AMAZON multi-meters discounts AMAZON oscilloscope discounts

<< cont. from part 1

1.4.2 The Work/Job Package

Table 13 depicts the contents of a full or complex Planned Work Package. Not all of the nine elements are required for every work package.

The remainder of this section outlines the processes and considerations for development of the full work package.

There are conditions or practices that can enhance the work planning process. Among them are:

1. Complete equipment repair history

2. Thorough PM inspections

3. Timely reporting of potential problems by production

4. Thorough failure analysis by Reliability Engineering

5. Open dialogue with operators on troublesome equipment

6. Supervisor awareness of impending problems

7. A planned component replacement program

8. Existence of in-house overhaul and rebuild capabilities

9. High quality of work by trade personnel

10. Good use of repair technology

====================

Table 13

Contents of the Work Package

Work/Job Package

1 Work Order/Job Plan (includes resource requirements)

Technical Manual (if applicable--procedures, drawings, etc.) Pre-Test/Pre-Maintenance Checks (if applicable)

4 Bill of Materials Drawings/Sketches/Photographs Step-by-Step Procedures Time--By Step, By Allowance Re-Test Requirements/Procedures Post-Maintenance Notification and Reporting Requirements

====================

Work/Job Package Development

Long- and short-range job planning falls into six phases:

1. Initial Job Screening

a. Assisted by the Maintenance Administrator, the Planner receives all requests with the exception of emergencies for maintenance work (those emergencies that must be performed on the same day as requested will be recorded and passed immediately to the Maintenance Supervisor).

b. Requests are reviewed and screened for completeness, accuracy and necessity:

i. Clear description of request ii. All requestor fields filled in with valid codes

iii. Priority and requested completions are realistic and provide practical lead time

iv. Authorization is proper

--Develops preliminary estimated if required to obtain approval

--Obtains Engineering approval for all alteration and modification requests

v. The requested work is needed:

--Has it already been requested?

--Does it need to be accomplished? If so, does it need to be accomplished at this time?

If questioned, the issue is resolved with the requesting Department or referred to the Maintenance Supervisor.

2. Analysis of Job Requirements. The Planner examines the job to be performed and determines the best way to accomplish the work consulting with the requestor and/or the Maintenance Supervisor as appropriate. In determining job requirements, the Planner:

a. Determines the required level of planning

i. Does this job warrant detailed planning or should it bypass the planning process completely?

ii. Is the effort and cost worth the value to be gained?

b. Visits the job site and analyzes the job in the field. One-third of the Planner's day should be spent in the field:

i. Conferring with the requestor

ii. Clarifying the request and refining the description:

--Where the job is located (machine or location)

--What needs to be done (job content)

--Start and finish points (job scope)

* Finalize priority

c. Visualizing job execution and outlining the requirements

i. Mentally go through and record the steps necessary to execute the job

ii. Prepare sketches or take pictures to clarify intent of the Work Order for assigned mechanics or simply as reference for self during detailed planning iii. Take necessary measurements (exactly)

iv. Determine required conditions. Must this job be coordinated with Production?

--Must equipment be down (major or minor?)

--Define involved control loops

--Will other equipment or adjacent areas be impacted by performance of this job?

--Check for safety hazards.

3. Job Research. The remainder of the planning cycle is normally completed at the planner workstation (two-thirds of the Planner day). During job research, the Planner:

a. Uses Equipment History to determine if the job has been previously performed:

i. When was the last time?

ii. Is it excessively repetitive? If so, consider if anything can be done to avoid recurrence.

--Is this the best solution to the problem?

--Consider the alternative approaches

-- Should additional work be performed in the interest of a more permanent solution?

-- Repair/Replace

-- Make/Buy

-- Consider engineering assistance

--Be conscious of alternate plans for the involved equipment.

b. Refers to planner libraries and to the file of planned jobs to determine if the job or portions thereof have been previously planned

i. Use what you can, avoid redundant effort

ii. Reference the procedures file

-- Determine safety requirements

--Identify necessary tag outs

-- Identify necessary safety inspections, fire watches, and standby positions associated with ladder safety, vessel entry, etc.

iii. Safety must always be a top priority of job planning

c. Talks to other functions with involvement or potential input in the job

i. Is engineering assistance required?

