How to do a Home Energy Audit

Your house is about to be audited—not by the IRS, by you. Doing a walk-through energy inspection of your home will give you a good idea of the shape it’s in, energy-wise. You’ll be looking around, taking notes, checking off answers to questions, and even scribbling a few drawings, where appropriate. This audit will show you what your house needs, and where. Later, you can use the material in the rest of this guide to sort out your priorities about energy-saving amendments, and then install (or have installed) the ones you choose.

To find out how well your home is being heated or cooled, get out a pen, pa per, a clipboard, and this guide. (Before you actually begin your walk, read through this section, including “A Simple Checklist”.) You’ll need to make a map of your house. You can use plain paper or graph paper. If you use the latter, let one small square equal one foot of your floorspace (two feet if your house is very large). Mea sure the length, width, and height of each room. Include every wall, door, window, and special feature of each area you’ll be walking through—the out side; the general living space (living room, bedrooms, kitchen, bathroom, and so forth); the attic; and the basement.

This audit will take place outside, in side, and in-between. Carry your map with you, and make notes and brief sketches on it in the appropriate places.

Outside

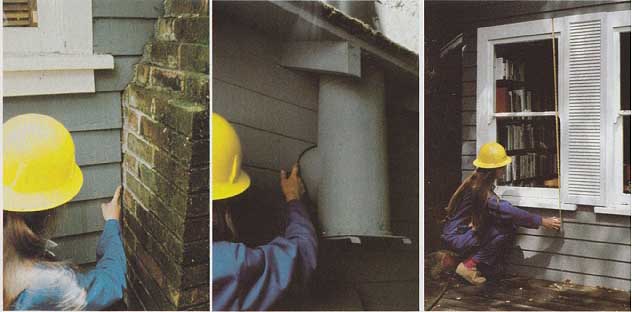

• Cracks and Joints: Walk completely around your house and look for cracks in the wall or joints. Pay special attention wherever two different kinds of building materials meet—where a concrete foundation joins wooden or aluminum siding; where a window or a door frame fits into a wall; where the roof joins the siding; and especially where the siding meets a chimney. If there are holes meant to accommodate wiring, pipes, ductwork, tubes, or hoses, check to make sure the holes aren’t larger than they should be. These cracks should be filled with caulk to eliminate energy leaks through them. In some cases, they may have been caulked before. Check to see if the caulking needs to be replaced or if the seal is still intact. Complete instructions for caulking can be found elsewhere in this guide.

• Landscaping: Surprisingly, what’s out side your house affects your comfort inside it. Are you on a hill or slope, protected from wind or in its direct path? Do you have mature trees on your property? If so, how tall are they? Where are the trees located? Do they block northerly or southerly winds? How far away from the house are they? Do you have immature trees that will grow? To what height? Are the trees deciduous (lose their leaves in spring) or evergreen (keep their leaves year round)?

Is there shrubbery next to the house? Are there vines on or next to the house? Note all these details, sketching the greenery in on your map. Do you have places that are particularly battered by winds—doorways, or one side of the house? Do you have fences anywhere? How high are they and where are they located? What direction is it from the house? The answers to these questions will help you determine what landscaping alterations you can make to help conserve energy. Details on how to assess these factors are elsewhere in this guide.

In-Between

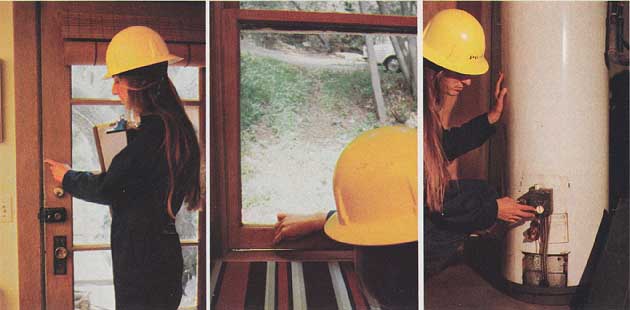

• Doors and windows: Between the in side and the outside of your house are the doors and windows. They are a major source of heat loss, around their edges and through their glass. If your house is typical of most American homes there’s little or no filler for the cracks around these openings. All these big, heat-devouring holes in your walls should be sealed along the top, bottom, and sides so that, when closed, they fit tightly against their jambs. Weather-strip ping is the name of the game, here, and all the how-to’s are discussed later. If, when checking your doors and windows, you find existing weatherstripping, note whether it is in good repair or needs to be replaced.

