Just as the normal human reaction to cold is to bundle up, many gardeners assume that plants need to be kept warm in winter. Almost the exact opposite is true. To survive the icy blasts of a Northern winter, plants must be allowed to become accustomed gradually to cooling weather and then, when winter arrives, must be kept cold. The danger to guard against is sudden warmth — a mid winter mild spell, an early February thaw. Mulches, contrary to general belief, don’t protect plants so much from the cold as from the damaging effects of rapidly thawing and freezing soil; this causes frost heaving, which breaks plant roots and exposes them to the frigid air. Similarly, the villain in winterkill and sunscald, two related phenomena, is not cold but the heat of the winter sun.

Winterkill, to which broad-leaved evergreens such as azaleas and rhododendrons are especially susceptible, occurs when the sun’s heat, coupled with wind, removes moisture from leaves faster than the shallow, frozen, almost dormant roots can replace it. Unfortunately, the condition is often invisible until spring, when the leaves turn brown. Sunscald occurs when an unexpectedly hot sun thaws the living cambium tissues just under the thin bark of young trees as well as under that of certain older trees such as beeches, sycamores and fruit trees. Sunscald is a special danger for trees that developed in shade and were then transplanted into direct sunlight. The tissues are simply burned, much as a fair-skinned person gets sunburned when abruptly exposed to too much sun.

Plants that are particularly vulnerable to winterkill or sunscald should be planted where they have natural protection from the sun — against a north wall, for example, or on the shady side of a tall hedge. You can also protect them with a special wrapping tape, available at garden centers, or burlap (pages 24-25) or, in the case of evergreens, by spraying with anti-transpirant compounds, as de scribed on pages 23-24. But the best protection against winter damage is choosing plants that are hardy in your area, planting them in a spot compatible with their needs, and then following a program of plant care that goes on all year long.

- - - -

Bundled up against the January cold, an intrepid gardener cultivates soil around a holly in this 1896 print from La Belle Jardiniêre, a French calendar depicting the activities of a gardening year.

- - --

It’s a truism of gardening, but one that cannot be ignored, that a healthy plant is more likely to get through a tough winter than an unhealthy one. Healthy plants store food more abundantly and harden themselves against winter damage more effectively. Their root systems are also more resilient to the stresses of cold. So prepare your plants for winter by watering them whenever they need it in summer, by giving them adequate fertilizer, and by treating insect and disease problems as soon as you notice them. It’s also vital, and never more so than in winter, for plants to have good drainage. A plant in waterlogged soil may limp through summer, but it won’t survive long after the first frost because the soil heaves when it freezes, breaking the plant’s roots. If you suspect that an area of your garden is poorly drained, till the soil to a depth of at least a foot and mix in builder’s sand or perlite plus compost or leaf mold.

FALL FERTILIZING

As summer wanes, plants need to slow their growth. New tissue is sensitive and fresh green shoots hit by frost will be killed. Plants in general should not be fertilized after midsummer, although in late fall after a hard frost you can ring them with a sprinkling of nitrogen- rich fertilizer such as one labeled 10-6-4. Better yet, top-dress them lightly with an organic substance such as leaf mold, compost or dried manure. The plant’s still-active roots will be fortified for winter by this extra-late feeding. Scratch the material into the ground at the outer edge of the root area, underneath the ends of the branches where the feeder roots are located.

Don’t prune in early fall except to remove dead or diseased branches, because this too stimulates tender new growth. After a hard frost it’s safe to prune, and actually preferable for plants such as maples, beeches and yellowwood that bleed if pruned in spring. Water sparingly in early fall, but once growth has stopped, keep track of the frequency of rainfall. In many areas, late fall is a dry period, and plants should not enter the cold season lacking sufficient water, even if you must provide it.

BEDDING DOWN PERENNIALS

Although many gardeners cut perennials down to ground level in the fall to neaten a flower border, this practice is not always horticulturally necessary. In fact, the appearance of some dried stalks can be quite decorative and some even have seeds that will attract birds. These stalks and stems also serve to hold a mulch in place. On the other hand, many spent stalks are unattractive, like those of day lilies, or are refuges for insects, like the hollow stems of dahlias. These should be removed and discarded. So should any diseased or mildewed stems, so that the plant can start the following year uncontaminated.

Fall is also the best time for lifting and dividing summer- blooming perennials, such as phlox and Shasta daisies, that have become overcrowded. Be sure to set the newly divided plants so their crowns, at the top of the root structure, are level with the soil surface. Firm the soil around the plants, mulch them and soak them every few days if there is no rain.

THE COMPOST PILE

As autumn leaves begin to fall, give some thought to making compost or leaf mold. Both are priceless as mulches or for soil conditioning. To make leaf mold, you can simply dump the leaves into a bin 3 or 4 feet across, made of wire fencing or chicken wire. The leaves will compact in time but you can hasten the process by pressing them down as you dump them and by wetting them with a hose if the surface of the pile begins to dry. In a year or so, nature will have done its work and you will have a dark brown, nutritious, soil-lightening material for your garden. For the compost pile, construct an enclosure at least 2 feet high of wire fencing, wood or concrete blocks. Into it can go not only leaves but dead stalks and other garden refuse. Vegetable garbage from the kitchen, including eggshells, is acceptable as is virtually any biodegradable material.

