In contrast to summer gardens, a winter garden is mostly savored from indoors, looking out. “Let’s face it,” says one realistic gardener, “how many of us will tramp across the yard through a foot of snow to inspect our Christmas roses?” So in designing your winter garden, begin from the vantage point of a room with a view.

Where, in the winter, do you sit most often and look out? The answer may surprise you. Quite often it’s not in the living room, which may face the street rather than the garden. For one family it’s an upstairs sitting room. For another it may be the kitchen, the family room or a bedroom.

In fact, you may discover that you spend more time at a window in winter than you thought you did. True, the days are shorter and darkness comes early, but the view in winter is often clearer than in summer. The leaves are off the trees, the light is frequently brighter, and you may even see the horizon. “There’s all that sky,” says one gardener, “plus the neighborhood vistas that open up. And the bird-watching is particularly good — in summer we lose sight of most of their comings and goings.”

Your winter garden, then, will be part of this scene. But how you choose to introduce and develop it depends on several variables. You could, for example, create a design for a winter garden that extends throughout your property, or you might decide to confine the garden to a separate area that is visible from a single window. If your land is flat, you might extend the winter garden to your property line. If, on the other hand, the ground slopes away, you might prefer to end your garden a few feet beyond the window.

Refreshed by a granular crusting of late winter snow, the perky berries and bronze stained leaves of a patch of wintergreen ground cover enliven a garden in the Pacific Northwest with eye-catching color.

However you resolve such questions of design, your winter garden should blend harmoniously into the landscape throughout the year, but at the same time should emphasize plants that are particularly beautiful in the winter. There are an astonishing number of choices. Among them are trees and shrubs with unusual shapes or with foliage that turns surprising colors. Other qualities that contribute to what is sometimes called “winter interest” are colorful stems, buds or trunks, bark that peels or flakes attractively, handsome berries or decorative seed pods.

By the same token the winter garden should exclude from view those plants that are far from their best at this season. Forsythia, for example, is a glorious sight in spring but rather nondescript in winter. Some gardeners give rhododendrons poor marks in winter because their leaves roll up like cigars when temperatures drop below freezing. For one gardener, however, the rhododendron’s leaves are an indispensable feature of his winter landscape. “All I have to do is look out the window at my rhododendrons to see what the temperature is,” he says.

SILHOUETTES AND SHADOWS

Bear in mind, too, that the winter garden presents a different set of visual relationships. In place of the dominant greens of summer, there are now light browns and grays; against these softer hues, bits of color stand out that in summer would be lost. Variations in the texture and color of evergreen foliage are more noticeable. Because the angle of the sun is low, silhouettes and shadows take on strange shapes; shining through foliage or bare branches, the slanting rays of the sun create interesting patterns on the ground or on snow. In fact, snow itself provides a succession of different effects as it progresses from soft powder to a more solid blanket and finally through a gamut of melting stages.

But while subtle colors and textures can be endlessly intriguing, the winter garden’s primary visual impact comes from the forms of its plants, chief among them solid masses of tall needled evergreens. These plants are an example of what landscape architects call “bare bones” — elements such as walkways, fences, tall trees or hedges that define the garden’s structure. If the basic plan of your garden is agreeable, plants appear at their best. This is true throughout the year, of course, but it’s particularly true in the winter. As one designer put it, “ You can get away with an awkward garden in the summer, when there are flowers that distract the eye, but not in winter when the camouflage is gone.”

ARRANGING THE BARE

The best-designed gardens are generally based on very practical considerations. First, make a sketch of the area to be developed for your year-round garden, outlining planting areas, walkways, terraces and fence lines as they seem most pleasing to you. Make sure that the planting areas are large enough to accommodate a number of plants and that you have allowed enough room for the movement of people. Sometimes a minor alteration in the shape or placement of a terrace or walk will greatly enhance a garden’s usefulness or balance. Then take a closer look at your plan with winter in mind. One thing you will want to consider is how much sunlight the various parts of your garden receive at different times of the day. Winter-flowering plants such as the Christmas rose require shade in the morning so that their flower buds will thaw gradually after the night’s freeze; broad-leaved evergreens will benefit from the partial shade cast by a bare deciduous tree, since direct sunshine may cause winterkill.

SHIELDS AGAINST THE WIND

Fences, walls and hedges are also important considerations because they shield the garden from wintry winds. But they perform this function in different ways. When wind hits the solid barrier of a panel fence or wall, it’s momentarily deflected upward but soon continues with unabated force on the other side. Only the narrow area immediately against the barrier’s leeward side is protected. But when wind hits a hedge, its force is broken into swirls and eddies and does not rebuild for some distance. A hedge therefore protects a much wider garden area on its lee side.

The type of hedge you choose depends partly on esthetics: it should suit the garden’s scale. But if privacy is a consideration, or if you are screening out an unappealing view, an evergreen hedge is an obvious choice. In winter, a deciduous hedge loses much of its effectiveness. Furthermore, a needled evergreen will generally screen more effectively than a broad-leaved evergreen because its foliage is denser. But a row of needled evergreens along the south side of your garden will cut off much of the winter sunlight.

MAKING THE MOST OF SNOW

Give special attention to the contours of the ground. Variations in ground level can be appealing in winter snow. The patterns made by melting or windblown snow on a rolling lawn can be quite beautiful, and some homeowners deliberately grade their lawns to accentuate this effect. Snow sometimes creates odd shapes atop walls and fences. With this in mind, you might want to finish the top of a fence with narrow horizontal strips, to catch snow in ribbons that look like decorative icing on a cake.

A number of other elements in the bare bones of a garden’s composition deserve special consideration. Trellises should be intrinsically good-looking; in winter, with no greenery to hide them, their design is revealed. Statuary makes the transition into the winter scene easily — provided it’s weatherproof. Rocks can be strong focal points in a winter garden. If nature has not supplied them and you are adding some, be sure to set them solidly into the ground with the grain of all the stones running in the same direction.

