Implementing a Balanced Scorecard

Drs. Robert Kaplan and David Norton developed another approach to help select and man age projects that align with business strategy. A balanced scorecard is a methodology that converts an organization's value drivers, such as customer service, innovation, operational efficiency, and financial performance, to a series of defined metrics. Organizations record and analyze these metrics to determine how well projects help them achieve strategic goals. Using a balanced scorecard involves several detailed steps. You can learn more about how it works from the Balanced Scorecard Institute (www.balancedscorecard.org)or other sources. Although this concept can work within an IT department, it is best to implement a balanced scorecard throughout an organization because it helps foster alignment between business and IT.

========

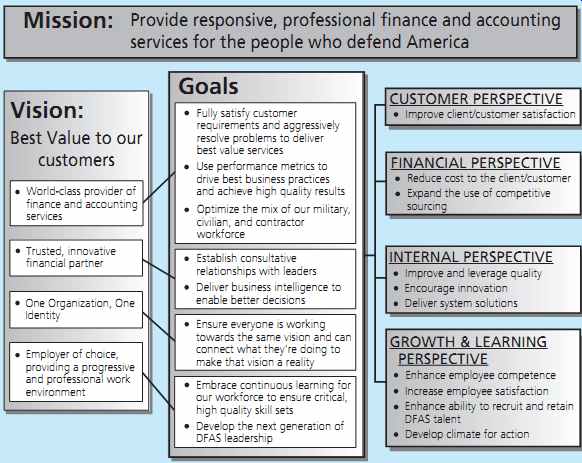

FIG. 8 Balanced scorecard example

Provide responsive, professional finance and accounting services for the people who defend America Best Value to our customers

Improve client/customer satisfaction

CUSTOMER PERSPECTIVE FINANCIAL PERSPECTIVE

Reduce cost to the client/customer

Expand the use of competitive sourcing

INTERNAL PERSPECTIVE GROWTH & LEARNING PERSPECTIVE

Improve and leverage quality Encourage innovation Deliver system solutions Enhance employee competence Increase employee satisfaction Enhance ability to recruit and retain DFAS talent World-class provider of finance and accounting services Trusted, innovative financial partner One Organization, One Identity Employer of choice, providing a progressive and professional work environment Embrace continuous learning for our workforce to ensure critical, high quality skill sets Develop the next generation of Ensure everyone is working towards the same vision and can connect what they're doing to make that vision a reality Establish consultative relationships with leaders Deliver business intelligence to enable better decisions Fully satisfy customer requirements and aggressively resolve problems to deliver best value services Use performance metrics to drive best business practices and achieve high quality results Optimize the mix of our military, civilian, and contractor workforce

=========

The Balanced Scorecard Institute's Web site includes several examples of how organizations use this methodology. For example, the U.S. Defense Finance and Accounting Services (DFAS) uses a balanced scorecard to measure performance and track progress in achieving its strategic goals. Its strategy focuses on four perspectives: customer, financial, internal, and growth and learning. FIG. 8 shows how the balanced scorecard approach ties together the organization's mission, vision, and goals based on these four perspectives. The DFAS continuously monitors this corporate score card and revises it based on identified priorities.

As you can see, organizations can use many approaches to select projects. Many project managers have some say in which projects their organizations select for implementation. Even if they do not, they need to understand the motives and overall business strategies for the projects they are managing. Project managers and team members are often called upon to explain the importance of their projects, and understanding project selection methods can help them represent the project effectively.

Developing a Project Charter

After top management decides which projects to pursue, it is important to let the rest of the organization know about these projects. Management needs to create and distribute documentation to authorize project initiation. This documentation can take many different forms, but one common form is a project charter. A project charter is a document that formally recognizes the existence of a project and provides direction on the project's objectives and management. It authorizes the project manager to use organizational resources to complete the project. Ideally, the project manager provides a major role in developing the project charter. Instead of project charters, some organizations initiate projects using a simple letter of agreement, while others use much longer documents or formal contracts. Key project stakeholders should sign a project charter to acknowledge agreement on the need for and intent of the project. A project charter is a key output of the initiation process, as described in Section 3.