Perfectionists say the compost will break down and be ready to use more quickly if it’s assembled in layers, alternating a layer of leaves, for instance, with one of kitchen and garden refuse, followed by a thin layer of soil. But since you are unlikely to acquire these substances in such rigid order, you may safely ignore that dictum. You can speed up the pile’s development, however, by turning it over from time to time with a spading fork, by making the top dish- shaped so rain water will collect there, and by adding commercially available chemicals that are specially formulated to speed the decay process. You can also hasten the process by shredding leaves before you add them. Leaf-shredding machines are expensive, but they can be rented. If you adopt all of these speed-up techniques, you may have usable compost in three or four months; if you let nature take its course, your compost will be ready in a year or two.

FORESTALLING WINTERKILL

At some point in fall before the ground freezes, apply an anti-transpirant to your choicest or most vulnerable evergreens, both needled and broad-leaved. Although some gardeners think that these sprays are not worth the trouble and are not very protective — they often wash off in rain or snow — they do slow down the transpiration that causes the loss of moisture and thus go a long way toward preventing winterkill.

= = = =

PROTECTING EVERGREENS

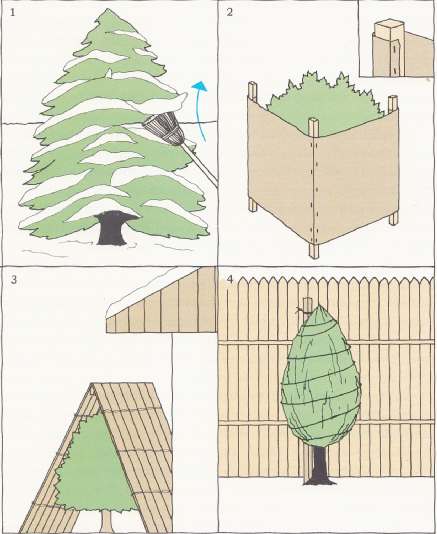

1. To remove light, newly fallen snow from a needled evergreen without damaging its branches, brush gently upward with the flat side of a broom. If the tree or shrub is heavily laden, use the broom handle to poke through the branches and comb off the snow.

2. To protect a broad-leaved evergreen shrub planted in an exposed location, construct a two-sided windbreak of stakes and burlap. Drive three 1-by-1 stakes into the ground, forming a V shape that points into the wind. Wrap a sheet c burlap around the stakes and staple as shown (inset).

3. Evergreen shrubs planted beneath the eaves of a house may need to be shielded from ice and snow that slides off the roof. Cover them with A-frame shields made of snow fencing, boards or sheets of plywood. Hinge the A-frame panels at the top for easy storage.

4. To keep branches of a tall, upright arborvitae or yew from breaking under heavy snow, drive a 1-by-1 stake slightly taller than the plant into the ground beside it. Beginning at the bottom, loosely wind garden twine around both shrub and stake so snow won’t force branches downward.

= = = =

Marketed under various trade names, these antitranspirants come ready-mixed in pressurized spray cans or in concentrated forms to be mixed with water and applied with your own sprayer. They must be applied on a windless day when the temperature is above 40° so the solution will dry properly. Although some manufacturers claim that their brands will last all winter, most antitranspirants eventually wear off and should be reapplied on a mild day in midwinter. Christmas trees or other holiday greens treated with an antitranspirant will hold their needles longer.

Sometimes winter protection needs to be even more substantial. Though burlap-wrapped plants are unsightly, in exposed areas the coat is almost imperative — near the sea, for example, where plants are exposed to the salt spray of winds and winter storms. You can stretch the burlap around stakes driven into the ground beside the plant, or wrap it around the plant and secure it with staples or with nails used as pins. Do this neatly and the results won’t be offensive; otherwise, your shrubs may take on the appearance of a scruffy collection of Snow White’s dwarfs.

ALTERNATIVES TO SALT

Hedges and shrubs along paths and roads may also need extra winter protection from salt, pedestrians and cars. Salt, used to keep sidewalks or streets free of ice, is one of the worst winter enemies of plants — a tree can be fatally injured in a single season if salt is applied frequently nearby. To provide traction on icy walks, use sand, cat litter or gritty urea fertilizer, which benefits plants as it washes into the soil. To prevent stems from being broken, tie them together in a clump or shield them with a snow fence. Tender shrubs like roses have the best chance of surviving deep cold and winter winds if they are both tied and burlaped. Very young or recently transplanted trees should have their trunks wrapped with burlap or a wrapping tape to protect them against sunscald. For good measure, they should also be staked for a year or two after planting so they won’t be blown over. To do this, use heavy wire leading down to stakes in three or four directions around the tree, and be sure to protect the branches and trunk by enclosing the wire in a piece of old garden hose where it loops around the tree.

Wherever there is the probability of large amounts of snow sliding off the roof, it pays to protect foundation plantings with wooden frames that can be set over the plants in winter, and removed in spring. Such frames need not be unsightly. One of the simplest models looks like an A-frame house; it’s made of two panels hinged at the top and thus folds flat for summer storage (left).

One final chore before freezing weather arrives concerns concrete garden pools. A straight-sided pool may be cracked by ice and should either be drained or equipped with a small electric pool heater to keep part of the surface free of ice. You may also have to drain recirculating fountains and waterfalls if you cannot keep the water moving in freezing weather. Never solve this problem with antifreeze if there is any likelihood that animals will drink the water. (Freezing water usually does not damage a pool with sloping sides, since the ice moves upward rather than exerting its pressure against the sides of the pool.)