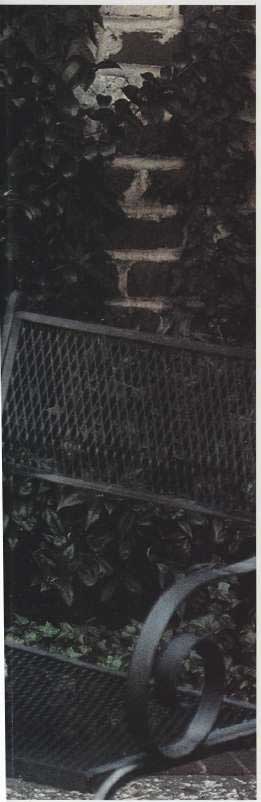

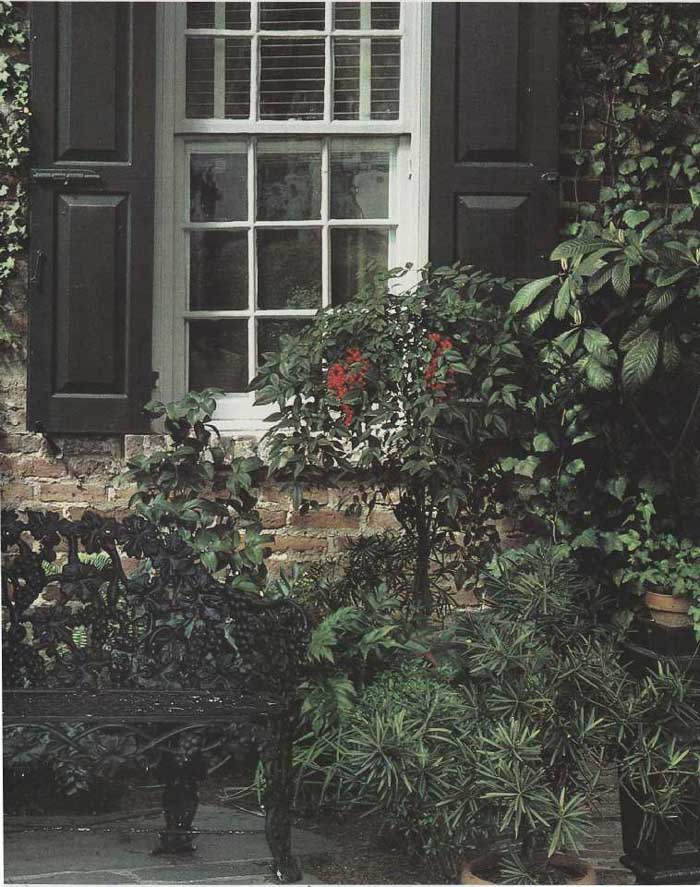

Finally, the sight of chairs and tables in a winter garden can, rather surprisingly, be very appealing. The most practical furniture for this purpose is rustproof wrought iron or plastic-coated metal because these materials dry quickly and are easy to maintain. But rot-resistant wood, although slow to dry after a snowfall, tends to appear warmer and more inviting and blends naturally into the colors of the winter landscape.

A MIXTURE OF PLANTS

With the garden’s bare bones determined, you can turn to refining your selection of plant materials. An important question to be resolved is the mix of evergreen and deciduous plants. Some gardeners believe that the more evergreens they have, the better. Evergreens, it’s true, are the mainstays of the winter garden, flourishing when everything else around them appears to be dead. But their solid mass can be monotonous and can make the garden seem dark — the very opposite of the effect you want on a gray day in winter. Mixing evergreens with deciduous plants lets in light and air and may introduce such provocative extras as colorful stems, attractive bark or interestingly formed branches. Some of the best winter effects are achieved by placing lacy deciduous shrubs against a banked group of evergreens or, reversing the order, by placing evergreen shrubs where they will be seen against the delicate tracery of deciduous tree branches.

Fully as important as the mix of plants is plant hardiness.

Although you may want to include a plant or two that is marginally hardy in your area, it’s best to compose the basic framework of your garden with plants that are absolutely reliable. Otherwise, if you have a severe winter the entire garden may be wiped out. The hardiness range of many plants to consider for winter interest is given in the encyclopedia entries in Section 5. Even if a plant is cleared for the zone you live in, it’s advisable to check with a knowledgeable local nurseryman or an extension agent before buying; your particular neighborhood may be exceptional.

- - - -

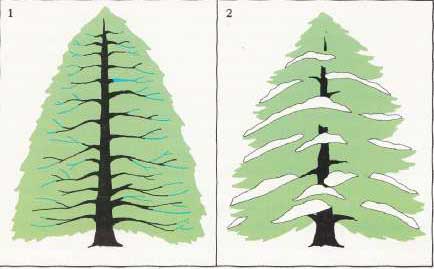

SHAPING UP SHAGGY CONIFERS

1. Conifers such as spruce, fir and pine may conceal an attractive framework beneath shaggy foliage. To expose a shapely trunk-and-branch pattern, thin out branches (blue) in late spring or early summer, cutting them back to the trunk with lopping shears.

2. Careful pruning improves the appearance of these evergreens, especially in winter when they are set off by a light frosting of snow. Pruning also lets more sunlight and air reach the tree’s center, producing healthier foliage near the trunk.

- - - -

EVERGREENS UNDER WRAPS

In considering hardiness, you will want to decide early how you feel about wrapping plants with burlap during severe winters. Landscape designers usually are against it. “I don’t believe in putting my plants in shrouds,” says one. “A plant has to make it on its own and it’s odd, to say the least, to hide the green that makes it evergreen.” To which one winter gardener on the New England coast replies with some asperity, “That’s all very well, but if we had not wrapped our evergreens during one recent winter, we would have lost them all.” In the end, to wrap or not to wrap is something you must decide for yourself, based on conditions in your own garden.

In choosing trees for a winter garden, the possibilities are many. Some can be singled out for grace and elegance of form. There are, for example, the dogwoods and Japanese maples, both notable at other times of year for their foliage, flowers or berries; both have, in addition, a handsome framework of branches that makes them outstanding in winter gardens. The beeches are also splendid in winter, having a special grandeur, but they grow very large. More manageable is the European hornbeam, which has a distinctive oval shape.

