A gardener who lives in northern Maine has winter aconites in bloom in early February. Another gardener in upstate New York enjoys violas and winter-flowering heaths straight through the cold months. A Long Island gardener reports having a crocus in bloom the day before Christmas; an Indiana gardener cuts forsythia that will bloom indoors weeks ahead of schedule. Admittedly winter flowers are no match for the spectacular displays of summer, but that never seems to matter. “There’s as much joy in finding a single flower in February,” says one veteran, “as a whole border in June.”

Getting plants to flower in winter is a tantalizing game, especially for gardeners living in the broad central belt of the United States represented by Zones 5-7 (map). What will come up? And if it comes up, will it flower? There is always an element of adventure. South of this belt, in Zones 8-10, there are plenty of opportunities for winter flowers. North of Zone 5, there is often little chance of seeing flowers until spring.

Nevertheless, even the cooler parts of the United States and southern Canada have a number of plants that will flower in winter. Some do so naturally. Others normally flower in late autumn or early spring but have been induced to extend or advance that period of bloom. Zealous winter gardeners narrow the gap in their gardening calendars to a few weeks around the turn of the year. With luck and weather permitting, they sometimes bridge the gap completely by creating conditions that mimic Indian summer or early spring.

The key to successful mimicking is warmth. To flower ahead of or beyond their normal schedule, plants need to be shielded from the harshest rigors of winter. Some gardeners use the shelter of a pit greenhouse. But if you have a garden of average size, you should have little trouble providing propitious conditions in the open air. First, look at your garden and identify places that are warmer than others, where the snow melts soonest and there is ample winter sunlight. If there are rocks or a south-facing masonry wall to absorb the sun’s heat and radiate it through the day and into the evening, so much the better. A furnace or fireplace chimney will radiate some heat through the bricks, and a ground-level window may leak enough warm air to affect plants growing immediately outside.

A spray of winter-flowering witch hazel, brought inside to be forced into early bloom, reflects the shape of a witch-hazel bush in the snow-filled garden. On the bush, buds are just beginning to show color.

= = = = = =

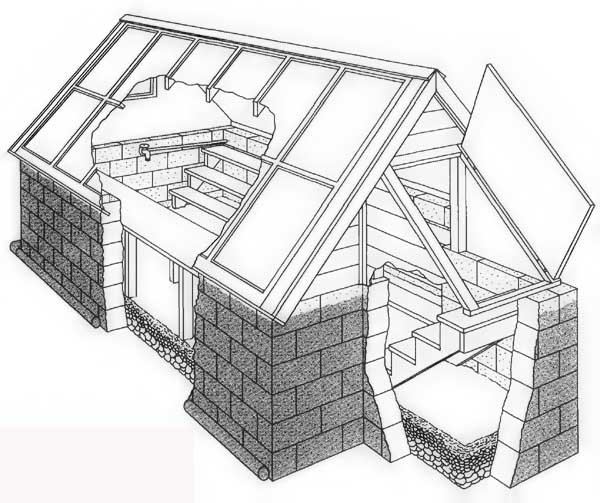

A solar-heated underground greenhouse

A pit greenhouse is basically a hole in the ground roofed with glass and warmed by the sun. Insulated by the surrounding soil, it needs little or no artificial heat to keep temperatures above freezing. There the winter gardener can raise vegetables, start seedlings or store tender perennials.

Choose a sunny, well-drained site; the greenhouse can be either freestanding or adjoin a house wall. Excavate to a depth of 5 feet and line the walls with concrete blocks. Extend one end of the pit to allow for a door and stairway. Put down a 1-foot layer of stones graded from large to small and cover with 6 inches of tamped-down soil. Plastic drain tiles outside the base of the walls improve drainage.

Roof the south side of the pit with green house glass or plastic panels and the other sides with fiberglass insulation between boarding. A window opposite the door and a vent in the north roof keep the pit from becoming too warm. Provide electricity for a small fan, a light and a heater. On cold nights and gray days a layer of straw covered by a tarpaulin insulates the glass roof.

A potting bench, running water and shelves for potted plants and tools (rear) provide finishing touches for a pit greenhouse.

= = = = = = =

CAPITALIZING ON WARMTH

Second, be sure this area is protected from cold prevailing winds by a house wall, a solid fence or a dense evergreen hedge.

