AMAZON multi-meters discounts AMAZON oscilloscope discounts

Kinds of Incentive Ordinarily Used. Many applications of incentive bonus payments have been made other than those based on direct measured standard times for the work involved. An incentive plan based on measured standards requires the highest management ability in the development and installation of all cost-control functions: methods, planning and scheduling (equipment, materials, and workers), work-measurement standards, and accounting procedures. It also requires the highest management ability in the administration of these control functions from the time the work is authorized until incentive bonus is paid for the efficient completion of the work. These cost-control functions are essential to good management and are necessary with or without incentive payment. The addition of incentive pay on top of cost-control functions might truly be considered as a "fringe" benefit in the reduction of maintenance costs. Wage incentives are not a cost-control function, but a method of rewarding worker efficiency and management efficiency. The direct-measurement-type plan is discussed in further detail later.

Other applications of bonus payments include:

1. Ratio plans-maintenance hours (or dollars) to items such as manufacturing labor hours (or dollars), net sales dollars, and factory cost dollars.

2. Ratio plans-equipment-operating hours to downtime hours.

3. Bonus to maintenance workers based on production efficiency.

4. Work-load-type bonus plan; established primarily for assigned maintenance personnel in areas or on specific equipment. This type of plan will be discussed in detail under Kinds of Maintenance

Work for Which Incentive Pay Is Appropriate. A typical ratio plan could be developed and administered in the following manner, using the ratio of maintenance-labor dollars to total manufacturing-labor dollars as an example:

-------------

Development of plan | Example

1. Select a base period to establish ratio

Approx. 2 years

2. Determine from cost data the ratio of

Maintenance 12%, manufacturing labor 88% maintenance-labor dollars to manufacturing-labor dollars

3. Determine share of gains maintenance 50% labor is to receive

4. Determine pay method

On an accounting-period basis, 75% of bonus paid immediately, 25% held for deficit periods

-----------------

Payment of Plan. Using the examples as listed in the table for items 2, 3, and 4 under Development of Plan, the following hypothetical figures show the basic concept of payment method for a ratio plan.

The comments made here in regard to the development of, and plan of payment for, a ratio incentive plan are by necessity general. There can be no "store-bought" ratio plan. Each one must be tailored to the individual specifications of the organization concerned. The apparent simplicity of such a plan is deceiving. Each step in the development and administration of this type of plan depends on the validity of the previous step upon which it is based. The following points are particularly critical:

---------

Step in development and administration Second accounting period Year to date

A. Total cost of manufacturing and maintenance labor $333,000 $623,000

B. Standard maintenance cost (A _ 0.12 _ B) 39,960 74,760

C. Actual maintenance cost 35,640 66,410 D. Variance (B _ C _ D) 4,320 8,350 E. Incentive earnings (D _ 0.50 _ E) 2,160 4,175 F. Amount to deficit fund (E _ 0.25 _ F) 540 1,044 G. Available for distribution (E _ F _ G) 1,620 3,131

----------

1. Be certain that a valid ratio exists upon which incentive payments can be based. A good rule--the longer the length of time for which the ratio has existed, the more probable its accuracy.

2. Take care in determining the percentage of realized savings to be made available as incentive payments. Such payments should be made only to the extent that the recipients can control the vari able factors involved. But they must also be inviting enough to furnish the desired pull.

3. Do not install any such plan without including in the basic agreement the machinery to adjust the base ratio for changes, such as technological improvements which will occur. It is advisable, in order to keep such adjustments to a minimum, that no changes less than 5 percent (which may be cumulative) be cause to adjust the base ratio.

4. Foresee the possibility of deficit periods existing and provide a means to fill these gaps.

These ratio plans have the following advantages:

1. They are not profit sharing. There is some basis for measurement.

2. There are no time studies involved.

3. There is no added administration cost beyond good cost-accounting procedures.

4. Not all the gains go to the employees, since there are also management contributions.

5. In those instances where the plan is accepted and functioning, management is forced into efficient cost-control functions such as planning and scheduling, material control, and improved methods, by worker pressure.

6. There is an incentive to the workers to use all the ingenuity and resourcefulness available to complete the job efficiently. Under the individual incentive system this is not usually the case as a change of standard is the end result.

7. This type of plan encourages group participation and has in some cases broken through craft barriers.

8. It tends to control waste and scrap which result in excess labor costs.

9. It provides an opportunity for maintenance workers to increase their earnings.

This plan has disadvantages that require careful administration to preserve the incentive aspects:

1. If the base of this plan is not quickly and accurately adjusted for outside influences that are beyond the worker's control, such as the effect of capital improvements, product mixes, number of shifts in operation, the production rate, sales price, or other changes not included in the base calculations, the plan will fail. If the union has shared in developing the base and the administration of the plan, these adjustments to the base could create the same problems as wage reopeners, a wage-negotiation session every time there is a change in the base ratio.

2. There are also disadvantages as far as employee relations are concerned. An incentive plan to be effective must pay off. Since the base consists of averages, there could be accounting periods when bonus would not be earned. There is no direct relationship between effort and bonus, and the same amount of effort, or more, could have been used during the period which did not pay off as during the period which did pay off. This situation is difficult to explain to the workers. In addition, it makes necessary a continual selling program on the worth of the plan. This selling pro gram does not exist to such a degree with direct measured standards, where good administration and the relation of effort to pay are the items that do the selling.

3. The computations required to adjust base ratios for the effect of major capital improvements, new products, or new sales prices (depending on type ratio) will of necessity be based on estimates and projections. The degree of accuracy of these estimates to future maintenance cost experience will be questionable.

4. Unless this ratio plan is supplemented by some basic manning or work standards, there will still be considerable loss of maintenance labor.