AN INSULATING BLANKET

With the arrival of temperatures below 32°, it’s time to think about winter mulches. One of the best is, of course, snow. A winter- long snow cover acts like an insulating blanket, preventing wide temperature fluctuations in the soil beneath. This explains why plants in the coldest parts of Minnesota, where snow remains on the ground all winter, have a better chance of coming through unscathed than do plants in New England, where the snow cover, because of frequent sudden thaws, is apt to be intermittent. Soil under snow may freeze only 1 inch deep, while adjacent exposed soil freezes a foot down. Furthermore, in areas where air temperatures fluctuate as much as 30 degrees during cold snaps, a snow cover keeps the temperature of the soil constant.

LIGHT THROUGH THE SNOW

It’s not dark beneath this blanket of snow. Though its consistency is constantly changing, growing denser as it settles, snow is almost always able to transmit a surprising amount of light and air to the plants beneath. A layer of dry, fluffy snow may contain as much as 97 percent air, old granular snow as much as 50 per cent. The light that penetrates a layer of snow enables the plants to carry on the vital process of photosynthesis. This explains the ability of winter-blooming bulbs such as aconites and snowdrops to thrust their shoots through the snow. In fact, melting snow may even act like a fertilizer, carrying valuable nutrients such as nitrates into the soil.

In cold areas where snowfalls are infrequent or irregular, other forms of winter mulch are generally necessary. Bear in mind that these winter mulches, while they may deliver nutrients to the soil as they decompose, are primarily intended to keep the temperature of the soil constant. Consequently, anything that shades the soil from the sun will suffice, from living ground covers to evergreen boughs from a discarded Christmas tree. The mulch must not, however, cut off moisture from the roots of the plant. This excludes the use of certain potential mulches such as peat moss, grass clippings and the leaves of poplar and maple trees, all of which form mats that shed water like shingles on a roof.

THE ORGANIC MULCHES

Wood chips, compost and pine needles are all suitable organic winter mulches but should generally be applied no more than 2 inches thick. If the wood chips are fresh from a tree trimmer’s chipping machine, they may, as they decompose, remove nitrogen- fixing bacteria from the soil; you may have to add supplemental nitrogen fertilizer. The leaves of oak, birch, hickory, beech and linden trees also make good winter mulches. Unlike the leaves of maple and poplar, they curl as they dry and therefore don’t mat when it rains. Salt hay, the marsh grass found near the ocean, is an excellent mulch if available, but ordinary hay usually contains too many weed seeds. Other locally available mulch materials that work well include cocoa-bean hulls, peanut shells, buckwheat hulls and pine or fir bark. Salt hay and leaf mulches do tend to blow around in windy areas and it may be necessary to anchor them with fallen branches or evergreen boughs.

The need for mulches varies with the plant. Native wildflowers and shrubs need scarcely any mulch at all if they are already supplied, as they should be, with a forest-floor environment that is in itself a natural mulch. Other plants such as shallow-rooted camellias, azaleas and rhododendrons need more than the normal amount; this mulch should remain in place year round. But other plants that keep their leaves all winter, such as primroses, hellebores, foxgloves and sweet William, should be mulched lightly so their leaves are not covered. In fact, mulch should never cover the foliage of any plant, but should be tucked beneath the leaves. Keep mulch about an inch away from the main stems to prevent rot.

PROTECTION FOR ROSES

Roses are in a class by themselves. In addition to having their canes tied together in a bundle to prevent breakage, they need to be mulched to a point 8 to 10 inches up the canes north of Zone 7. This protects the delicate bud graft just above the soil level, where the plant was originally propagated. Some rose growers simply pile soil around the canes to this depth, but soil can wash away. It’s safer to construct a foot-high collar of wire mesh, tar paper or plastic around the plant, and to fill the intervening space with leaves, leaf mold or compost. You can also use a splint basket for this purpose, with its bottom cut out. Or you can buy, at many Northern garden-supply stores, a ready-made, tepee-shaped cover made of foam plastic.

In very cold or windy areas, climbing tea roses need even more elaborate treatment to protect their long canes. Untie the canes from their support and bend them over so that they nearly touch the ground, anchoring them with stakes and soft twine. Then cover the entire plant with soil or a mulch of evergreen boughs, salt hay or similar light material. Alternatively, you can dig a trench next to the shrub and tilt the whole plant into the trench for the winter, covering it with light, loose soil.

= = = =

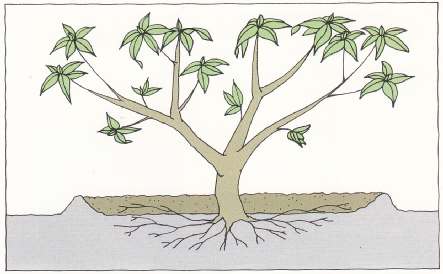

A MULCH FOR ALL SEASONS

Cultivating the soil around azaleas and rhododendrons may damage their shallow roots, so it’s best to keep the soil loose and open with a mulch that is permanent, instead of one that goes on in the winter and comes off in the spring. To confine this year-round covering, mound soil around the plant’s drip line to a depth of 2 or 3 inches, forming a water retaining saucer. Fill this saucer with wood chips, oak leaves, pine needles or other light organic material. Keep the mulch watered well to prevent the roots, which may grow into it, from drying out.