4. Detailed Job Planning. During detailed job planning, the Planner details and sequences job requirements:

a. Selects and describes the best way to perform the job

b. Determines and sequences the job by specific and logical tasks or steps

i. Identifies task dependencies and considers application of PERT or CPM network analysis to facilitate the planning of complex jobs (refer to Section D)

ii. Determines required skill sets for each task (trade and skill level)

iii. Prepares cross work orders to other groups as required and necessitated by the CMMS in place iv. Determines the best method for job performance (the best way to do it)

c. Determines resource requirements

i. Establish the required crew size and labor-hours for each task of the job sequence

--Estimate or apply available benchmarks

--Apply job preparation, travel and PF&D allowances

--Determine if extra travel or job prep is needed

ii. List determinable materials, parts, and special tools required

--Prepare the Bill of Materials

--Establish the acquisition plan

--Determine what items are in stock and reserve them

-- Source those items which must be direct ordered (Purchasing responsibility)

Prepare acquisition documents

Stores Requisition for items in authorized inventory

Purchase Requisition/Order for direct purchases

Work Order for in-house fabrication

Purchase Order with MWO reference for contractors and outside equipment rental

--Don't forget special tools and equipment

Ladders and Scaffolding

Rigging

iii. Determine equipment and external resource needs

iv. Consider disposal issues (expense, time, special handling)

v. Estimate total cost in terms of labor, material and external charges

vi. Coordinate and expedite necessary authorizations based on final cost estimate

--Operational

--Financial

--Engineering

5. Job Preparation. During job preparation, the Planner assembles the planned job package. This package for any given job contains documentation of all planning effort. Given the data contained within the package, coupled with a thorough verbal exchange between Planner and Maintenance Group Supervisor, followed by similar exchange between Supervisor and assigned tradespersons, nothing should be lost between strategic planning and tactical execution of the plan.

a. Complete and detailed Work Order

b. Job plan detail by task

i. Step by step procedures

ii. Site Set-Down Plan (if a significant tear down)

c. Labor deployment plan by trade and skill

i. Labor-hour estimates

ii. Consider contract as well as in-house resources

iii. Consider the use of the GANTT bar chart to help convey task sequencing to assigned crews

iv. Maximize pre-shutdown fabrication and other preparation

d. Bill of Material

e. Acquisition Plan

i. Authorized Inventory vs. Direct Purchase

--Including availability, commitment and staging location

--Make or Buy decision (cost and cost of time considerations)

ii. Required Permits, clearances and Tag Outs to the point feasible and safe (final steps must be taken and verified by the responsible mechanic and equipment operator)

iii. Prints, sketches, digital photographs, special procedures, specifications, sizes, tolerances and other references which the assigned crew is likely to have need of As appropriate, the assembled package is reviewed with the Maintenance Supervisor and the Requestor. The Planner then holds the Planned Job Package for necessary procurements.

6. Procurement. Within the Procurement Process:

a. Purchasing sources all materials requiring direct purchase, obtains necessary competitive bids, obtains delivery dates, and cuts associated purchase orders

i. Monitors and expedites materials/parts delivery

b. Receiving all maintenance materials whether for direct purchases or stock replenishments

c. On basis of the Weekly Master Schedule, the storeroom picks, kits, stages and secures those scheduled job items available from Stores

i. Documents all requisitions via the CMMS ii. Stocks and maintains the Maintenance Storeroom including regular cycle counting to assure continuing accuracy of inventory

The job is released for scheduling only when all required resources (other than labor resources) are on-hand.

Job Plan Requirements

Following is an outline of items that should be included within the job plan text or as part of the job package when the work is scheduled. Not all job plans require all of the listed steps.

1. Purpose of the work order

a. This could include what has taken place already, such as a followup to a repair of breakdown.

b. This could include the initial write-up and who made the observation.

2. Individuals/Departments to be notified

3. Safety-Related Issues.

a. Lockout/ Zero Energy State procedures. (These can be included in the text or as an attached procedure.)

b. Special personal protective equipment (PPE) requirements

c. Required Permits

i. Confined Space ii. Hot Work

d. Special Hazards (chemical or other)

i. Any solvents, chemicals or coatings that may be required

e. Safety Equipment

i. Barricades, fixed or portable (tape or cones)

ii. Signs, Men at Work, Overhead Work iii. Safety harnesses, electrically insulated gloves, etc.

iv. Crane rail stops

4. Special Tools and Equipment

a. Cranes

b. Man-lifts

c. Special Hand Tools

5. Equipment Drawings

a. Engineering

b. Sketches

6. Operation and Maintenance Manual Procedures

a. These can be included in the text or as an attachment, both electronically or hard copy.

7. Job step sequenced procedures.

a. These can be included in the text or as an attached procedure.

b. May list in the text of the step the storeroom part numbers that are not anticipated or ordered but may be required.

8. Specifications and tolerances.

a. Torque requirements

b. Wear Limits

9. Special Instructions

a. Special access sequence, etc.

10. Reference to trade interaction

a. Electricians need to lockout at a special time

b. Riggers will be arriving at a certain time.

11. Testing Requirements

a. Quality checks

12. Clear Lockouts and/or Permits

13. Notify Individuals/Departments work completed and equipment has been returned to service

14. Cleanup and Housekeeping of work area

a. Return special tools to crib, shop area or where necessary

b. Disposition of replaced parts (rebuild-in-house or vendor, trash, hazardous waste, reliability engineering, etc.)

c. Dispose of waste oil

15. Complete paperwork

a. Input time against the work order

b. Make comments on work order

i. Follow up work required

ii. Improvements to the job plan steps

iii. Addition parts that may have been used that need to be added to the equipment bill of materials

c. Turn the completed work order into supervisor/foreman

1.4.3 Estimating and Work Measurement

A necessary ingredient of any operating control system is the generation of quantitative standard information against which to measure and assess performance in the execution of work; to identify areas for corrective action; to measure progress towards goals; and to aid in the decision-making process. The objective of work measurement is to generate this standard information.