FORMS OF DISTINCTION

There are a number of needled evergreens that also have shapes of distinction. You might want to consider, for example, some of the cedars or firs, which are best suited to large gardens since they may become extremely tall. In the eastern United States, the broad pyramidal shape of the white pine makes it a good choice, while Western gardeners might select the picturesque, spreading bristle- cone pine for their winter settings. For gardens near the sea, the angular asymmetrical Japanese black pine resists damage from both high winds and salt spray.

For even more distinctive shapes, there are weeping and pendulous trees. The weeping hemlock, some of the cherries and the Red Jade crab apple are good examples; the bright red fruit of the latter may also last into the winter. The white trunk of the European birch, obscured by its drooping branches in summer, is visible in winter. A classic, of course, is the golden weeping willow, whose young branches are yellow. But the weeping willow sheds twigs, creating a maintenance problem, and its invasive roots sometimes clog drainage pipes. Its cousin, the corkscrew willow, looks like a conventional tree in summer when clothed in leaves, but in winter reveals twisted, contorted branches whose shapes must be seen to be believed. Some of the false cypresses also assume unexpected shapes, and the pencil-shaped variety of Virginia cedar called Sky rocket has a uniquely narrow form.

BARK THAT GETS ATTENTION

A number of trees are distinguished by bark that peels, or exfoliates, providing interesting textures and mottled colorings. One of the finest of these is the paperbark maple, whose red-brown bark peels off in thin sheets. Another is the Korean stewartia, an exceptional tree in any season of the year. In summer it bears white flowers, in autumn bright orange-red foliage, and all through the year its dark brown outer bark flakes off to reveal light-brown or green bark underneath. Also a splendid sight throughout the year is the peeling bark of the white or paper birch — which should, incidentally, be allowed to peel naturally. Pulling off the bark of any exfoliating tree is likely to injure the plant.

The shagbark hickory certainly belongs in the category of trees with decorative bark and so does the lacebark pine, whose bark peels to reveal gray, cream and white underlayers. The shredding brown bark of the Russian olive is pleasing and calls attention to the angular trunk of the tree. In warmer climates, the peeling light- brown bark of the crape myrtle accentuates the sculptural quality of the tree’s clustered trunks. “Tree barks,” observes one landscape designer, “are endlessly fascinating. Someday I’d like to design an entire garden around them.”

STALWART MINIATURES

Among smaller plants the choice for winter beauty is equally wide. In a class apart are the dwarf and slow-growing varieties of needled evergreens — hemlocks, spruces, pines, Japanese cedars, yews and junipers. The foliage of these miniature trees and shrubs often changes color in winter, and may vary from blue-green to gold to bronze-purple. Also useful for dressing up the winter garden are broad-leaved evergreens and deciduous shrubs with unusual shapes, berries, foliage or stem colors. Foremost on anyone’s list of shrubs for the winter garden are the broad-leaved evergreens that keep their looks in bitter cold. Among the most handsome and dependable of these are the mountain laurel and the two andromedas, mountain and Japanese. All three have deep green leaves, in both winter and summer. The beloved boxwood is, of course, vulnerable to damage from heavy snow and ice, which may snap its brittle stems. But its look-alike, Japanese holly, is more resistant to snow injury and may be clipped into any shape you wish. When the leatherleaf viburnum is protected from cold drying winds it will keep its handsome, crinkly leaves all year round.

The contorted branches of some deciduous trees have their counterparts among the deciduous shrubs. One of the strangest is the Harry Lauder’s Walking Stick, whose gnarled, twisting stems rival the shape of the trademark cane of the famous Scottish entertainer. Another is the vine maple, a shrubby tree whose long, limber branches trail across the ground or can be trained like a vine to grow against a wall. The twigs and branches of the winged euonymus, with their odd, corklike ridges, make this plant arresting even after its brilliant red autumn leaves have fallen.

BRONZES IN THE SNOW

Fully as useful to the garden are the shrubs with winter color in their leaves and stems. The foliage of drooping leucothoë turns a reddish bronze when the temperature drops, as does that of Oregon holly grape, the P.J.M. rhododendron and several other broad- leaved evergreens. Warminster broom provides the unexpected sight of bright green winter twigs in a sunny spot, and on a cold, crisp winter day, the pale green fluttering leaves of evergreen bamboo make lacy patterns against the snow.

Probably the most flamboyant winter color is that provided by the stems of the Tatarian dogwood, which may be crimson, purple or coral red, depending on the variety. For the strongest color, however, this shrub must be grown in full sun and heavily pruned in the Spring after it has flowered, since only new stems are brightly colored. This is also true of several other plants, notably kerria, whose new growth is a glossy green in winter.

One colorful winter-garden plant that looks tropical but in fact is dependably hardy as far north as Zone 7 is the Japanese aucuba, which may have solid green or green-and-gold leaves, depending on the variety. If you plant both male and female aucubas, you will get a winter bonus of large red berries — a dividend also offered by a number of other shrubs. Chief among them, of course, are the hollies. Except for the few self-fertile species and hybrids such as Chinese holly, these need male and female plants in order to produce berries, at least one male to 10 females — but the expense of acquiring a berryless male plant is well worth it. The shiny leaves and berries of the holly turn the winter garden into a scene straight out of a Christmas card.

A SPECTRUM OF BERRIES

Usually the berries of the holly are shades of red and orange, but several varieties have yellow berries, and one, the inkberry, has glossy black fruit. Also, though most hollies are evergreen, there are two deciduous species that bear abundant fruit. One is the possum haw, a Southern shrub with large orange-red berries; the other is the winterberry or black alder, whose stems are lined with coral-red berries, which birds relish.

Other plants besides hollies produce fruit, of course, and many of them last into winter. Pyracantha’s orange or red berries cling to its branches through much of the winter, and so do those of cotoneaster and barberry. The scarlet hips of two hardy shrub roses, multi- flora and memorial, are also long-lasting. A number of other shrubs put out berries of various colors: sea buckthorn bears bright yellow- orange berries that last through the winter; snowberry has white or pink-and-white berries, depending on the variety.