5. If this plan is installed in a plant with low maintenance efficiency, bonus payments could be made on substandard performance that could be completely out of line with effort output and bonus paid production workers. That would create problems with production incentive pay.

It is evident that the chance of success of a ratio plan is more favorable in a plant that has a relatively stable volume, a fairly constant product mix, few process changes, and fairly well-established maintenance cost-control measures already in effect.

Plans based on operating to downtime ratios are usually based on historical records of lost time due to machine delays caused by defective maintenance and paid to assigned or preventive-maintenance crews. A bonus payment of 20 to 30 percent is usually added to the hourly wage rate of maintenance men. When machine delays occur, a predetermined bonus penalty is deducted from the 20 to 30 percent bonus possibility. This is a very difficult type of plan to administer because of the necessity to provide effective maintenance. The only working relationship it could lead to between management and maintenance workers would be one of constant friction. This method of paying bonus is also very poor from a psychological viewpoint. It is virtually impossible to give a promise of 20 to 30 percent bonus and then deduct from it without tangible proof of negligence.

This type of plan is normally used as a supplement to other kinds of incentive plans that cover shop and plant standard maintenance work. It lacks any type of measurement that could determine the number of maintenance hours required to perform the work.

A bonus based on production efficiency is nothing more than a method of adjusting pay. While it may be true that there is a relationship between the efficiency of direct labor and maintenance, in most cases the entire control of maintenance bonus is in the hands of production operators. There will be no incentive pull of maintenance workers. From a practical viewpoint the only advantage would be in the adjustment of maintenance wages, keeping them in line with production wages. In addition to applying the method of pay to the entire maintenance group, this type of bonus payment is used as a supplement to other types of incentive plans covering shop and plant maintenance work.

Without a method of work measurement, there is no value beyond solving a pay-discrimination problem that might arise from unskilled take-out pay exceeding that of the skilled take-out pay.

Kinds of Maintenance Work for Which Incentive Pay Is Appropriate. There are three broad classifications of work in maintenance:

1. Direct craft workers in shop or plant.

2. Assigned maintenance workers who are mainly troubleshooters and work on numerous small repair jobs within specific areas or on specific equipment.

3. Service personnel, such as storekeepers and toolroom attendants, where people are required for constant attendance, but the work requirements are intermittent and certainly beyond the control of the worker filling the job.

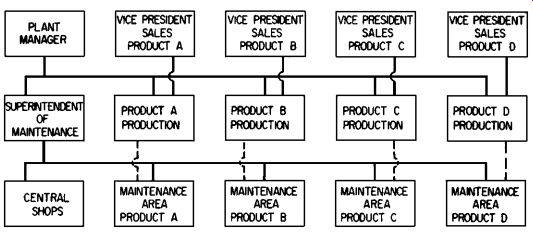

If the majority of maintenance workers are covered by direct maintenance-work measurement, and are receiving incentive pay, some provision must be made to avoid pay-differential problems among assigned maintenance personnel, service personnel, and the scheduled direct maintenance personnel. In some instances, the assigned personnel could be the better craftsmen and yet receive less pay. The same problem exists with service personnel. If other maintenance workers receive incentive bonus, it is necessary to provide a method to increase their earnings with incentive pay.

There have been various plans to measure storeroom work, toolroom work, etc., but because of the intermittent work requirements, none of which is within the control of the service personnel, the most satisfactory arrangement, and purely for the purpose of avoiding pay discrimination, is to pay bonus based on the efficiency of the maintenance workers serviced. The assumption is that the store's attendant will provide prompt service which will avoid dilution of maintenance-worker efficiency through delays that are caused by careless servicing.

The kind of incentive that could be applied to the three work classifications is illustrated as follows:

----------------

Maintenance work classification Kind of incentive plan

1. Direct craft work Plan based on measured standard times. Ratio plan: maintenance dollars to manufacturing-labor dollars, etc. Bonus based on production efficiency

2. Assigned maintenance work

Work load bonus plan. Ratio plan: maintenance dollars to manufacturing labor dollars, etc.

Ratio plan: equipment-operating hours to downtime hours. Bonus based on efficiency of area or group serviced

3. Service personnel Ratio plan: maintenance dollars to manufacturing-labor dollars, etc.

Bonus based on efficiency of area or group serviced.

---------------

The principles and techniques of direct measurement are presented in detail in the remainder of this section. With the exception of the work-load bonus plan, the other types of plans have been discussed under Kinds of Incentive Ordinarily Used.

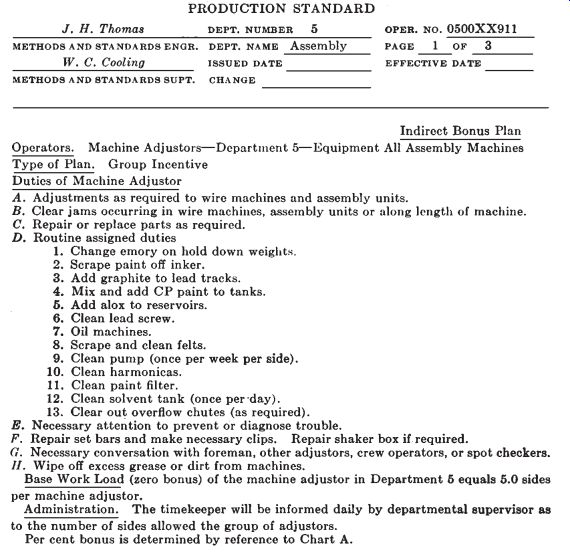

The work of machine adjusters (maintenance-personnel-assigned production units or areas) can be effectively measured on work-load-manning requirements and the net results attained by the mechanics. The following procedure, illustrated by Figs. 1 and 2, has been used effectively to pay incentive for an incentive work load.

