Talk is cheap because supply exceeds demand.

Challenge--Quantities and Prices of Genetically Modified Foods

Countries around the globe are debating whether to permit firms to grow or sell genetically modified (GM) foods, which have their DNA altered through genetic engineering rather than through conventional breeding. [1] The introduction of GM techniques can affect both the quantity of a crop farmer's supply and whether consumers want to buy that crop.

The first commercial GM food was Calgene's Flavr Savr tomato, which the company claimed resisted rotting and could stay on the vine longer to ripen to full flavor.

It was first marketed in 1994 without any special labeling. Other common GM crops include canola, corn, cotton, rice, soybean, and sugar cane. Using GM techniques, farmers can produce more output at a given cost.

As of 2012, GM food crops, which are mostly insect-resistant, herbicide-tolerant, or stacked gene (has several traits) varieties of corn, soybean, and canola oilseed, were grown in 29 countries, but over 40% of the acreage was in the United States. In the United States in 2012, the share of crops that were GM was 88% for corn, 93% for soybean, and 94% for cotton.

Some scientists and consumer groups have raised safety concerns about GM crops.

In some countries, certain GM foods have been banned. In 2008, the European Union (EU) was forced to end its de facto ban on GM crop imports when the World Trade Organization ruled that the ban lacked scientific merit and hence violated international trade rules. As of 2013, most of the EU still banned planting most GM crops. In the EU, Australia, and several other countries, governments have required that GM products be labeled. Although Japan has not approved the cultivation of GM crops, it is the nation with the greatest GM food consumption and does not require labeling.

According to some polls, 70% of consumers in Europe object to GM foods. Fears cause some consumers to refuse to buy a GM crop (or the entire crop if GM products can not be distinguished). Consumers in other countries, such as the United States, are less concerned about GM foods.

Whether a country approves GM crops turns on questions of safety and of economics. Will the use of GM seeds lead to lower prices and more food sold? What happens to prices and quantities sold if many consumers refuse to buy GM crops? (We will return to these questions at the end of this section.)

========

In this section, we examine six main topics

1. Demand. The quantity of a good or service that consumers demand depends on price and other factors such as consumers' incomes and the price of related goods.

2. Supply. The quantity of a good or service that firms supply depends on price and other factors such as the cost of inputs firms use to produce the good or service.

3. Market Equilibrium. The interaction between consumers' demand and firms' supply deter mines the market price and quantity of a good or service that is bought and sold.

4. Shocking the Equilibrium. Changes in a factor that affect demand (such as consumers' incomes), supply (such as a rise in the price of inputs), or a new government policy (such as a new tax) alter the market price and quantity of a good.

5. Equilibrium Effects of Government Interventions. Government policies may alter the equilibrium and cause the quantity supplied to differ from the quantity demanded.

6. When to Use the Supply-and-Demand Model. The supply-and-demand model applies only to competitive markets.

========

1. Demand

Potential consumers decide how much of a good or service to buy on the basis of its price and many other factors, including their own tastes, information, prices of other goods, income, and government actions. Before concentrating on the role of price in determining demand, let's look briefly at some of the other factors.

Consumers' tastes determine what they buy. Consumers do not purchase foods they dislike, artwork they hate, or clothes they view as unfashionable or uncomfortable. Advertising may influence people's tastes.

To analyze questions concerning the price and quantity responses from introducing new products or technologies, imposing government regulations or taxes, or other events, economists may use the supply-and-demand model. When asked, "What is the most important thing you know about economics?" a common reply is, "Supply equals demand." This statement is a shorthand description of one of the simplest yet most powerful models of economics. The supply-and-demand model describes how consumers and suppliers interact to determine the quantity of a good or service sold in a market and the price at which it is sold. To use the model, you need to determine three things: buyers' behavior, sellers' behavior, and how they interact.

After reading this section, you should be adept enough at using the supply-and demand model to analyze some of the most important policy questions facing your country today, such as those concerning international trade, minimum wages, and price controls on health care.

After reading that grandiose claim, you may ask, "Is that all there is to economics? Can I become an expert economist that fast?" The answer to both these questions is no, of course. In addition, you need to learn the limits of this model and what other models to use when this one does not apply. (You must also learn the economists' secret handshake.)

Even with its limitations, the supply-and-demand model is the most widely used economic model. It provides a good description of how competitive markets function.

Competitive markets are those with many buyers and sellers, such as most agriculture markets, labor markets, and stock and commodity markets. Like all good theories, the supply-and-demand model can be tested-and possibly shown to be false. But in competitive markets, where it works well, it allows us to make accurate predictions easily.