= = = =

DISCOURAGING RODENTS

Roses and other woody plants, as well as some fruit trees, are subjected in winter to a special danger associated with mulches. Mice and rabbits like to make their winter homes in mulch and feed on the tender bark of plants. By winter’s end the animals may have girdled the stem or trunk, cutting off a plant’s food supply and killing it. If you hold off applying mulch until the ground has frozen, you can usually avoid this problem, for the mice and rabbits will have taken up winter quarters elsewhere. Nevertheless, for safety’s sake, you may want to discourage such marauders by installing an 8-inch- high collar of screening around the stems or trunks of favorite plants.

= = = =

SHIELDING AGAINST THE SUN AND WIND

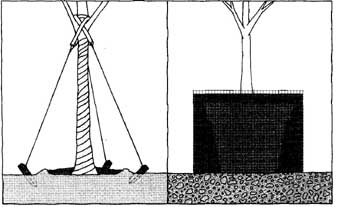

To brace a young tree against wind, sink three equally spaced stakes in the ground and run a guy wire from each stake to a low branch. Thread the wire through rubber hose to protect the bark. Wind tree wrap around the trunk to prevent sunscald.

To winter a hardy deciduous tree growing in a pot outdoors, place around it a ring of hardware cloth 6 inches larger in diameter than the pot and wide enough to extend several inches above its rim. Fill the ring with damp peat moss or shredded bark.

= = = =

One place you are less likely to need a winter mulch is in the vegetable garden, though mulching will prevent rich soil from eroding if the garden is on a slope. Perennial vegetables, such as rhubarb and asparagus, are generally sturdy enough to require little in the way of winter protection beyond a light covering of salt hay or leaves. Before you mulch a food plant, sprinkle compost and perhaps a spoonful of superphosphate around it. This will improve the quality of the crop the following year. Some gardeners turn over the soil of the entire vegetable garden in fall, incorporating the spent plants into the soil to enrich it and getting a head start on spring planting. If you follow this practice, make sure the plants are free of pests and disease.

PLANTS IN CONTAINERS

Although mulching is the standard method of preparing most plants for winter, container plants may require other safeguards.

Mulching just the surface of the soil is of little use, since the roots would still be vulnerable to alternate freezing and thawing temperatures through the sides. A mulch that surrounds the container can insulate the roots of a hardy plant (left). Another effective protection for a hardy container plant is to lift it from its pot and sink it in garden soil over the winter. If it’s impractical to remove the plant from its pot, it may be possible to sink it into the soil, pot and all, depending upon the composition of the container. Clay and terra-cotta pots are impractical, because the freezing soil will crack them. Plastic and metal containers are less likely to crack but they provide little protection against temperature changes. Fiberglass is better in this respect, but the best material is undoubtedly wood. Not only does it protect plants well, but it’s also flexible enough to absorb the stresses of alternately freezing and thawing soil. Styrofoam panels, which can be cut to fit inside the container, keep the soil at a more even temperature.

Of course this protection will vary with the dimensions of the container you use. In general, the larger the container is, the less danger the plant will suffer winter damage. Experienced terrace gardeners agree that any container that is left outdoors all winter should be at least 14 inches deep, and preferably 18 inches. Further more, the thicker its walls, the better: a container made of 2-inch lumber will see your plants through the winter more securely than 1-inch lumber. Be careful to provide good drainage at the base, since soggy soil freezes more quickly than open, porous soil.

ON WINDY TERRACES

If you are gardening on a city terrace, you will also want to make sure that your container-grown plants are protected from winds that funnel between tall buildings. Antitranspirant sprays are useful. You might even want to consider wrapping both plants and containers in burlap. Finally, be prepared on windy terraces to water evergreens even during winter, if neither rain nor snow is copious enough to keep the soil moist.

In the warmer winter gardens of Zones 8-10, where persistent cold is not a problem, mulching will help keep the weeds down and the soil moist, but is of limited usefulness as protection against weather. In these zones, severe sudden frosts, driven by brisk north winds, sometimes strike. Protective mulches do little to allay such conditions. If mulches are applied, they should be loose, light and removable. More practical is some sort of covering that can be placed around the entire plant for a brief period, perhaps just overnight. Some gardeners use burlap, others old bed sheets or light plastic. Whatever the material you use, it should cover the plant but should not touch the leaves. To manage this, support the covering with stakes or some kind of temporary frame. You can heat the enclosure with a single light bulb if the cold snap is expected to be particularly severe. And remember always to remove the covering promptly when the danger is past.

