AMAZON multi-meters discounts AMAZON oscilloscope discounts

This section describes approaches and alternatives for developing a stores-control system for the maintenance group that will help provide an optimum level of maintenance service in a cost-effective manner. In the first section, the important elements concerning the types of and the selection of stores and the storage of maintenance material are described. The second section discusses the principles and procedures of stores (inventory) control.

INTRODUCTION

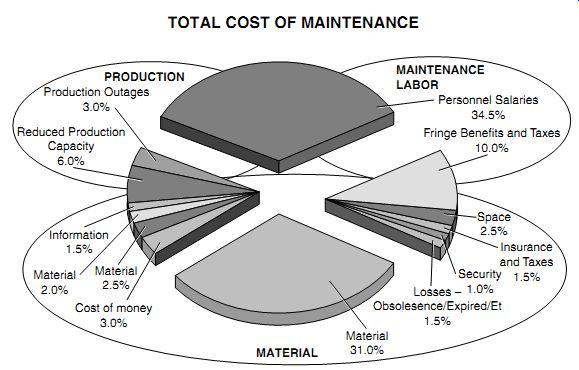

Maintenance costs can generally be grouped into three generalized areas, each of which includes several specific areas (see Fig. 1).

_ Costs associated with maintenance labor

_ Costs of required material and spare parts

_ Costs of production downtime when breakdowns occur

Typically, the cost of maintenance material and spare parts can be in the same dollar range as the cost of maintenance labor. In order to control maintenance material and spare parts cost, necessary stores and hardware must be purchased carefully. Having too much material on hand increases inventory carrying costs and leads to definite losses. Not having enough material on hand or readily avail able will increase both maintenance labor costs and the cost of production downtime.

FIGURE 1 Maintenance costs.

MAINTENANCE STORES AND MATERIAL STORAGE

Maintenance Stores Components

Material stored in maintenance storerooms can be grouped into five categories:

1. Major Spares (Spare Parts). These are the "insurance" items that are stocked for specific plant equipment to guard against prolonged equipment downtime. It is not uncommon for about half the dollar value of maintenance stores material to be made up of spare parts. The items in this category are:

_ High cost, when compared with the cost of other stock items

_ Entire assemblies/subassemblies for "vendor only" repairable items

_ Specialized for use on one or a limited number of equipment items

_ May be difficult to obtain promptly from suppliers

_ Likely to have longer average turnover intervals than other stock items

_ Used in equipment for which prolonged downtime is considered costly or unsafe

Compared with the relative certainty of normal stock usage, the need for major spares or spare parts is somewhat of a gamble. They should be stocked only when the risks involved in doing without them are considered to outweigh the total cost of carrying them in stock for a predicted interval or where lead time for obtaining them can jeopardize production for extended periods. Examples include special bearings or cams, special motors, gear replacements, single-purpose electronic components, and any special-order items for which there is no redundancy. The predicted usage interval may be a matter of judgment, based on past experience with similar equipment, or repair records may show with greater certainty some of the failures that are likely to occur in the future.

2. Normal Maintenance Stock. These are items, which generally have less specialized usage, more definite replacement requirements, and shorter stock-turnover intervals than spare parts. Normal maintenance stock includes items such as pipe fittings and standard valves, commonly used bearings, bar stock for machining, motor/generator brushes, electric wire and switches, lumber and plywood, bolts, welding rod, and electrical conduit. The decisions that must be made concerning what to stock, how much to stock and when to reorder can be handled in a more routine manner than with spare parts.

Applicable procedures will be discussed later in this section.

3. Janitor/Housekeeping Supplies and Consumables. This category includes paper towels, cleaning compounds, and toilet tissue, which are commonly a part of the maintenance stores. It also includes the plant's various consumables such as lubricants, nominal lighting components (bulbs, ballasts, fixtures, etc.) for failure replacement (complete relamping/lighting inspections should be scheduled events for which supplies are ordered only as scheduled), filters, seals, gaskets and O rings, and other consumable items unique to plant equipment and not commonly replaced by operators. Because of their closely predictable usage and different handling requirements, they may be classified and controlled separately.

Many of these items may have limited shelf lives. This aspect will be discussed later in this section.

4. Tools and Instruments. In small- to medium-sized maintenance departments, it is common practice to require that the maintenance storeroom handle and control the special-purpose tools and test instruments (e.g., VOM meters) that are issued on a loan basis. While this is not the same as the material-control function, it is a practical possibility and justifies attention in developing the overall storeroom plan.

5. Nonmaintenance Items. A large maintenance storeroom might be expected to stock some of the supplies required by production departments but not classified as consumable material. This could be a relatively minor function. The opposite situation could also occur, as in a job-shop manufacturing plant which required the use of a wide range of pipe fittings, electrical and wiring supplies, steel plate, sheet metal, lumber, etc. It is probable that many of the items normally stocked in such a plant for use by manufacturing sections would be the same as those needed regularly by the maintenance crafts. If so, the maintenance men might be required to use the manufacturing storerooms for some of their material needs. There are disadvantages in such combined stores functions as well as obvious advantages. This situation will be discussed in more detail later in this section.

Conditions Tending to Increase Maintenance Stores Inventory

As previously noted, development of sound stores-control procedures requires analysis of a number of factors that have an effect on total maintenance costs. The costs of carrying specific inventory quantities (such as special gears) must be balanced against anticipated costs of such material not being readily available. It is important to recognize all the cost factors involved so that this balancing act can be performed in a sound manner. This section discusses some of the conditions that tend to increase the amount of stock carried within the various maintenance storage areas.

Cost of Production Downtime. When equipment failures occur and production is slowed or halted because equipment repairs are delayed due to lack of spare parts or materials, the resulting losses can be serious. This is particularly true if required capacity is affected or if production operators cannot be reassigned to other work. A systematic and detailed record of equipment downtime throughout the plant should be maintained in order to enable realistic evaluation of policy.