Steps in the Development of Work-Load Bonus Standards for Assigned Maintenance Personnel

1. Discuss operation in detail with foreman to:

a. Supply him with background for discussion with union and/or workers involved.

b. Orient the study observer as to plant nomenclature of equipment involved and necessary work duties.

2. Study observer makes preliminary observations to introduce himself to equipment and personnel.

a. Since this type of study does not permit a prepared list of cyclical elements, observer must make mental note of the time-study breakdown of the job into constant and variable elements.

3. Take a series of all-day studies. Number of studies may vary but must include the complete range of probabilities and should be on several different workers if available.

4. Analyze study-elements and occurrences; accumulate times.

5. Discuss (the elements observed) with foreman to avoid possible inclusion of unnecessary work.

6. Determine for each element total time and number of occurrences.

7. Determine time per occurrence for each element.

8. Determine frequency of elements.

Fig. 1

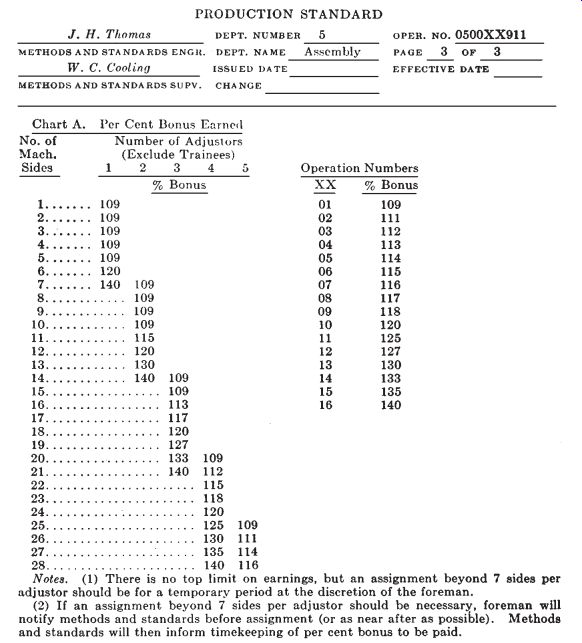

FIGURE 2 The percent bonus is determined from this chart. The term "percent

bonus" conforms to the plant terminology. Actual percent bonus may be

determined by subtracting 100 from bonus figures on the chart.

In the same manner as any evaluation for proposed changes: new equipment, revised methods, lay out changes, as examples. The problem is to determine old costs, without incentives, estimate new costs, with incentives, and arrive at potential savings. Use the approach outlined here for determining maintenance efficiencies. From this determination, a dollar figure can be arrived at, and this savings potential evaluated against the cost of the initial installation and continued administration of an incentive plan.

Forget maintenance ratios, such as the ratio of maintenance labor to production, total plant labor, the ratio of maintenance expense to operating costs or net sales dollar. There are many factors that influence ratios: the trend toward more complicated equipment, the age of equipment, the number of shifts operating, and product mixes. These all have an effect on maintenance costs and will change the ratio. The ratio can rise with a decrease in direct-labor costs while at the same time your maintenance efficiency has not changed, giving a false picture.

The administration of a maintenance plan is about 3 to 12 percent in additional costs. This is a small factor when most companies can reasonably expect a decrease in maintenance costs from 10 to 50 percent. In a survey by Factory Management and Maintenance, covering eight companies of different industries, the additional administrative personnel required for a wage-incentive system amounted to 2.4 to 10 percent of the number of direct workers.

Most of the administrative work required to facilitate wage incentives should be performed as staff services to maintenance foremen whether an incentive system is installed or not. The administrative work required for a wage-incentive program consists of these functions: methods, planning and scheduling, material control, work measurement, and timekeeping. To run an efficient maintenance organization, these functions must be performed with or without wage incentives to maintain proper cost control. Adding incentive pay, in areas where these functions are under control, gives a final push to maintenance productivity.

Low-Cost Administrative Standards for Plant Maintenance. Methods Engineering Council has adopted a unique approach to low-cost administration of plant standards (non-shop work). It is based on their findings that, in plant work, "80 of the total jobs required less than 8 hours to perform." It was also found that, "although these short jobs cause the bulk of standard-setting problems, they rep resent only about 20% of the total time worked in a typical maintenance operation."2 From these facts, it was evident that a method of establishing quick standards on small jobs, to leave the planning and standards groups more time to concentrate on the majority of maintenance hours and material, would reduce administrative hours.

Methods Engineering Council used this approach:

1. A large number of maintenance jobs were studied as they occurred. These jobs were selected to match the types of work that occur in normal day-to-day operations.

2. Jobs requiring about the same amount of working time were grouped (standard work groupings), each group representing a range of time (see TABLE 1).

TABLE 1 Standard Groupings for Maintenance Standards Courtesy of Methods Engineering Council.

This chart is a typical example of how standard groupings for maintenance standards are set up for purpose of administration.

In Cab Cranes (above), Example E-3, it will be noted that to "replace or repair fuse" is under Group A and will take between 20 and 40 man-minutes-but actually 30 man-minutes are allowed. In the next column to the right. Example E-6, it will be noted that this belongs to Standard Grouping B, and that 50 man-minutes are allowed for small repair and adjustment to limit switch-though it may actually take from 40 to 60 min. This, and all above standards will remain constant in the plant where they are set up.

3. The standards applicator determines the standard work grouping and applies the corresponding time to each job.

4. With performance completed on a weekly or biweekly basis, measurement is sufficiently accurate for incentive-wage purposes on this 20 percent portion of maintenance hours.

