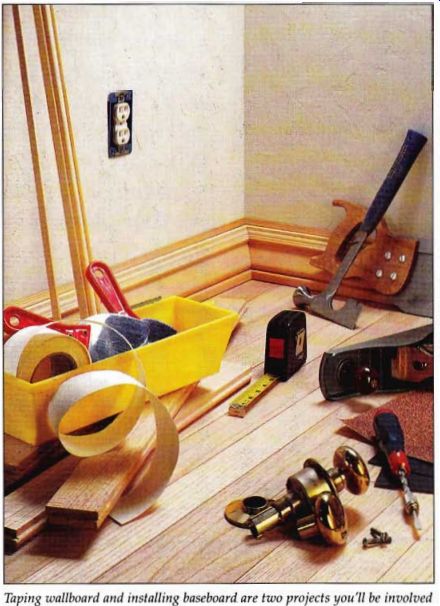

Carpentry tools

When you have completed the projects in this chapter putting up ceilings and walls; installing closets, cabinets, and shelves; and adding interior casings and trim-you will be ready to decorate and move into your finished home.

Before starting work on the interior, take a careful look around. Now is the time to make any changes. Try to imagine each room furnished, and foresee possible problems. Where will the bed go? Have you planned outlets for lamps beside it? Will the closet doors clear it? Is there enough storage space? Although you should have made all the decisions concerning the floor plan before you started to build, you may have had a change of heart, or your requirements may be different now.

Decide whether each room is the size and shape you want. Don’t change them too hastily-spaces are deceptive when defined only with framing-but even moving a nonbearing wall is not difficult at this stage.

Although there is still a lot of work and mess ahead of you, the excitement of seeing your new home take shape will spur you on.

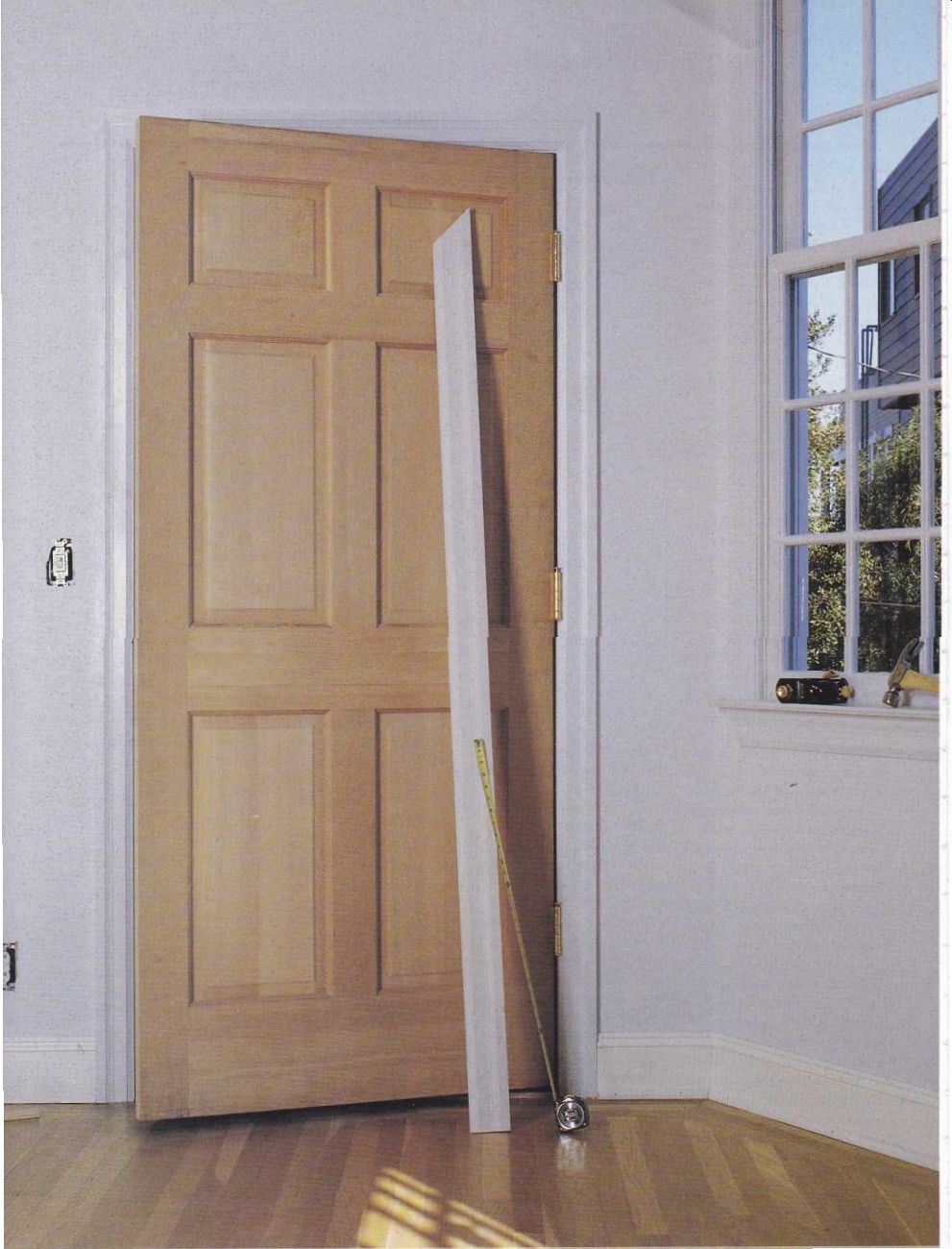

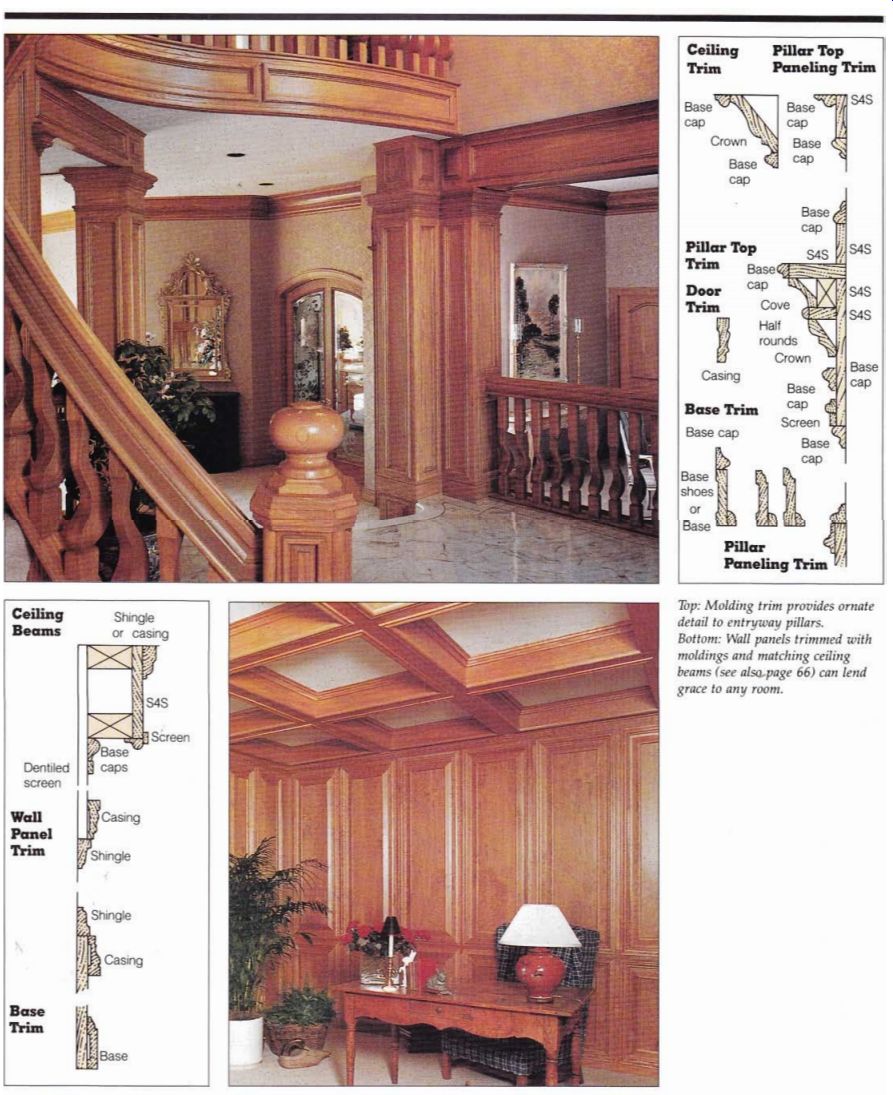

----------- Finely crafted trim details, such as gracious moldings and

small-paned windows, mark the attention of a careful, patient finish carpenter.

+++++++++++++++++

SEQUENCE OF ACTIVITIES

As with exterior finish carpentry, there are many materials and techniques you can choose from to finish the interior of your home. Now that the exterior is weatherproof, you can take a well-earned breather and make these decisions at your leisure.

Interior finish work can proceed once the heating, plumbing, wiring, and insulation have been installed.

As you reach each succeeding phase of a house-building project, you must pay more and more attention to detail. This is because the visibility of the work is greater. Your task, then, for this phase of the project is to bring to the job site the appropriate frame of mind and to proceed in the knowledge that you and others will be viewing your handiwork for a long time. This phase represents the culmination of all the skills and experience you have developed over the course of the project. By now you will have gained a certain measure of confidence that you can draw on to get the work done.

Where you choose to do each job and how you set up your work station will affect your efficiency and the quality of the end product. Before starting a given task, visualize the work to be done, the size and nature of the materials you will be handling, and the physical movements required. Once you grasp the whole picture, you can choreograph the activities efficiently.

Remember the underlying principle of all carpentry, which is especially important in the finishing phase: Take measurements twice and cut once. This means that before making any cut, you double check your measurement. It will undoubtedly save you time, money, and aggravation in the long run. Establish this habit at the beginning; you will soon understand why it pays.

Another technique essential to successful finish work is to install the materials so that they give the best appearance possible, even though there may be flaws or defects in the surrounding materials. Say, for instance, that when installing molding, you find that the walls are not square and you cannot correct this law completely. You may have to compensate by making cuts that are not perfectly true and joining pieces together in such a way as to camouflage the connection. This is best accomplished by imagining what the eye will perceive when the work is finished. It is perfectly valid and acceptable to compensate for laws; to do so skillfully marks your achievement as a finish carpenter.

Remember to get help when you need it. Holding up a long trim piece while trying to nail it in place is not only awkward but also potentially hazardous.

A second pair of hands can make the job proceed faster and more safely.

The tools you will need for each of the activities described in this chapter will be discussed in the appropriate sections. Refer to the chapter "Gaining the Skills" for tips on using them.

