AMAZON multi-meters discounts AMAZON oscilloscope discounts

Depending on how you define "Planning Maintenance" and "Scheduling Maintenance," the origin of Planner/Schedulers can vary significantly.

Earlier, it was pointed out that pre- and post-flight checks on military, and commercial aircraft had their origins in First World War. The aircraft branches of the military continued to lead the evolving practice of maintenance with their adoption, in the 1930s, of standardized, periodic inspections --the 30-, 60-, 90-, 120-hour (flight time) inspections of airframes and aircraft engines. Each increasing hourly-based inspection involved an increasingly detailed level-of-inspection, and ultimately arriving at complete disassembly for individual part inspection and (as required) replacement.

1. IN THE BEGINNING

These flight-time based inspections brought about the first requirement for skilled planning and scheduling. Because of the practice of swapping out aircraft engines from planes with heavily damaged fuselages, it was a routine occurrence for the 120-hour inspections of the airframe and engine on one aircraft to come due at different times. This meant that aircraft were taken off-line twice as often as they would have been with coincident airframe and engine 120-hour inspections. Additionally, because the military had this tendency to fly all their aircraft on every mission, most aircraft would come due for their major inspections simultaneously. This, of course, would result in the entire squadron being "off-line" rather than just one or two aircrafts.

The flight-hour-based inspections required some planning skill to keep airframe and engine inspections synchronized and even more skill at maintaining staggered off-line schedules for squadron aircraft. The engine swapping practice had to be modified to attempt to keep like inspection intervals of mated airframes and engines. Similarly, it was often necessary to "fly aircraft into checks." This was the practice of forcing the hourly inspections to occur on each aircraft at their pre-planned times by either creating additional flight hours by assigning training flights or single aircraft sorties to pre-selected aircraft or reducing flight hours by "sitting-out" a mission.

The goal was to avoid taking more than one aircraft off-line for a major inspection at a time. This manipulation of parts and flying time sometimes required extraordinary chart, record and time-line development and tracking in order to meet the "one aircraft at a time" goal. Soon, aircraft squadron maintenance officers were given special training in order to sharpen these skills. These were the first Maintenance Planning and Scheduling Workshops. A point worth making here is that the jobs of maintenance planning and maintenance scheduling, as they exist in modern manufacturing plants today, are at least 100-fold more complex than the job of the aircraft squadron maintenance officers of the 1930s and 1940s.

In the 1950s, the U.S. Navy was ordered to adapt the maintenance practices of the Air Force for shipboard use or develop their own system for effectively maintaining fleet readiness. The result was the 3M (Maintenance and Material Management) System for maintenance of shipboard systems and equipment. Maintenance Requirement Cards (MRCs) that provided procedural steps for performing periodic maintenance actions were developed at a headquarters level office along with maintenance requirement listings that identified all maintenance requirements, in frequency sequence, for individual shipboard equipment installations and system suites. At the ship level, updates for equipment maintenance plans were received on a quarterly basis and as equipment modifications were installed. Each shipboard division officer transcribed the periodic maintenance requirements onto large poster-board schedules, incorporating the ship's operating plan into each schedule. Various maintenance actions required the ship to be in port, at sea or in some other special configuration (e.g., full speed operations). Ship operating plans drove these schedules by either allowing or prohibiting certain requisite conditions for applicable maintenance requirements. In this role, the division officer was the closest yet in function to today's manufacturing plant maintenance planner. Today, although the Navy still refers to it as the 3M system, it has evolved tremendously. The basic document describing the system--the 3M Manual --is more than 400 pages in length and covers the use of computer scheduling, Reliability-Centered Maintenance and similar updated maintenance methodologies.

A part of the Navy's 3M System was the correlation of maintenance and repair actions to one of three levels of the ship repair hierarchy:

1. Operational (shipboard level);

2. Intermediate (in port at a repair command or alongside a repair ship or tender) and

3. Depot (shipyard level repairs, modifications and ship overhauls).

The two additional levels, Intermediate and Depot, were scheduled for a duration determined by the number and size of the work packages designated for accomplishment. The objective was to make the availabilities at these two repair levels only as long as was absolutely necessary to complete the work, so the ship could be deployed again as quickly as possible. This kind of "tight as possible" scheduling eventually gave rise to the application of Critical Path Method (CPM) and Project Evaluation and Review Technique (PERT) for scheduling and project management methodologies (see Section 8 for a description of the history and use of these methods.

