4. Shocking the Equilibrium

Once an equilibrium is achieved, it can persist indefinitely because no one applies pressure to change the price. The equilibrium changes only if a shock occurs that shifts the demand curve or the supply curve. These curves shift if one of the variables we were holding constant changes. If tastes, income, government policies, or costs of production change, the demand curve or the supply curve or both shift, and the equilibrium changes.

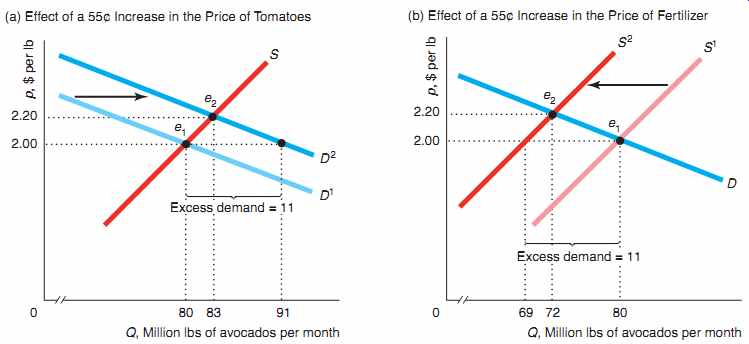

FIG. 7 Equilibrium Effects of a Shift of a Demand or Supply Curve

(a) Effect of a 55¢ Increase in the Price of Tomatoes (b) Effect of a

55¢ Increase in the Price of Fertilizer (a) A 55¢ per lb increase in

the price of tomatoes causes the demand curve for avocados to shift outward

from D1 to D2 . At the original equilibrium (e1) price of $2, excess

demand is 11 million lbs per month. Market pressures drive the price

up until it reaches $2.20 at the new equilibrium, e2. (b) An increase

in the price of fertilizer by 55¢ per lb causes producers' costs to rise,

so they supply fewer avocados at every price. The supply curve for avocados

shifts to the left from S1 to S2 , driving the market equilibrium from

e1 to e2, where the new equilibrium price is $2.20.

Effects of a Shift in the Demand Curve

Suppose that the price of fresh tomatoes increases by 55¢ per lb, so consumers substitute avocados for tomatoes. As a result, the demand curve for avocados shifts outward from D1 to D2 in panel a of FIG. 7. At any given price, consumers want more avocados than they did before the price of tomatoes rose. In particular, at the original equilibrium price of avocados of $2, consumers now want to buy 91 million lbs of avocados per month. At that price, however, suppliers still want to sell only 80 million lbs. As a result, excess demand is 11 million lbs. Market pressures drive the price up until it reaches a new equilibrium at $2.20. At that price, firms want to sell 83 million lbs and consumers want to buy 83 million lbs, the new equilibrium quantity. Thus, the equilibrium moves from e1 to e2 as a result of the increase in the price of tomatoes. Both the equilibrium price and the equilibrium quantity of avocados rise as a result of the outward shift of the avocado demand curve. Here the increase in the price of tomatoes causes a shift of the demand curve, which in turn causes a movement along the supply curve.

Effects of a Shift in the Supply Curve

Now suppose that the price of tomatoes stays constant at its original level but the price of fertilizer rises by 55¢ per lb. It is now more expensive to produce avocados because the price of an important input, fertilizer, has increased. As a result, the supply curve for avocados shifts to the left from S1 to S2 in panel b of FIG. 7. At any given price, producers want to supply fewer avocados than they did before the price of fertilizer increased. At the original equilibrium price for avocados of $2 per lb, consumers still want 80 million lbs, but producers are now willing to supply only 69 million lbs, so excess demand is 11 million lbs. Market pressure forces the price of avocados up until it reaches a new equilibrium at e2, where the equilibrium price is $2.20 and the equilibrium quantity is 72. The increase in the price of fertilizer causes the equilibrium price to rise but the equilibrium quantity to fall. Here a shift of the supply curve results in a movement along the demand curve.

In summary, a change in an underlying factor, such as the price of a substitute or the price of an input, shifts the demand curve or the supply curve. As a result of a shift in the demand or supply curve, the equilibrium changes. To describe the effect of this change, we compare the original equilibrium price and quantity to the new equilibrium values.

5. Equilibrium Effects of Government Interventions

A government can affect a market equilibrium in many ways. Sometimes government actions cause a shift in the supply curve, the demand curve, or both curves, which causes the equilibrium to change. Some government interventions, however, cause the quantity demanded to differ from the quantity supplied.

Policies That Shift Supply Curves

Governments employ a variety of policies that shift supply curves. Two common policies are licensing laws and quotas.

Licensing Laws A government licensing law limits the number of firms that may sell goods in a market. For example, many local governments around the world limit the number of taxicabs (see Section 9). Governments use zoning laws to limit the number of bars, bookstores, hotel chains, as well as firms in many other markets. In developed countries, licenses are distributed to early entrants or exams are used to determine who is licensed. In developing countries, licenses often go to relatives of government officials or to whomever offers those officials the largest bribe.

=========

Application

Occupational Licensing

Many occupations are licensed in the United States. In those occupations, working without a license is illegal. More than 800 occupations are licensed at the local, state, or federal level, including animal trainers, dietitians and nutritionists, doctors, electricians, embalmers, funeral directors, hair dressers, librarians, nurses, psychologists, real estate brokers, respiratory therapists, salespeople, teachers, and tree trimmers (but not economists).

