The Time Compression Approach -- Customer Focus

Different customer and ultimate end-user needs are satisfied by channels that are capable of delivering different types of service. Different product and market sectors have different service needs. The most appropriate way to meet these needs is through channels that are specifically designed to have distinct logistical capabilities. The alternative is to push everything through the same channel - but the result will be that some customers will be over-served while others are underserved. This will have an adverse effect on costs, customer goodwill and ultimately sustainable profitability. This is all linked with the principle of horizontal boundary definition and is important in channel construction because of the significant impact it can have on the customer.

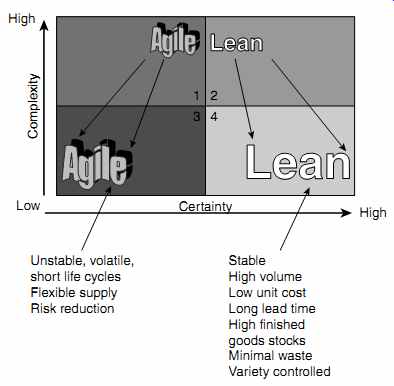

One of the key impacts of the requirement for distinct logistics channels is the need to align them to different types of market and product segment. FIG. 4 illustrates a simplified form of segmentation into four generic supply categories for differing product and market types. The horizontal axis represents levels of demand certainty, with the vertical axis showing levels of product complexity.

Different product types fit into one of the quadrants according to the certainty and complexity criteria.

FIG. 4 Generic supply strategies.

The chart shows that products that have a volatile demand pattern and low constructional complexity will require flexible supply operations to minimize risk. An agile approach is required so that the business process can respond rapidly to new customer requirements in a market that is populated by 'fast follower' competitors enabled by low product complexity. Conversely, products that have more stable and predictable demand are usually in more cost-focused supply situations demanding lower unit costs through tighter management control and probable large economies of scale.

There are therefore two basic supply concepts, one where a business process must be agile, for example a high fashion garment supply chain, and one lean, where a typical example would be commodity-based products such as industrial chemicals. It must be recognized that a range of different products lie between these extremes and may therefore require a mix of both approaches. For example, quadrant 1 would be represented by super-value goods such as the manufacture of aircraft.

These are highly complex items sold into markets with some uncertainty and influenced by fluctuating business cycles and therefore require process agility. Some lean approaches will, however, be required to underpin the longer-horizon investments in a supply market that has the time to evolve and apply competitive pressure. Quadrant 2 is the converse of 1 in that it is characterized by fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG)-type products, which generally sell in more consistent market demand conditions, giving rise to high competition and the need for a lean cost focus. This, however, is mixed with some need for agility in areas linked with product development and innovation.

The various stages of development and evolution of product in terms of its life cycle may cause it to move across segments. The latest FMCG LCD TV has moved from quadrant 1 to quadrant 2 and is progressing towards quadrant 4.

Benefits of Time Compression

There are two categories of time compression benefit. The first is internal time, which has indirect impact on the customer as it relates to the internal consumption of time within a company. The second is external time, which relates to all aspects of time that have direct impact upon the customer, such as lead time from a stock or decoupling point such as a production facility. The net effect of internal time improvements has ramifications on external time-based benefits through cost and service interrelationships.

Internal time benefits in most manufacturing facilities, such as cycle time reductions, give work-in-progress reductions and productivity increases. Stalk and Hout (1990) claim empirically that for every halving of cycle times and doubling of work in process turns, productivity increases by 20 to 70 percent. A halving of manufacturing lead time using the same number of people reduces costs by 50 percent. These changes are reflected in the return on assets where increases of 80 percent are possible. Then 45 percent less cash is required to grow the company at an equable rate.

Generally, the longer the elapsed time in the supply chain, the greater the commercial risk associated with under- or over-forecasting demand.

This results in the use of speculation stock for future customer needs. If, for example, a fashion-associated product has to be ordered from the Far East nine months in advance, then the risk of forecasting error is high. Consequently, the costs associated with potential markdowns are high where significantly large stocks of inventory are held, and in the converse situation where minimal or under-stocking occurs then the opportunity cost of lost sales and goodwill is substantial.

The key point for time compression is that if lead times (cycle times) are compressed, not only is cycle stock (pipeline inventory) reduced, but the period over which forecasting has to be performed reduces - and the shorter the period, the better the forecast accuracy. The better the forecast accuracy, the less demand variance will exist and the less buffer or safety stock is required. Less overall demand for inventory means that less has to be produced and supply processes can respond more promptly. Again, therefore, lead times compress and a virtuous time compression cycle comes into existence.

The internal benefits provide scope to assist the external benefits of a time compression approach. The primary aspect to consider is the con sequence of compressing customer lead times and the opportunity to increase business turnover and possibly prices. Stalk and Hout infer that customers of time-based suppliers are willing to pay more for their products for both subjective and economic reasons:

The customer needs less stock (cycle and buffer stock).

The customer makes decisions to purchase nearer the time of need, therefore reducing risk.

Reduction of cancelled / changed orders, with less time available and less need to change.

Increase in the velocity of cash flow.

The factors influencing risk have an implication on market share. By being faster and more reliable than the competition, market share can be increased. A time-compressed supplier can use its flexible delivery system to supply increased variety to the customer in the form of increased style and / or technological sophistication. If this is delivered with a response advantage, the time-compressed supplier will attract the most profitable customers. Conversely, competitors will be forced to service the customers that are prepared to wait and, as a consequence, be prepared to pay less for the product. Generally, time-compressed suppliers appear to grow at three to four times the rate of their competitors and three times faster than overall demand with twice the level of profitability. When the slower competitor companies do decide to become time based they must do so from the disadvantaged position of having to incur the costs of regaining market share without securing the full benefits.