Now look at the glass on your windows and all doors to the outside. Are they single pane or double pane? Are there storm windows or doors? As you draw each window onto the map of your house, note what kind of window it is; whether it faces north, south, east, or west (you can approximate, if need be); how many windows face in each direction; and what amendments currently exist around the window—awnings, over hangs, curtains, shades, shutters, and so forth. Later on, you’ll learn how to turn any such amendment into an energy-conserving advantage.

Other things to look out for are: Which windows admit the most light? Which admit the least light? Which let in the sun? Which don’t? Which have views you want to keep? Which don’t? This in formation will help you decide what changes to make at your windows.

Inside

• Fireplace and chimney: A fireplace and chimney may seem romantic, but what they really amount to is a large hole in your ceiling, through which a huge amount of heat escapes. A fire place loses about as much heat as it produces if you use it often; and if you use it only now and then, it loses even more heat. From a conservation stand point, your best bet is to just plug it up.

However, if you don’t want to do that— or if you use your fireplace enough to warrant keeping it unplugged—there are a few things you can do to keep the heat indoors.

First see if you have a damper, one that fits snugly into the flue. What kind of fireplace screen do you have—wire mesh, glass? Is your fireplace vented to the outside? Check for ducts in the floor or on the wall. Do they work? Is your chimney clean? Section 6 outlines the ways you can maintain your fire place and make it as energy-efficient as possible.

• Heating system: Now turn on your heating system and check each outlet for heat. Are there any that don’t seem to be working? If you have forced-air heating and some room is not getting warm air through its duct, the answer to your problem may be in the furnace or in the venting system itself. Are the heating vents free of dust and dirt? Make a note to clean them if they’re not. Is your thermostat working properly? Note if you’ve had any problems with it—if you have, it should be checked by your heating service person.

• Other heat sources: As you walk through your living space, draw on your map stoves, heaters, chimneys, and recessed heating or lighting fixtures, ceiling fans, in-wall heaters, and other sources of heat. This drawing will come in handy when you get to the attic.

• Water heater: Find your water heater and put it on your map. Now write down the temperature at which you now have it set, and indicate whether or not it is insulated. (If your water heater is located in the basement, wait until you get down there.) Note also whether any of the pipes are insulated, and if the insulation is well-sealed.

• Waterbed: If you have a waterbed, draw it on the map and write down its temperature, too. A waterbed costs about $5 a month to heat. However, you can keep the expense of keeping those hundreds of gallons of water warm by letting the sun shine on it or by covering it when the sun is not shining.

Cold air can enter where cracks develop where two

building materials meet; Look for infiltration wherever ducts or other

supply systems pass through the walls; a PG and E conservation analyst

measures a window for weatherstripping.

Attic

• Proper clothing: Dress properly to audit your attic. Not black tie and tails— sturdy clothing that will protect you and that you don’t mind getting dirty. You will need:

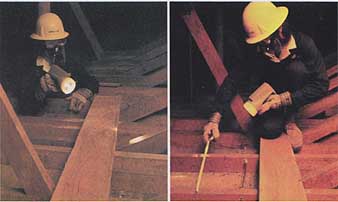

1. A hard hat. Long nails protruding from unfinished roof beams can be not only painful but downright dangerous. If you can’t get a hard hat, at least wear a loose hat that will press in on your head and let you know when you are about to bump into something.

2. Eye goggles. Wear these to protect your eyes from protruding objects and to keep out dust and other foreign particles.