The PMBOK® Guide, Fifth Edition lists inputs, tools, techniques, and outputs of the six project integration management processes. For example, the following inputs are helpful in developing a project charter:

• A project statement of work: A statement of work is a document that describes the products or services to be created by the project team. It usually includes a description of the business need for the project, a summary of the requirements and characteristics of the products or services, and organizational information, such as appropriate parts of the strategic plan, showing the alignment of the project with strategic goals.

• A business case: As explained in Section 3, many projects require a business case to justify their investment. Information in the business case, such as the project objective, high-level requirements, and time and cost goals, is included in the project charter.

• Agreements: If you are working on a project under contract for an external customer, the contract or agreement should include much of the information needed for creating a good project charter. Some people might use a contract or agreement in place of a charter; however, many contracts are difficult to read and can often change, so it is still a good idea to create a project charter.

• Enterprise environmental factors: These factors include relevant government or industry standards, the organization's infrastructure, and marketplace conditions. Managers should review these factors when developing a project charter.

• Organizational process assets: Organizational process assets include formal and informal plans, policies, procedures, guidelines, information systems, financial systems, management systems, lessons learned, and historical information that can influence a project's success.

The main tools and techniques for developing a project charter are expert judgment and facilitation techniques, such as brainstorming and meeting management. Experts from inside and outside the organization should be consulted when creating a project charter to make sure it is useful and realistic. Facilitators often make it easier for experts to collaborate and provide useful information.

The only output of the process to develop a project charter is the charter itself.

Although the format of project charters can vary tremendously, they should include at least the following basic information:

• The project's title and date of authorization

• The project manager's name and contact information

• A summary schedule, including the planned start and finish dates; if a summary milestone schedule is available, it should also be included or referenced

• A summary of the project's budget or reference to budgetary documents

• A brief description of the project objectives, including the business need or other justification for authorizing the project

• Project success criteria, including project approval requirements and who signs off on the project

• A summary of the planned approach for managing the project, which should describe stakeholder needs and expectations, important assumptions, and constraints, and should refer to related documents, such as a communications management plan, as available

• A roles and responsibilities matrix

• A sign-off section for signatures of key project stakeholders

• A comments section in which stakeholders can provide important comments related to the project

Unfortunately, many internal projects, like the one described in the opening case of this section, do not have project charters. They often have a budget and general guide lines, but no formal, signed documentation. If Nick had a project charter to refer to--especially if it included information for managing the project--top management would have received the business information it needed, and managing the project might have been easier. Project charters are usually not difficult to write. The difficult part is getting people with the proper knowledge and authority to write and sign the project charter. Top management should have reviewed the charter with Nick because he was the project manager. In their initial meeting, they should have discussed roles and responsibilities, as well as their expectations of how Nick should work with them. If there is no project charter, the project manager should work with key stakeholders, including top management, to create one. Table 1 shows a possible charter that Nick could have created for completing the DNA-sequencing instrument project.

Many projects fail because of unclear requirements and expectations, so starting with a project charter makes a lot of sense. If project managers are having difficulty obtaining support from project stakeholders, for example, they can refer to the agreements listed in the project charter. Note that the sample project charter in Table 1 includes several items under the Approach section to help Nick in managing the project and the sponsor in overseeing it. To help Nick make the transition to project manager, the charter said that the company would hire a technical replacement and part-time assistant for Nick as soon as possible. To help Ahmed, the project sponsor, feel more comfortable with how the project was being managed, items were included to ensure proper planning and communications. Recall from Section 2 that executive support contributes the most to successful IT projects. Because Nick was the fourth project manager on this project, top management at his company obviously had problems choosing and working with project managers.