The above approach is a combination of two methods for applying standards, standard data (80 percent of the hours), and historical data or planner's estimate (20 percent of the hours). This type of application has been termed universal maintenance standards by Methods Engineering Council and does substantially reduce administrative costs. For each incentive installation, it would be necessary to determine the work groupings, then apply standards to various jobs with both methods (standard data and standard work groupings), and determine if the time difference between the two types of standards is acceptable.

Reduction of Administrative Costs. Administrative costs can be reduced after careful study just as labor costs can. When thinking of maintenance wage incentives most people visualize a group of planners working with calculating machines determining work standards. Hand calculation of incentive standards from standard data is obsolete. The use of punched-card data to develop standards removes the hand labor and places data in a more usable form. After standards are placed on punched cards, the cards can be used for a number of administrative aids beyond the payroll function, particularly in planning and scheduling.

1. Before work commences, tab runs with punched-card data coded in various ways will give for any period of time:

a. Standard man-hours required per craft.

b. Standard man-hours required by craft by area.

c. Total standard man-hours required.

2. After the work is completed, for any period of time:

a. Individual worker efficiency.

b. Craft efficiency.

c. Area efficiencies.

d. Job efficiencies.

Punched-Card Procedure for Applying Elemental Standard Data. This system is used at International Resistance Company with indirect jobs that require the development of elemental standard times (see Fig. 3).

Methods and standards:

1. Standard elemental-time tables are developed for all work. Individual elemental times are coded.

2. Standard-data tables sent to tabulating department to prepare pre-punched elemental standard data cards, which include code number and standard time.

FIGURE 3 Punched card procedure for applying elemental standard data.

Tabulating department:

3. A master time-ticket card is punched for each standard time (operation code and standard time).

4. Master time-ticket cards are verified.

5. Master time-ticket cards are sent to reproducing machine where required volume of time-ticket cards are pre-punched for standards applicators.

Standards applicators:

6. Standards applicators receive pre-punched cards along with master time tickets which are used for reordering of cards.

7. Standards applicator develops job standard from print, inspection of work to be done, etc. Pulls corresponding standard-data punched card for each standard-data time. Mark senses number of occurrences of each standard-data time on the time ticket. Prepares a job card which is mark sensed for job number.

8. Applicator places job card on top with standard-data time tickets following. Files job until work is scheduled.

9. Job is scheduled. Applicator pulls job standard (job card and standard-data time tickets), mark senses clock number of workers and work code (incentive or a non-incentive category) on job card.

Applicator keeps time record and at completion of job mark senses actual hours on job card. Standard-data cards are placed on top of the job card and forwarded to tabulating.

Tabulating:

10. Cards are fed to reproducing punch machine which punches out all mark sensed areas. Cards are verified on same machine.

11. Punched standard-data cards are put through reproducing punch machine again which rearranges and punches same information in step 10 on a labor-detail distribution card to facilitate calculation of earned hours and clock hours. Standard-data cards are filed for reference.

12. Labor-detail distribution cards are fed into a calculator which computes earned hours on each trailer card and punches total earned hours on one operation master card.

13. Cards from step 12 are fed into sorter. Obtain two groups of cards: (1) labor-detail distribution cards and (2) master job cards with total earned hours. File labor-detail distribution cards.

14. Master job cards from step 13 are added to other master job cards, fed into sorter, and sorted by clock number in sequence.

15. Cards from step 14 are fed into a collator to match up and merge with a master labor-rate card for each clock number.

16. The merged group of cards from step 15 are fed into reproducing punch machine which punches information from master labor-rate card on operation master cards.

17. Cards from step 16 are fed into sorter to separate master labor-rate cards from operation master cards.

18. Cards from step 17 are fed into sorter again to separate daywork from incentive cards.

19. Incentive cards are fed into calculator which gives total amount spent on lost hours and earned hours and gives a first gross total of lost earned hours. Cards are run through calculator again and checked using different storage units in the machine.

20. Incentive cards are combined again with daywork cards and fed into sorter, sorted by department, clock number, and date.

21. Sorted cards go to accounting; machine transfers punched information from operation master cards to a gross-pay summary card for each clock number. Accounting machine also prints detail-labor efficiency report at this time.

22. Detail-labor efficiency reports are sent to payroll for checking. Corrections are made if required, sent back to tabulation, and gross-pay summary cards corrected.

23. Gross-pay cards are fed into calculator where payroll adds other premiums and overtime if any is calculated and final gross pay punched.

24. Cards are run from step 23 on accounting machine and final gross-pay report is printed.

25. Cards from step 23 are run through reproducing punch machine and transfer punches date, department number, clock number, clock hours, pay hours, tax class, base rate, and gross pay on a net-pay card.

26. Net-pay cards from step 25 are sent to collator which matches cards with master punched cards having deductions by clock number.

27. Collated cards from step 26 are sent to reproducing punch machine and deduction information is punched on net-pay card. Master punched deduction cards are filed.

28. Net-pay cards from step 27 are fed into a calculator which calculates and punches withholding tax, city tax, Social Security assessment. Cards are run through again and checked using different storage units. They are sent through for third time and net-pay information is punched.

29. Net-pay cards from step 28 are matched with master name-file cards and fed into accounting machine, which prints check.

The above procedure looks like a large number of steps. However, the great majority of these steps are machine operations. Another consideration is that steps 9 to 16, with the exception of steps 11 to 13, are a part of the pay procedure and must be performed with or without incentives.

Another part of this handbook describes a procedure for compiling labor and material charges by various classifications to control maintenance costs. The two systems can be integrated for the wage incentive purposes and material--and labor--distribution control and charges.

Preset Standards vs. Postset Standards. With the preset (analyst) method of applying standards, standard times for the work involved are applied before the actual work starts. The postset (checker) method of applying standards refers to the establishment of standard times for the work involved after the work is completed or is in process.

