AMAZON multi-meters discounts AMAZON oscilloscope discounts

Production/Maintenance Cooperation:

Some organizations, such as General Motors' Fisher Body Plant, have established the position of Production/Maintenance Coordinator. This person's function is to ensure that equipment is made available for inspections and preventive maintenance at the best possible time for both organizations. This person is a salesman for maintenance.

This is an excellent developmental position for a foreman or supervisor. One year in that position will probably be enough for most people to learn the job well and to become eager to move on to duties with less conflict.

Other organizations make production responsible for initiating a percentage of work orders. At Frito-Lay plants , for example, the production goal is 20 percent. This target stimulates both equipment operators and supervisors to be alert for any machine conditions that should be improved. This approach tends to catch problems before they become severe, rather than allowing them to break down. The results appear to be better uptime than in plants where a similar situation does not occur.

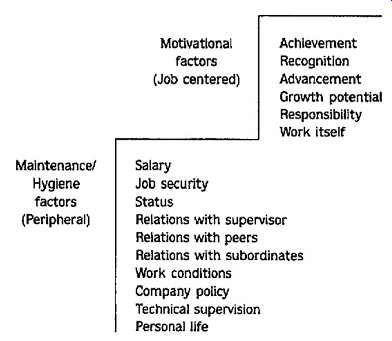

FIG. 5 Two-factor theory of motivation.

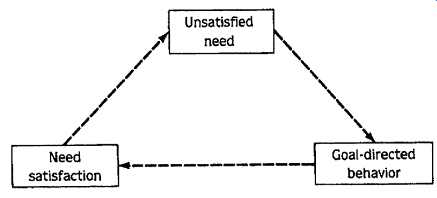

FIG. 6 The process of motivation.

Effectiveness:

Productivity is made up of both time and rate of work. Many people confuse motion with action. Utilization, which is usually measured as percentage of productive time over total time, indicates that a person is engaged in a productive activity. Drinking coffee, reading a newspaper, and attending meetings are generally classed as nonproductive. Hands-on maintenance time is classed as productive. What appears to be useful work, however, may be repetitious, ineffective, or even a redoing of earlier mistakes.

A technical representative of a major reprographic company was observed doing preventive cleaning on a large duplicator. He spread out a paper "drop cloth" and opened the machine doors. The flat area on the bottom of the machine was obviously dirty from black toner powder, so the technical representative vacuumed it clean. Then he retracted the developer housing. That movement dropped more toner, so he vacuumed it. He removed the drum and vacuumed again. He removed the developer housing and vacuumed for the fifth time. On investigation, it was found that training had been conducted on clean equipment. No one had shown this representative the "one best way" to do the common cleaning tasks. This lack of training and on-the-job follow up counseling is too common! To be effective, we must make the best possible use of available time. There are few motivational secrets to effective preventive maintenance, but these guidelines can help:

1. Establish inspection and preventive maintenance tasks as recognized, important parts of the maintenance program.

2. Assign competent, responsible people.

3. Follow up to ensure quality and to show everyone that management does care.

4. Publicize reduced costs with improved uptime and revenues that are the result of effective preventive activities.

Total Employee Involvement:

If the only measure of our performance were the effort we exerted in our day-to-day activities, life would be simpler. Unfortunately, we are measured on the performance of those who work for us, as well as on our own effectiveness. As supervisors and managers, our success depends more on our workforce than on our own individual performance. Therefore, it’s essential that each of our employees consistently performs at his or her maximum capability. Typically, employee motivation skill is not the strong suit of plant supervisors and managers, but it’s essential for both plant performance and success as a manager.

By definition, motivation is getting employees to exert a high degree of effort on their jobs. The key to motivation is getting employees to want to consistently do a good job. In this light, motivation must come from within an employee, but the supervisor must create an environment that encourages motivation on the part of employees.

Motivation can best be understood using the following sequence of events: needs, drives or motives, and accomplishment of goals. In this sequence, needs produce motives, which lead to the accomplishment of goals. Needs are caused by deficiencies, which can be either physical or mental. For instance, a physical need exists when a person goes without sleep for a long period. A mental need exists when a person has no friends or meaningful relationships with other people. Motives produce action.