3. A respirator. If your attic already has some insulation, a respirator is especially for you. Tiny particles of insulation can be extremely irritating to the lungs. Even if there’s no insulation up there yet, if you haven’t been in your attic for a while you’re going to kick up a lot of dust, and the respirator may save you from a prolonged bout of sneezing. If you don’t have a respirator, cover your mouth and nose with a handkerchief.

4. Gloves. The same particles of insulation that can irritate your lungs can also irritate your skin. Besides, you’re likely to disturb some spiders and in sects, and the wood will probably be splintery. The best type is the sturdy construction gloves available for a few dollars at any hardware store.

5. Long-legged pants and long-sleeved shirt.

6. Sturdy shoes. Nails can stick up from floors as well as down from roofs.

• Proper equipment: You’ll also need to bring along the following equipment:

1. A ladder. A good sturdy ladder is useful for reaching high ceilings, vents, and so forth.

2. A flashlight. Make sure it has batteries that work.

3. A strong board. Use this to straddle the narrow joists in the floor, if your attic is unfinished. (Or you can forego this and just stand on two joists at a time, instead.)

4. A tape measure, pencil and your map, of course. Measure your findings and note them on the map.

When doors are not sealed tight in their frames, infiltration occurs.

Doors and windows that do not close completely cost you energy dollars.

Most domestic hot water needs only require a low to medium temperature (about

120-degrees F).

• Joists: Some attics are entered through a door from a room on the top most floor. But with most attics, you climb an additional flight of stairs, and then climb a ladder to a door or hatch. If this is the case with your attic, be sure to use your flashlight. Beam it in even before you pull your whole body up there. Now, while still perching on the ladder, take a look around. Is there some sort of support to stand on? In most unfinished attics, the “floor” is nothing but joists running above the plasterboard that forms the ceilings of the rooms below. Don’t step on this plasterboard—it won’t hold your weight. and don’t stand on just a single joist—it might not hold your weight, either; or it might flex, popping nails on your ceiling boards and causing cracks below. In any case, you might lose your balance. Instead, you can stand on two joists at a time, or else bring along a strong board that’s wide enough to straddle a couple of joists, and walk on that.

Now bring yourself fully into the attic and take a look at the joists. How far apart are they? In most houses, they will be 16 inches or 24 inches apart. If yours are more than 24 inches apart (which is likely in some older houses), check to make sure that the ceiling below will stand up to the weight of new insulation.

• Roof: Now look at the inside of the roof. Note every single hole. A good way to recognize holes is that you can see daylight through them. Also look for leaks or any other sort of damage in the roof. Check around the flashing and the vent-work, as well. All roof repairs must be made before you even think of adding insulation. This is especially necessary if water has already gotten into the house, because the water will ruin your insulation as well as the structure of your house.

Be on the lookout for any signs of dry rot along the beams, where water may have gotten into the attic. Dry rot looks like a white, powdery accumulation on top of spongy, punky, softening wood. Is there any existing insulation? If so, what kind is it? How deep? (For instructions on recognizing and measuring different kinds of insulation, see our topical section.)

Make sure all recessed heating or lighting fixtures are clear. You noted them on your map when you were in the living space, and from here in the attic you should be able to spot their locations again.

When you have noted all the problems with the roof, there are other things to look for. There’s no particular order; just be sure you get them all.

• Vents: Make sure all air vents are clear and open. Make note of where the vents are so that you don’t cover them with insulation later on. The purpose of the vents in the attic is to keep the air fresh, and to keep moisture from building up (otherwise it might rot your insulation and housing structure). and in hot weather, vents keep your attic from be coming a hotbox that filters unwanted heat to your living quarters.

In fact, vents are so important that if you don’t have any, add no attic insulation until you’ve put some vents in. Al though they need not conform absolutely to federal energy standards, you should have approximately one square foot of vent for every three hundred square feet of ceiling area. There’s really no such thing as “too much” venting in a properly insulated attic, but there is such a thing as “too little.” (For more details on vents, see our topical discussion.)

