What Has the Euro Done for Its Members?

Supporters of the euro point to its enormous symbolic importance. In light of the many past wars among European countries, what better proof of the permanent end to conflict than the adoption of a common currency? They also point to the economic advantages of having a common currency: no more changes in exchange rates for European firms to worry about; no more need to change currencies when crossing borders. Together with the removal of other obstacles to trade among European countries, the euro contributes, they argue, to the creation of a large economic power in the world. There is little question that the move to the euro was indeed one of the main economic events of the start of the twenty-first century.

Others worry, however, that the symbolism of the euro has come with substantial economic costs. Even before the crisis, they pointed out that a common currency means a common monetary policy, which means the same interest rate across the euro countries. What if, they argued, one country plunges into recession while another is in the middle of an economic boom? The first country needs lower interest rates to increase spending and output; the second country needs higher interest rates to slow down its economy. If interest rates have to be the same in both countries, what will happen? Isn't there the risk that one country will remain in recession for a long time or that the other will not be able to slow down its booming economy? And a common currency also means the loss of the exchange rate as an instrument of adjustment within the Euro area. What if, they argued, a country has a large trade deficit and needs to become more competitive? If it cannot adjust its exchange rate, it must adjust by decreasing prices relative to its competitors. This is likely to be a painful and long process.

Until the Euro crisis, the debate had remained somewhat abstract. It no longer is. As a result of the crisis, a number of Euro members, from Ireland and Portugal, to Greece, have gone through deep recessions. If they had their own currency, they could have depreciated their currency vis-à-vis other Euro members to increase the demand for their exports. Because they shared a currency with their neighbors, this was not possible. Thus, some economists conclude, some countries should drop out of the euro and recover control of their monetary policy and of their exchange rate. Others argue that such an exit would be both unwise because it would give up on the other advantages of being in the euro and be extremely disruptive, leading to even deeper problems for the country that exited. This issue is likely to remain a hot one for some time to come.

The issue is less important when comparing two rich countries. Thus, this was not a major issue when comparing standards of living in the United States and the Euro area previously.

4. China

China is in the news every day. It is increasingly seen as one of the major economic powers in the world. Is the attention justified? A first look at the numbers in FIG. 7 on page 14 suggests it may not be. True, the population of China is enormous, more than four times that of the United States. But its output, expressed in dollars by multiplying the number in yuans (the Chinese currency) by the dollar-yuan exchange rate, is still only 10.4 trillion dollars, about 60% of the United States. Output per person is about $7,600, only roughly 15% of output per person in the United States.

So why is so much attention paid to China? There are two main reasons: To under stand the first, we need to go back to the number for output per person. When comparing output per person in a rich country like the United States and a relatively poor country like China, one must be careful. The reason is that many goods are cheaper in poor countries. For example, the price of an average restaurant meal in New York City is about 20 dollars; the price of an average restaurant meal in Beijing is about 25 yuans, or, at the current exchange rate, about 4 dollars. Put another way, the same income (ex pressed in dollars) buys you much more in Beijing than in New York City. If we want to compare standards of living, we have to correct for these differences; measures which do so are called PPP (for purchasing power parity) measures. Using such a measure, output per person in China is estimated to be about $12,100, roughly one-fourth of the output per person in the United States. This gives a more accurate picture of the standard of living in China. It is obviously still much lower than that of the United States or other rich countries. But it is higher than suggested by the numbers in FIG. 7.

FIG. 7 China, 2014 Source: World Economic Outlook, IMF.

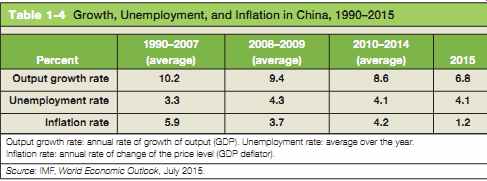

Second, and more importantly, China has been growing very rapidly for more than three decades. This is shown in Table 1-4, which, like the previous tables for the United States and the Euro area, gives output growth, unemployment, and inflation for the periods 1990-2007, 2008-2009, 2010-2014, and the forecast for 2015.

The first line of the table tells the basic story. Since 1990 (indeed, since 1980, if we were to extend the table back by another 10 years), China has grown at close to 10% a year. This represents a doubling of output every 7 years. Compare this number to the numbers for the United States and for Europe we saw previously, and you understand why the weight of the emerging economies in the world economy, China being the main one, is increasing so rapidly.

There are two other interesting aspects to Table 4. The first is how difficult it is to see the effects of the crisis in the data. Growth barely decreased during 2008 and 2009, and unemployment barely increased. The reason is not that China is closed to the rest of the world. Chinese exports slowed during the crisis. But the adverse effect on demand was nearly fully offset by a major fiscal expansion by the Chinese government, with, in particular, a major increase in public investment. The result was sustained growth of demand and, in turn, of output.