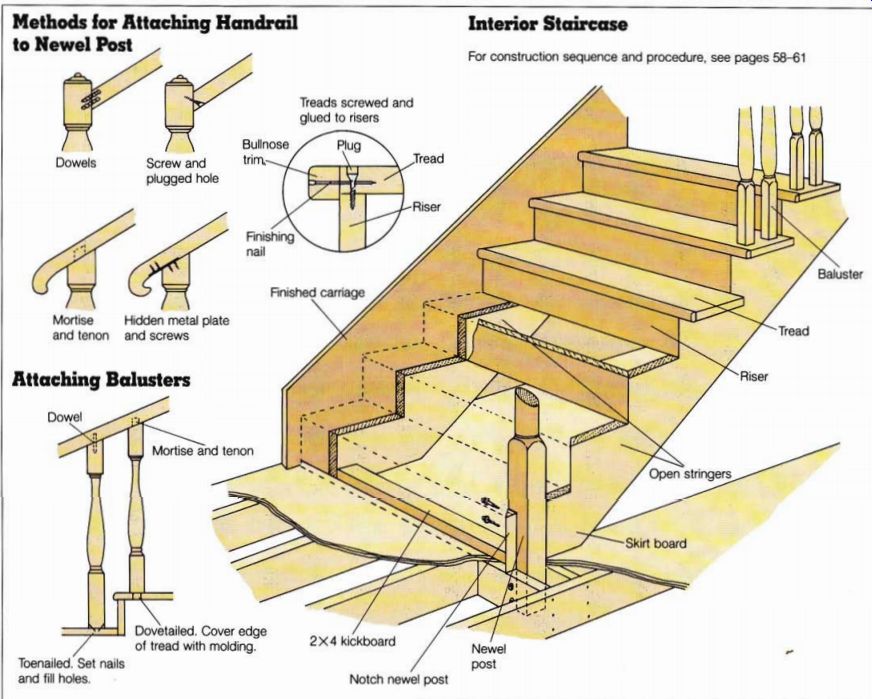

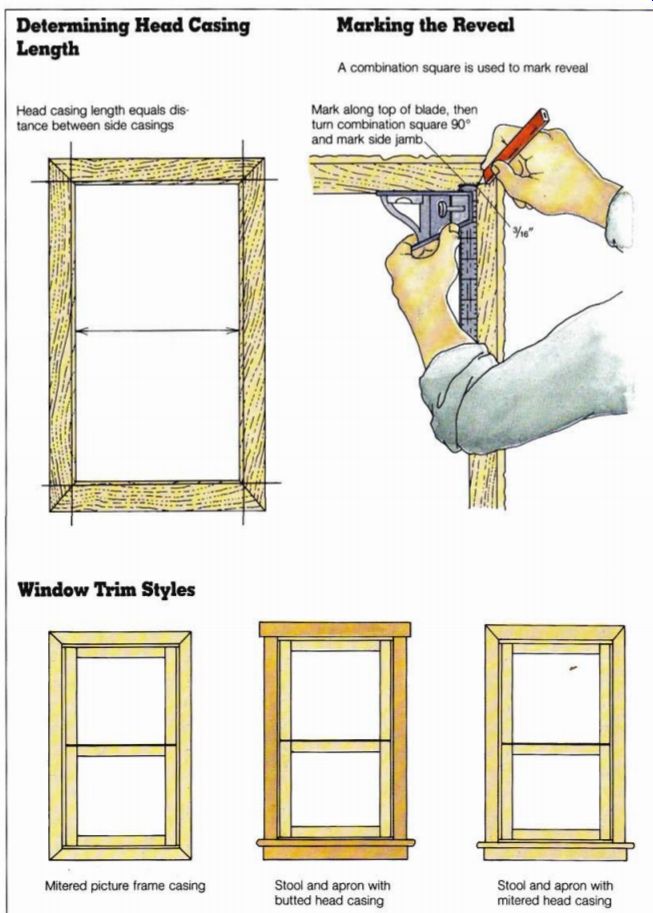

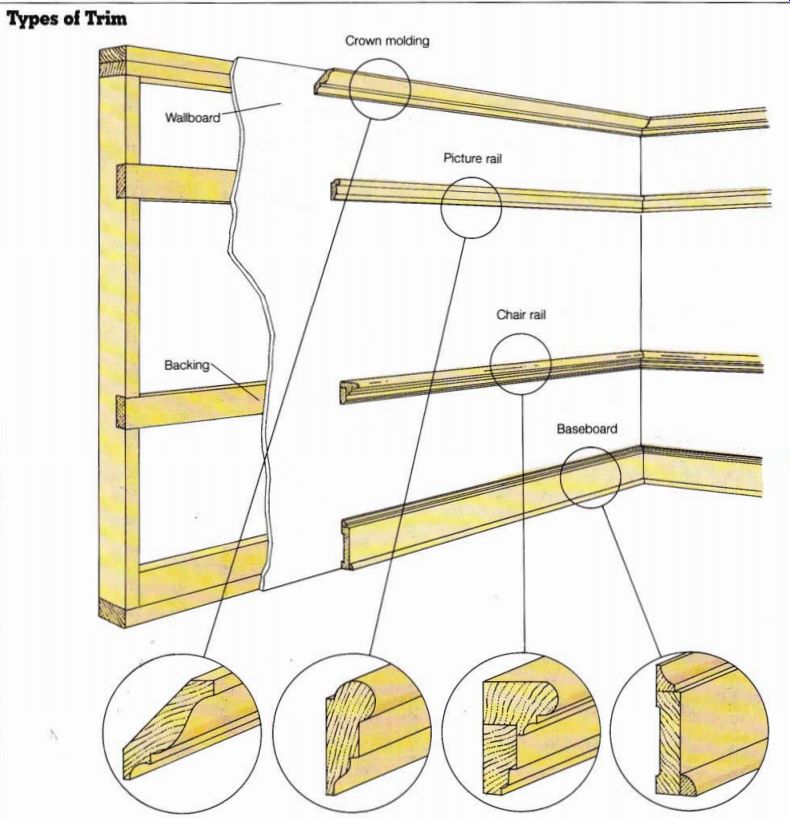

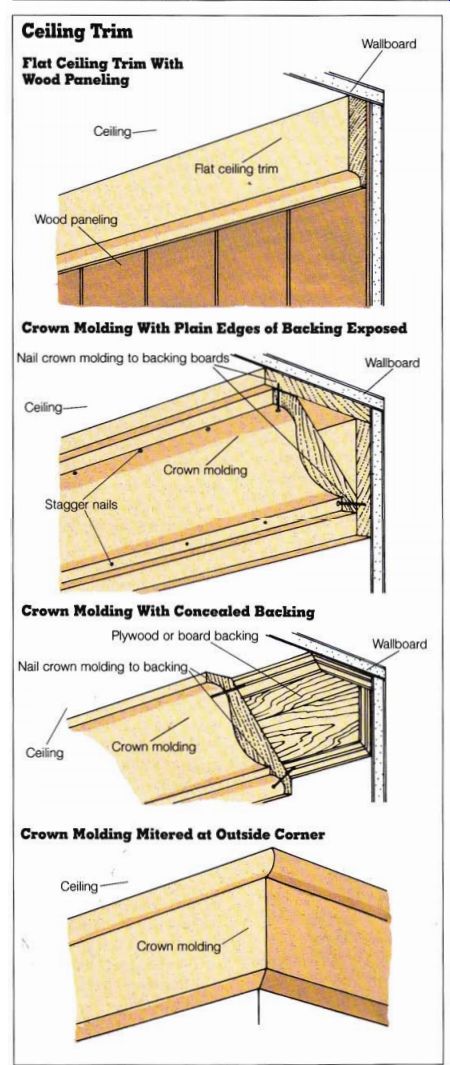

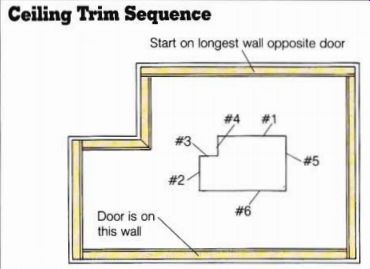

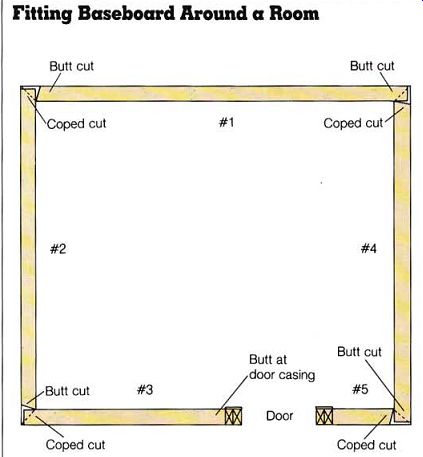

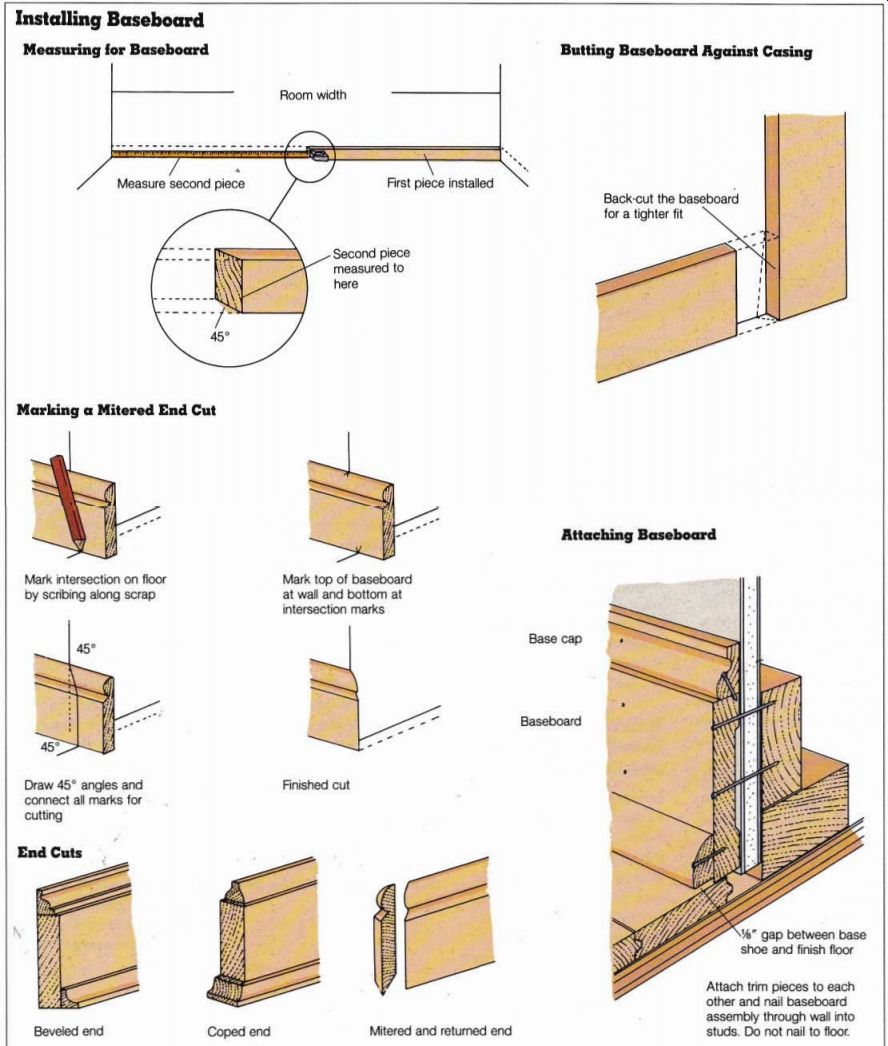

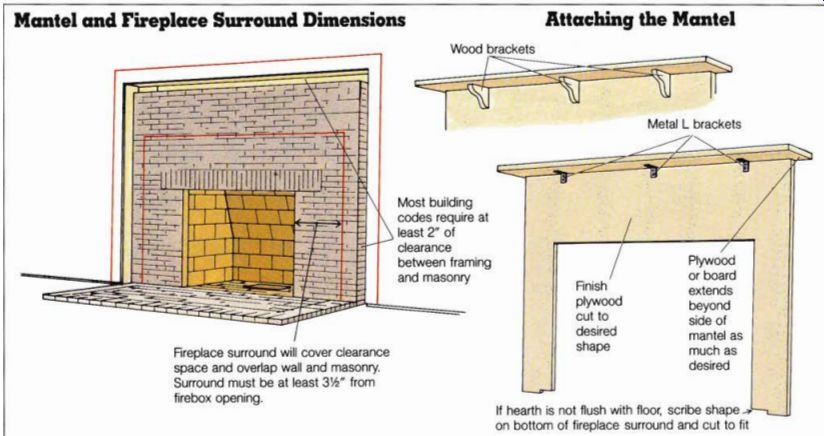

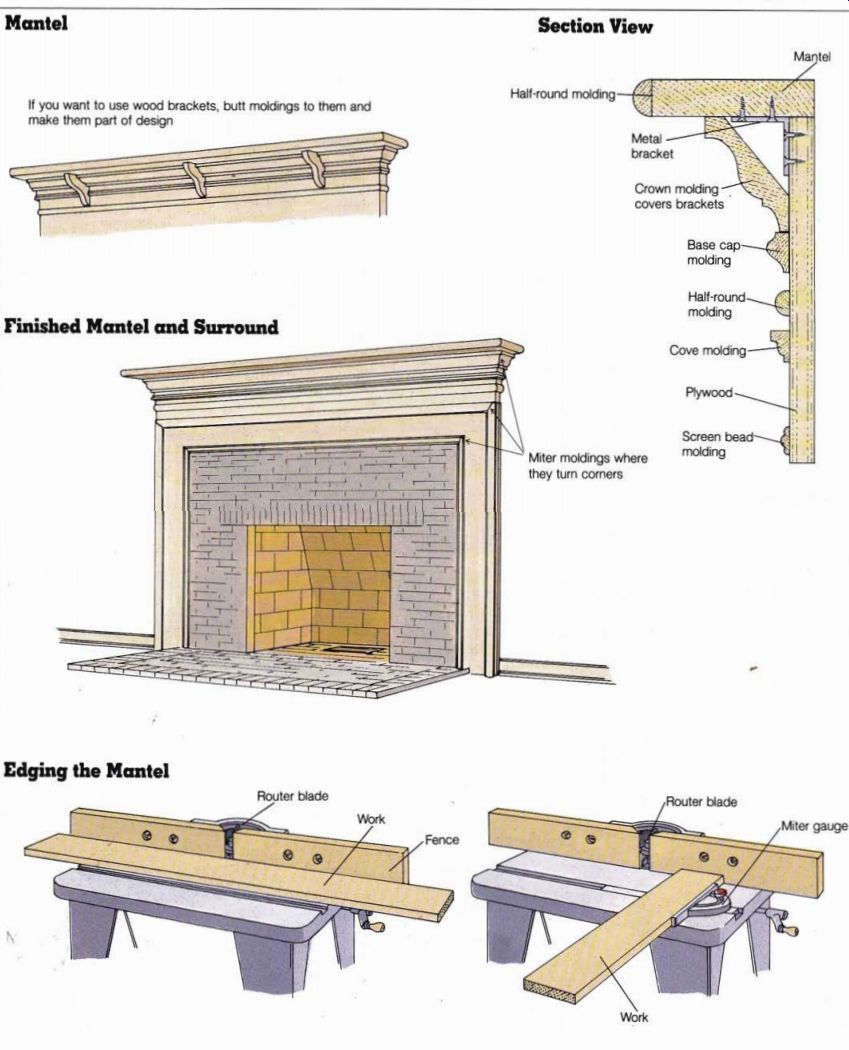

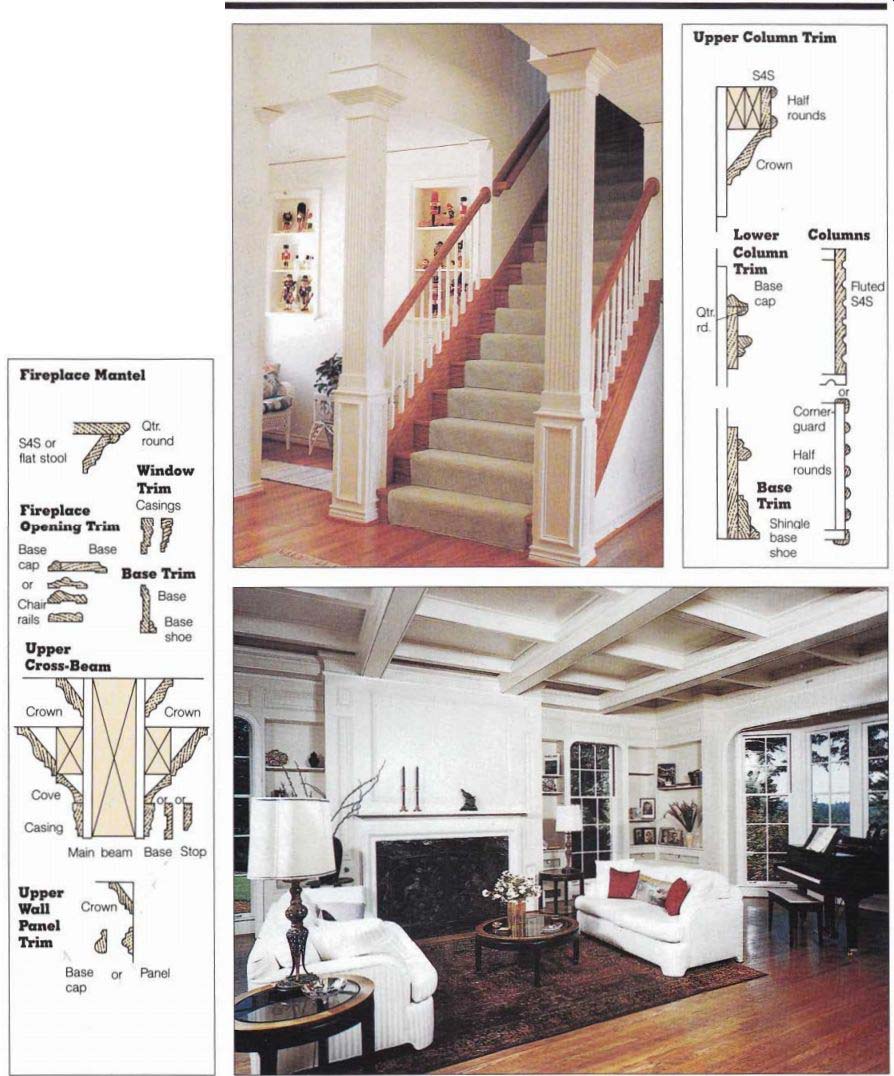

The general rule for interior finish carpentry is to work from the top down. Cover the ceilings first and then the walls. After that the usual order is to hang the cabinets, construct the interior stairs and railings, hang the shelves, in stall the door and window casings, put in the wainscoting, install the baseboards and other moldings, and finally build and install the fireplace mantel. In most instances, if you do these jobs out of order, you will have to do some of them twice.

Correct any laws before you start each activity. This is always advisable; often it is the only way to achieve a fine finish. The laws requiring remedy are discussed in the appropriate sections following.

It’s time to get started. Read each section carefully, follow the directions, and know that you have prepared yourself well for the jobs at hand.

---------- Taping wallboard and installing baseboard are two projects

you'll be involved in when finishing the interior of your home.

+++++++++++++

CEILINGS

The first task in interior finish carpentry is to install the ceiling material. Not only is it a good idea to get this awkward job over with, but it is always better to finish a room by starting at the top and working down.

From the Top Down

There are two main reasons for starting with the ceiling when finishing a room.

. You can get a tight fit between the ceiling and the walls, and later, between the walls and the floor.

. You should always try to in stall the most visible surfaces last, when they are least likely to be damaged. Dropping a hammer or stepping on spilled nails is almost guaranteed to leave marks on a newly surfaced floor unless it has been very carefully protected.

Lighting

Before you hang the finish ceiling, make all decisions regarding overhead lighting. If you plan to install either a flush mounted or a pendant fixture, attach an appropriate fixture support to the ceiling box. If your scheme includes recessed spotlights or floodlights, these must be installed before the ceiling is hung. In either case, mark and cut out holes in the ceiling panels before you attach them. Work carefully; although the edges of the holes will be hidden under a cover plate or trim piece, there is not much room for error.

Play It Safe

Wear safety goggles. It is un comfortable enough working above your head without running the risk of getting dust or shavings in your eyes. Wear a tool belt, too. Balancing tools on top of a ladder can be dangerous, and it is certainly a nuisance when they fall.

Scaffolding

When you're on a ladder, don’t try to save time by stretching beyond the area that you can easily reach. Coming down and repositioning the ladder takes a lot less time than waiting for broken bones to mend. If possible, work from scaffolding. You can rent small units that fold up, are adjustable, and have locking casters. If scaffolding is unavailable, erect a simple version by placing a board be tween two stepladders. Make certain that neither the ladders nor the board can slip.

--------------

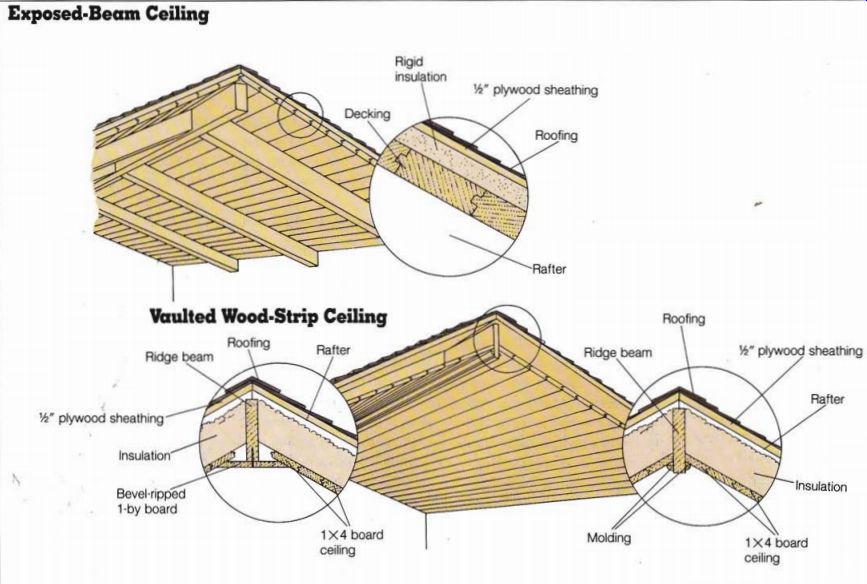

Exposed-Beam Ceiling Rigid insulation W plywood sheathing

Roofing Vaulted Wood-Strip Ceiling Roofing Ridge beam X Ma'

3/8" plywood sheathing' Insulation' Bevel-ripped 1-by board 1X4 board ceiling Rafter Roofing Molding 1/4" plywood sheathing Rafter Insulation 1X4 board ceiling

------------------

Exposed-Beam Ceiling

In some homes the decking for the roof is also the ceiling for the room below; the rafters and joists (or beams) are exposed from within. With this type of ceiling, use rigid insulation and 3/8-inch plywood sheathing on top of the decking, and then apply the finish roof.

