Is this an effective method for waterproofing?

I asked a lumberyard proprietor the other day if he would build a wooden foundation for a home he was going to own. Wooden foundations are very much in the talk stage now, and many are actually being built. Since this man was in the lumber business, I figured he’d have nicer things to say on the subject than the concrete man down the street. He did. But not much.

“That depends,” he replied. “If I were building a split-level into a well-drained hillside—where one wall is exposed on the bottom floor—I would think a wood foundation appropriate. The key is good drainage. If you have it, a wood foundation is feasible. And if you decide on one, the codes are quite strict on good drainage. Then if you use a good pressure-treated lumber like the Wolmanized brand we carry, you should be okay. As any farmer can tell you, a wood post, even untreated, rots hardly at all down in the ground. It’s the part of the post at the soil surface where oxygen is plentiful that rots fast. And treated wood takes care of that.”

Maybe so. But none of the reputable builders in this area will recommend wood foundations, partly because the excellent drainage necessary is hard to achieve in our heavy clay soil and humid climate. I picked up a copy of the 30-day limited warranty on Wolmanized residential lumber, which the lumber dealer had recommended for foundations. After the warranty statement, there is the following disclaimer: “Warrantor shall not be liable hereunder for damage to Wolmanized residential lumber used in foundation systems, in water immersion applications....Warrantor shall not be liable for ... the natural characteristic of some wood to check, warp, or twist, or for any incidental or consequential damages.”

Wood Foundations

Good pressure-treated lumber is great stuff, don’t get me wrong. It will resist decay and termites and it can be used in contact with the ground. I have used Wolmanized lumber that way on a pole barn and it shows no decay in eight years. We used the lumber to build the deck on our house ten years ago, and it has survived well in all kinds of weather. The greenish cast from the copper in the preservative can be painted over with a dark stain to give it a more natural wood finish look.) But in foundations, treated wood has not yet stood the test of time.

One of the chief reasons for hesitancy over wood foundation walls has to do with lateral strength, not decay, and is the main reason the searcher for low maintenance ought to be dubious about not only wood, but concrete block as well. A friend of mine tells a sad tale about the house he built. On the back and side walls of his split level, he used 12-inch concrete blocks for extra strength, rather than the usual 8-inch ones. The house was already well along in construction when a heavy cloudburst filled the ground cavity around the walls with water. The builder had neglected as yet to provide for fast drainage away from the wall. Hydro static pressure in the column of water against the wall was so great (and always is) that to my friend’s unbelieving eyes, it bowed those 12-inch concrete blocks 4 inches at the center of the back wall, racking the half- finished house so all the door frames were out of square. What would hydrostatic pressure have done to 8-inch walls in that situation, or a flimsy wood-paneled foundation wall?

The Importance of Good Drainage

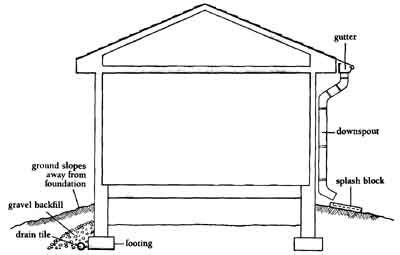

Experienced builders install the tile drain down along the base of the footer as soon as they put in the footer. “And get that tile down at the base of the footer all the way around,” emphasizes Kenny McClain who built our house. “If it’s even half a foot up the side of the wall, water can lie under it and cause problems.” As soon as the roof is up, make sure there is spouting to carry roof water away from the house in case of heavy rain before backfilling and grading are completed. Even after fill dirt is in place against the wall, a problem can present itself. After three years or so, the backfilled dirt will settle lower than the lawn out from the foundation. When this happens, in a downpour the rain that runs down the house walls lies against the foundation rather than running away from the house, and it may cause trouble.

Hydrostatic pressure coupled with the tendency of some heavy clays to expand when wet can be quite strong even after backfilling, if the weather is unusually wet and the freshly backfilled dirt is saturated with water. The November of 1985 was the wettest on record in our locality. “There was so much water in the ground that drain tile couldn’t carry it away fast enough, and I’m awfully glad I didn’t have any block foundation walls in progress,” says McClain. “I’m sure they would have fallen in. It does happen.”

A good drainage system is the key to a dry basement.

Block versus Poured Concrete

When you are building or renovating, you can always find block layers who will quote a price for a block foundation a little cheaper than a poured concrete one. But it will take them longer to finish during that crucial time when your excavation is exposed to the weather. If they do the job right, that's , fill about every fourth row of blocks with concrete and bond the wall tight with reinforcing rod through the blocks, the cost will come close to the cost of poured concrete. Moreover, block walls require more waterproofing than poured concrete. The blocks need to be plastered on the outside up to grade line and then coated with tar, at least. Better than tar, which eventually dries out and forms tiny cracks, are various concrete sealers on the market. Thoro System Products ( 7800 Northwest 38th Street, Miami, FL 33166) is a well-known manufacturer of such products. Another sealer that's much better than tar for damp- proofing is Owens Coming’s Tuff-N-Dri ( Fiberglass Tower, Toledo, Oh 43659). It is a polymeric coating that's sprayed onto the outside foundation walls. The coating is somewhat elastic and does not crack if there is shrinkage in the wall, as tar does. And it remains elastic at below freezing temperatures, too.

Although you also ought to coat the outside of poured cement walls with tar at least, such walls are not as porous as concrete block and don't require plastering. Another advantage of poured concrete is that once the forms are pulled, the dirt can be filled in over the footer tile (which should have about a foot of gravel directly over it first for good drainage) immediately, and the ground around the house can be graded right away.

