The Core -- Introduction

The first two sections of this guide introduce you to the issues and the approach of macroeconomics.

Section 1 -- Section 1 takes you on a macroeconomic tour of the world. It starts with a look at the economic crisis that has shaped the world economy since the late 2000s. The tour then stops at each of the world's major economic powers: the United States, the Euro area, and China.

Section 2 -- Section 2 takes you on a tour of the guide. It defines the three central variables of macroeconomics: output, unemployment, and inflation. It then introduces the three time periods around which the guide is organized: the short run, the medium run, and the long run.

[1]

A Tour of the Economic World

What is macroeconomics? The best way to answer is not to give you a formal definition, but rather to take you on an economic tour of the world, to describe both the main economic evolutions and the issues that keep macroeconomists and macroeconomic policy makers awake at night.

At the time of this writing (the fall of 2015), policy makers are sleeping better than they did just a few years ago. In 2008, the world economy entered a major macroeconomic crisis, the deepest since the Great Depression. World output growth, which typically runs at 4 to 5% a year, was actually negative in 2009. Since then, growth has turned positive, and the world economy is slowly recovering. But the crisis has left a number of scars, and some worries remain.

My goal in this section is to give you a sense of these events and of some of the macroeconomic issues confronting different countries today. I shall start with an overview of the crisis, and then focus on the three main economic powers of the world: the United States, the Euro area, and China.

Section 1 looks at the crisis.

Section 2 looks at the United States.

Section 3 looks at the Euro area.

Section 4 looks at China.

Section 5 concludes and looks ahead.

Read this section as you would read an article in a newspaper. Do not worry about the exact meaning of the words or about understanding the arguments in detail: The words will be defined, and the arguments will be developed in later sections. Think of this section as back ground, intended to introduce you to the issues of macroeconomics. If you enjoy reading this section, you will probably enjoy reading this guide. Indeed, once you have read it, come back to this section; see where you stand on the issues, and judge how much progress you have made in your study of macroeconomics.

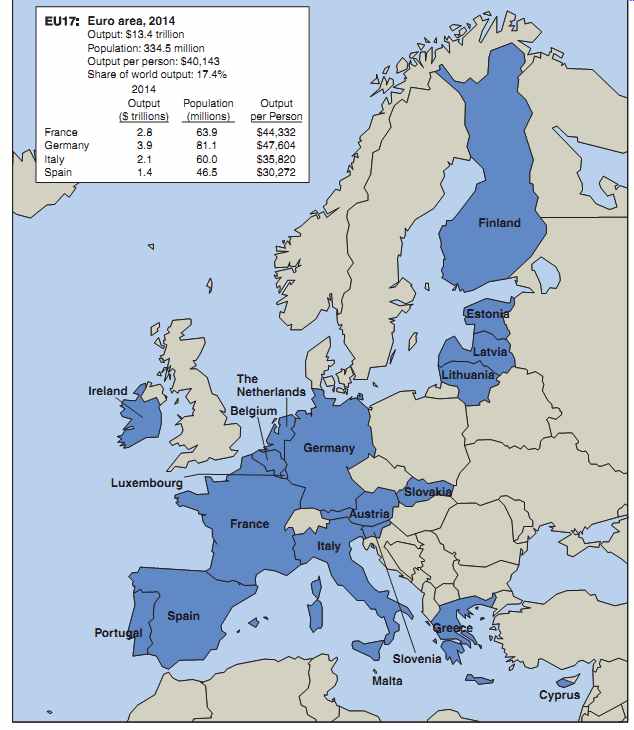

FIG. 1 Output Growth Rates for the World Economy, for Advanced Economies,

and for Emerging and Developing Economies, 2000-2014. Source: World Economic

Outlook Database, July 2015.