Use decking that is 2 inches thick (nominally). Consider using tongue-and-groove soft wood flooring in a C or D grade for the decking. It is available up to 1 3/16 inches thick and 1 3/8 to 5 7/16 inches wide.

Start the layout for the decking on the upper edge of the rafters, so that the horizontal decking joints at the top of the ridge are parallel to the ridge beam. Starting at the ridge measure down the rafters at each end of the roof the distance necessary to completely cover the roof, and make a mark at this point. Stretch a chalk line from end rafter to end rafter at this mark. Snap the line across all the rafters.

This is the true starting point for installing the decking.

Align the first piece of decking with the snapped line.

Facenail it with two 16-penny (16d) hot-dipped galvanized nails at each rafter. Complete the first course of decking in the same way. Be sure to center the joints over the rafters. Proceed with the next course of decking, this time using one face nail and one blind nail driven down diagonally through the tongue of the decking into the rafter. This drives the groove of the piece of decking tightly against the tongue of the previous piece, giving it a finished look.

As you install the succeeding courses of decking, take periodic measurements to make sure that they are still parallel to the ridge. You will probably find that the distance is increasing at one or more of the rafters. If this happens, al low the seams to open slightly over the next few courses where the distance is shortest.

Do this until you regain a line parallel to the ridge.

You will undoubtedly fall into a comfortable routine, checking every four or five courses to ensure consistency.

Try to keep the seams as far as possible from the walls and ridge, to minimize the effect of nonparallel lines. This may require that the starter piece be ripped to the dimension that allows for the maximum distance between wall and seam.

Vaulted Wood-Strip Ceiling

With this type of ceiling, the wood strips are nailed to the bottom of the rafters, unless lo cal codes require a layer of wall board under the rafters. Batt insulation can be installed be tween the strips and the roof sheathing. To achieve a tight fit, tongue-and-groove strips are better than straight-cut boards.

A wood-strip ceiling is generally installed with the strips running horizontally. Place the first course (groove side down) so that the bottom edge butts up to the wall. As with the installation of roof decking described above, the starter course of wood strip should be positioned to allow for parallel seam lines as the ceiling reaches the ridge beam. You may have to rip the starter piece at an angle to achieve this result, because the wall and the ridge beam may not be parallel.

Plan carefully so that the last board you install against the ridge is as close to full width as possible.

Nail the starter piece in place and continue to the peak.

The best appearance is achieved when wood-strip ceiling material is blind-nailed, and no face nailing is done.

This means that only one nail is used for each course of wood strip, but this is ordinarily sufficient for 1-by material. Measure frequently and make small adjustments so that the final course is parallel to the ridge beam. Place insulation between the rafters as you proceed. A ridge beam protruding into the room can be edged with strips of molding, or it can serve as a nailing board for a piece of bevel-ripped 1-by stock.

When 1-by material is used, the rafters should be spaced no wider than 24 inches on center for best appearance.

Crisscrossed Beam Ceiling

Ornate beamed ceilings can be created using decorative trim installed beneath a standard ceiling of wallboard or wood paneling. Before starting the actual installation, experiment with various combinations of moldings and dimensioned lumber to create a pleasing de sign. Work out a pattern that attaches easily to standard framing lumber (2 by 2, 2 by 4, and 4 by 4 are the most commonly used). See pages 108 and 109 for examples.

The first step is to attach a grid of framing members to the ceiling to support the pieces of decorative molding. The size of the framing members can vary depending on the scale of the room. For smaller rooms use 2 by 2s or 2 by 4s. Run the first pieces full length across the ceiling, perpendicular to the ceiling joists and spaced 3 to 4 feet apart. Snap chalk lines on the ceiling to keep the framing straight. Secure the framing members where they intersect each ceiling joist with a self tapping wallboard screw or a lag screw. The screw should penetrate the ceiling joist at least 1 inch. Countersink the heads of the lag screws.

When all the full-length members are in place, cut and install identical framing pieces between them to create a criss cross grid. Apply a bead of construction adhesive to the top of each crosspiece. Then hold it in place against the ceiling and either toenail or screw each end to the full-length framing member.

For larger rooms with long spans or ones that require massive beams, you .can make lightweight hollow box beams out of 2 by 4s and plywood.

Attach the upper 2 by 4 members first, as described above.

Then, to complete the beams and make them deeper, fabricate continuous U-shaped channels the same length as each ceiling member, using 2 by 4s with plywood glued and nailed to the sides. Nail each channel to the corresponding grid member on the ceiling.

Once the framework grid is in place, attach the decorative trim pieces to the sides and bottom of the beams.

+++++++++++++++++++

Wallboard Ceilings and Walls

---

The most widely used covering for interior walls and ceilings is wallboard. It has almost entirely replaced lath and plaster in general residential applications because it has the properties of plaster and many other advantages as well.

Properties of Wallboard:

You may recognize wallboard by one of its other names […]

•The sheet form enables you to obtain flat wall surfaces with out acquiring the specialized skills of a plasterer.

•The gypsum compound in wallboard retains 20 percent water, which makes the wall board tire resistant.

• Manufactured sizes confirm to standard wall heights.

Selecting Wallboard.

Wallboard usually comes in 4 by 8 panels. although longer panels are sometimes avail. The standard thicknesses are V. inch, } inch, ', inch, and ¾ inch.

•The ½-inch sheet is the standard panel for residential construction. It combines ease of handling with good impact resistance. A 4 by S sheet of ½-inch wallboard weighs 58 pounds-light enough (or one person Lo handle.

The ' sheet is often used for tni ceilings where the truss spacing is 24 inches on center. It is also used on 'fl mon walls between a house and an attached garage, for example, for greater fire protection.

•The '.-inch sheet is used primarily for resurfacing t watts. I3ccausi it has little impact resistance, it must be solidly supported.

•The 0.5-inch sheet can be used for resurfacing, but it is more often hung in a double layer to make ¾-inch nails. The sound insulating properties of a double panel make it a good choice for recreation moms.

• Special 0.5-inch wallboard is manufactured for use in high-humidity area such as bathrooms and laundry rooms. This type ol wallboard is identified by the light green or blue cover paper, which is moisture resistant. In addition. the core is made of a moisture-resistant gypsum compound.

Insulating wallboard is similar to regular wallboard except that it has a foil coating one side. it' obtain the benefit, you must leave a ' air space between the foil and any other insulation. The foil also acts as a vapor barrier.

---- Correcting; Framing Flaw.

------------

Wallboard is available with a decorative surface laminated to one side. This surface, usually vinyl, comes in colors, patterns, and simulated wood grain or marble. Consider this for a child's room, where it is often necessary to remove a future Picasso’s handiwork from the walls.

Be aware that installing wallboard, although not difficult, is extremely messy, arduous, and time-consuming for the amateur. If the budget al lows, call in the pros. You will be amazed at how quickly and seemingly easily they get the job done.

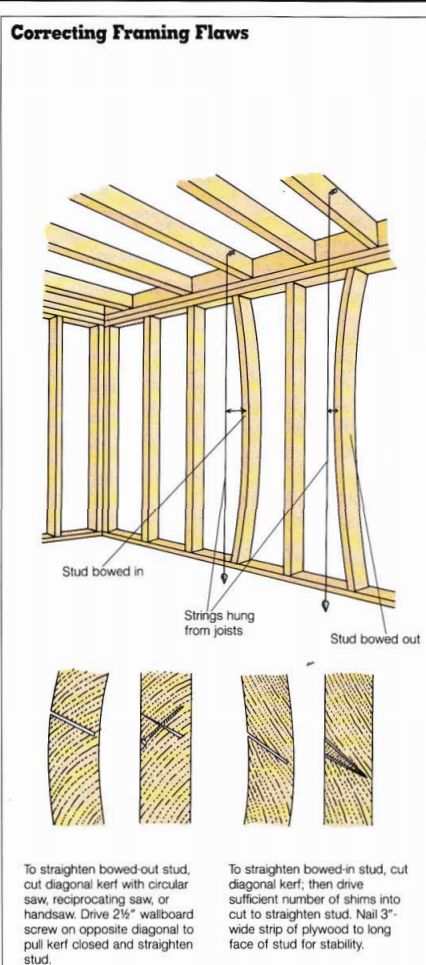

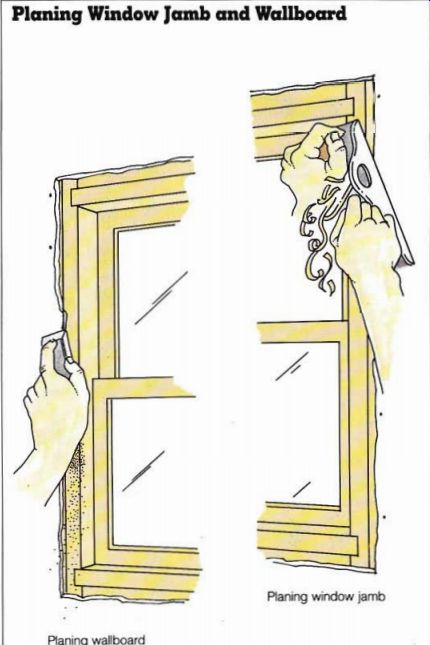

Preparing for Installation

Hanging wallboard is much easier if the joists and studs are even and square. Check with a string nailed to the member in question. If you find studs that bulge inward or outward more than about 3/8 inch, correct the problem before proceeding. If a stud is bulging out, straighten it by making a diagonal hand saw cut about three quarters of the way through the stud; then drive a screw through the cut to squeeze it together. A bulging stud may also be straightened by shaving or planing. If a stud is curved inward, make the same cut; drive in enough shims to straighten the stud; then nail a 3-inch piece of plywood scrap alongside the stud for stability. See illustration on page 67.

Other flaws and oversights should be corrected before the wallboard is hung. Check to see that all electrical outlet boxes are extended away from the stud or ceiling joist at the proper distance to receive the wallboard. Finally, be sure to provide a backing wherever the wallboard is to be fastened.

To prepare for installation remove any moldings attached to the window frames. Bring the wallboard into the room and stack it in the middle of the floor. If you lean it against a wall, you run the risk of cracking or warping the panels and damaging the edges.

Studs, plumbing, and electrical conduits determine where the wallboard can be nailed. You want to hit the studs, not the conduits or the plumbing. Before putting up the wallboard, remember to at tach protection plates to studs drilled for plumbing and wiring; nails won’t penetrate the protection plates.

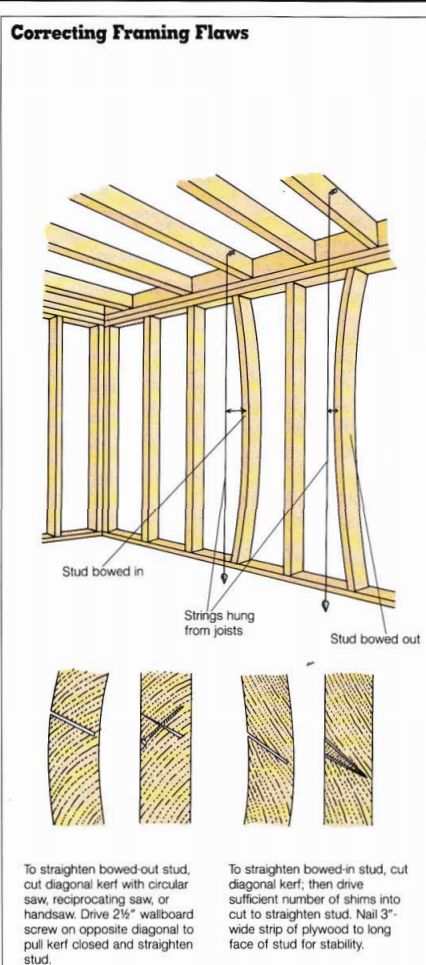

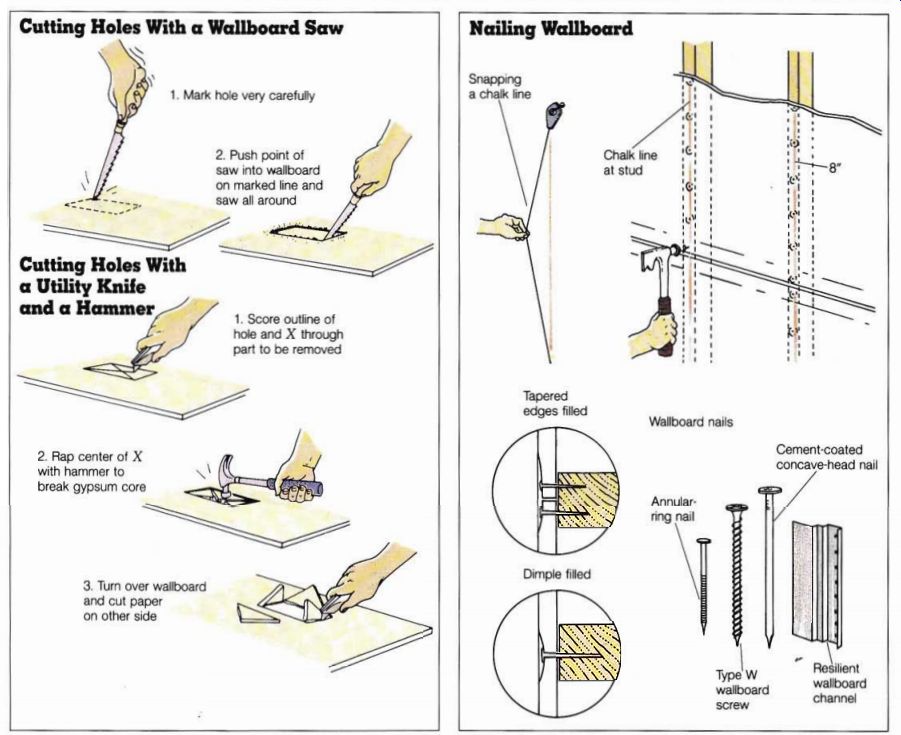

So you'll know where to nail the ceiling wallboard once it covers the joists, mark the location of the joists on the plates. When the ceiling wall board is in place, mark on it the location of the studs, so you'll know where to nail the wall board for the walls. See illustration. Tack the wallboard adjacent to the joist and stud marks. Then snap a chalk line as a guide for nailing.

When soundproofing is required between living levels in a multistory dwelling, you can install a sheet-metal strip, called resilient channel, on the ceiling of the lower level, to which a second layer of wall board is attached. This reduces the sound transmission be tween levels. See illustration on page 70, right.

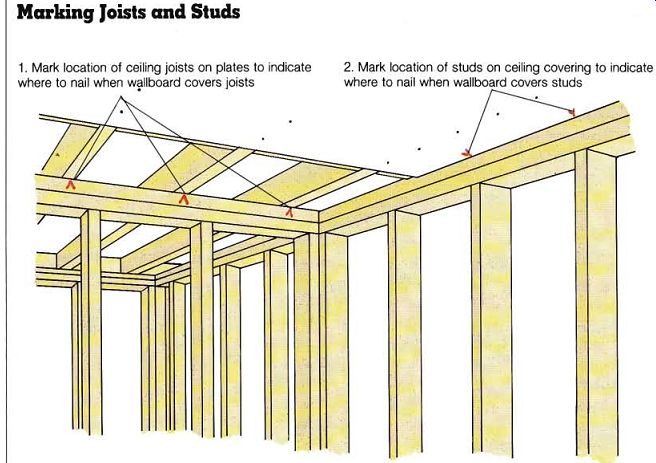

----------- Measuring and Laying Out Wallboard

When more than one measurement is involved in a sequence, take progressive readings with a steel tape in one position, rather than moving the tape after each reading. This reduces cumulative error.