During the early 1950s, fewer than 5% of U.S. workers were in occupations covered by licensing laws at the state level. Since then, the share of licensed workers has grown, reaching nearly 18% by the 1980s, at least 20% in 2000, and 29% in 2008. Licensing is more common in occupations that require extensive education: More than 40% of workers with post-college education are required to have a license compared to only 15% of those with less than a high school education.

In some occupations to get licensed one must pass a test, which is frequently designed by licensed members of the occupation. By making the exam difficult, cur rent workers can limit entry. For example, only 42% of people taking the California State Bar Examination in 2011 and 2012 passed it, although all of them had law degrees. (The national rate for lawyers passing state bar exams in 2012 was higher, but still only 67%.)

To the degree that testing is objective, licensing may raise the average quality of the workforce. However, its primary effect is to restrict the number of workers in an occupation. To analyze the effects of licensing, one can use a graph similar to panel b of FIG. 7, where the wage is on the vertical axis and the number of workers per year is on the horizontal axis. Licensing shifts the occupational sup ply curve to the left, reducing the equilibrium quantity of workers and raising the wage. Kleiner and Krueger (2013) found that licensing raises occupational wages by 18%.

==========

Quotas

Quotas typically limit the amount of a good that can be sold (rather than the number of firms that sell it). Quotas are commonly used to limit imports. As we saw earlier, quotas on imports affect the supply curve. We illustrate the effect of quotas on market equilibrium.

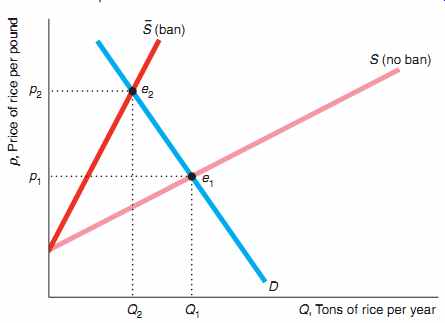

The Japanese government's ban (the quota was set to zero) on rice imports raised the price of rice in Japan substantially. FIG. 8 shows the Japanese demand curve for rice, D, and the total supply curve without a ban, S. The intersection of S and D determines the equilibrium, e1, if rice imports are allowed.

FIG. 8 A Ban on Rice Imports Raises the Price in Japan ---- A ban

on rice imports shifts the total supply of rice in Japan without a ban,

S, to S, which equals the domestic supply alone. As a result, the equilibrium

changes from e1 to e2. The ban causes the price to rise from p1 to p2

and the equilibrium quantity to fall to Q1 from Q2.

What is the effect of a ban on foreign rice on Japanese supply and demand? The ban has no effect on demand if Japanese consumers do not care whether they eat domestic or foreign rice. The ban causes the total supply curve to rotate toward the origin from S (total supply is the horizontal sum of domestic and foreign supply) to S (total supply equals the domestic supply).

The intersection of S and D determines the new equilibrium, e2, which lies above and to the left of e1. The ban caused a shift of the supply curve and a movement along the demand curve. It led to a fall in the equilibrium quantity from Q1 to Q2 and a rise in the equilibrium price from p1 to p2. Because of the Japanese nearly total ban on imported rice, the price of rice in Japan was 10.5 times higher than the price in the rest of the world in 2001, but is only about 50% higher today.

A quota of Q may have a similar effect to an outright ban; however, a quota may have no effect on the equilibrium if the quota is set so high that it does not limit imports. We investigate this possibility in Solved Problem 2.4.

Policies That Cause Demand to Differ from Supply

Some government policies do more than merely shift the supply or demand curve. For example, governments may control prices directly, a policy that leads to either excess supply or excess demand if the price the government sets differs from the equilibrium price. We illustrate this result with two types of price control programs: price ceilings and price floors. When the government sets a price ceiling at p, the price at which goods are sold may be no higher than p. When the government sets a price floor at p, the price at which goods are sold may not fall below p.

Price Ceilings

Price ceilings have no effect if they are set above the equilibrium price that would be observed in the absence of the price controls. If the government says that firms may charge no more than p = $5 per gallon of gas and firms are actually charging p = $1, the government's price control policy is irrelevant.

However, if the equilibrium price, p, was above the price ceiling p, the price actually observed in the market would be the price ceiling.

The United States used price controls during both world wars, the Korean War, and in 1971-1973 during the Nixon administration, among other times. The U.S. experience with gasoline illustrates the effects of price controls. In the 1970s, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) reduced supplies of oil (which is converted into gasoline) to Western countries. As a result, the total supply curve for gasoline in the United States- the horizontal sum of domestic and OPEC supply curves-shifted to the left from S1 to S2 in FIG. 9. Because of this shift, the equilibrium price of gasoline would have risen substantially, from p1 to p2. In an attempt to protect consumers by keeping gasoline prices from rising, the U.S. government set price ceilings on gasoline in 1973 and 1979.

The government told gas stations that they could charge no more than p = p1.

FIG. 9 shows the price ceiling as a solid horizontal line extending from the price axis at p. The price control is binding because p2 7 p. The observed price is the price ceiling. At p, consumers want to buy Qd = Q1 gallons of gasoline, which is the equilibrium quantity they bought before OPEC acted. However, firms supply only Qs gallons, which is determined by the intersection of the price control line with S2.

shortage---a persistent excess demand

As a result of the binding price control, excess demand is Qd - Qs.

Were it not for the price controls, market forces would drive up the market price to p2, where the excess demand would be eliminated. The government price ceiling prevents this adjustment from occurring. As a result, an enforced price ceiling causes a shortage: a persistent excess demand.

