AMAZON multi-meters discounts AMAZON oscilloscope discounts

As stated earlier, whenever maintenance is performed, regardless of organization style, it is planned. However, the primary questions remain" who is doing the planning, when are they doing it, to what degree, and how well? Because planning and scheduling functions are at the hub of all maintenance activity coordination; these functions rate a professional grade classification and assignment of only professionally trained, experienced and qualified personnel.

--Maintenance Planning is the advance preparation of selected jobs so that they can be executed in an efficient and effective manner when the job is performed at some future date.

--Maintenance Planning is a process of detailed analysis to first determine and then to describe the work to be performed, by task sequence and methodology.

--Maintenance Planning provides for the identification of all required resources, including skills, crew size, labor-hours, spare parts and materials, special tools and equipment.

--Maintenance Planning includes developing an estimate of total cost and encompasses essential preparatory, post-maintenance and restart efforts of both operations and maintenance.

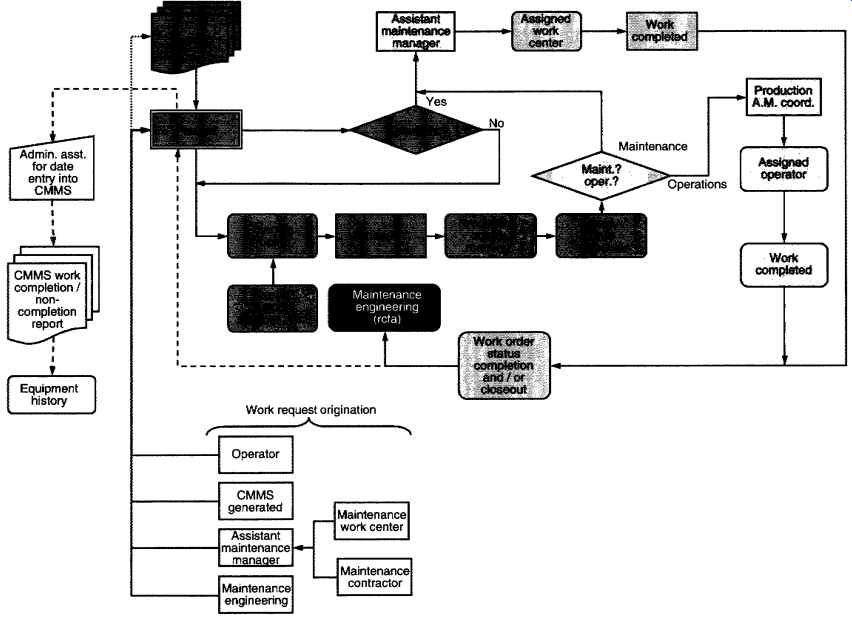

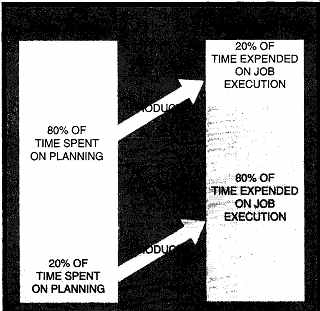

The Maintenance Planner must have the requisite personal skills as well as professional skills derived from experience and thorough, comprehensive training in order to execute "professional" Maintenance Planning. When these attributes are in place, the effective utilization of maintenance personnel can be increased by as much as 65% and job execution time can be reduced by as much as 40 to 50% (see FIG. 1).

FIG. 1 Professional Planning Saves Time (and Money!)

1. PRINCIPLES OF PLANNING

Perhaps more properly the listing that follows might be referred to as principles for the Planner to strive for in his or her day-to-day planning activities:

-- understand the department's mission in relation to the objectives of the company;

-- always be aware of the magnitude and trend of backlog;

--quantify the magnitude of the resources effectively available to apply toward relief of the backlog;

--establish a plan for the allocation of available resources to a balanced workweek, considering both long-range importance and short-range necessity;

--categorize work consistent with planned resource allocation categories;

-- assign a planning priority (within job priority and category) to each job;

--break each job into logically sequenced tasks/activities;

--prepare a "Planning Week" schedule by phases of work planning and by task to determine progress toward completion of each week's work planning;

-- work to meet this schedule.

Protect it. Do not superimpose new work unless that new work represents an overriding course of action for work planning (long and short range);

--measure progress and contribution. Don't spin your wheels on efforts that don't move toward completing the week's work planning.

1.1 Managing the Backlog

Maintenance is managed by managing the backlog. It is impossible for a facility to be proactive if resources are not kept in balance with the workload. If the overwhelming majority of jobs are not planned, there is no effective way to know what the magnitude of the backlog is and therefore it cannot be managed. Backlog is also an indicator of resource augmentation--through overtime, staff expansion or outsourcing. Backlog Management begins with the Maintenance Planner and culminates with the Maintenance Scheduler.

Just what is backlog? In the simplest of terms, backlog is work that has not yet been completed. When a work order is generated, it contains, among other information, a priority code. The work order, or job, priority determines when the work will be planned, scheduled and performed relative to other jobs. When the planner has completed all of the planning functions for a work order, the job is ready to schedule or available. If the work planning is not completed, the work order is not ready to be scheduled or unavailable.