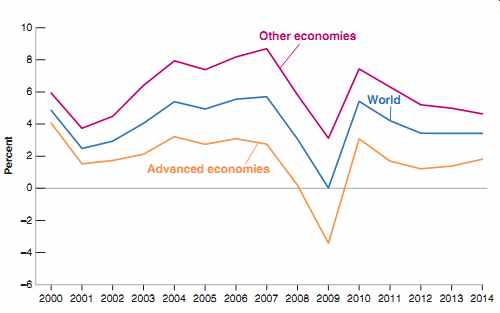

FIG. 2 Stock Prices in the United States, the Euro Area, and Emerging

Economies, 2007-2010

1. The Crisis

FIG. 1 shows output growth rates for the world economy, for advanced economies, and for other economies, separately, since 2000. As you can see, from 2000 to 2007 the world economy had a sustained expansion. Annual average world output growth was 4.5%, with advanced economies (the group of 30 or so richest countries in the world) growing at 2.7% per year, and other economies (the other 150 or so countries in the world) growing at an even faster 6.6% per year.

In 2007 however, signs that the expansion might be coming to an end started to appear. U.S. housing prices, which had doubled since 2000, started declining. Economists started to worry. Optimists believed that, although lower housing prices might lead to lower housing construction and to lower spending by consumers, the Fed (the short name for the U.S. central bank, formally known as the Federal Reserve Board) could lower interest rates to stimulate demand and avoid a recession. Pessimists believed that the decrease in interest rates might not be enough to sustain demand and that the United States may go through a short recession.

Even the pessimists turned out not to be pessimistic enough. As housing prices continued to decline, it became clear that the problems were deeper. Many of the mortgages that had been given out during the previous expansion were of poor quality. Many of the borrowers had taken too large a loan and were increasingly unable to make the monthly payments on their mortgages. And, with declining housing prices, the value of their mortgage often exceeded the price of the house, giving them an incentive to default. This was not the worst of it: The banks that had issued the mortgages had often bundled and packaged them together into new securities and then sold these securities to other banks and investors. These securities had often been repackaged into yet new securities, and so on. The result is that many banks, instead of holding the mortgages themselves, held these securities, which were so complex that their value was nearly impossible to assess.

This complexity and opaqueness turned a housing price decline into a major financial crisis, a development that few economists had anticipated. Not knowing the quality of the assets that other banks had on their balance sheets, banks became reluctant to lend to each other for fear that the bank to which they lent might not be able to repay.

Unable to borrow, and with assets of uncertain value, many banks found themselves in trouble. On September 15, 2008, a major bank, Lehman Brothers, went bankrupt.

The effects were dramatic. Because the links between Lehman and other banks were so opaque, many other banks appeared at risk of going bankrupt as well. For a few weeks, it looked as if the whole financial system might collapse.

This financial crisis quickly turned into a major economic crisis. Stock prices collapsed. FIG. 2 plots the evolution of three stock price indexes, for the United States, for the Euro area, and for emerging economies, from the beginning of 2007 to the end of 2010. The indexes are set equal to 1 in January 2007. Note how, by the end of 2008, stock prices had lost half or more of their value from their previous peak. Note also that, despite the fact that the crisis originated in the United States, European and emerging market stock prices decreased by as much as their U.S. counterparts; I shall return to this later.

Hit by the decrease in housing prices and the collapse in stock prices, and worried that this might be the beginning of another Great Depression, people sharply cut their consumption. Worried about sales and uncertain about the future, firms sharply cut back their investment. With housing prices dropping and many vacant homes on the market, very few new homes were built. Despite strong actions by the Fed, which cut interest rates all the way down to zero, and by the U.S. government, which cut taxes and increased spending, demand decreased, and so did output. In the third quarter of 2008, U.S. output growth turned negative and remained so in 2009.