Realistic labor estimates are an essential part of a planned maintenance program. There is no effective way of matching workloads against available labor resources without measurement, and it is hard to make realistic promises when taking equipment out of production. Estimates are also essential when determining what the correct manning should be for each grade of labor and what level of crew performance is being attained.

Familiarity with Maintenance Jobs and with Plant Equipment. Some of this familiarity the planner brings to the job, some is acquired on the job.

There is no substitute for task knowledge when it comes to estimating.

A trade background is an ideal starting point; it enables Planners to "visualize" actually doing the job themselves. The next best thing is actually observing what is involved as jobs are worked and, when this is not possible, "talking through" a job with a maintenance tradesperson or supervisor who is familiar with it.

Becoming involved in the job, and being seen as involved, has tremendous advantages. Involvement expands the planner's knowledge of the plant and its equipment. Possibly more important, it builds credibility between the maintenance tradesperson and supervisor for the planner as well as what the planner is doing.

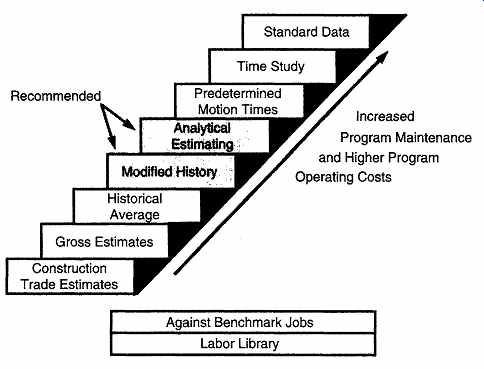

Levels of Maintenance Work Measurement Methodology. Several forms of work measurement, all with varying levels of precision, can be used in the development of job estimates:

1. Supervisor/planner estimates

2. Historical averages

3. Published job estimating tables (construction trades)

4. Adjusted estimates or averages (based on work sampling during a base period)

5. Analytical estimating

6. Time study

7. Predetermined times

8. Predetermined time formulas

The method(s) used depend significantly on the focus of the installation, i.e., Performance Measurement or Schedule Compliance. A Performance Measurement focus (Standard Time + Actual Time = Performance %) requires a more precise form of work measurement.

A Schedule Compliance focus emphasizes early planning and scheduling using less precise forms of work measurement. Analytical Estimating is the preferred form.

Analytical Estimating. Analyzing and estimating maintenance work seems difficult at first because there are nearly always elements that are unpredictable. Normally however, the unpredictable elements do not constitute the whole job and are quite often only a minor part of all that has to be done.

The purpose of analytical estimating is to develop reasonably accurate and consistent time estimates. The technique is relatively straightforward and is quickly mastered. It is based on the following principles:

1. For persons who have had practical experience doing the work, it is easy to visualize and set a time, for simple, short duration jobs.

2. Long, complex jobs cannot be estimated as a whole.

3. Pinpoint accuracy in estimating is not justified or achievable since all the variables in maintenance work cannot be known until after the job is completed.

4. Estimating is easier and more accurate when the job is broken down into separate elements, or steps, and each element is estimated separately.

FIG. 5 Levels of Work Measurement

5. All jobs can be broken down into the following sequences:

--, Getting ready and receiving instructions for doing the job.

This includes receiving job instructions from the supervisor; collecting personal tools together; getting parts from storeroom; collecting special tools and equipment.

Travel to job site.

--, Diagnose/assess problem.

Shut down machine before starting work. This includes finding the line supervisor; stopping the machine using correct sequence; locking out procedure; receiving production input on problem.

-- Partial or total disassembly to get to the problem area.

--, Determine full extent of problem.

Identify replacement parts needed. Look up in parts list and catalogs. Collect from storeroom or special order.

-- Reassemble machine using replacement parts as necessary.

--, Check, test and clean up job site and put away tools.

Travel back to shop.

--, Report on job and return special tools and equipment.

8. Allowances.

Key to Estimate Source for the sequences:

--, -Fixed Provision Table

-Travel Time Table

v -Labor Library

8 -Allowance Table

Allowances. Direct work does not include provision for activities such as preparation, authorized breaks and wash up, fatigue, unavoidable delays, travel, or work balancing on multi-person and multitrade jobs. Such activities are inherent in maintenance work and must be provided for by addition of allowance factors.