Together these two classifications of work order status constitute the backlog. Backlog is measured in time, normally hours that are translated into labor weeks. The hours of backlog are the resource, or labor hours that the work is estimated to take. The normal range for backlog, based on 80 to 90% of jobs being planned, is considered to be:

Ready available backlog is equal to 2-4 weeks of labor hours Total backlog (available and unavailable) is equal to 4-6 weeks of labor hours The reason that the norm is defined as being based on 80 to 90% of jobs being planned is because, for unplanned jobs, the estimated labor hours are not yet known. For example, 10% of the backlog (number of work orders) is unplanned and the planned portion (90% of the work orders) of the backlog is 1800 hours. The assumption is made that the unplanned portion consists of work similar in labor hour requirements to the 90% of the work that is planned, in this case, unplanned is equal to 200 hours, for a total backlog of 2000 hours. The calculation is: 1800 hours divided by 90% equals 2000 hours (100% or Total Backlog), and 2000 minus 1800 equals 200 hours (total minus planned equals unplanned).

Obviously, if the planned work is very much below 80% of the total, confidence in the estimation of the unplanned work becomes lower and as a result, control of the backlog is lost because the size of the backlog is unknown.

When equating the hours of backlog to weeks of backlog, straight time and scheduled overtime are considered. For example if the average maintenance work force available during any given week is five tradespersons with 2 hours per person scheduled for O/T, then one week of backlog is equivalent to five times 40 (hours) or 200 hours plus 10 hours O/T = 210 hours/week available capacity. Backlog is referred to in weeks simply because it is more understandable than four or five figure hourly references.

The Maintenance Planner must prepare a weekly Backlog Status Report.

The report can contain as much or as little information as desired, but as a minimum must include the following:

--total backlog (total labor hours of all open work orders in the CMMS);

--ready backlog (total labor hours of work orders ready to schedule);

--age of backlog;

< 1 month

1-2 months

3-6 months

> 6 months

-- trend charts

total labor hours completed versus # of backlog work orders completed

total available labor hours

total scheduled overtime hours

CMMS can be used to automatically generate and disseminate the (planner reviewed and approved) Weekly Backlog Status Report. The Planner should provide a copy of the report to all attendees at the Weekly Maintenance Schedule Planning Meeting prior to the day of the meeting.

In addition to being available or unavailable, backlog also has the characteristic of age. Age simply refers to how old the work order is. The primary determinant of ageing is the work order priority. Obviously the higher priority work orders will be planned before the lower priority ones, therefore one would expect the "youngest" work orders in the available backlog to be predominantly made up of high-priority work orders. As a management tool, work order age is important in decision making regarding the cancellation or re-prioritization (to a higher priority) of older work orders in the backlog.

Section D, Section D 1, provides a short tutorial on the use of control charts as an aid to backlog management. Exhibit C-8 of Section C also contains a Backlog Worksheet that can be utilized in backlog management.

In order to manage and control backlog to predetermined levels, i.e., 2 to 4 weeks of ready available backlog, the Maintenance Planner and the Maintenance Scheduler (if planning and scheduling are assigned to separate people) must work together closely. They must know the level of resources (personnel) available each week. If there is a decrease in available resources (vacation, training, etc.?) there will be corresponding increase in backlog.

Without prior knowledge of resource levels, the backlog could go out of the control band. Backlog trends up or down should be investigated if the cause is not known in advance. It is important to know whether it is a temporary trend or a permanent one (e.g., a continuing trend of decreasing backlog is very likely an indication that the size of the maintenance group is too large for the maintenance workload). For the planner and the scheduler to manage backlog based on available resources, they must be apprised of resource levels on a weekly basis. Each maintenance supervisor must be required to submit weekly manning level reports to the maintenance scheduler in order for the scheduler to know how much of the planner's available work can be scheduled. Section C, Exhibit C-2 illustrates a "Weekly Resource Report" reporting form that provides all of the information necessary for this weekly reporting requirement.

====================

Table 1 Equipment Criticality (Fixed)

Criticality 10

Description

Shuts down entire plant---e.g., utilities Shuts down more than one linemkey production equipment Not spared production equipment/shuts down one line Mobile equipment--e.g., fork truck, transporters Spared production equipment/not spared support equipment--product can be made on one or more lines Support equipment spared Infrequently used production equipment Miscellaneous equipment--e.g., water cooler, windows, cafeteria Roads and grounds Buildings and offices

=====================

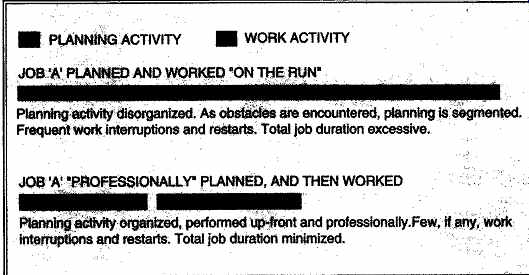

1.2 Criticality and Prioritization

The Maintenance Planner initiates job planning based on work orders received and the coded information on the work order. The coded information includes work type, work category, work classification and perhaps others, but initially the primary interest of the planner is focused on the priority that has been indicated for the work (priority: something given or meriting attention before competing alternatives). 3 Job priority is the determinant for sequencing work planning: the highest priority jobs are the first to be planned and the first to be scheduled. Job priority is assigned by the originator of the work order (request). The priority is based on equipment criticality and on the type of work to be performed.