==========

Table 1 Project charter for the DNA-sequencing instrument completion project

Project Title: DNA-Sequencing Instrument Completion Project

Date of Authorization: February 1

Project Start Date: February 1 Projected Finish Date: November 1

Key Schedule Milestones:

• Complete first version of the software by June 1

• Complete production version of the software by November 1

Budget Information: The firm has allocated $1.5 million for this project, and more funds are available if needed. The majority of costs for this project will be internal labor. All hardware will be outsourced.

Project Manager: Nick Carson, (650) 949-0707, ncarson@dnaconsulting.com

Project Objectives: The DNA-sequencing instrument project has been under way for three years. It is a crucial project for our company. This is the first charter for the project; the objective is to complete the first version of the instrument software in four months and a production version in nine months.

Main Project Success Criteria: The software must meet all written specifications, be thoroughly tested, and be completed on time. The CEO will formally approve the project with advice from other key stakeholders.

Approach:

• Hire a technical replacement for Nick Carson and a part-time assistant as soon as possible.

• Within one month, develop a clear work breakdown structure, scope statement, and Gantt chart detailing the work required to complete the DNA-sequencing instrument.

• Purchase all required hardware upgrades within two months.

• Hold weekly progress review meetings with the core project team and the sponsor.

• Conduct thorough software testing per the approved test plans.

ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES

Name Role Position Contact Information

==========

Taking the time to discuss, develop, and sign off on a simple project charter could have prevented several problems in this case.

After creating a project charter, the next step in project integration management is preparing a project management plan.

DEVELOPING A PROJECT MANAGEMENT PLAN

To coordinate and integrate information across project management knowledge areas and across the organization, there must be a good project management plan. A project management plan is a document used to coordinate all project planning documents and help guide a project's execution and control. Plans created in the other knowledge areas are considered subsidiary parts of the overall project management plan. Project management plans also document project planning assumptions and decisions regarding choices, facilitate communication among stakeholders, define the content, extent, and timing of key management reviews, and provide a baseline for progress measurement and project control. Project management plans should be dynamic, flexible, and subject to change when the environment or project changes. These plans should greatly assist the project manager in leading the project team and assessing project status.

To create and assemble a good project management plan, the project manager must practice the art of project integration management, because information is required from all of the project management knowledge areas. Working with the project team and other stakeholders to create a project management plan will help the project manager guide the project's execution and understand the overall project. The main inputs for developing a project management plan include the project charter, outputs from planning processes, enterprise environment factors, and organizational process assets. The main tool and technique is expert judgment, and the output is a project management plan.

Project Management Plan Contents

Just as projects are unique, so are project management plans. A small project that involves a few people working over a couple of months might have a project management plan consisting of only a project charter, scope statement, and Gantt chart. A large project that involves 100 people working over three years would have a much more detailed project management plan. It is important to tailor project management plans to fit the needs of specific projects. The project management plans should guide the work, so they should be only as detailed as needed for each project.

However, most project management plans have common elements. A project management plan includes an introduction or overview of the project, a description of how the project is organized, the management and technical processes used on the project, and sections describing the work to be performed, the schedule, and the budget.

The introduction or overview of the project should include the following information at a minimum:

• The project name: Every project should have a unique name, which helps distinguish each project and avoids confusion among related projects.

• A brief description of the project and the need it addresses: This description should clearly outline the goals of the project and reason for it.

The description should be written in layperson's terms, avoid technical jargon, and include a rough time and cost estimate.

• The sponsor's name: Every project needs a sponsor. Include the name, title, and contact information of the sponsor in the introduction.

• The names of the project manager and key team members: The project man ager should always be the contact for project information. Depending on the size and nature of the project, names of key team members may also be included.

• Deliverables of the project: This section should briefly list and describe the products that will be created as part of the project. Software packages, pieces of hardware, technical reports, and training materials are examples of deliverables.

