If you had just landed on these shores a few hundred years ago, water and wind would have been the energy sources you could most readily see and use (apart from wood and —in a passive fashion—the sun). You’d have needed only a few tools and a modest technology, and you would already have been familiar with their ancient, world wide applications.

Of all the known energy alternatives we have not yet discussed, water and wind are the two that individuals, as well as large concerns, can use to generate electricity. However, although such a feat is possible, it is generally unrewarding, and it requires special precautions.

• Water: Water is clean, renewable, and an extremely efficient source of power. Properly harnessed, 80 to 90 percent of the available energy in a moving stream can be used, compared with the 25 to 50 percent energy efficiencies of other major power sources.

Simple water wheels have been used to grind grain for at least three thousand years. More recently, massive multi purpose installations have provided irrigation and flood control; lakes and waterways in the form of dammed-up reservoirs; and about 12 percent of America’s electric power. Encouraged to seek out other options by the rising costs of fossil fuels, a growing number of individuals, on their own and with the support of government and industry, now consider water to be a component of their long-term energy programs.

If you live in the heart of a major metropolis, you will have to wait for water power to come to you. But if you live on or near even a small vigorous stream; if you like the idea of energy-independence; if you enjoy working with your hands; and if you have a few thousand dollars to invest in your dreams, you can provide yourself with an independent hydroelectric plant that will run anything from a few light-bulbs and your kitchen clock to your most complex electric appliances.

Unless you’re an experienced handy- person, building and installing your own waterwheel is going to be very hard and possibly dangerous work; and when you’ve finished, the chances are excel lent that you will find it would have been cheaper to tie into the existing energy grid than to make your own. Nevertheless, some people have constructed wheels that generate enough electricity to provide an excess, which the proud wheel-owners then sell to the local utility, thereby amortizing their expenses on the project more quickly than they could have otherwise.

All hydroelectric plants need moving water. Whether you are already on a piece of land with a stream, or a river, or whether you are looking for water course acreage to buy, consult with a lawyer or your local Department of Agriculture office early in the planning stages to familiarize yourself with all laws and regulations governing water power.

Assuming that you have found the right watercourse, and that you can build a wheel where it flows, make sure that the water moves 12 months a year—if it dries up in summer or freezes sol id in winter, you are up the creek with out any power. However, if the water does run all year, even if the stream is small, you will probably have enough of what you need to achieve minimal electrical generation.

Water power is measured by its flow (the volume and speed of the stream) and its head (the distance the water falls from above to the exit of your power plant). Potential energy, stored in the water supply, becomes kinetic energy as the water runs down the sluice that channels it to your wheel; and it be comes work when the water strikes and drives that wheel.

Your wheel’s efficiency is determined by how much of the water’s movement is consumed in turning your wheel. The ideal power plant directs a fast mass of water against the blades of the wheel with exactly enough impact to transfer all of the water’s kinetic energy to the wheel and turn it. Efficiency of 100 percent is achieved when the water then simply stops.

In order to provide enough water with enough head that moves often enough to make a waterwheel workable, you need some form of water reservoir and some form of precipice (frequently these are combined by use of a dam). The best situation is for the water sup ply to be backed up into a natural holding-tank such as a swamp. Ideally, the water drains from the swamp at its narrowest point, raising the velocity of flow just before the water drops over a water fall, to provide you with maximum head at minimum expense. Otherwise, you may be faced with some serious work- dredging your reservoir and building your dam—before you are ready to go to work on your waterwheel.

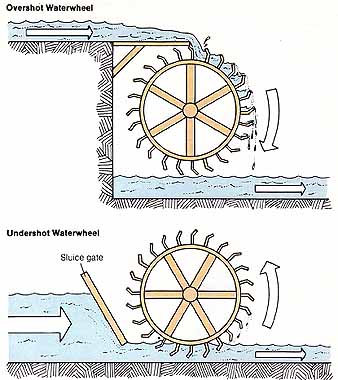

Overshot Waterwheel; Undershot Waterwheel

The simplest type of waterwheel is the overshot wheel, which requires neither fancy equipment nor delicate balancing acts to build. Water is carried through a sluice above the wheel; a gate regulates the amount of water entering each bucket, or striking each blade, on the wheel just as it reaches its peak; and the buckets hold their water as far down the wheel as possible be fore turning and spilling it, in order to produce the largest possible energy transfer and power gains.

A slightly more complicated version is the undershot wheel, in which only the lowest buckets or blades are struck by the moving water. The impact of the water, combined with the weight of the water itself, moves the wheel.