Additional Allowances for Specific Situations:

Crew Balancing for Multi-person Jobs=3%

Trade Balancing for Multitrade Jobs=2%

Special Preparation for ?????? =5%

Table 14 Fixed Provision Table

Table 15 Travel Time Table

Table 16 Allowance for Personal, Fatigue and Delay (P, F & D)

Comparative Time Estimating (by making sure everybody compares to the same known): Absolute accuracy is neither possible nor necessary for maintaining an acceptable level of efficiency and control in maintenance. What is essential is consistency.

It is in the nature of human mental processes to estimate by comparison.

We compare the unknown with the known and then estimate the degree of similarity (identical, larger, smaller ... how much?). The tendency is to do this automatically and very subjectively. Some people have an almost infallible sense of comparative size; others find it hard to come within a mile. The basis for consistent estimating is for all planners to have access to and use the same library or catalog of job estimates. There are four basic methods for structuring comparative job estimate files for maintenance work:

1. Systematic files

a. By skill

b. By nature of work

c. By crew size

d. By labor-hours

2. Catalog of standard data for building job estimates

3. Catalog of Benchmark Jobs

4. Labor Library

Current state-of-the-art rests between the last two methods.

Regardless of the comparative approach used, the basic form of work measurement must still be decided. The standards (or estimates) to be loaded into the comparative catalog must first be developed.

The technique of comparative estimating involves the comparison of jobs with those in the library, not the matching of jobs. This distinction is important because in the former case, a few hundred carefully selected jobs will enable an experienced Planner to produce consistent estimates for most maintenance work. In the latter case, many thousands of jobs would be needed to get the same result.

To make a comparative estimate, the planner must (1) define the scope of the job that is to be done and (2) prescribe the method to be used. The planner will need a good knowledge of the process and equipment, and will often have to visit the job site and talk with the operations and maintenance supervisors as well.

The planner's next step is to turn to the appropriate section in the benchmark library to try to find a benchmark with a description similar to the job for which an estimate is required. The planner must then make a judgment based on his or her own mental comparison of what is involved in doing the benchmark job (for which a time is available) and what will probably be involved in doing the job for which an estimate is needed. Final judgment is based on four basic decisions:

1. Is the new job bigger or smaller than the benchmark job it is compared with?

2. Is the difference so small that it will remain in the same time interval?

3. Will it fall into one of the other intervals, either above or below it?

4. Does the new job fall into the next time interval above or below, or two intervals above or below?

Comparative estimating still involves subjective judgment on the part of planners, but the only choice that they need to make is between one time interval and the next. Comparison with library jobs of known duration greatly reduces guesswork on the part of the planner. Maintaining the reference library is a central function requiring the assembly of contributions from all planners to cover the various classes of equipment. In this way, a uniform structure for job estimates can be established and controlled.

1.4.4 Planning Aids

The informational sources required for efficient maintenance planning fall into several categories" Material Libraries filed by each unit of equipment on which maintenance work is performed. The material library supports development of the bill of materials and the material cost estimate.

Labor Libraries filed in some conveniently retrievable manner--normally by unit of equipment, specific type of skill required or by job code. The labor library supports development of job step sequence and the labor cost estimate.

Equipment Records recording all pertinent data for equipment such as installation data, make and model, serial number, vendor capacity, etc.

Equipment Records should not be confused with Equipment History of actual repairs made to the equipment.

Prints, Drawings and Sketches as installed/as modified.

Purchasing--Stores Catalogs providing pertinent information not captured in the material libraries. Even where a materials library is in place, some form of stores catalog or vendor catalogs were used to develop it.

Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) that can be included in planning packages without repetitive documentation effort. Such procedures include safety, lockout, troubleshooting sequences, etc.

Labor Estimating System providing basic data for building job estimates.

Even where a labor library is in place, some form of estimating system was used to develop it.

Planning Package File of previously developed packages for repetitive jobs, enabling repeat usage with minimal repeat planner effort.

Additional reference sources:

1. Catalogs

2. Service Manuals

3. Parts List

4. Storeroom Catalogs

5. Estimating Manual

6. Engineering Files

7. Equipment History

8. Procedural Files

9. Experience

10. Supervisors

11. Reliability Engineers

12. Mechanics

13. Operators

14. Feedback

Labor, Materials and Tool Libraries (Planning Aids). Some planning functions vary each time they are carried out. Others follow the same pattern for each group of identical machines. It is therefore possible to simplify some of the planning processes for machine repair and overhaul by classifying identical groups of machinery and then building libraries of preplanned work element sequences and bills of materials for each class.

The basic concept of these libraries is to take each type of equipment, class by class, and to establish the job sequences necessary to take it completely apart and then put it back together again. Section C, Exhibit C10, provides a filled-in example of a Labor/Materials/Tools Library sheet that shows at a glance for each element:

1. The trades and estimated hours to do the job.

2. The parts involved.

3. The stockroom number of each part.

4. The manufacturer's ID for each part.

5. All special tool and equipment requirements.

Some or all of these sequences are involved in every job done on given equipment. Some additional sequences may be required when parts are repaired rather than replaced, but once these libraries are established:

1. The planner's job is simplified.

2. Every job plan is consistent.

3. There is a good foundation for computer assistance.

A number of sources should be utilized as the situation dictates:

1. equipment history;

2. procedure files;

3. experience;

4. supervisors;

5. reliability engineers;

6. mechanics;

7. operators;

8. feedback.