• A list of important reference materials: Many projects have a history that precedes them. Listing important documents or meetings related to a project helps project stakeholders understand that history. This section should reference the plans produced for other knowledge areas. Recall from Section 3 that every knowledge area includes some planning processes. Therefore, the project management plan should reference and summarize important parts of the scope management, schedule management, cost management, quality management, human resource management, communications management, risk management, procurement management, and stakeholder management plans.

• A list of definitions and acronyms, if appropriate: Many projects, especially IT projects, involve terminology that is unique to a particular industry or technology. Providing a list of definitions and acronyms will help avoid confusion.

The description of how the project is organized should include the following information:

• Organizational charts: The description should include an organizational chart for the company sponsoring the project and for the customer's company, if the project is for an external customer. The description should also include a project organizational chart to show the lines of authority, responsibilities, and communication for the project. For example, the Manhattan Project introduced in Section 1 had a very detailed organizational chart of all participants.

• Project responsibilities: This section of the project plan should describe the major project functions and activities and identify the people responsible for them. A responsibility assignment matrix (described in Section 9) is often used to display this information.

• Other organizational or process-related information: Depending on the nature of the project, the team might need to document major processes they follow on the project. For example, if the project involves releasing a major software upgrade, team members might benefit from having a diagram or timeline of the major steps involved in the process.

The section of the project management plan that describes management and technical approaches should include the following information:

• Management objectives: It is important to understand top management's view of the project, the priorities for the project, and any major assumptions or constraints.

• Project controls: This section describes how to monitor project progress and handle changes. Will there be monthly status reviews and quarterly progress reviews? Will there be specific forms or charts to monitor progress? Will the project use earned value management (described in Section 7) to assess and track performance? What is the process for change control? What level of management is required to approve different types of changes? (You will learn more about change control later in this section.)

• Risk management: This section briefly addresses how the project team will identify, manage, and control risks. This section should refer to the risk management plan, if one is required for the project.

• Project staffing: This section describes the number and types of people required for the project. It should refer to the human resource plan, if one is required for the project.

• Technical processes: This section describes specific methodologies a project might use and explains how to document information. For example, many IT projects follow specific software development methodologies or use particular Computer Aided Software Engineering (CASE) tools. Many companies or customers also have specific formats for technical documentation. It is important to clarify these technical processes in the project management plan.

The next section of the project management plan should describe the work needed to perform and reference the scope management plan. It should summarize the following:

• Major work packages: A project manager usually organizes the project work into several work packages using a work breakdown structure (WBS), and produces a scope statement to describe the work in more detail. This section should briefly summarize the main work packages for the project and refer to appropriate sections of the scope management plan.

• Key deliverables: This section lists and describes the key products created as part of the project. It should also describe the quality expectations for the product deliverables.

• Other work-related information: This section highlights key information related to the work performed on the project. For example, it might list specific hardware or software to use on the project or certain specifications to follow. It should document major assumptions made in defining the project work.

The project schedule information section should include the following:

• Summary schedule: It is helpful to have a one-page summary of the overall project schedule. Depending on the project's size and complexity, the summary schedule might list only key deliverables and their planned completion dates. For smaller projects, it might include all of the work and associated dates for the entire project in a Gantt chart. For example, the Gantt chart and milestone schedule provided in Section 3 for JWD Consulting were fairly short and simple.

• Detailed schedule: This section provides more detailed information about the project schedule. It should reference the schedule management plan and discuss dependencies among project activities that could affect the project schedule. For example, this section might explain that a major part of the work cannot start until an external agency provides funding. A network diagram can show these dependencies (see Section 6, Project Time Management).

• Other schedule-related information: Many assumptions are often made when preparing project schedules. This section should document major assumptions and highlight other important information related to the project schedule.