Similarly, information (or misinformation) about the uses of a good affects consumers' decisions. A few years ago when many consumers were convinced that oat meal could lower their cholesterol level, they rushed to grocery stores and bought large quantities of oatmeal. (They even ate some of it until they remembered that they couldn't stand how it tastes.) The prices of other goods also affect consumers' purchase decisions. Before deciding to buy Levi's jeans, you might check the prices of other brands. If the price of a close substitute-a product that you view as similar or identical to the one you are considering purchasing-is much lower than the price of Levi's jeans, you may buy that brand instead. Similarly, the price of a complement-a good that you like to consume at the same time as the product you are considering buying-may affect your decision. If you eat pie only with ice cream, the higher the price of ice cream, the less likely you are to buy pie.

Income plays a major role in determining what and how much to purchase. People who suddenly inherit great wealth may purchase a Rolls-Royce or other luxury items and would probably no longer buy do-it-yourself repair kits.

Government rules and regulations affect purchase decisions. Sales taxes increase the price that a consumer must spend for a good, and government-imposed limits on the use of a good may affect demand. In the nineteenth century, one could buy Bayer heroin, a variety of products containing cocaine, and other drug-related products that are now banned in most countries. When a city's government bans the use of skate boards on its streets, skateboard sales fall. [2]

[2 when a Mississippi woman attempted to sell her granddaughter for $2,000 and a car, state legislators were horrified to discover that they had no law on the guides prohibiting the sale of children and quickly passed such a law. (Mac Gordon, "Legislators Make Child-Selling Illegal," Jackson Free Press, March 16, 2009.)]

Other factors may also affect the demand for specific goods. Consumers are more likely to use a particular smart phone app (application) if their friends use that one.

The demand for small, dead evergreen trees is substantially higher in December than in other months.

Although many factors influence demand, economists usually concentrate on how price affects the quantity demanded. The relationship between price and quantity demanded plays a critical role in determining the market price and quantity in a supply-and-demand analysis. To determine how a change in price affects the quantity demanded, economists must hold constant other factors such as income and tastes that affect demand.

quantity demanded---the amount of a good that consumers are willing to buy at a given price, holding constant the other factors that influence purchases

demand curve--the quantity demanded at each possible price, holding constant the other factors that influence purchases

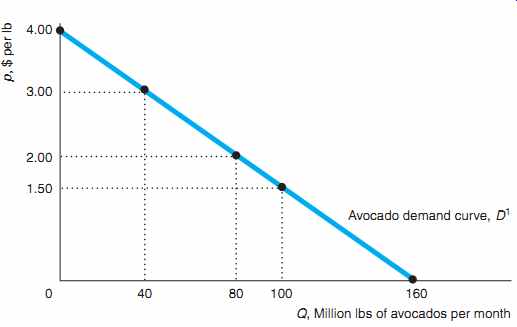

FIG. 1 A Demand Curve -- The estimated demand curve, D1 , for avocados

shows the relationship between the quantity demanded per month and the

price per lb. The downward slope of this demand curve shows that, holding

other factors that influence demand constant, consumers demand fewer

avocados when the price rises and more when the price falls. That is,

a change in price causes a movement along the demand curve.

The Demand Curve

The amount of a good that consumers are willing to buy at a given price, holding constant the other factors that influence purchases, is the quantity demanded. The quantity demanded of a good or service can exceed the quantity actually sold. For example, as a promotion, a local store might sell DVDs for $1 each today only. At that low price, you might want to buy 25 DVDs, but because the store ran out of stock, you can buy only 10 DVDs. The quantity you demand is 25-it's the amount you want, even though the amount you actually buy is only 10.

We can show the relationship between price and the quantity demanded graphically. A demand curve shows the quantity demanded at each possible price, holding constant the other factors that influence purchases. FIG. 1 shows the estimated monthly demand curve, D1 , for avocados in the United States.3 Although this demand curve is a straight line, demand curves may also be smooth curves or wavy lines. By convention, the vertical axis of the graph measures the price, p, per unit of the good.

Here the price of avocados is measured in dollars per pound (abbreviated "lb"). The horizontal axis measures the quantity, Q, of the good, which is usually expressed in some physical measure per time period. Here, the quantity of avocados is measured in millions of pounds (lbs) per month.

The demand curve hits the vertical axis at $4, indicating that no quantity is demanded when the price is $4 per lb or higher. The demand curve hits the horizontal quantity axis at 160 million lbs per month, the quantity of avocados that consumers would want if the price were zero. To find out what quantity is demanded at a price between zero and $4, we pick that price-say, $2-on the vertical axis, draw a horizontal line across until we hit the demand curve, and then draw a vertical line down to the horizontal quantity axis. As the figure shows, the quantity demanded at a price of $2 per lb is 80 million lbs per month.

One of the most important things to know about the graph of a demand curve is what is not shown. All relevant economic variables that are not explicitly included in the demand curve graph-income, prices of other goods (such as other fruits or vegetables), tastes, information, and so on-are held constant. Thus, the demand curve shows how quantity varies with price but not how quantity varies with income, the price of substitute goods, tastes, information, or other variables. [4]

3. To obtain our estimated supply and demand curves, we used estimates from Carman (2006), which we updated with more recent (2012) data from the California Avocado Commission and supplemented with information from other sources. The numbers have been rounded so that the figures use whole numbers.