Lack of sleep (the need) activates the physical changes of fatigue (the motive), which produces sleep (the accomplishment). The accomplishment of the goal satisfies the need and reduces the motive. When the goal is reached, balance is restored.

Employee Needs. All employees have common basic needs that must be addressed by the plant or corporate culture. These needs include the following:

Physical needs are the needs of the human body that must be satisfied in order to sustain life. These needs include food, sleep, water, exercise, clothing, shelter, and the like.

Safety needs are concerned with protection against danger, threat, or deprivation. Because all employees have a dependent relationship with the organization, safety needs can be critically important. Favoritism, discrimination, and arbitrary administration of organizational policies are actions that arouse uncertainty and affect the safety needs of employees.

Social needs include love, affection, and belonging. Such needs are concerned with establishing one's position relative to that of others. They are satisfied by developing meaningful personal relations and by acceptance into meaningful groups of individuals. Belonging to organizations and identifying with work groups are ways of satisfying the social needs in organizations.

Esteem or ego needs include both self-esteem and the esteem of others. All people have needs for the esteem of others and for a stable, firmly based, high evaluation of themselves. The esteem needs are concerned with developing various kinds of relationships based on adequacy, independence, and giving and receiving indications of self-esteem and acceptance.

Self-actualization or self-fulfillment is the highest order of needs. It’s the need of people to reach their full potential in terms of their abilities and interests.

Such needs are concerned with the will to operate at the optimum and thus receive the rewards that are the result of doing so. The rewards may not be economic and social but also mental. The needs for self-actualization and self fulfillment are never completely satisfied.

Recognizing Needs. Every supervisor knows that some people are easier to motivate than others. Why? Are some people simply born more motivated than others? No person is exactly like another. Each individual has a unique personality and makeup.

Because people are different, different factors are required to motivate different people. Not all employees expect or want the same things from their jobs. People work for different reasons. Some work because they have to work; they need money to pay bills. Others work because they want something to occupy their time. Still others work so they can have a career and its related satisfactions. Because they work for different reasons, different factors are required to motivate employees.

When attempting to understand the behavior of an employee, the supervisor should always remember that people do things for a reason. The reason may be imaginary, inaccurate, distorted, or unjustified, but it’s real to the individual. The reason, what ever it may be, must be identified before the supervisor can understand the employee's behavior. Too often, the supervisor disregards an employee's reason for a certain behavior as being unrealistic or based on inaccurate information. Such a supervisor responds to the employee's reason by saying, "I don't care what he thinks-that's not the way it is!" Supervisors of this kind will probably never understand why employees behave as they do.

Another consideration in understanding the behavior of employees is the concept of the self-fulfilling prophecy, known as the Pygmalion effect. This concept refers to the tendency of an employee to live up to the supervisor's expectations. In other words, if the supervisor expects an employee to succeed, the employee will usually succeed.

If the supervisor expects employees to fail, failure usually follows. The Pygmalion effect is alive and well in most plants.

When asked the question, most supervisors and managers will acknowledge that they trust a small percentage of their workforce to effectively perform any task that is assigned to them. Further, they will state that a larger percentage is not trusted to perform even the simplest task without close, direct supervision. These beliefs are exhibited in their interactions with the workforce, and each employee clearly under stands where he or she fits into the supervisor's confidence and expectations as individuals and employees. The "superstars" respond by working miracles and the "dummies" continue to plod along. Obviously, this is no way to run a business, but it has become the status quo. Little, if any, effort is made to help underachievers become productive workers.

Reinforcement. Reinforced behavior is more likely to be repeated than behavior that is not reinforced. For instance, if employees are given a pay increase when their performance is high, then the employees are likely to continue to strive for high performance in hopes of getting another pay raise. Four types of reinforcement- positive, negative, extinction, and punishment-can be used.

Positive reinforcement involves providing a positive consequence because of desired behavior. Most plant and corporate managers follow the traditional motivation theory that assumes money is the only motivator of people. Under this assumption, financial rewards are directly related to performance in the belief that employees will work harder and produce more if these rewards are great enough; however, money is not the only motivator. Although few employees will refuse to accept financial rewards, money can be a negative motivator. For example, many of the incentive bonus plans for production workers are based on total units produced within a specific time (i.e., day, week, or month). Because nothing in the incentive addresses product quality, production, or maintenance costs, the typical result of these bonus plans is an increase in scrap and total production cost.