The budget section of the project management plan should include the following:

• Summary budget: The summary budget includes the total estimate of the overall project's budget. It could also include the budget estimate for each month or year by certain budget categories. It is important to provide some explanation of what these numbers mean. For example, is the total budget estimate a firm number that cannot change, or is it a rough estimate based on projected costs over the next three years?

• Detailed budget: This section summarizes the contents of the cost management plan and includes more detailed budget information. For example, what are the fixed and recurring cost estimates for the project each year? What are the projected financial benefits of the project? What types of people are needed to do the work, and how are the labor costs calculated? (See Section 7, Project Cost Management, for more information on creating cost estimates and budgets.)

• Other budget-related information: This section documents major assumptions and highlights other important information related to financial aspects of the project.

Using Guidelines to Create Project Management Plans

Many organizations use guidelines to create project management plans. Microsoft Project and other project management software packages come with several template files to use as guidelines. However, do not confuse a project management plan with a Gantt chart. The project management plan is much more than a Gantt chart, as described earlier.

Many government agencies also provide guidelines for creating project management plans. For example, the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) Standard 2167, Software Development Plan, describes the format for contractors to use when creating a software development plan for DOD projects. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) Standard 1058-1998 describes the contents of its Software Project Management Plan (SPMP). Table 2 provides some of the categories for the IEEE SPMP. Companies that work on software development projects for the Department of Defense must follow this standard or a similar standard. See the companion Web site for links to samples of project management plans or search various government Web sites to find free, detailed examples.

------------

Table 2 Sample contents for a software project management plan (SPMP)

Major Section Headings Section Topics

Overview Purpose, scope, and objectives; assumptions and constraints; project deliverables; schedule and budget summary; evolution of the plan Project Organization External interfaces; internal structure; roles and responsibilities Managerial Process Plan Start-up plans (estimation, staffing, resource acquisition, and project staff training plans); work plan (work activities, schedule, resource, and budget allocation); control plan; risk management plan; closeout plan Technical Process Plans Process model; methods, tools, and techniques; infrastructure plan; product acceptance plan Supporting Process Plans Configuration management plan; verification and validation plan; documentation plan; quality assurance plan; reviews and audits; problem resolution plan; subcontractor management plan; process improvement plan

-------------

In many private organizations, specific documentation standards are not as rigorous; however, there are usually guidelines for developing project management plans. It is good practice to follow the organization's standards or guidelines for developing project management plans to facilitate their execution. The organization can work more efficiently if all project management plans follow a similar format. Recall from Section 1 that companies that excel in project management develop and deploy standardized project delivery systems.

The winners clearly spell out what needs to be done in a project, by whom, when, and how. For this they use an integrated toolbox, including PM tools, methods, and techniques. … If a scheduling template is developed and used over and over, it becomes a repeatable action that leads to higher productivity and lower uncertainty. Sure, using scheduling templates is neither a breakthrough nor a feat. But laggards exhibited almost no use of the templates. Rather, in constructing schedules their project man agers started with a clean sheet, a clear waste of time.

For example, in the section's opening case, Nick Carson's top managers were disappointed because he did not provide the project planning information they needed to make important business decisions. They wanted to see detailed project management plans, including schedules and a means for tracking progress. Nick had never created a project management plan or even a simple progress report before, and the organization did not provide templates or examples to follow. If it had, Nick might have been able to deliver the information top management was expecting.

DIRECTING AND MANAGING PROJECT WORK

Directing and managing project work involves managing and performing the work described in the project management plan, one of the main inputs for this process.

Other inputs include approved change requests, enterprise environmental factors, and organizational process assets. The majority of time on a project is usually spent on execution, as is most of the project's budget. The application area of the project directly affects project execution because products are created during the execution phase. For example, the DNA-sequencing instrument from the opening case and all associated soft ware and documentation would be produced during project execution. The project team would need to use its expertise in biology, hardware and software development, and testing to create the product successfully.