The second is the decline in growth rates from 10% before the crisis to less than 9% after the crisis, and to the forecast 6.8% for 2015. This raises questions both about how China maintained such a high growth rate for so long, and whether it is now entering a period of lower growth.

Table 4 Growth, Unemployment, and Inflation in China, 1990-2015.

A preliminary question is whether the numbers are for real. Could it be that Chinese growth was and is still overstated? After all, China is still officially a communist country, and government officials may have incentives to overstate the economic performance of their sector or their province. Economists who have looked at this carefully conclude that this is probably not the case. The statistics are not as reliable as they are in richer countries, but there is no major bias. Output growth is indeed very high in China. So where has growth come from? It has come from two sources: The first was high accumulation of capital. The investment rate (the ratio of investment to output) in China is 48%, a very high number. For comparison, the investment rate in the United States is only 19%. More capital means higher productivity and higher output. The second is rapid technological progress. One of the strategies followed by the Chinese government has been to encourage foreign firms to relocate and produce in China. As foreign firms are typically much more productive than Chinese firms, this has increased productivity and output. Another aspect of the strategy has been to encourage joint ventures between foreign and Chinese firms. By making Chinese firms work with and learn from foreign firms, the productivity of the Chinese firms has increased dramatically.

When described in this way, achieving high productivity and high output growth appears easy and a recipe that every poor country could and should follow. In fact, things are less obvious. China is one of a number of countries that made the transition from central planning to a market economy. Most of the other countries, from Central Europe to Russia and the other former Soviet republics, experienced a large decrease in output at the time of transition. Most still have growth rates far below that of China. In many countries, widespread corruption and poor property rights make firms unwilling to invest. So why has China fared so much better? Some economists believe that this is the result of a slower transition: The first Chinese reforms took place in agriculture as early as 1980, and even today, many firms remain owned by the state. Others argue that the fact that the communist party has remained in control has actually helped the economic transition; tight political control has allowed for a better protection of property rights, at least for new firms, giving them incentives to invest. Getting the answers to these questions, and thus learning what other poor countries can take from the Chinese experience, can clearly make a huge difference, not only for China but for the rest of the world.

At the same time, the recent growth slowdown raises a new set of questions: Where does the slowdown come from? Should the Chinese government try to maintain high growth or accept the lower growth rate? Most economists and, indeed, the Chinese authorities themselves, believe that lower growth is now desirable, that the Chinese people will be better served if the investment rate decreases, allowing more of output to go to consumption. Achieving the transition from investment to consumption is the major challenge facing the Chinese authorities today.

5. Looking Ahead

This concludes our whirlwind world tour. There are many other regions of the world and many other macroeconomic issues we could have looked at:

India, another poor and large country, with a population of 1,270 million people, which, like China, is now growing very fast and becoming a world economic power.

Japan, whose growth performance for the 40 years following World War II was so impressive that it was referred to as an economic miracle, but it has done very poorly in the last two decades. Since a stock market crash in the early 1990s, Japan has been in a prolonged slump, with average output growth under 1% per year.

Latin America, which went from high inflation to low inflation in the 1990s, and then sustained strong growth. Recently however, its growth has slowed, as a result, in part, of a decline in the price of commodities.

Central and Eastern Europe, which shifted from central planning to a market system in the early 1990s. In most countries, the shift was characterized by a sharp decline in output at the start of transition. Some countries, such as Poland, now have high growth rates; others, such as Bulgaria, are still struggling.

Africa, which has suffered decades of economic stagnation, but where, contrary to common perceptions, growth has been high since 2000, averaging 5.5% per year and reflecting growth in most of the countries of the continent.

Tight political control has also allowed for corruption to develop, and corruption can also threaten investment. China is now in the midst of a strong anti-corruption campaign.

There is a limit to how much you can absorb in this first section. Think about the issues to which you have been exposed:

The big issues triggered by the crisis: What caused the crisis? Why did it transmit so fast from the United States to the rest of the world? In retrospect, what could and should have been done to prevent it? Were the monetary and fiscal responses appropriate? Why is the recovery so slow in Europe? How was China able to maintain high growth during the crisis? Can monetary and fiscal policies be used to avoid recessions? How much of an issue is the zero lower bound on interest rates? What are the pros and cons of joining a common currency area such as the Euro area? What measures could be taken in Europe to reduce persistently high unemployment? Why do growth rates differ so much across countries, even over long periods of time? Can other countries emulate China and grow at the same rate? Should China slow down? The purpose of this guide is to give you a way of thinking about these questions. As we develop the tools you need, I shall show you how to use them by returning to these questions and showing you the answers the tools suggest.