Negative reinforcement involves giving a person the opportunity to avoid a negative consequence by exhibiting a desired behavior. Both positive and negative reinforcement can be used to increase the frequency of favorable behavior.

Extinction involves the absence of positive consequences or removing previously provided positive consequences because of undesirable behavior. For example, employees may lose a privilege or benefit, such as flextime or paid holidays, that already exists.

Punishment involves providing a negative consequence because of undesirable behavior. Both extinction and punishment can be used to decrease the frequency of undesirable behavior.

Discipline:

Discipline should be viewed as a condition within an organization where employees know what is expected of them in terms of rules, standards, policies, and behavior.

They should also know the consequences if they fail to comply with these criteria.

The basic purpose of discipline should be to teach about expected behaviors in a constructive manner.

A formal discipline procedure begins with an oral warning and progresses through a written warning, suspension, and ultimately discharge. Formal discipline procedures also outline the penalty for each successive offense and define time limits for maintaining records of each offense and penalty. For instance, tardiness records might be maintained for only a six-month period. Tardiness before the six months preceding the offense would not be considered in the disciplinary action. Preventing discipline from progressing beyond the oral warning stage is obviously advantageous to both the employee and management. Discipline should be aimed at correction rather than punishment.

One of the most important ways of maintaining good discipline is communication.

Employees cannot operate in an orderly and effective manner unless they know the rules. The supervisor has the responsibility of informing employees of these rules, regulations, and standards. The supervisor must also ensure that employees understand the purpose of these criteria. If an employee becomes lax, it’s the supervisor's responsibility to remind him or her and if necessary enforce these criteria. Employees also have a responsibility to become familiar with and adhere to all published requirements of the company.

Whenever possible, counseling should precede the use of disciplinary reprimands or stricter penalties. Through counseling, the supervisor can uncover problems affecting human relations and productivity. Counseling also develops an environment of openness, understanding, and trust. This encourages employees to maintain self-discipline.

To maintain effective discipline, supervisors must always follow the rules that employees are expected to follow. There is no reason for supervisors to bend the rules for themselves or for a favored employee. Employees must realize that the rules are for everyone. It’s the supervisor's responsibility to be fair toward all employees.

Although most employees do follow the organization's rules and regulations, there are times when supervisors must use discipline. Supervisors must not be afraid to use the disciplinary procedure when it becomes necessary. Employees may interpret failure to act as meaning that a rule is not to be enforced. Failure to act can also frustrate employees who are abiding by the rules. Applying discipline properly can encourage borderline employees to improve their performance.

Before supervisors use the disciplinary procedure, they must be aware of how far they can go without involving higher levels of management. They must also determine how much union participation is required. If the employee to be disciplined is a union member, the contract may specify the penalty that must be used.

Because a supervisor's decisions may be placed under critical review in the grievance process, supervisors must be careful when applying discipline. Even if there is no union agreement, most supervisors are subject to some review of their disciplinary actions. To avoid having a discipline decision rescinded by a higher level of management, it’s important that supervisors follow the guidelines.

Every supervisor should become familiar with the law, union contracts, and past practices of the company as they affect disciplinary decisions. Supervisors should resolve with higher management and human resources department any questions they may have about their authority to discipline.

The importance of maintaining adequate records cannot be overemphasized. Not only is this important for good supervision, but it can also prevent a disciplinary decision from being rescinded. Written records often have a significant influence on decisions to overturn or uphold a disciplinary action. Past rule infractions and the overall performance of employees should be recorded. A supervisor bears the burden of proof when his or her decision to discipline an employee is questioned. In cases where the charge is of a moral or criminal nature, the proof required is usually the same as that required by a court of law (i.e., beyond a reasonable doubt).

Another key pre-disciplinary responsibility of the supervisor is the investigation. This should take place before discipline is administered. The supervisor should not discipline and then look for evidence to support the decision. What appears obvious on the surface is sometimes completely discredited by investigation. Accusations against any employee must be supported by facts. Supervisors must guard against taking hasty action when angry or when a thorough investigation has not yet been conducted.

