AMAZON multi-meters discounts AMAZON oscilloscope discounts

PLANNING GROUP

Typically, the maintenance organization benefits from a planning group. There are different groups of craftsmen (e.g., millwrights, electricians, stores personnel, and support personnel) whose activities must be coordinated for the maintenance department to be most effective. Maintenance supervisors are needed to direct the current efforts of the personnel and seldom have the time available to plan properly the work to be done. A person or group of persons, depending upon the size of the maintenance department, should do the planning function.

Maintenance planning is a mechanism within the maintenance department for coordinating the work to be assigned. It is the maintenance planning group's responsibility to plan all maintenance work, except that needed during emergency breakdowns.

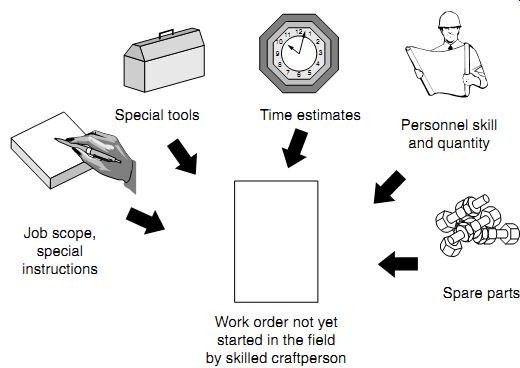

After a work order is written requesting the services of the maintenance department, planning goes into action. A maintenance planner takes the work order and does preparatory planning for the crew supervisor and craftsmen who will ultimately execute the work. The planner considers the proper scope of work for the job, for example, the work requester may have identified a noisy valve. The planner determines whether the valve should be patched or replaced and identifies the materials needed for the specified job and their availability. If the material is not on hand, the planner, working with the maintenance supervisor, determines how quickly it is needed. When the stores personnel advise the planner that the part has been received, the job may be scheduled. In addition, the planner specifies the appropriate craft skills for the job. Having these determinations made before the crew supervisor assigns a job for execution helps avoid problems such as delays caused by having assigned a person with insufficient craft skills or from not having all the required materials.

Having time estimates also allows crew supervisors to judge how much work to assign and thus better control the work in the sense that supervisors have expected completion times and can work to resolve any problems that might interfere with the schedule.

The planners help the stores and purchasing personnel ensure that there is proper inventory control. Planners can advise which stock parts should be checked for turnover on a regular basis. Then minimum and reorder quantities may be kept up for functional use without having unnecessarily high inventories.

Consequently, maintenance planning brings together or coordinates the efforts of many maintenance activities, including craft skills and knowledge, labor and equipment availability, materials, tooling, and equipment data and history.

THE VALUE OF A PLANNING PROGRAM

The value of a preventive maintenance program is well known. However, planned maintenance in the context of this section is not preventive maintenance. Preventive maintenance (PM) consists of a frequency-based set of routine maintenance activities designed to prevent equipment problems.

Examples of PM actions include regular equipment inspections and proper lubrication. Preventive maintenance work is planned ahead of time, and the work orders specify a planned set of procedures to execute. Thus, one might consider PM as "planned maintenance." Nevertheless, it is important to note that planned maintenance consists of much more than PM tasks. The planning group plans all work requested by plant personnel except for emergency jobs. The planning consists of the preparatory work needed to help the plant maintenance crew execute the work order more effectively and efficiently. [In the case of an emergency breakdown, the planner can also help. He can quickly search, especially if the maintenance department has a computerized maintenance management system, for previous work done on similar jobs. This will allow him to get the parts and other information to the personnel already working on the breakdown, and thus minimize the disruption to both the maintenance and operating departments.] See FIGURE 1.

FIGURE 1 Planner adds information.

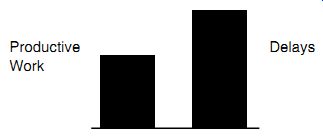

FIGURE 2 Reality: Industry average for wrench time = 25-30 percent.

The Objective

The primary objective of maintenance planning is to increase craftsmen's wrench time. Wrench time refers to the relative amount of time in which a craftsman productively works on an assigned job versus the amount of time spent in travel, preparation, and delays. Examples of delays are time spent obtaining material, tools, or instructions, or even traveling or being on break time. Contrary to common perception, delays account for the overwhelming vast majority of a craftsman's time.