====

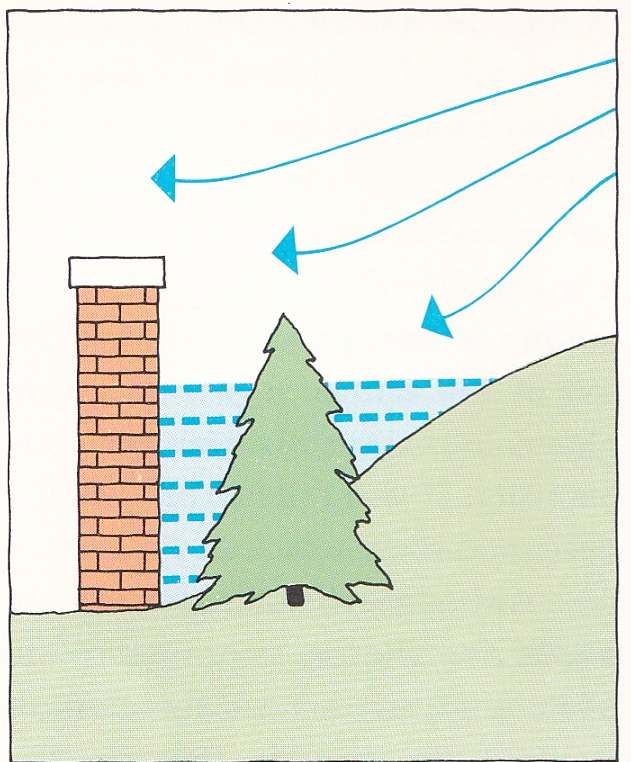

AVOIDING COLD-AIR TRAPS

Cold air naturally drains downhill and will harm tender shrubs or perennials if it’s trapped by a wall or dense hedge or by the close proximity of other plants. To avoid damaging plants of doubtful hardiness, don’t place them near a barrier at the bottom of a slope, and always leave enough space between the plantings at the bottom of a hill to permit cold air to drain through.

====

FENDING OFF FROST

When plants are too large for such protective measures, a constant play of water from a hose or sprinkler may keep frost from forming on the leaves or stems. This should only be done when the temperature is above 32° and rising. If you spray when the tempera ture is falling, you run the risk of adding a layer of ice to the stems, breaking them and injuring the plant. By the same token, an ice-clad plant exposed to the sudden warmth of the morning sun may thaw so rapidly that its flower buds are ruined; winter- or spring-flowering shrubs that are vulnerable to this damage, such as daphnes, rhododendrons, camellias and azaleas, should be planted where they will be shaded in the morning and will thaw gradually. Similarly, all plants benefit from being planted where there is good air circulation — frost collects first in hollows.

As winter runs its course, gardening chores are largely confined to snow removal. Soft accumulations on hedges and broad-leaved evergreens should be gently brushed off as soon as possible. If the snowfall is heavy, it may break stems or branches. Even a light snowfall can cause extensive damage if it turns to ice — and when ice forms on branches, there is not much to do except hope that it melts in time. Don’t attempt to remove the ice, since shaking icy branches does more harm than good. Snow tossed onto shrubbery from passing snowplows should also be removed as soon as possible, since it often contains harmful salt. Be on guard against snow that plummets from your roof onto foundation plantings, perhaps protecting them with the same wooden A-frame structures that are recommended for use in areas of heavy snow.

FROM WINTER TO SPRING

For you and for plants, lengthening days and rising temperatures of late winter signal the approach of spring. Buds begin to swell, stems elongate and the first spring flowers appear. This is the time when you may want to apply a dormant oil spray onto some of your plants, especially woody plants vulnerable to scale attacks later in the year. But withhold this spray until the temperature reaches 40 to 45°. Late winter is also the time to consider removing winter mulches from perennials and spring-flowering bulbs. The question of when — and whether — to do this is a tricky one to answer. Late winter weather can be quixotic, and tender plants need protection until the last frost, especially if young growth has started. On the other hand, leaving the mulch on too long can slow young growth and make it too tender.

To be on the safe side, it’s best to remove a winter mulch from your plants in two stages. When all but the tag end of winter seems to be past—just as new growth first appears— you can remove about half the thickness of the mulch. After three or four days, remove the remainder of the mulch. If possible, do this on a cloudy day so that the newly exposed areas are not exposed too abruptly to the sun. This gradual removal allows your plants to become accustomed to the chilly air without being damaged.

REPLENISHING MULCH

Many plants, of course, don’t need a special mulch for the winter. Instead, the same mulch of compost, wood chips or leaf mold is left in place winter and summer, and is simply replenished when it becomes thin. With shallow-rooted plants that have sent rootlets up into the mulch, disturbing the mulch at any season of the year will do more harm than good.

--- ---

The tranquil beauty of dormant nature

“Gardener, if you listen, listen well: plant for your winter pleasure, when the months dishearten,” wrote the English gardener and essayist Vita Sackville-West. But such planting requires careful thought and much imagination. The winter garden, bereft of flowers, relies more on shape and texture than on color. It draws upon nature’s bare essentials, and on the arrangement of these essentials. A silver-barked birch tree is played against a backdrop of ever greens; a tall, narrow juniper is set amid a circle of smaller rounded ones. When color does surface, it’s subdued, often a mere pinprick in the prevailing palette of grays, greens and browns.

Evergreens form the backbone of a winter landscape, and are arranged to highlight their contrasting shapes and sizes, from the ground-hugging Wilton carpet juniper to the tall, shaggy Hinoki false cypress. Their leaves, whether needled or broad, come in a variety of shades of green and often reach beyond to gold, red, copper or silver gray. Some, like variegated Japanese aucuba, have beautiful two-toned leaves. Still others, like wintergreen and English holly, display bright, decorative berries.

The herbaceous perennials can also play a role in a winter landscape. With the advent of frost, ornamental grasses turn warm shades of tan and the dense flower heads of many sedums darken to rich hues of brown and red. Coneflowers retain their chocolate- brown centers while the crisp green leaves of sweet woodruff soften to gold. Left untouched, these plants rise from the snow-crusted ground like natural dried arrangements.

On a larger scale, so do the bare branches of deciduous trees and shrubs. After their leaves have fallen, they reveal the beauty of their forms — round, conical, columnar, weeping or spreading — and many have added beauty when colorful bark is exposed. The paper-bark cherry tree’s trunk is a shiny, almost metallic-looking red; the stems of the Siberian dogwood fan out in sprays of scarlet. Lacy twigs and decorative bark, set against a contrasting wall or a dark background of evergreens, create a study in stark contrasts.