Maintenance Scheduling. An important factor in effective control of maintenance costs is the systematic planning and scheduling of maintenance jobs. This can ensure a full day's work for each man, avoid assignments when equipment is not ready, reduce waiting among various crafts on the same job, ensure proper crew sizes, and obtain other results that combine to reduce costs. One of the keys to maintenance planning and scheduling is to have normal stock items on hand without needing to check the availability of every minor item. Maintenance scheduling quickly bogs down and maintenance costs can rapidly escalate if more than a few special items have to be separately ordered and accounted for ahead of scheduling or during progress of the job.

Quantity Purchasing. The fact that many items cost less when bought in large quantities is one of the influences toward an increase in inventory. A similar influence comes from the cost of issuing a purchase order, checking receipts, and making payment. Quantity purchasing can often result in total cost reduction but only if the savings are greater than the added costs incurred by carrying the inventory over the increased period of time.

Equipment, Parts, and Material Standardization. When a plant has different makes and models of motors or pumps that have approximately the same performance specifications; has different electric controls which do the same thing; has various solenoid valves or electric relays with essentially the same functional properties; or has an unnecessarily wide range of sizes or grades of materials such as lumber, sheet metal, steel plate, or welding rod utilized in a plant, maintenance stores inventories can become excessively large. When plant expansion occurs, the economics of upgrading existing equipment at the same time, in order to enhance standardization, should be thoroughly evaluated. While standardization of maintenance parts and materials will always be less than desired, there are ways to improve standardization. Some of these approaches will be discussed later in this section.

Multiple Storage Locations/Depots. With decentralized maintenance storerooms, duplication of stock is likely to exist. This may not be serious in the case of craft supplies that are stored at a single location for each craft, since materials used by any one craft are somewhat specialized. The duplication becomes more pronounced, however, with area storerooms that carry maintenance sup plies for various crafts. The effect on inventories in such cases is equivalent to that of the lack of parts standardization.

Order and Inventory Quantities. Without records of inventory quantities, casual inspection at irregular intervals is usually relied on to determine when orders should be placed. In such cases it is easy to order more parts than needed just to be on the safe side. The same tendency occurs when reordering without the aid of predetermined order quantities. Although these simpler approaches may eliminate some clerical time, they do not provide the degree of control that can be attained with a more orderly system of records.

Supplier Location and Dependability. Many plants are close enough to supply houses for rush orders of certain items to be picked up or delivered in about an hour when emergencies arise.

Similarly, some of the suppliers of specialized spare parts, even though not located near the plant, can be depended on to furnish parts from their own stock without delay. If you rely on a supply house to furnish selected stores on a same- or next-day basis, the supply house must be made aware of this so it continues to stock those items. When such conditions do not exist, there may be valid reasons to consider increasing selected stock inventories.

Production Facilities Characteristics. Justifiable maintenance stock inventories are obviously increased when conditions such as the following exist:

_ Large investment in plant equipment or facilities

_ Process equipment used continuously as in the case of refineries, steel mills, or power plants

_ Production equipment must have a high "on-line" factor as in highly automated facilities, convey or-fed assembly lines, or bottleneck facilities

_ Old or worn equipment must remain in use to handle production needs

_ Lack of spare or redundant facilities

Outside Contracting. Plant policies vary widely in this respect. Large jobs occur at frequent intervals in many plants. If the regular maintenance crews normally handle such work, then stock quantities are likely to be set somewhat higher to avoid stock-outs that may affect rush jobs.

Conditions Tending to Reduce Maintenance Stores Inventory Availability of Cash. Most plants have a backlog of possible purchases (new tooling, machines, or equipment) that will reduce costs through resulting methods improvements. If the cutoff point for such investments is, say, a 20 percent annual return, the money invested in carrying marginal stores inventories should be expected to pay off at about the same rate, after deducting expected costs. It is admittedly difficult to estimate the probable return in specific cases where decisions are required about inventories. This line of thinking is a sound one to follow as a policy guide, however.

Storeroom-Associated Cost. Some of the expected storeroom costs are listed as follows:

_ Plant space occupied by the storeroom and utilities.

_ Required storeroom attendants, purchasing clerks, material handlers, and security personnel.

_ Storeroom facilities involved (bins, cranes, fork trucks, etc.).

_ Information technology (hardware, software and administrator costs).

_ Obsolescence of stored parts. As new technology or old age causes replacement of specific plant equipment, the spare parts for specialized use on such equipment become obsolete.

_ Depreciation and depletion of stock material. Handling within the storeroom may cause damage to fragile parts. Some items have a limited shelf life. There will be occasional misuse of expensive parts. Stealing can be a problem, particularly where there is ready access to stored material or where inventory records are controlled by stores attendants.

_ Insurance and any applicable taxes.

Supplier Reliability. This acts to reduce maintenance stock needs, as previously discussed. While there is normally an added cost from buying and delivering in small quantities, this can in some cases be reduced greatly through "systems contracting" techniques, which is discussed later in the section.

Production Scenarios. Some process plants are equipped with spare or redundant equipment to take care of repair needs. Capacity requirements for a particular plant or section of the plant may be such that some equipment downtime is unimportant. New production facilities may require little replacement of parts for a number of years. Such conditions will obviously act to reduce needed repair parts inventory.

Centralized Maintenance Storerooms

A basic step in establishing control procedures is to decide whether the various categories of material should be (1) stocked centrally in one location, (2) stocked in various decentralized maintenance storerooms, (3) stocked with supplies for production departments, or (4) handled by some combination of these approaches. To make this decision properly for a specific case involves considering a number of factors. The possible advantages to be gained from centralized storerooms are listed here.

Duplication Avoided. While a single store location does not in itself assure minimum inventories, it does provide the basis for controls that will keep total stock at a minimum. This is not the case when specific items are stocked in more than one storeroom location.

Level of Inventory Control. Workable control systems involve requisitions, inventory records, and other procedures that will be covered later in this section. Accurate, conscientious clerical work is required. This can seldom be achieved without one or more storeroom attendants plus interested supervision. Small sub-storerooms make it more difficult to justify the kind of staff that will apply controls to achieve desired results.

This is particularly true for second-shift work. Only the largest maintenance functions could justify assigning second-shift attendants within various local area storerooms. Yet a second-shift man might properly be used in a centralized storeroom for a medium-sized maintenance department.