Terms:

common currency area, European Union (EU), Euro area

Questions / Problems:

Quiz:

1. Using the information in this section, label each of the following statements true, false, or uncertain. Explain briefly.

a. Output growth was negative in both advanced as well as emerging and developing countries in 2009.

b. World output growth recovered to its prerecession level after 2009.

c. Stock prices around the world fell between 2007 and 2010 and then recovered to their prerecession level.

d. The rate of unemployment in the United Kingdom is much lower than in much of the rest of Europe.

e. China's seemingly high growth rate is a myth; it is a product solely of misleading official statistics.

f. The high rate of unemployment in Europe started when a group of major European countries adopted a common currency.

g. The Federal Reserve lowers interest rates when it wants to avoid recession and raises interest rates when it wants to slow the rate of growth in the economy.

h. Output per person is different in the Euro area, the United States, and China.

i. Interest rates in the United States were at or near zero from 2009 to 2015.

2. Macroeconomic policy in Europe Beware of simplistic answers to complicated macroeconomic questions. Consider each of the following statements and comment on whether there is another side to the story.

a. There is a simple solution to the problem of high European unemployment: Reduce labor market rigidities.

b. What can be wrong about joining forces and adopting a common currency? Adoption of the euro is obviously good for Europe.

3. Chinese economic growth is the outstanding feature of the world economic scene over the past two decades.

a. In 2014, U.S. output was $17.4 trillion, and Chinese output was $10.4 trillion. Suppose that from now on, the output of China grows at an annual rate of 6.5% per year, whereas the output of the United States grows at an annual rate of 2.2% per year. These are the values in each country for the period 2010-2014 as stated in the text. Using these assumptions and a spreadsheet, calculate and plot U.S. and Chinese out put from 2014 over the next 100 years. How many years will it take for China to have a total level of output equal to that of the United States?

b. When China catches up with the United States in total out put, will residents of China have the same standard of living as U.S. residents? Explain.

c. Another term for standard of living is output per person. How has China raised its output per person in the last two decades? Are these methods applicable to the United States?

d. Do you think China's experience in raising its standard of living (output per person) provides a model for developing countries to follow?

4. The rate of growth of output per person was identified as a major issue facing the United States as of the writing of this section. Go to the 2015 Economic Report of the President and find a table titled

"Productivity and Related Data" (Table B-16). You can download this table as an Excel file.

a. Find the column with numbers that describe the level of output per hour worked of all persons in the nonfarm business sector. This value is presented as an index number equal to 100 in 2009. Calculate the percentage increase in output per hour worked from 2009 to 2010. What does that value mean?

b. Now use the spreadsheet to calculate the average percent increase in output per hour worked for the decades 1970- 1979, 1980-1989, 1990-1999, 2000-2009, and 2010-2014. How does productivity growth in the last decade compare to the other decades?

c. You may be able to find a more recent Economic Report of the President. If so, update your estimate of the average growth rate of output per hour worked to include years past 2014. Is there any evidence of an increase in productivity growth?

5. U.S. postwar recessions This question looks at the recessions over the past 40 years.

To work this problem, first obtain quarterly data on U.S. output growth for the period 1960 to the most recent date from the Web site www.bea.gov. Table 1 presents the percent change in real gross domestic product (GDP). This data can be downloaded to a spreadsheet. Plot the quarterly GDP growth rates from 1960:1 to the latest observations. Which, if any, quarters have negative growth? Using the definition of a recession as two or more consecutive quarters of negative growth, answer the following questions.

a. How many recessions has the U.S. economy undergone since 1960, quarter 2?

b. How many quarters has each recession lasted?

c. In terms of length and magnitude, which two recessions have been the most severe?

6. From Problem 5, write down the quarters in which the six traditional recessions started. Find the monthly series in the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED) database for the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate. Retrieve the monthly data series on the unemployment rate for the period 1969 to the end of the data. Make sure all data series are seasonally adjusted.

a. Look at each recession since 1969. What was the unemployment rate in the first month of the first quarter of negative growth? What was the unemployment rate in the last month of the last quarter of negative growth? By how much did the unemployment rate increase?

b. Which recession had the largest increase in the rate of un employment? Begin with the month before the quarter in which output first falls and measure to the highest level of the unemployment rate before the next recession.

Suggested Reading:

The best way to follow current economic events and issues is to read The Economist, a weekly magazine published in England.

The articles in The Economist are well informed, well written, witty, and opinionated. Make sure to read it regularly.

Other stuff:

Where to Find the numbers

Suppose you want to find the numbers for inflation in Germany over the past five years. Fifty years ago, the answer would have been to learn German, find a library with German publications, find the page where inflation numbers were given, write them down, and plot them by hand on a clean sheet of paper. Today, improvements in the collection of data, the development of computers and electronic databases, and access to the Internet make the task much easier. This Super-Section will help you find the numbers you are looking for, be it inflation in Malaysia last year, or consumption in the United States in 1959, or unemployment in Ireland in the 1980s. In most cases, the data can be down loaded to spreadsheets for further treatment.