Third, shun low areas that trap down-flowing cold air and are subject to early-fall or late-spring frosts. Fourth, take advantage of structures that will trap or convey heat. Finally, improve the soil by digging in a mixture of compost, peat moss and sand; loose, well- drained soil won’t freeze as hard as damp clay soil.

These ideal conditions are often found in a rock garden, particularly one that faces south and has a light, well-drained soil. In addition to offering the warmth of the rocks, a rock garden is a logical setting for many of the small plants that flower in winter, especially bulbs native to mountainous areas. For many gardeners the hardy bulbs are the first choice for winter bloom. A dozen or so can be tucked into a space no larger than a man’s handkerchief and, blooming in succession, provide color almost all winter.

After roses, chrysanthemums and the other floral vestiges of summer have faded, two kinds of bulbs — crocuses and colchicums — bring color to the garden from fall until the end of the year. Until a week or so before Christmas the late-flowering fall crocus, Crocus Iaevigatus fontenayi, produces flowers that are buff-colored on the outside and lilac inside. It’s quickly followed by the bright orange Crocus vitellinus and Crocus imperati, with purple stripes on its white or lilac petals. Colchicums look like large crocuses, and one species, Coichicum speciosum, is almost a foot tall and resembles a tulip, though the plants are not related. Colchicums are available in shades of mauve, lavender or white, and have one curious feature. Their foliage, nonexistent when the bulbs are in bloom, suddenly appears in spring and grows about a foot tall, dying back in midsummer. You will want to plant colchicums where their broad, rather coarse foliage will be disguised by other plants.

THE SPECIALTY BULBS

These bulbs may not be available at garden centers, but can usually be bought by mail from firms that specialize in bulbs. They should be ordered in late summer and planted when they arrive, so roots will have time to develop before the ground freezes. Plant each at a depth equal to three times its maximum diameter.

The earliest spring crocuses appear while snow is still on the ground. If the snow is only a few inches deep and the bulbs get enough sunlight, they may even win the flowering sweepstakes and appear in early January, before their close rivals, the snowdrops and winter aconites. Note, however, that these are not the familiar Dutch hybrid crocuses but species crocuses, and they are marvelously varied. One of the earliest to bloom is Crocus sieberi, a handsome lilac-to-purple flower from the mountains of Crete and Greece.

Another species crocus is C. chrysanthus; varieties range from cream color and orange-yellow to various shades of light blue. Or you may want to try C. susianus, the cloth-of-gold crocus, with stripes of brown on a golden-yellow background.

DEFYING WINTER SNOWS

Species crocuses should be planted in late summer or early fall so the bulbs will have a chance to go through a warm period to develop their roots, followed by a cold period to start top growth. If this cold period is delayed by a late winter, flowering will also be late. The bulbs should be allowed to bake in summer through a period of dry heat; they should never become waterlogged. Properly cared for, they are marvelously sturdy. They will sprout through snow and flower above it, and if buried by fresh snow, they will bloom anew when they have full access to sun. In fact, they are so dependent on light that they won’t open on a cloudy day.

Shortly after the crocuses, and sometimes simultaneously with them, the snowdrops and winter aconites make their appearance. True to their name, the snowdrops are undeterred by snow, and will last for several weeks. If temperatures drop below freezing they may become limp, but they will resume their jaunty demeanor as soon as the weather improves. Most gardeners are familiar with the diminu tive variety, Galanthus nivalis, but may be unaware of the larger Galanthus elwesii, with stalks 10 inches tall and white flowers an inch or more wide marked with emerald green on the inside.

Unlike crocuses, snowdrops need some shade for strongest growth. So too do winter aconites, whose bright yellow flowers look like overgrown buttercups — a plant to which they are related. Winter aconites differ from crocuses and snowdrops in being unusually dependent on moisture. If their bulblike corms seem dried out when you get them, soak them overnight before planting them in soil that remains moderately moist all year.

THE STURDY CYCLAMEN

By February, assuming the weather has moderated a bit, these pioneering stalwarts are likely to be joined by a number of other early-flowering bulbs. One of the loveliest is the Coum cyclamen, a small relative of the florist’s cyclamen. In fall it produces attractive kidney-shaped foliage, and then in late winter it bears a clump of small, elegant white, pink or red flowers. The Coum cyclamen needs excellent drainage and, in cold areas, a protective mulch.