4. Because prices, quantities, and other factors change simultaneously over time, economists use statistical techniques to hold the effects of factors other than the price of the good constant so that they can determine how price affects the quantity demanded. As with any estimate, the demand curve estimates are probably more accurate in the observed range of prices than at very high or very low prices.

Law of Demand--consumers demand more of a good the lower its price, holding constant tastes, the prices of other goods, and other factors that influence consumption

Effect of Prices on the Quantity Demanded

Many economists claim that the most important empirical finding in economics is the Law of Demand: Consumers demand more of a good the lower its price, holding constant tastes, the prices of other goods, and other factors that influence the amount they consume. According to the Law of Demand, demand curves slope downward, as in FIG. 1. 5

A downward-sloping demand curve illustrates that consumers demand a larger quantity of this good when its price is lowered and a smaller quantity when its price is raised. What happens to the quantity of avocados demanded if the price of avocados drops and all other variables remain constant? If the price of avocados falls from $2.00 per lb to $1.50 per lb in FIG. 1, the quantity consumers want to buy increases from 80 million lbs to 100 million lbs. 6 Similarly, if the price increases from $2 to $3, the quantity consumers demand decreases from 80 to 40.

These changes in the quantity demanded in response to changes in price are movements along the demand curve. Thus, the demand curve concisely summarizes the answers to the question "What happens to the quantity demanded as the price changes, when all other factors are held constant?"

Effects of Other Factors on Demand

If a demand curve measures the effects of price changes when all other factors that affect demand are held constant, how can we use demand curves to show the effects of a change in one of these other factors, such as the price of tomatoes? One solution is to draw the demand curve in a three dimensional diagram with the price of avocados on one axis, the price of tomatoes on a second axis, and the quantity of avocados on the third axis. But what would you do if the demand curve depended on one more factor? Economists use a simpler approach to show the effect on demand of a change in a factor that affects demand other than the price of the good. A change in any factor other than the price of the good itself causes a shift of the demand curve rather than a movement along the demand curve.

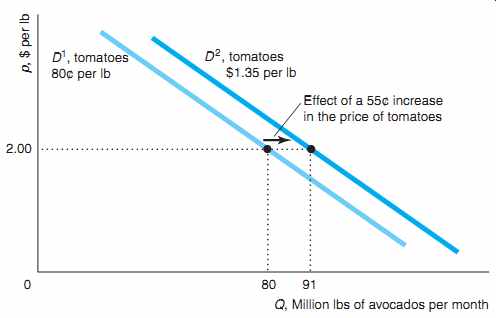

The price of substitute goods affects the quantity of avocados demanded. Many consumers view tomatoes as a substitute for avocados. The original, estimated avocado demand curve in FIG. 1 is based on an average price of tomatoes of $0.80 per lb. FIG. 2 shows how the avocado demand curve shifts outward or to the right from the original demand curve D1 to a new demand curve D2

if the price of tomatoes increases by 55¢. On D2 , more avocados are demanded at any given price than on D1 because tomatoes, a substitute good, have become more expensive.

At a price of $2 per lb, the quantity of avocados demanded goes from 80 million lbs on D1, before the increase in the price of tomatoes, to 91 million lbs on D2, after the increase.

Similarly, consumers tend to buy more avocados as their incomes rise. Thus, if income rises, the demand curve for avocados shifts to the right, indicating that consumers demand more avocados at any given price.

------------

5. Theoretically, a demand curve could slope upward (Section 5); however, available empirical evidence strongly supports the Law of Demand.

6. Economists typically do not state the relevant physical and time period measures unless they are particularly useful. They refer to quantity rather than something useful such as "metric tons per year" and price rather than "cents per pound." I'll generally follow this convention, usually refer ring to the price as $2 (with the "per lb" understood) and the quantity as 80 (with the "million lbs per month" understood).

------------

FIG. 2 A Shift of the Demand Curve--The demand curve for avocados

shifts to the right from D1 to D2 as the price of tomatoes, a substitute,

increases by 55¢ per lb. As a result of the increase in the price of

tomatoes, more avocados are demanded at any given price.

Other factors may also affect the demand curve for various goods. For example, if cigarettes become more addictive, the demand curve of existing smokers would shift to the right.

[7. Similarly, information can shift a demand curve. Reinstein and Snyder (2005) found that favorable movie reviews shifted the opening weekend demand curve to the right by 25% for a drama, but favorable reviews did not significantly shift the demand curve for an action film or a comedy. ]

To properly analyze the effects of a change in some variable on the quantity demanded, we must distinguish between a movement along a demand curve and a shift of a demand curve. A change in the price of a good causes a movement along a demand curve. A change in any other factor besides the price of the good causes a shift of the demand curve.