1.5 The Role of CMMS in Maintenance Planning

Discussions of planning, coordination and scheduling of the maintenance function to this point have been addressed from the "done by hand," or without computer support, perspective. Until recently, maintenance planning was indeed accomplished without computer support. Today, however, with the proliferation of new and improved Computer Managed Maintenance Systems or Computerized Maintenance Management Systems (CMMS) and Enterprise Asset Management (EAM) software, job preparation can be accomplished far more efficiently with computer support.

With the efficacy and tailorability of today's array of information management software, it is no longer cost-effective to manage the maintenance function without computer-managed information access. Computer support is vital to the maintenance control system if cost-competitive posture is to be maintained. Only computer information processing systems that are outputting (reporting) and inputting (updating) data nearly continuously can meet the accuracy and speed required in today's maintenance environment.

Based on the essential and mandatory nature of computer-managed maintenance, information availability to the Maintenance Planner, perhaps the most immediate concern is the establishment of a dialog with the IT Department.

The first step, if it has not previously been integrated, is the setup of the work order system in the (CMMS). All of the WO fields, coding tables and related standardized WO data, to include computer-generated WO number assignment and tracking must be provided to/by the software. It is important in this early stage of Maintenance Planning and Scheduling integration into CMMS that the planners and schedulers not get bogged down in the intricacies of data field design, formatting and related software setup and tailoring. Provide the baseline information and expect IT to take it from there. Periodic sit-downs with IT to evaluate progress and provision will keep the planner up-to-date as well as identify any misdirection in the CMMS work order control system.

If a CMMS is already in place, an equipment database (equipment records) should exist. The accuracy and completeness of these equipment listings (including drill-down access to a breakdown of major components) is often dubious. Elicit the support of the maintenance manager to have the equipment database validated for completeness as well as accuracy. A widely and randomly performed spot check should quickly identify whether problems exist. If the equipment listing does not exist however, the task of setting it up will be much too labor-intensive to be accomplished in-house.

Look to outsourcing to a firm specializing in "CMMS Implementation" to accomplish this and similar data-intense efforts.

Following the validation of the equipment records database and setup of the work order system, attention should be directed toward integrating the backlog management function within the CMMS. WO System setup in CMMS will provide at least 50% of the data needed for backlog management. Providing resource information (updated weekly via the maintenance supervisor's resource availability report) as well as available work status (updated through the work order completion process) gives CMMS nearly all that it needs.

The remaining tools for facilitating the planning and scheduling function involve basic CMMS capabilities. Many CMMS and EAM vendors provide their software in modules that are capable of completely merging with all other modules or elements of their software. If a specific Planning and Scheduling module is not available, they should be able to integrate with a project management program as well as a report generator. The functionalities required include:

1. Storage and Retrieval of:

a. Equipment History

b. Work/Job Plans and Estimates

i. Job Steps

ii. Permit Requirements

iii. Safety Precautions/Steps

c. Current Inventory (and ability to directly requisition or allocate from inventory)

d. Indexed Technical Manual and Drawing Files including locations

2. Computation, Execution, Reporting and Updating For:

a. Life Cycle Cost Analysis Using Integrated Inputs From

i. Maintenance Cost Data (labor, parts, etc.)

ii. Purchasing Data (equipment procurement costs, trade-in value, etc.)

iii. Accounting Data (equipment depreciation rates, etc.)

iv. Production Data (downtime, output quality factor, output rate, etc.)

b. Backlog Size and Composition (available and unavailable)

i. Estimating Capability for Unavailable Backlog size

ii. Alarm (Notification) Point Set (i.e., when available becomes less than 80% of total backlog)

c. Backlog/Resource Balancing calculations

d. Shutdown/Outage Correlation to Available Work (Orders)

e. Work Order Aging including recommended actions (i.e., re-prioritizing, canceling or scheduling)

3. Automation/integration of information flow from control systems and condition-monitoring software*

a. Equipment run-time and startup/shutdown cycles

b. Real time operating conditions (temperature, pressure, flow, etc.)

There are additional benefits to be gained by utilizing the CMMS or EAM to facilitate such things as life cycle cost analysis, work measurement, labor efficiency calculations, failure analysis, maintenance optimization, PdM and CM analysis, PM scheduling and other functionalities that either the Planner or Scheduler, or both, will interface with or otherwise utilize.