FIG. 9 Price Ceiling on Gasoline----After a shock, the supply curve

shifts from S1 to S2. Under the government's price control program, gasoline

stations may not charge a price above the price ceiling, p = p1. At that price,

producers are willing to supply only Qs, which is less than the amount

Q1 = Qd that consumers want to buy. The result is excessive demand, or

a shortage of Qd - Qs.

At the time of the controls, some government officials argued that the shortages were caused by OPEC's cutting off its supply of oil to the United States, but that's not true. Without the price controls, the new equilibrium would be e2. In this equilibrium, the price, p2, is much higher than before, p1; however, no shortage results.

Moreover, without controls, the quantity sold, Q2, is greater than the quantity sold under the control program, Qs.

With a binding price ceiling, the supply-and-demand model predicts an equilibrium with a shortage. In this equilibrium, the quantity demanded does not equal the quantity supplied. The reason that we call this situation an equilibrium, even though a shortage exists, is that no consumers or firms want to act differently, given the law.

Without the price controls, consumers facing a shortage would try to get more output by offering to pay more, or firms would raise prices. With effective government price controls, they know that they can't drive up the price, so they live with the shortage.

What happens? Some lucky consumers get to buy Qs units at the low price of p.

Other potential customers are disappointed: They would like to buy at that price, but they cannot find anyone willing to sell gas to them.

What determines which consumers are lucky enough to find goods to buy at the low price when a price control is imposed? With enforced price controls, sellers use criteria other than price to allocate the scarce commodity. Firms may supply their friends, long-term customers, or people of a certain race, gender, age, or religion.

They may sell their goods on a first-come, first-served basis. Or they may limit every one to only a few gallons.

Another possibility is for firms and customers to evade the price controls. A consumer could go to a gas station owner and say, "Let's not tell anyone, but I'll pay you twice the price the government sets if you'll sell me as much gas as I want." If enough customers and gas station owners behaved that way, no shortage would occur. A study of 92 major U.S. cities during the 1973 gasoline price controls found no gasoline lines in 52 of them. However, in cities such as Chicago, Hartford, New York, Portland, and Tucson, potential customers waited in line at the pump for an hour or more.

[13. Deacon and Sonstelie (1989) calculated that for every dollar consumers saved during the 1980 gasoline price controls, they lost $1.16 in waiting time and other factors. ]

This experience dissuaded most U.S. jurisdictions from imposing gasoline price controls, even when gasoline prices spiked following Hurricane Katrina in the summer of 2008. The one exception was Hawaii, which imposed price controls on the wholesale price of gasoline starting in September 2005, but suspended the controls indefinitely in early 2006 due to the public's unhappiness with the law. However, many other countries have imposed price controls on gasoline more recently, such as Argentina in 2013.

========

Application

Price Controls Kill

Robert G. Mugabe, who has ruled Zimbabwe with an iron fist for a third of a century, has used price controls to try to stay in power by currying favor among the poor.

[14. In 2001, he imposed price controls on many basic commodities, including food, soap, and cement, which led to shortages of these goods, and a thriving black, or parallel, market developed in which the controls were ignored. Prices on the black market were two or three times higher than the controlled prices. ]

He imposed more extreme controls in 2007. A government edict cut the prices of 26 essential items by up to 70%, and a subsequent edict imposed price controls on a much wider range of goods. Gangs of price inspectors patrolled shops and factories, imposing arbitrary price reductions. State-run newspapers exhorted citizens to turn in store owners whose prices exceeded the limits.

The Zimbabwean police reported that they arrested at least 4,000 businesspeople for not complying with the price controls. The government took over the nation's slaughterhouses after meat disappeared from stores, but in a typical week, butchers killed and dressed only 32 cows for the entire city of Bulawayo, which consists of 676,000 people.

Citizens initially greeted the price cuts with euphoria because they had been unable to buy even basic necessities because of hyperinflation and past price controls. Yet most ordinary citizens were unable to obtain much food because most of the cut rate merchandise was snapped up by the police, soldiers, and members of Mr. Mugabe's governing party, who were tipped off prior to the price inspectors' rounds.

Manufacturing slowed to a crawl because firms could not buy raw materials and because the prices firms received were less than their costs of production. Businesses laid off workers or reduced their hours, impoverishing the 15% or 20% of adult Zimbabweans who still had jobs. The 2007 price controls on manufacturing crippled this sector, forcing manufacturers to sell goods at roughly half of what it cost to produce them. By mid-2008, the output by Zimbabwe's manufacturing sector had fallen 27% compared to the previous year. As a consequence, Zimbabweans died from starvation.

Although we have no exact figures, according to the World Food Program, over five million Zimbabweans faced starvation in 2008.

Aid shipped into the country from international relief agencies and the two million Zimbabweans who had fled abroad helped keep some people alive. In 2008, the World Food Program made an urgent appeal for $140 million in donations to feed Zimbabweans, stating that drought and political upheaval would soon exhaust the organization's stockpiles. The economy shrank by 40% percent between 2000 and 2007. Thankfully, the price controls were lifted in 2009.

===========

Price Floors

Governments also commonly use price floors. One of the most important examples of a price floor is a minimum wage in a labor market. A minimum wage law forbids employers from paying less than the minimum wage, w.