Section D also provides a brief tutorial on constructing and analyzing CPM Schedules). Both methods for scheduling and managing maintenance activities are used today in the manufacturing industry.

2. DEVELOPING STANDARD PRACTICES

Up to this point, the various historical predecessors to modern Maintenance Planners performed in a variety of roles with a variety of functions and responsibilities. In today's manufacturing environment, the requirements for maintenance planners have become much broader in scope and more complex in execution. This situation has often led to modification of Planning and Scheduling responsibilities to parallel the skill level of the individual assigned as the planner. The entire maintenance operation suffered as a result. There is a fundamental process for maintenance planning and scheduling, and depending on the unique variables at every plant or facility, additional process requirements may be assigned to the planning and scheduling function. However, dropping any of the fundamentals would be detriment of the overall maintenance function, as would the assignment of additional requirements that could supersede or detract from the primary planning and scheduling function.

2.1 Basic Process

There are specific goals and objectives associated with maintenance planning and scheduling (see Section 3). Achieving them defines a basic planning and scheduling process. In the following paragraphs, the goals and objectives of the Maintenance Planner/Scheduler are used to derive a basic planning and a basic scheduling process. These are defined as Minimum Standard Practices of the Maintenance Planner --Scheduler. As stated previously, of all Maintenance Organization's activities, Planning and Scheduling have the most profound effect on timely and effective accomplishment of maintenance work. In order to achieve the level of Planning and Scheduling performance necessary for a truly effective maintenance operation and to ensure consistency of performance across time and people, the development of a Maintenance Department Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for the Maintenance Planning and Maintenance Scheduling process is required (see Section C for a Planning and Scheduling-SOP template). Sound Planning and Scheduling practices are the starting point for an effective maintenance operation.

Only well-defined maintenance tasks can be planned.

Only well-planned work packages can be scheduled.

The basic goal of the Maintenance Planner is the avoidance of delay, which defines the planner's position and role.

Position and Role: The role of the Maintenance Planner/Scheduler (P/S) is to improve work force productivity and work quality by anticipating and eliminating potential delays through planning and coordination of personnel, parts and material and equipment access. The P/S is a pivotal position in the maintenance operation and who maintains a continuous dialogue between Operations and Maintenance. The P/S is responsible for planning, scheduling and coordination of all maintenance work (that can be planned) performed on the plant site.

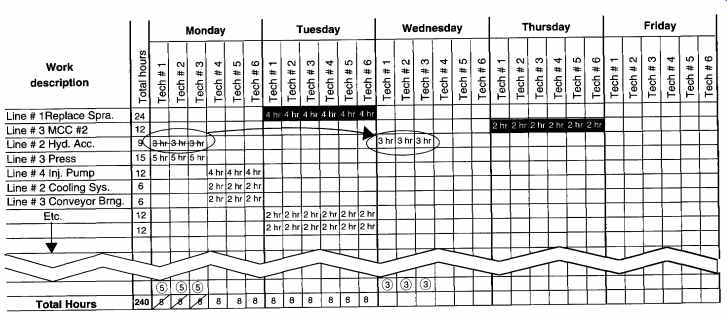

In order to achieve the six primary objectives of the Maintenance P/S, the planner's responsibilities and duties require a thorough knowledge of the maintenance operation as well as several additional skills. Maintenance Planning and scheduling is the hub from which all maintenance activity, that can be planned is coordinated. Planning and Scheduling are the processes for defining how and when a job is to be performed and what resources will be required. It involves a broad spectrum of activity.

The P/S must know the job well enough that he or she can describe what is to be accomplished and can estimate how many labor-hours will be required. If the P/S does not know the requirements, the assigned crew will not know their expectations. In performance of their duties, the P/S is:

-- The representative of the Maintenance Manager and principal contact and liaison path between Maintenance and Operations as well as other supporting and supported departments. In this capacity, the P/S ensures that all internal customers of Maintenance receive timely, efficient and quality service. He also maintains a continuing interest in the internal customer's needs. The P/S has a keen awareness of the customer's situation (schedule, problems, etc.), and therefore is able to help Operations balance their need for daily output with their need for equipment reliability through proactive maintenance.