One might have hoped that the crisis would remain largely contained in the United States. As Figures 1 and 2 both show, this was not the case. The U.S. crisis quickly became a world crisis. Other countries were affected through two channels. The first channel was trade. As U.S. consumers and firms cut spending, part of the decrease fell on imports of foreign goods. Looking at it from the viewpoint of countries exporting to the United States, their exports went down, and so, in turn, did their output. The second channel was financial. U.S. banks, badly needing funds in the United States, repatriated funds from other countries, creating problems for banks in those countries as well. As those banks got in trouble, lending came to a halt, leading to a decrease in spending and in output. Also, in a number of European countries, governments had accumulated high levels of debt and were now running large deficits. Investors began to worry about whether debt could be repaid and asked for much higher interest rates. Confronted with those high interest rates, governments drastically reduced their deficits, through a combination of lower spending and higher taxes. This led in turn to a further decrease in demand, and in output. In Europe, the decline in output was so bad that this particular aspect of the crisis acquired its own name, the Euro Crisis. In short, the U.S. recession turned into a world recession. By 2009, average growth in advanced economies was -3.4%, by far the lowest annual growth rate since the Great Depression. Growth in emerging and developing economies remained positive but was 3.5 percentage points lower than the 2000-2007 average.

Since then, thanks to strong monetary and fiscal policies and to the slow repair of the financial system, most economies have turned around. As you can see from FIG. 1, growth in advanced countries turned positive in 2010 and has remained positive since.

The recovery is however both unimpressive and uneven. In some advanced countries, most notably the United States, unemployment has nearly returned to its pre-crisis level.

The Euro area however is still struggling. Growth is positive, but it is low, and unemployment remains high. Growth in emerging and developing economies has also recovered, but, as you can see from FIG. 1, it is lower than it was before the crisis and has steadily declined since 2010.

Having set the stage, let me now take you on a tour of the three main economic powers in the world, the United States, the Euro area, and China.

2. The United States

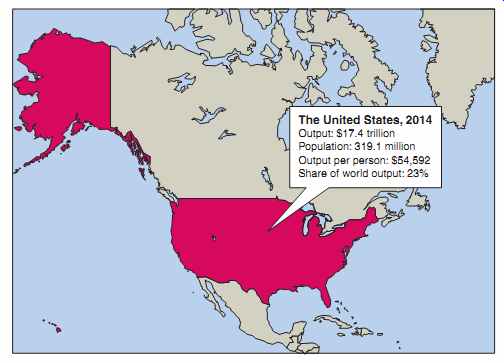

FIG. 3 The United States, 2014 --- The United States, 2014 Output: $17.4

trillion; Population: 319.1 million; Output per person: $54,592; Share

of world output: 23%

When economists look at a country, the first two questions they ask are: How big is the country from an economic point of view? And what is its standard of living? To answer the first, they look at output-the level of production of the country as a whole. To answer the second, they look at output per person. The answers, for the United States, are given in FIG. 3: The United States is big, with an output of $17.4 trillion in 2014, accounting for 23% of world output. This makes it the largest country in the world in economic terms. And the standard of living in the United States is high: Output per person is $54,600. It is not the country with the highest output per person in the world, but it is close to the top.

When economists want to dig deeper and look at the state of health of the country, they look at three basic variables:

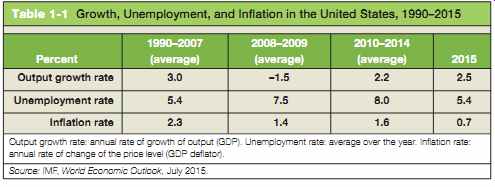

Output growth-the rate of change of output The unemployment rate-the proportion of workers in the economy who are not employed and are looking for a job The inflation rate-the rate at which the average price of goods in the economy is increasing over time Numbers for these three variables for the U.S. economy are given in Table 1. To put current numbers in perspective, the first column gives the average value of each of the three variables for the period 1990 up to 2007, the year before the crisis. The second column shows numbers for the acute part of the crisis, the years 2008 and 2009. The third column shows the numbers from 2010 to 2014, and the last column gives the numbers for 2015 (or more accurately, the forecasts for 2015 as of the fall of 2015).