To take progressive readings lay a panel of wallboard on sawhorses in the same position as that in which it will be in stalled. Touch the tip of the tape measure to a ceiling-wall corner or to the edge of the adjacent piece of wallboard. Extend the tape to the first edge of any cutout that you come to, such as an electrical outlet box, a recessed light fixture, a window or door frame, or a wall opening. Record this dimension on a scrap of wall board on which you have first drawn the entire schematic of cutouts for this panel. Then ex tend the tape to the other side of the cutout and record this dimension on the schematic.

Measure any other cutouts necessary to complete the panel in one direction. Then take perpendicular measurements:

Touch the tip of the tape to the wall (or to the ceiling if you’re measuring a wall panel) or the adjacent piece of wallboard, then follow the same procedure. See illustration at right.

Make the actual cutouts about 0.25 inch larger all around than the dimensions on the schematic. This makes it easier to install the panel. The exception is cutouts for electrical boxes, which should be within H inch or less of the actual size of the box.

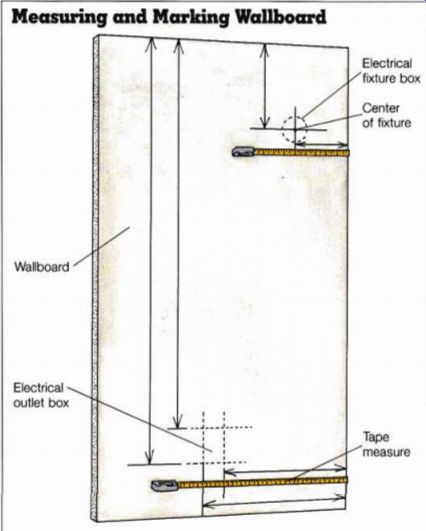

Cutting Wallboard

Cut sheets of wallboard by scoring the top (finish) surface with a utility knife. Draw a line with a pencil first or snap a chalk line on the face of the sheet. Use a T square (the 4-foot size is the handiest) to ensure that the line is straight. Now bend the board backward. If it does not break easily, bend it over a 2 by 4 or use your knee.

After the wallboard snaps, cut the back surface with the utility knife. If the break is not clean and gypsum protrudes beyond the edge of the paper, use a rasp to remove the excess.

Use a wallboard saw to cut holes or irregular shapes in the panels. This pointed saw, which has a sturdy 6-inch blade and five teeth per inch, can poke right through a panel to start a cut, and the coarse teeth will not clog up. See illustration below.

----- Measuring and Marking Wallboard

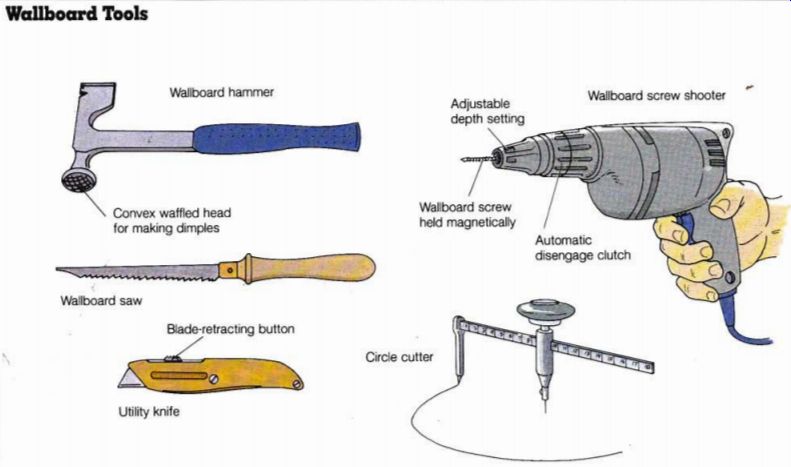

---------- Wallboard Tools Wallboard hammer Utility knife Adjustable

depth setting Wallboard screw shooter Wallboard screw held magnetically

Automatic disengage clutch Convex waffled head for making dimples Circle cutter

--------------

-------- Nailing Wallboard ; Snapping a chalk line Tapered edges

filled Wallboard nails Cement-coated concave-head nail Annular ring nail

Type Wallboard screw wallboard channel Dimple tilled

----------------

An adjustable compass-like device called a circle cutter scores accurate circles. It has a 3/8-inch pin at the point.

Push the pin through the front of the wallboard and score the edge of the circle. Use the same hole to score another circle on the back of the wallboard. Punch out the circle. See illustration on page 69, bottom.

Be sure to measure each panel carefully. Plot the cuts in pencil on the surface of the board and recheck the measurements before you break the surface.

If you have some scrap wall board to practice on, try the method that the pros use to make rectangular cuts-it is fast once you get the knack. Pencil the cuts onto the board and score them with a utility knife as de scribed above. Score an X through the area to be cut and tap the center with a hammer.

This loosens four wedge-shaped pieces, which fall free when you cut the back cover paper. See illustration above left.

Attaching Wallboard

Wallboard may be nailed, screwed, or glued to the studs.

Whichever method you use, the panels should fit snugly against each other. Do not economize by using cut pieces of wallboard. The material is cheap, and the joints are not as neat when neither butted panel has a tapered edge.

Nailing Wallboard

The most common method of attaching wallboard is nailing.

Use the annular-ring nails de signed especially for this purpose; the rings should prevent the nails from popping out. See illustration above right. Choose a nail long enough to penetrate the framing 3/8 inch to 1 inch after passing through the wallboard.

Let the framing reach its stabilized moisture content before nailing into it. Wood shrinks as it dries, which makes the nails pop out. If possible, close the doors and windows and keep the room at about 72° F for at least four days, preferably two weeks, before you install the wallboard.

When attaching the ceiling panels, space the nails 7 inches apart along each joist and no less than % inch from the edge of a panel. Attach the wall panels with nails spaced 8 inches apart along each stud. For a handy nail-spacing guide, affix pieces of tape to your hammer handle 7 inches and 8 inches from the head.

Be careful not to break the cover paper of the wallboard when you drive in the nails.

Using a special wallboard hammer will reduce the risk of damaging the surface. The checked face of the hammerhead is bell shaped to seat the nail head below the surface. See illustration on page 69, bottom.

Screwing Wallboard

Wallboard can also be attached with screws. This method is becoming popular; however, you will need a drill with a clutch, which costs between $90 and $130. The special bit can be bought at most home improvement centers for about $1. For small jobs it may be more economical to rent the tool, but be realistic about how long the job will take.

The 1.25-inch Type W screws are stronger than nails. See illustration on page 70, right.

You can space them up to 12 inches apart on the ceiling and up to 16 inches apart on a wall, but not closer than 3/8 inch to the edge of the panel. The screws are driven by a Phillips screwdriver bit in a drill with an automatic disengage, which activates just as you counter sink the screw head.

Unlike nails, screws do not require a fine touch. Just keep an even, solid pressure on the dill. Don’t let the bit jump the screw slots or you will have a very messy hole.

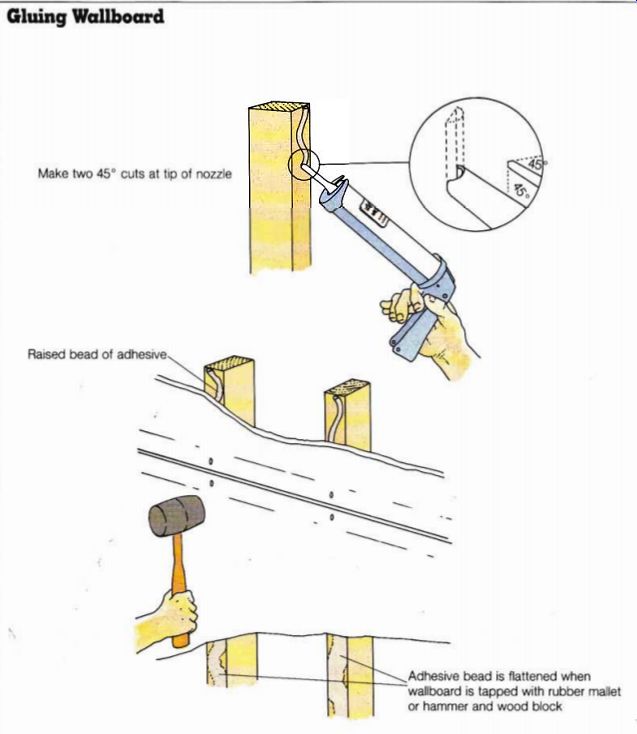

----- Gluing Wallboard

Gluing Wallboard

Wallboard held to the studs by adhesive makes a stronger wall and one that absorbs more sound. Using adhesive also eliminates nail holes-and the job of filling them. Pre-decorated panels look better glued, even though matching nails are usually available.

This method is well suited to small jobs, on which you can use 1-quart cartridges of adhesive. Large jobs are done with a refillable applicator and adhesive in 5-gallon cans.

Hold the applicator at a 45-degree angle to the framing member and apply a 3/8-inch wide bead of adhesive. Use a zigzag pattern on members where two panels meet. See illustration.

After you have applied the adhesive, lift the panel into position and press it firmly against the beads of glue. Nail or screw the outer edges only or tap with a rubber mallet.

To ensure contact and to spread the adhesive, hold a 2 by 4 protection block against the surface and strike the glue lines with a hammer.

On pre-decorated panels overlap the extra surface material or attach matching battens over the joints.

-----

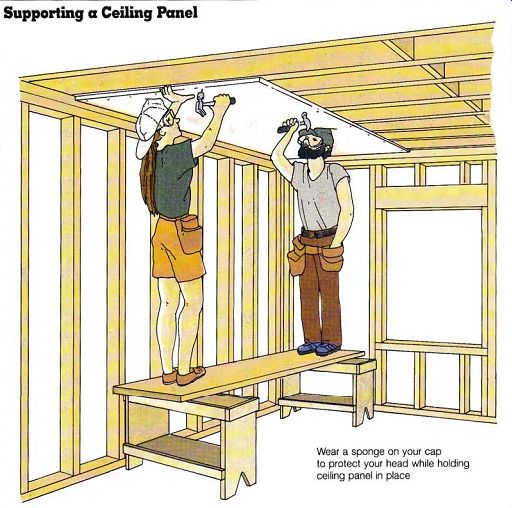

Installing the Ceiling

It is best to have help when you install the ceiling (see illustration). However, you can do it alone if necessary, using a T-brace or a rented wallboard jack. A T-brace is simply a long 2 by 4 with a crosspiece nailed at the top. The long upright must be slightly longer than the floor-to-ceiling distance so that the T-brace can be jammed up under a piece of wallboard to hold one end in position while you nail the other. To cushion your head for holding wallboard against the ceiling as you nail it, wear a hard hat or a cap with a sponge under it.

A jack is much easier to use.

You place a sheet of wallboard on it, then crank the jack so that it lifts the wallboard up to the ceiling and holds it there.

The jack is on wheels so that you can roll it around to position the wallboard perfectly.

Start by positioning a full panel in one corner. Attach the panel to the joists, using the method of your choice. Cut the last panel in each row 0.25 inch short, to provide clearance at the end. If the walls are going to be finished with wall board, nail no closer than 7 inches to the edge of a ceiling panel; the butting panel will tighten the joint. Complete the first row, placing the panels end to end. Position the joints on the joists, as close as possible to the center of the joists. A dozen or so fasteners will hold each panel in place until the remaining ceiling panels are in stalled, at which time you can finish fastening all of them.

Cut the first panel of the next row in half, since staggering the joints results in a finer job.

When you come to a panel that needs a cutout-for a light fixture or a trapdoor to the at tic, for example-transfer the measurements from the ceiling to the wallboard before raising the panel. (See Measuring and Laying Out Wallboard, page 68.) Pencil the cut lines onto the face of the panel so that the opening will be no larger than necessary. Recheck your measurements before you cut.

If you are covering the walls with wallboard, put these panels up before taping and filling the ceiling.

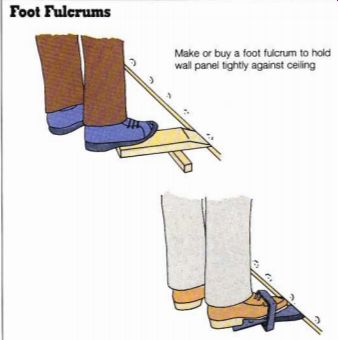

-- Foot Fulcrums---- Make or buy a foot fulcrum to hold wall panel

tightly against ceiling

Installing the Walls

The materials and techniques used to cover walls are basically the same as those used for ceilings. Since the studs run vertically, the preferred position for the panels is horizontal. It is acceptable-and in fact faster to run them vertically, but this way the joints are more likely to show as the structure settles.

Fit each panel snugly against the ceiling; use wedges or a foot fulcrum (see illustration) to help you to get a tight fit. A gap of 0.5 inch to 3/8 inch at the bottom is acceptable-it will be covered later by the baseboard.

Starting in one corner slide the panel up against the ceiling and attach it with nails, screws, or glue, as described on pages 70 to 72. If you're placing the panels horizontally, complete the upper row around the room. Cut out openings as accurately as you can; plates will cover the holes you make for electrical outlets and switches, but they don’t allow much room for error. Openings for doors and windows are less critical, because the gaps will be covered by molding. Avoid joints at the corners of doors and windows, since cracks are more likely to appear at these locations.

The second of the two panels forming an inside corner butts up to and holds the first panel against the framing. For this reason you don‘t need to nail or screw the first panel along the butted edge. The panels forming an outside corner lap must be capped with a metal corner beading to protect the edge. The beading is covered later with joint compound.

Taping and Filling the Joints

Whether the wallboard is attached with nails, screws, or glue, you have to hide the joints and fasteners. Vinyl covered pre-decorated wall board may have a flap to cover the joint, but standard wall board must be taped and filled, a process sometimes referred to as mudding.

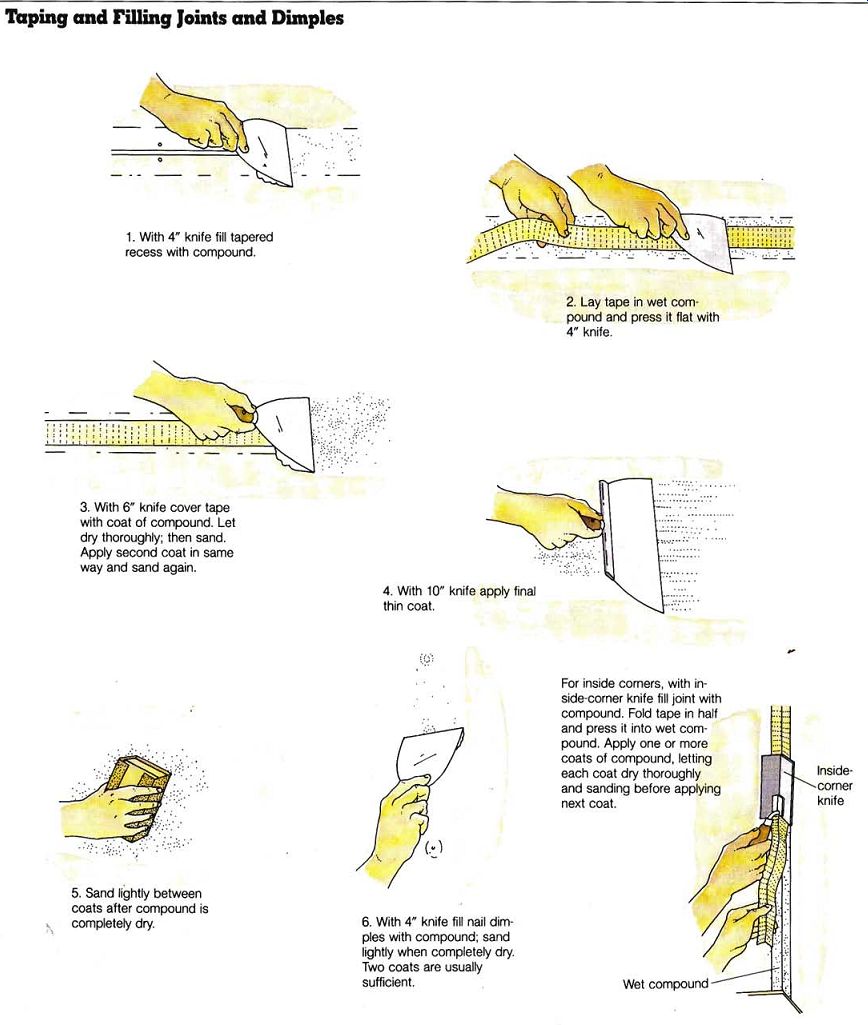

You need 4-inch, 6-inch, and 10-inch putty knives, a corner knife, paper tape, and joint compound. You can buy powder and mix your own joint compound following the manufacturer’s directions, or buy it premixed in containers holding up to 5 gallons. If you are using a large container of compound, scoop a small amount into a tray and work from this. Clean out the tray often, because dust and dried-out compound make it difficult to get a smooth surface.