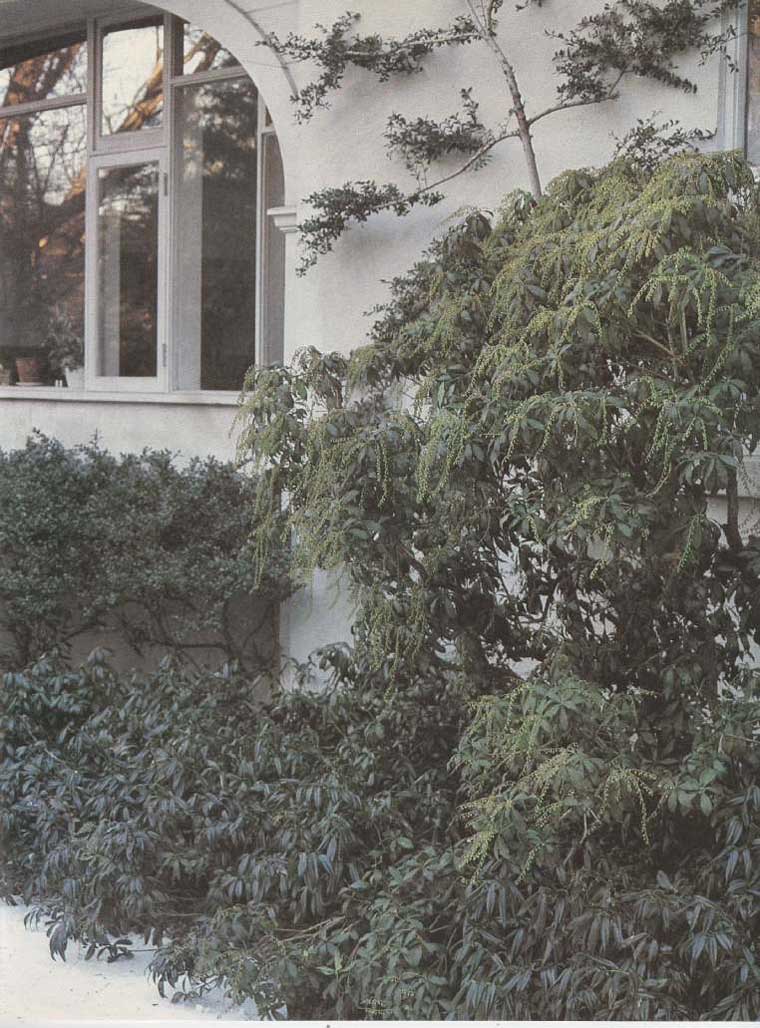

Japanese holly, sarcococca and a Japanese andromeda (left to right) combine to sculpt a wintry entrance wall with a has-relief of evergreen. A second holly is espaliered above.

- - -

The ever-useful evergreens

Plants whose leaves stay green year round come into their own in winter when their color dominates the landscape. Among them are the two large classes of evergreens: those with needle-like foliage, such as pines and junipers, and the broad-leaved plants, such as rhododendron and holly. Both groups contribute interest to a winter garden either as accents or as backdrops for deciduous plants.

But the green that graces a winter garden can come from sources other than trees and shrubs. Ivy can cloak a fence or a wall, a host of low-growing ground covers can carpet the frozen soil, and the winter-hardy leaves of succulents like the yuccas opposite can punctuate a frigid landscape with shapes that are dainty or bold.

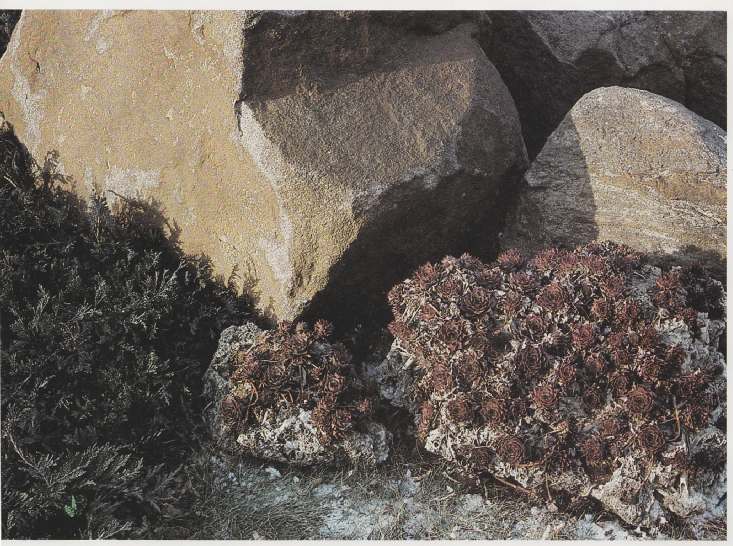

The silver-tipped leaves of a blue carpet juniper and the reddish-brown rosettes of a common houseleek sparkle under a shaft of winter sunlight. The plants are set among rocks whose surfaces hold and radiate heat.

The sword-shaped leaves of yucca, weighted down with snow, cascade over a winter garden like frozen fountains.

Their gray-green color sets off the golden clumps of calamagrostis grass in the background.