The first of these, Equipment Criticality, ranks each piece of equipment in relation to its impact on the production process. Assignment of equipment criticality should be made jointly by Operations (Production) and Reliability Engineering. If equipment criticalities have not been assigned, it is the responsibility of the Maintenance Planner to ensure that they get assigned, a responsibility where the planner's tact, perseverance and persuasiveness can be put to the test. The generation of an equipment listing with "tentative" criticality codes (see Table 1) assigned by the Maintenance Planner might expedite the process.

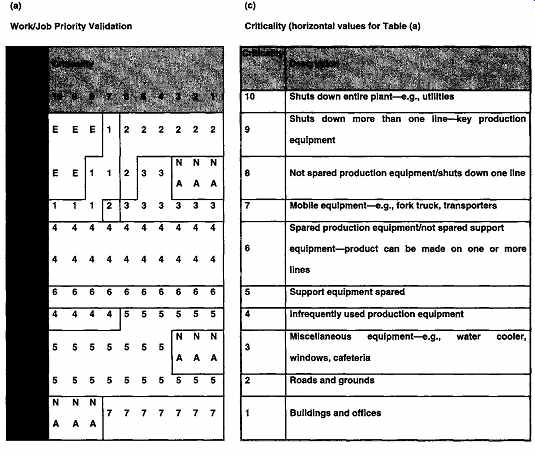

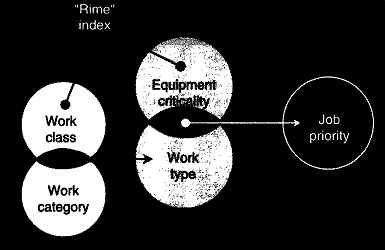

The second, Work Type, is determined by (1) work class and (2) work category. Work class is a dynamic attribute such as breakdown repair or repair of a potential failure (failure is imminent; e.g., an overheating bearing) while work category is a fixed attribute such as preventive maintenance or equipment alteration. The work category is also defined, in part, by the purpose of the work such as correction of a safety problem or improvement of equipment efficiency (economics). A ranking index for maintenance expenditures (RIME) has been developed to help maintenance departments do a more equitable and logical job of controlling maintenance expenditures. The RIME index consists of: (a) equipment criticality, relating to equipment capacity and reliability, estimated repair costs and impact on the process, and (b) work class, which takes into consideration safety hazards, operating costs, and labor.

Combining these two RIME elements provides a better determination of which maintenance jobs should be scheduled for completion first. A comparison of job RIME numbers will indicate which jobs are essential and which ones can wait. Application of the RIME index results in better maintenance decisions and leads to better planning. The equipment criticality codes are the same as previously defined in Table 1. The work class descriptions are provided in Table 2. Work Class ranks each job in relation to each maintenance job or project. Following Table 2 is a series of tables in Table 3 (a through d) with "suggested" priority assignments for the RIME matrix. It is emphasized that these are suggested priorities. The relationship between equipment criticality and work class as they relate to work order priority assignment is a local policy issue for individual plants.

Whatever the priority correlation with the RIME Index, it should be spelled out in the plant's Work Management Standard Operating Procedure (SOP). In addition to this "local policy" characteristic, the RIME Index assigned priorities must also have built-in flexibility sufficient to allow any values to be overridden by the Plant Manager, the Maintenance Manager and/or the Production Manager (Table 2).

=============

Table 2 Work Class (Dynamic)

Index

10

Description

Breakdown/Real Safety/Regulatory Compliance/Quality Product/quality loss Potential breakdown Preventive maintenance Working Conditions/Safety/Security Shutdown work Normal maintenance Projects and experimental Cost reduction Spare equipment/parts

==============

Table 3 RIME Index Priority Assignments

==============

Index #

10

Work Class Definitions

Breakdown--Real Safety Regulatory Compliance: Equipment stoppage during plant operation. No production output.

Immediate threat to life or limb. Environmental impact or a serious citation that may shut down a piece of equipment (e.g., high-voltage panel not protected).

9

Product--Quality Loss: A malfunction that does not result in line shutdown but causes intolerable product/quality problems (e.g., code date, open flaps).

8-1

Potential Breakdown: an identified problem which must be corrected as soon as production is curtailed (e.g., conveyor belt splice is tearing apart). Preventive Maintenance: Repairs that are identified and performed in a preplanned mode to avoid breakdown and all normal work orders generated from performing PM work orders and inspections (e.g., inspections and running adjustment). Shutdown Work: Work which is not critical enough to require immediate shutdown but must be performed only during a planned shutdown period (e.g., major overhaul jobs that are large in scope). Normal Maintenance: Routine work that can be planned, scheduled and completed without disrupting planned production output (e.g., rebuild gear case). Working Conditions--Safety and Security: Any change in physical environment that is either aesthetically pleasing or motivational, minor safety and security work (e.g., repaint, repair and office door/lock). Projects and Experimental: Engineering projects which are requested to modify design, or improve reliability of equipment or processes (e.g., installation of hot air sealer). Cost Reduction-Corrective Maintenance: Work that results in operational changes that will reduce unit costs and does not fall into one of the higher classifications. Replacement of a defective component to eliminate or reduce repetitive repairs (e.g., metalizing a cylinder rod, replacing an open bearing with a sealed bearing).

Spare Equipment-Parts: Fabrication of multiple spare repair parts (e.g., turning multiple spare pump shafts in a lathe).

The RIME index can also be useful to the maintenance planner as an evaluation tool in determining the validity of originator assigned job priorities, although, most often, the job priority is self-evident and does not require validation by the planner. However, if there is a question regarding job priority assignment, the planner must always direct any questions back to the work order approving authority for resolution.