Before disciplinary action is taken, the employee's motives and reasons for rule infraction should be investigated and considered.

Conclusions:

With few exceptions, employees are not self-motivated. The management philosophy and methods that are adopted by plants and individual supervisors determine whether the workforce will constantly and consistently strive for effective day-to-day performance or continue to plod along as they always have. As a supervisor or manager, it’s in your best interest, as well as your duty, to provide the leadership and motivation that your workforce needs to achieve and sustain best practices and world-class performance.

===

Work Order Costs

Included in Maintenance Budget

Excluded in Maintenance Budget

Production Support Non-periodic; Periodic Reactive Breakdown Repairs Preventive Tasks Corrective Repairs Predictive Tasks Skills Training Turnarounds/ Outages Improvements/ Modifications Regulatory Compliance Capital Projects Expense Projects R&D Product Testing Demonstrations Craftspersons, Supervisors, Planners, Managers Condition monitoring and advanced inspections Repairs, Rebuilds, Lubrication, Inspections, Adjustments Emergency Tasks

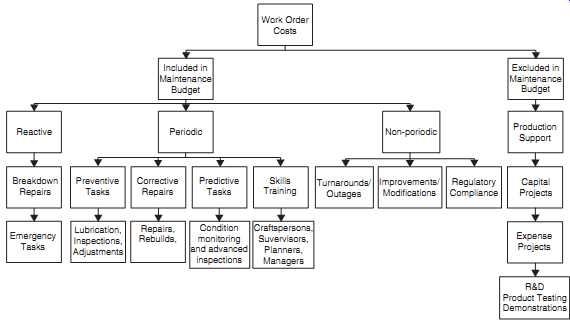

FIG. 7 G/L accounts cost matrix.

===

Record Keeping

The foundation records for preventive maintenance are the equipment files. The equipment records provide information for purposes other than preventive maintenance.

The essential items include:

• Equipment identification number

• Equipment name

• Equipment product/group/class

• Location

• Use meter reading

• Preventive maintenance interval(s)

• Use per day

• Last preventive maintenance due

• Next preventive maintenance due

• Cycle time for preventive maintenance

• Crafts required, number of persons, and time for each

• Parts required

FIG. 7 shows a typical accounts cost matrix developed for a SAP R-4 computerized maintenance management system (CMMS). The figure illustrates the major cost classifications and how they will be used to support the maintenance improvement process. Date collected in the eight "cost buckets" will be used to develop performance indicators, maintenance strategy, realistic maintenance budgets, and benchmark data.

Work Orders:

All work done on equipment should be recorded on the equipment record or on related work order records that can be searched by equipment. The equipment failure and repair history provide vital information for analysis to determine if preventive maintenance is effective. How much detail should be retained on each record must be individually determined for each situation. Certainly, replacement of main bearings, crankshafts, rotors, and similar long-life items that are infrequently replaced should be recorded. That knowledge is helpful for planning major overhauls both to deter mine what has recently been done, and therefore should not need to be done at this event, and for obtaining parts that probably should be replaced. There is certainly no need to itemize every nut, bolt, and light bulb.

Cost Distribution:

Maintenance improvement depends on the ability to accurately determine where costs are expended. Therefore, the SAP R-3 CMMS must be con figured to accurately capture and compile maintenance cost by type, production area, process, and specific equipment or machinery. This task is normally accomplished by establishing a work breakdown structure that will provide a clear, concise means of reporting expenditures of maintenance dollars. Within the SAP system, cost will be allocated into the following eight classifications:

• Emergency

• Maintenance

• Repair

• Condition monitoring and inspections

• Training

• Turnarounds/shutdown

• Improvements, modifications, and technical innovations

• Regulatory compliance

Emergency. All work performed in response to actual or anticipated emergency break downs, OSHA-reportable incidents, and safety-related repairs will be charged to the emergency classification. The intent of the maintenance improvement process is to eliminate or drastically reduce the percentage of time and cost associated with this type of work. In the SAP system, these tasks and activities will be assigned priority code 1.