=====================

Application

Calorie Counting at Starbucks

New York City started requiring mandatory posting of calories on menus in chain restaurants in mid-2008. Bollinger, Leslie, and Sorensen (2011) found that New York City's mandatory calorie posting caused average calories per transaction at Starbucks to fall by 6% due to reduced consumption of high-calorie foods. They found larger responses to information among wealthier and better-educated consumers and among those who prior to the law consumed relatively more calories.

Some states have since passed similar laws. Although a 2010 U.S. health care law required that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) write rules requiring chain restaurants and other firms to post calories on menus and in vending machines, the FDA had not written the rules by June 2013. Nonetheless, some firms have started posting such information. McDonald's announced in 2012 that it would start posting calorie information on its menus, and Coca-Cola announced in 2013 that it would put calorie information on the front of its products.

==================

7. A Harvard School of Public Health study concluded that cigarette manufacturers raised nicotine levels in cigarettes by 11% from 1998 to 2005 to make them more addictive. Gardiner Harris, "Study Showing Boosted Nicotine Levels Spurs Calls for Controls," San Francisco Chronicle, January 19, 2007, A-4.

The Demand Function

The demand curve shows the relationship between the quantity demanded and a good's own price, holding other relevant factors constant at some particular levels.

Graphically, we illustrate the effect of a change in one of these other relevant factors by shifting the demand curve. We can represent the same information-information about how price, income, and other variables affect quantity demanded-using a demand function. The demand function shows the effect of all the relevant factors on the quantity demanded.

The quantity of avocados demanded varies with the price of avocados, the price of tomatoes, and income, so the avocado demand function, D, is Q = D(p, pt, Y) (eqn. 1)

where Q is the quantity of avocados demanded, p is the price of avocados, pt is the price of tomatoes, and Y is the income of consumers. Any other factors that are not explicitly listed in the demand function are assumed to be irrelevant (such as the price of llamas in Peru) or held constant (such as the prices of other related goods, tastes, and consumer information).

Equation 1 is a general functional form-it does not specify exactly how Q varies with the explanatory variables, p, pt, and Y. The estimated demand function that corresponds to the demand curve D1 in FIGs. 1 and 2 has a specific (linear) form. If we measure quantity in millions of lbs per month, avocado and tomato prices in dollars per lb, and average monthly income in dollars, the demand function is

Q = 104 - 40p + 20pt + 0.01Y. (eqn. 2)

When we draw the demand curve D1 in FIG. 1 and 2.2, we hold pt and Y at specific values. The price per lb for tomatoes is $0.80, and average income is $4,000 per month. If we substitute these values for pt and Y in Equation 2.2, we can rewrite the quantity demanded as a function of only the price of avocados:

Q = 104 - 40p + 20pt + 0.01Y

= 104 - 40p + (20 * 0.80) + (0.01 * 4,000)

= 160 - 40p. (eqn. 3)

The linear demand function in Equation 3 corresponds to the straight-line demand curve D1 in FIG. 1 with particular given values for the price of tomatoes and for income. The constant term, 160, in Equation 3 is the quantity demanded (in millions of lbs per month) if the price is zero. Setting the price equal to zero in Equation 3, we find that the quantity demanded is:

Q = 160 - (40 * 0) = 160. FIG. 1 shows that

Q = 160 where D1

hits the quantity axis-where price is zero.

We can use Equation 3 to determine how the quantity demanded varies with a change in price: a movement along the demand curve. If the price falls from p1 to p2, the change in price, Δp, equals p2 - p1. (The ? symbol, the Greek letter delta, means "change in" the variable following the delta, so ?p means "change in price.") If the price of avocados falls from p1 = $2 to p2 = $1.50, then ?p = $1.50 - $2 = -$0.50.

The quantity demanded changes from Q1 = 80 at a price of $2 to Q2 = 100 at a price of $1.50, so ?Q = Q2 - Q1 = 100 - 80 = 20 million lbs per month. That is, as price falls by 50¢ per pound, the quantity rises by 20 million lbs per month.

More generally, the quantity demanded at p1 is Q1 = D(p1), and the quantity demanded at p2 is Q2 = D(p2). The change in the quantity demanded, ?Q = Q2 - Q1, in response to the price change (using Equation 2.3) is

?Q = Q2 - Q1

= D(p2) - D(p1)

= (160 - 40p2) - (160 - 40p1)

= -40(p2 - p1)

= -40?p.

Thus, the change in the quantity demanded, ?Q, is -40 times the change in the price,

?p. For example, if ?p = -$0.50, then ?Q = -40?p = -40(-0.50) = 20 million lbs.

This effect is consistent with the Law of Demand. A 50¢ decrease in price causes a 20 million lb per month increase in quantity demanded. Similarly, raising the price would cause the quantity demanded to fall.

