AMAZON multi-meters discounts AMAZON oscilloscope discounts

GENERAL

Considerable confusion has developed in the discussion of area and central maintenance control, mainly because a clear definition of the items being dispersed or centralized has not been made. The two most critical items in this discussion are geography and organization.

Geography. The distribution of men, tools, material, etc., to positions within the plant site, geo graphically central meaning all men, tools, and material located at one point Organization. The direct organization control of craftsmen, including their supervision, scheduling, and guidance, organizationally central meaning the control of all maintenance in the facility by one person below the level of site manager

It is also important to remind the reader that no plant need be established all area, all central, etc., but instead each should utilize the advantages of each possibility to fit the particular needs of the specific plant. Based on this, it is conceivable that owing to geography, plant age, etc., various plants making the same product within the same basic organization could be structured in quite different manners.

As a result, there is no proper way to recommend a specific format for any plant or situation.

Instead, certain concepts will be discussed and several actual examples presented along with some of the advantages and disadvantages of each. Each plant must thus utilize this information to make the specific decisions for its specific situation.

It is generally true that if a maintenance structure is geographically centralized, it will be organizationally centralized, although theoretically it need not be. On the other hand, a maintenance structure which is geographically area-oriented can be controlled either centrally or by area depending on many factors described in this section.

There is a universal desire of every production manager to have his maintenance available when he needs it. The cost of downtime is often inflated to the point where justification for organizational and geographic area maintenance is quite obvious. If there were no cost penalties for area concepts, this would not be bad, but unfortunately there is often an increased cost in area concepts due to duplication of tools, idle crafts, unbalanced backlog and work loads, etc. It is important that the over all balance be reviewed and real cost penalties and/or advantages be evaluated.

ITEMS TO BE CONSIDERED

The following list presents (in no special order) some of the items which must be considered in each plant in determining the degree to which central and/or area maintenance is to be utilized.

Plant Size. Very large plants which require vehicular transportation to reach various locations often result in geographical-area maintenance to allow overall efficiency. Plant size, however, is not necessarily the predominant factor in the decision as to whether or not to have organizational-area maintenance.

Number of Buildings, Floors, Etc. Manufacturing facilities which, although small by comparison, have many buildings or floors may lend themselves to geographical-area control; however, as with plant size, not necessarily organizationally.

Shop-Space Allocation. Shop-space allocation may force geographical centralization or area control. For example, a plant with no large space available but several small areas separated and set aside for maintenance may dictate a geographical-area concept. Other plants may have but one large area and no "out areas" and thus require geographical centralization.

Area Skill Requirements. When the maintenance skills necessary for one area of a plant are special and specific, they may necessitate not only a geographical but also organizational area concept.

In some instances the maintenance forces may be virtually technicians and central control may be impractical.

Area Tool Requirement. When the maintenance tools for a specific area are very special, this often necessitates a geographical-area concept. Such is the case when one portion of a plant is explosion proof and the tools must be separated for special safety.

Size of Maintenance Force. The overall size of the maintenance force has a definite bearing on decisions. When the maintenance force is very small, it is usually impractical to use area concepts, either geographically or organizationally. The definition of "small" as used above is difficult, since other factors mentioned in this section come into play, but in general, 15 or fewer craftsmen would be considered small for this purpose.

Size and Distribution of Crafts. When the needs for various crafts are somewhat equal, and the number of each craft in a production area is small, a geographical-area-oriented maintenance situation is often utilized. For example:

Area I Area II Area III

4 Craft A 2 Craft A 2 Craft A 2 Craft B 4 Craft B 2 Craft B 2 Craft C 4 Craft C 3 Craft C 3 Craft D 0 Craft D 3 Craft D 0 Craft E 2 Craft E 4 Craft E

Skill Orientation of Supervision. In the aforementioned craft distribution, an obvious requisite is that the geographical-area foreman have the skill to supervise various assigned crafts. This does not necessarily mean he must be expertly skilled, but he must be capable of supervising. Because of the special supervisory skills required for certain crafts (electronics, some welding, etc.), in some cases a combined central and area would be used for the aforementioned:

Number of Maintenance Supervisors. In certain plants, the number and location of craftsmen are such that there is an uneven demand for maintenance supervision. A typical example is the maintenance force of 17 men of several crafts, which may be more than one supervisor can properly handle, yet not sufficient for a second supervisor. This may be handled by using an organizational-area concept:

Maintenance supervisor service area I and II

Service to area III 4 Craft A 1 Craft A Report to Area III 4 Craft B 1 Craft B production 6 Craft C 1 Craft C supervisor

Area I and Area III and part of II part of II Crafts D and E

5 Craft A 2 Craft A 6 Craft D 2 Craft B 6 Craft B 6 Craft E 4 Craft C 5 Craft C

Note: This is a typical example of a combination of geographical area and organizationally central maintenance as referred to at the beginning of this section.