Personnel Requirements. It takes less work to disburse the stock and control the stock quantities for a central supply of, for example, various pipe fittings than to do so for identical fittings in several different areas. This would be true even if the total number of withdrawals were the same in each case. While attendants may not be used in decentralized storerooms, there is an equivalent handling time on the part of craftsmen or maintenance foremen. With good supervision, a centralized store room can be operated more economically.

The rush and slack periods for obtaining maintenance material are generally quite consistent within a plant. After identifying these periods, it is often practical to transfer a clerk from some other work temporarily to help fill stores requests, say for two separate hourly periods each day. This is one of the many ways that overall costs can be lowered through a centralized stores function.

On the assumption that there will be better supervision and more orderly handling within a central storeroom, the losses that occur from depreciation and depletion of stock would normally be less than for subdivided stores. A higher stock turnover rate could be expected.

Delivery Capability. One way to avoid the need for maintenance men to walk to a storeroom and wait there for service is to make frequent deliveries from telephoned requests. This service is justified and easier to provide if the storeroom is a large one with frequent calls for stock.

One practical way of establishing the delivery service is to select and identify a number of delivery points in the plant area and set up a truck route that contacts these points at intervals such as every half hour. Telephone calls to the storeroom would then be filled promptly and placed at a dock for truck pickup and subsequent delivery. Requisitions could be signed or collected as deliveries are made.

Cost Accounting Reliability. Small storerooms tend to operate without a regular attendant on all working shifts; therefore, the larger storeroom, due to the presence of an attendant on all shifts, tends to provide better control of cost allocation for material that is issued. This is not automatic with size, of course, but requires close supervision and careful handling. The following storeroom functions should be in place:

_ Consistent use of material requisitions

_ Regular checks to see that requisitions show the proper account charge and have been approved in the manner designated

_ Enforcement of rules to permit only the attendants or other designated individuals within the store room

_ Proper accounting for receipt and disbursement of salvaged or returned items

_ Transmittal of all requisitions to the accounting department for prescribed handling

Space Usage Efficiency. This advantage would hold in comparing centralized stores with sub storerooms that have overlapping stock items.

Large Job Planning. For large repair, construction, or rearrangement jobs to be performed by plant maintenance crews, good advance planning may require setting aside or staging certain amounts of stock items to be sure they are available when needed. This is easier to accomplish in an orderly manner when there is one central maintenance storeroom rather than several small ones.

Handling and Receiving. The receiving point and receiving inspection may be where production materials are received or at the central maintenance storeroom. In both cases, the latter in particular, handling is reduced when only one maintenance stores location is involved.

Advantages of Decentralized Maintenance Storerooms

There are two general approaches to decentralization. One is to locate all or a portion of a specific craft's specialized stores and material at or near the shop location of the craft involved. The other approach is to locate spare parts and/or material within specific plant areas for convenience to the point of usage. It is also feasible to employ combinations of these approaches. It is not possible here to discuss individually all the variations. Consequently, the advantages of decentralization noted below may apply in some cases and not in others.

Less Walking and Waiting Time for Craftsmen. This is an obvious advantage and is perhaps the primary reason for area storerooms. In considering this advantage over centralization, however, the possibility of material delivery should be kept in mind, as previously noted. With an hour's advance planning of material needs, it may be easier for maintenance men to get material from a central store room than from the nearest area storeroom.

Closer Control by Craftsmen Concerned. This occurs where material is turned over to craft departments for handling by the maintenance men concerned. If there are both close supervision and responsible maintenance craftsmen, this can work out well, though not without losing some of the advantages listed for central storerooms. Examples that have been observed to function satisfactorily are:

_ A welding- and burning-torch repair station in a large plant where the assigned maintenance man controls all the repair parts involved

_ A fork-truck repair station in a medium-sized plant where parts used by the assigned mechanic are stocked and handled in an orderly manner

_ A repair station for small tools where the boiler-room attendant makes such repairs at intervals and stocks the necessary parts

Closer Control by Supervision Concerned. This may apply when spare parts are stored at the point where they will eventually be used. In such cases, the line management involved can see what is available and presumably can be held more closely accountable for downtime due to waiting for spare parts. It should be recognized, however, that central storeroom procedures could include regular reviews by line management of repair parts stocked for their departments.

A similar situation can occur in the case of separate maintenance storerooms that are located next to decentralized maintenance shops. Craft foremen involved can supervise the handling of stock material more closely, but this requires time on their part and is not necessarily an advantage.

The Correct Material. When maintenance men regularly inspect and handle the stored material themselves, they have the advantage of being able to select the most suitable items for conditions at hand. This advantage may be counteracted, however, by the resulting interference with precise record keeping or by waste from poor handling practices.

For example, a large research laboratory provides several decentralized storerooms and allows maintenance men and technicians to have access to many items so that they can determine by inspection what will fit their needs. The same laboratory has centralized storerooms, however, to which only the attendants have access. The items stored here are of greater value or are subject to pilfering. The cutting of metal plate and bar stock, micarta, plastic, etc., is also handled on a central basis since this requires special handling and would involve undue waste without regular operators being used.

Factors Involved in Combined Storerooms

As previously mentioned, one of the possible approaches is to stock part of or all the maintenance supplies within production storerooms.

Advantages. To the extent that this is done, there is obviously less duplication of parts. It permits use of the same inventory control procedures and tends to reduce the number of stores attendants needed.

Disadvantages. Chances are that storerooms, which issue parts or material to both production and maintenance personnel, will be located for the convenience of the production departments. The result is likely to be a scattering of some maintenance supplies all over the plant. There could be time lost from excessive travel to get material in such cases.

Another disadvantage is that the stores inventory control procedures will normally be oriented in the direction of production requirements and may not closely fit maintenance needs without some alterations. If it is found that such combinations of stores functions are advisable from an overall standpoint, steps should be taken so that adequate service is provided for the maintenance department.