• Wiring: Examine your wiring. If it’s in good condition, you can lay insulation right under it. But if it’s worn, call an electrician to tend to it before you lay any insulation. In fact, any time there’s plumbing or electrical work to do, it’s wise to enlist some expert guidance. Electricity is dangerous if you don’t know exactly what you’re about, and since both electrical and plumbing re pairs can involve the structure of your house, errors or misjudgments can be quite costly.

If your house is more than 25 years old, you may have knob and tube wiring. In this system, tubes containing the wires run through or across your joists, and you can see glazed ceramic conductors on top of them. If you hire a contractor to insulate your attic, be sure to point out the knobs and tubes. If you plan to insulate your attic yourself, when it comes time to actually lay down the insulation (which most likely will be fiberglass batts), you’ll need to stop at every tube and cut the batts to fit down next to the wiring. You’ll also need to keep the aluminum vapor barriers away from the wiring, so that you don’t short- circuit your whole house.

• Heat sources: When you went through your living space, you made note of all stoves, heaters, recessed lighting fixtures, and other sources of heat. This was so you’d know their locations well enough that you wouldn’t put the insulation too near them. Most insulation materials are flammable to one degree or another. Fiberglass isn’t flammable, but it pays to keep even this material away from heat sources. It never hurts to be too careful about safety.

So when you insulate your attic, you’ll want to install barriers around these heat-producing fixtures—especially if you’re using blow-in cellulose. This will keep loose fragments of the insulating material from falling into the fixtures, which would create a very real fire hazard. By noting all fixtures, vents, wiring, etc., you’ll know how many barriers you’ll have to build. You’ll find further in formation on insulation in a topical section.

• Vermin: Look around for signs of vermin. Like it or not, your house could be the happy home of a few families of rodents or insects. and you might as well evict them before you supply them with all that nice, warm, nest-like insulating material.

• Holes: Finally, look around in your attic for any holes that lead to living areas. These should be plugged to reduce infiltration, no matter what type of insulation you use, but they especially should be plugged if your insulation will be loose fill—otherwise the insulation will sift right through the holes.

Okay—come on down from the attic, now. (Remember to put the hatch back on.) Take off your hard hat, your goggles, your respirator, and any clothes that have gotten really dirty. Have a cup of coffee and make sure your notes are legible.

Take a look around even before you pull yourself completely up into

the attic. How far apart are your joists? In most American houses they are

16” or 24” apart.

Basement

• Furnace: The furnace is the most important part of any basement audit.

(Some furnaces are in first-floor closets instead.) Take a look at the filter. Is it clean? Look at the ductwork, especially at the joints. Is your duct tape secure, or is it damaged or missing? Are there any leaks? If you aren’t getting enough heat through one vent upstairs, it could be because some ducting is missing or broken.

You might consider having a service person check your furnace for efficiency— either now, as part of your energy audit, or later, after you’ve read through our topical discussion. If you have a gas furnace, ask the service person to show you how to turn your pilot light on and off. Turning the pilot light off completely in months when you won’t be using the furnace can save you energy as well money.

• Hot-water heater: Check your hot-water heater. Is t insulated? If its pipes run through an unheated space and there is any chance that the space may freeze, the pipes should be insulated as well. As a side benefit, that bit of insulation will reduce your waiting time for hot water when you turn on the tap.

• Ceiling: Check for insulation on the basement ceiling above you. If the basement is unfinished, consider it out side space, just like your attic or garage. You should insulate your living quarters against the cold that can seep up in winter.

• Vent holes: Finally, examine the holes where the heating vents go through to the floor above you. Sometimes they are installed so sloppily that air comes in around the vent grille. If you find this problem, note on your map that rifts here should be caulked, or stuffed with pieces of insulation.

Okay, come upstairs again. You’ve just completed the first step of your own, personal, walk-through home energy audit. Now that you know what shape your house is in, let’s see what that means in terms of energy and dollar costs and savings.

Measure the joists on the basement ceiling as you measured those

on the attic floor.