The project manager would also need to focus on leading the project team and managing stakeholder relationships to execute the project management plan success fully. Project human resource management, communications management, and stake holder management are crucial to a project's success. See Sections 9, 10, and 13, respectively, for more information on these knowledge areas. If the project involves a significant amount of risk or outside resources, the project manager also needs to be well versed in project risk management and project procurement management. See Sections 11 and 12 for details on those knowledge areas. Many unique situations occur during project execution, so project managers must be flexible and creative in dealing with them. Review the situation that Erica Bell faced during project execution in Section 3. Also review the ResNet case study (available on the companion Web site for this text) to understand the execution challenges that project manager Peeter Kivestu and his project team faced.

Coordinating Planning and Execution

In project integration management, project planning and execution are intertwined and inseparable activities. The main function of creating a project management plan is to guide project execution. A good plan should help produce good products or work results, and should document what constitutes good work results. Updates to plans should reflect knowledge gained from completing work earlier in the project. Anyone who has tried to write a computer program from poor specifications appreciates the importance of a good plan. Anyone who has had to document a poorly programmed system appreciates the importance of good execution.

A common-sense approach to improving the coordination between project plan development and execution is to follow this simple rule: Those who will do the work should plan the work. All project personnel need to develop both planning and executing skills, and they need experience in these areas. In IT projects, programmers who have to write detailed specifications and then create the code from them become better at writing specifications. Likewise, most systems analysts begin their careers as programmers, so they understand what type of analysis and documentation they need to write good code.

Although project managers are responsible for developing the overall project management plan, they must solicit input from project team members who are developing plans in each knowledge area.

Providing Strong Leadership and a Supportive Culture

Strong leadership and a supportive organizational culture are crucial during project execution. Project managers must lead by example to demonstrate the importance of creating good project plans and then following them in project execution. Project managers often create plans for things they need to do themselves. If project managers follow through on their own plans, their team members are more likely to do the same.

Good project execution also requires a supportive organizational culture. For example, organizational procedures can help or hinder project execution. If an organization has useful guidelines and templates for project management that everyone in the organization follows, it will be easier for project managers and their teams to plan and do their work. If the organization uses the project plans as the basis for performing work and monitoring progress during execution, the culture will promote the relationship between good planning and execution. On the other hand, if organizations have confusing or bureaucratic project management guidelines that hinder getting work done or measuring progress against plans, project managers and their teams will be frustrated.

Even with a supportive organizational culture, project managers may sometimes find it necessary to break the rules to produce project results in a timely manner. When project managers break the rules, politics will play a role in the results. For example, if a particular project requires use of nonstandard software, the project manager must use political skills to convince concerned stakeholders that using standard software would be inadequate. Breaking organizational rules-and getting away with it-requires excellent leader ship, communication, and political skills.

Capitalizing on Product, Business, and Application Area Knowledge

In addition to strong leadership, communication, and political skills, project managers need to possess product, business, and application area knowledge to execute projects successfully. It is often helpful for IT project managers to have prior technical experience or at least a working knowledge of IT products. For example, if the project manager were leading a Joint Application Design (JAD) team to help define user requirements, it would be helpful to understand the language of the business and technical experts on the team.

See Section 5, Project Scope Management, for more information on JAD and other methods for collecting requirements.

Many IT projects are small, so project managers may be required to perform some technical work or mentor team members to complete the project. For example, a three month project to develop a Web-based application with only three team members would benefit most from a project manager who can complete some of the technical work. On larger projects, however, the project manager's primary responsibility is to lead the team and communicate with key project stakeholders. The project manager does not have time to do the technical work. In this case, it is usually best that the project manager under stand the business and application area of the project more than the technology involved.