Perhaps the most dazzling berry display is put on by skimmia, a low-growing, well-proportioned shrub that is hardy in Zone 7. In a shady, protected spot, planted by twos, male and female together, skimmia will hold its holly-like berries all winter long, since one of its advantages (or disadvantages, depending on your priorities) is that its fruit is ignored by the birds.

CARPETS FOR COLOR

For textural variety beneath trees and shrubs you will want a ground cover or two. In a winter garden the choice includes a number of favorites from other seasons of the year. The spring- blooming epimedium, though it eventually loses its leaves, puts on an impressive autumn foliage display that extends well into the cold months. Wintergreen’s bronze-tinged foliage also performs well in winter, as do the purple-red leaves of the wintercreeper. Among evergreen ground covers, it’s important to identify those that provide a pleasing winter carpet without stifling any of the winter- blooming bulbs. Myrtle, for example, is sufficiently airy for a bulb bed, but English ivy and pachysandra permit virtually no sunlight to warm the ground beneath them.

Especially useful as evergreen ground covers along the edges of walks or to establish isolated spots of green are sarcococca, paxistima and evergreen candytuft; all three are shrublike rather than creeping. Several low-growing ornamental grasses also make excellent winter ground covers. One of the best is blue fescue, a true grass that forms small clumps and keeps its silvery-blue color all winter. Mondo grass and lily-turf, though not strictly grasses, have long, slender grasslike leaves that stay green year round.

THE SURPRISING FERNS

Finally, there are evergreen ferns, often overlooked as winter ground covers, though in fact some are hardy as far north as Zone 3. Probably the most familiar is the aptly named Christmas fern, but others that should be considered are the soft shield fern, ebony spleenwort, common polypody and the cliff brake fern. Ferns need some shade, even in winter, and in a winter garden should be closely massed, since they tend to become prostrate in cold weather. To supplement these plant materials in your winter garden consider three other decorative elements: mulches, birds and lighting. Mulches add textural interest where there are no plants, as well as covering areas that would otherwise be muddy in winter. Decorative mulches come in many forms, the choice depending on your taste and on availability. Some mulches are so uniform in color and size — buckwheat hulls, for example, or fir and pine bark — that they can be monotonous over large areas. Pine needles are attractive, if you can get them, but they can be a fire hazard in summer. Wood chips, often available from tree maintenance crews, tend to bleach to a silvery-gray color as winter progresses. Pebbles and stones create fascinating effects and, though expensive, need replenishing less often than organic mulches.

- - -

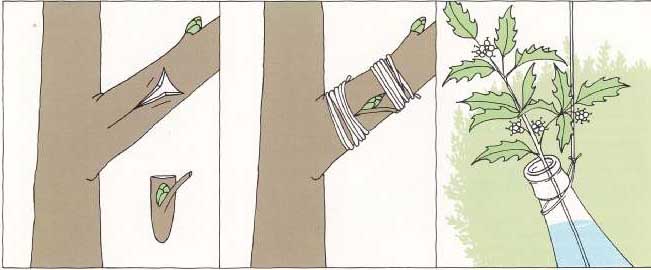

A MARRIAGE OF CONVENIENCE

To produce berries on a female holly without planting a male holly, graft male buds onto a female’s branches. Cut a 1 ½-inch-long T in the female’s bark. Slice an inch-long wedge with a leaf bud from a young male; pinch off the leaf but not its stem.

Pry up bark at the sides of the T-shaped cut and push the male bud down into it, using the leaf stem as a handle. Bind the graft with cotton string. As the holly matures, prune the faster-growing male branches in order to keep them within bounds.

Another way to obtain holly berries without planting berryless males is to cut several flowering branches from a male plant. Place them in a water filled container hanging among the branches of a female holly. The pollinating bees will do the rest.

- - - -

REFUGE FOR THE BIRDS

Birds can be mesmerizing — they provide life, color and movement in the otherwise subdued winter landscape. Attracting birds to your winter garden means providing food for them and giving them protection from the elements, from predators such as cats and from competitors such as squirrels. Birds value security, and any feeder should be placed not far from trees or shrubs that offer them refuge. As for protecting the feeder from cats and squirrels, numerous devices have been designed to thwart these creatures. They are usually available at garden-supply centers and they work with varying degrees of success.

In choosing a feeder, consider the kinds of birds you wish to attract. Some are seedeaters — and some seedeaters prefer to pick up seeds from the ground rather than from a feeder. Others are insect eaters that prefer suet to seed in winter; you can set suet out for them in a wire-mesh feeder. Most birds welcome the wild-bird seed mixture that you can buy in supermarkets, but for smaller birds like the tufted titmouse and the chickadee you might rig up a separate small tube of sunflower seeds, so they can eat without being pushed aside by blue jays or starlings.

= = = = =

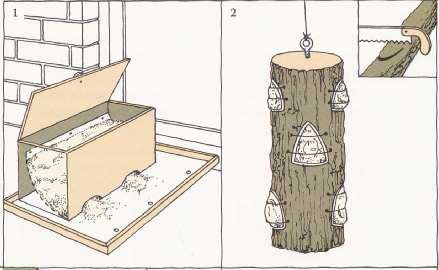

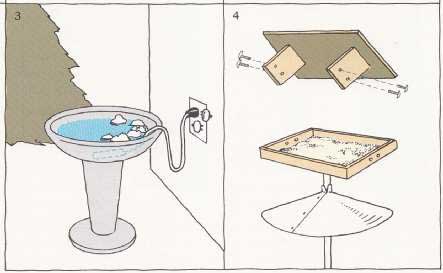

-- Inviting birds to your garden --

Birds will brighten a winter garden with their color, movement and sound if you keep them supplied with food and water. It’s better not to start feeding them, however, unless you intend to continue all winter, because birds soon learn to depend on your generosity and will perish if it’s withheld. The devices shown below will keep birds coming to your garden even if you go away for a few days. A seed hopper (1) provides food for several days, whenever birds need it. Even early birds have trouble catching worms when the ground is frozen, but you can feed insect eaters suet, a high-protein insect substitute, on logs (2) suspended from tree branches. Birds need unfrozen water (3) to drink, clean their plumage and stimulate oil glands in the feathers that insulate them from cold. A metal baffle (4) mounted beneath a feeder will keep cats and squirrels at bay.