Organization for Maintenance Stores Control

In the past, there have been at least three different organizational concepts regarding maintenance stores control. One of these recognizes the need for sound purchasing by placing the storeroom personnel and material-control procedures within the organization of the purchasing department. A second approach stresses cost accounting and safeguarding of the investment within the storeroom by delegating the organizational control to the accounting department. The third approach recognizes the importance of material control in providing a sound basis for adequate maintenance service by placing the storeroom function within the plant maintenance organization.

The last of these three organizational concepts is a sound approach that can be applied while retaining the needed assistance and control from other departments. Typical procedures would include buying material through the purchasing department and developing inventory records through the accounting department. The plant maintenance manager would normally retain the authority to select the items and quantities to be stocked (within policy limitations) and to ensure adequate storeroom service through supervision of storeroom personnel.

PRINCIPLES OF MAINTENANCE STORES CONTROL

The principles for systematic control of maintenance stores are listed under headings that follow. As in all cases of maintenance control, it is the total cost figure that should be considered. Controlling spare-parts cost, for example, might include demonstrating the need for adding to such stock in specific cases in order to reduce the costs of equipment downtime.

Documentation

The need for accurate and comprehensive documentation is an obvious one, yet many plants do not make full use of the information contained in stores documentation. This is the primary source of information for decision making with regard to inventory control. All plants, regardless of size, should utilize some form of automated information management. Even the smallest operations can establish effective controls with a single personal computer and off-the-shelf software for less than $1000.

The range of system structure for an information management system can go from the single personal computer to a customized, totally integrated computerized maintenance management system (CMMS) that has several modules including a planned and preventive maintenance system, maintenance planning/scheduling, and stores and inventory control. Hardware architecture can be expanded to provide terminals at the maintenance-shop level where the individual crafts can enter and submit stores/spares requisition information to their supervisor for approval and subsequent auto-routing to the storeroom for issue. Software is available that can connect, not only to your corporate Intranet, but also to the global Internet to integrate automated purchasing with your inventory control system.

With the advent of and improvements in information management software, the vital statistics contained in your documentation can not only be formatted in a multitude of decision-aiding compilations, they can also be analyzed by the software itself which can then provide recommendations regarding economic inventory control.

The Stores Requisition. This is considered an essential step in withdrawing most material from the maintenance storeroom because it provides:

_ Authority for stores attendants to issue stock

_ A basis for a maintenance man to obtain approval at the designated level to withdraw stock (usually his maintenance foreman)

_ A systematic basis for cost accounting and inventory records

_ A means of reducing mistakes or lost time by stores attendants

The requisition format should be as simple as possible. One copy will normally suffice; with computer information management, a completely paperless system is also possible since this end of inventory control is entirely internal. Minimum required data includes:

_ Equipment application

_ Material description and quantity

_ Material code number (a vital element discussed in the next section of this section)

_ Account charge number and/or work-order number

_ Date, user's name, and approval space

The high cost of many repair parts or normal stock items justifies a careful check of material used on specific jobs. It may be practical to repair existing parts, use salvaged parts, use less expensive material, or use different material that is better for the job. For these reasons, it is sound practice to require that maintenance men obtain their foreman's approval before withdrawing material.

Because of the lost time that is often involved in locating a busy foreman within a large plant, some compromise with this approach may be necessary. A substitute control plan is to issue material for requisitions signed by maintenance men, collect all requisitions during the shift, and have them signed by the respective foremen later as evidence that they are familiar with the withdrawal and approve use of the material as specified. A wireless system employing a pager function as well as remote network access for rapid approval is also available for those operations large enough to justify the costs of this technology.

The Inventory Record. Most control procedures make use of a continuous or perpetual inventory record on which receipts are added and withdrawals subtracted. This may be done through:

_ Hand posting to a form having columns for date, order reference number, receipts, issues, and balance on hand. Such a procedure is simple and relatively inexpensive to install. This method is only effective for the smallest operations where the information management system does not include inventory records or automated inventory updates.

_ Machine posting, using standard bookkeeping machines. The machine does both the computations and printing of the inventory record. This helps reduce errors, which may occur with hand posting, but again is suitable only for smaller operations without the necessary information management system capabilities.

_ Electronic data processing. The input is usually in the form of operator entry from requisition forms for each transaction. In integrated systems the data from the requisition automatically updates the inventory record as the requisition is filled. The requisition information is applied automatically to update the records of quantity and other details, which are part of the data-processing system. An advantage of this method is that various other forms of output data can easily be obtained as a by-product. Examples are total material cost on individual work orders, dollar value of spare parts or normal stock inventory, and a listing of items for which the inventory quantity has reached a specified level.

Documents required for maintaining the inventory records may come from the storerooms, the receiving department, the purchasing department, or other sources. Some organizations require the stores attendants to maintain the inventory records during slack periods, but this has undesirable aspects. More reliable control comes when the material inventory record function is separate from the storekeeping activities. Reasons are fewer opportunities for false record keeping to cover up shortages, and increased clerical reliability. Where it is particularly important to minimize inventory errors, stock balances may be recorded both within the storeroom and, later, through electronic data-processing methods.

Often, there are many parts held in storage (or just lying around) that don't belong to any equipment in the facility. This happens slowly, over time. Equipment in the facility may be retired or no longer at the site, but the parts for that equipment may still be on the storeroom shelves. In other cases, someone may have ordered and/or received the wrong part but didn't return it.

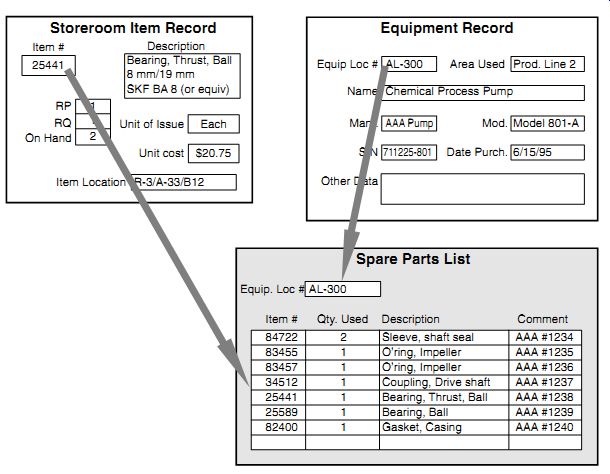

The ideal way to ensure that the parts in your inventory are the parts that you need is to connect all the parts you store to equipment in the facility. One way to do this is to add related equipment data to the stores item description. This is less than optimal because an identical item may be used on different equipment of various manufacturers or models.