-- Responsible for long-range as well as short-range planning. Long-range planning involves the regular analysis of backlog relative to available resources. These two basic variables must be kept in balance if a proactive maintenance environment is to be established and sustained. The P/S is also responsible for maintaining records and files essential for meaningful analysis and reporting of maintenance related matters.

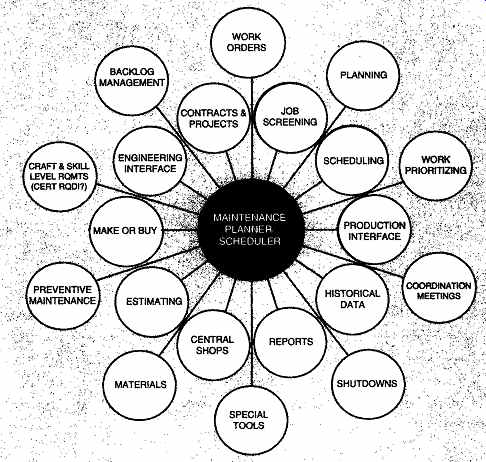

The primary activities of work planning are the identification of all technical and administrative requirements for a work activity and provision of the materials, tools and support activities needed to perform the work.

FIG. 1 Planner/Scheduler Interfaces, Activities and Responsibilities

These items should be provided to tradespersons in an easy-to-use, complete work package. Effective planning should help ensure that consistent quality maintenance activities are conducted safely and correctly. Work planning is a finite, well-defined process (well defined by a Maintenance Department Standard Operating Procedure) that should be periodically assessed through field observation of work being performed. Direct feedback from the tradespersons (either via or in company with their immediate supervisor) to the planners should be a fundamental tool for improving the planning function and ensuring its adequacy. Thus, the "basic" maintenance planning process consists of three steps as shown in FIG. 2.

Scheduling of corrective and preventive maintenance and of planned and forced outage work is necessary to ensure that maintenance is conducted efficiently and within prescribed time limits. Scheduling daily activities based on accurate planning estimates should improve the use of time-on-the-job.

Maintenance scheduling during planned outages is important to support the return of the plant to service on schedule (and within the approved budget) and results in improved availability and capacity factors. A contingency schedule should be maintained so that if a forced outage occurs, the forced outage time is minimized and effectively used, and all needed maintenance is performed prior to restart.

FIG. 2 Basic Maintenance Planning Process

An effective schedule should assist management in controlling and directing maintenance activities and should enhance the ability to assess progress.

The schedule should reflect the long-range plan and day-to-day activities.

Effective scheduling should enhance the efficient use of resources significantly by decreasing duplication of support work, decreasing maintenance technician idle time and ensuring completion of planned tasks. The schedule should be the road map for reaching plant maintenance goals.

Scheduling, as the execution phase for planned maintenance tasks, is an integral part of the overall preparation for maintenance activities and should be performed in close coordination with planning activities. The completed and fully integrated schedule should be based upon details such as work scope, importance to plant goals, prerequisites and interrelations, work location and resources and constraints identified and developed during the planning process.

Effective daily schedules are needed to implement the maintenance activity plans represented by the integrated schedule. Management should track and periodically assess performance according to the daily schedule.

Effectiveness of the daily scheduling process during normal operation should be a good indicator of how effective the daily schedule may be during major outages.

The integrated schedule should be reviewed by those responsible for implementation. It should be accepted and widely used by personnel involved in maintenance activities. Preparation of contingency schedules should decrease the time necessary to respond to problems or unforeseen perturbations, if they occur, and increase the information available for decision-making.

