How to find and straighten the grain of woven and knit yardage.

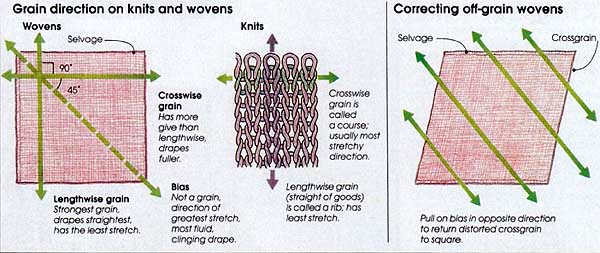

If the fabric you’re planning to sew with was woven or knit, it has grainlines. And if you want your project to turn out as well as possible, the first thing you need to do with that fabric is make sure the grains are straight. Checking the grain of new fabric as soon as you get it home gives you the choice of returning it at once if it’s flawed, or correcting it before you sew with it. Here’s how to tell your fabric is off grain, and what to do about it if you still want to use it. The drawing on the facing page shows how to locate the various grainlines, and describes how they differ. Let’s consider woven fabrics first; I’ll come back to knits later.

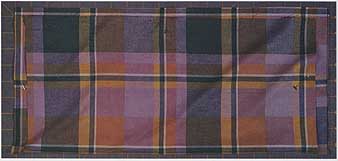

Every sewing project should start out with a layout like this:

The woven yardage has been pinned in half, with selvages and cross grain

ends together. If you see wrinkles at the fold, like those you can see here,

your fabric is off grain. Read on for your options.

Why grain is important

The significance of grain is as simple and fundamental as gravity. If you want your garment to hang smoothly, with out wrinkles and distortion, it must be cut so that one of the grainlines hangs vertically, plumb with the center front, the center back, and with the center of the sleeves. In most garments, this vertical grainline is the fabric’s lengthwise grain. Garments are sometimes cut with the crosswise grain plumb with the centers to take advantage of a crosswise pattern or do sign on the fabric. Of course, some garments are cut with the centers on bias, but hat’s another topic.

In woven fabrics, either grain can work as long as you position it precisely when cut ting to parallel the garment centers (and thus the pull of gravity), and as long as the lengthwise and crosswise grains are at exactly right angles to one another to begin with. Cutting exactly on a grainline depends on accuracy when laying out your pattern pieces. To make sure the grainlines are square to each other you may have to manipulate the fabric before cut ting. This is what “straightening the grain” means. Both steps are critical for grain- straight garments.

How fabric gets off grain

When fabric comes from the loom, the crosswise, or weft, threads are at exactly 90 degrees to the lengthwise, or warp, threads. In other words, it’s grain perfect. But before it gets to the fabric store, all commercial yardage has been rolled back and forth from bolt to bolt for processes such as -finishing, printing, and cutting. Each time it’s rolled, it stands a chance of being pulled off grain.

If the fabric has a permanent finish applied to it after being pulled off grain, the grains will be permanently locked in the off-grain position, and can't be straightened. Permanent finish designations include “permanent press,” “durable press,” “crease resistant,” “stain resistant,” “water repellent,” and “bond ed.” A permanent finish will usually be noted on the end of the bolt. Temporary finishes, which may be labeled “pre shrunk,” “shrink resistant,” “Sanforized,” or “flame retardant,” will wash off and won’t affect the grain.

How to check the grain

The best way to check the grain of a woven fabric is to lay the edges together, selvage to selvage and crossgrain to crossgrain, and see if the fabric lies flat. To make sure you’ve got the crossgrain, you can pull a thread on one end of the yardage and cut along it or tear the fabric from selvage to selvage. If the fabric has a crosswise woven-in stripe, you can cut along the edge of that stripe. Printed stripes can’t be used to verify grain, since the design could easily have been printed when the fabric was off grain. For this initial checking, it’s only necessary to establish the cross- grain on one end.

Pin the crossgrain line to itself on the straightened end. Place the yardage on a flat, smooth surface, and pin the selvage edges together. Ideally, your working surface will have a grid pattern on it so you can use it to check straight edges.

If the yardage lies smoothly on the board with no ripples along the folded edge, the grainlines are straight, and you can now preshrink it. Most fabric will be in this category. But if the fabric has ripples along the fold line, like those in the photo on the facing page, the crossgrain isn't at right angles to the length wise grain, and you should straighten it, if possible, be fore proceeding.

I straighten every length of woven yardage I buy, unless it’s so loosely woven or light weight that the grain shifts just from handling it, as with some chiffons. With these fabrics, you should establish the crossgrain at each end as usual, but you can often correct the grain as you lay the fabric out for cutting, holding it in place with weights, especially if your cutting surface has a straight reference. Sometimes you’ll discover that the crossgrain is curved. It’s usually possible to correct this kind of distortion by adjusting the fabric as it lies flat, and steaming it.

Straightening the grain

If your fabric needs straightening, first unpin and unfold it, then trim the other end along the crossgrain, so you can check both ends after straightening. To return the crossgrain to its original position, simply pull on the bias in the opposite direction of the distortion, as shown in the right drawing above. Start in one corner, grab the selvage in one hand and the raw edge in the other, and stretch them apart on the bias, then move your grip on both edges down a few inches and stretch again. Repeat across the entire length of the fabric.

Obviously, this stretching can be a challenge with wide or heavy fabric, and you may need a helper, or a bit of ingenuity. I’ll sometimes step on one edge to hold it as I pull with both hands on the other. After pulling across the whole thing, realign the edges to check your progress; you may need to do it again or even to stretch a bit in the opposite direction, if you’ve overdone it. If the fabric seems difficult to straighten, try steaming or dampening it first.

