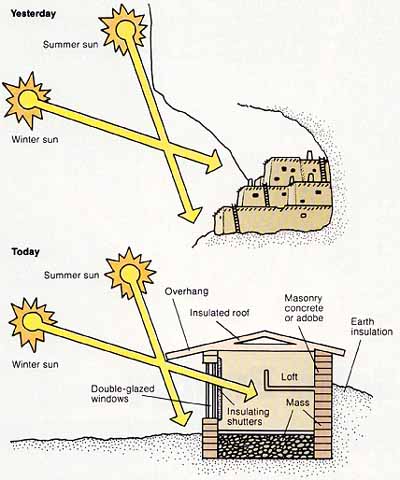

The presence of solar energy has never been in doubt. The Pueblo Indians of North America used their adobe huts as mass to absorb that energy during the heat of the day, and to radiate it back to the inhabitants during the chill desert nights. In about 400 B.C., the Greek philosopher Socrates recommended that houses be built with their south sides raised to embrace the sun’s heat, and their north sides lowered to keep cold winter winds at bay.

The scientific application of solar energy was under way by 1774, when Joseph Priestley discovered oxygen by focusing the sun’s rays onto mercuric oxide; and Antoine Lavoisier, known as the father of modern chemistry, also used large glass lenses to focus the sun’s power in the 1770s.

But as Ken Butti and John Perlin point out in their guide, A Golden Thread, the first significant step in making solar power commercially available did not take place until April 28, 1891, when Clarence M. Kemp, a manufacturer from Baltimore, Maryland, patented his Climax solar water heater.

The Climax, designed to be mounted on a roof or wall, was functionally identical to solar water heaters made for home use today. It was made of a galvanized iron water tank, painted black and set inside an insulated box covered with glass. By painting his tanks a dark color, Kemp enhanced their power as solar collectors; by insulating the box, he minimized conductive heat loss; and by covering the tanks with glass, he trapped the collected heat.

Kemp sold his patent to a pair of Californians named Brooks and Congers in 1895. These two Pasadena business men marketed the product to about a third of their fellow townfolk; then, along with a competitor called Day and Night, they entered the markets in Arizona, Florida, and the Hawaiian Islands.

The solar water heater was received enthusiastically, not as a radical means of harnessing energy, but rather as an efficient one. Its success in its first markets was due partly to the relative frequency of sunny days, and partly to the high cost of other fuels.

Early in the 20th century, coal was the principal fuel used in the United States. But California had little coal of its own; and imported coal cost twice what it cost elsewhere in the country. Natural gas production was still in its infancy, and gas cost about ten times what it costs today. Needless to say, electricity—which relies for its production on other fuels—was prohibitively expensive.

In this market, solar heating was relatively cheap, renewable, and easy to obtain. Other experiments were going on elsewhere in the world, including a 50 horsepower solar steam engine built near Cairo, Egypt, and a solar-distilling operation in Chile that produced 6000 gallons a day of fresh water from salt water. But through the 1920s and 1 930s, the development of solar energy took place largely in the US—principally in Florida and California, and mainly concentrating on water heating. In the 1940s, however, the US was gearing up to participate in World War II, and prohibited the nonmilitary use of copper. Since plastics technology was relatively unsophisticated at that time, and only copper pipes could resist corrosion and be useful in a solar system, the progress of solar energy technology ground to a halt. By the end of the war, cheap alternative energies—gas, oil, and electricity —discouraged its further exploration, except as a topic of academic discussion.

In the 1980s, we find ourselves looking back on the earlier days of fossil fuels to see what we can learn from them. and solar energy is making a strong comeback. Throughout Europe, the market for solar hardware is booming. In West Germany in 1975, for instance, no companies were in that business; but by 1977, five hundred companies reckoned their sales at more than $20 million. The French were only slightly behind, projecting 200,000 homes and offices using solar energy by 1 981. In the United States, the number of various solar systems in operation is approaching 500,000; and with increasing government support, solar installations are becoming more familiar and available.

The Department of Energy budget for 1981 established the Solar Energy In formation Data Bank, whose purpose is “to collect, review, and disseminate in formation for all solar technologies.” Solar application programs include a variety of incentives, such as tax credits for investments by residential users in solar energy equipment to heat or cool buildings. Direct subsidies for conservation loans to owners of residential buildings using solar energy are keeping some payments very low. There are also considerable incentives at the state level in almost every state.

Yesterday (Winter sun); Today (Summer sun)

Next: Collection, Storage and Distribution of Solar Energy

Prev: Intro