Minimum wage laws date from 1894 in New Zealand, 1909 in the United Kingdom, and 1912 in Massachusetts. The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 set a federal U.S. minimum wage of 25¢ per hour. The U.S. federal minimum hourly wage rose to $7.25 in 2009 and remained at that level through mid-2013, but 19 states have higher state minimum wages. The minimum wage in Canada differs across provinces, ranging from C$9.50 to C$11.00 (where C$ stands for Canadian dollars, which roughly equal U.S. dollars) in 2013. The U.K. minimum wage for adults is £6.31 ($9.81) as of October 2013. If the minimum wage is binding-that is, if it exceeds the equilibrium wage, w*-it creates unemployment: a persistent excess supply of labor.

[15. The original 1938 U.S. minimum wage law caused massive unemployment in Puerto Rico.]

Why Supply Need Not Equal Demand

The price ceiling and price floor examples show that the quantity supplied does not necessarily equal the quantity demanded in a supply-and-demand model. The quantity supplied need not equal the quantity demanded because of the way we defined these two concepts. We defined the quantity supplied as the amount firms want to sell at a given price, holding other factors that affect supply, such as the price of inputs, constant. The quantity demanded is the quantity that consumers want to buy at a given price, if other factors that affect demand are held constant. The quantity that firms want to sell and the quantity that consumers want to buy at a given price need not equal the actual quantity that is bought and sold.

When the government imposes a binding price ceiling of p on gasoline, the quantity demanded is greater than the quantity supplied. Despite the lack of equality between the quantity supplied and the quantity demanded, the supply-and-demand model is useful in analyzing this market because it predicts the excess demand that is actually observed.

We could have defined the quantity supplied and the quantity demanded so that they must be equal. If we were to define the quantity supplied as the amount firms actually sell at a given price and the quantity demanded as the amount consumers actually buy, supply must equal demand in all markets because the quantity demanded and the quantity supplied are defined to be the same quantity.

It is worth pointing out this distinction because many people, including politicians and newspaper reporters, are confused on this point. Someone insisting that "demand must equal supply" must be defining supply and demand as the actual quantities sold.

Because we define the quantities supplied and demanded in terms of people's wants and not actual quantities bought and sold, the statement that "supply equals demand" is a theory, not merely a definition. This theory says that the equilibrium price and quantity in a market are determined by the intersection of the supply curve and the demand curve if the government does not intervene. Further, we use the model to predict excess demand or excess supply when a government does control price. The observed gasoline shortages during periods when the U.S. government controlled gasoline prices are consistent with this prediction.

6. When to Use the Supply-and-Demand Model

As we've seen, supply-and-demand theory can help us to understand and predict real world events in many markets. Through Section 10, we discuss competitive markets in which the supply-and-demand model is a powerful tool for predicting what will happen to market equilibrium if underlying conditions-tastes, incomes, and prices of inputs-change. The types of markets for which the supply-and-demand model is useful are described at length in these sections, particularly in Sections 8 and 9.

Briefly, this model is applicable in markets in which:

¦ Everyone is a price taker. Because no consumer or firm is a very large part of the market, no one can affect the market price. Easy entry of firms into the market, which leads to a large number of firms, is usually necessary to ensure that firms are price takers.

¦ Firms sell identical products. Consumers do not prefer one firm's good to another.

¦ Everyone has full information about the price and quality of goods. Consumers know if a firm is charging a price higher than the price others set, and they know if a firm tries to sell them inferior-quality goods.

¦ Costs of trading are low. It is not time-consuming, difficult, or expensive for a buyer to find a seller and make a trade or for a seller to find and trade with a buyer.

Markets with these properties are called perfectly competitive markets.

In a market with many firms and consumers, no single firm or consumer is a large enough part of the market to affect the price. If you stop buying bread or if one of the many thousands of wheat farmers stops selling the wheat used to make the bread, the price of bread will not change. Consumers and firms are price takers: They cannot affect the market price.

In contrast, if a market has only one seller of a good or service--a monopoly (see Section 11)--that seller is a price setter and can affect the market price. Because demand curves slope downward, a monopoly can increase the price it receives by reducing the amount of a good it supplies. Firms are also price setters in an oligopoly-a market with only a small number of firms-or in markets where they sell differentiated products so that a consumer prefers one product to another (see Section 13). In markets with price setters, the market price is usually higher than that predicted by the supply-and-demand model. That doesn't make the model generally wrong. It means only that the supply-and-demand model does not apply to markets with a small number of sellers or buyers. In such markets, we use other models.

If consumers have less information than a firm, the firm can take advantage of consumers by selling them inferior-quality goods or by charging a much higher price than that charged by other firms. In such a market, the observed price is usually higher than that predicted by the supply-and-demand model, the market may not exist at all (consumers and firms cannot reach agreements), or different firms may charge different prices for the same good (see Section 19).

The supply-and-demand model is also not entirely appropriate in markets in which it is costly to trade with others because the cost of a buyer finding a seller or of a seller finding a buyer is high. Transaction costs are the expenses of finding a trading partner and making a trade for a good or service other than the price paid for that good or service. These costs include the time and money spent to find someone with whom to trade. For example, you may have to pay to place a newspaper advertisement to sell your gray 1999 Honda with 137,000 miles on it. Or you may have to go to many stores to find one that sells a shirt in exactly the color you want, so your transaction costs include transportation costs and your time. The labor cost of filling out a form to place an order is a transaction cost. Other transaction costs include the costs of writing and enforcing a contract, such as the cost of a lawyer's time. Where transaction costs are high, no trades may occur, or if they do occur, individual trades may occur at a variety of prices (see Sections 12 and 19).