By looking at the numbers for 2015, you can see why economists are reasonably optimistic about the U.S. economy at this point. Growth in 2015 is forecast to be above 2.5%, just a bit below the 1990-2007 average. Unemployment, which increased during the crisis and its aftermath (it reached 10% during 2010), is decreasing and, at 5.4%, is now back to its 1990-2007 average. Inflation is low, substantially lower than the 1990- 2007 average. In short, the U.S. economy seems to be in decent shape, having largely left the effects of the crisis behind.

Not everything is fine however. To make sure demand was strong enough to sustain growth, the Fed has had to maintain interest rates very low, indeed, too low for comfort.

And productivity growth appears to have slowed, implying mediocre growth in the fu ture. Let's look at both issues in turn.

Table 1 Growth, Unemployment, and Inflation in the United States,

1990-2015

Can you guess some of the countries with a higher standard of living than the United States? Hint: Think of oil producers and financial centers. For answers, look for "Gross Domestic Product per capita, in current prices" at:

imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2015/01/weodata/weoselgr.aspx

Because keeping cash in large sums is inconvenient and

dangerous, people might be willing to hold some bonds even if those pay a small negative interest rate. But there is a clear limit to how negative the interest rate can go before people find ways to switch to cash.

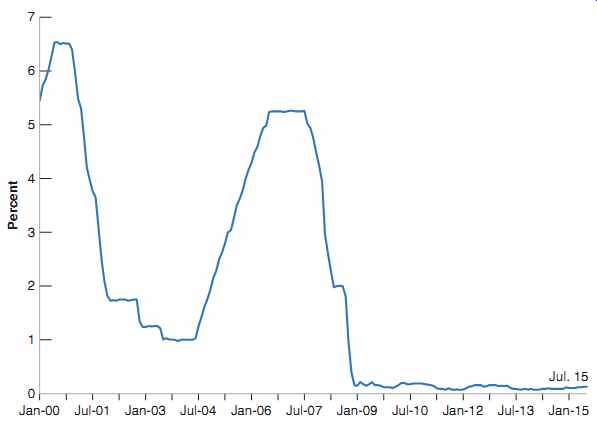

FIG. 4 The U.S. Federal Funds Rate since 2000

As you will see later in the guide, central banks like the Fed can use a few other tools to in crease demand. These tools are known as "unconventional monetary policy." But they do not work as well as the interest rate.

Low Interest Rates and the Zero Lower Bound

When the crisis started, the Fed tried to limit the decrease in spending by decreasing the interest rate it controls, the so-called federal funds rate. As you can see from FIG. 4, on page 8 the federal funds rate went from 5.2% in July 2007 to nearly 0% (0.16% to be precise) in December 2008.

Why did the Fed stop at zero? Because the interest rate cannot be negative. If it were, then nobody would hold bonds, everybody would want to hold cash instead-because cash pays a zero interest rate. This constraint is known in macroeconomics as the zero lower bound, and this is the bound the Fed ran into in December 2008.

This sharp decrease in the interest rate, which made it cheaper for consumers to borrow, and for firms to invest, surely limited the fall in demand and the fall in output.

But, as we saw earlier and you can see from Table 1, this was not enough to avoid a deep recession: U.S. growth was negative in both 2008 and 2009. To help the economy recover, the Fed then kept the interest rate close to zero, where it has remained until now (the fall of 2015). The Fed's plan is to start increasing the interest rate soon, so when you read this guide, it is likely that the rate will have increased, but it will still be very low by historical standards.

Why are low interest rates a potential issue? For two reasons: The first is that low interest rates limit the ability of the Fed to respond to further negative shocks. If the interest rate is at or close to zero, and demand further decreases, there is little the Fed can do to increase demand. The second is that low interest rates appear to lead to excessive risk taking by investors. Because the return from holding bonds is so low, investors are tempted to take too much risk to increase their returns. And too much risk taking can in turn give rise to financial crises of the type we just experienced. Surely, we do not want to experience another crisis like the one we just went through.