Several dwarf irises that grow from bulbs can also be expected at this point. Most notable are Iris reticulata, with deep violet flowers, and Iris danfordiae, with bright yellow flowers. The flower stalks of these plants are only 6 inches high, but their leaves may be a foot or more long and have sharp tips for pushing through frozen ground or snow. The irises may develop a fungus disease in summer unless they are kept bone dry. They can usually be protected by surrounding them with sand, but you may dig them up in spring after their foliage has yellowed and store them indoors until fall.

FINDING GOLD IN FEBRUARY

Another group of early-blooming bulbs that needs to be protected from excessive moisture belongs to the narcissus clan. The earliest is the tiny Narcissus asturierisis, just 2 ½ inches high, which looks like a conventional daffodil seen through the wrong end of a telescope. Its bulbs are often hard to find. Slightly larger is the hoop- petticoat daffodil, with funnel-shaped flowers. Although most varieties of this species don’t bloom in Northern gardens until March, two varieties, foliosus and romieuxii, may flower during a February thaw — but they will disappear for the year if the temperature drops again. A third daffodil that may flower at this time is February Gold, which grows to a more standard size.

As the winter-flowering bulbs come and go, you may wish for the constancy of longer-lasting color. The wish can be fulfilled in part by a handful of perennials and two somewhat bizarre annual vegetables, ornamental kale and ornamental cabbage. These look-alike plants, which resemble nothing else in the flower garden, have tight heads of leaves, opening from the centers, which may be off- white or deeply tinged with pink, rose, red or purple at the centers, shading to emerald around the edges. When started from seeds in midsummer, they put on a startling display that may last into January. The color of individual plants cannot be predicted, however, so it’s best to keep seedlings in pots until they begin to show color. Then place them in the garden to suit your color scheme.

= = =

PRUNING SHRUBS FOR INDOOR BLOOM

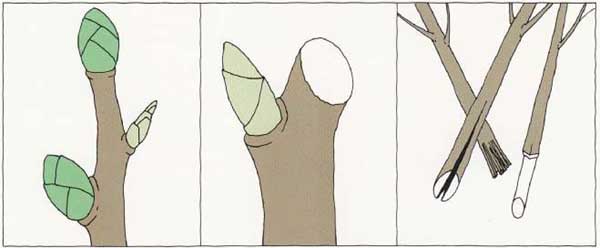

To obtain bountiful winter flowers indoors, cut branches from early blooming shrubs that bear numerous large, rounded flower buds (dark green). The smaller, pointed buds (light green) will produce leaves.

Cut the branches just above a leaf bud at a 45 degree angle in the same direction that the bud is pointing, using sharp pruning shears. This angled cut is not as likely to damage the leaf bud as a cut made straight across the branch.

To help cut branches absorb more water, slit the ends of slender stems to a depth of 3 to 4 inches. For thicker stems, crush cut ends with a hammer, or shave outer bark to expose the water-absorbing layer just beneath.

= = =

THE RELIABLE HELLEBORES

Of the several perennials that flower in winter, the most valuable for winter gardeners of the North are probably the helle bores. These plants from the Alps can be grown as far north as Zone 4 and as far south as Zone 9. The most striking is the Christmas rose, which is not really a rose but like all hellebores is a member of the buttercup family. Its blooms are dazzling white, 2 to 3 inches across, with yellow stamens. As they age, the petals turn pink or green.

With luck and moderate weather, the Christmas rose may indeed bloom at Christmas, but an appearance in late January or February is more likely. “No one ever told my Christmas rose that we celebrate the event in December,” one gardener said. A few weeks later the flowers of three other hellebores appear. The cream- colored Lenten rose almost always blooms by March; there are also hybrids with green, brown or purple flowers. The green flowers of setterwort and Corsican hellebores bloom in time for St. Patrick’s Day. All hellebores have lustrous, evergreen foliage.