This may all seem quite convoluted: work type, work class, work category, work purpose and seemingly on and on. The graphic in FIG. 2 may help to make the relationships and usage of work/job attributes a little clearer.

FIG. 2 Relationship of Priority to Work and Equipment Classifications

Job Priorities are assigned by the WO approval authority. Priorities rank each job in relation to others and establish a time frame within which jobs should progress. Priority code systems can range from 3 or 4 rankings to as many as 15; too few rankings do not provide adequate separation to aid in decision-making, while too many can become cumbersome and difficult to manage. The objectives of assigning work priorities are to:

--separate plannable from un-plannable work;

--facilitate sequencing of work order planning and execution;

--provide indication of lead time available to plan.

Table 4 illustrates a recommended Priority Coding system. Following Table 4 are complete condition descriptions of each indexed priority code:

"E" Emergency: Must be performed immediately. Higher priority than scheduled work, critical machinery down or in danger of going down until requested work complete. "E" to be used only if production loss, delivery performance, personnel safety (new and imminent), equipment damage or material loss are involved and no bypass is available Start immediately and work expeditiously and continuously to completion, including the use of overtime without specific further approval. Only personnel authorized to approve overtime can assign "E" priority to work orders. Emergency work order reports will be sent to plant manager for review.

Needed within a few hours, by end of shift at latest. It is the opinion of the work order approval authority that the work must be completed as soon as possible but does not constitute an emergency requiring immediate attention. Maintenance personnel are assigned as soon as available without halting a job already in progress.

Overtime approval is not implied by "1" priority.

Overtime authorization must be obtained by special request, given specific circumstances, from the authorizer or designated authority. Priority "1" should be used for equipment that is down or in danger of going down and which affects ability to produce desired product mix or renders plant void of backup capacity in event of subsequent failure.

Needed within 24 hours. Similar to urgent (1) jobs but with less urgency. Typically good work to leave for off-shift coverage personnel. Controlled use of "E," "1" and "2." Priorities must be reserved for truly critical situations or they diminish planning and scheduling effectiveness.

Must be performed before end of current week.

Normally, this work will be scheduled to start within 48 hours after receipt of the work order. Priority 3 jobs (as well as "E," "1" and "2" jobs) cannot be effectively planned before scheduling. All jobs should be assigned priority "4" or higher whenever possible.

Priority 3 jobs will be used as fill-in work for personnel responding to emergency and urgent work orders or will be forced into the current week's schedule, "bumping" a properly planned job already on the schedule. Performance on the job will be measurably less efficient and cost will be measurably greater than if planned (Priority "4" or "5"). Must be performed before the end of next week. This work can be effectively planned. It will be scheduled next week (as opposed to being scheduled in the order of request date). Realize that all requests cannot be completed next week. Priority "4" requests delay the completion of previously requested work of lower priority and drive up the cost of requested work, as overtime will be requested to meet the time/demand constraints implied by priority. Use Priority "5" if possible.

Designates desirable but deferrable jobs. Can be completed anytime within the next few weeks, and can therefore be scheduled on the basis of first requested--first scheduled. A desired completion date may be indicated by the originator. Weeks of backlog report provide the current wait to be anticipated on Priority "5" jobs. Overtime will not be used on Priority "5" jobs unless the work must be performed on a non-operating day or aging of the request exceeds six weeks.

Work requiring programmed shutdown. Work orders in this category are accumulated for shutdown planning.

Used exclusively for routine work. Usually assigned to standing work orders, "7" is not associated with normal day-to-day work order requests.

1 Urgent

2 Critical

3 Rush

4 Essential but deferrable

5 Desirable

6 Shutdown

7 Routine

===============

Table 4 Job Priority Assignments

===============

Assuming that priority codes E, 1 and 2 (Emergency, Urgent and Critical) are well controlled and used only for truly critical situations, the planner is predominantly involved with work orders of priorities 3, 4 and 5. Priority 6 (shutdown work orders) is discussed later on in Section 8 and priority 7 (routine work orders) is dealt with differently in the Lean Maintenance Environment and will be discussed later in this section. Within priorities 3, 4 and 5 are requested completion times of 3 to 4 days, 5 days to 2 weeks and 2 weeks to 5 or 6 weeks. It is this latter category that comprises the majority of backlog work. The age of priority 5 work backlog is the primary determinant for scheduling sequence. Work Type and Equipment Criticality are secondary scheduling determinants for work orders of the same age.

----------

Special Note on Safety Jobs:

Safety jobs are highlighted on the work order by reason code "S." Safety priority is always high. If there is an active hazard requiring immediate attention and correction, the work order should also be given an "E" Priority. All safety jobs not given an "E" priority should be handled on an individual basis and assigned one of the applicable priority codes above.

-------------

1.3 The Work Order

The heart of Maintenance Planning beats only as strong and healthy as the Maintenance Organization's Work Order System functions.

Knowledge and control of the tasks to be performed are essential to all functions. For maintenance, the source of such knowledge and control is the Work Order.

1.3.1 Work Order Types and Formats

There are three basic work order types or formats:

1. Formal Work Order

2. Standing Work Order (SWO)

a. Daily Checks/Routines (SWO subtype)

3. Unplanned/unscheduled (break-down) Work Order

The Formal Work Order is used for those jobs that enter the backlog and that can be planned each time they occur. In designing the formal work order, a decision is required: single-trade format or multitrade format.