Start by spreading a quantity of compound into a joint with a 4-inch knife. Lay the tape on the wet compound and embed it smoothly. (Some people find that wetting the tape before pressing it into place makes application easier.) Apply more joint compound over the tape with the 6-inch knife, feathering the edges. Re peat this procedure for all the joints. Fill all nail dimples you don’t need tape here. Allow the compound to dry; then sand lightly before applying the next coat. See illustration on page 74.

An alternative to paper tape is a 2-inch-wide strip of fiber glass mesh that has a light adhesive on one side. This strip can be applied to the joint prior to mudding; the joint com pound penetrates through the openings in the mesh to the surface of the wallboard, speeding up the drying process.

Apply a second, wider coat with a 6-inch knife. Feather the edges, getting them as smooth as you can, and sand lightly when dry. (You can get a good finish and make less mess by smoothing the compound with a damp sponge.) Two coats are sufficient if you are going to apply texture compound. If you are going to paint or paper the walls or if you require a smooth surface for some other reason, apply a third coat with a 10-inch knife.

Finish inside corners and wall-ceiling joints in the same way. Apply the compound to the corner, smoothing it with a corner knife. Fold sections of tape lengthwise, place them on the wet compound, and use the corner knife to press them into place. Apply another coat over the tape and smooth it with the knife. Let it dry, sand lightly, and then apply a second coat.

On outside corners the metal beading takes the place of tape. Apply two or more coats of compound, letting it dry and sanding between coats.

Note: There are many ways to texture wallboard to make it look like plaster, but they all entail applying compound over the entire surface with a sponge, roller, or trowel. Experiment on scraps before doing this, or call in a wall board professional.

------------

+++++++++++++++++++++

WALL PANELING

Even if you don't use wood wallcoverings throughout the house, there are rooms that look particularly good decorated this way-the den or library, for example. A wide selection of panels is available; some are routed to look like individual boards.

Sheet Paneling This type of paneling is actually 0.25-inch plywood with a surface veneer in a selection of hardwoods, softwoods, textures, solids, simulated marble, and brick-the choice and the price range are large. You can even get wallpaper veneer over a Vi-inch plywood backing.

The 4 by 8 sheet is standard, but 9-foot and 10-foot lengths are also available. The sheets should always be applied vertically to avoid unsightly joints, so use the long ones if you have high ceilings.

Paneling can be installed over studs and over almost any existing wall surface, even concrete.

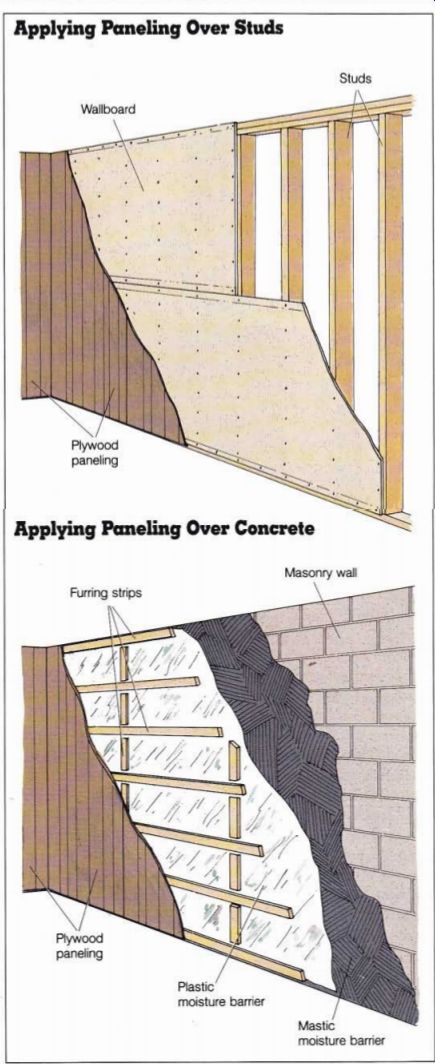

--------- Applying Paneling Over Studs

Plywood paneling

Applying Paneling Over Concrete Masonry wall Furring strips Studs Wallboard Plywood paneling moisture barrier moisture barrier

----------------

Over Studs

You can make the wall more solid and increase sound insulation by first covering the studs with 3/8-inch or 0.5-inch wallboard. See illustration.

There is no need to tape and ill, but you should stagger the wallboard and paneling joints.

Over Concrete or Concrete Block

Apply a coat of asphalt mastic (with or without plastic film over it) as a vapor barrier. Using a nailing gun ( see page 41) or hand-driven concrete nails, attach horizontal 1 by 2 furring strips every 16 inches. Attach vertical furring blocks between the horizontal strips at 48-inch intervals. Lay out the paneling so that the joints fall over these vertical blocks.

Once the support system is in place, attach the paneling with either nails or adhesive.

You can buy nails with heads to match the color of the paneling or the darker grooves. You can also use finishing nails and cover the heads with a special putty available in a convenient crayon-like stick.

Adhesives come in easy-to use cartridges. Adhesives are not all the same; follow the manufacturer’s instructions.

You must cut, it, and mark the exact position of each panel be fore you apply the adhesive.

Once the glue is on, it's too late to make adjustments.

Installing Sheet Paneling

When you use a circular power saw to cut paneling, you must cut with the face of the panel down so that any splintering occurs on the backside. A ply wood blade, which is designed to reduce splintering, makes for a neater job. If you use a hand saw or a table saw, be sure to cut the paneling face up.

Start by placing a full sheet of paneling in one corner and continue around the room.

Make sure that the first panel is plumb-if it is not, the entire installation will be crooked.

Gaps at the top and bottom can be covered by molding. Mark cutouts as you come to them.

Check your measurements and then cut, using a compass saw or a saber saw.

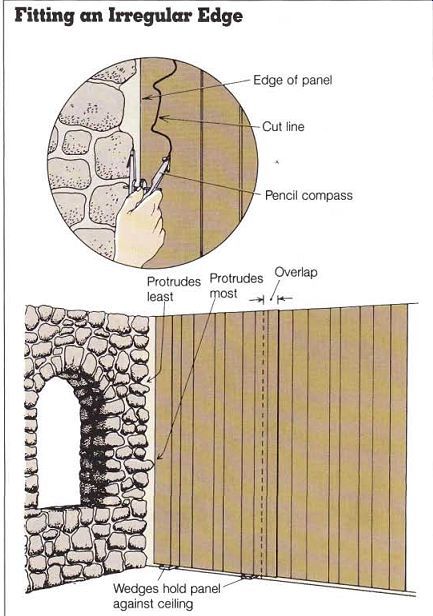

Irregular shapes can be traced directly onto the panel with a compass and pencil.

Place the panel against the irregular surface. Adjust the compass so that the span equals the amount that this panel overlaps the one next to it. If this is a first panel, butt it against the point that protrudes the most and set the compass for the distance between the edge of the panel and the point that protrudes the least. For the final panel, set the compass to the amount of overlap. In either case, mark the panel and cut with a saber saw or a com pass saw. See illustration.

Board Paneling

A more traditional way to obtain wood-finished walls is to cover them with paneling boards. These come in a variety of species, grades, and mill pat terns, with softwoods dominating the list. If you want wormy chestnut or cherry, consider laminated veneer panels rather than board paneling; hardwood boards are very expensive. Paneling boards are commonly available in 4-inch to 12-inch widths and with tongue-and groove or straight-cut sides.

Board paneling is usually applied vertically. First, cover the studs with wallboard. Then attach 1 by 2 furring strips horizontally, nailing them to the studs. If you are surfacing a smoothly sheathed wall, you can glue the boards with a panel adhesive. In this case, fur ring strips will not be needed.

With tongue-and-groove boards, drive 6d finishing nails into the V at the base of the tongue at a 45-degree angle and set the heads. See illustration on page 77. The next board clips over the tongue and covers the nail holes.

To keep from ending with a piece that is conspicuously narrower than the rest, you can work back from each corner with whole boards. A narrow board above a door or at a window will be barely notice able. Keep in mind that board paneling plus furring strips adds up to a thickness at least 1 1/4 inches greater than that of standard wallcoverings. Use thicker door frames or add square molding to build up the edge of standard frames.

Board-paneled walls can be finished in a number of ways.

Varnish, shellac, stain, paint, bleach, and antiquing (paint applied and then partially rubbed off with a rag) are some of the options.

------- Fitting on Irregular Edge Pencil compass Protrudes

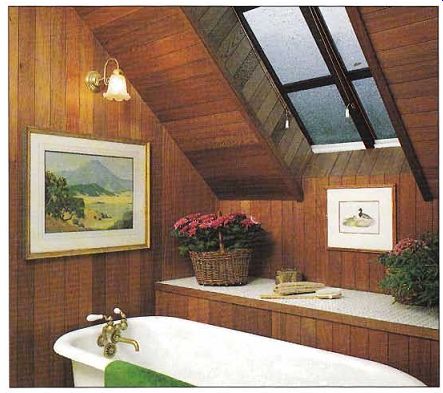

------------- Redwood board paneling covers the walls, ceiling, and

skylight well of this room. The tongue-and-groove configuration of the

boards allows the nails to be concealed, a technique known as blind-nailing.

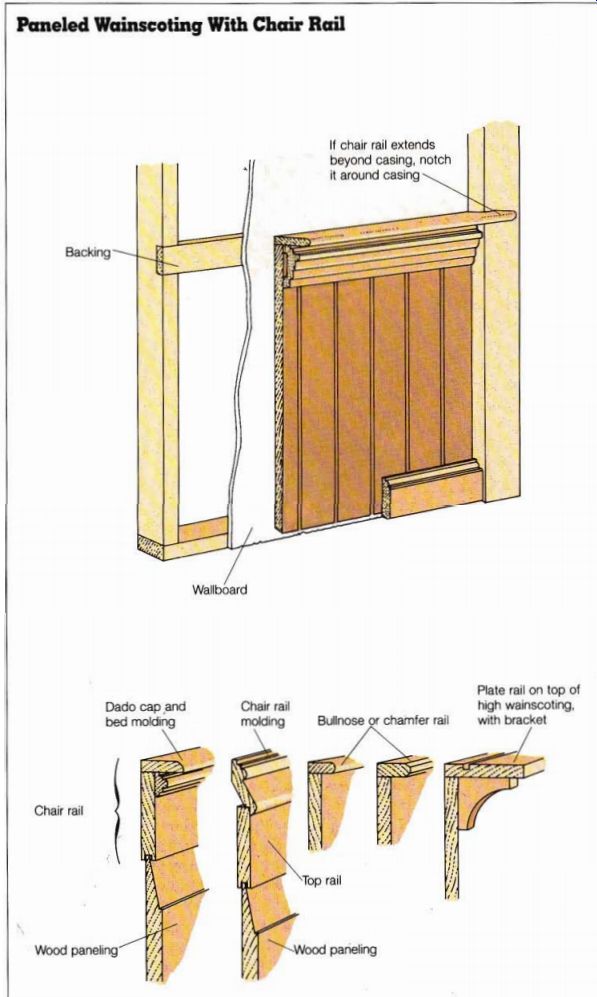

Wainscoting

Wainscoting is decorative wood wallcovering, such as paneling or tongue-and-groove boards,

that is applied to the lower part of a wall. The paneling can be solid wood (square edged or tongue and groove), veneered plywood, or hardboard. The method of installation differs with the type of wainscoting.

Installing Tongue And-Groove Wainscoting

Tongue-and-groove boards are installed perpendicular to the floor. Begin the installation by chalking a horizontal line on the wall to indicate the height of the wainscoting. Measure the pieces so that they will stop just short of the floor and cut them all to length ahead of time. Baseboard will cover the gap at the bottom.

Since each piece must be nailed in at least three places, board wainscoting requires a continuous backing. This is usually provided by letting 1 by 4s into the studs horizon tally before the wallboard is installed. For remodel jobs where there is no access behind the wallcovering, 1/2-inch ply wood can be installed on the surface of the wall to provide backing for the wainscoting.

If there are outside corners, it's better to start with them, since they are especially prominent and visible. You can miter the mating pieces or square-cut them. In either case, glue these pieces together at the corner and nail them 8 inches on center (nail in both directions for a miter). Hold the corner very firmly so that the pieces do not move away from the wall.

Then work your way toward inside corners and window and door casings, nailing each piece at an angle through the tongue into the backing at about 12 inches on center. (Other than the mitered or square-cut out side corner described above, tongue-and-groove joints should not be glued.) At inside corners allow a small gap between the piece and the corner. As you prepare to install the mating piece, consider ripping it to a width that will match the reveal on the piece previously installed. This is a refinement that indicates a more thoughtful approach to the job.

--------

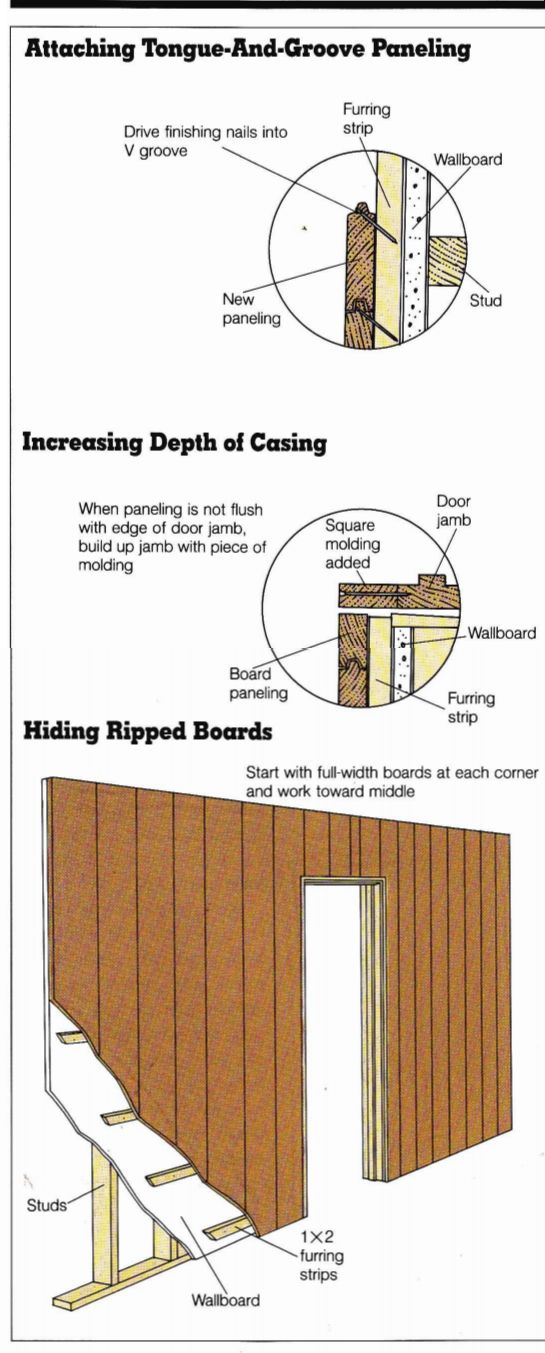

Attaching Tongue-And-Groove Paneling Increasing Depth of Casing Drive finishing nails into V groove Furring strip Wallboard paneling Wallboard When paneling is not flush with edge of door jamb, build up jamb with piece of molding Start with full-width boards at each corner and work toward middle paneling Hiding Ripped Boards Furring strip

--------------- At doors and windows take very careful measurements from the top, middle, and bottom of each casing to the piece of wainscoting previously in stalled. If the measurements are all the same and are less than the width of a full piece, draw a vertical line between the bottom and top marks, allowing a little extra width for adjustment. Cut or plane the piece as necessary to achieve a good it.

If the measurements are different, a line drawn between the top and bottom marks will not align with the middle mark, so draw a vertical line between the top and middle marks, and another between the bottom and middle marks. Cut along these lines to more closely match the contour of the mating piece. Adjust the piece to fit; then facenail it to the backing close to the casing. Set all exposed nail heads. See illustration on page 78.

In very humid climates leave a thin gap beside each piece to allow for expansion and contraction. Use shim material about 0.5 inch thick.