The slope of a demand curve is ?p/?Q, the "rise" (?p, the change along the vertical axis) divided by the "run" (?Q, the change along the horizontal axis). The slope of demand curve D1 in FIG. 1 and 2.2 is Slope = rise run

=

?p

?Q =

$1 per lb

-40 million lbs per month

= -$0.025 per million lbs per month.

The negative sign of this slope is consistent with the Law of Demand. The slope says that the price rises by $1 per lb as the quantity demanded falls by 40 million lbs per month.

Thus, we can use the demand curve to answer questions about how a change in price affects the quantity demanded and how a change in the quantity demanded affects price. We can also answer these questions using demand functions.

Summing Demand Curves

If we know the demand curve for each of two consumers, how do we determine the total demand curve for the two consumers combined? The total quantity demanded at a given price is the sum of the quantity each consumer demands at that price.

We can use the demand functions to determine the total demand of several consumers. Suppose that the demand function for Consumer 1 is

Q1 = D1 (p) and the demand function for Consumer 2 is Q2 = D2 (p).

At price p, Consumer 1 demands Q1 units, Consumer 2 demands Q2 units, and the total demand of both consumers is the sum of the quantities each demands separately:

Q = Q1 + Q2 = D1 (p) + D2 (p).

We can generalize this approach to look at the total demand for three or more consumers.

It makes sense to add the quantities demanded only when all consumers face the same price. Adding the quantity Consumer 1 demands at one price to the quantity Consumer 2 demands at another price would be like adding apples and oranges.

============

Application

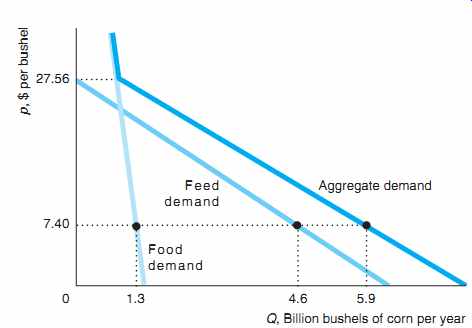

Aggregating Corn Demand Curves

We illustrate how to combine individual demand curves to get an aggregate demand curve graphically using estimated demand curves for corn. The figure shows the U.S. feed demand (the use of corn to feed animals) curve, the U.S. food demand curve, and the aggregate demand curve from these two sources.

[8] To derive the sum of the quantity demanded for these two uses at a given price, we add the quantities from the individual demand curves at that price. That is, we add the demand curves horizontally. At the 2012 average price for corn, $7.40, the quantity demanded for food is 1.3 billion bushels per year and the quantity demanded for feed is 4.6 billion bushels. Thus, the total quantity demanded at that price is

Q = 1.3 + 4.6 = 5.9.

When the price of corn exceeds $27.56 per bushel, farmers stop using corn for animal feed, so the quantity demanded for this use equals zero. Thus, the total demand curve is the same as the food demand curve at prices above $27.56.

-------p 17

============

2. Supply

Knowing how much consumers want is not enough by itself for us to determine the market price and quantity. We also need to know how much firms want to supply at any given price.

Firms determine how much of a good to supply based on the price of that good and other factors, including the costs of production and government rules and regulations. Usually, we expect firms to supply more at a higher price. Before concentrating on the role of price in determining supply, we'll briefly describe the role of some of the other factors.

Costs of production affect how much firms want to sell of a good. As a firm's cost falls, it is willing to supply more, all else the same. If the firm's cost exceeds what it can earn from selling the good, the firm sells nothing. Thus, factors that affect costs also affect supply. A technological advance that allows a firm to produce a good at lower cost leads the firm to supply more of that good, all else the same.

Government rules and regulations affect how much firms want to sell or are allowed to sell. Taxes and many government regulations--such as those covering pollution, sanitation, and health insurance--alter the costs of production. Other regulations affect when and how the product can be sold. In some countries, retailers may not sell most goods and services on days of particular religious significance.

In the United States, the sale of cigarettes and liquor to children is prohibited. Many cities around the world restrict the number of taxicabs.

quantity supplied-- the amount of a good that firms want to sell at a given price, holding constant other factors that influence firms' supply decisions, such as costs and government actions

supply curve--- the quantity supplied at each possible price, holding constant the other factors that influence firms' supply decisions

The Supply Curve

The quantity supplied is the amount of a good that firms want to sell at a given price, holding constant other factors that influence firms' supply decisions, such as costs and government actions. We can show the relationship between price and the quantity supplied graphically. A supply curve shows the quantity supplied at each possible price, holding constant the other factors that influence firms' supply decisions.

FIG. 3 shows the estimated supply curve, S1 , for avocados. As with the demand curve, the price on the vertical axis is measured in dollars per physical unit (dollars per lb), and the quantity on the horizontal axis is measured in physical units per time period (millions of lbs per month). Because we hold fixed other variables that may affect the supply, such as costs and government rules, the supply curve concisely answers the question "What happens to the quantity supplied as the price changes, holding all other factors constant?"