THE LURE: FOOD AND WATER

1. Attract birds with seeds that pour automatically onto a platform from openings near the bottom of a hinge-topped box. The hopper is a piece of curved sheet metal fastened to the back wall of the box. Drill ¼-inch holes through the platform so rain will drip through, and attach the feeder to the window ledge for easy refilling.

2. Present suet on a log in which wedges are cut with a hatchet or a saw. To hold suet in place, stretch wire or weatherproof twine across if, wrapping the wire or twine around nails placed at opposite sides of the wedge.

3. Winterize a birdbath placed near the shelter of a tree by equipping it with an aquarium-type immersion heater weighted down with stones that also serve as perches. Birds, unlike human beings, don’t suffer from exposure to frigid air when damp.

4. To encourage timid birds, put food in full view on a platform with a roof that you can add to keep the seeds dry after the birds feel safe. Attach the roof by slipping bolts through the holes in the feeder edges and roof supports. A sheet metal collar makes the feeder cat- and squirrel-proof.

= = = =

A NATURAL FOOD STORE

Planting certain trees and shrubs will also draw birds to your garden. The winter fruits of dogwood, hawthorn, holly, pyracantha and bayberry are particular favorites; indeed, dogwood berries are popular with more than 75 different kinds of birds. The colder the winter, the more the birds will dip into this food supply.

But even as you watch your holly berries disappear, remember that birds cannot survive on berries alone. Once you start feeding them seeds, keep feeding them until spring arrives. Birds also continue to need water. If you have a birdbath, keep it filled; otherwise, set out a pan of water. In freezing weather, some wildlife enthusiasts set out warm water every morning for birds to use. Others install immersion water heaters in their birdbaths.

Night lighting can similarly run from the makeshift to the elaborate, but it’s best and safest to use low-voltage weatherproof wiring and fixtures. They can be purchased at most hardware stores. Before installing these fixtures permanently, you should try various combinations and angles of light, keeping in mind that a winter garden should be lit somewhat differently from a summer one. A winter garden is viewed primarily from indoors, whereas a summer garden is lit for outdoor sitting and strolling. Usually a small adjustment will suit the lighting needs of both seasons.

LIGHTING THE NIGHT SCENE

Where you place the lights varies with each garden. Sometimes a tree looks better illuminated from above, sometimes from below.

Some shrubs may be effectively lit from the front, others silhouetted from behind. Often sculpture is enhanced by side lighting, bringing out its modeling. The intensity of the light also makes a difference — you may discover that a 15-watt bulb with its soft light does more for your garden than a brighter one. One thing, however, is essential: don’t install an outdoor light so that it shines in your neighbor’s eyes. The winter scene you create to view from your windows should be delightful from his windows, too.

= = = =

Brilliant color under balmy skies

Gardeners in areas where winters are mild may have to contend with occasional frost, but with luck they are never without flowers. Many of these flowers bloom on evergreens, often the stalwarts in Southern gardens just as they are in the North. Indeed, they may be identical with evergreens that flower later in Northern gardens. If you go to Savannah in February, for example, you will be greeted by azaleas in full bloom. In the antebellum gardens of Charleston, South Carolina, the rhododendrons will be out.

Azaleas and rhododendrons by no means exhaust the possibilities. A glorious array of other broad-leaved evergreen plants bursts into bloom in winter in the gentle climates of Zones 8-10. A few are trees, several are vines, a great number are shrubs. Winter is the flowering time of the sweet-smelling Carolina jessamine and of the frothy pink-and-white strawberry tree. In Southern California a succession of acacias flower through the winter, and all through the Old South the beautiful camellia unfolds its breathtaking blooms in a multiplicity of colors and shades. Sweet osmanthus, which Deep South gardeners call tea olive, has small flowers but such a delicious fragrance that it’s a favorite winter-bloomer.

Like most evergreens, these Southern plants often need special growing conditions. Many need the filtered sunlight found beneath the branches of tall trees or the shade of a protective wall. Year- round moisture may also be a requisite. Their foliage, vulnerable to cold, drying winds, fares better where it’s humid year round, and many need mulches to keep shallow roots moist. As a group they are tender plants, but some are more so than others. The large, lush flowers of the Chinese hibiscus, for example, are safe only where temperatures remain above 50°. On the other hand, a number of Southern evergreens actually need a period with some chilling to produce the best blooms. To Northern gardeners, accustomed to equating swelling buds with the zephyrs of spring, it may be a surprise that the delicate camellia is forced into flower when brushed by the brisker air of a Southern winter.

Rhododendron cilpinense, a hybrid that is hardy to Zone 8, brightens an entranceway in Seattle with winter blooms. The flowers open pale pink, then gradually fade to white.

Trees ablaze--Among the most spectacular Southern evergreens that flower in winter are the small trees. Although some are technically shrubs with color with multibranching trunks, they reach heights of 30 feet, spread even wider, and possess an ornamental value so great they are commonly used as centerpiece plants. The acacia, for example, is prized for feathery gray-green foliage as well as flowers, the ever green pear for thick, shiny, leathery leaves, the aptly named straw berry tree for bright red strawberry-like fruit.