However, on very large projects the project manager must understand the business and application area of the project. For example, Northwest Airlines completed a series of projects in recent years to develop and upgrade its reservation systems. The company spent millions of dollars and had more than 70 full-time people working on the projects at peak periods. The project manager, Peeter Kivestu, had never worked in an IT department, but he had extensive knowledge of the airline industry and the reservations process. He carefully picked his team leaders, making sure they had the required technical and product knowledge. ResNet was the first large IT project at Northwest Airlines led by a business manager instead of a technical expert, and it was a roaring success. Many organizations have found that large IT projects require experienced general managers who understand the business and application area of the technology, not the technology itself. (You can find the entire ResNet case study on the companion Web site for this text.)

Project Execution Tools and Techniques

Directing and managing project work requires specialized tools and techniques, some of which are unique to project management. Project managers can use specific tools and techniques to perform activities that are part of execution processes. These include:

• Expert judgment: Anyone who has worked on a large, complex project appreciates the importance of expert judgment in making good decisions.

Project managers should not hesitate to consult experts on different topics, such as what methodology to follow, what programming language to use, and what training approach to follow.

• Meetings: Meetings are crucial during project execution. Face-to-face meetings with individuals or groups of people are important, as are phone and virtual meetings. Meetings allow people to develop relationships, pick up on important body language or tone of voice, and have a dialogue to help resolve problems. It is often helpful to establish set meeting times for various stake holders. For example, Nick could have scheduled a short meeting once a week with senior managers. He could have also scheduled 10-minute stand-up meetings every morning for the project team.

• Project management information systems: As described in Section 1, hundreds of project management software products are on the market today.

Many large organizations use powerful enterprise project management systems that are accessible via the Internet and tie into other systems, such as financial systems. Even in smaller organizations, project managers or other team members can create Gantt charts that include links to other planning documents on an internal network. For example, Nick or his assistant could have created a detailed Gantt chart for their project in Project 2010 and created links to other key planning documents created in Word, Excel, or PowerPoint. Nick could have shown the summary tasks during the progress review meetings, and if top management had questions, Nick could have shown them supporting details. Nick's team could also have set baselines for completing the project and tracked their progress toward achieving those goals. See section A for details on using MS Project to perform these functions, and for samples of Gantt charts and other useful outputs from project management software.

Although project management information systems can aid in project execution, project managers must remember that positive leadership and strong teamwork are critical to successful project management. Project managers should delegate the detailed work involved in using these tools to other team members and focus on providing leadership for the whole project to ensure project success. Stakeholders often focus on the most important output of execution from their perspective: the deliverables. For example, a production version of the DNA-sequencing instrument was the main deliverable for the project in the opening case. Of course, many other deliverables were created along the way, such as software modules, tests, and reports. Other outputs of project execution include work performance information, change requests, and updates to the project management plan and project documents.

===========

WHAT WENT RIGHT?

Malaysia's capital, Kuala Lumpur, has become one of Asia's busiest, most exciting cities.

With growth, however, came traffic. To help alleviate this problem, the city hired a local firm in 2003 to manage a multimillion-dollar project to develop a state-of-the-art Integrated Transport Information System (ITIS). The Deputy Project Director, Lawrence Liew, explained that team members broke the project into four key phases and focused on several key milestones. They deliberately kept the work loosely structured to allow the team to be more flexible and creative in handling uncertainties. They based the entire project team within a single project office to streamline communications and facilitate quick problem solving through ad hoc working groups. They also used a dedicated project intranet to exchange information between the project team and subcontractors.

The project was completed in 2005, and ITIS continues to improve traffic flow into Kuala Lumpur.

==============

The system now provides video streaming of traffic information on cell phones as well as other important transportation information. For more recent information on ITIS, visit its Web site at:

itis.com.my/atis.

Project managers and their teams are most often remembered for how well they executed a project and handled difficult situations. Likewise, sports teams around the world know that the key to winning is good execution. Team coaches can be viewed as project managers, with each game a separate project. Coaches are often judged on their win-loss record, not on how well they planned for each game. On a humorous note, when one losing coach was asked what he thought about his team's execution, he responded, "I'm all for it!"