Effects of Price on Supply

We illustrate how price affects the quantity supplied using the supply curve for avocados in FIG. 3. The supply curve is upward sloping. As the price increases, firms supply more. If the price is $2 per lb, the quantity supplied by the market is 80 million lbs per month. If the price rises to $3, the quantity supplied rises to 95 million lbs. An increase in the price of avocados causes a movement along the supply curve, so more avocados are supplied.

Although the Law of Demand requires that the demand curve slope downward, we have no "Law of Supply" that requires the market supply curve to have a particular slope. The market supply curve can be upward sloping, vertical, horizontal, or down ward sloping. Many supply curves slope upward, such as the one for avocados. Along such supply curves, the higher the price, the more firms are willing to sell, holding costs and government regulations fixed.

Effects of Other Variables on Supply

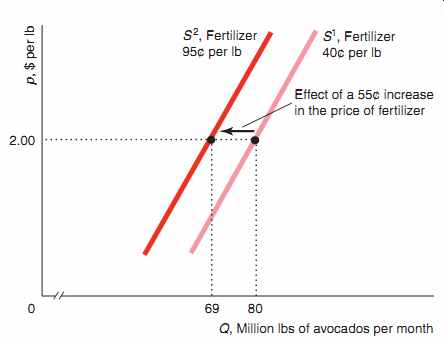

A change in a relevant variable other than the good's own price causes the entire supply curve to shift. Suppose the price of fertilizer used to produce avocados increases by 55¢ from 40¢ to 95¢ per lb. This increase in the price of a key factor of production causes the cost of avocado production to rise. Because it is now more expensive to produce avocados, the supply curve shifts inward or to the left, from S1 to S2 in FIG. 4. [9] That is, firms want to supply fewer avocados at any given price than before the fertilizer-based cost increase. At a price of $2 per lb for avocados, the quantity supplied falls from 80 million lbs on S1 to 69 million on S2 (after the cost increase).

[9. Alternatively, we may say that the supply curve shifts up because firms' costs of production have increased, so that firms will supply a given quantity only at a higher price.]

FIG. 3 A Supply Curve --- The estimated supply curve, S1 , for avocados

shows the relation ship between the quantity sup plied per month and

the price per lb, holding constant cost and other factors that influence

supply. The upward slope of this supply curve indicates that firms supply

more of this good when its price is high and less when the price is low.

An increase in the price of avocados causes firms to supply a larger

quantity of avocados; any change in price results in a movement along

the supply curve.

Again, it is important to distinguish between a movement along a supply curve and a shift of the supply curve. When the price of avocados changes, the change in the quantity supplied reflects a movement along the supply curve. When costs, government rules, or other variables that affect supply change, the entire supply curve shifts.

FIG. 4 A Shift of a Supply Curve---A 55¢ per lb increase in the

price of fertilizer, which is used to produce avocados, causes the supply

curve for avocados to shift left from S1 to S2. At the price of avocados

at $2 per lb, the quantity supplied falls from 80 on S1 to 69 on S2.

The Supply Function

We can write the relationship between the quantity supplied and price and other factors as a mathematical relationship called the supply function. Using a general functional form, we can write the avocado supply function, S, as Q = S(p, pf), (eqn. 5)

where Q is the quantity of avocados supplied, p is the price of avocados, and pf is the price of fertilizer. The supply function, Equation 2.5, might also incorporate other factors such as wages, transportation costs, and the state of technology, but by leaving them out, we are implicitly holding them constant.

Our estimated supply function for avocados is Q = 58 + 15p - 20pf , (eqn 6)

where Q is the quantity in millions of lbs per month, p is the price of avocados in dollars per lb, and pf is the price of fertilizer in dollars per lb. If we fix the fertilizer price at 40¢ per lb, we can rewrite the supply function in Equation 2.6 as solely a function of the avocado price. Substituting pf = $0.40 into Equation 2.5, we find that Q = 58 + 15p - (20 * 0.40) = 50 + 15p. (2.7)

What happens to the quantity supplied if the price of avocados increases by

?p = p2 - p1? As the price increases from p1 to p2, the quantity supplied goes from Q1 to Q2, so the change in quantity supplied is

?Q = Q2 - Q1 = (50 + 15p2) - (50 + 15p1) = 15(p2 - p1) = 15?p.

Thus, a $1 increase in price (?p = 1) causes the quantity supplied to increase by

?Q = 15 million lbs per month. This change in the quantity of avocados supplied as p increases is a movement along the supply curve.