How Worrisome Is Low Productivity Growth?

Although the Fed has to worry about maintaining enough demand to achieve growth in the short run, over longer periods of time, growth is determined by other factors, the main one being productivity growth: Without productivity growth, there just cannot be a sustained increase in income per person. And, here, the news is worrisome. Table 1-2 shows average U.S. productivity growth by decade since 1990 for the private sector as a whole and for the manufacturing sector. As you can see, productivity growth in the 2010s has so far been about half as high as it was in the 1990s.

Table 2 Labor Productivity Growth, by Decade

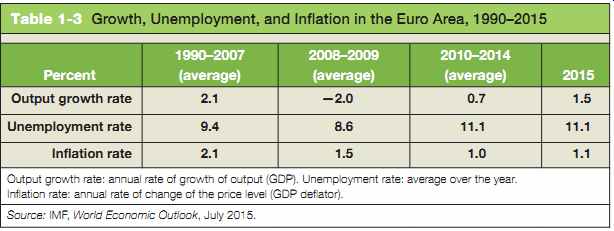

Table 3 Growth, Unemployment, and Inflation in the Euro Area, 1990-2015

How worrisome is this? Productivity growth varies a lot from year to year, and some economists believe that it may just be a few bad years and not much to worry about. Others believe that measurement issues make it difficult to measure output and that productivity growth may be underestimated. For example, how do you measure the real value of a new smartphone relative to an older model? Its price may be higher, but it probably does many things that the older model could not do. Yet others believe that the United States has truly entered a period of lower productivity growth, that the major gains from the current IT innovations may already have been obtained, and that progress is likely to be less rapid, at least for some time.

One particular reason to worry is that this slowdown in productivity growth is happening in the context of growing inequality. When productivity growth is high, most everybody is likely to benefit, even if inequality increases. The poor may benefit less than the rich, but they still see their standard of living increase. This is not the case today in the United States. Since 2000, the real earnings of workers with a high school education or less have actually decreased. If policy makers want to invert this trend, they need either to raise productivity growth or limit the rise of inequality, or both. These are two major challenges facing U.S. policy makers today.

IT stands for information technology.

Until a few years ago, the official name was the European Community, or EC. You may still encounter that name.

The area also goes by the names of "Euro zone" or "Euroland." The first sounds too technocratic, and the second reminds one of Disneyland. I shall avoid them.

3. The Euro Area

In 1957, six European countries decided to form a common European market-an economic zone where people and goods could move freely. Since then, 22 more countries have joined, bringing the total to 28. This group is now known as the European Union, or EU for short.

In 1999, the EU decided to go a step further and started the process of replacing national currencies with one common currency, called the euro. Only 11 countries participated at the start; since then, 8 more have joined. Some countries, in particular, the United Kingdom, have decided not to join, at least for the time being. The official name for the group of member countries is the Euro area. The transition took place in steps. On January 1, 1999, each of the 11 countries fixed the value of its currency to the euro. For example, 1 euro was set equal to 6.56 French francs, to 166 Spanish pesetas, and so on. From 1999 to 2002, prices were quoted both in national currency units and in euros, but the euro was not yet used as currency. This happened in 2002, when euro notes and coins replaced national currencies. Nineteen countries now belong to this common currency area.

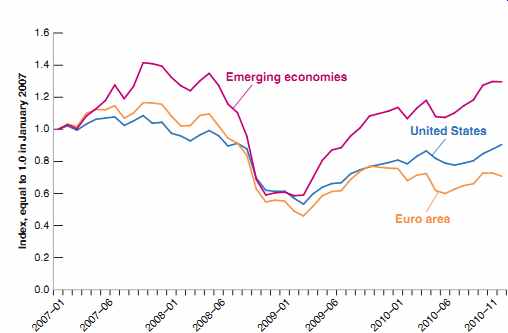

As you can see from FIG. 5, the Euro area is also a strong economic power. Its output is nearly equal to that of the United States, and its standard of living is not far behind. (The EU as a whole has an output that exceeds that of the United States.) As the numbers in Table 1-3 show, however, it is not doing very well.