Maintenance. As defined as, all activities performed in an attempt to retain an item in specified condition by providing systematic, time-based inspection and visual checks; any actions that are preventive of incipient failures. All work and actions are planned. Preventive maintenance tasks, such as inspections, lubrication, calibration, and adjustments, will be allocated to this cost classification. The intent of the maintenance improvement program is to increase the efforts in this classification to between 25 and 35 percent of total maintenance costs. In the SAP system, these tasks and activities will be assigned a priority code 6.

Repair. Includes all activities performed to restore an item to a specified condition, or any activities performed to improve equipment and its components so that preventive maintenance can be carried out reliably. All costs associated with repair, corrective maintenance, noncapital improvements, and rebuilds will be allocated to this classification. Examples of tasks include diagnostics, remediation of damage, and follow-up work and documentation. SAP priority codes 2, 3, or 4 will be assigned to these tasks.

Condition Monitoring and Inspections. The activities are defined as all activities involved in the use of modern signal-processing techniques to accurately diagnose the condition of equipment (level of deterioration) during operation. The periodic measurement and trending of process or machine parameters with the aim of predicting failures before they occur. Included in these activities are visual inspection, functional testing, material testing (all NDE/NDT), inspection, and technical condition monitoring. These tasks will be assigned SAP priority code 6.

Training. This cost center is defined as training provided to the maintenance workforce to enhance effectiveness. Examples of costs that should be allocated to this cost center include proactive maintenance, life-cycle cost, and total cost of ownership.

Turnarounds/Shutdowns. All activities required during a planned and scheduled temporary operating unit shutdown to maintain or restore operating efficiency, inspect equipment for purposes of mechanical or instrument/electrical integrity, and perform tests and inspections. Examples of activities that should be allocated to this cost center include major shutdowns and modifications of industrial systems and upgrading of buildings, steel structures, and pipeline systems. These tasks will be assigned an SAP priority code 5.

Improvements, Modifications, and Technical Innovations. All activities and measures taken to improve/optimize plant performance that are not carried out as a part of a project. This would include improvements relative to efficiency, availability, or safety improvements. Also included are improvement of plant technology, adaptation to current engineering requirements and regulations, and optimization of spare and replacement parts inventory.

Regulatory Compliance. Cost for the initial actions taken to achieve compliance with regulatory, safety, environmental, or quality requirements. For example, OSHA 1910.119, ISO 9000, FDA, Kosher, and others.

Cost Accounts Not Included in Maintenance and Repair. Some maintenance-related cost classifications may be omitted from the key performance indicators (KPIs) used to measure maintenance effectiveness. These omissions include the following:

• Production support. All activities required to support operations. These tasks and activities include connections, recommendations, retrofits, and cleaning work necessitated by operations, as well as opening and closing of equipment for filling, emptying, cleaning, and filter changes required for production.

• New investment. All activities required by in-house personnel to support capital equipment projects. These costs should be allocated to the appropriate project cost center.

• Improve existing assets. All activities required by in-house personnel to support expense projects. As in the case of capital projects, these costs should be allocated to the appropriate project cost center.

• Demonstrations. Follow the Corporate Capitalization Policy.

Special Concerns

Several factors can limit the effectiveness of maintenance. The primary factors that must be considered include (1) parts availability, (2) repairable parts, (3) detailed procedures, (4) quality assurance, (5) avoiding callbacks, (6) repairs at preventive maintenance, and (7) data gathering.

Parts Availability:

Parts to be used for preventive maintenance can generally be identified and procured in advance. This ability to plan for investment of dollars for parts can save on inventory costs because it’s not necessary to have parts continually sitting on the shelf waiting for a failure. Instead, they can be obtained just-in-time to do the job.

The procedures should list the parts and consumable materials required. The scheduler should ensure availability of those materials before the job is scheduled. Manu ally checking inventory when the preventive maintenance work order is created achieves this goal. The order should be held in a "waiting for resources" status until the parts, tools, procedures, and personnel are available. Parts will usually be the missing link in those logistics requirements. The parts required should be written on a pick list or a copy of the work order given to the stock keeper. He or she should pull those parts and consolidate them into a specified pickup area. It’s helpful if the stock keeper writes that bin number on the work order copy or pick list and returns it to the scheduler so that the scheduler knows a person can be assigned to the job and production can be contacted to make the equipment available, knowing that all other resources are ready. It may help to send two copies of the work order or pick list to the stock keeper so that one of them can be returned with the part confirmation and location. Then, when the craftsperson is given the work order assignment, he or she sees on the work order exactly where to go to find the parts ready for immediate use.