Hellebores can be difficult to start, but once established, they are extremely hardy. They are best begun from clumps bought from a reputable nursery. Shade is essential, especially in midsummer, and they need a rich neutral-to-alkaline soil deep enough to accommodate a long taproot. Because of the root, hellebores don’t usually survive transplanting. The plants may take several years to reach flowering size, but the wait is worth it. A mature hellebore not only puts on a good midwinter show but provides cut flowers for bouquets that last up to 12 days.

Another plant that will bloom in the coldest months of the year is the Johnny-jump-up, a relative of violets and pansies. Few things are more astonishing than the sight of its dainty blue, yellow or white flowers nestled against the ground when the weather is at its worst.

By late winter the Johnny-jump-ups and hellebores compete with several other perennials. One of the most rewarding is the Amur adonis, with fernlike foliage and cup-shaped yellow or apricot blossoms up to 3 inches wide, that may remain fresh for two months. Others are two pulmonarias, cowslip lungwort and Bethlehem sage, which grow a foot or more and have blue or reddish-violet funnel- shaped flowers. Completing the list is a Himalayan import, Primula denticulata, the earliest of the primroses. Himalayan primrose has dainty ½-inch flowers that are violet, purple or white.

Just as the cool, misty slopes of the Alps and Himalayas are the source of many of the winter-flowering bulbs and perennials, so the cool, misty moors of Scotland are the source of another group of favorites: the winter-blooming evergreen heaths. One of the prettiest of these low-growing shrubs, Erica carnea, produces tiny white, red, pink or purple flowers right into spring. It comes in many varieties, perhaps the sturdiest being King George. Writer-photographer Mildred Graff tells of going out to take a picture of King George’s rosy flowers in 15° weather in a gale-force wind. In the time it took to brush snow off the plants, her fingers stiffened and the camera shutter refused to work properly. Her picture was useless — but the King George stayed sprightly and unperturbed.

= = = =

Harbingers of winter’s end

A number of early-blooming bulbs are so hardy that they flower even before the soil has fully thawed, opening their bright petals against patches of glistening snow. If they are planted in sun-catching, south-facing sites, snowdrops and winter aconites, the earliest of the bulbs, may bloom in January in the North —sometimes as early as New Year’s Day. Typically, species crocuses appear in February, followed by squilis, chionodoxas and a handful of the hardier daffodils. Most of these bulbs can survive a late storm quite handily, emerging from under a layer of newly fallen snow. They have a still better chance if they are planted in the quick- draining soil of a rock garden or on a slope.

To ensure that they get enough light to promote early flowering, early- blooming bulbs should not be planted under evergreens or against a north wall. Dense ground covers such as ivy may also shade them from sufficient light, it’s safer to plant them among the more open-growing periwinkle, or alongside low-growing wildflowers.

Early-blooming crocuses like these, emerging in late winter, are most striking when planted in drifts of 25 or more.

- - -

(l) The round cups of winter aconites pop out of the ground by mid-March in bitter-cold climates; (r) Looking like purple-dyed daisies, Greek anemones unfold their petals under the first rays of the March sun.

(l) The glory-of-the-snow resembles Siberian squill (opposite), except that its petals face up to the sky. (r) In its early stages, this white squill’s flowers are a soft, silvery blue color that pales as the foliage ages.

The sharp leaves of snowdrops can push up through ice and frozen soil, before the bell-like flowers open. Harput irises, the gold spots on their petals flashing in the sun, typically rise out of the gray slush of March.

Star-shaped Siberian squills, which bloom in March, are notably prolific, spreading with each passing year. With broader petals than its violet counterpart above, the yellow Danford iris may bloom in late February.