A better solution is contained in almost all CMMS. An often unused feature of CMMS is the ability to tie an inventory item to an asset or location record through the use of a third record called the spare parts list or bill of material (BOM). The thrust bearing in the storeroom item record is generic and can be used in many types of equipment. In this example, it is used in a chemical process pump. Both the pump and the bearing are related to the spare parts list by the equipment location number and the item number, respectively.

FIGURE 2 Spare parts list.

Physical Inventory. A physical inventory of stored material is essential at periodic intervals to detect errors in the continuous inventory records. This also serves as an indication of possible stock depletion. If there are serious, unexplained shortages, the need for corrective action is indicated.

Annual physical counts are common, with more frequent checks if conditions dictate.

The physical inventory may be conducted over one single time period, such as when the plant is shut down for vacation or over a weekend. This will require a crew large enough to complete the job in a few days. An alternate method is to make provisions for a continuous inventory to be conducted throughout the year on a part-time basis. Using this approach, the checking of various items would be scheduled so that all are covered within a designated interval.

Decision Making

Deciding What to Stock. When the plant is new, it will be necessary to determine what material should be stocked. The recommendations of equipment manufacturers should be reviewed concerning spare-parts needs but not followed blindly. The past experience of craft foremen will assist in the selection of normal stock material. Decisions made along this line should be on a conservative basis: usage records will provide a more definite picture in the future.

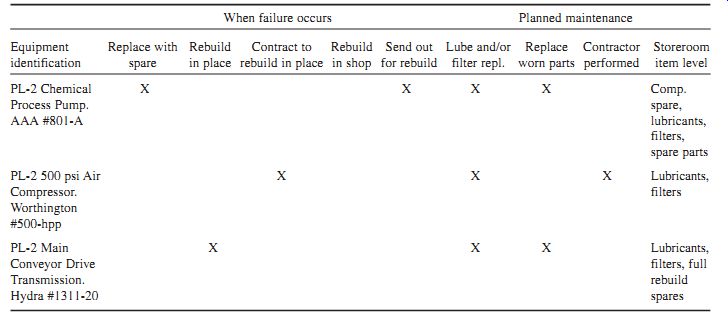

It is not a good idea to build a spare-parts list for every piece of equipment in a facility. For example, stocking all the spare parts required to rebuild an air compressor is worthless if facility maintenance workers don't have the skills to do the work or if an outside service organization will be contracted to perform the rebuild. However, parts required for preventive maintenance or simple repair (such as lubrication, filter replacement, spare motor or spare coupling replacement), should be stocked. The usual high cost of spare parts plus the judgment involved in deciding whether to stock them or take the risk of downtime indicates that a suitable management level should be specified to authorize stocking such parts. Typically, the maintenance manager would be expected to screen all such requests. Approval of production management where the equipment is located might properly be required also before spare parts are classified as regular stock items.

By listing facility equipment and identifying the level of maintenance to be performed, decisions on spare-parts requirements can be much more methodical and accurate. A table, similar to Table 1, can be used to facilitate this step.

TABLE 1 Facility equipment and level of maintenance.

Order Points. These are numerical values that should be established through analysis of the anticipated usage rate plus the time required to obtain delivery of additional material. When an order point or stock level is reached on the inventory record, a new order should be initiated. If desired, an additional, somewhat lower stock quantity (minimum) can be designated as the point at which urgent checking should be initiated to expedite delivery. The order points should take into consideration peak usage requirements, as shown by past records. They are subject to periodic revision as conditions change.

Order Quantities. The stock quantities to be recorded when a low point is reached should be developed through an analysis of factors such as:

_ Average usage quantity, determined from past records

_ Costs of purchasing, including related handling and clerical costs

_ Costs of carrying inventory in stock

_ Points at which quantity discounts apply

The annual cost of purchasing and receiving an item is determined by the formula:

Purchasing costs _ or (A) where Cp = total cost to purchase, above unit price, one order quantity, including:

_ Cost to request, process, and issue the required purchase order

_ Cost to receive, identify, inspect, and handle the incoming material

_ Accounting and clerical costs to make payment, prepare records, handle purchase-order copies, etc.

N _ number of pieces used per year Cu _ cost per unit, including freight T _ total usage cost per year to carry N items in stock _ Cu _ N Q _ number of units in a single order

The value of Q which minimizes T is called the "economic order quantity" (EOQ).

The annual purchasing costs can be reduced if fewer orders are placed. This is accomplished by increasing the quantity for each order.

The downside of placing larger orders is that the overall inventory value will increase. Holding or carrying costs for storeroom inventories can be as high as 20 percent of the inventory value per year. The cost to carry a part in a storeroom includes clerk's salaries, space and utility costs, inventory tax, the cost of money, and other specific costs associated with inventory holdings. These costs begin to accumulate the day the part is put on the shelf.

Ch _ holding cost _ (B) where I _ carrying percentage.

Example. Given the following values, determine the ordering costs, the holding costs, and the total expense above the purchase price.

T _ Co _ N _ $5600 per year I _ 20% of the value

Ordering costs __ _ $280 per year Holding costs __ _ $60 per year

Total expense (above purchase price) _ $280 _ $60 _ $340 per year

The total expense of $340 per year to order and hold this part may not be the lowest cost that can be achieved. The graph in Fig. 3 shows the relationship between purchasing costs, carrying costs, and the order quantity for this example.

The lowest total cost indicated on the curve in Fig. 3 corresponds to an order quantity, called the economic order quantity (EOQ). This is the order quantity where ordering costs and holding costs add up to the lowest total cost. The curve also shows that the holding costs and carrying costs are equal at the EOQ. An equation can be derived by setting the equation for ordering costs

[Eq. (A)] equal to the equation for holding costs [Eq. (B)] and solving for the order quantity Q (or EOQ).