Not even considering administrative time such as vacation or training, delays account for 65 to 75 percent of the time spent on the job by the typical craftsman. This means that out of a 10-hr shift, the average person only spends 2 1/2 to 3 1/2 hr productively working on a job. This average person spends the other 6 1/2 to 7 1/2 hr on "nonproductive" activities such as waiting at the parts counter, traveling to obtain a special tool, receiving job instructions from a supervisor, or waiting to be assigned another job. It is true that craftsmen must engage in these nonproductive activities in order to complete the assigned maintenance work, say rebuilding a pump. Nevertheless, industry designates these delay activities as nonproductive because whether or not they are avoidable, they truly delay the real work of performing maintenance actions directly on plant equipment. There is a common perception that delays do not consume significant portions of time; statistically valid observational studies prove otherwise. A few moments here gathering instructions and a few moments there waiting for a job assignment really add up fast. See FIGURE 2.

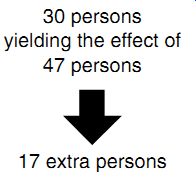

Limiting these nonproductive activities offers a tremendous opportunity for advancing maintenance productivity. Maintenance planning, by anticipating probable delays and planning around them, should reduce delays to as little as 45 percent of the typical craftsman's time. That means that average craft wrench time should improve to 55 percent from the previous best of 35 percent experienced by good maintenance organizations without a formal planning function. (In analyzing the wrench time for maintenance personnel, one must be aware that craftsman time spent in preventive and predictive maintenance inspections is considered wrench time. Indeed, this inspection activity may well be the most productive time spent by the personnel, especially if the inspections result in finding a potential breakdown, and the problem is fixed before breakdown occurs.) Are these numbers significant? They certainly are. A maintenance force of only 30 persons delivers the effect of a 47-person workforce with the addition of a single maintenance planner. Consider three persons working at 35 percent wrench time. Their total productive time is 3 times 35 percent, or 105 percent. If one of these persons was made to be a planner, that person's individual wrench time would be 0 percent since a planner only prepares for, but never directly performs, maintenance work. On the other hand, the planner helps boost the wrench time of the two remaining craftsmen because they then spend less time in delay areas because materials and assignments are ready to go.

Their wrench time rises to 55 percent each, for a total of 110 percent, which roughly breaks even with the 105 percent of three persons working without planning assistance. The great leverage in planning becomes apparent when using a single planner to plan for 20 to 30 craftsmen. Thirty per sons leveraged from 35 percent wrench time to 55 percent wrench time can achieve the effect of 47 persons as follows:

30 persons __ 47 persons

55% new wrench time

___ 35% old wrench time

This equivalent addition of 17 extra persons to the workforce for the price of one planner can be valued simply as the worth of their salaries. For example, 16 persons _ $25/hr (including all benefits) _ 2080 hr/year _ $832,000 annually Yet the real monetary worth to the company is often the increased equipment availability and efficiency due to maintenance work being completed more quickly. Such increased equipment performance often allows deferment of capital investments for otherwise needed new capacity. The increased maintenance productivity also often allows the existing maintenance force to be able to maintain an increased amount of equipment without hiring when the company does add new capacity.

FIGURE 3 Maintenance planning can reduce delays to improve wrench time.

The above calculations using 2080 hr/year indicate that planning focuses on coordinating and improving day-to-day, routine maintenance. It is not surprising that wrench time studies point to the maintenance effort expended on a daily basis in the absence of outages as the prime candidate for improvement in productivity. Plants typically prepare for and execute major outages with much greater efficiency than they do routine maintenance chores. Plants often view daily maintenance chores as so routine that they do not suspect them as having such potential for betterment. See FIGURE 3.

Industry Results and Experience

Industry has long been familiar with formal maintenance planning, but mostly with the frustration in its application. Planners in these instances became rapidly bogged down in planning every job from scratch and in providing overly detailed procedures for the maintenance execution. As a result, work crews often could not afford to wait on the planners, especially for more urgent jobs and ended up working mostly unplanned assignments.

