In the early days, many log cabins were considered as only temporary shelters, something to get by in until a “real” house could be built. Consequently a lot of shortcuts were taken, especially with the underpinnings. The pioneer in a hurry just dug a shallow furrow in the ground, dropped the first course of logs in, and packed the earth around them. The floor of the cabin was often packed earth as well. Many of the pioneers took the process a step further by placing a few stones on a level patch of ground and resting the first course of logs upon them. This worked a little better, but the stones eventually sank down and left the first course on the ground anyway.

The next improvement was a trench dug a couple of feet deep, in which was built what amounted to a low stone wall. This was ex tended a foot or so above grade level and the cabin rested on a more or less solid foundation. Today, though, our building styles and standards, not to mention building codes, demand a more stable and substantial foundation under our houses.

There are a number of different kinds of foundations that are suitable for log houses, and no one is markedly better than another. Any of them will do the job, and selection rests upon local building codes, house design, building site conditions, and personal preferences.

TYPES

You have five basic options as far as foundation types are concerned, and you can use any combination of them beneath different parts of the house if that seems desirable.

The first and simplest variety is the open foundation in which the building rests upon a series of piers, piles, or posts spaced around the perimeter of the building and at certain interior points. The structure might be only 6 inches or so above grade level (not recommended because of lack of access) or might be elevated to a height of 3 or 4 feet or even more, with free air movement beneath the building. This style is not widely used for houses, mainly because of appearance, but is sometimes used for summer cottages, hunting camps, and storage buildings. The system is widely used for deck and porch support, too, especially those that extend out over a steep drop-off. This is the only foundation style that obviates any possibility of the buildup and infiltration of radon gasses into the structure.

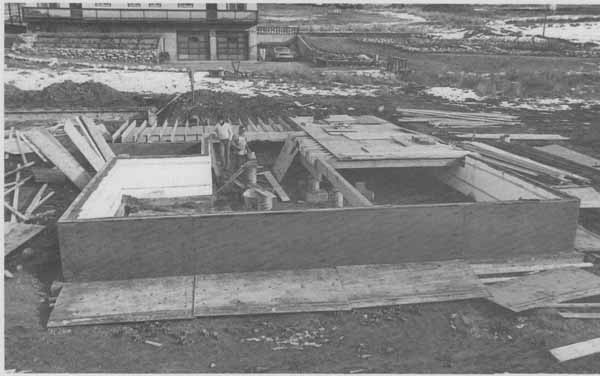

Fig. 4-1. Pier foundation skirted with re-sawn boards on a framework.

The second style is a modification of the first, with the house (or parts thereof) set on piers. Instead of being completely open, all spaces between grade level and the structure proper are filled in with some sort of nonstructural trim material, thus forming a skirted foundation (Fig. 4-1). Again, the structure may be low to the ground or high enough to provide a sizable crawl space underneath.

This is a satisfactory arrangement which combines low cost with a neat and attractive appearance, while affording some extra, dry storage space. The skirting material can be nearly anything. Textured plywood attached to a framework is often used, as is corrugated or patterned sheet metal roofing. Latticework was once very popular for this purpose and is still used to some extent. Other possibilities include stonework, planking, brick or imitation brick, and decorative concrete block. With complete skirting, provisions must be made for ventilating the area so as to prevent moisture buildup. This can be done by installing wood or metal louvers, sections of latticework, gratings, or other types of vents in the skirting. However, neither ground moisture nor surface water run off poses much of a problem for the foundation system itself (as is also true of the open foundation).

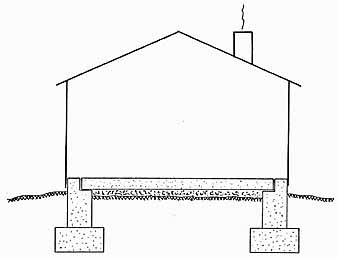

The third choice is a continuous-wall crawl space arrangement, which is today per haps the most popular of all. In this type of construction a continuous wall is built around the perimeter of the structure, extending from a below-grade level at or slightly below frostline (usually about 2 to 4 feet deep but not less than 18 inches) to any suitable height above grade level (Fig. 4-2). The bottom of the house itself might be only a few inches above grade, or in some instances 3 feet or more. Or the distance can be varied all around the house by stepping the foundation. The continuous wall supports all the weight of a small structure, while in larger structures a portion of the weight is borne by girders, piers, or other support arrangements beneath the floor. The foundation may be made of poured concrete, concrete blocks, stone, brick, a specially treated wood foundation system, or various combinations of materials. As with the skirted foundation, suitable ventilation has to be provided to pre vent moisture buildup.

Fig. 4-2. Note the piers for girder support used in conjunction with

this typical continuous-wall crawl-sp foundation.

The fourth possibility is a full basement, and there are two varieties to consider. The choice of one or the other rests to a great degree on the topography of the building site and the design of the house. One type is the hole- in-the-ground basement, made by excavating to a depth of anywhere from about 5 to 8 feet over the entire area of the building footprint (the specific, outlined area that the building will cover when constructed). Then full-height walls are built around the perimeter of the structure, or that portion that will lie above a full basement. The foundation may rise to just above grade level, go up 2 or 3 feet, or be variably stepped. Some foundations contain no windows, while others can have small ones either exposed between grade level and the foundation top or set in wells sunk into the ground alongside the foundation walls. By far the greater proportion of the foundation is under ground on all sides of the house.

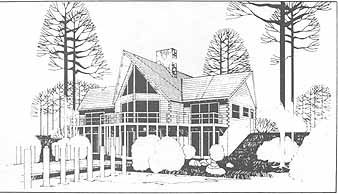

The other variety, a daylight or walk-in basement (also sometimes called a “garden level”), contains one or more walls that are al most or entirely exposed and above grade level (Fig. 4-3), an arrangement satisfactory on steeply sloping sites. Though these basements are built in essentially the same way and sup port the perimeter of the house, the exposed walls are fitted out with doors and windows and finish exterior siding, and from at least one direction actually become ground-level floors.

Fig. 4-3. Any log house can be built on top of a daylight basement

to gain an added level of living quarters.

Full basements of either type are most often built from poured concrete or concrete block. The exposed wall portions may be constructed of the same materials, or framed up with wood, or otherwise built in the same manner as the rest of the above-ground structure. Exposed masonry walls can later be veneered with brick, stone, or other building materials. Another possibility for constructing full basement walls is the Permanent Wood Foundation (PWF) system, which is rapidly gaining acceptance throughout the country. Stone and brick have also been used in the past for this purpose, but seldom are anymore.

And last, you might choose to build your house on a slab foundation (Fig. 4-4). Slab foundations are made entirely from concrete poured onto a previously prepared surface, which is approximately at grade level. As with all foundations, this style has its advantages and disadvantages, and is a particularly popular method in the more temperate parts of the country. It can be successfully used, however, in any climate, and often forms an integral part of solar house designs.

Fig. 4-4. A typical slab foundation arrangement.