Corporate Organizational Concept. Some corporate structures are divided by product line or ser vice, to the point where each is an autonomous group. When various groups are serviced within one site, it is often essential to have organizational-area control. This does not necessitate geographical area control, but it does create certain special problems for a maintenance organization.

Cost of Downtime. When the real cost of downtime is so great that it overshadows the possible added cost of organizational and geographical area maintenance, the area concept should be utilized.

(Note: It is often possible to become carried away with the desire to reduce maintenance costs and in the process fail to remember that the reason for maintenance is to aid in the production of an economically sound product. Although area maintenance may be more costly from a purely maintenance standpoint, the cost of downtime can often overshadow other factors.)

EXAMPLES

As stated earlier, there are numerous combinations of area- and centralized-maintenance concepts.

Following are several examples from the author's experiences. These examples are provided to expand further the possibilities to be considered by any plant in its decision-making process.

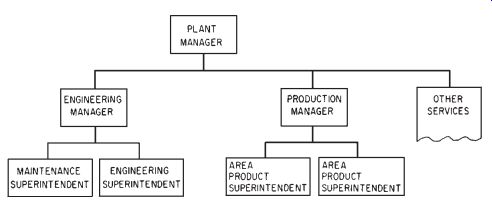

Plant 1. A process plant covering several square miles, over 10 basic and somewhat independent product lines, and about 300 maintenance employees. The maintenance organization was central, as shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1

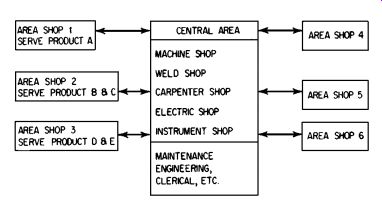

In this plant, all maintenance was under the control of the maintenance superintendent; however, a portion of the services was geographically spread out to service the producing units, as shown in Fig. 2.

Each of these area shops was staffed with at least one maintenance foreman plus an appropriate number of craftsmen such as pipefitters, welders, carpenters, field machinists, and electricians. The area shop was physically sized and tooled to do routine repairs for the specific area; however, larger or more complex jobs were sent to the central area for action.

This arrangement provided good service to the areas through craftsmen and supervisors who were familiar with the particular area units. Travel time to jobs was minimal, and frequently used parts or subunits were available with little or no transportation problems. Esprit de corps was excellent in the various areas, sometimes to the point where it was difficult to maintain the central organization lines in maintenance and not slip to an area-oriented organization. There was a tendency to maintain a given number of craftsmen in the areas to meet emergencies; however, it was difficult to maintain the productivity levels of the crafts. Often area craftsmen were idle or were doing work in the area shop which could be much more efficiently done in the central shop. Because of the multi-skill requirements of the area foremen, it was sometimes difficult to find and/or train men to handle the various groups.

A well-run maintenance planning and scheduling function can be an excellent aid to such organizations, since they can distribute work, span peak periods, and generally improve the efficiency of the various areas. They also serve as the nerve center to utilize the central functions in serving the various areas. Once the area groups (both production and maintenance) develop faith and understanding of a planning function, the overall efficiency can be improved and many of the disadvantages of an area concept can be minimized. Crew sizes within the areas can be minimized as long as the areas are convinced they will receive adequate aid when jobs beyond their capabilities come up.

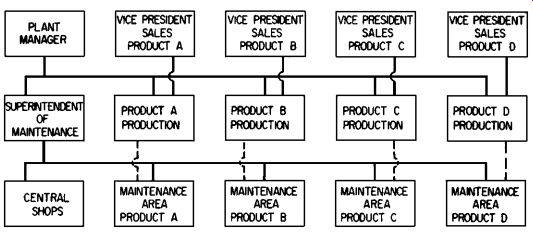

Plant 2. A process plant covering several square miles, four basic and independent product lines, and about 300 maintenance employees. The product oriented organization resulted in area maintenance organization with a central maintenance facility for direction and central service. The plant organization is shown in Fig. 3.

FIGURE 2. Plant 1: The relation of the central area to the area shops.

It is not the purpose of this section to evaluate the general organization shown in Fig. 3, but it is obvious that such an organization provides a tremendous tie between the various product vice presidents and their appropriate producing units. At the same time, the maintenance organization problems can become critical if not properly organized.

This plant utilized facilities similar to those of the plant described earlier (Plant 1); however, the product area maintenance supervisor has much more control over the activities within his area. The distribution of floating crews or central shop services was determined by the maintenance superintendent, but he received his priority guidance from the plant manager as expressed by the product vice-presidents.