Once the fabric is straight, with no ripples along the fold line and both grainlines parallel with the lines on the board, re-pin the edges and steam the entire piece. Let the fabric re lax flat for at least eight hours. Occasionally a permanent finish will not be reported on the bolt end. If that’s the case with your fabric, it will return to its crooked state as it relaxes, and it will be impossible to straighten.

Grain direction on knits and wovens: Wovens; Crosswise

grain: Has more give than lengthwise, drapes fuller; Lengthwise grain: Strongest

grain, drapes straightest, has the least stretch; Bias: Not a grain, direction

of greatest stretch, most fluid, clinging drape; Knits: Crosswise grain is

called a course; usually most stretchy direction; Lengthwise grain (straight

of goods) is called a rib; has least stretch. Correcting off-grain

wovens: Pull on bias in opposite direction to return distorted cross

grain to square.

Last resorts

So what can you do if you can’t straighten the fabric? Return the fabric to the store, or use it knowing the cross- grain lines are not straight. If you cut the garment so the centers are parallel to the lengthwise grain, ignoring the crossgrains, the garment will hang straight, but any visible crossgrain design line will be distorted and will be impossible to match at seams. If the fabric is plain or patterned only lengthwise, you may never notice the imperfection. To cut the off-grain fabric, release the crossgrain ends and pin just the selvages together so there are no ripples along the fold line. After the fabric is preshrunk, cut it as pinned. If you had planned to use the fabric on the bias, return it, because the bias direction only works with grain- straight yardage.

Preshrinking

I never cut a woven or knit garment without preshrinking the fabric. Even if the fabric doesn’t shrink, it will of ten handle more easily after preshrinking, and if it doesn’t launder or clean well, I want to know that before I put a lot of time into it. Hand or machine baste the ends and selvages together to preserve the grain during preshrinking.

However you plan to clean the garment, put the uncut fabric through the same complete process, to avoid an unpleasant surprise the first time you clean the garment. In other words, wash washables with soap, and dry-clean dry-cleanables, don’t just have them steamed. Wetting from the cleaning fluids can cause additional shrinkage.

I’ve used the tailors’ method of shrinking woolens, called London shrinking, which means wrapping the yardage in a damp sheet until it’s moist, letting it dry, then pressing it, but I think it’s too time-consuming. I prefer to let the cleaner do it.

Working with knits

The main difference between knits and wovens in terms of grain is that, while cutting on the straight grain is equally important to the drape of the knit or woven garment, the grain in a knit can't be corrected if it’s off. In fact, knit fabric really doesn’t have a grain as we know it in wovens. All you can do is locate the straight of goods and make sure you’re cutting on it. The straight of goods of a knit is the wale or rib running in the lengthwise direction. The crosswise element of knit fabric is called the course. Rolling the fabric from bolt to bolt can also distort knits, and if finishing is applied when the fabric is distorted, the distortion could be permanent, so check the relation ship of the ribs and courses in the store, especially if there’s a crosswise stripe or printed design. But, as with wovens, even badly off-grain knit yard age will hang straight if cut on the straight of goods.

Unlike wovens, which I straighten and baste before preshrinking (so the cleaning doesn’t add to the distortion), I establish the grain in knits only after I’ve preshrunk them, which will relax any distortion that’s not permanent. I baste the edges together before preshrinking so that the agitation doesn’t distort them further. It is important to wash cotton knits twice to preshrink. After cleaning or washing, release the bastings, then locate a ribline by pinching the fabric, folding it until a rib is parallel to the fold. Move your fingers along the ribline, pinning at right angles every 4 to 6 in. Work from the center to each end.

If the layout calls for a single fold and a double layer throughout, pin the ribline at the fold, usually along the center. If you need a single layer of fabric, replace the pins with a thread-tracing through a single layer of the knit along the pinned ribline. If the layout calls for several different folds, pin a ribline the length needed for each fold as you cut out the pieces.

Gently shake the knit fabric and flip it onto the cutting surface as you would a sheet on a bed to smooth the fabric, then align the pinned ribline with a straight line on the board. If the edges of the fabric want to roll, spray-starch them.

When you’ve prepared your woven and knit fabric properly ahead of time, your garments won’t hang crooked on your body, or shrink when cleaned. And best of all, when you have a burning desire to sew, you can begin your new project at once.

Choosing a grain board

Whatever tabletop surface you choose for your sewing workspace, make sure it has an overall grid so you’ve got a clear, reliable, and ever-ready reference for straight lines. You’ll find this useful in many ways, but especially during the grain- straightening process, as described in this article. Even those folding cardboard cutting boards can be useful. They’re pinnable and easily stored. But if you can leave your area sot up permanently, I’d recommend either buying a table-sized, gridded rotary cutting mat, or, if you prefer a padded surface, making one with a checked fabric top.

If you choose the mat, provide yourself with a lot of inexpensive, small weights, so you can use them liberally, since you can’t pin into the mat. I have a large collection of heavy metal nuts (as in “nuts and bolts”), each about an inch wide, which I typically space about 4 to 6 in. apart around paper patterns and the edges of unruly fabric. Even if you don’t use the cutters, these mats make good working surfaces. There are several sources for inexpensive gridded mats that will cover up to a 4- by 8-ft. table, and can be easily trimmed to smaller sizes.

If you’d like a padded, pressable surface, cover a sheet of ¾-in, exterior plywood (I used a full 4- by 8-ft. sheet supported on a pair of saw horses) with a couple of layers of wool blanket, or with nylon spring-back flannel, the padding used by dry cleaners on their presses, available from tailors’ and cleaners’ suppliers. You can also contact Covers, Etc. For the top, I used a woven-check cotton tablecloth, since it's more substantial than gingham. Staple it carefully to the underside of the board, making sure the stripes are straight and square to one another as you stretch the fabric over the padding.