Enlightened planners who have achieved their goals of improving craft wrench time have learned not to plan every job with the same planning approach. These planners actually spend less time on more urgent jobs. On urgent jobs, planners quickly scope the job and assign time estimates without any attempt at devising intricate job procedures. These planners know that the craftsmen mostly need a head start with job scope and the crew supervisors mostly need time estimates to control the work.

Although planner assistance with material, tool, and special instruction identification is valuable, it has become apparent that the primary value in planning assistance is its provision of time estimates for schedule control. This coordination tool for managers has allowed them to help crew members focus on performing 40 hr of work each week instead of focusing solely on completing urgent maintenance tasks. The improvement of wrench time helps crews complete those less urgent tasks well before they become urgent.

When maintenance planning is used properly, plants have seen dramatic initial drops in the backlog of work orders. In 2 months, one east coast power station totally cleared a mechanical back log with work orders in it as much as 2 years old. This station was able to assist two other nearby stations in the same utility with its resulting excess labor force. These type of plants have then been able to focus on generating a new type of work order, one more proactive or preventive in nature to head off future maintenance problems and thus increase equipment availability. In the past, plants often neglected this type of work as they struggled to complete only the most visible, reactive tasks to keep units from shutting down and losing immediate availability and production capability.

A final note from industry experience suggests that because planning pushes so hard for productivity, a workforce quality focus must first be in place. Completing more work orders quickly and efficiently, but without regard for quality, must never assume primary importance. Nonetheless, because the work force does accomplish more work, the craftsmen have more time to complete those particular troublesome jobs properly. Therefore, frequently planning itself promotes quality. (One should note that any maintenance job, properly completed, is, in itself, a form of preventive maintenance.) In addition, planning helps provide the correct materials and tooling for jobs and helps use file information to avoid problems encountered on similar past jobs. These preparatory efforts tend to promote better quality in the execution of work orders.

Selling the Planning Program to Management

Maintenance managers and supervisors attempting to convince plant or company management to implement maintenance planning must speak in financial terms. Upper management must see the program in terms of the bottom line that keeps the plant more productive and profitable. Upper management must not see the program as simply promoting a craftsman out of the work force to another administrative role at a higher salary. The predominant low wrench time in industry that occurs when there is not proper planning of maintenance activities and common misunderstanding must be explained.

Another factor favoring the creation of a planner position is the maintenance of plant work order records. Without proper records, plant managers cannot make intelligent decisions for repairing or upgrading plant equipment. Plant managers may know how much an improved model of a pump would cost, but often have no idea of the cost of maintenance on the old pump over the last several years. Planner files and records help remedy this situation. For example, whereas the new pump costs $5000, the planning group's files of past work orders might reveal that the plant routinely spends $3000 each year on maintenance that should be avoided with the new pump. Information is powerful and profitable, but only if available when needed. When selling planning to management, the proponents should focus on the planning function's ability to "increase the work force without hiring" and its ability to utilize equipment information for better plant financial decisions.

WHAT IS MAINTENANCE PLANNING?

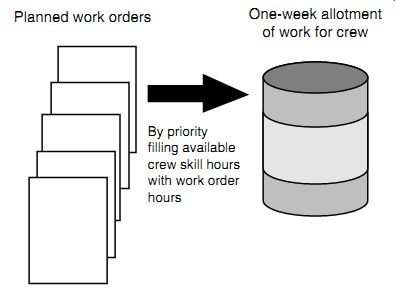

By definition, planning occurs before craftsmen begin actual work execution. A maintenance-planning group receives a work order for planning as soon as possible after any required initial plant authorization process. The planners simply perform a number of preparatory tasks such as identifying or even reserving parts in a storeroom to make the job ready to be worked. The planners anticipate and try to head off probable delays for the job. Their efforts create what can be called "planned work orders." The planners (or a scheduler within the planning group) also create a 1-week schedule for each work crew. This helps the crew supervisors recognize all the appropriate jobs that should receive attention that week according to the plant priority system. This scheduling effort also pro vides a goal for productivity.

Planned work orders are available to the crews to select as needed, and the scheduler delivers scheduled work orders to the crew on a weekly basis. (Daily or shift scheduling is left to the crew supervisor.)