[

*Note: Integration of control system and condition monitoring data into CMMS or EAM systems is not a widely offered capability provided by CMMS or EAM software vendors at the time of this writing However, in plants practicing Reliability-Centered Maintenance (RCM) having this feature can be considered essential. The primary purpose of CMMS is to support work management and execution, however, most preventive maintenance (PM) tasks are performed based on calendar- or meter-based schedules and condition monitoring and predictive maintenance technologies are used to analyze equipment condition data to identify potential problems before they occur. Once the need for a PM is identified and either CM or PdM identifies a problem, work orders can then be created in CMMS by keying the information in. Does not this seem to be a logical application for CMMS automation? Meter readings and inspection-point data can be collected on hand-held computers or reported by equipment control systems.

Predictive maintenance analysis software can identify the corrective work required to address a potentially downward trend in an asset's performance.

Alarms generated by monitoring and control system software, through integration with CMMS, can be used to generate emergency work orders.

]

1.6 Feedback

It is important for the Maintenance Planner to know if his planning and work packages are providing the trades with everything they need to perform the work requested on the work order. Even though human nature tends to produce or elicit criticism when things are not right, it is doubtful that criticism of the planner's efforts can produce much improvement since it usually lacks focus. As a result, it is up to the planner not only to elicit feedback regarding his or her performance, but also to give it the focus necessary to enact improvements.

A proven method to measure planning quality is through the use of post-completion feedback and critique. Measuring planning quality must be an ongoing effort. The maintenance manager or planner should hold regularly scheduled meetings, preferably weekly. For efficiency, the feedback meeting could be an agenda line item in the weekly finalization meeting for the maintenance schedule. Periodically the meeting might be chaired by the plant manager to enhance the importance of the meetings. The topics for the feedback portion of these meetings include critique of the recently completed schedule as well as finalization of the upcoming schedule. The critique session is the opportunity to assess planning quality by specifically addressing the questions:

1. Was the schedule successfully completed? What was schedule compliance?

2. Were any of the schedule shortfalls due to incomplete or poor planning?

a. What was the problem?

b. Could it have been avoided?

c. What can we do differently next time?

d. What will it take?

For this process to be successful and meaningful, supervisors must also critique their technicians during and after each job, as a normal and routine element of their on-the-job supervisory responsibilities. Supervisor to planner feedback and even technician to planner feedback should not necessarily have to wait for the weekly managers meeting. Focused or specific feedback should be part of ongoing team effort that occurs at the earliest opportunity and should always be provided in a constructive manner. Some operations solicit mechanic feedback by a Job Plan Survey.

While management can assess the quality of planning by periodically requiring completion of the "Job Plan Survey" the ultimate assessment of planning quality occurs at each periodic work sampling, which quantitatively determines that portion of the trade's effort actually devoted to direct productive work (on-site use of tools/wrench time) and reports improvement trends resulting from planner efforts.

Job Plan Survey User Instructions

The following is intended to instruct maintenance planning supervisors, trade and area maintenance supervisors who supervise work and other personnel who may benefit from use of the job plan survey. The purpose is to gain useful feedback information concerning a job that could be helpful with a particular job or future jobs.

1. Maintenance Planning Supervisors

Maintenance planning supervisors may initiate a job plan survey for selected jobs for the purpose of monitoring quality of job plans. It may be initiated prior to the work and accompany the job order. They may also implement it upon completion of jobs when it is obvious that there have been large deviations from the job plan, resulting in a savings or cost overrun.

2. Work Supervisors

Supervisors responsible for the execution of work should initiate the job plan survey as a means of formal advertisement that a job plan needs or needed improvement and/or changes. It should also be used to identify and highlight reasons for delays, cost overruns, and savings.

3. General

a. When possible, a note should be included on the job order that a job plan survey has been issued and is to be completed.

b. The "Job Planning Survey" form should be completed by the supervisor overseeing the work. The supervisor should seek input and assistance from appropriate hourly technicians.

c. Completed job plan surveys should, whenever possible, be reviewed with the appropriate hourly technician, the supervisor overseeing the labor, the planner and the senior maintenance planner/supervisor.

===================

Job Planning Survey

Your participation in the job plan survey is completely voluntary. Your honest evaluation will be appreciated. Its purpose is to do a better job in planning other jobs.

Trade J/O Planner Work Description Circle or check your response and print explanations as neatly and complete as possible.

1. Job instructions were (clear, vague, misleading, incomplete, other--explain)

2. The estimated work force was (about the right size, too small, too large, other-explain)

3. Actual work performed was (less, more, the same) as the significant work indicated to be performed on the Job Order.

4. How frequently would you estimate that this type of work or job is performed?

5. Were there any unusual or unexpected problems as compared to similar work or doing the job previously? Explain.

6. Were trips made, after the job had commenced, for parts, materials equipment or tools? Y, N,Explain.

7. Were there any problems or delays with permits or having the equipment available to work on? Y , N , Explain.

8. Was the work held up in any way because of other tradework, which needed to be performed first? Y, N,Explain.

Signature Supervisor (Please return completed surveys with job order)

===================

Management Assessment of Planning Quality. Basic questions for management to ask periodically about planning include those that follow.

