lean" fashion and they are not adding value to the production process. Furthermore, people preparing for their own work efforts are less successful than the para-professional in the efficient organization of materials, parts, tools, technical documentation, support personnel (internal and external), and transportation required to execute maintenance work.

In the high-technology processes of today, good maintenance technicians are a precious resource. They are the primary source of effort aimed at preserving reliable productive capacity from industrial equipment and processes. In most facilities, only technicians are contractually authorized to use tools. Yet, numerous studies show that maintenance technicians spend, on average, only two or three hours per day actually applying the tools of their trades. It is imperative, therefore, that traditionally staff-performed activities that consume a technicians time and are not related to equipment reliability or production goals be accomplished by alternative means and alternative parties (support staff). The aim of effective maintenance planning and scheduling is to optimize the utilization of maintenance resources, contributing directly to equipment reliability. Even when organizations are structured for increased worker involvement and stewardship of their equipment, someone must still be responsible for maintenance planning. The structured planning provided by para-professionals in a staff role within the maintenance structure remains an essential requirement, especially in those organizations that have adopted self-directed/participative team concepts. Some person or group must provide planning support in a methodical manner. Without planning, the resources used in the manufacturing process or in providing maintenance services are being consumed ineffectively. Unfortunately, many managers are slow to acknowledge the need. We return to the original question of just who is the appropriate person to assign to the planner function. The options are as follows.

2.1.3 The Assigned Tradesperson

If planning is left up to the employee, it is rarely performed well. It results in delay, wasted effort, and inefficiency. The worker engages in activities that reduce time available for direct work. Indirect activity and travel tend to be very high in proportion to direct work time. Because of his or her position in the organizational hierarchy, the tradesperson is not well postured for many of the liaisons associated with the planning and scheduling role.

2.1.4 The Responsible Supervisor (or Team Leader)?

Supervisory activity should be focused on instructions and control of methods, pace, and quality of work. First-line supervisors are organizationally postured to concentrate on immediate problems and have little time to focus on future activities. Given the demands of daily maintenance execution, it is difficult for supervisors to provide both the necessary supervision and coordination of today's jobs as well as the effective preparation of future jobs (tomorrow's and next week's work). One or the other is neglected. Given the choice and faced with the daily demands encountered, first-line supervisors concentrate on today's problems. Therefore, it is planning for tomorrow's activities that suffer.

Any time that a supervisor does spend on planning reduces the time devoted to field supervision, thereby defaulting on the prime supervisory responsibility of field supervision; in effect delegating the supervisor's own responsibility to the crew and losing the benefits, which his or her presence and availability bring to job execution.

Supervisors typically plan just prior to job start, thus leaving little time to consider methods, and identify and acquire required materials, tools, support trades, etc. The result is missing materials, delays, incomplete jobs, inefficient methods, questions and over staffing.

Nevertheless, because of a lack of maintenance understanding and reluctance to increase overhead, first line maintenance supervisors are, in many cases, expected to assume responsibility for job preparation as well as job execution. However, the assumed overhead savings are consumed many times over by resultant losses in job quality, equipment breakdown, and crew productivity.

When planning is handled by a supportive staff function, the first-line supervisor has more time for leading and directing his or her team:

1. More supervisory follow through promotes better quality or work and reduces unnecessary delay and idleness.

2. More time can be devoted to individualized training and instructing of team members, thereby, developing apprentices and lower skilled personnel into "tradespersons" of the highest capability, capable of maintaining today's high technology.

3. More time can be devoted to the practice of good employee relations with reduction of grievances and minimal organizational damage through prompt handling of those grievances that do occur. The resultant is high morale and work spirit of the team further contributes to increased team output.

The answer to the original question of just who is the appropriate person to assign to the planner function is: A Well-Trained Planner/Scheduler

Separate the functions of planning and supervision. Planning and execution require different skills. A combination of these skills in one person is the exception rather than the rule. Therefore, planning should be a paraprofessional, staff function, separate from work execution, although prior experience in work execution is an essential requirement. There are definite advantages that result from this separation.