How to Plan Work

A planner first reviews all the newly received work orders to determine which ones merit first attention. A planner must first quickly plan all reactive or otherwise urgent work orders so as not to delay crews that must begin their execution.

Selecting a number of reactive work orders, a planner would look in the plant files to see if similar problems have been identified and worked on in the past. The plant files are established on a one-to-one basis with the equipment. Each piece of equipment previously receiving maintenance during the regime of planning will have a corresponding specific, component-level file containing all past work orders. These files are arranged numerically by the equipment number. (Each piece of equipment is labeled with a plant-specific identification number, usually called an asset number.) A computerized maintenance management system (CMMS) would similarly hold an electronic file based on this equipment number revealing past work orders. (When a work order comes in for a piece of equipment that does not have a maintenance history, a file will be created by the planner later that day after he completes the pertinent job plan.) The value of the files cannot be overlooked.

Maintenance crews work on the same pieces of equipment repeatedly. The crews may not recognize this cycle of maintenance because they have many different ongoing tasks and frequently different persons are assigned to the different instances of work on the equipment. Nevertheless, the same almost identical maintenance jobs are repetitious and files offer good learning curves of continuing improvement opportunities when consulted. Once a craftsman identifies a particular spare part as vital to the repair of a valve, the hunt for the identity of the part need never be repeated. Sadly, most jobs are worked from scratch or planned from scratch without using any of this helpful file information.

Creating component-level files to allow rapid retrieval of information and giving the planners clear responsibilities as file clerks within the maintenance organization resolves this impediment to maintenance efficiency. On a reactive job, the rule of thumb should be that if no component-level file information already exists, the planner has no time to conduct other research to find more information. The field technician will have to find such information if needed and hopefully provide feedback for the file to help with future jobs.

The planners utilize their own considerable craft experience and site visits in addition to any file information to determine quickly proper job scopes and probable parts and special tools needed. The planners may also include special instructions not commonly or immediately apparent to regular craft technicians. The planners respect the skills of the craft technicians and, even on less urgent jobs, do not attempt to provide detailed job steps on most routine maintenance tasks. That would unduly slow the planners and provide job details not needed (or even resented) by skilled technicians. The planners, working for many technicians, prefer to be file clerks and faithfully reissue information the technicians have learned on previous jobs. For a reactive work order, the planner identifies the minimum craft skill necessary and estimates the time it should take a good technician to complete the job if there are no unanticipated delays.

The planner writes down the necessary information determined in the planning section of each work order and sends it to a waiting-to-be-scheduled file accessible to the crew supervisors. The planner also reserves anticipated spare parts in the storeroom if needed to ensure their later availability.

The planner then turns his attention to any unplanned, less reactive work orders. The planner can spend more time if necessary on these work orders because the plant and the maintenance crews place little pressure on their rapid completion. On such proactive jobs, if no component-level file information already exists, the planner has some time to do research to find more information. The planner may consult vendor catalogs, call manufacturers, or review other available technical literature.

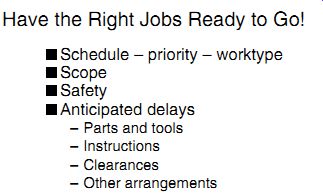

Whenever the planner uncovers helpful information for a piece of equipment, the planner transfers a copy of it to that equipment's component-level file. Otherwise, the planner completes planning proactive work orders in the same manner as for other work orders. See FIGURE 4.

Planners classify many jobs in maintenance as "minimum maintenance," hardly worth the time of someone to plan them. These jobs may consist of moving barrels from one end of the plant to another, cleaning a burner deck, or some other task requiring few hours to complete and with no historical value. Planners should still "plan" these jobs, but only by clarifying job scopes, specifying craft skill, and estimating times in rapid fashion.

--------------

Schedule - priority - worktype

Scope

Safety

Anticipated delays

- Parts and tools

- Instructions

- Clearances

- Other arrangements

FIGURE 4 Planning proactive work orders.

--------------

FIGURE 5 Scheduler allocates work orders.