Thus, the supply-and-demand model is not appropriate in markets with only one or a few firms (such as electricity), differentiated products (movies), consumers who know less than sellers about quality or price (used cars), or high transaction costs (nuclear turbine engines). Markets in which the supply-and-demand model has proved useful include agriculture, finance, labor, construction, services, wholesale, and retail.

transaction costs----the expenses of finding a trading partner and making a trade for a good or service beyond the price paid for that good or service

===========

Challenge Solution

Quantities and Prices of Genetically Modified Foods

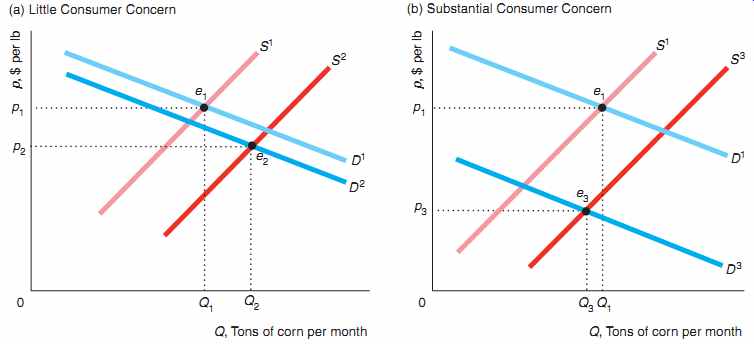

We conclude this section by returning to the challenge posed at its beginning where we asked about the effects on the price and quantity of a crop, such as corn, from the introduction of GM seeds. The supply curve shifts to the right because GM seeds produce more output than traditional seeds, holding all else constant. If consumers fear GM products, the demand curve for corn shifts to the left. We want to deter mine how the after-GM equilibrium compares to the before-GM equilibrium. When an event shifts both curves, then the qualitative effect on the equilibrium price and quantity may be difficult to predict, even if we know the direction in which each curve shifts. Changes in the equilibrium price and quantity depend on exactly how much the curves shift. In our analysis, we want to take account of the possibility that the demand curve may shift only slightly in some countries where consumers don't mind GM products but substantially in others where many consumers fear GM products.

In the figure, the original, before-GM equilibrium, e1, is determined by the inter section of the before-GM supply curve, S1 , and the before-GM demand curve, D1 , at price p1 and quantity Q1. Both panels a and b of the figure show this same equilibrium. After GM seeds are introduced, the supply curve, S2 , shifts to the right of the original supply curve, S1 in both panels.

Panel a shows the situation if consumers have little concern about GM crops, so that the new demand curve, D2 , lies only slightly to the left of the original demand curve, D1. In panel b, where consumers are greatly concerned about GM crops, the new demand curve D3 lies substantially to the left of D1.

In panel a, the new equilibrium e2 is determined by the intersection of S2and D2. In panel b, the new equilibrium e3 reflects the intersection of S2 and D3. The equilibrium price falls from p1 to p2 in panel a and to p3 in panel b. However, the equilibrium quantity rises from Q1 to Q2 in panel a, but falls to Q3 in panel b. That is, the price falls in both cases, but the quantity may rise or fall depending on how much the demand curve shifts. Thus, whether growers in a country decide to adopt GM seeds turns crucially on consumer resistance to these new products.

(a) Little Consumer Concern (b) Substantial Consumer Concern

==========

Summary

1. Demand. The quantity of a good or service demanded by consumers depends on their tastes, the price of a good, the price of goods that are substitutes and complements, their income, information, government regulations, and other factors. The Law of Demand- which is based on observation-says that demand curves slope downward. The higher the price, the less of the good is demanded, holding constant other factors that affect demand. A change in price causes a movement along the demand curve. A change in income, tastes, or another factor that affects demand other than price causes a shift of the demand curve. To get a total demand curve, we horizontally sum the demand curves of individuals or types of consumers or countries. That is, we add the quantities demanded by each individual at a given price to get the total demanded.

2. Supply. The quantity of a good or service supplied by firms depends on the price, costs, government regulations, and other factors. The market supply curve need not slope upward but usually does. A change in price causes a movement along the supply curve. A change in a government regulation or the price of an input causes a shift of the supply curve. The total supply curve is the horizontal sum of the supply curves for individual firms.

3. Market Equilibrium. The intersection of the demand curve and the supply curve determines the equilibrium price and quantity in a market. Market forces- actions of consumers and firms-drive the price and quantity to the equilibrium levels if they are initially too low or too high.

4. Shocking the Equilibrium. A change in an under lying factor other than price causes a shift of the supply curve or the demand curve, which alters the equilibrium. For example, if the price of tomatoes rises, the demand curve for avocados shifts out ward, causing a movement along the supply curve and leading to a new equilibrium at a higher price and quantity. If changes in these underlying factors follow one after the other, a market that adjusts slowly may stay out of equilibrium for an extended period.

5. Equilibrium Effects of Government Interventions. Some government policies-such as a ban on imports-cause a shift in the supply or demand curves, thereby altering the equilibrium. Other government policies-such as price controls or a minimum wage- cause the quantity supplied to be greater or less than the quantity demanded, leading to persistent excesses or shortages.

6. When to Use the Supply-and-Demand Model. The supply-and-demand model is a powerful tool to explain what happens in a market or to make predictions about what will happen if an underlying factor in a market changes. This model, however, is applicable only in markets with many buyers and sellers; identical goods; certainty and full information about price, quantity, quality, incomes, costs, and other market characteristics; and low transaction costs.