It can be helpful, when specific parts are often needed for preventive maintenance, to package them together in a kit. This standard selection of parts is much easier to pick, ship, and use, compared to gathering the individual items. Plugs, points, and a con denser are an example of an automobile tune-up kit, while air filters, drive belts, and disposable oilers are common with computer service representatives. Kits also make it easier to record the parts used for maintenance with less effort than the individual recording of piece parts. Any parts that are not used, either from kits or from individual draws, should be returned to the stockroom.

With a computer support system, parts availability can be automatically checked when the work order is dispatched. If the parts are not in the stockroom, the computer will indicate in a few seconds by a message on the screen that "All parts are not available; check the pick list." The pick list will show what parts are not on hand and what their status is, including availability with other personnel and quantities on order, at the receiving dock, or at the quality-control receiving inspection. The scheduler can then decide whether the parts could be obtained quickly from another source to schedule the job now, or perhaps to place the parts on order and hold the work request until the parts arrive. The parts should be identified with a work order so that receiving personnel know to expedite their inspection and shipment to the stockroom, or perhaps can be shipped directly to the requiring location.

A similar capability should be established for parts that are required to do major over hauls and unique planned jobs. Working with the equipment drawing and replaceable parts catalog, one should prepare a list of all parts that may possibly be required.

Failure-rate data and predictive information from condition monitoring should be reviewed to indicate any parts with a high probability of need. Parts replaced on previous, similar work should also be reviewed-both for those that obviously must be replaced at every teardown and for those that will definitely not be replaced because they were installed the last time.

Once the list of parts needs is established, internal inventory should be checked and available parts should be staged to an area in preparation for the planned work. Special orders should be placed for the additional required parts, just as they are placed to fill any other need.

Repairable Parts:

Repairable parts should receive the same kind of advance planning. If it can be afforded as a trade-off against reduced downtime, a good part should be available to install and the removed repairable parts should be rebuilt later and then restocked to inventory. If a replacement part cannot be made available, then at least all tools, fixtures, materials, and skilled personnel should be standing by when the repairable part is removed.

The condition of repairable parts, as well as those that are throwaways, should be evaluated as soon as convenient. The purpose is to measure the parameters that could lead to failure and to determine how much longer the part could be expected to operate without failure. If examination shows that considerable life is left on the part, then the preventive maintenance task or rebuild interval should be extended in the future.

Removed repairable parts should be tagged to indicate why they were removed.

Nothing is more frustrating to a repairperson then trying to find a defect that does not exist.

Detailed Procedures:

This topic has been covered earlier but should be reemphasized to ensure that the best balance is developed between details and general functions. The following are some general guidelines:

• Common words in short sentences should be used, with a reading comprehension level no higher than seventh grade.

• Illustrations should be used where possible, especially to point out critical measurements.

• Commonly done tasks should be referred to by function, whereas those tasks that are done once a year or less frequently may be described in detail.

• Daily and weekly checklists should be protected with a transparent cover and kept on equipment.

• Inspections and maintenance done once a month or less often should be issued as specific work orders.

• The craftsperson's signature should be required on every completed job.

• Management should complete a follow-up inspection on at least a large sample of the jobs in order to ensure quality.

• Failure rates on equipment should be tracked to increase inspection and preventive maintenance on items that are failing and to decrease efforts where there is little payoff.

• What was done and how much time it took should be recorded as guidance for future work.

Quality Assurance:

Quality of maintenance is a subject that requires more emphasis than it has received in the past. Like quality of any product, maintenance quality must be designed and built in. It cannot be inspected into the job.

The quality of inspection and preventive maintenance tasks starts with well-designed procedures, equipment, and a surrounding environment that is conducive to good maintenance and management emphasis. The procedures must then be followed properly, adequate time provided to the craftsperson to do the job well, and standards available with training to illustrate what is expected. There is one best way to do most inspections and preventive maintenance. That way should be detailed in a set of procedures and controlled to ensure successful completion.