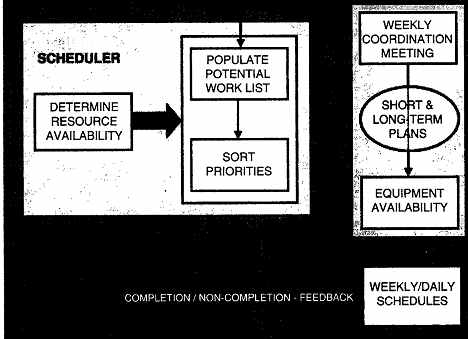

The basic process (see FIG. 3) for preparing maintenance schedules is as follows:

1. The P/S determines, by discussion with the Supervisor and referring to vacation charts, the resources available and the expected total working hours during the schedule week.

2. The P/S reviews work orders from all sources that are "Ready to Schedule" then from personal knowledge, or after discussions with the operations supervisor, and arranges the work orders into priority order.

3. The P/S lists each work order on the schedule form.

4. Moderate Weekly Schedule Coordination

Meeting to achieve a consensus between equipment custodians and maintenance/engineering supervisors as to the most effective near-term deployment of available maintenance resources.

5. Prepare and publish the approved weekly schedule. The crew supervisor performs daily Scheduling to coordinate new high-priority work orders with those already in the weekly plan. Always striving to optimize schedule compliance despite essential schedule "breakers."

6. Schedule Follow-up to determine the level of schedule compliance and reasons for completion shortfalls. This is a "constructive" step towards future improvement.

FIG. 3 Basic Maintenance Scheduling Process

2.2 Manufacturing's Influence

The manufacturing industry has unquestionably exerted the most influence on the function of the Maintenance Planner. The very nature of manufacturing creates a regular plethora of obstacles to straightforward planning and scheduling of maintenance tasks. The emphasis on steady and continuous operation of production equipment is the most significant obstacle.

Operations managers have always demonstrated a reluctance (and still do so) to take production equipment offline "merely to perform maintenance." Fortunately, Lean Thinking has taught production oriented managers that improved equipment reliability through Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) can actually increase the net online time for production line equipment. Nonetheless, production schedules are still sacred cows and variations due to poorly planned maintenance activities are not well received.

Other characteristics of manufacturing operations in particular, lean manufacturing operations that tend to unsettle maintenance planning include:

-- Pull System or Continuous Flow

-- Interdependency of equipment in a production line

-- Breakdowns

-- Setup time

-- Non-staggered offline periods

-- Dynamic production schedules

The most difficult situation that the Maintenance Planner faces is the potential for large variations in workload. For example, when all production equipment in a particular assembly or production line goes offline at a single time and within a short period of time, it produces the dilemma of maximum workload for a short amount of the total workweek and no workload for the remainder of the workweek. Yet a responsibility of the Maintenance Planner is creation of a steady workload for maintenance staffers.

2.2.1 Accommodating a Varying Workload

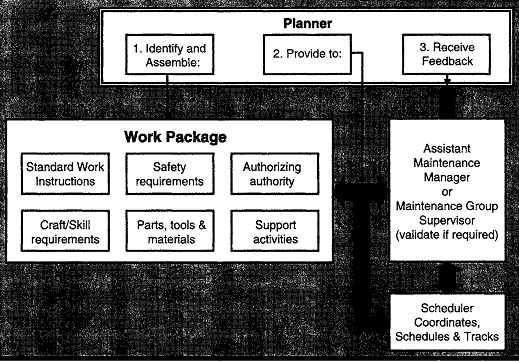

Accommodating (Accommodating (1: to make fit, suitable, or congruous 2: to bring into agreement or concord." RECONCILE) a varying workload is only possible through the weekly schedule coordination meeting with operations. For example, a Planner must schedule maintenance work for six maintenance technicians for the following week. To simplify this example, assume that all technicians have the same skills and qualifications; the Planner must identify and schedule six x 40 hours, or 240 labor-hours of maintenance tasks. Operations has already provided the Planner with an equipment availability schedule for the following week. Line # 1 will be available, in its entirety, on Tuesday from 8:00 AM until 12:00 PM and Motor Control Center # 2 for Line # 3 will be offline on Thursday from 2:00 PM until 4:00 PM. The planner checks the "Ready Backlog" of work orders and sure enough, there are 160 labor-hours of work for Line # 1 and 80 labor-hours of work for Line # 3's MCC # 2--exactly 240 labor-hours. The only problem is that six employees just cannot produce 160 hours of labor in a four-hour period; they are pretty much tapped out at 24 labor-hours.