The Financial Picture

Obviously, there is no such thing as an “average” American house. Therefore, all the following figures should be taken as guidelines only.

In the average” American frame house, with no existing insulation, 30 to 35 percent of all heat loss occurs through the ceiling; 25 to 30 percent occurs through the floors; 15 to 20 per cent through the walls; 10 to 15 percent through infiltration; 10 to 15 percent through doors and windows; and about 2 percent through the ductwork.

Unless otherwise noted, the costs for energy conservation improvements listed here are for materials only. We are assuming that you will do the work your self. If you hire union labor for any of these jobs, expect to pay about $40 per hour per person for that help. If you hire a semiskilled handyperson, expect to pay about $10 per hour. If inflation continues to climb, all costs—materials and labor—are likely to do the same. Nor is there any certainty about the number of hours your employee will re quire to accomplish a given task. How long the job will take depends on the employee’s skill, partly on the nature of the job and the job site, and partly on the nature of the employer—you.

Costs will vary according to locale and the nature of your heating system. In general, costs are as follows:

Attic Insulation (fiberglass batts): 18 foot to R-11; 25 foot to R-19. (we will later explain R-values.)

Floor Insulation: Same as attic insulation.

Wall insulation: Same as attic insulation, assuming: 2 by 4 studs; open wall; and bare studding. These are unusual conditions, however. More often, the wall will be sealed and you will have to hire a contractor to blow in loose fill insulation or foam-in-place insulation. For contractor-installed, blown-in cellulose, figure $4/sq. foot. Foam-in-place (depending on the foam, the contractor, and your house) will cost more.

Plastic storm windows, including screen-type framing: $2.00/sq. foot, including frame.

Storm doors: $120 per door and up.

Weatherstripping: Flexible—$12 to $20 per door; rigid-$20 per door. The higher cost of rigid weatherstripping comes with good news and bad news. The bad news is that rigid stripping is harder and more complicated to install than flexible stripping. The good news is that it lasts far, far longer than flexible stripping, and will easily earn back its cost.

Water heater insulation: $50 per heater.

Clock (timer) thermostat: $40 to $90, plus installation.

Ductwork insulation: 50 per linear foot without air conditioning; $1 per foot with air conditioning.

Caulking: $4 to $10 per tube.

In our “average” house, the costs and savings for these energy-conserving amendments are as follows.

But your house isn’t average; most likely, you have a unique combination of circumstances that you’d like to correct or improve upon in order to save energy and money in the coming years.

Because every house and every per son’s use of energy is different from all others, there is no way we can tell you exactly what improvements to make, or exactly what they will cost, or exactly how much energy and money such improvements will save you over how long a period of time. But we can give you a general formula that will enable you to make your own, fairly accurate, assessment.

1. Add the totals of all your utility bills (both gas and electric) from the past 12 months. If you don’t have a checkbook record of the amounts, you can find out what these are by calling your utility company or companies. In your total, include any money you spent on back-up or auxiliary heating, such as wood, coal, or propane, but don’t include the price of stoves, fireplace screens, or other tools or machines.

2. Select one month when you did no heating and no cooling through any of your systems, but not a month when you were away on vacation or had all your relatives visiting. Pick an “average” month without heating or cooling. If you have no cooling system, pick a summer month; if you do have a cooling system, choose a spring or fall month.

3. Multiply that month’s utility bill(s) by 12 (for 12 months).

4. Subtract the result you got in Step 3 from your total in Step 1. The number you are left with in Step 4 is approximately what your heating and cooling costs were in the past year.

5. To find out approximately what dollar savings you can realize per year from any of the amendments we mentioned earlier, simply multiply your answer from Step 4 (your heating and cooling bill for the past year) by the savings percentage indicated for that amendment. Don’t for get the decimal point.

For instance, if the number you come up with in Step 4 is $1 000.00, and you want to know how much money you might save per year by adding attic insulation in Atlanta, multiply $1000.00 by 0.43. The answer is $430.00.