Questions

All questions' answer will be posted soon; A = algebra problem.

1. Demand

1.1 The estimated demand function (Moschini and Meilke, 1992) for Canadian processed pork is Q = 171 - 20p + 20pb + 3pc + 2Y, where Q is the quantity in million kilograms (kg) of pork per year, p is the dollar price per kg (all prices cited are in Canadian dollars), pb is the price of beef per kg, pc is the price of chicken in dollars per kg, and Y is average income in thousands of dollars. What is the demand function if we hold pb, pc, and Y at their typical values during the period studied: pb = 4, pc = 31 3, and Y = 12.5? A

1.2 Using the estimated demand function for processed pork from Question 1.1, show how the quantity demanded at a given price changes as per capita income, Y, increases by $100 a year. A

1.3 Using the estimated demand function for processed pork from Question 1.1, suppose that the price of beef, pb, rises from $4 to $5.20. In what direction and by how much does the demand curve for processed pork shift? A

1.4 Given the inverse demand function for pork (Question 1.1) is p = 14.30 - 0.05Q, how much would the price have to rise for consumers to want to buy 2 million fewer kg of pork per year? (Hint: See Solved Problem 1.) A

1.5 Given the estimated demand function Equation 2 for avocados, Q = 104 - 40p + 20pt + 0.01Y, show how the demand curve shifts as per capita income, Y, increases by $1,000 a year. Illustrate this shift in a diagram. A

1.6 The food and feed demand curves used in the Application "Summing the Corn Demand Curves" were estimated by McPhail and Babcock (2012) to be Qfood = 1,487 - 22.1p and Qfeed = 6,247.5 - 226.7p, respectively. Mathematically derive the total demand curve, which the Application's figure illustrates. (Hint: Remember that the demand curve for feed is zero at prices above $27.56.) A

1.7 Suppose that the inverse demand function for movies is p = 120 - Q1 for college students and p = 120 - 2Q2 for other town residents. What is the town's total demand function (Q = Q1 + Q2 as a function of p)? Use a diagram to illustrate your answer. (Hint: See the Application "Summing the Corn Demand Curves.") A

1.8 Duffy-Deno (2003) estimated the demand functions for broadband service are Qs = 15.6p-0.563 for small firms and Q1= 16.0p-0.296 for larger ones, where price is in cents per kilobyte per second and quantity is in millions of kilobytes per second (Kbps). What is the total demand function for all firms? (Hint: See the Application "Summing the Corn Demand Curves.") A

2. Supply

*2.1 The estimated supply function (Moschini and Meilke, 1992) for processed pork in Canada is Q = 178 + 40p - 60ph, where quantity is in millions of kg per year and the prices are in Canadian dollars per kg. How does the supply function change if the price of hogs doubles from $1.50 to $3 per kg? A

2.2 Use Equation 2.6, the estimated supply function for avocados, Q = 58 + 15p - 20pf, to determine how much the supply curve for avocados shifts if the price of fertilizer rises by $1.10 per lb. Illustrate this shift in a diagram.

2.3 If the supply of rice from the United States is Qa = a + bp, and the supply from the rest of the world is Qr = c + ep, what is the world supply? A

2.4 How would the shape of the total supply curve in Solved Problem 2 change if the U.S. domestic supply curve hit the vertical axis at a price above p?

3. Market Equilibrium

3.1 Use a supply-and-demand diagram to explain the statement "Talk is cheap because supply exceeds demand." At what price is this comparison being made?

3.2 Every house in a small town has a well that provides water at no cost. However, if the town wants more than 10,000 gallons a day, it has to buy the extra water from firms located outside of the town. The town currently consumes 9,000 gallons per day.

a. Draw the linear demand curve.

b. The firms' supply curve is linear and starts at the origin. Draw the market supply curve, which includes the supply from the town's wells.

c. Show the equilibrium. What is the equilibrium quantity? What is the equilibrium price? Explain.

3.3 A large number of firms are capable of producing chocolate-covered cockroaches. The linear, upward sloping supply curve starts on the price axis at $6 per box. A few hardy consumers are willing to buy this product (possibly to use as gag gifts). Their linear, downward-sloping demand curve hits the price axis at $4 per box. Draw the supply and demand curves. Does this market have an equilibrium at a positive price and quantity? Explain your answer.

3.4 The estimated Canadian processed pork demand function (Moschini and Meilke, 1992) is Q = 171 - 20p + 20pb + 3pc + 2Y (see Question 1.1), and the supply function is Q = 178 + 40p - 60ph (see Question 2.1). Solve for the equilibrium price and quantity in terms of the price of hogs, ph; the price of beef, pb; the price of chicken, pc; and income, Y. If ph = 1.5 (dollars per kg), pb = 4 (dollars per kg), pc = 31 3 (dollars per kg), and Y = 12.5 (thousands of dollars), what are the equilibrium price and quantity?

*3.5 The demand function for a good is Q = a - bp, and the supply function is Q = c + ep, where a, b, c, and e are positive constants. Solve for the equilibrium price and quantity in terms of these four constants. A

*3.6 Green et al. (2005) estimated the supply and demand curves for California processing tomatoes.