Waterproofing the Foundation

A new way to drain away water and keep foundation walls drier is with waterproofing panels or mats, which are installed on the outside of the walls after they have been conventionally waterproofed. The interior of the panels or mats is expanded polystyrene or high-density fiberglass that quickly drains or wicks water entering through the exterior filter fabric, down to the tile drain. Thus, hydrostatic pressure is relieved. The panels are also insulative and protect the waterproofing on the foundation wall from harm during backfilling. (But the panels are not meant to take the place of regular waterproofing.) If drainage problems are severe, manufacturers suggest using both the panels and gravel. Cost ranges from $2 to $4 per square foot but manufacturers claim that the products are cheaper than hauling and installing gravel over the tile. These panels seem like they’re a good investment, but only time will tell. Manufacturers include:

American Wick Drain Corporation (301 Warehouse Drive, Matthews, NC 28105); Eljen Corporation (15 Westwood Road, Storrs, CT 06268); Geotech Systems Corporation (100 Powers Court, Sterling, VA 22170); JDR Enterprises (725 Branch Drive, Alpharetta, GA 30201); Mirafi Inc (P0. Box 240967, Charlotte, NC 28224); and Owens Coming ( Fiberglass Tower, Toledo, OH 43659).

Where drainage away from the house is less than perfect, and water proofing the outside foundation is not enough to stop leakage through the wall, waterproofing the inside wall can help. Thoro System Products, mentioned above, sells some of the most advanced products for the job.

Insulating the Foundation

A low-maintenance foundation wall needs to be insulated well on the outside. Rigid 1-inch foam panels are placed over the entire 8-foot wall, and good builders like to put a second 4-foot layer around the top half of the foundation wall. The blue panels with a higher R-value than the white are almost always worth the extra cost for a house.

Pouring Concrete Foundations

In pouring the concrete walls, you can save some of the cost by using the wood in the forms for house construction later on. But the trend now is toward aluminum forms (which originated in Japan) because they are light, easy to use, and virtually indestructible, lowering the cost of poured concrete walls considerably. These forms also allow for easy installation of reinforcing rod and wire.

Another clever aspect of the metal forms is that some are designed to leave an imprint of bricks on the inside wall, complete with recessed mortar joints. After the forms are removed, one can go over the wall with a paint roller—any color you desire—and paint the “bricks” without touching the “mortar lines.” The effect is barely discernible from the real thing unless you look closely, and it results in an attractive wall of 100 percent low maintenance and durability.

This is a perfect example of how low maintenance can also mean low cost. Leave it to the Japanese. You will hear it often in this guide: We ignore the primal beauty of masonry, metal, and sometimes wood in favor of decoration with fake masonry, metal, and wood. Even concrete blocks need not be ugly, as I try to make apparent in the next section. Nor is it al ways prettier to cover concrete walls and floors with some kind of paneling or tile. For example, at Ohio State Univ. in Columbus, the walls of underground halls and rooms are the poured concrete itself, unadorned or sometimes tinted, the form seams boldly evident. The effect is most attractive. This idea could fit tastefully in home decor, too. Low maintenance and low cost.

Making Concrete Better

Improvements in concrete are being made all the time. There are chemicals that can be added to make it set up faster or slower than normal. The latest trick is an additive that makes the concrete workable without water or with only a very small amount of water. When you consider that conventionally you need about 5 gallons of water for every sack of cement, you can understand the savings in transportation costs alone.

Incidentally, you won’t save much money trying to mix concrete yourself, except on very small jobs. I paid $60 a cubic yard for ready-mix (2008). I found that if I had had the gravel and sand hauled in, bought the bags of concrete myself, and rented a mixer, I would have had to actually pay that $60 for the privilege of doing all that work of mixing myself. And I wouldn’t have gotten the consistent quality of ready-mix either. Rarely I hear stories of ready-mixers who cheat on the proper amount of cement, or (more often) whose sand is dirty and therefore won’t bind into a solid concrete, but I doubt this happens very often. The cheater would be too soon out of business.

Tinting

Integral color in concrete (pigment added directly to the concrete during mixing) gives much better results if white portland cement is used, unless you want dark colors. White portland cement and white sand make a pure white masonry mortar that can be used with almost exotic effect. I once laid a slate floor in an entryway with white mortar, and it was a real showstopper. White portland cement and pigments to color concrete add considerably to the cost, but no more expense or maintenance will be necessary on that wall.

The Proper Concrete Mix

The standard concrete mix is 5 bags of cement (94 pounds each or 1 cubic foot) per cubic yard of concrete, which works out to approximately one part cement to five parts aggregate, the aggregate usually being two parts sand and three to four parts gravel.

How do you tell if the concrete is wet enough? The traditional test is to dump a cupful upside down on a level surface. If the concrete holds its shape fairly well, it has the right consistency. If it slumps out flattish, it's too wet. If it doesn’t slump at all, it's too dry. I like it a trifle on the wet side because it works easier. But if concrete is too wet, it will make a weak wall.

Signs a Foundation Might Need Repair:

Cracks in Brick Facing

Chimney Cracking or Leaning

Drywall Cracks

Sinking Foundation

Uneven or Sticking Doors or Windows

Large gaps in window and door frames

Interior plaster walls cracked

Walls are beginning to lean noticeably

Window and/or door trim are developing spaces

Floors are starting to settle and become uneven

Foundations are sinking

Cracks found on foundations, basements, slabs, and/or concretes walls.

Stair step and horizontal cracks in the mortar joints.

You may not need a new foundation. Look for a bonded and insured contractor who can repair the foundation cracks often with a strap, epoxy injection or a pad known as an underpin, making yours a safer home.