Based solely on administrative costs, the more expensive method of applying standards to maintenance work usually is the preset method. In a chemical plant, a study made of the two methods demonstrated that the preset method was approximately double the cost of the postset method for the same number of craft maintenance hours involved. The cost ratio of craft hours to checker hours (postset) was 1.75 percent and the ratio of craft hours to analyst hours (preset) was 3.60 percent.

3. The above costs should not be taken at face value. There are many intangible savings to be realized through preset standards. Among these items are the planning and control of labor, materials, and equipment. Preset standards force more effective controls. Through the clear definition of work to be done, equipment to be used, and material to be used, costs are effectively controlled. With a postset system, it is possible for most crafts, painters, carpenters, etc., to do more work than is actually required, by less efficient methods, and receive incentive pay, at the same time wasting labor hours and materials. The preset method requires the best management tactics and contributes the most to effective cost control. The last statement has no reflection upon earnings potentials of maintenance workers. It does mean that the money is well spent. The additional cost of preset standards will be more than recovered by tighter management controls.

Amount of Incentive Pay. In the past, there were incentive plans where the employee shared incentive earnings with management. This concept has disappeared with current management thinking and union pressure.

The current thinking is to pay the incentive worker a 1 percent increase in the incentive base wage rate for each 1 percent increase in output. With shop-work where handling methods, machine speeds, and other working conditions make possible a high degree of work standardization, this payment is practical, fair, and easily understood by the employees.

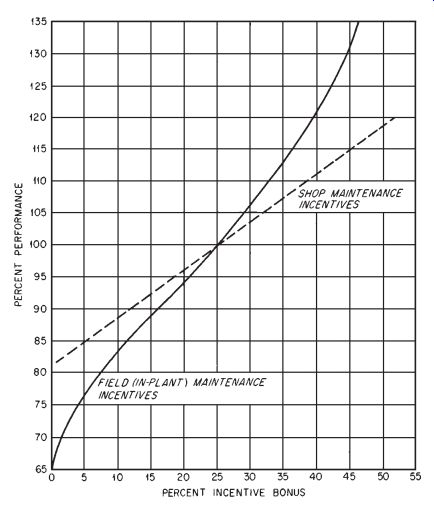

For field (in-plant) work, because of the impossibility of standardizing working conditions as effectively as for shopwork areas, a payment curve is usually established. FIGURE 4 illustrates such a curve. Incentive pay usually starts at a lower level than shopwork and increases at a higher rate.

This is to avoid the abrupt jump from a daywork pace to an incentive pace and encourage the incentive workers to extend their production and earnings. The bonus curve begins to level out between 95 and 105 percent worker-efficiency level. Note that at 100 percent the field incentive worker receives the same bonus as a shopworker. Above the 105 percent level the payments begin to ease off. This curve also attempts to compensate in part for work at the extremes of the averages, the greater than 1 for 1 pay rise from 65 to 95 percent efficiencies compensating for those extremes of the averages unfavorable to the employee, and the easing off of incentive pay above 105 percent to compensate for the extremes in the averages unfavorable to management.

To place a value on the 100 percent operator-performance level, consider this point comparable in worker output to a man walking 3 mph on smooth level ground without carrying a load. With this as a standard, the average shop- and field-efficiency level should equal a payoff of 25 to 30 percent incentive bonus.

Methods of Payment-Group vs. Individual. The various plans which have been outlined can operate with either group or individual payments, which do not concern the basic plan. They are simply methods of distributing incentive earnings.

At a management conference, the following points were advanced as being in favor of group incentive payments:

1. Group payment averages earnings so that each job classification maintains the same pay position.

2. Group payment averages earnings so that each employee in the same craft receives the same incentive pay.

3. Group payment averages difficult work with easy work.

4. Group payment may be extended to cover all hours-even those without standards (nonrated productive work, sweepers, toolroom attendants, etc.).

5. Group payment simplifies the administration of the plan.

FIGURE 4 With the degree of standardization of shopworking areas, a pay

curve providing a 1 percent pay increase for each 1 percent increase in output

is desirable and practical. Field (in-plant) standards, which are based on

work areas that cannot be standardized to the degree of shopwork areas, should

pay on a curve with bonus payments starting at a low level (67 percent), leveling

out in the areas of normal work efficiencies (95 to 100 percent), and tapering

off above that level.

While these advantages of group payment appear to be valid, each one is a compensation for potential errors or inefficient management. With high coverage and good standards, incentive payments between individuals and wage differentials among varied skills should not be a problem. It is only with low coverage and inadequate standards that individual earnings and wage differentials among skills go out of line. With adequate standards as the base for a well-administered wage-incentive system, there is no "difficult" or "easy" work. Most jobs are equitable as long as the basis for the standard data does not change and the standard data are applied correctly to each job. Item 4 above compensates for low coverage and jobs that cannot be placed on standards. As mentioned at the beginning of this section, there are jobs that cannot be placed on incentive with standard data, but a catch-all group plan is not the way to erase pay discrimination caused by the lack of opportunity to earn incentive pay. With item 5, simplified administration, it is implied that basic management controls such as material control and planning and scheduling do not have to be so efficient. Standards and the timekeeping function do not have to be so accurate. If a group plan is installed solely for the purpose of controlling pay scales and allowing for management's faults in establishing and operating basic cost-control measures, the principles of wage-incentive administration have been violated.

The most important advantage of group payment is in promoting teamwork, to maintain a level of quality and to stimulate mutual assistance on jobs. If group-incentive payment is installed with the above in mind rather than the five preceding so-called advantages, together with well-developed control functions and accurate, properly maintained standard data as the basis of the incentive standards, a group plan should achieve about the same results as an individual incentive plan.