That is where the Maintenance Schedule Coordination Meeting comes in.

The Planner comes into the meeting armed with his preliminary "ready to schedule" or "available backlog" work list and operation's equipment availability schedule and proceeds to negotiate for additional equipment availability windows. FIG. 4 shows the work orders scheduled for the operation--provided availability schedule in the darkened blocks. The availability windows that need to be negotiated are the un-shaded blocks outlined in bold with labor-hours filled in (only Monday and Tuesday are illustrated but the same process is applied for Wednesday through Friday). Of course, there may be overriding reasons that operations cannot take an indicated system/equipment offline, so the planner must have additional ready to schedule work in reserve to replace that work that is unable to be scheduled. Additionally, for example, operations may not be able to take Line # 2 Hydraulic system offline on Monday, but will be able to make it available Wednesday afternoon.

The weekly schedule coordination meeting is a give-and-take cooperative effort to achieve the best fit for maintenance work and operations' schedules.

The planner must be armed with sufficient backup work to accommodate operations-driven perturbations to his preliminary schedule. A word of caution is necessary here. Planning is done prior to scheduling. If schedule coordination is an operations dictatorship such that a sizable portion of planned work is deemed "not possible" by operations, then the planner must plan for much more work than can be accomplished, simply as a contingency pool of backup work. Work planning is a detailed, time consuming and labor-intensive effort. It is done for work that needs to be performed. Planned work should not be considered as a frivolous effort that can be discarded out-of-hand either by operations or by the scheduler. Every effort should be made to stick to the preliminary schedule presented at the schedule coordination meeting.

The fact that the scheduler should be armed with sufficient backup work to accommodate operations-induced schedule perturbations means that the scheduler should have one or two jobs in backup in the unlikely event that it is truly impossible to take a piece of equipment offline for maintenance.

Not all maintenance work requires equipment to be shut down or taken offline. Much of the weekly schedule will involve maintenance on running machinery; operating tests and measurements, inspection, predictive maintenance (PdM) and sampling are a few examples. Even though production equipment may not be required to be taken offline for this kind of maintenance work, coordination and finite scheduling is still a requirement.

In summary, it is important to reemphasize that the processes and examples just covered were the basics. They were intended to provide a concise overview of the Maintenance Planning and Maintenance.

Scheduling functions. There is, in fact, much more involved in both functions, lest you become too complacent and decide that the Maintenance Planning and Scheduling effort is considerably easier than you thought.

Sections 6 and 7 will drill down to the details and provide the comprehensive processes and considerations that constitute Planning and Scheduling respectively.

2.2.2 Resources, Resources, Resources

In general, there seldom exists a scarcity of work to be planned and scheduled. The scarcities are normally associated with resources such as labor, material, technical documentation, procedural documentation, etc.

Within resources, the most common and critical shortfall is labor. Before work can be either planned or scheduled, the maintenance P/S must know what resources are available to execute the work. The most effective method for the P/S to gain accurate information regarding labor resources is through the use of a weekly Labor Resource Report (LRR). The Labor Resource Report (see Section C for a sample LRR Form) should be submitted to the planner by each maintenance crew/team supervisor on Monday of the week prior to the period covered by the report. The LRR is much more than just a vacation schedule. Everyone knows that, even in a Lean Operating environment, there are many more demands on an employee's time than just work. Breaks, committees, meetings, training and a host of other things will detract from an employee's time available to work. Supervisors must account for all of these detractors, and specific time periods where applicable, in their weekly LRR to the maintenance P/S. Additional resources required for efficient maintenance planning fall into several categories: Material Libraries filed by each unit of equipment on which maintenance work is performed. The material library supports development of the bill of materials (BOMs) and the material cost estimate.

Labor Libraries filed in some conveniently retrievable manner --normally by unit of equipment, specific type of skill required, or by job code.

The labor library supports development of job step sequence and the labor cost estimate.

Note: The content, development and use of these specialized planning "libraries" will be covered in detail in Section 7.