First-line supervision is critical. Forepersons should spend most of their time managing their people at the work site and ensuring that customers are satisfied. It’s not possible to manage preventive maintenance from behind a desk. A foreperson must get out and participate in the jobs as they are being done and inspect them on completion. This motivates people to do both high-quantity and high-quality work. The foreperson will be on the site to apply corrective action as needed and to provide final job inspection and close out the work order.

Avoiding Callbacks:

"Callbacks" are generally defined as any repeat requirements for maintenance that may result from problems that should have been alleviated earlier or that were caused by earlier maintenance. Some organizations define a callback as any emergency maintenance on the same equipment within 24 hours for any reason. Other organizations narrow their definition to the same problem but within periods as long as 30 days. A measure should be chosen that suits the specific type of equipment. If your organization services for pay, you certainly should not charge additional for callback service because the problem should have been fixed the first time.

The fact remains that low-reliability people often service highly reliable equipment.

Preventive maintenance often incurs exposure to potential damage. The same steps that improve quality assurance also reduce the incidence of callbacks:

1. Establish and follow detailed procedures.

2. Train and motivate persons on the importance of thorough preventive maintenance.

3. If it works, don't fix it.

4. Conduct a complete operational test after maintenance is complete.

===

TBL. 3 Criteria for Preventive Maintenance Repair Method

Repair Separate from PM

Enables more accurate scheduling of B PM, at consistent times.

Allows use of inspection specialists with separate repair experts.

Allows parts, tools and documents to be obtained as required, instead of carrying extensive inventory.

Repair with PM

Best if:

Equipment is difficult to get from production.

Extensive tear down is involved that would have to be repeated for separate repairs.

Extensive travel time is required to return to the location.

It’s difficult for the person discovering the problem to describe it to another repair person.

===

Repairs at Preventive Maintenance:

Two philosophies exist on the best way to handle repairs that are detected during preventive maintenance. One approach is to fix everything as it’s discovered. The other extreme is to repair nothing but rather mark it on the work order and ensure that follow-up work orders are created. A policy that falls between the two is recommended: fix the minor things that can be most quickly done while the equipment is available, and identify other problems for separate work orders. A guideline limit of 10 minutes has proved useful to separate tasks that should be done at the time from those that should be scheduled separately. Naturally, any safety problem that is found should result in shutdown of the equipment and be repaired before the equipment is operated again. Restricting the amount of repair done on preventive maintenance work orders helps control these activities so they can stay on schedule. TBL. 3 outlines the criteria to be considered for repair with preventive versus separate repair.

It can thus be seen that a small workforce with multi-skilled persons servicing equipment that requires long travel, has delay time to get on the equipment, and requires extensive preparation and access time should make repairs at the same time as preventive tasks. If, however, the workforce is large enough to be specialized and supports large numbers of similar equipment that are located close together, then the inspection/preventive maintenance function should be separated from repairs. In general, most manufacturing plants should do repairs separately from preventive tasks.

Most field service personnel will do both at the same time.

Data Gathering:

Maintenance management needs data, but maintenance personnel don’t like to report data. Given this disparity between supply and demand, everything possible should be done to minimize data requirements, make data easy to obtain, and enforce accurate reporting. The main information needed from inspection and preventive activity is as follows:

- • That the job was done

- • Equipment used in meter reading

- • Part numbers of any parts replaced

- • Repair work requests to fix discovered problems

- • Time involved

As preventive maintenance sophistication increases toward predictive maintenance, the test measurements should be recorded so that signature and trend analysis with control limits can be used to guide future maintenance actions.

CONCLUSION

The following points summarize some of the main concepts in the preceding discussions:

• Preventive maintenance is necessary for most durable hardware.

• Preventive maintenance enables preaction, which is better than reaction.

• It’s necessary to plan.

• A good data collection and information analysis system must be established to guide efforts.

• All possible maintenance should be done at a single access.

• Safety must be regarded as paramount.

• Vital components must be inspected.

• Anything that is defective must be repaired.

• If it works, don't fix it.