How to Schedule Work

Advance scheduling of routine maintenance is done one week at a time in the planning group. Overall plant priorities should not change too much over one week. Scheduling simply involves matching up available crew labor hours with backlogged job hours. Scheduling may be done by any planner or by a designated scheduler within the planning group. Near the end of each week, each crew gives the scheduler a forecast of the amount of hours each crew skill should be available for the next week. For example, a crew might forecast having 200 first-class mechanic hours and 100 second-class mechanic hours available. The crew first subtracts any vacation or training hours as well as expected hours needed to complete already in-progress work that will carry over into the subject week. The scheduler then systematically (by priority) fits the backlogged planned work orders into the crew labor hours forecast. Jobs previously planned for the lowest possible skill level give a scheduler the most flexibility when selecting work. For example, a portion of the first-class mechanic hours might be matched with some high priority work that was planned as only needing a less skilled, second-class mechanic. The scheduler finishes allocating the backlog when the crew hours are full. In the above crew case, the schedule would be set when the crew has been allocated 200 hr of planned work that a first-class mechanic could accomplish and 100 hr that a second-class mechanic could accomplish. These allocated work orders are then considered scheduled and are delivered to the respective crew supervisor. See FIGURE 5.

During the subsequent scheduled week, the crew supervisor draws from the package of scheduled work orders as the week progresses. The scheduler has not assigned any particular work order to any particular day of the week or craftsman. Particular job assignments and daily scheduling fall entirely within the realm of the crew supervisor. This person is best suited for personnel assignment and following the progress of individual jobs. Planned time estimates for particular jobs vary widely in accuracy, only becoming valid over an entire week's time as some jobs finish early and others finish late. The crew supervisor also has the ability to assign work that is not in the scheduled allotment.

The crew supervisor is only accountable to the manager of maintenance to discuss the completion of the week's allotted work. The planning group tracks schedule compliance by giving the crew super visor credit for all hours on jobs started. The primary management concern would be to verify if the crew supervisor has valid reasons for not starting a majority of the allotted work orders for the week.

A secondary management concern would be if the carryover work forecasted each week becomes higher than the available hours for which to schedule or allot work.

HOW TO IMPLEMENT THE PLANNING PROGRAM

As mentioned previously, a single planner can plan for 20 to 30 craftsmen. Yet the placement of the planner's responsibility within the organization and the degree of management support both make critical differences to the success of the program. In addition, the careful selection of only well-qualified persons to be planners makes a critical difference.

Organization

First, without a doubt, the planner must be placed outside the control of an individual crew super visor. Crew supervisors frequently find themselves in reactive situations where only additional labor power can help. It would be only too natural for a supervisor to "borrow" a planner "working on future stuff" to help temporarily. Industry experience shows these planners soon stop planning, and become fixtures on crews using their craft skills instead of their planning skills.

Planners must report directly to the superintendent over the crew supervisors and should be in a position where they can relate on a peer basis with the first-line crew supervisors. The planners deal more with the crew supervisors than the technicians, and this is an appropriate organization position.

Second, although one planner can plan for 20 to 30 persons, the maturity and complexity of the maintenance organization may indicate the lower figure of 20 works best. If planning is new, 20 would be more appropriate. Some knowledgeable persons recommend a 1 to 15 ratio. In any case, remember that 3 craftsmen provide a break-even point. Any maintenance organization with more than 5 craftsmen should consider converting one position to a planner position.

Third, mechanical maintenance appears to be one of the best fits for planning because the actual maintenance time often dwarfs any troubleshooting time. In crafts such as electrical maintenance where troubleshooting may be a significant portion of any job, planners may be less desirable or desirable in lower ratios of craftsmen to planner. The scoping aspect of planning may be minimized in some of these circumstances, but even then, the repetitious nature of maintenance work often makes the documentation aspect of planning invaluable. In some plants where the bulk of the maintenance work is mechanical, only mechanical work is formally planned, but that work is closely coordinated with the support electricians and other crafts.

Selecting Personnel

The success of the maintenance-planning program rests with the initial selection of planners. A planner must be a respected craftsman, highly competent with hands-on maintenance skills, and at the same time very good with data analysis and people skills. He must be able to correctly deter mine the scope of an equipment problem and be able to find and apply information from equipment manuals and from past problems identified in file records. The planner must also be able to work with a variety of persons from the plant manager to the new apprentice as well as with vendors and manufacturers.