--Single-trade format. The single-trade format is an internal maintenance department document (usually a copy of the child work order and attached to the parent work order) assigning portions of job to trade other than parent and aids in coordinating multitrade jobs. Jobs are planned and scheduled in the same manner and carry the same reference number as the parent work order.

--Multitrade format. A multitrade work order details work sequence by craft in the planning section of the work order. For control of activity, backlog and performance by craft, it is essential that the computer system treats each sequence line of multitrade work order as separate jobs.

Manual systems (as opposed to CMMS) often lose control by trade if a multitrade work order is utilized.

Standing Work Orders (SWOs) are used primarily for periodic jobs performed on a predetermined schedule, in a standard pattern and involving a standard amount of work. It is unnecessary to prepare unique work orders each time these jobs become due. SWOs are commonly established to absorb charges for the following types of work:

1. Routine inspection, lubrication, adjustment and service of equipment.

a. Includes most Autonomous Maintenance (Operator performed)

2. Repetitive service work:

a. Re-lamping

b. Trash removal

c. Janitorial duties

d. Material and supply transportation

e. Fire checks.

3. Bench work with visible backlog

4. Daily checks/routes

5. Minor, short- and low-cost repairs by a technician assigned to a specific unit where no equipment history is required.

6. Nonmaintenance activities:

a. Safety and union meetings

b. Training.

SWOs are assigned to individual cost centers, but should also permit separation of expenses by equipment number when issued for work exclusively on a particular machine. Any corrective work should be captured on a formal work order.

Repetitive service work is most economically controlled without the use of a formal WO. For each task in a day's work of this type, the effort and expense involved in formal WO are not justifiable. The cost of execution is not much more than expense of preparing, coordinating and controlling formal WO. SWOs should be numbered separately from the WO sequential numbering scheme and the date performed code appended to control and track their cost and performance. By identifying work of this nature and controlling it with standing work orders, a large quantity of minor tasks can be controlled promptly, effectively and economically. However, only a minimum number of the most useful and necessary standing work orders should be established.

Most, if not all, Preventive Maintenance tasks are automatically generated by CMMS. Preventive Maintenance tasks are pre-planned, thus limiting the planner's involvement. However, any corrections or modifications required for pre-planned Preventive Maintenance tasks should be reported to the Maintenance Planner, who is then responsible for developing any changes required. The Maintenance Scheduler lists those CMMS generated PMs on the Maintenance Weekly Schedule in order to coordinate equipment availability, track performance, schedule compliance and generate equipment history. The Preventive Maintenance Group Supervisor is responsible for ensuring completion of all Preventive Maintenance on schedule. Additionally, the supervisor determines which routine PMs are to be performed by the Production Department Autonomous Maintenance Teams. Through coordination with the maintenance trades assigned to these teams, the PM Group Supervisor assigns them minor and routine PM tasks based on the level of training and demonstrated skills of autonomous maintenance equipment operators. The PM Group Supervisor may assign nonminor and nonroutine tasks to the Autonomous Teams when and if their training levels support such work and the team's resource levels are sufficient to perform the additional maintenance.

SWOs should be reviewed, validated and redefined monthly, or at some other predetermined frequency. Estimated costs are identified and authorized for each by designated authority. Charges are controlled against monthly budgets. Cost variance reports for each standing work order should be closely reviewed. Sharp fluctuations or excess charges should be investigated to determine cause and initiate corrective action. Daily checks/routes that simply employs a one- or two-line entry into a chronological log represents another variation of the SWO. Typically, these are once per shift or once per day readings taken from equipment instrumentation and similar high-frequency, low-effort work. Each sheet (template) is assigned a unique number and the date or period (normally one week) covered by the check/route entries is entered when the sheet is completed. Data from completed sheets should be entered into CMMS equipment history by the Planning and Scheduling group's administrative clerk/aide. Costs are handled in the same manner as SWOs.

Unplanned/unscheduled work orders are used for those jobs that must be completed within the next day or so, without the opportunity to plan completely or plan at all, as they require immediate attention. These work orders will have a high-priority rating. Completion and closeout of this type of work order requires documentation of all actions taken. Labor and material costs are logged back to the equipment and a copy of the details of the failure and repair are forwarded to Reliability Engineering for further failure analysis.

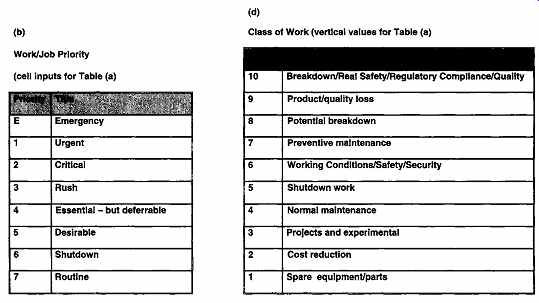

1.3.2 Work Order System and Work Flow

The work order should be viewed as a system, not as a form or procedure.

The work order provides the means for requesting maintenance service, and thereafter planning, scheduling, controlling, executing and reporting the work performed.

An effective WO System:

--screens out the unnecessary and unimportant;

--establishes responsibility;

--reduces mistakes;

--provides an understanding of what is to be done;

--provides a means of charging labor, material and outside services to the equipment owner;

--serves as an authorization document;

--is a source document for maintenance cost and performance control;

--is the drive wheel of integrated maintenance management.