MONITORING AND CONTROLLING PROJECT WORK

On large projects, many project managers say that 90 percent of the job is communicating and managing changes. Changes are inevitable on most projects, so it's important to develop and follow a process to monitor and control changes.

Monitoring project work includes collecting, measuring, and disseminating performance information. It also involves assessing measurements and analyzing trends to determine what process improvements can be made. The project team should continuously monitor project performance to assess the overall health of the project and identify areas that require special attention.

The project management plan, schedule and cost forecasts, validated changes, work performance information, enterprise environmental factors, and organizational process assets are all important inputs for monitoring and controlling project work.

The project management plan provides the baseline for identifying and controlling project changes. A baseline is the approved project management plan plus approved changes. For example, the project management plan includes a section that describes the work to perform on a project. This section of the plan describes the key deliverables for the project, the products of the project, and quality requirements. The schedule section of the project management plan lists the planned dates for completing key deliverables, and the budget section of the plan provides the planned cost of these deliverables. The project team must focus on delivering the work as planned. If the project team or some one else causes changes during project execution, the team must revise the project management plan and have it approved by the project sponsor. Many people refer to different types of baselines, such as a cost baseline or schedule baseline, to describe different project goals more clearly and performance toward meeting them.

Schedule and cost forecasts, validated changes, and work performance information provide details on how project execution is going. The main purpose of this information is to alert the project manager and project team about issues that are causing problems or might cause problems in the future. The project manager and project team must continuously monitor and control project work to decide if corrective or preventive actions are needed, what the best course of action is, and when to act.

==========

MEDIA EXAMPLE

Few events get more media attention than the Olympic Games. Imagine all the work involved in planning and executing an event that involves thousands of athletes from around the world with millions of spectators. The 2002 Olympic Winter Games and Paralympics took five years to plan and cost more than $1.9 billion. PMI presented the Salt Lake Organizing Committee (SLOC) with the Project of the Year award for delivering world-class games that, according to the International Olympic Committee, "made a pro found impact upon the people of the world."12 Four years before the Games began, the SLOC used a Primavera software-based sys tem with a cascading color-coded WBS to integrate planning. A year before the Games, the team added a Venue Integrated Planning Schedule to help integrate resource needs, budgets, and plans. For example, this software helped the team coordinate different areas involved in controlling access into and around a venue, such as roads, pedestrian path ways, seating and safety provisions, and hospitality areas, saving nearly $10 million.

When the team experienced a budget deficit three years before the Games, it separated "must-have" items from "nice-to-have" items and implemented a rigorous expense approval process. According to Matthew Lehman, SLOC managing director, using classic project management tools turned a $400 million deficit into a $100 million surplus.

The SLOC also used an Executive Roadmap, a one-page list of the top 100 activities during the Games, to keep executives apprised of progress. Activities were tied to detailed project information within each department's schedule. A 90-day highlighter showed which managers were accountable for each integrated activity. Fraser Bullock, SLOC Chief Operating Officer and Chief, said, "We knew when we were on and off schedule and where we had to apply additional resources. The interrelation of the functions meant they could not run in isolation-it was a smoothly running machine.

=======

Important outputs of monitoring and controlling project work include change requests and work performance reports. Change requests include recommended corrective and preventive actions and defect repairs. Corrective actions should result in improvements in project performance. Preventive actions reduce the probability of negative consequences associated with project risks. Defect repairs involve bringing defective deliverables into conformance with requirements. For example, if project team members have not been reporting hours that they worked, a corrective action would show them how to enter the information and let them know that they need to do it. An example of a preventive action might be modifying a time-tracking system screen to avoid common errors people made in the past. A defect repair might be having someone redo an incorrect entry. Many organizations use a formal change request process and forms to keep track of project changes, as described in the next section. Work performance reports include status reports, progress reports, memos, and other documents used to communicate performance.