If you want to know how long it will take for your conservation improvement to pay back the money you have invested in it, simply divide your answer from the preceding paragraph ($430.00) in to the multiple ($1000.00). In this case, your answer is about 2 1/3 years, assuming your fuel costs remain stable. If your fuel costs rise, you will save more money on your conservation investment, and it will pay you back faster. For example, if your fuel costs double the day after you install attic insulation in the problem above, your savings will be closer to $860.00 than to $430.00, and your conservation investment will pay back in about 1¼ years.

Remember, these numbers are guide lines for an average house in each of the specific areas mentioned in the chart. The actual numbers you come up with, and the actual savings you achieve, may be greater or smaller than our numbers.

There is also an interactive effect, which will alter your own final, real numbers. That means that when you insulate both your ceiling and your wails, for instance, the combined savings will not equal the savings indicated for insulating the two areas separately. In other words, if you can save $200.00 per year by insulating the ceiling, your heating costs will already be lower when you start to insulate your walls, and the savings you will realize from insulating your walls will be a little bit less than the original figure projected.

Weatherizing Your Home: Savings per Year

Because the costs of materials, labor, and fuels vary from one region of the country to another; and because every house is unique, the figures below reflect general national averages for weatherizing a 1400 square foot ranch style home in 2010. Our model house begins with no insulation and is improved to R-19 ceilings and R-11 walls and floors. Except where noted, costs are for materials only. All numbers are approximations and are to be used only as guidelines.

Improvement |

Cost |

Dollar Savings/Year |

Percent Fuel Bill Savings/Year |

Attic (Ceiling) Insulation Floor Insulation Wall Insulation (Contractor Installed) Storm Windows and Doors Weatherstripping Water Heater Blanket Clock (Timer) Thermostat (10-degree F Nighttime Setback) Ductwork Insulation Caulking |

$300-$400 $300-$450 $1000-$1500 $150-$600 $20-$80 $20-$25 $30-$65 $20-$50 $20-$100 |

$100-350 $60-110 $85-150 $50-$300 $10-$50 $5-$20 $30-150 $10-$25 $10-$25 |

10%-20% 3%-5% 3%-6% 5%-10% 1%-2% 1% 1%-5% 1% 1% |

Totals |

$1860-$3270 |

$360-$1180 |

26%-51% |

A Simple Check-list for Your Walk-through Home Energy Audit

So that you won’t have to be flipping through the pages of this guide while you stand on a ladder, probing your attic ceiling for dry rot or looking up your chimney, we offer this check-list. It shows at a glance what to look for, and gives you space to make notes on your findings. Every item contained in this check-list is explained in the walk-through audit.

Outside

This includes the outside of the house, and the area around it.

Cracks and Joints: In particular, look for cracks and joints that need to be sealed with caulking compound. If caulking already exists, note whether it is in good repair (complete and without cracks), fair (mostly good but with some cracks or missing pieces), or poor (missing or badly broken).

• Are there cracks in the outer walls? Yes_______ No_______

• Where? _______

-----

Judge the following as: Good __ Fair __ Poor ___

• What is the caulking like where two or more different kinds of building materials come together?

• Where concrete foundation joins wooden, aluminum, or other siding?

• Where window or door frames fit into walls?

• Which ones? _________

• Where roof joins siding?

• Where? ______

• Where siding meets chimney?

• Where holes in roof or walls accommodate wiring, ducts, pipes, tubes, or hoses?

• Where? ___

-----

Landscaping:

• Are you on a hill or slope? Yes. No___

• What direction does your house face?

North_ South_ East__ West._

• What are the directions of the prevailing winds?

Winter___ Summer____

• Are there trees on your property? Yes____ No_____

• For each tree, or stand of trees, note the following:

What kind of tree is it? _____

How tall is it? _____

How far from the house and in what direction? ____

Is it mature or immature? ____

Is it deciduous or evergreen?