2.1.5 Fostering a Sense of Accomplishment

In planning for others, it becomes most important to clarify objectives.

Plans need to be designed which provide satisfactory signals when those objectives are being reached. Means for providing feedback of success or failure must be built into plans for others. Performance of individual members working as a group improves the most when they receive constructive information about their individual efforts as well as the group's success as a whole, particularly if the problems are difficult. Equally useful is personal feedback of one member or another in improving the problem-solving efficiency of all.

Promoting Confirmatory Behavior: The confidence of planners in the adequacy of their plans can be communicated, while reservations of the doer need to be brought into the open and discussed with the planners. If the doers believe that the plans are unrealistic, even is the plans are actually sound, the doers may behave in a way to confirm their own beliefs. Planners need to share with the doers the reasons for their optimistic expectations.

Promoting Commitment: Doers can be consulted at various stages in the planning process. Wherever possible, the ideas of the doers can be incorporated in the plans, or when such ideas of the doers can be incorporated in the plans, or when such ideas are unusable, the reasons can be discussed with doers. The plans can provide for some discretion on the part of the doers to modify noncritical elements of the plans, thus increasing the feeling that the doers have some control over the fate of the plans, and consequently, responsibility for the successful execution of them. Built into the planning process can be provisions for periodic feedback of evaluation from the doers.

Providing Flexibility: While those who plan for themselves display more initiative in making needed changes in a plan, specific provisions to encourage such initiative are required when planning for others. It can take the form of an instruction asking doers to regularly report back to the planners whether the plan is working satisfactorily and where it may need modification. Planners may need to allow for a completely unforeseen contingency, the critical event whose occurrence could not have been anticipated, expected by the general instruction to the doers to modify the plan in a suitable way, if such and unsuspected event should occur.

Promoting Understanding: Understanding of the plan can be fostered by ensuring that the plan itself has been created in a way to minimize its ambiguities. Repeating instructions may increase reliability and understanding.

Crosschecks and tests of the plan's clarity before it is presented to the doers may be helpful also to ensure that the plan's instructions are simple enough to be understood by the least capable doer. If he or she can understand the stages of the plan, all others can also understand it.

Maximizing Effective Use of Available Labor Resources: This is a matter of making the most of what is available by whatever means the situation allows. Latitude should be commensurate with capacity. Planners need to incorporate allowances for individual differences in their plans for others.

Improving Communications: The doers must have (and feel that they have)

ample opportunity to question the planners for clarification of the presentation of the plans. The planners need to attend to whether or not they are overestimating or underestimating the ability of those who are receiving the plans to comprehend them. The planners need to judge whether they are transmitting too much or too little too fast or too slowly, with too much or too little enthusiasm, with too much or too little confidence.

Minimizing Competition: The planners need to avoid creating a situation in which the doers see themselves in a zero-sum game with planners. If the plans succeed, the doers must not lose status, prestige, power, or material benefits. Conditions must be established in which the doers share with the planners the same super ordinate goals. The division of labor should be seen as benefiting the doers as well as the planners.

Planning performed by a separate staff group has the added advantage of an overall functional perspective. Priorities, labor resource loading, and management reports are better coordinated through a controlled planning function. Several jobs can be planned more efficiently by a focused function than by an assigned tradesperson planning one job at a time. Therefore, the answer is that they all have a role to play Tradespersons, Supervisors and Planners, all contribute to the planning process.

Regardless of the organization used there should always be a current and complete organizational chart that clearly defines all maintenance department reporting and control relationships, and any defined/designated relationships to other departments. The lines of communications between staff and line functions as well as between departments, although less formal, should always be open. The Maintenance Organization should clearly show responsibility for the three basic maintenance responses: routine, emergency and backlog relief. The role of planning and scheduling is critical for the effective utilization of the maintenance line-resources.

PREV. | NEXT | Article Index | HOME