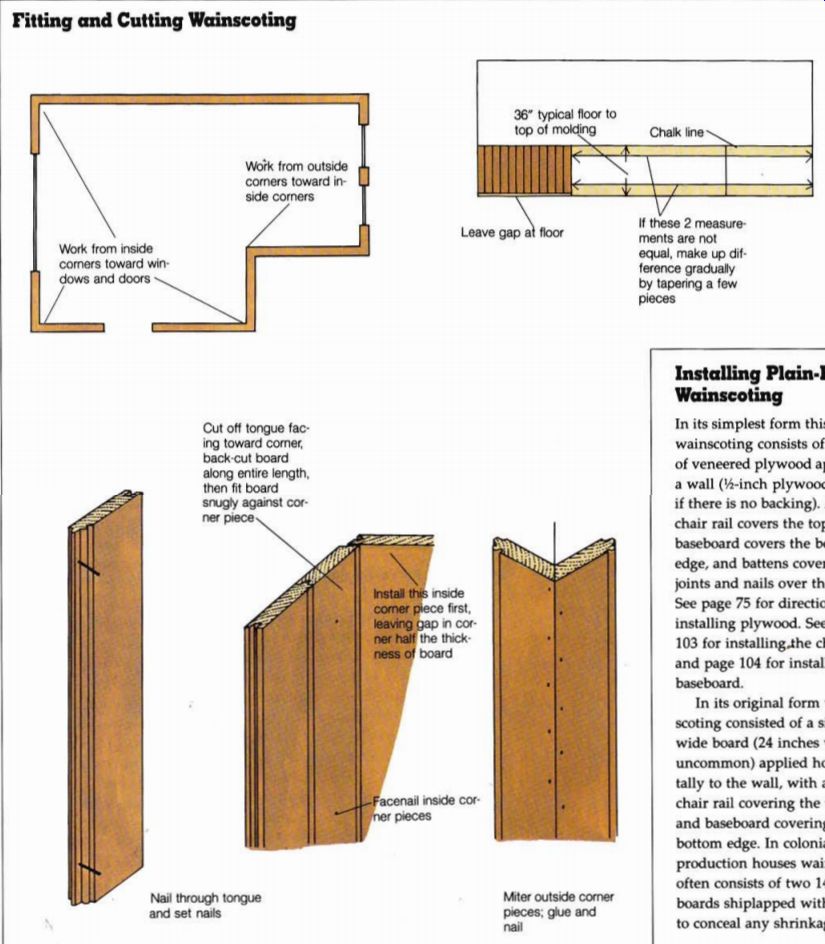

Installing Plain-Panel Wainscoting

In its simplest form this style of wainscoting consists of a sheet of veneered plywood applied to a wall 1/4-inch plywood is best if there is no backing). A cap or chair rail covers the top edge, baseboard covers the bottom edge, and battens cover the joints and nails over the studs.

See page 75 for directions on installing plywood. See page 103 for installing the chair rail and page 104 for installing baseboard.

--------- Titling and Cutting Wainscoting---Work from outside comers

toward in side corners. Work from inside comers toward windows and doors.

Leave gap at floor If these 2 measurements are not equal, make up difference

gradually by tapering a few pieces.

Cut off tongue facing toward corner, back-cut board along entire length, then fit board snugly against corner piece. Install this inside corner piece first, leaving gap in corner half the thickness 6f board facenail inside cornier pieces Nail through tongue and set nails Miter outside corner pieces; glue and nail.

-------------- In its original form wainscoting consisted of a single wide board (24 inches was not uncommon) applied horizon tally to the wall, with a cap or chair rail covering the top edge and baseboard covering the bottom edge. In colonial reproduction houses wainscoting often consists of two 14-inch boards ship-lapped with a bead to conceal any shrinkage.

+++++++++++++++++

CLOSETS

The popular prefabricated modular closet units are designed for the most efficient use of space and easy access. They are discussed below, along with traditional, contemporary, and multipurpose closets. Choose the size and type of closet that will provide you with the storage space you need.

Planning Ahead

Adding a closet requires the same rough framing as installing a non-load-bearing wall.

The framework must be tied into existing studs and joists, so install closets before applying the finish wall, floor, and ceiling surfaces. If this is not feasible, locate studs and joists by referring to the blueprints of the building, by removing some of the finish material, or by using a stud finder.

Check with the local building department to determine whether you will need a building permit (any new electrical wiring will require one). Then draw detailed plans. Bear in mind that you should allow 12 inches behind and at least 12 inches in front of a closet pole. (Remember to allow for finish wall surfaces.) Position the closet wall at a stud location. If necessary, adjust the size of the closet or toenail an additional stud into the existing wall. Frame the opening to fit the closet doors of your choice.

Finally, install the wallcovering and add the shelves, drawers, and poles.

Traditional Closets

A clothes closet needs at least one shelf and a pole. These are usually supported by 1 by 4 cleats fastened to the studs on the side walls and across the back. Allow at least 12 inches behind and in front of the pole.

Its top should be 63.75 inches from the floor. Wood poles that span more than 48 inches will need center support. Wood dowel 1 1/4 inches or 1 3/8 inches in diameter is generally used for closet poles, but W-inch steel pipe works well and is more rigid.

Measuring for Closet Shelves

See page 91 for detailed in formation on measuring for closet shelves.

Installing the Pats

First, attach a cleat to the rear wall of the closet, positioning the top edge 2 3/8 inches above the pole and 66 inches from the floor. Check with a spirit level before nailing or screwing the cleat into the studs (use two nails at each stud). Attach matching side cleats between the rear and front walls. Screw wood or plastic closet pole hangers to the side cleats. Cut the dowel or pipe to length and drop it into the hangers. To prevent the pole from sagging, purchase any of the many metal supports available and attach it to either the wall or the shelf. See illustration. Set all nail heads.

For the shelf cut a 1-by board to length. ( See page 91 for installation procedures.) Finish the front edge with a shaper or a router, or attach a piece of molding with glue and finishing nails.

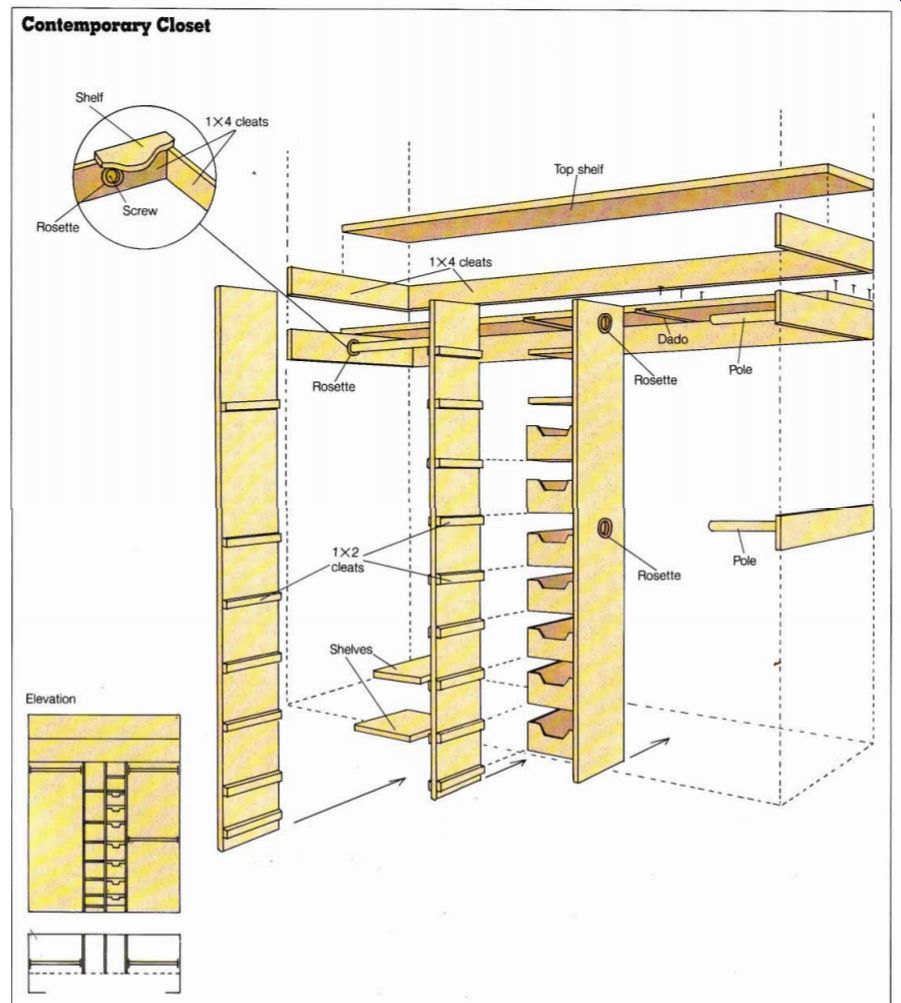

Contemporary Closets

Efficiency has dictated the design of the contemporary closet. Shelves, drawers, and poles are organized to make the best use of space and to provide easy access. This can be achieved in several ways: by using traditional methods of construction but installing the parts in a contemporary configuration; by purchasing prefabricated modular units that it into the available space; or by using a combination of both techniques.

With the traditional method of construction, you begin by creating your own design. Decide how many shelves and dividers you want and the horizontal and vertical dimensions of each. Decide where drawers are to be located and where and how high you want the poles to be.

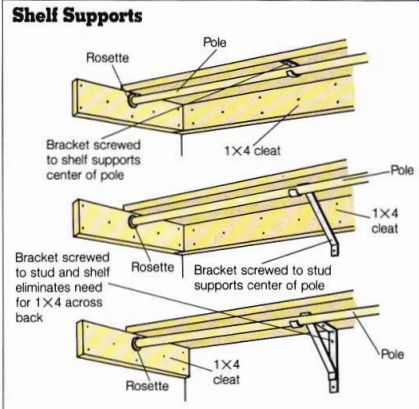

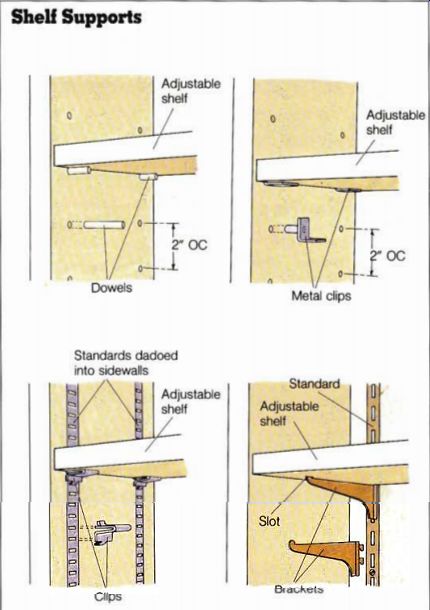

------ Shelf Supports Rosette Pole Bracket screwed to shelf supports

center of pole 1X4 cleat Bracket screwed to stud and shelf eliminates need

for 1X4 across back Pole Rosette Bracket screwed to stud supports center

of pole; Pole

-------------

Start with the side cleats; fasten them to each wall at standard height. Cut and install the shelf (see illustrations on pages 81 and 91). Mark it for vertical dividers. Measure and cut the dividers and install them in their respective positions. Nail through the shelf down into the top end of each divider, using three 6d finishing nails (glue the joint first), and toenail the bottom of each divider to the floor, using three 6d finishing nails on each side.

Cut and install shelves between the dividers. Construct and in stall drawers. ( See page 86 for complete directions.) If the dividers are to contain shelves that will rest on cleats, fasten the cleats to the dividers before you install them. If you’re using shelf clips that will it into predrilled holes, drill the holes before you in stall the dividers. If the dividers will contain drawers, attach the drawer supports at this point.

Mark locations for closet pole hangers and install them.

(If you want several poles, you will need additional side cleats to hold the extra hangers.) Measure and cut the poles and drop them into place.

A second shelf 12 inches above the first shelf provides storage space for little-used items. If you want a second shelf, install it last.

Prefabricated modular units are usually assembled on-site.

They may require no fasteners other than those supplied with the unit. Install these units according to the instructions included in the package.

A combination installation procedure may be desirable with non-wood closet units. For example, plastic-covered metal standards, shelves, and baskets have found widespread use in residential construction and are reasonably economical. When using these install the main shelf first. Next, install the up per storage shelf. Then purchase the unit of your choice to ill the space below the main shelf most efficiently. Modular units come in a wide variety of sizes and shapes; choose the ones that best it your needs.

Multipurpose and Specific-Use Closets

Closets in family or activity rooms usually require more shelving than clothes closets and seldom have poles. Linen closets ordinarily contain a series of shelves, located at heights convenient to the user.

Guest rooms usually have small traditional closets.

Closet Doors

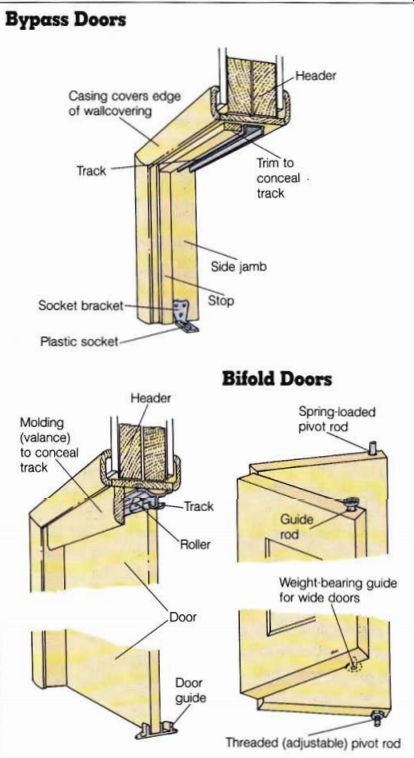

Choose a conventional swinging door ( see page 99 for how to trim) or a sliding (bypass) door or an accordion (bifold) door (see illustration).

Bypass doors come either 0.75 inch or 1 3/8 inches thick. They are mounted on an exposed upper track or on a track built into the head jamb.

For a built-in track, the doors and the frame are ordered as a unit. Cover the gap between the frame and the finished wall surface with casing.

A less expensive method is to frame the rough opening (either top and sides or across the top only) with 1-by jamb stock cut as wide as the wall is thick (including wallboard on both sides). Nail this frame to the header and the trimmers.

Measure and cut a length of sliding-door track and screw it to the head jamb. Position the track to allow for the thickness of the doors (and a trim valance, if one is needed).

Trim the door panels to size, if necessary, and attach roller hardware to the top corners on the back of each door. Lift the doors onto the track (tilt them in order to do so), and check for it and smooth operation. To make adjustments loosen the screws in the roller hardware and lower or raise the door as necessary. Tighten the screws before removing the doors in order to mount the valance.

Attach the valance either by screwing it directly to the finish wall or by hanging it from corner angles mounted to the head jamb. (Make sure that the doors will clear the valance.) Apply casing around the opening. Re-hang the doors and screw or nail stops and guides into the finish floor.

Installation of bifold doors is the same as that for bypass doors; only the hardware differs. If the door has two panels and is more than 3 feet wide, support the sliding end with a special weight-bearing slider.

On narrower doors a simple locating pin is sufficient.

----- Header Casing covers edge of wallcovering / trim to conceal track

Socket bracket Plastic socket Bifold Doors Header Spring-loaded pivot rod

Molding (valance) to conceal track \ .

Guide rod Weight-bearing guide for wide doors Threaded (adjustable) pivot rod Bypass Doors

----------------

--------- Contemporary Closet

+++++++++++

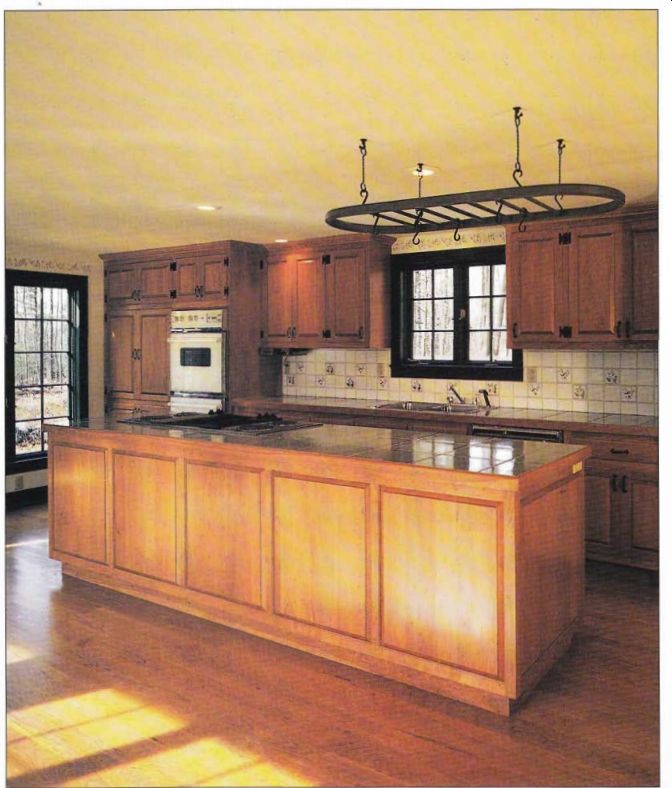

CABINETS

Cabinets are the showpiece of most kitchens.