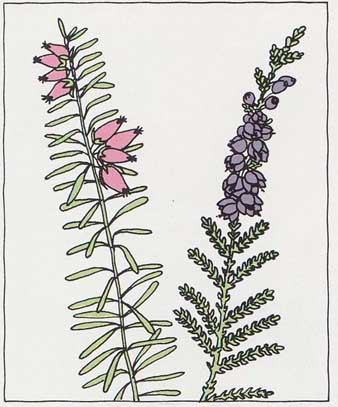

COLORFUL RELATIVES

The heaths are closely related to the heathers, but the two plants are quite different in appearance and behavior. Heaths have needle-like leaves and bloom in winter and early spring; heathers have scalelike leaves and flower in summer — although the winter foliage of some varieties is so spectacular that it too is an important source of winter color. When hit by frost, a hillside of heather becomes a kaleidoscope of reds, yellows, purples, bronzes, oranges, browns, pinks and olive green. Indeed, a gardener must exercise restraint to avoid gaudiness. Furthermore, as you walk around a clump of heather it changes hue, for its colors characteristically develop most vividly on the side facing the sun. Heather seen as orange from one point may be green when viewed from another side. Heaths and heathers like sandy, acid soil and the cool, moist conditions of their natural environment. They are hard to grow in dry parts of the United States and in the warm, humid Southeast, where they live for only four or five years. They also need sunlight but at the same time protection from winter sun and wind, a condition that can usually be met with an eastern exposure and by interspersing them with other shrubs. A heavy mulch is often necessary to keep the roots from drying out. Otherwise, they are relatively trouble-free, needing only annual pruning — in late winter or very early spring for heathers and just after flowering for winter- blooming heaths — to keep the plants from looking scraggly.

= = = =

HEATHS VERSUS HEATHERS

From a distance, heaths and heathers look very much alike and in fact the two plants are related. But a close look will reveal differences. Heath (left) is the common name for the genus Erica, which is noted for its needle-like foliage and urn-shaped flowers. Heather (right), or Calluna, has scalelike leaves and bell-shaped flowers that divide at the rim into four parts. Most heat bloom in winter and spring, while heather blooms in late summer and early fall.

= = = =

DESIGNING DRIFTS OF COLOR

1. Beds of heath and heather look most natural when planted in irregular drifts across a sunny slope protected from winter winds. First sketch the drifts on paper, allowing enough room in each drift for at least three plants. Then transfer the plan to the garden, outlining each area with sand or clothesline. Although no two adjacent drifts should contain the same plant variety, the whole bed will look more unified if no more than a total of five different color varieties is used. Heaths and heathers grow best in a sandy soil enriched with peat moss or other organic material.

2. If plants come from the nursery in plastic containers, remove the containers and gently loosen the fine, fibrous roots with your fingers. Roots will then penetrate the new soil more easily, becoming quickly established.

3. If plants are in peat pots, crush the pot bottom to hasten root penetration, and set the pot directly in the prepared hole. Water well and fill the hole with equal parts of soil, peat moss and sand. Break off the pot rim if it extends above the soil; otherwise it will act like a wick, drawing off water. Plants will die if the roots dry out.

4. To keep heat/is and heathers bushy and to stimulate blossoming, shear back dead growth to healthy green wood, removing one half to two thirds of the plants’ height. Shear spring heath right after flowering, other species in spring just before new growth begins.

5. Propagate new heath and heather plants by bending a low branch of an established plant to the ground and burying it so the branch tip extends upward. Hold the buried branch in place with a bent wire until roots develop, then snip the new plant from the parent and transplant to the desired location.

= = = =

BEWITCHING BLOSSOMS

A number of other shrubs, both small and large, also contribute bloom to the winter garden. Chief among them are the witch hazels, a group of large gray-barked deciduous shrubs the size of small trees. Witch hazels grow from Zone 8 north, and open their yellow or red- to-yellow blossoms at various times all through winter, depending on the species. The earliest to flower is the Virginia witch hazel; its small yellow flowers appear as the leaves drop in fall, and remain on the tree into December. During a mild spell in January, you may see the yellow-to-red flowers of the vernal witch hazel, which unrolls long ribbon-like petals in good weather and rolls them up again when temperatures drop; it will continue to do so, with increasing frequency, until early spring. While the vernal witch hazel is still performing, it will be joined by the Chinese and Japanese witch hazels. The Japanese is the hardier of the two, but the Chinese has the more spectacular blooms; its branches are thick with red or golden-yellow ribbon-like flowers that are fragrant and last for weeks.

Yellow flowers abound on winter-blooming shrubs. Winter jasmine, a trailing deciduous shrub, exhibits small tubular yellow blossoms from midwinter to early spring. Not sturdy enough to stand alone, it looks best trained on a trellis or cascading over a wall. The Cornelian cherry, a shrubby relative of the flowering dogwood, also has a profusion of yellow flowers in late winter. Wintersweet and winter honeysuckle, neither a particularly elegant shrub, make up for their lack of shape with extremely fragrant flowers that bloom in mild spells from December to March. And the yellow-flowered evergreen shrub, leatherleaf mahonia, blooms as early as February.