• Is there shrubbery next to the house? Yes___ No__

Are there vines next to or on the house? Yes No_______

• Are there fences on your property? Yes______ No_______

• How high are they and where are they located?______

• Do you have water on your property, such as a pond? Yes____ No___

• Where is it located? _________

-----

Swimming Pool:

• Do you have a swimming pool? Yes____ No____

• Is it heated? Yes___ No ____ By what method? _____

• Do you have a swimming pool cover? Yes__ No____

• What type?

• Is it in good repair? Yes___ No___

-----

Living Space

This includes all parts of the house in which people actually live and work. It does not include unheated garages, attics, basements, or crawlspaces.

Windows and Doors:

• Are your doors and windows weatherstripped? Yes____ No_____

What condition is the stripping in? Good__ Fair__ Poor__

Which doors and windows are not weatherstripped?

• Do you have single-glazed windows? Yes______ No_______

Where and facing in which direction? __________

• Double-glazed windows? Yes_______ No______

Where and facing in which direction? _____

• Storm windows or doors? Yes_______ No______ • What type are they?

• Where and facing in which direction? ______

• Awnings and /or overhangs? Yes_______ No_______ • Where and facing in which direction? _____

• Curtains, shades, shutters, etc.? Yes_______ No_______ • For each window, what type of covering do you have?_____

Fireplaces:

Yes ___ No______ • Size (s) • Damper? Yes______ No______ • Glass Screen? Yes No______

• Is fireplace vented to the outside? Yes_______ No_______ • Is the chimney clean? Yes No_______

Heating System: (Check any that apply.)

Furnace_______ Gas_______ Forced air_______ In-wall_______ Electric_______ Steam (radiator) Radiant ____ Oil_______ Hot water (baseboard) ___ Other (Propane, coal, wood, solar)

• Are heating vents clean? Yes____ No____ Is thermostat working properly? Yes__ No___

Water Heating System:

• Gas_______ Electric_______ Solar______ • Temperature setting? • Insulated? Yes ___ No______

• Pipes insulated? Yes_______ No_____

Attic

An upper crawlspace may be considered an attic, if that’s what your house has. By “attic,” we mean the topmost, probably unfinished, portion of your house.

• Is the attic “floor” insulated already? Yes_______ No_______ • What kind of insulation? ____ • How deep? ______

• Can you see any holes between the attic and your living space? Yes_______ No_______ • Where? ___________________________ What size?

• Can you see the joists? Yes_______ No_______ • How far apart are they? 16” 24 More than 24

• Can you see the wiring? Yes_______ No_______ • What condition is it in? Good_______ Fair_______ Poor_______

• Do you have knob and tube wiring? Yes_______ No_______ • Can you find any holes in the roof? Yes_ No__

• Where?

• Do you have any vents? Yes____ No______ How many? Where?_________ What size?

• Can you see any dry rot? Yes No_______ Where? ____________

• Are there any recessed lighting or heating fixtures that might heat up and endanger insulation? Yes_______ No_______

• What and where?

• Can you see any evidence of vermin? Yes_______ No_______ • What and where? _____________

Basement

A lower crawlspace may be considered a basement, if that’s what your house has. We use the term to designate the lowest, probably unfinished, portion of your house. If your heating plant or duct work is located somewhere other than the basement, you should still answer the questions here that pertain to it.

Furnace: • Is the filter clean?______ or dirty? • Ductwork: Leaks? Yes______ No______ Where? ________

• Duct broken or missing? Yes_______ No_______ Where? __________

• Tape damaged or missing? Yes______ No_______ Where?______

• When was the unit last serviced? • Less than one year • More than one year • Don’t know_______

Hot-Water Heater:

• Insulated? Yes______ No______ • Are the pipes insulated? Yes No______

Basement Ceiling:

• Insulated? Yes_______ No_______ What kind of insulation? _______ • How deep?

• Are the holes around heating vents filled in? Yes __ No_______ • With what? ____

• Is the filling good, fair or poor

Next: Plugging the Energy Leaks: The House: Introduction and Weatherstripping