They represent a large share of the cost of renovation as well. If you would like to extend your finish carpentry skills and make your own cabinets, the following explanations will guide you through the process.

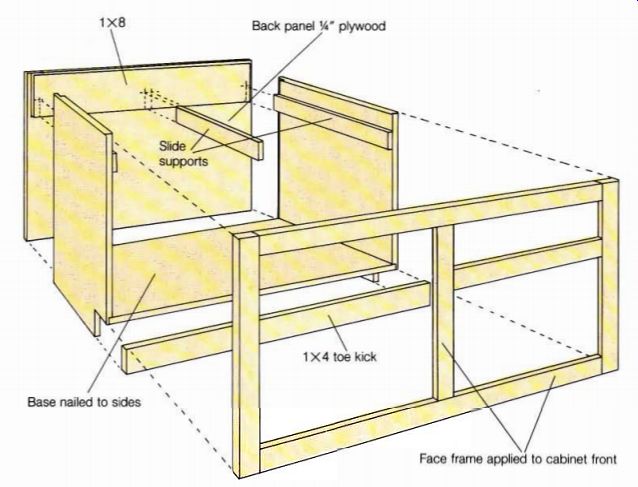

Organize the Sequence of Construction

Begin by grouping the construction into phases. The first phase is cutting and assembling the basic case: ends, partitions, fixed shelves, bottom, and back. The second phase is attaching the face frame. It can be completely assembled first and then attached to the base as a unit, or it can be glued and nailed to the base in separate pieces. The third phase is building the doors and drawers, and the fourth phase is making toe kicks and underlayments for the lower units.

To begin each phase, pre pare a detailed cut list of all the pieces that you will need. A cut list is simply a list of cabinet parts in the final cut size. It is important to make a complete list for each phase in order not to waste stock. For instance, if you know ahead of time that you will need three 36-inch pieces of 1 by 2, you can use a 10-foot length instead of three 4-foot lengths.

Wall Cabinets Until recently the traditional method of installing wall and base cabinets was to build and fasten them to the wall piece by piece.

------ Noticing some of the details in these solid cherry cabinets

crafted by a fine cabinetmaker will help when planning your own kitchen. The

colonial style of the room is enhanced by paneled lipped doors ( see page

85) and exposed offset H-hinges painted flat black.

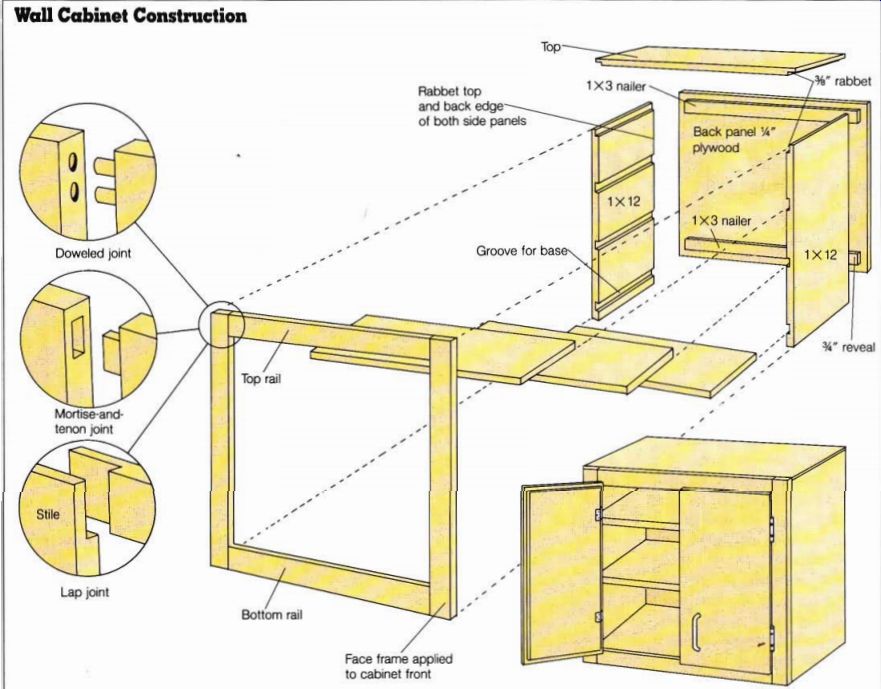

--------- Wall Cabinet Construction

Nowadays, however, it is standard practice to construct the units completely before in stalling them. This approach is quicker, easier, and much less awkward.

Since it is usually simpler to attach the wall cabinets before the base units are in place, make the former first. Remember that full cabinets are very heavy. Always use strong joints and always fasten each unit to the studs.

Standard manufactured wall cabinets are usually 12 inches deep and are generally fastened to the wall 18 inches above the countertop. You can use any dimensions you like, but the standard dimensions provide the most efficient clearance.

Constructing Wall Cabinets 1.

Using 1 by 12 appearance grade stock, cut the side, top, and bottom pieces of the cabinet to length. If you prefer, cut these pieces out of plywood that is finished on both sides.

Cut rabbets in the side pieces to accept the top of the cabinet and the plywood back, and dadoes to accept the bottom of the cabinet and the shelves. (The depth of the dado cuts should be 3/8 inch.) If you prefer adjust able shelves, see page 92. The dado for the bottom of the cabinet should be positioned to al low the face frame to cover the edge (see illustration). Apply glue to the ends of the bottom of the cabinet, it the bottom into the dadoes of each side piece, and nail the bottom in place with 4d finishing nails.

Fit the top of the cabinet into the rabbets on each side piece (after applying glue to the edges) and nail in place.

2. Set the cabinet on its face in order to install the back 1 by 3 nailing cleats. Square up the cabinet. Glue and fasten the 1/3 inch plywood back in place, preferably with staples or cement-coated nails.

3. Set the cabinet on its back. Cut the shelves to length (remember to allow for the depth of the dadoes). Apply glue to the edge of the shelves at each end, slide the shelves into the cabinet, and nail them in place.

4. Cut 1 by 2 strips for the face frame and assemble it, using either doweled, mortise and tenon, or lap joints. (Correct measurements are essential, since the frame determines the dimensions of the door opening.) Glue and clamp the joints. Wipe off excess glue with a damp cloth before it sets. When it is dry nail the face frame to the front edges of the cabinet. Set all nails and fill the holes.

Base Cabinets

When you make your own cabinets, you can design them to suit yourself. However, re member that appliances such as dishwashers, stoves, ovens, and refrigerators are made to fit standard-sized cabinets. For kitchen base cabinets the standard dimensions are 35 1/4 inches high (not including the countertop) and 24 inches deep. Bathroom vanity cabinets are generally 30 inches high, although 36-inch cabinets are becoming more popular. The width of the vanity is determined by the size and shape of the washbasin.

If you have a long line of base cabinets, such as a kitchen peninsula or wall unit, you can either build it as a single assembly or build several smaller units and attach them together, as described for wall cabinets on page 87.

Constructing Base Cabinets 1.

From 3/8-inch stock cut two side panels 23.25 inches by 35.25 inches. Cut a 3.5-inch-square notch at the lower front corner of each panel. See illustration.

2. On the inner side of each panel, dado a -3/8-inch-wide by 3/8-inch-deep groove from front to back. The bottom edge of the groove should be even with the top of the 3.5-inch notch. These grooves will support the bottom panel. Cut a 3/8-inch-wide by 1/4-inch-deep rabbet on the inside back edge of each side piece. These rabbets will accept the back panel, which will be cut out of 1/4-inch plywood.

Dado additional grooves if you plan to install any fixed shelves or adjustable shelf standards ( see page 92); or drill holes for adjustable shelf supports.

3. From 3/8-inch sheet material cut a base panel 23 inches wide by the length of the cabinet less 3/8 inch. From 1 by 8 stock cut a nailer the length of the cabinet less 0.5 inch.

4. Following the sequence described for the wall cabinets, assemble the pieces, using glue and nails. Check for square.

Then hold in position while you nail the plywood back.

5. Make a face frame out of 1 by 2 clear stock. Cut two stiles (vertical pieces) to the full face length of the sides. Cut the rails (horizontal pieces) to fit be tween them. Cut stiles for the vertical dividers (mullions) and rails for the drawer divisions.

Glue, clamp, and assemble the frame before attaching it to the cabinet; wipe all excess glue from joints before glue dries.

Mount the frame in place with finishing nails. Set all nails and fill the holes.

--------- Base Cabinet Construction

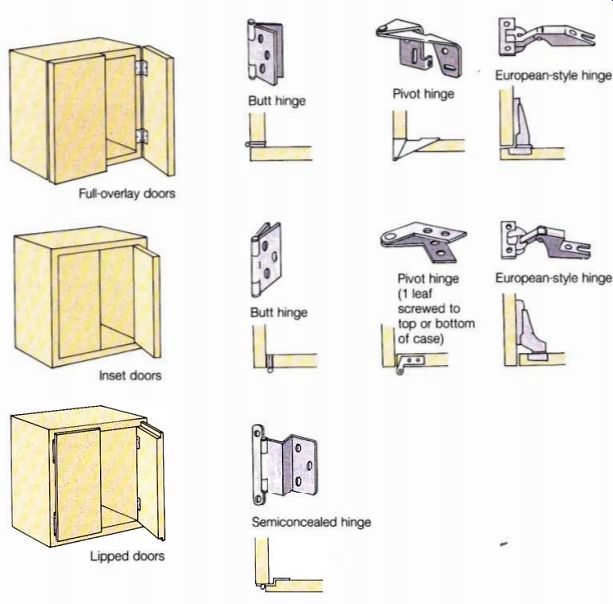

Cabinet Doors

Hinged doors can be lush mounted, full-overlay, or lipped. See illustration to com pare the styles and the hard ware required for each.

Flush Doors

Cut doors to match the size of the opening; they will lie lush with the outside face of the frame. An inset European-style hinge is the most popular type.

With this type of hinge, holes are bored on the inside of the door to accommodate the wafer section of the hinge so that it will fit snug and lush. The other section of the hinge mounts on the inside of the cabinet. Although it costs a good deal, this type of hinge is popular because you can make wide adjustments to align the doors. Butt or pivot hinges are a less expensive option.

Full-Overlay Doors

Cut the doors to match the outside dimensions of the face frame. The full-overlay European-style hinge is the most popular choice for this type of cabinet door. You can also use butt hinges screwed to the front face of the frame and the inside face of the door, or angled or lat pivot hinges screwed to the top and under side of the cabinet and the inside face of the door.

Lipped Doors

These are a combination of full overlay and lush doors. The inside face fits inside the opening, and the outside face over laps the frame. Cut the doors to a size that gives the desired amount of overlap; then cut rabbets around the edges. If there is a divider in the cabinet, or if the cabinet has only one door, rabbet all four edges. If there are double doors but no divider, do not rabbet the edge that butts against the other door. Use semi-concealed 3/8 inch inset self-closing hinges for mounting the doors. (The narrow leaf will be exposed on the face frame.)

Door Hardware

Most hinges nowadays are spring loaded and do not re quire any special type of catch.

However, in cases where special catches are needed, there are many types to choose from.

Mount each catch beneath one of the shelves or on a mullion or stile, so that it will be out of the way. The choice of knobs, pulls, and handles is also a matter of personal preference. To mount, carefully mark all doors so that the knobs align horizontally and, if possible, vertically as well.

--------- Cabinet Doors and Hinges Full-overlay doors; Inset doors

Lipped doors Butt hinge Butt hinge Pivot hinge (1 leaf screwed to top or bottom

of case)

Semi-concealed hinge European-style hinge European-style hinge

--------------

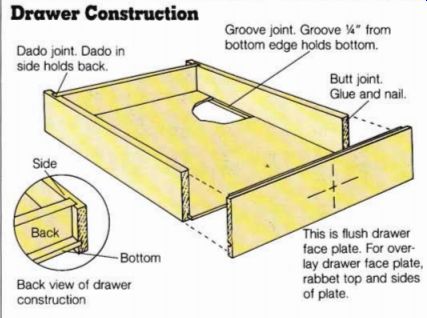

----------- Drawer Construction Dado joint. Dado in side holds back.

Groove joint. Groove 1/4" from bottom edge holds bottom.

Butt joint.

Glue and nail.

Back view of drawer construction This is flush drawer face plate, For over lay drawer face plate, rabbet top and sides of plate

---------------

Drawers

A drawer is simply an open faced box. It can be made out of 0.5-inch or 3/8-inch board stock, plywood, or special high-pressure particleboard. The latter material, which is coated with a tough, scratch-resistant laminate, is becoming very popular.

Traditionally the sides of drawers were dovetailed into the front and back piece to make solid joints. If you don’t own a dovetail jig for your router, use dadoes and grooves to make a strong drawer. See illustration.

1. Cut the side and front pieces to length and cut dado grooves in them to receive the base of the drawer. These grooves should be !4 inch from the bottom of each piece. Cut the back piece to length and dado the side pieces to accept the back. Assemble the pieces;

if they fit, glue and nail the sides together. Apply glue to the edges of the base, slide it into the grooves on the side pieces, and clamp until dry.

2. For a full overlay drawer, the face plate should overlap the drawer opening by about Vi inch on all four sides. Cut the face plate to length out of 0.5 inch or 3/8-inch appearance grade stock. If you wish you can carve a design on the front or chamfer the edges with a router. Attach the face plate to the drawer with two screws.

Use screws long enough to grip, but not to penetrate, the plate. Make sure that the face plate is centered on the opening rather than on the drawer.

(The slides may make the drawer sit slightly off center.)

3. Drawers can be supported by slides mounted on each side of the drawer cavity. For side supports to hold the slides, nail 1 by 2 rails to the outer walls of the cabinet and 2 by 2 rails to the vertical center partition and to an additional vertical sup port placed between the cabinet floor and the rear wall support.

4. It is easier to install the sliding hardware before the countertop is in place, so do this next. The local building supply outlet should have a variety of mechanisms from which to choose. It is also easier to install the counter supports now. Nail them between the rear wall support and the face frame every 2 feet, except where you need a larger opening for the sink.

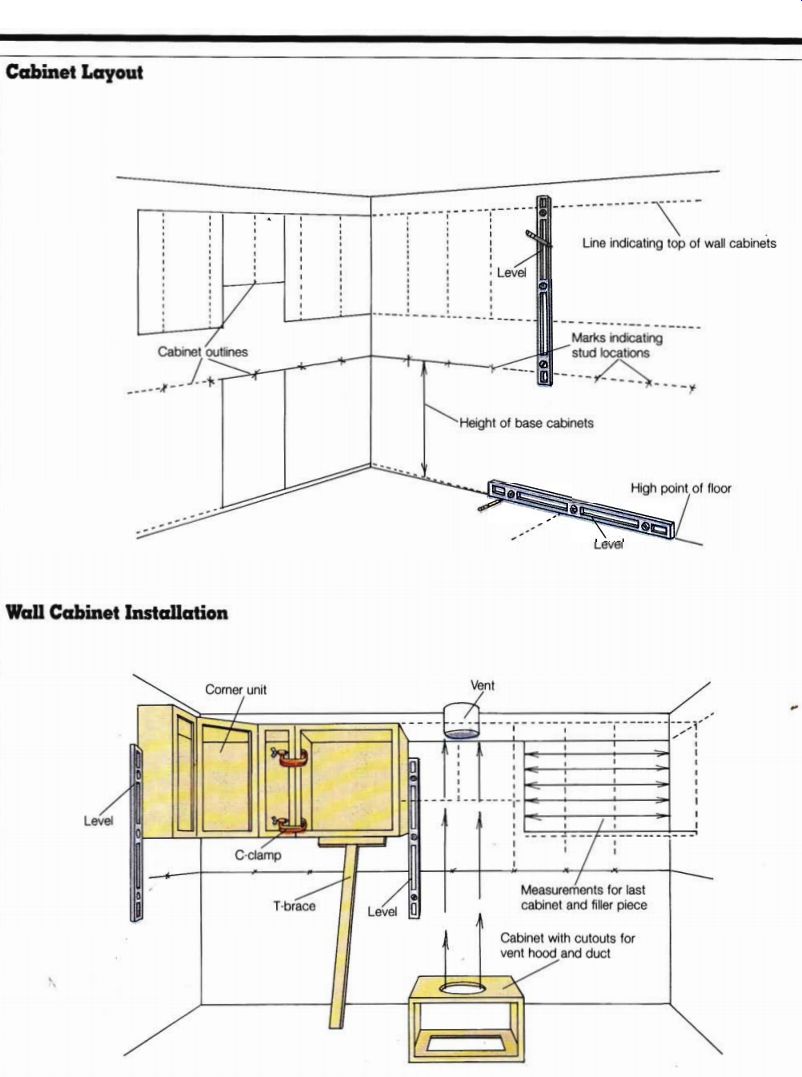

Installing Cabinets

Whether you have constructed your own kitchen cabinets or purchased ready-made units, installing them is a meticulous and demanding task. It’s easy to underestimate the time required to do it right. For a kitchen of average size, figure on putting in about a week of work.