FROM YELLOW TO WHITE

Color other than yellow can be obtained from the silver-pink catkins of the pussy willow, which may emerge in February on the native American shrub, and later but more luxuriantly on the French pussy willow. The evergreen shrub Sarcococca hookerana bears white blossoms in February — even earlier in the South.

Southern gardeners, in fact, have a cornucopia of winter bloom not available to gardeners in the North. The familiar springtime bloom of azaleas in Northern gardens emerges in Zone 9 in the South and along the West Coast in the middle of winter. Two hybrid evergreen groups in particular, the Kurume and Indica azaleas, will bloom from late December through early spring. And few Southern gardeners can resist the opportunity to have magnolias in bloom a month after Christmas. Although the evergreen magnolias bloom in late spring and summer, the smaller deciduous star magnolia puts on a display of fragrant, snowy-white flowers in February in Zone 8 and as early as January in Florida and other parts of Zone 9.

THE FINEST OF ALL

But for winter bloom in Southern gardens probably no plant can surpass the camellia, the finest of all winter-flowering shrubs.

Originally brought from China to Europe, the camellia prospered in areas where summers were warm and winters were cool enough to give them some chilling. Well before the Civil War more than 100 varieties of camellia were being cultivated in the gardens of Charles ton, South Carolina, and today they are widely grown in many parts of Zones 8 and 9, and even (though rather unpredictably) in Zone 7.

= = = =

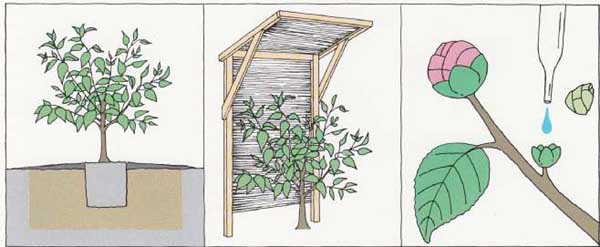

CARING FOR CAMELLIAS

(l) To ensure that a camellia, which has shallow roots, is not smothered under too much soil, set the plant in a prepared hole so the root crown is 1 inch above ground level. The plant will settle, but not enough to harm it.

(m) During their first winter, protect the newly planted came/has from strong winter wind and sun by erecting a shelter of 1 -by-2s covered with bamboo or burlap. The shelter should especially block the morning sun,

(r) To stimulate extra-large camellia flowers, remove the leaf bud closest to the flower bud you wish to enlarge, leaving the leaf calyx in place. Put a drop of gibberellic acid solution, a growth hormone, in the leaf calyx.

= = = =

Selections for a mild climate

For the gardeners who live in southern Florida and Texas, and along the coast of Southern California, winters are so mild that it’s possible to have annuals and perennials that bloom in December and January. The annuals selected for this purpose are called winter-hardy, meaning they are likely to survive occasional short bouts of cold. A list of favorite annuals and perennials is at the right, along with the best time for planting.

AEONIUM ARBOREUM ATROPURPUREUM (black tree aeonium) Set out plants in early spring or early fall.

ANTIRRHINUM MAJUS (snapdragon) Set out seedlings in early fall.

BELLIS PERENNIS (English daisy) Sow seeds in late summer or early fall.

CALENDULA OFFICINALIS (calendula, pot marigold) Sow seeds in late summer or early fall.

DIMORPHOTHECA HYBRIDS ( Cape marigold, star-of-the-veldt) Sow seeds in late summer or early fall.

IBERIS UMBELLATA (globe candytuft, annual candytuft) Sow seeds in fall.

KALANCHOE LACINIATA (kalanchoe) Sow seeds in spring.

LAMPRANTHUS SPECIES (ice plant) Set out plants in early spring or early fall.

LATHYRUS ODORATUS (sweet pea) Sow seeds in late summer or early fall.

LOBULARIA MARITIMA (sweet alyssum) Sow seeds in fall.

MATHIOLA INCANA ANNUA (common stock) Sow seeds in early fall.

NEMESIA STRUMOSA (nemesia) Sow seeds in fall.

PAPAVER NUDICAULE ( Iceland poppy) Sow seeds in late summer or early fall.