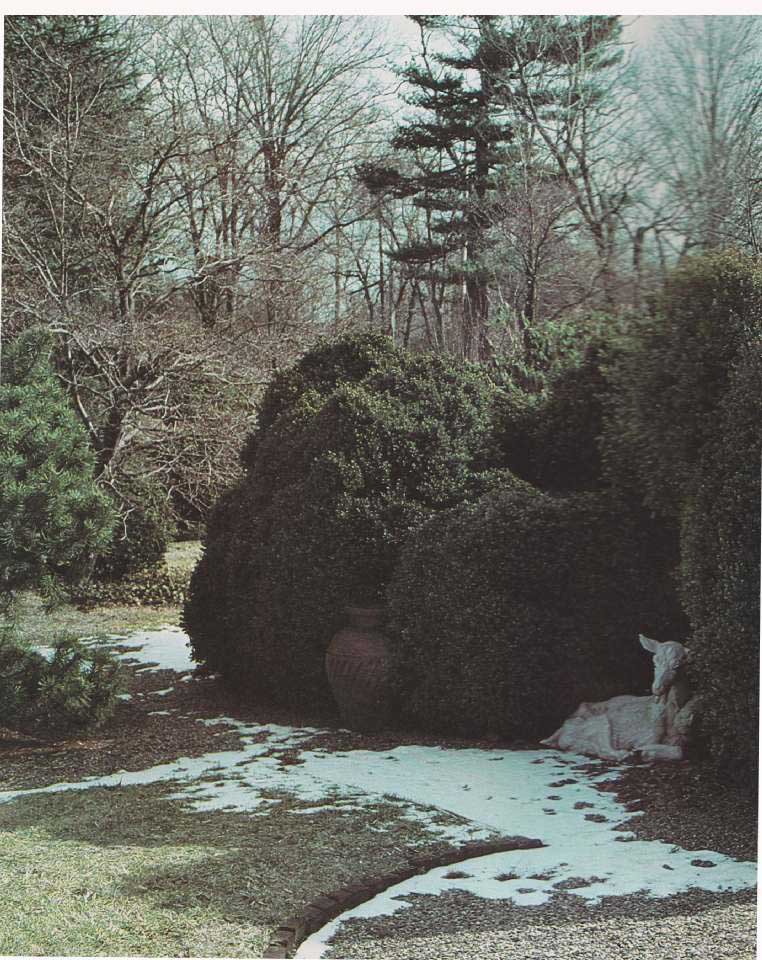

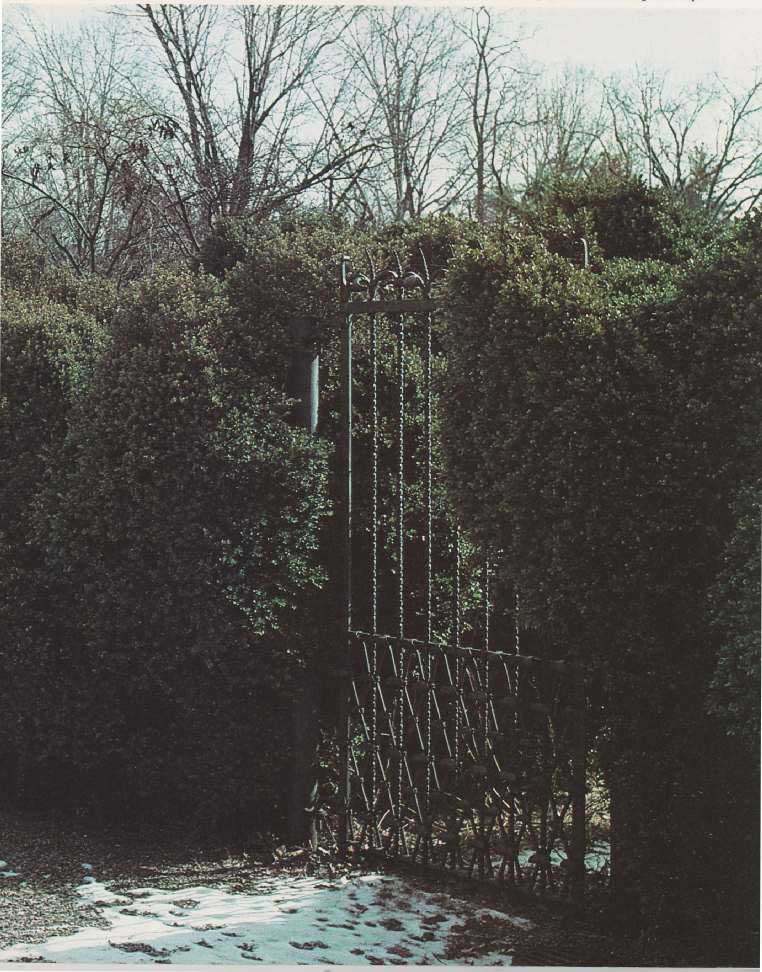

A decades-old boxwood hedge, sculptured by nature into strong undulating shapes, wraps a winter garden in privacy and shelters an urn and a terra-cotta goat. Deciduous trees, including a gray-barked kousa dogwood (left), provide a contrasting backdrop.