The supply function is ln(Q) = 0.2 + 0.55 ln(p), where Q is the quantity of processing tomatoes in millions of tons per year and p is the price in dollars per ton. The demand function is ln(Q) = 2.6 - 0.2 ln(p) + 0.15 ln(pt), where pt is the price of tomato paste (which is what processing tomatoes are used to produce) in dollars per ton. In 2002, pt = 110. What is the demand function for processing tomatoes, where the quantity is solely a function of the price of processing tomatoes? Solve for the equilibrium price and quantity of processing tomatoes (explain your calculations, and round to two digits after the decimal point). Draw the supply and demand curves (note that they are not straight lines), and label the equilibrium and axes appropriately. A

4. Shocking the Equilibrium

4.1 The United States is increasingly outsourcing jobs to India: having the work done in India rather than in the United States. For example, the Indian firm Tata Consultancy Services, which provides information technology services, increased its workforce by 70,000 workers in 2010 and expected to add 60,000 more in 2011 ("Outsourcing Firm Hiring 60,000 Workers in India," San Francisco Chronicle, June 16, 2011). As a result of increased outsourcing, wages of some groups of Indian skilled workers have increased substantially over the years. Use a supply and-demand diagram to explain this outcome.

4.2 The major BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico substantially reduced the harvest of shrimp and other seafood in the Gulf, but had limited impact on the prices that U.S. consumers paid in 2010 (Emmeline Zhao, "Impact on Seafood Prices Is Limited," Wall Street Journal, June 20, 2010). The reason was that the United States imports about 83% of its seafood and only 2% of domestic supplies come from the Gulf. Use a supply-and-demand diagram to illustrate what happened.

4.3 The U.S. supply of frozen orange juice comes from Florida and Brazil. What is the effect of a freeze that damages oranges in Florida on the price of frozen orange juice in the United States and on the quantities of orange juice sold by Floridian and Brazilian firms? 4.4 Use supply-and-demand diagrams to illustrate the qualitative effect of the following possible shocks on the U.S. avocado market.

a. A new study shows significant health benefits from eating avocados.

b. Trade barriers that restricted avocado imports from Mexico are eliminated ("Free Trade Party Dip," Los Angeles Times, February 6, 2007).

c. A recession causes a decline in per capita income.

d. Genetically modified avocado plants that allow for much greater output or yield without increasing cost are introduced into the market.

4.5 Increasingly, instead of advertising in newspapers, individuals and firms use Web sites that offer free or inexpensive classified ads, such as ClassifiedAds.com, Craigslist.org, Realtor.com, Jobs.com, Monster.com, and portals like Google and Yahoo. Using a supply and-demand model, explain what will happen to the equilibrium levels of newspaper advertising as the use of the Internet grows. Will the growth of the Internet affect the supply curve, the demand curve, or both? Why?

4.6 Ethanol, a fuel, is made from corn. Ethanol production increased 5.5 times from 2000 to 2008 and another 34% from 2008 to February 2013 (www.ethanolrfa.org). Show the effect of this increased use of corn for producing ethanol on the price of corn and the consumption of corn as food using a supply-and-demand diagram.

4.7 The demand function for roses is Q = a - bp, and the supply function is Q = c + ep + ft, where a, b, c, e, and f are positive constants and t is the aver age temperature in a month. Show how the equilibrium quantity and price vary with temperature.

(Hint: See Solved Problem 2.3.) A

4.8 Using the information in Question 3.6, determine how the equilibrium price and quantity of processing tomatoes change if the price of tomato paste falls by 10%. (Hint: See Solved Problem 2.3.) A

4.9 Use the demand and supply functions for avocado, Equations 2.2 and 2.6, to derive the new equilibria in FIG. 7.

5. Equilibrium Effects of Government Interventions

5.1 The Application "Occupational Licensing" analyzed the effect of exams in licensed occupations given that their only purpose was to shift the supply curve to the left. How would the analysis change if the exam also raised the average quality of people in that occupation, thereby also affecting demand?

*5.2 Is it possible that an outright ban on foreign imports will have no effect on the equilibrium price? (Hint: Sup pose that imports occur only at relatively high prices.)

5.3 In 2002, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service pro posed banning imports of beluga caviar to protect the beluga sturgeon in the Caspian and Black seas, whose sturgeon populations had fallen 90% in the last two decades. The United States imports 60% of the world's beluga caviar. On the world's legal whole sale market, a kilogram of caviar costs an average of $500, and about $100 million worth is sold per year.

What effect would the U.S. ban have on world prices and quantities? Would such a ban help protect the beluga sturgeon? (In 2005, the service decided not to ban imports.) (Hint: See Solved Problem 2.4.)

5.4 What is the effect of a quota Q 7 0 on equilibrium price and quantity? (Hint: Carefully show how the total supply curve changes. See Solved Problem 2.4.)

5.5 A group of American doctors have called for a limit on the number of foreign-trained physicians per mitted to practice in the United States. What effect would such a limit have on the equilibrium quantity and price of doctors' services in the United States? How are American-trained doctors and consumers affected? (Hint: See Solved Problem 2.4.)

5.6 Usury laws place a ceiling on interest rates that lenders such as banks can charge borrowers. Low-income households in states with usury laws have significantly lower levels of consumer credit (loans) than comparable households in states without usury laws. Why? (Hint: The interest rate is the price of a loan, and the amount of the loan is the quantity measure.)

5.7 The Thai government actively intervenes in markets (Nophakhun Limsamarnphun, "Govt Imposes Price Controls in Response to Complaints," The Nation, May 12, 2012).

a. The government increased the daily minimum wage by 40% to Bt300 (300 bahts ˜ $9.63).