EOQ _______ 13 per order (C)

FIGURE 3 Economic order quantity (EOQ).

Exceptions. The clerical effort involved in the usual procedures is not significant compared with the benefits gained in most cases. It should be recognized, however, that some categories of items within the maintenance stores might not justify being controlled either by requisitions or by continuous inventory.

Typically, these are low-cost items used in relatively high volume such as bolts and nuts in common sizes, washers, sandpaper, or nails. This "free stock" may be charged to general expense when received and either issued on request or located where maintenance men have access to it. Periodic checks of supplies on hand will suffice for reordering.

A simple version of the inventory control procedure is called the two-bin system. One sealed bin contains the number of items equivalent to the order point, and the second bin contains the usual excess above this quantity. Stock is withdrawn from the second bin until it is empty, which signals the need for an order to be initiated. With only one bin available for an item, the order point quantity may be sacked or tied together to achieve the same signal for reordering. What may seem at first to be even simpler is the casual inspection of stock items at intervals to initiate required orders. This is suitable as a means of control only in limited storeroom applications, however, and cannot be depended on to minimize either stock quantities or stock-out situations.

Procedural Guidance and Recommendations

Spare-Parts List and the Parts Catalog. In larger operations, where the maintenance worker has access to CMMS data, the maintenance workers are most effective using the spare-parts list or BOM approach to viewing inventory data. The availability of a good spare-parts list can conquer the fears associated with computers and the urge to rummage through the storeroom to find a part. By keying in the equipment they are working on, a complete list of all the available parts is available.

The maintenance worker can readily build an order of all the parts needed for a job. An additional benefit is derived when equipment in the facility is retired or removed from service. The parts associated with that equipment are quickly identified so they can be removed from the storeroom as well.

This reduces inventory as well as freeing up space for other needed items.

In smaller facilities where maintenance worker access to CMMS data is not available, the complex nature of many items tends to require personal selection on the part of craftsmen. Even if a maintenance man could give the generic names of unusual items exactly, only the most experienced storeroom attendants would be able to locate the correct parts consistently. If the maintenance functions are still large enough to justify storeroom attendants, it is desirable to assign definite responsibility to the stores organization for correct inventory records, orderly arrangement of stock, lost or stolen items, etc. This is not easy to do in a clear-cut manner.

An approach that is often worthwhile is to prepare catalog listings of part names, descriptions, and storeroom locations, so that maintenance men can identify and specify code numbers to designate the desired parts. Such catalogs may be prepared directly from the spare-parts list by IT personnel or, where capable, directly from the CMMS software, in which case new or revised copies can be issued without delay when changes occur. This form of catalog development makes it possible to alphabetize all the listings precisely, without requiring any clerical effort to do so. The catalogs may be made more detailed through the addition of illustrations or drawings where necessary, or with drawings, photographs, and sketches from vendors' catalogs. Hard copies of the parts catalogs may be printed and made available to craft offices, material planning personnel, or maintenance men in area locations.

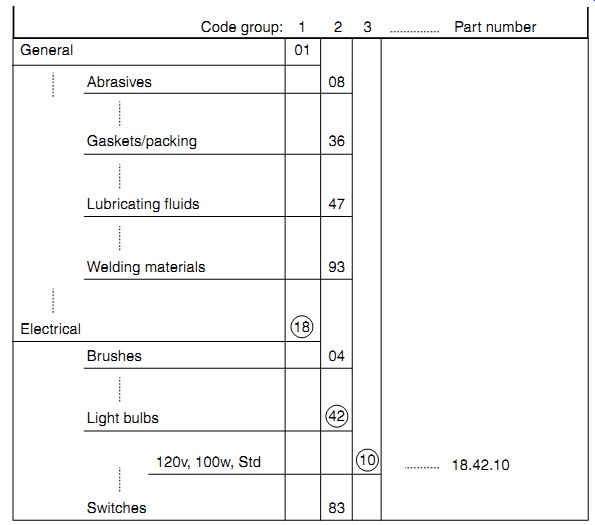

FIGURE 4 Broad category stock codes.

Stock Code Numbers. Stock code numbers (internal plant-assigned part numbers) for each different item in the maintenance storeroom are needed for catalog reference as described above. They are also desirable for precise inventory control purposes, for use in positive identification to purchasing, and as an aid in locating parts within the storeroom. Vendor-specific part numbers generally consist of the vendor's part number (without dashes, dots, slashes, or spaces) preceded by a vendor abbreviation. Adding the vendor abbreviation helps to ensure that no two products will have the same part number. For generic items you will need to develop rules that define what information, in which order, appears in your part numbers. The coding rules must not vary from product line to product line. You must design your rules so that they can be used for all your generic items. A six- or seven digit code, divided into three groups, is often recommended for code numbers, but there is no reason that stock codes cannot be in four, five, or more groups and up to twelve digits. Limitations are only those imposed by the CMMS software that your plant employs. If you are in the process of selecting CMMS, it is desirable to develop your stock code rules and format first and ask your soft ware provider to accommodate your numbering system. Developing an adequate system of numbered categories for maintenance material is important both to simplify the storeroom functions and to use in preparation of a stock catalog. One workable method is to use a series of either six or seven digits, as follows:

_ Digits 1, 2: broadest categories

_ Digits 3, 4: first-level breakdown of broadest category

_ Digits 5, 6 or 5, 6, 7: additional breakdown

_ Continue your numbering until your stock code field is complete.

(Consider using a subfield in the stock code to identify repairable or turn-in items salvaged from a repair action and another to differentiate spare parts from normal stock, consumables, etc.) FIGURE 4 illustrates the method just described. There are provisions for 99 broad category headings. If you have fewer than 99, just number your categories consecutively, leaving unused numbers at intervals so that future additions can be made within the alphabetical spread. This is only one illustration of a stock code assignment scheme. You must determine the right approach for your facility, develop the rules, and then ensure that whatever information management scheme you employ is set up to recognize and interpret your codes.