Just as in the United States, the acute phase of the crisis, 2008 and 2009, was characterized by negative growth. Whereas the United States recovered, growth in the Euro area remained anemic, close to zero over 2010 to 2014 (indeed two of these years again saw negative growth). Even in 2015, growth is forecast to be only 1.5%, less than in the United States, and less than the pre-crisis average. Unemployment, which increased from 2007 on, stands at a high 11.1%, nearly twice that of the United States. Inflation is low, below the target of the European Central Bank, the ECB.

The Euro area faces two main issues today. The first is how to reduce unemployment. Second is whether and how it can function efficiently as a common currency area. We consider these two issues in turn.

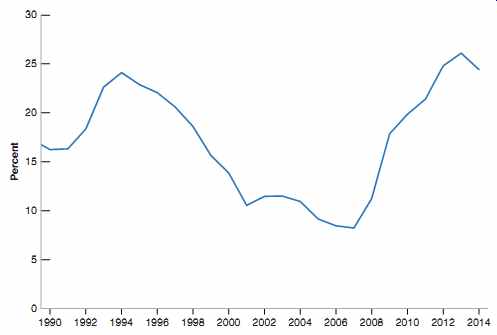

FIG. 6 Unemployment in Spain since 1990

Can European Unemployment Be Reduced?

The high average unemployment rate for the Euro area, 11.1% in 2015, hides a lot of variations across Euro countries. At one end, Greece and Spain have unemployment rates of 25% and 23%, respectively. At the other, Germany's unemployment rate is less than 5%. In the middle are countries like France and Italy, with unemployment rates of 10% and 12%, respectively. Thus, it is clear that how to reduce unemployment must be tailored to the specifics of each country.

To show the complexity of the issues, it is useful to look at a particular country with high unemployment. FIG. 6, on page 12, shows the striking evolution of the Spanish unemployment rate since 1990. After a long boom starting in the mid 1990s, the unemployment rate had decreased from a high of nearly 25% in 1994 to 9% by 2007. But, with the crisis, unemployment exploded again, exceeding 25% in 2013.

Only now, is it starting to decline, but it is still high. The graph suggests two conclusions:

Much of the high unemployment rate today is a result of the crisis, and to the sudden collapse in demand we discussed in the first section. A housing boom turned to housing bust, plus a sudden increase in interest rates, triggered the increase in un employment from 2008 on. One can hope that, eventually, demand will pick up, and unemployment will decrease.

How low can it get? Even at the peak of the boom however, the unemployment rate in Spain was around 9%, nearly twice the unemployment rate in the United States today. This suggests that more is at work than the crisis and the fall in demand. The fact that, for most of the last 20 years, unemployment has exceeded 10% points to problems in the labor market. The challenge is then to identify exactly what these problems are, in Spain, and in other European countries.

Some economists believe the main problem is that European states protect workers too much. To prevent workers from losing their jobs, they make it expensive for firms to lay off workers. One of the unintended results of this policy is to deter firms from hiring workers in the first place, and thus increasing unemployment. Also, to protect workers who become unemployed, European governments provide generous unemployment insurance. But, by doing so, they decrease the incentives for the unemployed to take jobs rapidly; this also increases unemployment. The solution, these economists argue, is to be less protective, to eliminate these labor market rigidities, and to adopt U.S.-style labor market institutions. This is what the United Kingdom has largely done, and its unemployment rate is low.

Others are more skeptical. They point to the fact that unemployment is not high everywhere in Europe. Yet most countries provide protection and generous social insurance to workers. This suggests that the problem may lay not so much with the degree of protection but with the way it is implemented. The challenge, those economists argue, is to understand what the low unemployment countries are doing right, and whether what they do right can be exported to other European countries. Resolving these questions is one of the major tasks facing European macroeconomists and policy makers today.

top of page Article Index Home