The loosely administered group-payment system will be a failure when:

1. Individuals or small groups feel they are "carrying" less efficient fellow workers.

2. Individuals or small groups feel they contributed more incentive earnings to the common "pot" than toolroom attendants, crane operators and helpers, sweepers, etc., who are included in the same plan, and begin to "peg" their production. Poor administration of old standards and careless development of new standards, on the basis that everything will average out, will also destroy the group-payment system.

On a group-incentive basis, group performance would be measured by comparing total standard hours with total actual hours. This does not provide for a job efficiency or individual efficiency or any means to measure individual output for cost-control purposes. If the group includes the workers under more than one supervisor, a group plan does not provide a measure of individual supervisory efficiency.

The following points are advanced in favor of individual incentive payments:

1. Individual incentive can be a basis for the foreman to appraise the production of each employee.

2. Each employee receives pay in direct proportion to what he produces; high producers tend to pro duce more, and low producers have the incentive to improve continually.

3. High producers receive high earnings which are not shared with low producers.

With these qualities, the individual-incentive plan tends to promote a higher individual production level than the group plan.

With maintenance work, where a number of craftsmen work on each job, it is not possible to pay on individual accomplishments. A combination of group and individual measurements must be used.

Each job may be considered a measuring point. The efficiency on each job can be determined by dividing the total standard hours allowed by the actual hours worked. This is group efficiency for the job. The worker's earned hours may be determined by multiplying the number of hours spent on the job by the group job efficiency to determine the total standard hours to be credited to the worker for that job; thus he will share group earnings for that job. However, if he should be in another group on the next job, he receives the same incentive efficiency as each member of that group. At the end of the worker's pay period, his total actual hours from all jobs divided by his total standard hours from all jobs will determine his efficiency for pay purposes. If he should work as an individual during this period, his individual hours would be treated as a job and be included in the total standard hours for pay purposes.

Incentive Pay Periods.

4 The elemental data used for standard-data development are based on nor mal times under normal working conditions. The time studies are made over a lengthy period to obtain these average times under average operating conditions. The allowances that cover unavoidable delays and miscellaneous work are also established over a lengthy period and on average working conditions. Therefore, the incentive pay period must be long enough to be representative of the averages on which the standards are based. A biweekly pay period is normally sufficient to meet these requirements.

There will always be jobs that are not completed by the end of the pay period. A method must be established to pay job base-wage rates for unfinished jobs at the end of the pay period. Incentive payments must be delayed until the job is complete and this portion of total pay can be determined. In some instances, it will be possible to establish incentive-pay breaking points in a lengthy job, so that incentive pay can be paid at a time more closely related to the work.

TABLE 2 Time Allowances Select time, Add delay, Add personal

Lift, ft min misc. 16.8% 5%

20 1.08 1.26 1.32 40 1.60 1.87 1.96 60 2.10 2.45 2.57 80 2.55 2.98 3.13 100 3.00 3.50 3.68 120 3.25 3.80 3.99 140 4.10 4.79 5.03 160 4.90 5.72 6.01 180 6.20 7.24 7.60 200 7.15 8.35 8.77 220 7.95 9.29 9.75

Allowances are added to select times (from figure lift and move in equipment with air tugger) to establish standard time to complete work element. This 5% personal allowance is not totaled with delay and miscellaneous work allowance as these work allowances require 5% personal allowance also.

Allowances. In addition to the select time to perform standard work elements, there are other events in the course of a workday, necessary for successful completion of tasks, that require a time allowance (see TABLE 2). Time must be provided for:

1. Personal needs. Some time must be allowed to provide for necessary events such as visiting the washroom, adjusting clothing, and other personal needs. This is not a measured allowance, but a negotiated or agreed allowance depending on the type of product, nature of work, etc. This allowance varies from 2.5 to 15 percent of total standard time in current practice, with the majority of incentive plans using 5 percent.

2. Delays and miscellaneous work. With maintenance work, there are certain delays that may be minimized, but not avoided. There will be a lower percentage delay time allowed in shopwork than in plant work. Shopwork areas are planned and arranged to reduce delays and miscellaneous work. This is not always practical for field (in-plant maintenance work). Time must be provided for these unavoidable delays.

a. Miscellaneous work. In most jobs, there exist some nonrepetitive or irregularly occurring items which must be performed in connection with the regular job. These items are usually different in character and not of sufficient duration to justify their coverage by individual standards. Such jobs as removing equipment obstacles and adjusting and sharpening tools fall into this category.

b. Interference. Inherent factors are to be found in every job which interfere with the normal flow of work, such as waiting for other crafts and delays due to cranes, trucks, etc., that are on other jobs.

c. Crew balance. In some classes of work, where more labor within a craft is needed on some portions of a job than can effectively be used on the entire job, a condition of enforced idle time exists. An example might be riggers waiting for a tugger load to be raised into position.

Where crew size can be scheduled for positions of a job, this allowance is not required.

d. Abnormal work. Direct or supplementary work that is encountered at the time of the study which cannot be considered as a normal function in the completion of the job. An example of this would be the fitting of safety boots on a high power line by the riggers while hanging a boilermaker's chair near the line.

These allowances may be determined through a series of 8-hr time studies or through the ratio-delay procedure. The computation of these allowances is illustrated by TABLE 3. In some instances, the allowance would be applied only to specific categories of work. With riggers using a tugger hoist (Fig. 5) there is a higher crew balance time necessary than with other classes of rigging work, because of alternate waiting time by the hoist operator and helpers while loads are being raised. A specific crew balance allowance could be determined and applied only to this particular class of rigging work.

TABLE 3 Computation of Allowances for Rigging

FIGURE 5 Select times for one element-lifting and moving equipment with air tugger. Line is drawn through average of time-study data to represent selected standard times. Allowances must be added to these select times to obtain elemental standard-time data.