In our sophisticated times, these simple waterwheels have proven inefficient for the large-scale generation of hydroelectric power. Turbines, originally developed during the Industrial Revolution, can be highly efficient, but they require precise engineering. In a turbine, the sluice directs the flow of water to strike the turning wheel’s blades at a specific, very exact angle to produce high turning-speeds and , consequently, large quantities of electric power.

Obviously, if you plan to dip into water power at all, you will need either some training or a good deal of trained assistance. For information ranging from legal issues to technology to the names of contractors, call your local US Department of Agriculture Resources Conservation District. But stay on top of your project—otherwise you may find yourself with a wheel that doesn’t turn, suspended beneath a dam that doesn’t hold, over a stream that no longer flows, going nowhere and producing nothing on a project that will cost you several thousand dollars at the very least.

• Wind: Like water, wind is clean, renew able, and potentially efficient. Like water- wheels, windmills have been used to grind grain and to pump water for thou sands of years. and like water power, wind power has received a burst of technological attention in recent years.

Just as you can harness water power, so can you harness wind power. But again as with water power, the expense of constructing the apparatus for a small-scale operation is unlikely to be recouped in any great hurry. In fact, un less your present electric bill exceeds $200 per month, the wind speeds around your house average more than 10 miles per hour, and you have a bare minimum of $10,500 to blow away, your personal pursuit of wind power should be accompanied by a deep religious commitment.

Windmills have a prodigious number of application problems. First, wind energy is highly site-specific. Just be cause the wind is blowing here and now does not mean that it will blow there and then, even though “now,” “here,” “there,” and “then” may be only a few feet or minutes apart.

Second, any wind-catcher must be located well above its surroundings, such as buildings, hills, and trees.

Third, wind is a very intermittent energy source. The wind—especially a strong one—does not blow regularly, in most places.

Wind power is most useful if the work it performs can be stored. Typically, wind power is collected for electrical use with a DC generator, and transformed to AC for storage in batteries. But it can also be tied into a public utility grid to be fed into the larger system when an excess is available. Most electric utilities in this country charge about 8 to 10 cents per kilowatt hour. Since your generating cost is likely to be as much as 20 times this amount, you will not come out the winner in this exchange. However, you may be able to cut your losses.

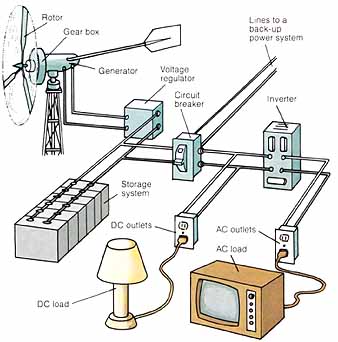

Any electricity-generating windmill is an integrated system, composed of propellers, a generator, a voltage regulator, inverter and some sort of storage. If you are keen on becoming intimate with your system and plan to do only a nominal amount of work with your self- generated electricity, you may be able to put together a system from components on your own. But if you plan to do a great deal of work with your electricity —if, for instance, you plan to operate not just your light bulbs and TV but also your washer, dryer, and refrigerator—then there’s no point in buying anything less than a complete wind- generator system.

In a wind generator, the propellers are turned directly by the wind. Because they ordinarily turn too slowly to ensure the high rotational speeds necessary to run the generator, they usually are connected to it through step-up gears. The generator turns the wind energy in to electricity, which is monitored by the voltage regulator to provide constant electricity to the batteries, which store the electricity for use on windless days.

If you’ve decided to convert to wind power, you must be knowledgeable about a variety of factors about your own energy consumption as well as about the hardware available.

1. Know your annual and seasonal consumption, and know which uses of electricity you are willing to do without, if necessary.

2. Know the annual and seasonal windspeed averages where you plan to erect your windmill.

3. Know that your wind access can not be blocked by a new high-rise or a growing stand of trees.

4. Go out to see existing windmills; talk to their owners, the people who in stalled them, the people who sold them, and the people who manufactured them, if possible. Find out what, among the available hardware, truly suits your needs.

5. Assume that you will need more electricity than you think you will, and that your windmill will produce less than you think it will. These pessimistic fore casts will make you happier in the long run.

6. Provide yourself with a backup power source for emergency situations.

7. Remember that you are dealing with far more power than is necessary to kill a person, and be careful. (This is true whether you are building the wind mill yourself or having it built and /or installed for you.)

Wind Electric-power-generating System