Material Usage Accounting. It is customary to charge the cost of materials placed in the storeroom to an undistributed inventory account. When finally used, specific items of material are then charged to departmental expense or capital accounts, as dictated by the intended usage. One way to itemize material charges is simply to enter the account charge on the material requisition copy. The required costing of items listed can be done manually or through data-processing methods and can be initiated at the maintenance worker level or maintenance craft foreman level.

There is another way to allocate material charges, which simplifies verification of the charge and permits the accumulation of charges against specific jobs. This method involves (1) work-order copies for all maintenance jobs, preferably in connection with a work planning and scheduling procedure; (2) verified departmental or other charge numbers on each work order; and (3) reference to the work order number on material requisitions. It would then be the function of the accounting department, using CMMS data as input, to match together various items of the following data as needed for cost accounting, work-order performance records, equipment repair records, control reports, etc.:

_ Work-order number

_ Cost-account charge number

_ Equipment record number

_ Hours worked

_ Material cost

_ Abbreviated or coded work description

Additional enhancements can be employed to provide a wealth of roll-up style summaries for the maintenance craft foreman, plant maintenance supervisor, plant manager, and corporate personnel.

Some typical data you may want to consider adding include:

_ Whether work was planned or emergent

_ Production downtime, if any

_ Production capacity reduction, if any

_ Time lapse between ordering and receiving repair part

_ Root failure cause, if identified

This approach is further explained in the case history given later in this section, under the heading, Stores Requisition.

The costing of maintenance material is a function of the accounting department, and procedures should be followed as established by this department. In general, unit costs are developed, as reflected by the latest invoices, and these are entered in the CMMS inventory record or on inventory record cards. These unit costs are applied to the individual requisitions, as a basis for the costing of specific usage quantities. With the budgetary or capital account numbers noted on requisitions, material charges can then be properly developed. This can be a manual process, or it can be handled through electronic-data-processing methods. If performed manually, it is often considered acceptable to round off cents to the nearest dollar when pricing the requisitions.

Coordination with Purchasing Department. Requisitions for replacement stock or spare parts may properly be routed through the purchasing department. The paperwork involved can be greatly simplified through use of a traveling-requisition format. This is typically a CMMS screen, or a printed card or form, that contains the following data:

_ Material description and reference number

_ Approved vendors

_ Approved order quantities

_ Reference dates as needed

When hard-copy cards are used, they are normally kept on file in the storeroom office. If no hard copy is used, the storeroom personnel generally oversee and coordinate the handling of the form and the input and accuracy of the data on the form. When the inventory record (which may be handled by the accounting department) shows that the order point for a specific item has been reached, the traveling requisition card is withdrawn (electronically pulled), dated, and sent to the purchasing department.

After an order has been placed, the traveling requisition card is returned to the storeroom where it is filed separately in a reorder file until receipt of the material. The card is then re-filed to complete the cycle of its usage. In a CMMS system this entire process can be automated by the entry of reorder point triggers, or it can be set up to require manual initiation.

To avoid confusion, one should indicate clearly the repair parts that are to be ordered by the purchasing department from a specific vendor and the normal stock items that can be obtained wherever most advantageous. It is also good practice for the purchasing department to contact the storeroom or maintenance supervisor concerned before ordering quantities that are appreciably different from those specified.

A close working relationship is essential among the storeroom supervisor, maintenance department personnel, and the purchasing department. Each should have well-defined, fixed responsibilities, including cooperating as required to eliminate delays and help control costs.

Special Material Requisitions. When non-stock material is needed for special jobs, requisitions should be channeled through the purchasing department in most cases. For common items obtain able from nearby supply houses and required on a rush basis, a simplified approach can be worked out that retains the needed control. For example, the purchasing department might investigate prices on typical items at one or more supply houses and establish blanket purchase orders with each to cover specific types of material within a given price range. Then the maintenance supervisor or his representative would be authorized to order small lots by telephone or fax, providing a charge reference number from a pre-numbered requisition. The pre-numbered work center requisition would then be routed through the storeroom for internal record purposes.

Obtaining material quickly from both nearby and remote vendors can be simplified still further by making use of global Internet services. You can send your purchase order and account information from a maintenance stores or purchasing department computer terminal via the Internet directly to a selected vendor's retrieval, packing, and shipping center, even designating the shipping mode desired. Restrictions are needed, of course, to prevent lack of control with such installations. The discussion under Systems Contracting below describes a more comprehensive approach along this line.

Salvaged Parts and Material. It is good practice to route salvaged parts from a repair and/or maintenance job back into the maintenance storeroom for subsequent issue in the same manner as new material. This can also be provided for repairable salvage (either in-house or vendor repairable) by identifying repairability in the stock code. Identifying repairable items this way can automatically alert the user to turn in the salvaged item when he is ordering the replacement. Applicable accounting practices are covered in another section of this handbook.

Standardization. Continuing efforts should be made to obtain the maximum degree of equipment or parts standardization within the plant. The maintenance supervisor should be expected to coordinate and promote such efforts. This is not an easy job, but tangible results can be achieved with some effort. A key step is to review requests for new plant equipment at a stage which will provide the needed maintenance background when making decisions among competitive items of equipment.

Standard equipment parts such as controls, motors, hydraulic units, and pumps may properly be specified on certain equipment. When obtaining new equipment, the specifications should be examined to determine existing applications with the same, or essentially the same, specifications. It may be possible to upgrade the existing applications at the same time the new equipment is being installed, and the economies of quantity purchasing may be substantial enough that when considered together with the advantages of standardization, upgrade may make the most sense.

Another approach, as repair needs become evident, is to make replacements with standard parts wherever practical, even though some minor equipment revisions are required in doing so. An aid in working toward standardization of parts is to enlist the cooperation of manufacturing engineers who investigate new equipment possibilities or plant engineers who design new facilities. If a parts catalog is made available to such men, the selection of standard parts and materials for new equipment can be made where practical. A good CMMS can also search application specifications for matches to identify where different equipment is providing for the same or similar application.