Summing Supply Curves

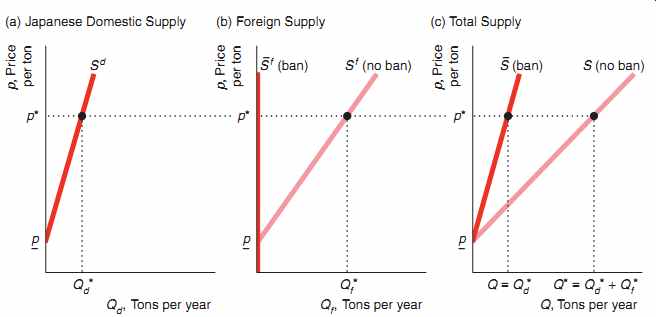

The total supply curve shows the total quantity produced by all suppliers at each possible price. For example, the total supply of rice in Japan is the sum of the domestic and foreign supply curves of rice.

Suppose that the domestic supply curve (panel a) and foreign supply curve (panel b) of rice in Japan are as FIG. 5 shows. The total supply curve, S in panel c, is the horizontal sum of the Japanese domestic supply curve, Sd , and the foreign supply curve, Sf.

In the figure, the Japanese and foreign supplies are zero at any price equal to or less than p, so the total supply is zero. At prices above p, the Japanese and foreign supplies are positive, so the total supply is positive. For example, when price is p*, the quantity supplied by Japanese firms is Q* d (panel a), the quantity supplied by foreign firms is Q* f (panel b), and the total quantity supplied is Q* = Q* d + Q* f (panel c).

Because the total supply curve is the horizontal sum of the domestic and foreign supply curves, the total supply curve is flatter than the other two supply curves.

Effects of Government Import Policies on Supply Curves

We can use this approach for deriving the total supply curve to analyze the effect of government policies on the total supply curve. Japan banned the importation of foreign rice until 1994 and even today severely restricts imports. We want to determine how much less was supplied at any given price to the Japanese market because of this ban.

Without a ban, the foreign supply curve is Sf in panel b of FIG. 5. A ban on imports eliminates the foreign supply, so the foreign supply curve after the ban is imposed, Sf , is a vertical line at Qf = 0. The import ban had no effect on the domestic supply curve, Sd , so the supply curve remains the same as in panel a.

Because the foreign supply with a ban, Sf , is zero at every price, the total supply with a ban, S, in panel c is the same as the Japanese domestic supply, Sd , at any given price. The total supply curve under the ban lies to the left of the total supply curve without a ban, S. Thus, the effect of the import ban is to rotate the total supply curve toward the vertical axis.

==========

FIG. 5 Total Supply: The Sum of Domestic and Foreign Supply

(a) Japanese Domestic Supply (b) Foreign Supply (c) Total Supply If foreigners may sell their rice in Japan, the total Japanese supply of rice, S, is the horizontal sum of the domestic Japanese supply, Sd , and the imported foreign supply, Sf.

With a ban on foreign imports, the foreign supply curve, Sf , is zero at every price, so the total supply curve, S, is the same as the domestic supply curve, Sd.

===========

3. Market Equilibrium

The supply and demand curves determine the price and quantity at which goods and services are bought and sold. The demand curve shows the quantities consumers want to buy at various prices, and the supply curve shows the quantities firms want to sell at various prices. Unless the price is set so that consumers want to buy exactly the same amount that suppliers want to sell, either some buyers cannot buy as much as they want or some sellers cannot sell as much as they want.

When all traders are able to buy or sell as much as they want, we say that the market is in equilibrium: a situation in which no one wants to change his or her behavior. A price at which consumers can buy as much as they want and sellers can sell as much as they want is called an equilibrium price. The quantity that is bought and sold at the equilibrium price is called the equilibrium quantity.

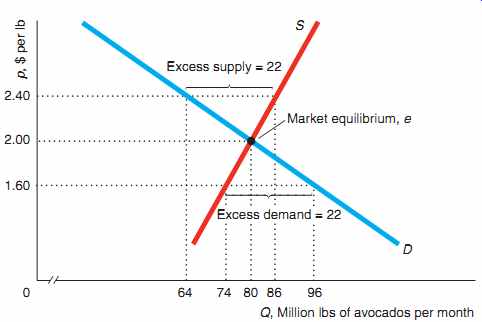

Using a Graph to Determine the Equilibrium

To illustrate how supply and demand curves determine the equilibrium price and quantity, we use our old friend, the avocado example. FIG. 6 shows the supply, S, and demand, D, curves for avocados. The supply and demand curves intersect at point e, the market equilibrium. The equilibrium price is $2 per lb, and the equilibrium quantity is 80 million lbs per month, which is the quantity firms want to sell at that price and the quantity consumers want to buy at that price.

Using Math to Determine the Equilibrium

We can determine the equilibrium mathematically, using algebraic representations of the supply and demand curves. We use these two equations to solve for the equilibrium price at which the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied (the equilibrium quantity). The demand curve, Equation 2.3, shows the relationship between the quantity demanded, Qd, and the price: 10

Qd = 160 - 40p.

The supply curve, Equation 7, tells us the relationship between the quantity supplied, Qs, and the price:

Qs = 50 + 15p.