Through proper use of the WO system, accurate work backlogs are established, job preparation is facilitated, control of maintenance work is enhanced, equipment histories are created and optimum effectiveness of maintenance work groups can be achieved. There are two approaches to administering a WO system. The first is characterized by the use of work requests, which are submitted to the maintenance planner who is then responsible for generating, including the coding of all data fields, the work order. The second, which is used in capturing unplanned/unscheduled work, is characterized by initiation of the work order directly by the originator. The completed work order is then submitted to the planner for additional coding and CMMS entry.

While the work order is used in conjunction with other functions, such as time keeping, inventory control and purchase orders, as input to the accounting cost allocation system, the work order is first and foremost a maintenance management tool. Before development of CMMS, maintenance costs were charged directly to cost control accounts (in varying degrees of specificity)

via the other three functions listed above. Nonmaintenance costs are still widely accumulated in this manner. Combined usage of the work order system for cost control as well as operational control came about as an enhancement to tie the two systems together and to avoid duplicity of input effort.

Many installations still do not merge the two systems.

Work Order Control System

The work order is a control document serving three basic functions:

1. Definition and authorization of work to be performed.

a. Systematic screening and authorization of work requested in respect to work type, location, urgency and cause.

2. Planning and control of work to be performed.

a. Record and measure amount of work coming in (inputs)

b. Assign priorities

c. Provide information needed to plan, schedule and coordinate methods, materials, labor

d. Supply supervisors and technicians with job instructions and estimates of the time required

e. Accumulate information on job progress

f. Record and measure amount of work completed (outputs)

g. Control manning levels to balance output with input

3. Maintenance History accumulation and input.

a. Develop time estimates for repetitive work

b. Perform Maintenance Optimization and Root Cause Failure Analysis (RCFA)

c. Cost and performance measurement and improvement

d. Analyze costs by job, equipment and cost center

e. Improve planning, scheduling and preventive maintenance

Maintenance Work Order Data

The matrix of data in FIG. 5B, showing all work order fields, responsibilities and terms for data entry, apply to plannable, comprehensive work orders. Some simplification is provided for standing and unplanned/ unscheduled work orders.

The workflow of the work order should be consistent and should not be bypassed for minimal speed gains or convenience. Even unplanned/ unscheduled work originated by emergency or urgent priority work order should pass through the maintenance planner when completed. Delivery of high-priority work orders can be made by hand and in person to expedite handling, but to ensure proper logging, handling and follow-up, all work order priorities must go through the planner. In addition, it is just possible that the repair called out in an emergency work order has been performed before and archived plans may be available. In the long run, consistent handling may actually speed up the repair process--even of high priority, normally unplanned, work. FIG. 3 illustrates an effective workflow scheme.

Table 5A Minimum Work Order Information

Table 5B Minimum Work Order Data

1.3.3 Coding Work Order Information

It is clear from Tables 6-5A and B that, unless some sort of shorthand for entering the required information on the work order, the work order form will need to have 8 to 10 pages. Fortunately, there are (relatively) universal codes, numerical, alphabetical and standardized phraseology and acronyms, that are used to annotate work orders. Whether you use the coding provided here, or formulate your own, work order codes and definitions must be widely published and must be used by everyone that will encounter the work order. The mandatory and universal use of standardized coding (and abbreviations or acronyms) throughout the plant cannot be overemphasized. Even if only one participant deviates from standardized practices, the work order control system is compromised and history will be inaccurate.

Following then are some suggested work order coding schemes.

Work Order Status Codes

Status codes are for the tracking of work orders as they progress through the life of the process. Only work orders that have reached the status of ready to be scheduled or "available" are considered for scheduling and execution. Both numeric and alphabetic codes together with their description and person responsible for code assignment are provided in Table 6.

Table 6 Work Order Status Codes and Descriptions

Definitions of Work Order Status Codes

Code Description: Definition

01/P

02/E

03/A

04/PF

05/PO

06/M

07/FP

08-1 I/D

08/DW

09/DP

10/DS

11/DO

12/R

13/FI

14/S

15&16

15/CM 16/CP

17/C

Waiting to be Planned: This code is recorded as a work request is received. Even though no estimates have been posted, it is imperative that all requests be captured and added to the backlog immediately. The goal is to keep the WO system as near to "real time" as possible. In some cases, a backlog builds in front of the planners. This code provides awareness of that condition.

Without it, awareness is sacrificed. Whoever enters the work request into the computer system is responsible for entering the initial status code or it can be set as the default code. All but the emergency and urgent work requests pass through this status.

These two priorities do not pass through the planner unless their priority is downgraded. They never reside in backlog, so their status need not be tracked. They are either open or completed.

Awaiting Engineering/Design: Upon review of a work request, planners may determine that engineering and/or design is required before that job can be planned. Until the required design documents are returned by engineering, the request resides in status code -02.

Awaiting Management Approval: More costly jobs require higher authorization levels for approval. Planners or engineers develop the necessary costs estimates and forward the necessary documentation to the appropriate individual(s) for approval. With approval by the required authorization level, the work request becomes a work order.

Awaiting Funding: Cost estimates may be more than the current budget allows. Until funding is determined, the work order resides in this status.