Control Indexes. Records of the total inventory cost and average turnover interval are important and should be developed regularly. The average turnover can be calculated by dividing the cost of stock disbursed during the year into the total inventory cost. Of course, depending on the size of your operation, you may add a financial analysis module to your CMMS suite which can provide reports formatted for specific data users.

When we determine such figures, it is important that we classify spare parts separately from nor mal stock. The average turnover interval for the latter is 2 to 6 months, while the average spare-parts turnover may properly be much longer than this. The necessary separation in reporting will be facilitated if distinguishing symbols are used in the stock codes for each of the two classes.

Investigating in detail the most active items involved can facilitate the control of inventory cost and turnover. In most cases, a small percentage of categories stocked (say 10 percent) will account for a large percent of inventory investment.

Other reports should be developed to provide information such as the following:

_ Variances between perpetual inventory records and periodic physical inventories

_ The number of, and identification of, stock-outs that occur

_ Stock losses through obsolescence, deterioration, or shelf life expiration

Equipment Repair Records. Reference was made previously to methods of pricing material requisitions and including these data as part of comprehensive equipment-repair records. Such records may be as simple as completed work-order copies filed by equipment number. A step beyond this would involve hand or computer posting to equipment record cards of data such as summarized work-order descriptions plus labor and material costs. Going still further, CMMS analysis modules can provide periodic summaries of maintenance labor and material costs for each item of plant equipment, with work details available from the work-order files to analyze the reasons for excessive costs.

This information should be reviewed regularly to determine what steps can be taken to reduce repair needs. It may be found that regularly scheduled corrective maintenance work is needed on some equipment to prevent recurring breakdowns. In other cases, preventive maintenance inspection or servicing should be initiated that could detect imminent failure. Systematic approaches of this kind are an integral part of the maintenance control program and are an additional reason to consider a fully integrated CMMS software solution.

Systems Contracting

Previous sections of this section have described systems for internal stores control of maintenance material. The aim is to assist in minimizing total maintenance costs. There are definite costs in the control procedures themselves, however, which can be summarized as follows:

_ Cost of interest on the inventory investment

_ Cost of storeroom attendants

_ Cost of storeroom space and related equipment

_ Overhead costs related to purchase-order handling and stores record keeping

_ Cost of depreciation, obsolescence, and theft of stored material

_ Cost of taxes and insurance, where applicable

While evaluation of these costs in a specific plant would require a careful study, their yearly total is seldom less than about 25 percent of the average inventory value. Even in cases where purchased maintenance material is initially charged to operating expense, the above costs are still incurred so long as the material is stored in some manner prior to usage. Such costs can be offset only by two sources of savings:

_ Possible economies in purchasing when buying more than day-to-day needs

_ Reductions in production downtime or maintenance waiting time because needed material is on hand when required

Vendor Contracting. For plants within or near larger metropolitan areas, it may be possible to gain the latter source of savings while greatly reducing inventory costs. The key lies in arranging for prompt delivery or pickup of material from vendors, along with their assurance of dependable ser vice at reasonable cost. Typically, 80 percent of the dollar value within maintenance stores is attributable to 20 percent of the item categories that are stored (the 80/20 rule). Thus fast delivery service on even a limited number of high-cost items could make a big dent in total material costs. In the past, however, purchasing restrictions and other reasons have usually curtailed this approach. Overnight or next-day delivery services abound today, and some may even have second- or third-day delivery guarantees. The cost of these services is not cheap, especially for large, bulky, or heavy items. The costs of holding in inventory must be weighed against shipping costs to determine the economics of these delivery services.

In recent years, many companies have found it practical to shift toward greater dependence on nearby vendors for maintenance material, through a form of advance contracting that provides the needed safeguards. Terms such as stockless purchasing, contract purchasing, or systems contracting have been given to such arrangements. In general, these plans can often reduce total procurement costs if they are carefully implemented.

Implementation. First, analysis is required to establish the classes of material, which can be obtained from nearby vendors, assuming delivery schedules are worked out. Ideally, if more than one source is available, the best approach is to send a request for proposal (RFP) to each vendor that lists the materials, grades, quantities, and number of orders per year and delivery requirements.

This competitive bid approach will allow you to choose the least expensive alternative, but do so only after you have checked the vendor's service records with other companies. The lowest bid is not always the cheapest if the vendor cannot deliver. When the basic conditions of delivery plus vendor supply capability appear to be satisfactory, the purchasing department, to establish price levels and certain commitments, calls for negotiations. The commitments must not be one-sided for a satisfactory arrangement to be established. Consistently good service for specified items should be expected from the vendor, with unit prices agreed upon in advance. Continuation of the agreement should be contingent on satisfactory service by the vendors involved. In return for such promised service and price quotations, the purchasing company should indicate what the previous order quantities have been, and should follow through with the placement of orders approximately as forecast.

Vendor Catalogs. An internal stores catalog was recommended in preceding sections of this chap ter. Similarly, a list of items, which each vendor agrees to stock, is desirable, with negotiated prices being indicated in each case. The listed prices should be based on normal delivery requirements, with recognition being given to possible added costs for emergency calls that may require overtime or special handling. The catalog should list the vendor's order numbers, for simplified ordering by those authorized to do so.

Ordering Procedure. With contractual relationships developed, catalog listings provided, and delivery schedules agreed to, the process of placing an order can be done in various ways. Routine mailing of the order is one way; and, as previously mentioned, there are now several quicker methods. In any case, provision should be made for strict adherence to established procedures on the part of ordering personnel. This will include reference to charge numbers, delivery points, delivery times required, and other data that are normally part of the purchase order procedure.

Relation to Planned Maintenance. Implementing and optimizing maintenance stores and material inventory control is just one of the ways in which total maintenance costs can be reduced. Daily planning and scheduling of the majority of plant maintenance work can be implemented so as to control maintenance labor costs, inventory purchasing, and holding costs and also to control production losses from breakdowns. An orderly, pre-negotiated systems contracting arrangement for maintenance material can be much more effective in such cases than in "hand-to-mouth" situations where the maintenance department is simply responding to emergencies.

PREV | NEXT | Article Index | HOME