3. Machine allowance. This allowance usually enters the picture in shopwork where an operation is machine-controlled and an operator cannot earn incentive pay with extended effort. In order to avoid discrimination and inequities in pay, it is a practice in many shops to allow an incentive factor on the machine elements of the job. Where it is possible to schedule work during machine time or utilize operator time during machine periods by adding other machines, this allowance can be avoided. If it is not possible to find a useful activity during machine time, this type of allowance should be considered to enable an operator to earn incentive pay that will approximate the earnings of the other people in the shop. The allowance might be applied in this manner: 5 percent machine allowance for jobs that are under 50 percent machine-controlled and 15 percent machine allowance for jobs over 50 percent machine-controlled. The potential pay of non-machine operators will have to be considered in each individual case in establishing machine allowances. This is not a time-studied allowance and must be used only when there is a true need.

4. Specific conditions. Examples will follow to outline the need for this allowance but each plant has specific problems and must determine its own allowance based on the individual need.

Working inside a closed vessel, such as a tank, requires an allowance for conditions such as inadequate ventilation and restricted movements in the working area. Work areas with extreme temperature conditions, hot or cold, would require this type of allowance. It can be determined only by job experience, past working practices, or agreement. Allowances for specific conditions that run as high as 50 percent are not unusual. An allowance of this type is not built into the elemental time standards but is applied to those portions of the job standard where the need arises.

5. Job allowances. Preparation and cleanup allowances must be developed and applied on a job basis since it is impossible to prorate this time in the elemental standard data with the number of jobs varying from day to day. There are also specific job allowances that can be encountered. For example, in a plant processing selenium rectifier plates, exposure to this type of metal requires frequent washing of hands to avoid swallowing the selenium particles. Maintenance work in this area requires an allowance, beyond that of the normal personal allowance, to provide for cleanup time. This allowance would not be included in the standard times but would be issued as a time value in the form of a job allowance for work in that specific area.

In the process of developing standards, avoid placing any allowance in the elemental standards for conditions that are not present in the average 8-hr day. For example, use job allowances for such items as clocking in and out, job preparation, and cleanup. This time will then be charged to the specific jobs where the time was required. Use a daily allowance for instruction and preparation time at the start of the day and cleanup at the end of the day, if these items are completed on company time.

For cost purposes, the daily allowance (nonproductive) can be charged to maintenance overhead for proper prorating to individual jobs.

When Adopting Incentives, Recognize These Facts

1. The same controls are needed for efficient cost administration with or without wage incentives.

A wage-incentive program will not be a success without successful administrative controls.

2. A wage-incentive program requires a higher degree of management administrative skill than a daywork program. A wage-incentive system does not control costs, the people who run the sys tem do. Therefore, management control functions, such as planning and scheduling, and cost accounting must be functioning at a high efficiency level. All a wage-incentive system can accomplish is to pay a worker more for supervising himself as to (1) work time and (2) the skill and effort that he applies to his job.

3. Supervision and the workers play major roles in a successful wage-incentive plan. Both super vision and representatives of the employees should have an appreciation course in methods and time study and a training course in the administration of wage-incentive standards and policies.

All employees should have a general idea of how standards are set, how they are administered, incentive-pay policies, and how to compute their pay.

4. Every phase of management will be affected by a wage-incentive program: engineering, production, industrial relations, and accounting. All these functions must be oriented with respect to their responsibilities and contributions.

5. A wage-incentive policy is necessary with or without a union. Individual practices or interdepartmental practices should not establish policies.

6. An incentive program must be established only when a firm base-wage-rate standard exists.

7. Extreme care and study must be used in the selection of an incentive-payment plan. More than one payment plan may be instituted to take care of specific work circumstances (i.e., shop or field). Each plan must be tailored to the type of work that is to be measured.

8. Plan a payment curve that avoids an abrupt jump from a daywork pace to an incentive pace.

Tailor payment curves to the degree of reproducibility of working conditions.

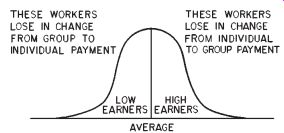

9. The choice of payment (group vs. individual) under the incentive plan must be final. FIGURE 6 shows an efficiency distribution of a group of workers. In changing the payment method from group to individual, the worker performing at below-average efficiency would take a pay cut.

Should the change be the reverse, from individual to group, the workers performing at the above-average level would receive a decrease in earnings. It is obvious that such a change in the method of incentive payment will leave about half the workers dissatisfied and would not be acceptable.

10. If an incentive plan is to reach the maximum point of effectiveness, the basis for incentive earnings must be directly related to the output of skill and effort of the workers. A ratio plan that can be influenced by factors beyond the control of the workers can be more difficult to administer successfully than a direct measurement plan.

FIGURE 6 Efficiency distribution of a group of workers.

When Adopting Incentives, Don't

1. Install incentives where management is not wholeheartedly behind the program.

2. Allow the imagination of supervision or the workers to run loose with any phase or problem of the incentive system. (Pay is involved; keep them informed.)

3. Under-hire. (Pay for capable industrial engineering personnel.) As for supervision, don't keep any supervisor unless he can be trained in wage-incentive administration and is willing to accept his new responsibilities. (If personnel are selected from within to function as industrial engineers, supervisors, or timekeepers, make sure they are formally trained. This can't be done overnight.)

4. Place industrial engineering in the role of time study and rate setting. (The standardization of working area, working conditions, and working methods requires competent personnel operating above the level of time study and rate setting.)

5. Install an incentive plan without prior consideration of what to do with excess working hours that are going to be available. (A consideration of work load and number of people involved is most important.)

6. Install a piece rate or any dollar system. (In an era of wage increases, the maintenance of this type of standard is impractical. A standard-hour system requires no change in incentive standards, when an increase occurs. The only changes required occur in the accounting function.)