Show the effect of a higher minimum wage on the number of workers demanded, the supply of workers, and unemployment if the law is applied to the entire labor market.

b. Show how the increase in the minimum wage and higher rental fees at major shopping malls and retail outlets affected the supply curve of ready-to-eat meals. Explain why the equilibrium price of a meal rose to Bt40 from Bt30.

c. In response to complaints from citizens about higher prices of meals, the government imposed price controls on ten popular meals. Show the effect of these price controls in the market for meals.

d. What is the likely effect of the price controls on meals on the labor market?

5.8 Some cities impose rent control laws, which are price controls or limits on the price of rental accommodations (apartments, houses, and mobile homes). As of 2012, New York City alone had approximately one million apartments under rent control. In a supply-and-demand diagram, show the effect of the rent control law on the equilibrium rental price and quantity of New York City apartments, and show the amount of excess demand.

5.9 After a major disaster such as the Los Angeles earthquake and hurricanes such as Katrina, retailers often raise the price of milk, gasoline, and other staples because supplies have fallen. In some states, the government forbids such price increases. What is the likely effect of such a law?

5.10 Suppose that the government imposes a price sup port (price floor) on processing tomatoes at $65 per ton. The government will buy as much as farmers want to sell at that price. Thus, processing firms pay $65. Use the information in Question 3.6 to determine how many tons of tomatoes firms buy and how many tons the government buys. Illustrate your answer in a supply-and-demand diagram.

(Hint: See Solved Problem 2.5.) A

6. When to Use the Supply-and-Demand Model

6.1 Are predictions using the supply-and-demand model likely to be reliable in each of the following markets? Why or why not?

a. Apples.

b. Convenience stores.

c. Electronic games (a market with three major firms).

d. Used cars.

7. Challenge

7.1 Humans who consume beef products made from diseased animal parts can develop mad cow disease (bovine spongiform encephalopathy, or BSE, a new variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease), a deadly affliction that slowly eats holes in sufferers' brains.

The first U.S. case, in a cow imported from Canada, was reported in December 2003. As soon as the United States revealed the discovery of the single diseased cow, more than 40 countries slapped an embargo on U.S. beef, causing beef supply curves to shift to the left in those importing countries, and at least initially a few U.S. consumers stopped eating beef. (Schlenker and Villas-Boas, 2009, found that U.S. consumers regained confidence and resumed their earlier levels of beef buying within three months.) In the first few weeks after the U.S. ban, the quantity of beef sold in Japan fell substantially, and the price rose. In contrast, in January 2004, three weeks after the first discovery, the U.S. price fell by about 15% and the quantity sold increased by 43% over the last week in October 2003. Use supply-and-demand diagrams to explain why these events occurred.

7.2 In the previous question, you were asked to illustrate why the mad cow disease announcement initially caused the U.S. equilibrium price of beef to fall and the quantity to rise. Show that if the supply and demand curves had shifted in the same directions as above but to greater or lesser degrees, the equilibrium quantity might have fallen. Could the equilibrium price have risen?

7.3 Due to fear about mad cow disease, Japan stopped importing animal feed from Britain in 1996, beef imports and processed beef products from 18 countries including EU members starting in 2001, and similar imports from Canada and the United States in 2003. After U.S. beef imports were banned, McDonald's Japan and other Japanese importers replaced much of the banned U.S. beef with Australian beef, causing an export boom for Australia ("China Bans U.S. Beef," cnn.com, December 24, 2003; "Beef Producers Are on the Lookout for Extra Demand," abc.net.au, June 13, 2005). Use supply and demand curves to show the impact of these events on the domestic Australian beef market.

7.4 When he was the top American administrator in Iraq, L. Paul Bremer III set a rule that upheld Iraqi law: anyone 25 years and older with a "good reputation and character" could own one firearm, including an AK-47 assault rifle. Iraqi citizens quickly began arming themselves. Akram Abdulzahra has a revolver handy at his job in an Internet cafe. Haidar Hussein, a Baghdad book seller, has a new fully automatic assault rifle. After the bombing of a sacred Shiite shrine in Samarra at the end of February 2006 and the subsequent rise in sectarian violence, the demand for guns increased, resulting in higher prices. The aver age price of a legal, Russian-made Kalashnikov AK-47 assault rifle jumped from $112 to $290 from February to March 2006, and the price of bullets shot up from 24¢ to 33¢ each (Jeffrey Gettleman, "Sectarian Suspicion in Baghdad Fuels a Seller's Market for Guns," New York Times, April 3, 2006). This increase occurred despite the hundreds of thousands of firearms and millions of rounds of ammunition that American troops had been providing to Iraqi security forces, some of which eventually ended up in the hands of private citizens. Use a graph to illustrate why prices rose.

Did the price have to rise, or did the rise have to do with the shapes of and relative shifts in the demand and supply curves?

7.5 The prices received by soybean farmers in Brazil, the world's second-largest soybean producer and exporter, tumbled 30%, in part because of China's decision to cut back on imports and in part because of a bumper soybean crop in the United States, the world's leading exporter (Todd Benson, "A Harvest at Peril," New York Times, January 6, 2005, C6). In addition, Asian soy rust, a deadly crop fungus, is destroying large quantities of the Brazilian crops.

a. Use a supply-and-demand diagram to illustrate why Brazilian farmers are receiving lower prices.

b. If you knew only the direction of the shifts in both the supply and the demand curves, could you predict that prices would fall? Why or why not?

PREV. | NEXT

top of page Similar Articles Home