PRIMULA POLYANTHA (polyan thus primrose) Set out plants in early fall.

SCHIZANTHUS WISETONENSIS (butterfly flower, poor man’s orchid) Sow seeds in fall.

SENECIO CINERARIA (cineraria) Set out plants in spring or fall.

SEDUM SPECIES (sedum) Set out plants in early spring or early fall.

VIOLA TRICOLOR HORTENSIS (pansy) Set out plants or sow seeds in late summer.

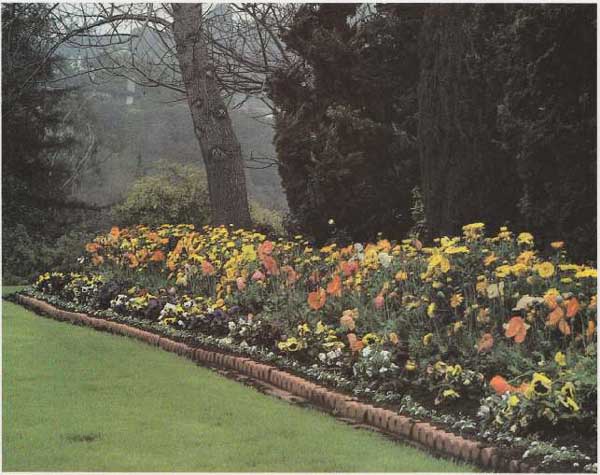

A midwinter border that includes annual calendulas blooms in a California garden against c and a bare elm.

- - - -

The best-known camellia is probably the Camellia japonica, often called simply japonica. Its large white, pink or red blossoms begin to appear in December or January and put on a show at least until the middle of March. Second in popularity is the Camellia sasanqua, which has smaller though more abundant flowers and blooms in late fall and early winter. The sasanqua camellias do equally well in sunlight or shade — unlike the shade-loving japonicas. A third species, Camellia reticulata, with large flowers but fewer leaves than the other two, has become a favorite of California gardeners. It blooms in late winter or early spring in Zones 8 and 9.

ANNUALS FOR THE HOLIDAYS

For winter gardens in the South and on the West Coast there are also flowers of another plant category: hardy annuals. These plants bloom in summer in Northern gardens, but can withstand the frosts that sometimes descend even on the subtropical gardens of Zones 9 and 10. Among them are such favorites as calendulas, Cape marigolds, sweet alyssums, sweet peas, stocks, hollyhocks and petunias. Seeds planted in fall will flower by December or January.

To match this performance, a Northern gardener would have to resort to a bit of subterfuge. He could, for example, move his winter gardening activities into the relative warmth of a pit greenhouse, a kind of cross between a greenhouse and cold frame. In this under ground haven heated by the sun, he could extend the blooming season of such autumn plants as chrysanthemums or fall-blooming irises and crocuses, to provide midwinter bouquets. Or he could advance the season of certain spring-blooming trees and shrubs by cutting branches still in tight bud and forcing them into early bloom indoors. Forsythia is commonly forced into bloom in this way. Other likely candidates are flowering dogwood, flowering quince, azalea and spirea, and such flowering fruit trees as apple and pear.

The technique of forcing plants into bloom in advance of their season is simple. The cut branch is split, peeled or crushed to improve its water intake, then wrapped in newspaper and placed in a vase of tepid water in the coolest room in the house for several days, until the buds begin to open slightly. At that point remove the newspaper and move the vase to a brightly lit place, though not in direct sunlight, which would dry out the buds. The flowers last longer if the air is cool and moist.

A MATTER OF TIMING

Successful forcing is a matter of timing. How soon you can move cut branches indoors is largely up to nature, and depends on the plant’s cycle of growth as well as the vagaries of the weather. Achieving winter flowers indoors can be a matter of chance. One Northern gardener watched in dismay as a child broke a branch from a spring-flowering azalea in mid-February. On an impulse, he carried the branch indoors and put it in water. Ten days later he was handsomely rewarded when the azalea burst into a blaze of pink flowers, two months ahead of its normal schedule.

Prev. | Next

Articles in this Guide are based on now-classic Time-Life Encyclopedia of Gardening Series from the 1970s ... a timeless series, some titles of which are still available in libraries and bookstores... see our Amazon Store for purchasing options.