Yes Question

Are all work orders filled out correctly? Are work orders analyzed in the field? Are supervisors given an opportunity to contribute to the planning and scheduling of work orders? (3 Is the justification for work orders and particularly the lead-time allowed questioned/validated regularly? Are the predetermined materials and equipment needs specified for all work orders? Are estimates demanding but realistic? Is feedback from the supervisors encouraged? Are estimates being steadily refined?

Are the least required number of technician assigned to jobs whenever possible? Are sketches and specifications made when required? Is the planning of work orders up-to-date (i.e., unplanned backlog kept at 20% or less of total)? Are recurring jobs analyzed for the purpose of establishing model work order plans? Are work orders properly coded as to type of work and is the correct authorization obtained? Are daily planning and scheduling visits held with the customers and supervisors according to the procedure? Is shutdown information obtained sufficiently far enough in advance to plan effectively? Are approaching shutdowns given attention soon enough to plan adequately? Are work orders "Closed Waiting for Sign Off" and "Waiting Material" regularly checked as to status? Are contract jobs properly charged to work orders? Is a full day's work scheduled every day for every maintenance person? Is operations notified in advance when to have equipment shutdown or prepared so that it can be worked on without delay? Are daily schedules consistently issued on time? Does the supervisor have faith in the schedule and follow it? Are work orders scheduled according to the priority established by the originator? If a job cannot be scheduled within the desired interval, is the originator notified?

Do daily work schedules account for every technician clearly, including absences? Does the process of scheduling force a review of every job in progress each day? Is the backlog reviewed regularly to identify overdue work orders and action established with the custodian? Are arrangements made with the custodian to establish who will arrange for special safety or entry permits? Is shop work coordinated closely with fieldwork? Are completed work orders promptly returned to the originator to close? Are the necessary labor resources scheduled for minor repairs? Is the effectiveness of the estimates and plans checked after job completion? Is the delivery of predetermined material arranged for in advance? What effort is made to improve material specification and insure its availability on the job when needed? Are preventive maintenance inspection sheets checked and the necessary work orders written and scheduled? Do the work schedules contain a backup of lower priority unscheduled work (2 or 3 fill-in jobs)? Are all PM work orders properly scheduled according to the frequencies established? Is follow-up maintained on all orders for materials? Is the backlog of corrective work orders under control? Is there an environment of order, discipline and efficiency displayed at the planner's desk?

Functional Goals and Measures of Performance. Planner performance is also measured quantitatively, just as maintenance performance, production rate and quality and any number of other plant functions. Properly defined metrics are the ultimate performance measure as they are not swayed by personalities, biases or whimsy. The maintenance planner, the planning function, is gauged by:

--Improved plant conditions and improved use of labor as measured by a reduction of emergencies (goal is 10% of maintenance labor resources).

--Satisfaction of required job completion dates as specifically requested or implied by final priority.

--Improvement in Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF).

--Maintenance of backlogs within specified control limits (Ready between 2 and 4 weeks. Total between 4 and 6 weeks).

--Timely and accurate preparation and distribution of meaningful control reports.

The planner should be assigned 100% to the planning function, and not switched around to fill in for someone who has gone on vacation. The planner must avoid getting involved in unscheduled emergency and urgent work, if he/she is to get any planning done. The first day, from a planner's perspective, is next week.

Summary of a Planned Job. Job planning encompasses the coordination of various job inputs (material, labor, procedural direction and equipment), as required, to achieve a job output of orderly completion at least overall cost. Supervisors are relieved of much indirect activity, enabling them to spend their time more effectively by overseeing the trade crews while the planning function is effectively performed by para-managerial personnel.

Despite being the key to maintenance effectiveness, "planning" has different meanings for different people, depending on background, experience and application. The best understanding is achieved by establishing the criteria of a planned job:

1. Need is shown--a work order exists outlining scope of the work;

2. Analysis is thorough--the job has been broken down to individual components;

3. Required skills--are identified and time estimates made;

4. Material needs--are identified, ordered and on hand for timely availability;

5. Special tools--to perform the job have been gathered;

6. Required specifications and drawings--are at hand;

7. Preparatory and restart-up activities--are listed and prepared for scheduling.

When these planning steps are complete, the job can be scheduled according to priorities established with Operations and others involved the internal customers. When the work is assigned, technicians are productive because delays have been anticipated and forestalled.

1.6.1 Building a History

Maintenance history for specific equipment is one of the foundation elements of maintenance management. It is essential to refinement of the preventive/predictive maintenance program and is the primary tool of reliability engineering in evaluation and analysis of the current program in order to direct necessary refinements. Equipment history also supports the information needs of engineering, operations, accounting and other members of maintenance.

Meaningful and readily usable and retrievable equipment history is dependent upon a thorough, intelligent and consistently utilized equipment numbering system. Equipment history systems that are properly designed and effectively administered facilitate:

--Identification of equipment requiring abnormally high levels of maintenance.