Awaiting Purchase Order Issuance: This code is a sub-status of awaiting material. At times, the internal processing time consumes as much lead-time as external processing and delivery time. Status code-05 captures this condition. Management focus may be directed to the capacity of purchasing/buying resources. If processing time is under control, the status code is optional-a local judgment.

Awaiting Material Receipt: From the time the necessary purchase order is issued until receipt of the associated material on the local receiving dock, the work order resides in this status. The responsible buyer enters this code upon the purchase order issuance. If "06" is not employed within the system, the planner enters this code upon issuing a PO request.

Awaiting Further Planning: Once materials have been received, there may still be some planning to be completed. Depending on the local network, either a receiving clerk or a planner should enter this code upon material receipt.

Awaiting Required Downtime: This is a series of status codes indicating the type of downtime required to complete the work order. Downtime backlog must be separated from that which can be performed at any time (even if equipment is operating). Awaiting Weekend Downtime" Most processes have at least some equipment down each weekend.

Awaiting Programmed Downtime: Many processes have elongated schedules (month, quarter, and year) for the operation of each line, with predetermined opportunities to relieve downtime backlog.

Awaiting "No Production Scheduled": In addition to the programmed shutdowns, equipment becomes available as a result of week-to-week production scheduling. Planners need to make themselves aware of these additional opportunities to relieve downtime backlog.

Awaiting Downtime Window: This code is for the short duration jobs requiring only an hour or two of downtime. They can often be completed during unscheduled downtime that occurs for other reasons. If planners will take a moment of additional effort to categorize downtime work orders into these four groupings, the computer can then be used to retrieve expeditiously backlog applicable to each opportunity presented.

Ready to be Scheduled: Planners are responsible for getting work orders to this status as rapidly as possible. There are no encumbrances. If labor is available, the job can be scheduled.

Ready for Fill-in Assignment: These work orders are also ready to be scheduled. However, they are ideal fill-in jobs for mechanics with some form of fixed assignment. They can be readily started, dropped and resumed between more pressing demands of their fixed assignments.

Scheduled: This code is used to identify jobs still open but which are on the schedule (forecast or plan depending on local terminology) for the current or following week.

Contingently Completed: Two codes are used for special control purposes. All maintenance work is complete and the jobs no longer show as crew backlog.

Completed with Materials or Rebuilding Pending: In some situations it may be desirable to charge some replacement parts not yet received to the otherwise completed work order. Possibly the removed assembly must be sent outside for rebuilding and the system calls for capturing the rebuild charges to the same work order as the "remove and replace" efforts.

Completed, Pending Print Revisions: "As installed" prints must not be allowed to become outdated. This can easily happen, and all too often does. Even if maintenance properly marks (red lines)

their working copies and forwards them to engineering for revision, an indefinite backlog frequently occurs. This backlog of print revisions can have serious adverse affect on maintenance effectiveness. It must be controlled. Status code-15 provides the necessary management awareness.

Closed: Moved or ready to be moved in to equipment history.

Table 7 Trade/Skill/Unit Codes

Table 8 Work Order Classification (Type) & Purpose Codes

Accumulating Maintenance History

The last function of the WO control system is documenting the work that was actually performed during work execution. Labor and materials are charged to the work order through the time entry and stores systems. Work performed, components affected, condition of components and cause of failure are key elements for the accumulation of equipment maintenance history from the work order. Additionally, they provide valuable information for conducting failure analysis. Reasons for Outage/Failure Code (Equipment Failure by Probable Cause) are provided in Table 9.

Table 9 Equipment Failure by Probable Cause Codes

Table 10 Action Taken Entries (Verb of Description)

Table 11 Condition Codes (Adjective of Description)

Table 12 Component (Noun of Description)

As a final note, in particularly large plants, it is advisable to develop a coding system for locations where the work is to be performed. The coding system may require as many as three or four segments to the location field.

When a plant site has multiple production buildings, each building should be numbered or abbreviated. General location within structures can be coded by geographic reference or production zones or both. For example, the location for work to be performed in the Final Assembly Building, on the rolling stock (large) assembly line # 2 in the northwest corner of the building might be coded as FAB.NW.RSL2.

1.4 Sequence of Planning

The planning and scheduling function is the center from which all maintenance activity is coordinated. While planning and scheduling are closely related, they are distinct functions:

--Planning (how to do the job): Planning is advanced preparation of selected jobs so they can be executed in an efficient and effective manner during job execution that takes place at a future date. It is a process of detailed analysis to determine and describe the work to be performed, task sequence and methodology, plus identification of required resources, including skills, crew size, labor-hours, spare parts and materials, special tools and equipment. It also includes an estimate of total cost and encompasses essential preparatory and restart efforts of operations as well as maintenance.

--Scheduling (when to do the job): Scheduling is the process by which required resources are allocated to specific jobs at a time the internal customer can make the associated equipment or job site accessible.

Accordingly, the preferred reference is "Scheduling and Coordination." It is the marketing arm of a successful maintenance management installation.

Considered together, these two elements represent "Work Preparation." Their importance and absolute essentialness are predicated on the principle "Maintenance management will achieve best results when each worker is given a definite task to be performed in a definite time and in a definite manner." The supervisor, the worker and their colleagues should each know what is expected--including the goal and target time for completion of each job. The planning process begins with the following considerations:

--Control minor maintenance work activities within the plant work control system.

--Determine the level of detail necessary to accomplish maintenance tasks and troubleshooting.

--Use maintenance history in planning corrective maintenance and repetitive job tasks.