In a successful cabinet installation, the units are level, plumb, and square; all joints are tight and flush; and the doors and drawers are aligned.

Carefully study the following techniques, and the manufacturer’s instructions if you’re in stalling purchased units, before you start to work. The following description applies to purchased units, but it can also be used for units that you‘ve constructed yourself. Note especially the differences between frame and frameless cabinet installations. There is no margin for error with frameless cabinets; if they are not perfectly square and straight, then the doors and drawers will not it properly.

Preparation

Cabinets are installed relatively late in the construction sequence. All the walls and ceilings should be smooth, and the soffits, if any, should be finished, unless you are adding them later. Painting should be completed, wallcoverings may be up, and wiring for under counter lighting should be in stalled. If the finish floor is down, protect it with plywood or cardboard while the cabinets are being installed. Remove paintings and other valuable objects from the walls.

The tools you will need are a 3/8-inch or 0.25-inch electric drill, preferably variable-speed; a countersink bit; an assortment of screwdrivers; a tape mea sure; a hammer; 2-foot and 4 foot levels; a 6-foot straightedge or a long level; adjustable clamps or C-clamps; a stepladder; shims; a flat prybar; masking tape; and a bar of soap.

An extra electric drill with a Phillips-screwdriver bit is handy to have. You will also need a supply of 1/4-inch, 2 1/2 inch, and 3-inch quick-drive wood screws; 3d, 4d, and 6d finishing nails; 1-inch brads; and whatever special connecting screws are provided with frameless cabinets.

Inspect all the cabinets for defects and verify the sizes.

Make sure that the doors it, that none of the boxes is warped, and that all the drawers slide perfectly. Remove all the doors; mark on each door which cabinet it belongs with; and put the cabinets back into the cartons. Store them until you need them.

Start the layout for the cabinets by locating the highest point of the floor in the area where the base units will be installed. See illustration on page 88. Use a long level or a straightedge with a level on it.

If the highest point is not against the wall, use a level and a pencil to transfer the height of that point to the wall. Having marked the wall at the appropriate height, measure up from the mark and make a second mark at the height of the base cabinets (usually 34 1/2 inches). Add an allowance for the thickness of the finish floor if it is not yet down and make a third mark. Using the straight edge and a level, draw a line on the wall at this third mark. This line represents the tops of all the base cabinets. (The line will be covered by the counter or the backsplash. Make heavy marks on the wall only where they will be covered; elsewhere use a faint pencil line.) Now draw another level line for the tops of the wall cabinets. Most wall cabinets are 30 inches tall and are positioned 18 inches above the countertop. For most installations, then, this line will be exactly 84 inches (36 + 18 + 30) above the highest point of the floor.

If the wall cabinets extend up to a soffit or up to the ceiling, check them for level.

Find the lowest point of the ceiling or soffit in the area over the cabinets and draw a level line on the wall at that height for the cabinet tops. You can now see how much of a gap there will be between the ceiling or soffit and the cabinets.

After the cabinets are installed, cover this gap with a strip of molding.

If the installation includes a full-height cabinet, measure it now to make sure that it will it beneath the ceiling or soffit.

You may have to trim the top or the base, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Using the lines on the wall for horizontal guides and a level for plumb, lay out the cabinet dimensions on the wall.

Make sure that they line up properly with each other and with the various corners, windows, sinks, appliances, and so forth. Make any necessary adjustments.

Next, mark the location of each stud just above the line for the base cabinets, in the area where the upper cabinets will be hung. To find a stud, tap lightly on the wall and listen for a solid sound. Probe the area with a hammer and nail until you locate both edges of the stud. Mark the exact center of the stud on the wall. Using a level, draw a vertical line through this mark. Repeat for each stud behind the upper cabinets. If there is blocking between the studs, mark a horizontal line at the center of the blocking where the cabinets will be hung.

It is usually easier to install the wall cabinets before the base cabinets. However, if the back splash will be full-height laminate that extends up to the wall cabinets, the base cabinets and the countertop must be in stalled first. It is also better to install the base cabinets first if there is a full-height cabinet in the middle of a run.

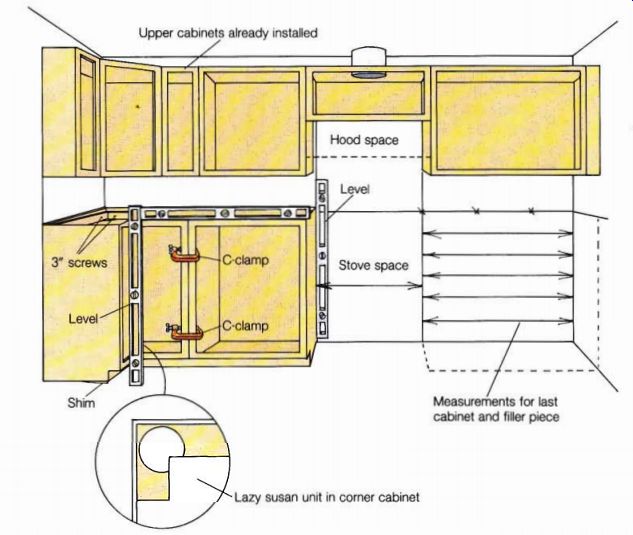

Installing Wall Cabinets

Start a run of wall cabinets with a full-height unit or a corner unit if you have one.

Otherwise start at whichever end will not require a filler piece. The first cabinet is the most critical-it must be perfectly level, plumb, and square, or the entire run will be out of alignment.

Measure where the studs line up behind the first cabinet and transfer these measurements to the inside of the cabinet at the top and bottom hanger rails. See illustration on page 88. Countersink and drill holes through the back of the cabinet at these marks; make the holes just large enough for the 3-inch screws.

If the cabinets are frameless, they may require a metal sup port rail, provided by the manufacturer. Install this rail next.

It must be attached to the wall behind the cabinets, which will be hung from it. Cut the rail to length and screw it securely to each stud at the height recommended by the manufacturer.

There are several methods for holding the cabinets in place while you attach them to the wall. One is to build a T brace slightly longer than the distance between the floor and the bottom of the cabinet. An other method, used when the base cabinets are installed first, is to build a simple rectangular frame out of 2 by 4s; this frame should be just high enough to support the wall cabinets when it sits on a makeshift counter top. A third method can be used if the walls have not yet been finished. Simply screw a 1-by cleat to the wall to support the bottom of the cabinets. A specialty jack is useful here, if you know a professional who might lend you one.

To begin, lift the first cabinet into place and slide the brace up Under it. You will need a helper to stabilize the cabinet while you do this. At tach the cabinet to the studs with 3-inch screws, tightening only one of the top screws and leaving the others slightly loose. Place a shim behind the cabinet, next to a screw, at any point where the wall bows in ward. Use a level to check that the cabinet is plumb and horizontal in all directions.

Now transfer the stud dimensions to the inside of the second cabinet and countersink and drill the screw holes. Drill two more screw holes through the vertical stile on the side that will be attached to the first cabinet. Drill where the hinges will cover up the screw heads.

For frameless cabinets the side holes are already partially drilled, about 3 inches back and 2 to 3 inches up from the bottom or down from the top.

Simply complete the drilling.

Special fasteners go into these holes; they screw into each other, leaving a smooth head on each side that is covered with a plastic cap.

Lift the second cabinet into place and support it, but do not screw it into the back wall.

Instead, clamp the two cabinets together so that the joint be tween them is tight and flush.

Use wood shims to protect the cabinet finish from the clamps.

Choose a drill bit slightly smaller than the shank of a 1 1/2 inch screw and center it in the ...

--------- Cabinet Layout Wall Cabinet Installation

---------

--------- Base Cabinet Installation

---------

... first side hole of the second cabinet. Drill about two thirds of the way into the adjoining stile of the first cabinet.

Do the same for the second side hole. Now lubricate two 1 1/2-inch screws with bar soap and drive them firmly into the holes that you have just drilled.

If the cabinets are tall or if the face frames do not align perfectly, predrill more holes and add more screws. Then attach the cabinet to the back wall, in the same way as you did the first cabinet.

Repeat this process for all the wall cabinets in the same run. If a vent hood will be mounted to a wall cabinet, cut holes in the cabinet for the duct before you install the cabinet.

If the final cabinet will end next to a sidewall, there may be a gap that needs a filler piece.

These come in 3-inch and 6 inch widths and must be cut to it snugly. Before you install that cabinet, attach the filler piece to the stile in the same way as you would attach two cabinets together. Then take a series of measurements be tween the wall and the last cabinet installed. Transfer these measurements to the face of the final cabinet, marking them on the filler piece. Now connect the marks with a line. Cut along the line with a fine toothed keyhole saw, angling the back of the cut toward the cabinet. The cut will follow any deviations in the wall so that the filler piece will it perfectly.

Filler pieces for corners are in stalled in the same way, but they need not be scribed and cut. Some manufacturers pro vide cabinets with wide stiles, called ears, already attached.

These ears function as filler pieces and are trimmed in the same way.

When the full run of wall cabinets is in place, check for level, plumb, and square (mea sure diagonals). Use shims to make any necessary adjustments, loosening the back screws to slip the shims into place. After all the screws are tightened, make a final check.

Be especially careful with frameless cabinets. The slightest warp will make the doors hang crooked.

Installing Base Cabinets

Frame and frameless base units are installed in the same way as wall cabinets, except that with the frameless style there is no margin for error. Start with a corner unit, unless a cabinet in the middle of a run must be perfectly aligned with some other feature, such as a window or the sink plumbing. Set the cabinet in place and shim un der the base until the top is even with the layout line.

Countersink and drill through the top rail at each stud and attach the rail to the stud with 3-inch screws.

If the wall is not straight, place shims behind the cabinet, using a level to check the top, sides, and front.

Hold the level against the frame and not against a door or drawer.

Set the second unit in place and attach it to the first unit, using the method described on page 87 for wall cabinets.

Screw it to the back wall. See illustration on page 89.

Complete the run of base cabinets. Some of them, such as lazy susan corner units and sink fronts, have no box to attach to the wall. They are held in place only at the face frames. (With frameless styles the sink fronts have sides that extend back just far enough to attach them to the adjacent cabinets.) Because these units have no backs, you will have to provide support for the countertop along the backside. Screw cleats of 1-by lumber to the wall just below the layout line.

You will also need to fabricate a floor for some sink fronts. Cut it out of a piece of 0.5-inch to 3/8-inch plywood and support it on cleats screwed to the wall and to the adjacent cabinets. Seal it or paint it be fore you install it.

If there will be an appliance in the middle of a run--a dish washer, trash compactor, or slide-in range-you must allow for it when you install the base cabinets. Check the appliance specifications to determine the exact width of the space. To keep the cabinets on both sides aligned, bridge the gap with a long straightedge at the front and back. Install filler pieces at the end of the run and at the corners, just as you did for the wall cabinets.

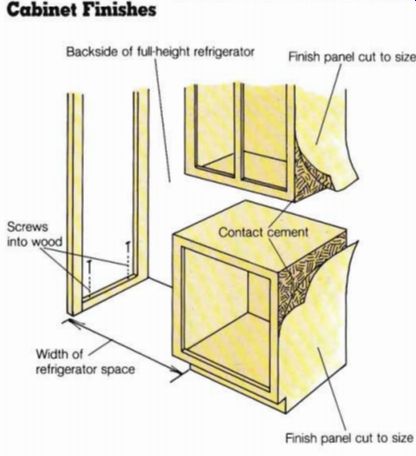

Finishing Touches

Finish panels, doors, trim, and handles are the most noticeable features of a cabinet installation. Take care to attach them correctly. Try to set aside one day just to do this part of the job; don’t try to do it at the end of a long day‘s work.

In some lines of manufactured cabinets, finish panels must be installed on all the exposed faces of every unit.

These panels come either pre-cut or as a full sheet of ply wood paneling from which you cut out each piece to it. If the panels have grain patterns, match each one carefully with the patterns on the adjacent cabinets.

Measure and cut each panel to size. Spread contact cement on the back of each panel and on the side of the cabinet where the panel will be positioned. Let it set for the amount of time given in the instructions. Press the panel in place, clamp it, and leave it overnight to dry. See illustration. If necessary, use 3d nails to help hold it in place. The nail heads can be countersunk and the holes filled with putty after the cement dries.

-----

When you put the doors back on the cabinets, some of them may not line up perfectly.

Most hinges have a mechanism for making slight adjustments to correct this problem.

Before you install trim pieces, be sure that the cabinets are aligned and securely fastened. Cut the trim to length with a miter box, and stain or paint the trim, including the cut ends, before you attach it.

Predrill the trim and fasten it with 3d, 4d, or 6d finishing nails. Sink the heads with a nail set and fill the holes.

For frameless units attach the trim pieces from inside the cabinet, using screws. Predrill holes through the cabinet large enough to take the screws; use a smaller bit to drill pilot holes in the trim itself. Most manufacturers provide plastic caps to cover the screw heads.

To finish the toe kick, cut baseboard or similar molding to length and paint or stain it a dark color. Attach it to the cabinet kicks with finishing nails.

+++++++++++++++++

SHELVES

You can use shelves in almost every room of the house: for cookware in the kitchen, for towels in the bathroom, for books in the den, for china in the dining room. Shelves are also necessary in kitchen and bathroom cabinets and in linen and miscellaneous storage closets.

Types of Shelves

There are two distinct types of shelves. One is custom-fitted between two sidewalls and a rear wall in a closet. The other is square cut and positioned between two finished side pieces in a cabinet or bookcase.

The first is permanently fastened in place; the second can be either permanently fastened or adjustable.

Fitted Shelves

Custom-fitted shelves are used in closets and freestanding bookcases.

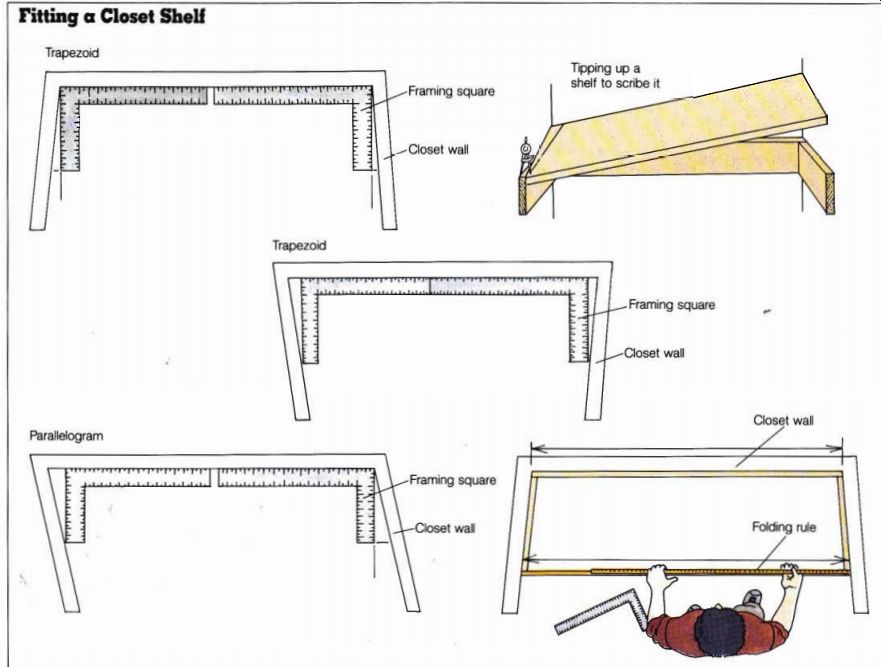

------ Fitting a Closet Shelf--- Trapezoid Tipping up a shelf to scribe it; Trapezoid; Framing square

In Closets

To make custom-fitted shelves for a closet, start by measuring between the sidewalls at the height for each shelf. For closets with several shelves, start at the bottom and work your way up. (The cleats should be in place.) Take measurements between the side walls at the front and the back of the closet; they will probably not be parallel to each other or square with the rear wall. Walls are seldom exactly true.

Now check the corners with a framing square. Position the long leg of the square against the rear wall and move it to ward a corner. If the corner of the framing square touches the sidewall before the short leg touches it, note the gap be tween the wall and the short leg of the square. Repeat this procedure at the opposite side wall. If there is a gap on both sides, the shelf board will be trapezoidal when it is cut to fit.