We want to find the equilibrium price, p, at which Qd = Qs = Q, the equilibrium quantity. Thus, we set the right sides of these two equations equal,

50 + 15p = 160 - 40p,

and solve for the price. Adding 40p to both sides of this expression and subtracting 50 from both sides, we find that 55p = 110. Dividing both sides of this last expression by 55, we learn that the equilibrium price is p = 2.

We can determine the equilibrium quantity by substituting this p into either the supply equation or the demand equation. Using the demand equation, we find that the equilibrium quantity is

Q = 160 - (40 * 2) = 80 equilibrium a situation in which no one wants to change his or her behavior

million lbs per month. We obtain the same quantity by using the supply curve equation: Q = 50 + (15 * 2) = 80.

10 Usually, we use Q to represent both the quantity demanded and the quantity supplied. However, for clarity in this discussion, we use Qd and Qs.

FIG. 6 Market Equilibrium---The intersection of the supply curve,

S, and the demand curve, D, for avocados determines the market equilibrium

point, e, where p = $2 per lb and Q = 80 million lbs per month. At the

lower price of p = $1.60, the quantity supplied, 74, is less than the

quantity demanded, 96, which results in excess demand of 22. At p = $2.40,

a price higher than the equilibrium price, the excess supply is 22 because

the quantity demanded, 64, is less than the quantity supplied, 86. With

either excess demand or excess supply, market forces drive the price

back to the equilibrium price of $2.

Forces That Drive the Market to Equilibrium

A market equilibrium is not just an abstract concept or a theoretical possibility. We can observe markets in equilibrium. Indirect evidence that a market is in equilibrium is that you can buy as much as you want of the good at the market price. You can almost always buy as much as you want of such common goods as milk and ballpoint pens.

Amazingly, a market equilibrium occurs without any explicit coordination between consumers and firms. In a competitive market such as that for agricultural goods, millions of consumers and thousands of firms make their buying and selling decisions independently. Yet each firm can sell as much as it wants; each consumer can buy as much as he or she wants. It is as though an unseen market force, like an invisible hand, directs people to coordinate their activities to achieve a market equilibrium.

What really causes the market to move to an equilibrium? If the price is not at the equilibrium level, consumers or firms have an incentive to change their behavior in a way that will drive the price to the equilibrium level, as we now illustrate.

If the price were initially lower than the equilibrium price, consumers would want to buy more than suppliers want to sell. If the price of avocados is $1.60 in FIG. 5, firms are willing to supply 74 million lbs per month but consumers demand 96 million lbs. At this price, the market is in disequilibrium: the quantity demanded is not equal to the quantity supplied. The market has excess demand: the amount by which the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied at a specified price. At a price of $1.60 per lb, the excess demand is 22 (= 96 - 74) million lbs per month.

excess demand---the amount by which the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied at a specified price.

Some consumers are lucky enough to buy the avocados at $1.60 per lb. Other consumers cannot find anyone who is willing to sell them avocados at that price. What can they do? Some frustrated consumers may offer to pay suppliers more than $1.60 per lb. Alternatively, suppliers, noticing these disappointed consumers, might raise their prices. Such actions by consumers and producers cause the market price to rise.

As the price rises, the quantity that firms want to supply increases and the quantity that consumers want to buy decreases. This upward pressure on price continues until it reaches the equilibrium price, $2, where the excess demand is eliminated.

If, instead, the price is initially above the equilibrium level, suppliers want to sell more than consumers want to buy. For example, at a price of $2.40, suppliers want to sell 86 million lbs per month but consumers want to buy only 64 million lbs, as FIG. 5 shows. The market has an excess supply-the amount by which the quantity supplied is greater than the quantity demanded at a specified price-of 22(= 86 - 64) million lbs at a price of $2.40. Not all firms can sell as much as they want. Rather than allow their unsold avocados to spoil, firms lower the price to attract additional customers. As long as the price remains above the equilibrium price, some firms have unsold avocados and want to lower the price further. The price falls until it reaches the equilibrium level, $2, which eliminates the excess supply and hence removes the pressure to lower the price further. [11]

[11. Not all markets reach equilibrium through the independent actions of many buyers or sellers. In institutionalized or formal markets, such as the Chicago Mercantile Exchange-where agricultural commodities, financial instruments, energy, and metals are traded-buyers and sellers meet at a single location (or on a single Web site). In these markets, certain individuals or firms, sometimes referred to as market makers, act to adjust the price and bring the market into equilibrium very quickly.]

In summary, at any price other than the equilibrium price, either consumers or suppliers are unable to trade as much as they want. These disappointed people act to change the price, driving the price to the equilibrium level. The equilibrium price is called the market clearing price because it removes from the market all frustrated buyers and sellers: The market has no excess demand or excess supply at the equilibrium price.

excess supply---the amount by which the quantity supplied is greater than the quantity demanded at a specified price

top of page Similar Articles Home