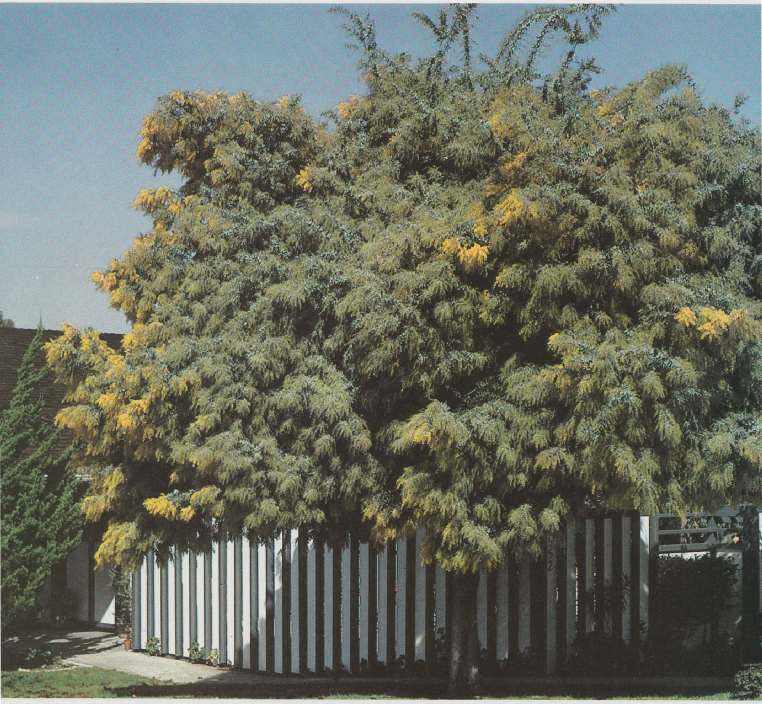

An Acacia baileyana, laden with fragrant yellow flowers, decorates a winter garden in the mild climate of Zone 9 in Southern California.

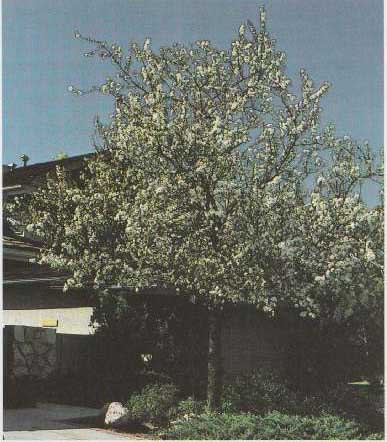

Hardy as far north as Zone 8, the evergreen pear, Pyrus kawakamii, puts on a dazzling display of white winter flowers that all but obliterate its foliage.

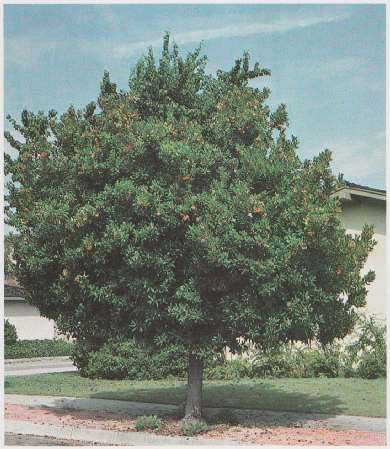

Last year’s fruit and this year’s winter flowers hang on the branches of the strawberry tree, Arbutus unedo, which is hardy as far north as Zone 8.

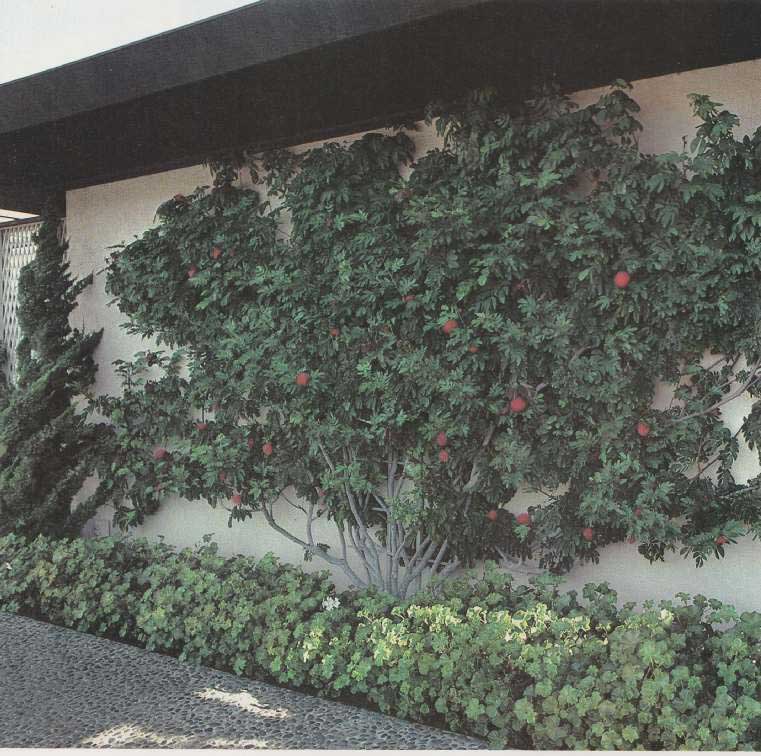

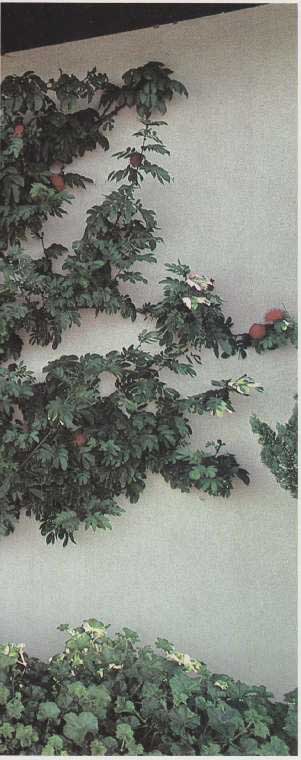

Wallflowers to catch your eye

Winter-flowering evergreens that cling to walls, cover trellises and spill from wrought-iron balconies are so common in Southern gardens that they are virtually a trademark. Some are vines, like the scarlet-flowered bougainvillea of Zones 9 and 10, and the equally tender and luxuriant flame vine, whose orange blossoms often crown terra-cotta roofs. Others, like the calliandra and Carolina jessamine shown here, are shrubs with such long, trailing branches that they lend themselves well to being espaliered.