Management must choose this person carefully because the wrong person cannot make the sys tem work. Guidelines for planning can be set, but modern maintenance offers too many variables to dictate the actions of an effective planner by a rigid set of procedures. The planner will coordinate a multitude of expensive maintenance resources for the greatly improved productivity of the entire maintenance force. Many of the requirements for this job match those of promoting and hiring crew supervisors. Management must choose planners as carefully as it does new supervisors with corresponding wages. Compensation should not be a stumbling block. From the earlier calculation, a single planner is worth 17 craftsmen.

Communication and Management Support

Obviously planning introduces major changes into the maintenance organization. Management must communicate its support of planning by giving the planner an appropriate role and position in the group. Management must explain the concepts of repetitive maintenance and the value of documentation and file information to all personnel. The technicians themselves will collect information that the planner will file as job feedback. The planners will not necessarily plan each job from scratch.

Management desires the planning function to give field technicians a head start and to give the crew supervisors better schedule control.

The introduction to this section mentioned the importance of coordination in maintaining an effective organization. Yet, one more aspect must be considered. Many managers err in disbanding many of the coordinating portions of an organization as it matures. That is, these managers feel that experienced specialized areas of the company should learn how to coordinate with each other and that many persons performing only coordinating roles are no longer needed. They feel that these coordinating roles were mostly useful in initially establishing the efforts of the craftsmen. This questionable notion can be carried to an extreme. Industry frequently sees the devastation of organization effectiveness caused by the unwitting removal of a clerk "just doing paperwork" or of a supervisor when two crews are combined. As organizations continue to require specialized functions, they continue to require coordination. Coordination roles mature along with the rest of the organization under enlightened management to provide vital functions. Similarly, the maintenance planning function will continue to be a vital function as the craft crews become accustomed to receiving work orders with lists of materials and time estimates. If done properly, the planning function will be properly integrated into the overall maintenance function. For example, the craftsmen will find that they are not being punished for taking longer than the allotted time to complete a job. They will be asked to notify planning of the problems experienced so that the planner can take these factors into account the next time similar work is scheduled. This cooperation will result in better scheduling and will maximize the overall efficiency of the maintenance work.

REPORTING SUCCESSFUL RESULTS TO MANAGEMENT

Maintenance managers use the following general areas to track the results of planning and to report to upper management. First, the maintenance planning and scheduling effort should result in an increased quantity of completed work per week and thereby a reduction in the backlog of maintenance work orders. In the past, writers of work orders probably knew that the maintenance group would only address somewhat urgent work orders. So, these persons would not bother to identify other types of work. Now, the need to identify this work becomes obvious because the maintenance force has geared itself to address all requested work.

Second, since planned work is more efficient than unplanned work (because the planners make sure that all parts, tools, instructions, etc., are available before the job is started), management desires to see that work hours are spent mostly on properly planned jobs.

Third, due to better planning and completion of jobs, the backlog of high-priority work will decrease. Maintenance personnel will have more time to spend on project work and other required, but lower-priority, jobs. This also keeps low-priority jobs from being put off until they become emergencies. Coupled with preventive and predictive maintenance inspections, most emergency work will disappear.

Fourth, and with a longer-range focus, upper management should be apprised of the ability of the maintenance force to handle either plant growth or attrition without hiring. Management must have this information to establish adequate future staffing plans whether they are for capital expansion or hiring of new apprentices or technicians.

Fifth, and perhaps most important, maintenance planning should favorably impact plant production availability. So many different plant programs or efforts impact overall plant equipment avail ability; it is difficult to ascribe improvement to any one factor. Did plant production capability rise because of planning or because of having a better storeroom? Is it because of planning or better supervision or because of planning or better craft training or hiring? Close attention to plant activities and plant availability should be tracked as the maintenance force implements maintenance planning of work orders. In any case, management should be reminded that planning performs a vital role in the coordination of all areas of maintenance for the continued preservation and improvement of availability.

PREV | NEXT | Article Index | HOME