7. Adjust standards, through increased bonus allowances, to give pay increases. (Provide for pay increases in the base wage rates.)

8. Attempt to eliminate pay inequities through incentive payments.

When Developing Incentive Standards

1. Standardize work methods. It is not always essential to install the best method if this will require a long period of time. When work is standardized, it may be studied, the standards issued, with the employee earning incentive pay and management enjoying lower costs. Delay while waiting for a new method to be approved and installed will result in lost pay to the employee and lost efficiency to management. The new method may be installed at a later date after it has been perfected and approved by management and any additional equipment procured. An incentive system must provide the opportunity for incentive earnings to satisfy the incentive workers. Don't hold up incentive standards.

2. Study standard work methods and train workers in them.

3. Make some provision for machine-paced operators to earn incentive pay. Attempt to provide work for operators during machine running time or plan for multiple machine operations. If these are not possible, it may be necessary to add an allowance for machine running time to avoid incentive-pay discrimination.

4. Keep the workers involved informed of the progress in developing standards.

5. Review in detail the results of time studies and the buildup of standard data with supervision and employees' representative.

6. Use sound industrial engineering techniques to develop a standard; workers' pay is involved.

7. Train supervision in the method of introducing a standard to the workers. This is a major part of the supervisory administrative function.

8. Standard data must be based on a large number of elemental times for each work element to obtain a select time that will be representative of average working conditions.

9. Include allowances to cover delays and miscellaneous work that are unavoidable in maintenance work.

When Developing Incentive Standards, Don't

1. Study an untrained worker and attempt to adjust for lack of training by leveling.

2. Study an operator using a poor method and attempt to adjust by leveling. (Have the foreman instruct the operator in the proper method; then study.)

3. Study a job under conditions other than those normally experienced.

4. Study an operator who is not giving an honest performance. (Inform supervision when this condition occurs for correction.)

5. Pay a supervisor bonus based on the working efficiency of his people. (When his pay is based on working efficiency alone, there is a conflict of interests, which usually results in poor wage-incentive administration by the foreman. This practice can encourage supervision to make methods changes without calling for adjusted standards, create improper timekeeping practices, and in general result in the failure of supervision to give management leadership to the job of wage incentive administration.)

6. Use temporary standards. (A short-term standard should be established on reproducible conditions, and the term temporary avoided. A new standard can replace the short-term standard when a change is made that affects time.) Administration of Wage Incentives Calls for

1. An aggressive but fair approach to all problems regarding them. Treat every wage-incentive problem as a major problem because pay is involved. Immediate action is necessary on every question or complaint; retroactive pay might be involved to complicate the issue further.

Publicize the fact that action is taking place and keep the workers informed as to progress.

2. A procedure to handle all questions concerning wage incentives, with or without a union.

3. Making all data available to anyone who has questions concerning the development of incentive standards.

4. Constant review of incentive payments, searching for possible wage inequities. Be constantly aware of the amount of incentive coverage. Keep coverage high so that incentive payments can be maintained through productivity and not guarantees.

5. Establishing a long enough pay period to cover average working conditions (biweekly).

6. Guaranteeing incentive standards against changes. When change is made because of a methods change or any other change that adds or removes work from the job, take the necessary time to review with the workers involved that change and its effect on time. Review comparisons of the old and new elemental times and the development of the standard. Supervision should be the leader in this presentation to the workers.

7. Accepting the maintenance of existing standards as the primary function of the standards department. Accept this as a necessary cost to manage an effective wage-incentive system. Immediate action is necessary when a change of work methods occurs to continue the earnings opportunities of the workers involved. It is a problem to effect a smooth methods change. Loss of incentive pay after the new method is installed will further complicate the problem.

8. Paying bonus only on the method used to complete tasks.

9. A high degree of standards control by rate setters or applicators who are highly skilled individuals in craft-work methods, use of standard data, and timekeeping procedures.

10. The availability of complete, accurate data to substantiate existing standards and compare the effect of old vs. new methods.

When Administering Wage Incentives, Don't

1. Establish a ceiling on wage-incentive earnings.

2. Neglect to judge the quality of in-process or finished work. (Incentive standards are based on the necessary time for a normal operator to complete acceptable work. Supervision must accept the responsibility for obtaining acceptable work.)

3. Apply standards to any job unless working conditions, material, equipment, and work methods are standard.

4. Allow delay in the settlement of grievances. (Every problem, large or small, must be settled within the shortest possible time.)

5. Bargain incentive standards. (Confine bargaining to base wage rates.)

6. Allow lengthy jobs to exceed pay periods. (Whenever possible on large jobs, attempt to establish breaking points to pay incentive wages as close to the actual work date as possible.)

7. Allow the evaluation of the effect of any change of work methods to be made by anyone outside the standards department. (No matter how large or how small the change may be, it is a supervisory responsibility to report this change for proper evaluation.)

8. Allow money to replace worker satisfaction in his contribution to completed jobs. (Management must be capable of creating and continuing high worker morale for individual and group accomplishments.)

9. Allow industrial engineers to deal directly with workers or their representatives regarding wage incentive problems. (This is transferring the leadership of wage-incentive administration from supervision to a staff function. Supervision always requires competent assistance in administration of wage incentives, but only as a staff function.)

10. Use methods changes as an attempt to correct out-of-control standards. (An incentive worker should have the same incentive earnings potential with the application of the same amount of skill and effort under the old and new standards. Loose standards must be adjusted by the collective-bargaining process. Failure to comply with this principle will jeopardize the acceptance of methods changes. This acceptance of methods changes and new standards is far more important than picking up a few cents here and there under the subterfuge of a methods change.)

PREV | NEXT | Article Index | HOME