The key to this organization was the priority-determination system. Maintenance priorities are difficult at best, but the response by a plant organization to several external company officers is an added burden. It can be done, once again with a strong central maintenance-planning staff and a corporate-accepted priority concept. The most complete and objective fundamental priority concept is RIME (relative importance of maintenance expenditure) as presented by E. T. Newbrough in "Effective Maintenance Management" (McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York).

Plant 3. A manufacturing plant covering several multilevel buildings with over 1,000,000 sq ft of floor space, and about 60 maintenance employees. Because of contractual limitations, the maintenance employees were very craft-oriented into many small groups, as shown in Fig. 4.

FIGURE 3 Plant 2: Plant organization.

FIGURE 4 Plant 3: Craft orientation in maintenance.

The multilevel, multi-building plant facility and the limited availability of elevators made the response time from the central maintenance facility quite long. Several attempts had been made to utilize the area concepts; however, on each attempt several problems repeatedly came up. To staff each area location with the essential crafts required a force increase of about 20 percent. Even with such an increase, supervisory control became difficult from central; thus there was the request for added supervision. Attempts to utilize the production supervisors as maintenance foremen proved to be more of a problem than a solution.

This particular plant found the most efficient and economical maintenance to be a central organization with a central facility; however, each building area was equipped with a small work area and maintenance supply facility under the control of maintenance. There were obvious times when production delays were directly attributable to maintenance forces not being immediately available, but their overall impact was less than the cost of an increased firehouse maintenance concept.

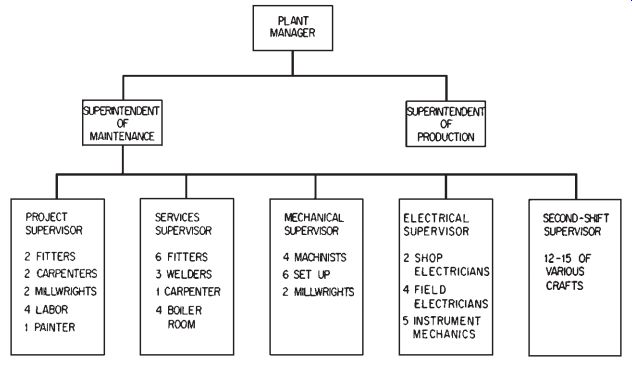

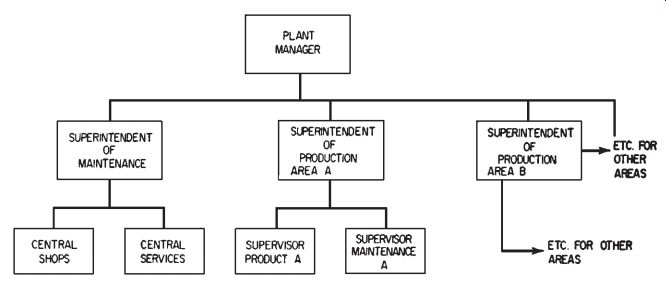

Plant 4. A manufacturing facility covering several square miles, one basic product with four distinct final product configurations, multi-building, large equipment, and about 2000 maintenance employees. The maintenance organization was shown in Fig. 5.

FIG. 1

FIGURE 5 Plant 4: Maintenance organization.

Because of the size of the maintenance force in this plant, plus the need for high equipment utilization, the maintenance was organized on an area basis geographically and organizationally. There was a dotted-line responsibility between the superintendent of maintenance and the area supervisors of maintenance to provide technical and administrative guidance to the areas.

The assigned area had sufficient staffing to respond to most of the area needs with the exception of large repair shops such as machine shops, motor repair, and construction. Because of the size and multi-shift operation, the area was to a great extent self-sufficient.

In large heavy-machinery plants where equipment utilization is the economic lifeline, such area concepts are common and have obvious advantages. Their ability to respond to the production needs is excellent, and with a direct organizational tie to the production unit there is excellent communication with respect to priorities, goals, etc. There is usually an excellent relationship between the operating and assigned maintenance group, since they have the same immediate supervisor. An added advantage is that the operating superintendent is not only financially responsible for the entire area (including maintenance) but physically responsible.

The key to this system is the area supervisor of maintenance. The particular area tends to become a reflection of this man, and his strengths and weaknesses become a distinct part of the maintenance program. Because of his isolation from an outside evaluation, many times these weaknesses can cause serious problems in a given area. The dotted-line relationship between this area man and the superintendent of maintenance is designed to reduce this individual impact, but it requires continued management guidance to ensure that this takes place.

PREV | NEXT | Article Index | HOME