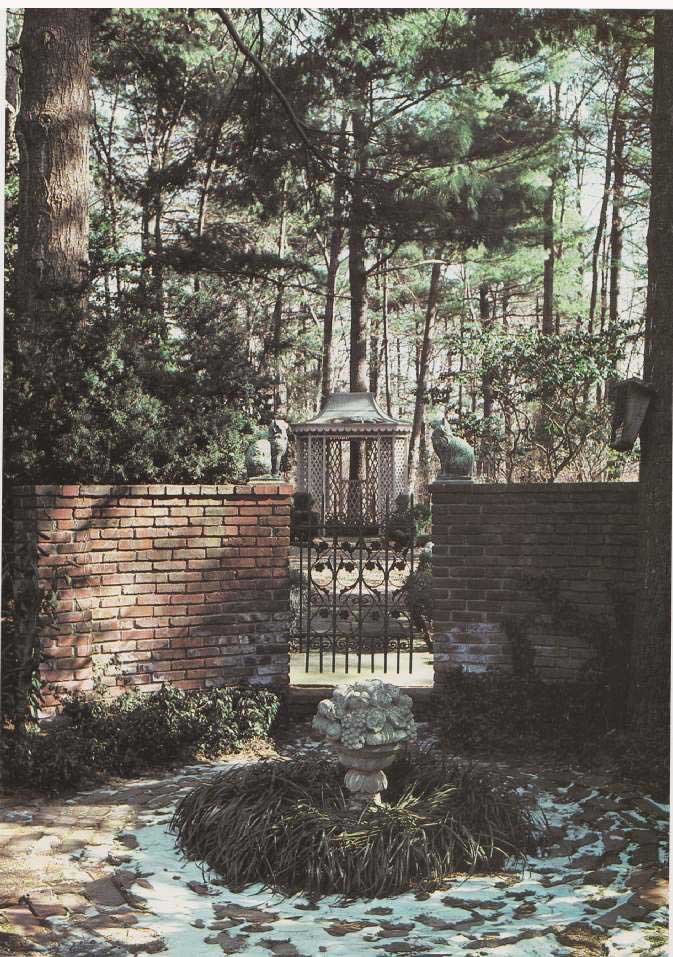

A circle of evergreen lily-turf and the upright branches of a Japanese yew (left) echo the architectural lines of a formal garden.

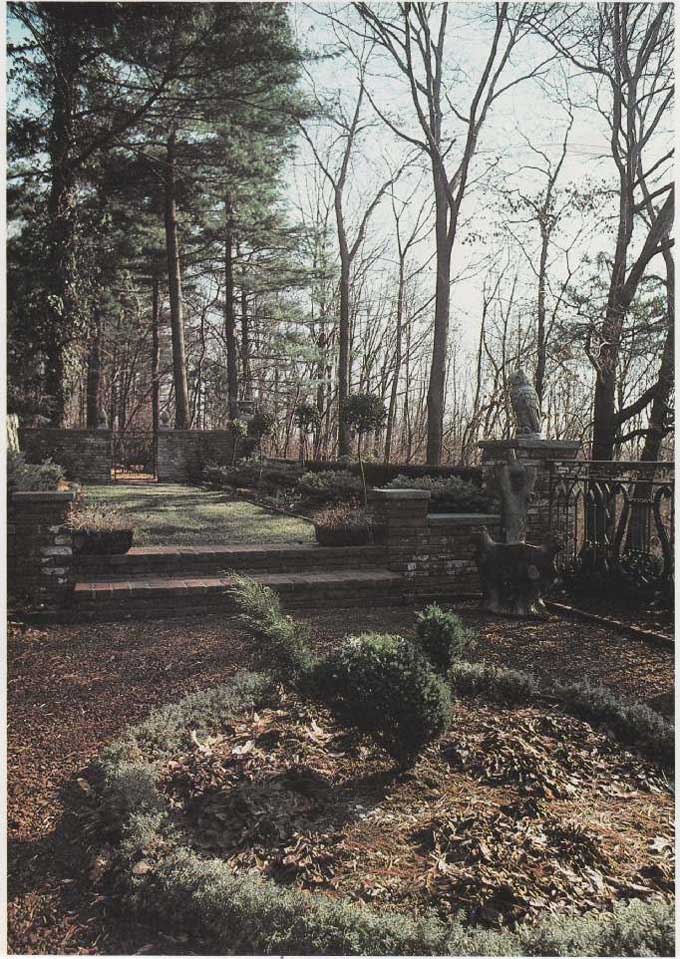

Topiary evergreens, including a Chinese-juniper bird in a ring of lavender cotton, demarcate pathways of this formal garden.

- - - -

Focusing on form

Deciduous trees and shrubs, stripped of their leaves in winter, reveal the beauty of their bare bones. Shapes, outlines, bark textures and colors hidden or overlooked in summer suddenly come into sharp focus: the fantastically twisted branches of a curly hazelnut shrub, the silver tracery of beech-tree branches, the deeply ridged bark of an Amur cork tree. Complementing them in a snowy landscape are deciduous vines, whose intertwined stems enhance garden structures in winter as much as in summer.

(missing pages 41-42 – Google images per description)

A century-old European beech tree spreads its fanlike form against a blue winter sky. Its smooth, silver-gray bark is clearly visible only in winter; during the rest of the year it’s hidden under a thick veil of leaves.

A wisteria vine, its trunk twisted with age, crowns a gazebo like a giant bird’s nest, Supporting it are the posts of old gas lamps set in concrete. In late fall and early winter, stems that no longer flower are pruned away.

The slender gray trunks of a stand of quaking aspens, mottled with green moss, are as beautiful in winter as in summer. These native trees of the Pacific Northwest are valued for their resiliency in strong winter winds as well as for their decorative bark.

Articles in this Guide are based on now-classic Time-Life Encyclopedia of Gardening Series from the 1970s ... a timeless series, some titles of which are still available in libraries and bookstores... see our Amazon Store for purchasing options.