--Analysis of maintenance history for the high maintenance equipment to identify specific repetitive failures to which engineering discipline should be applied to determine how equipment or instrumentation might be modified to reduce premature equipment failures, frequency of repetitive failures, and the general level of required maintenance.

--Comparison of equipment maintenance cost with replacement cost as a tool in capital planning.

--Justification and refinement of the preventive maintenance program.

Equipment maintenance history is primarily the result of data generated from completed work orders. The maintenance management information system (CMMS or EAM) should contain the capability to generate on demand the history of work order activity for any piece of equipment to which unique identification has been assigned. There is also a growing trend that includes specified production data (e.g., production capacity--dates, manufactured product lot numbers, etc.) in the Equipment History. In the event of post-consumer identified quality problems, the production data contained in Equipment Histories can be invaluable to Reliability Engineering.

Retrieval of both maintenance and production history constitutes an important analytical tool by which reliability engineers analyze significant maintenance trends, predict problems that are developing and identify equipment modification or redesign criteria. Resultant corrective actions of the analytical process include improved repair procedures, replacements, modifications, upgrade and redesign and adjustments to content or frequency of the PM/PDM program.

To provide for the accumulation of equipment history, it is necessary to establish a reference (numbering) system to identify processes, equipment, components, instrumentation loops devices, etc., for which it is believed that history would be useful. The equipment numbering system is also the CMMS first-order identifier of plant equipment and therefore should be developed jointly by Maintenance and IT personnel. Although it might be desirable to maintain data on every item and component of equipment and instrumentation, the benefits to be derived are not worth the administrative effort to collect such information. To avoid such a situation, the following criteria are applicable when defining items requiring assignment of an equipment identification number:

--item is readily identifiable;

--item is large enough to be meaningful, yet discrete enough to permit accumulation of valid data;

--item is one where preventive or predictive maintenance requirements currently exist or are anticipated;

--item is one where maintenance cost and repair histories would be of value to engineering, maintenance, operations, accounting or others.

Assigning a number to a specific part within a component is excessive.

The level of detail can be derived from work order descriptions and/or from stock usage records. However, the identification of the point where equipment-numbering stops must be clear so that items from that point are picked up within the work order description. This understanding must be conveyed to all personnel authorized to originate work order requests.

Although they are often confused, the equipment history and the equipment record differ.

Equipment History has been discussed above. It contains a database of work orders, and possibly production data, completed against specific equipment, listed by Equipment Numbers assigned in accordance with the chosen and designed CMMS numbering scheme. Some systems accumulate all work orders; others accumulate only significant work orders. In traditional manual systems, equipment history was commonly referred to as "the fat files." The fattest file was where maintenance engineers focused their attention.

Equipment Records contain nameplate, technical and original installation data, also listed by Equipment Numbers assigned in accordance with the chosen CMMS numbering scheme, for every piece of equipment.

Equipment Records must be updated, whenever equipment is modified, replaced or completely overhauled, with details of the configuration change, cost information, dates, etc. Together with Equipment History, these two databases provide a complete record of the equipment Life Cycle and Life Cycle Costs.

History information on equipment maintenance is typically sought in two forms:

1. Installed location: the primary data-gathering form for maintenance information as well as cost accounting.

a. Equipment history is primarily concerned with the magnitude and nature of repairs at a specific process point, as the atmosphere, application and usage at the installed location is normally the principal reason for high maintenance cost.

b. To support various control systems, work order costs must be charged to a proper account to accumulate costs by that organizational unit most directly responsible for the magnitude of required maintenance.

2. Specific equipment unit: As the repair/replace decision is normally related to a specific unit, this secondary sort of equipment history is also desirable. It requires accumulation by unit regardless of where the unit may be installed. Unit accumulation should be selective, but careful design of the computerized work order system, coupled with effective equipment identification coding, can yield both sorts of equipment history as needed.

Equipment History (What and Why)

--Equipment history is a foundation element of maintenance management. It is a primary tool of reliability engineering.

--Identification of equipment requiring abnormally high levels of maintenance.

--Analysis to identify specific repetitive failures.

--Comparison of maintenance cost with replacement cost.

--Justification and refinement of the PM program.

--To evaluate maintenance failure trends in order to direct corrective action, reliability engineers need reliable, meaningful and detailed history of repairs.

-- Equipment history, equipment records and equipment downtime reporting are often confused: o Equipment History is a maintenance-engineering tool.

- Equipment Records are a planning tool.

--History also supports the informational needs of engineering, operations, accounting and other members of maintenance.

From the foregoing, seven essential elements for effective Equipment History can be identified:

1. An effective equipment numbering system:

a. Installed location.

b. Specific equipment unit.

2. A well designed and administered work order system.

3. Effective cost distribution to work orders (labor, materials and contractors).

4. Accurate downtime reporting.

5. Meaningful and consistent work descriptions.

6. Ease of information retrieval.

7. Reliability Engineering to make effective use of the information base.

PREV. | NEXT | Article Index | HOME