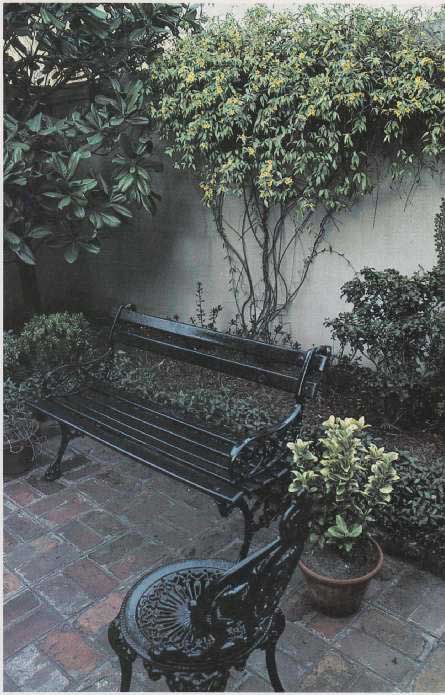

Carolina jessamine, trained to grow on a garden wall, perfumes

the winter air with yellow flowers. A Southern favorite, it’s grown in

Zones 8-10.

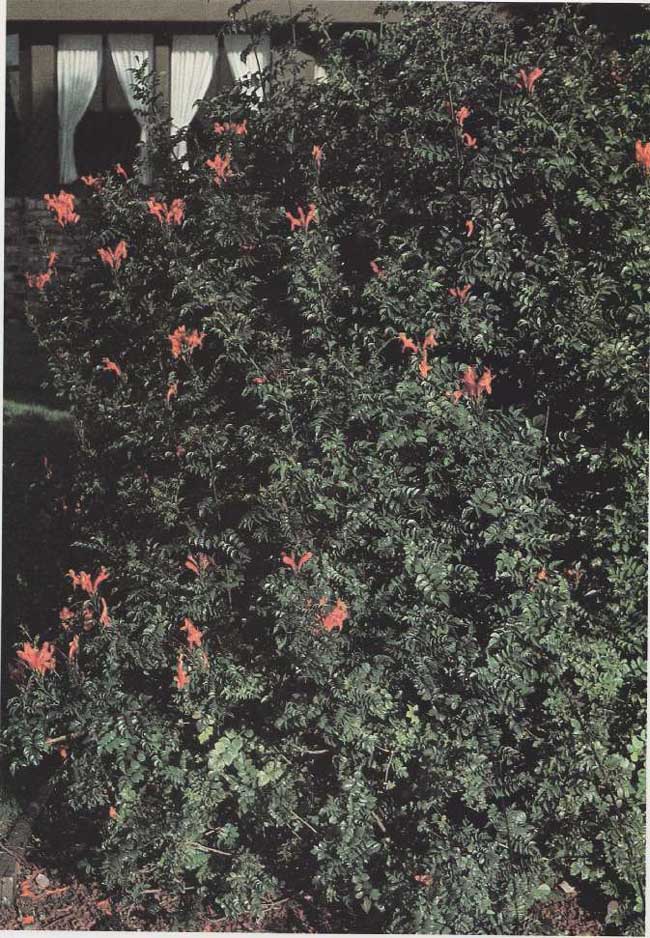

Years of careful pruning translated this red-flowered calliandra into a wall wide evergreen cloak. Frequently called the powder-puff shrub, calliandra is hardy in Zones 9 and 10.

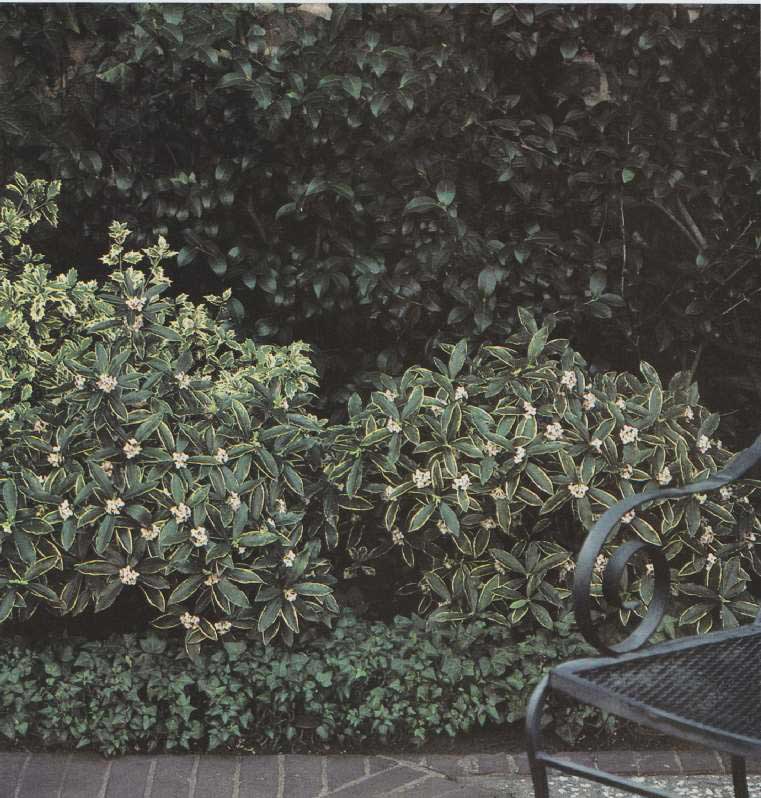

The versatile Southern belles

The winter-flowering shrubs of Southern gardens are versatile as well as decorative, serving either as focal points or as formal or informal hedges and privacy screens. Their foliage can be delicate or sturdy, their ultimate shape compact or sprawling, their blossoms demure or vibrant. Some are adaptable, like Indian hawthorn, which survives despite poor soil and ocean spray. Others are demanding, none more so than winter daphne, which repays intensive care with a pervasive fragrance that makes all the work worthwhile.

A variegated winter daphne, hardy to Zone 8, brightens a terrace garden; the dainty pink flowers fill the late- winter air with roselike perfume.