Equipment Records recording all pertinent data for equipment such as installation data, make and model, serial number, manufacturing, capacity, etc. Equipment Records should not be confused with Equipment History of actual repairs made to the equipment.

Prints, Drawings and Sketches as installed.

Purchasing --Stores Catalogs provide pertinent information not captured in the material libraries. Even where a materials library is in place, some form of stores catalog or vendor catalogs are used to develop it.

Standard Operating Procedures can be included in planning packages without repetitive documentation effort. Such procedures include safety, lockout, troubleshooting sequences, etc.

Labor Estimating System provides basic data for building job estimates.

Even where a labor library is in place, some form of estimating system is used to develop it.

Planning Package File of previously developed packages for recurring jobs enables repeat usage with minimal repeat planner effort.

Additional Resources

- 1. Catalogs

- 2. Procedural Files

- 3. Service Manuals/Vendor Maintenance Bulletins

- 4. Equipment Parts Lists

- 5. Storeroom Catalogs

- 6. Estimating Manual(s)

- 7. Engineering Files

- 8. Equipment History

2.3 Appearance of Balance

Work planned and scheduled on the integrated weekly schedule should achieve a balance of maintenance activities in order to keep the various maintenance groups working at a steady pace and without long idle periods.

At the same time, as pointed out earlier, the scheduling function is also meant to help Operations balance their need for daily output with their need for equipment reliability through proactive maintenance. A final balancing effort that the scheduler needs to perform is managing the backlog of work at a predetermined level, while allowing for unplanned and nonrecurring maintenance activities. Balance must be achieved for maintenance resources to respond to breakdowns that might occur during the planned work schedule period and other activities such as special maintenance engineering investigations, investigation of out-of-range predictive maintenance results and a multitude of other irregular frequency maintenance activities. This all may sound like a balancing act worthy of a circus performer; in fact, it is a balancing act requiring considerably more skills than even the most talented circus performer might possess.

Achieving this balance requires adherence to some time-proven scheduling considerations, principles and procedures such as:

1. Lead time--needed work must be identified as far in advance as possible so that the backlog of work is known and jobs can be effectively planned prior to scheduling.

2. Work Backlog must be kept within a reasonable range. Backlog below minimum does not provide a sufficient volume of work to accommodate smooth scheduling. Backlog above maximum turns so slowly that it is impossible to meet customer needs on a timely basis.

3. Special or heavy demands cannot be scheduled unless backlog is addressed by providing additional resources or by relaxing priorities.

4. Jobs cannot be scheduled until all needs (parts, materials, tools, special equipment, the item to be worked, any special support) are available in the quantity required and at the time necessary.

5. Each available maintenance technician must be scheduled for a full day of productive work each and every day.

6. Emergency work may need to be done at the expense of scheduled jobs. The displaced scheduled jobs would constitute an overloaded schedule and result in work being carried over to the next schedule period unless addressed by a temporary increase in capacity, i.e., overtime.

7. Additional work (amounting to 10-15% of available scheduled manpower), should be identified and listed as fill-in for situations where scheduled jobs cannot be performed for a legitimate reason or other scheduled jobs have been completed in less time than planned. This 10-15% is not included in the schedule compliance calculation.

By adhering to these principles and considerations, the P/S ensures that:

-- all maintenance needs are properly attended to;

-- accurate evaluations are made as to the importance of each job with respect to the operation as a whole;

-- customers have their work performed on a timely basis;

-- equipment offline time experiences no, or minimum, delays;

-- work is performed safely;

-- overall maintenance cost is kept to a minimum.

Experience from the last 10 to 15 years has shown a relatively repeatable mix of maintenance work in a balanced backlog. The work mix is shown in Table 1. The table is provided for information purposes only and the numbers should not be considered as targets for the scheduling of planned work.

Table 1 Typical Balanced Backlog

Every plant will have different influences on defining a balanced backlog of maintenance work. Local determination of what constitutes a balanced backlog of work should be made in order to recognize when the mix of work is out of balance, which indicates a process problem possibly requiring an investigation. When the considerations above are applied and the scheduling guidance of Section 7 is followed, a balanced backlog will result that contains whatever mix of work that is appropriate for your plant.

PREV. | NEXT | Article Index | HOME