For a Quick Look at Current Numbers

The best source for the most recent numbers on output, unemployment, inflation, exchange rates, interest rates, and stock prices for a large number of countries is the last four pages of The Economist, published each week (economist.com). The Web site, like many of the Web sites listed throughout the text, contains both information available free to anyone and information available only to subscribers.

A good source for recent numbers about the U.S. economy is National Economic Trends, published monthly by the Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis. (research.stlouisfed.org/datatrends/net/) For More Detail about the U.S. Economy

A convenient database, with numbers often going back to the 1960s, for both the United States and other countries, is the Federal Reserve Economic Database (called FRED), maintained by the Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis. Access is free, and much of the U.S. data used in this guide comes from that database. (research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/) Once a year, the Economic Report of the President, written by the Council of Economic Advisers and published by the U.S. Government Printing Office in Washington, D.C., gives a description of current evolutions, as well as numbers for most major macroeconomic variables, often going back to the 1950s. It contains two parts, a report on the economy, and a set of statistical tables. Both can be found at gpo.gov/erp

A detailed presentation of the most recent numbers for national income accounts is given in the Survey of Current Business, published monthly by the U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis (bea.gov). A user's guide to the statistics published by the Bureau of Economic Analysis is given in the Survey of Current Business, April 1996.

The standard reference for national income accounts is the National Income and Product Accounts of the United States.

Volume 1, 1929-1958, and Volume 2, 1959-1994, are published by the U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis (www.bea.gov).

For data on just about everything, including economic data, a precious source is the Statistical Abstract of the United States, published annually by the U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census.

Numbers for Other Countries

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, OECD for short, located in Paris, France (oecd.org), is an organization that includes most of the rich countries in the world (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States). Together, these countries account for about 70% of the world's output. One strength of the OECD data is that, for many variables, the OECD tries to make the variables comparable across member countries (or tells you when they are not comparable). The OECD issues three useful publications, all available on the OECD site.

The first is the OECD Economic Outlook, published twice a year. In addition to describing current macroeconomic is sues and evolutions, it includes a data Super-Section, with data for many macroeconomic variables. The data typically go back to the 1980s and are reported consistently, both across time and across countries.

The second is the OECD Employment Outlook, published annually. It focuses more specifically on labor-market issues and numbers.

Occasionally, the OECD puts together current and past data, and publishes a set of OECD Historical Statistics in which various years are grouped together.

The main strength of the publications of the International Monetary Fund (IMF for short, located in Washington, D.C.) is that they cover nearly all of the countries of the world. The IMF has 187 member countries and provides data on each of them (www.imf.org).

A particularly useful IMF publication is the World Economic Outlook (WEO for short), which is published twice a year and which describes major economic events in the world and in specific member countries. Selected series associated with the Outlook are available in the WEO database, available on the IMF site (www.imf.org/external/data.htm). Most of the data shown in this section come from this database.

Two other useful publications are the Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR for short), which focuses on financial developments, and the Fiscal Monitor, which focuses on fiscal developments. All three publications are available on the IMF Web site.

The World Bank also maintains a large data base (data.worldbank.org), with a wide set of indicators, from climate change to social protection.

Historical Statistics For long-term historical statistics for the United States, the basic reference is Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970, Parts 1 and 2, published by the U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census.

For long-term historical statistics for several countries, a precious data source is Angus Maddison's Monitoring the World Economy, 1820-1992, Development Centre Studies, OECD, Paris, 1995. This study gives data going back to 1820 for 56 countries. Two even longer and broader sources are The World Economy: A Millenial Perspective, Development Studies, OECD, 2001, and The World Economy: Historical Statistics, Development Studies, OECD 2004, both also by Angus Maddison.

Current Macroeconomic Issues A number of Web sites offer information and commentaries about the macroeconomic issues of the day. In addition to The Economist Web site, the site maintained by Nouriel Roubini (rgemonitor.com) offers an extensive set of links to articles and discussions on macroeconomic issues (by subscription). Another interesting site is vox.eu (voxeu.org), in which economists post blogs on current issues and events.

If you still have not found what you were looking for, a site maintained by Bill Goffe at the State University of New York (SUNY) (www.rfe.org), lists not only many more data sources, but also sources for economic information in general, from working papers, to data, to jokes, to jobs in economics, and to blogs.

And, finally, the site called Gapminder (gapminder.org) has a number of visually striking animated graphs, many of them on issues related to macroeconomics.

Terms:

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)

International Monetary Fund (IMF)

top of page Article Index Home