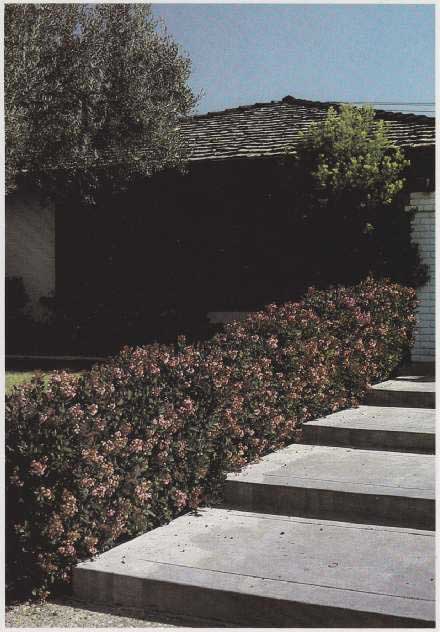

Indian hawthorn, clipped into a formal hedge, lines a broad, outdoor stairway. These popular evergreens bloom all winter long south of Zone 8.

Bright red funnel-shaped flowers and glossy foliage decorate a neatly pruned Cape honeysuckle all winter in Zones 9 and 10.

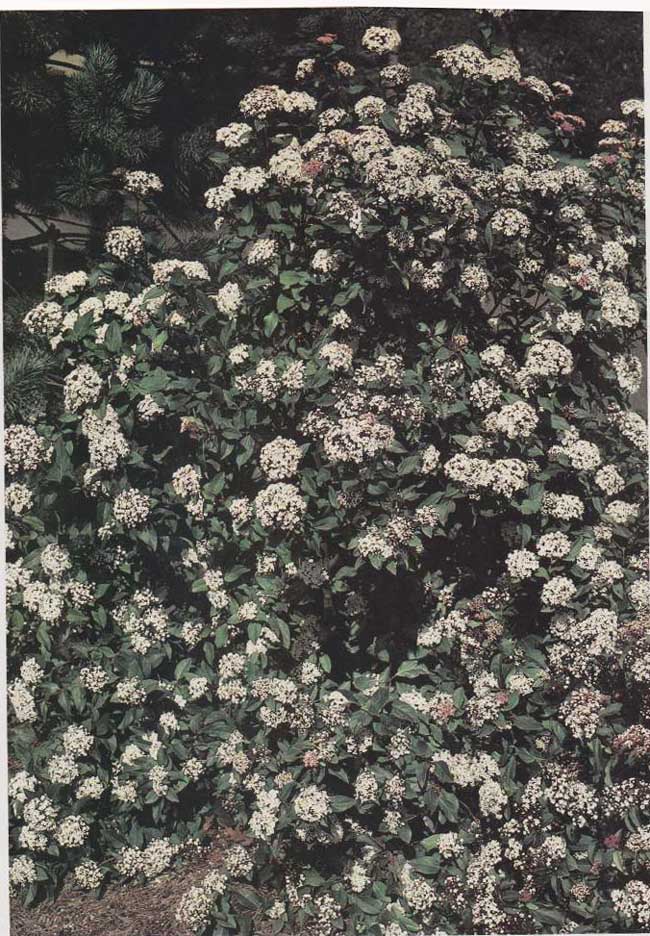

Clusters of tiny winter flowers rest like snow on the branches of laurestinus, a care-free viburnum that grows in Zones 8-10.

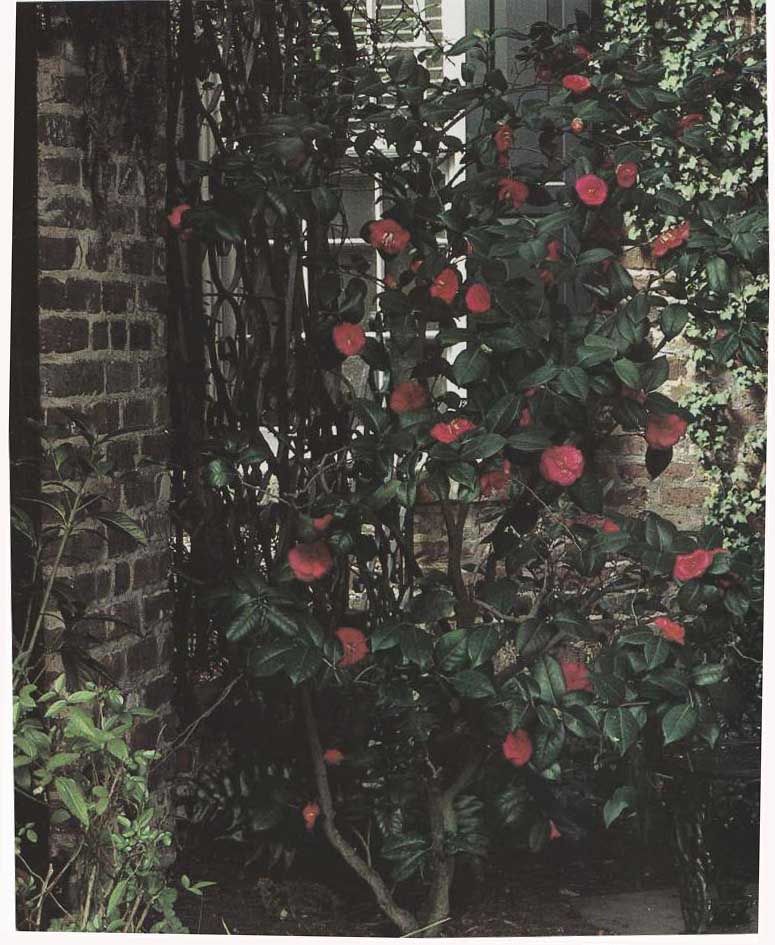

A Camellia japonica shares a shaded patio garden in Charleston, South Carolina, with a Nandina domestica whose berries echo the scarlet blossoms of the camellia. Japonica is probably the most popular of all the winter-flowering evergreens in Zones 8-10.

Articles in this Guide are based on now-classic Time-Life Encyclopedia of Gardening Series from the 1970s ... a timeless series, some titles of which are still available in libraries and bookstores... see our Amazon Store for purchasing options.