There’s a certain economic appeal to the idea of free firewood, and a roman tic appeal to the idea of cutting your own. But don’t let these notions blind you to the reality—this is not a sport for the faint-hearted. If you’re going to at tack anything larger than a 12- or 15- inch-diameter tree, or if you plan to hew a small grove in a day, you are going to earn your satisfaction, whether you use an axe or a chainsaw. You can, how ever, make your work easier and safer by following some simple precautions.

1. Wear clothing that fits just right— loose enough to keep your limbs free, yet tight enough not to get caught on branches or your own tools.

2. Wear goggles or an eye shield.

3. Wear a hard hat. Dead limbs that fall from trees while you are beneath them are called “widow makers.”

4. Wear ear plugs if you’re working with a chainsaw.

5. Wear heavy boots with steel- capped toes and non-skid soles, and try to keep them out of the way of rolling and falling logs.

6. Have company—always cut with another person present. If you’ve never felled trees before, choose a partner who has.

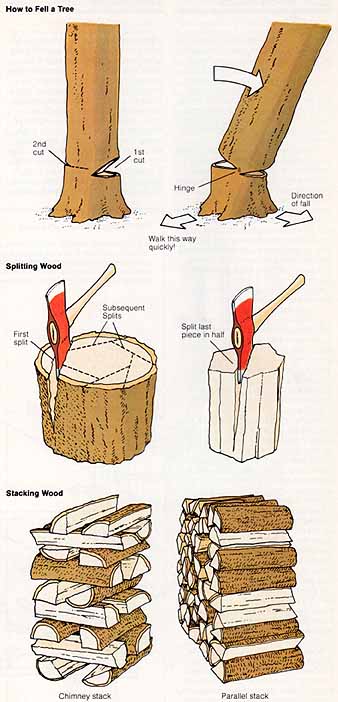

• How to fell a tree: First make a wedge-shaped cut on the side of the trunk toward which you expect the tree to fall. Make a second cut on the other side of the tree slightly above the apex of the wedge. As the second cut nears the first, the tree will fall pivoting on the “hinge” of wood left between the cuts. When the tree starts to fall, get away from the direction of the fall as quickly as possible. Falling trees are not always predictable, but they tend to leap up and back when they hit the ground.

After the tree has fallen and you have trimmed off the crown and small branches, limb the tree by removing the larger branches. Then cut the boughs and trunk into firebox-size pieces. This process is known as bucking.

You should buck your tree as soon after felling it as possible, because if it lies around on the ground for very long it will take up moisture and begin to rot. For the same reason, you should split and stack your logs for seasoning as soon as possible after bucking.

• Splitting: Splitting can be a lot of fun (unless you’ve felled an elm or some other split-resistant tree), and is really what most people have in mind when they envision cutting their own firewood.

In general, split between knots, rather than through them; along cracks, if there are any; green wood (it will split more easily than seasoned wood); light, straight-grained wood (it will split more easily than heavy wood with a wavering grain); and frozen wood (it will split more easily than unfrozen wood). If you’ve felled and bucked in late autumn, you might want to stack your un split wood, and simply split it as you need it after the weather turns freezing. Don’t bother trying to split logs where large branches grew from the trunk— they’ll almost never split, and in any case they will be too wide for use in most fireboxes.

Large, thick logs will be difficult to split by axe, and may require the use of a maul, which is like a blunt-tipped axe. Because of the shape and extra weight of the head, mauls force wood apart rather than cutting it.

Use some sort of chopping block when you split wood—the ground itself will dull your axe faster than you can chop wood. An old stump is excellent for this purpose if it is fairly low (about 15 to 20 inches high). Stand the log to be split on the block and examine it to be sure you won’t be chopping through knots, which are cross-grained to your cutting angle, and very hard to split. Then split off the edges of the log into four or more pieces, leaving the bark- less center. When this core is small enough, split it straight down the center. If your pieces get very small, just put them in the kindling bin.

• Stacking: Once you’ve split your logs, stack them to dry out, or season. Obviously, you’ll make it easy for yourself if you stack your wood near the door you’ll be using to carry it to your firebox. Just make sure to keep it separate from the exterior walls of your house; insects are likely to be inhabiting the split logs. If you can find a small rise on which to locate your pile, do so—the ground underneath it will stay dryer than would the ground under a depression, which might collect water. Exposure to air and sun will speed the seasoning process.

Split wood will dry fastest in a chimney formation. Place two logs parallel to each other and less than one log’s- width apart. Then put two more logs on top of the first two, but set them at right angles. Continue with the next two at right angles again (paralleling the formation of the first two), and so on up the stack. Ordinary parallel or cross-stacking occupies less space than chimney stacking, but it doesn’t let air circulate as freely among the logs. Don’t make a chimney stack too high; it might topple in a strong wind. Ideally, you will let your wood dry for a year, but you can burn it successfully before that.

Once your stacked wood is almost dry, cover it to protect it against snow, rain, and ice. A tarp or a sheet of heavy plastic works well. Don’t make an air tight seal—air should be able to continue to circulate, even when the wood pile is dry.

How to Fell a Tree: Direction of fall, quickly walk this way; Splitting

wood: Split last piece in half; Stacking wood: Chimney

stack vs. Parallel stack

Next: How Wood Burns

Prev: Cutting Your Own Wood