--Identify needed support to perform maintenance.

--Prepare and assemble a maintenance work package. Related follow-on to this includes:

o procedures and work package approval o work package closeout and maintenance history update.

A system of planning, scheduling, coordinating, executing and closing out maintenance work activities should be clearly defined based upon a plant Standard Operating Procedure (SOP), which should consist of five interrelated processes applicable to each maintenance job. These processes are:

1. Plan Maintenance Job. Identify the scope of a needed maintenance job. Produce a maintenance job plan. Determine maintenance job planning category, priority, and safety concerns. Identify and procure materials, and identify other maintenance task resources. Prepare the maintenance job package.

2. Schedule Maintenance Job. Calculate estimated start date and project resources for the maintenance job. Schedule and commit required resources and special tools/equipment items to allow performance of all maintenance tasks within the maintenance job.

3. Execute Maintenance Job. Initiate and perform a maintenance job and collect job information as defined in the maintenance job package.

4. Perform Post-maintenance Test. Verify facilities and equipment items fulfill their design functions when returned to service after execution of a maintenance job.

5. Complete Maintenance Job. Perform maintenance job closeout to include completion of all documentation contained in the maintenance job package to ensure historical information is captured.

1.4.1 Job Plan Level of Detail

Actually, before even considering the level of detail, the planner must determine or decide if this Work Order should be planned. Planning thoroughness increases as the installation matures. Any factors that might delay or hinder effective job completion should be anticipated and provided for in the "planning package." Planning completeness does vary with job repetitiveness. If the job is repetitive in nature, the planner can afford to invest more time since his or her efforts will yield repetitive returns in months and years to come. "Planning efforts will yield residuals." Conversely, if the job is clearly a one-time effort, planning should be taken only to the extent that the effort will result in a completed, reliable and timely executed maintenance action. Longer duration jobs will also benefit proportionally from more detailed planning. Additionally, it is often the case that components of even nonrepetitive planning packages can be reused if the job is effectively planned in "building blocks." These are prime reasons for providing sufficient planning capacity in early phases of program installation. When there is enough planning capacity to avoid the "hurry up" syndrome, the preferred approach is to prepare a very thorough planning package for any repetitive job encountered. In this manner, planner reference libraries are established more rapidly and planner workload diminishes as repetitive effort diminishes through the expansion and use of reference libraries.

The appropriate detail or degree of planning is often open to question.

Unnecessarily detailed planning on simple jobs can be more work and more expensive than can be justified. It is normally concluded that the smaller the job, the less planning required. However, the actual tendency is to under-plan normal-size jobs rather than to over-plan the simple ones. Even a small one-hour job that is mistakenly made available with some essential information or materials missing can cause considerable loss of time due to unnecessary travel and/or reassignment. Jobs of medium to small size are frequently neglected relative to planning detail.

The eventual answer to the original question of whether the work order should be planned is, "Plan all work orders whose performance can benefit from planning." At the same time, planning should not become an insult to a tradesperson's ability. It pays to have a good familiarity with the skill levels of the tradesperson whose work you are planning.

The question of planning detail applies primarily in early implementation phases of the planning and scheduling functions, when there simply is insufficient time to plan all jobs effectively. This situation diminishes as planner references are developed and reference files of preplanned work packages are built for repetitive jobs. Planners must avoid getting bogged down in unscheduled and emergency work, if any other maintenance planning is going to be completed. Following are derived definitions applicable to level of detail progression in job planning:

Simple

Every Job Plan/Work Order will have reasonable detail in its description and scope of work Safety Issues will be identified Labor estimates and downtime will be established Skills will be determined and assigned

Priorities have been established with the requester/customer Job Plan follow-up comments are solicited Communication with requester/customer prior to starting work and after work completed.

Average

Everything in a simple job plan will be expected as well as the following: Detailed JSA's, increased detail in the disassembly, assembly, installation, corrective repair steps

Specifications are included. Ex. Torque values, clearances, wear limits, etc.

Materials are allocated and received prior to work starting Special tools and equipment identified

Work area housekeeping and tool returns

More details in follow-up comments expected for improvement of process.

Advanced

Everything in a simple and average job plan will be expected as well as the following:

Engineering drawings included as the complexity of the job plan warrants

Schematics supplied as part of the job plan as necessary Testing requirements and Quality controls detailed

Special needs and hazards are identified within the job plan.

Not all job plans will require the complete details of the advanced However, all work orders should have the fundamental elements of the Job Plan Template.

In early phases of Planning and Scheduling implementation, a two-, four-, or even eight-hour cutoff point is often established for the magnitude of jobs that will be planned. As indicated, the selected cutoff point should be progressively reduced as the planning and scheduling function matures.

Generally, larger jobs are planned first on the theory that there is a greater likelihood of delay and conflicts and therefore a greater opportunity for positive impact by planning. Conversely, delays encountered in smaller jobs have a more dramatic percentage impact.

The Pareto Principle

The Pareto principle, often referred to as the 80/20 rule, states that the most significant items in a given group normally represent a relatively small portion of the total items in the group. The wisdom of focused and well thought out effort is apparent and indicates that effort to control the "vital few" can bring results out of proportion to the efforts expended. FIG. 4 graphically illustrates the Pareto Principle as it applies to the work planning function.

FIG. 4 Pareto Principle and Job Planning

PREV. | NEXT | Article Index | HOME