Experience from TCP has shown that the general price and market share advantage must be considered in the context of the local market and the logistical characteristics of product being supplied. For example, in the UK during the 90s, as the specter of cheaper overseas sources became a reality, time compression enabled companies such as H&R Johnson to optimize its business processes. This enabled it to retain market share against cheap foreign imports of ceramic tile products rather than gaining a specific price advantage. Some price advantage could, however, be applied in time-sensitive market segments such as high-fashion products where process time from design concept to full volume provided a sustainable strategic differentiator over distant competitors.

Demand acquisition approaches such as customer relationship management (CRM) help predict, define and place new customer demands on supplying companies within short time spans. The need to respond to this level of rapidly communicated customer transparency has become the new competitive frontier. Companies that do not adjust their business processes fast enough will quickly lose ground to the competition. Agility coupled with lean is key, with a focus on the use of time compression as an enabler of process delivery and reinvention.

Examples of the Application of Time Compression

Many companies in the United States, Japan and Europe use a time compression approach either as an open policy or as something philosophically buried within the strategic mix (Stalk and Webber, 1993). Table 5.2 illustrates the nature of, and results from, a number of TCP projects.

=========

Table 2 Results from a sample of TCP projects

[ Company

H&R Johnson Massey Ferguson British Airways

Fairey Hydraulics GKN Hardy Spicer CV Knitwear

]

[ Scope of the project

Customer lea times

Process time

Warehouse ink removed Component arrears

Inbound logistics

Time to develop product

]

[ Compression achieved

Two weeks to two days

Reduced by 20%

Two days' compression 50% reduction

Reduced by 85%

Reduced by 50%

]

[

Strategic significance of the improvement

To counter competitive import products and retain a strategic segment of the market To reduce cost of inventory by compressing cycle times via a manufacturing cell To maximize on aircraft flying hours, reduce inventory costs and increase asset utilization by moving into a contract market Retain market share and reduce inventory costs Reduce raw material and operating costs to maintain competitiveness To meet the customer's time based requirement for an increased number of ranges each year. Customer retained

]

==========

Time compression of a global supply chain

The following case study has been compiled from a number of projects to demonstrate a diverse range of applications within one example. Use of this hybrid hypothetical example has also enabled demonstration of some world-class solution examples while maintaining confidentiality.

The case study demonstrates the application of a combination of time compression strategies focused on the attainment of a number of the supply chain principles in a global context. The principles addressed are underlined and the various strategies are denoted in italics. The example takes one of the big Western retailers and an aspect of its global supply chain involved with sourcing product from a major low-cost manufacturing nation.

Two categories of product will be considered, defined by their market and product segmentation relating to the four generic supply strategies above. The first is a product group that has stable demand but a low margin, due in part to intense competition. This might be, for example, wall fixings such as screws and nails, and would require a lean supply chain concept capitalizing on the stable product demand, thereby under pinning a low-cost solution. In contrast, a fashion product category such as women's skirts has less stable demand, with more scope to attain higher margins as competition from exact product replicas or substitutes is more limited within the initial short sales launch time frame. To cope with the higher demand variability and volatility, the fashion product supply chain must have the ability to react to change via fast product replenishment or product reinvention. The supply chain has to be agile rather than lean, with emphasis on risk mitigation via resource deployment rather than a pure cost minimization approach.

This form of product categorization enables constructive supply chain design (or re-engineering) based on the end-user focus which in these examples is highlighted by the need for different levels of flexibility and cost attainment. These 'end-user' demands translate into logistical requirements which can be met by specific logistic (horizontal) channel design specifications. One key aspect of the design specification of any channel is the inventory positioning and this will depend on supply and demand variability coupled with lead times. These factors will give rise to appropriate types or forms of inventory being held in specific quantities at strategic locations within the channel. An example for the agile channel might include the need for inventory to be held close to the retailer but in semi-finished form, thereby postponing final product assembly, at a location a short distance, and therefore with a short period of risk expo sure, from the market. Products designed using standardized components and modules lend themselves well to postponement.

The majority of supply chains are under the ownership of different legal entities, such as companies, and also under the influence of different organizations, such as departments and employees. These entities legally and organizationally interact with each other and create areas of focus and specialization along the supply chain at the same time as creating constraints and check points (e.g. for quality or variance control) at the various interfaces (vertical boundaries). The optimal operation of any channel is strongly influenced by the position of these vertical boundaries and the influence that they exert on the supply chain. These boundaries must therefore be designed and negotiated into the channel in line with the application of concepts such as make / buy decision theory, best practice outsourcing and the idea of organizational process design. In our two channel example the question of who should own the inventory is one key aspect of this issue. Often the weakest channel partner is left with the cost of ownership; however, in the agile or lean supply chain the suppliers may, for example, own the inventory in the retail store. This might be for good logical reasons of control and focus in a retail environment that has to merchandise and replenish thousands of other diverse product lines.

Ownership of either the inventory, process or the company entity is a major influence, hence the focus on conflict resolution in supply chains with aspirations to use partnership and empowerment approaches. At a more generic level some form of cooperation and coordination will always be required between the various forms of interface along the supply chain. System-based exchange of information and data has transformed the way supply chains can operate and has expanded the scope of what can be achieved between the interfaces. For example, systems (generically a form of automation) allow for the rapid transfer of data globally along supply chains. For practical purposes this is usually instantaneous (concurrent working) and integrated in that interconnecting process links are available, compatible and can respond. In our agile channel example, retail sales information can be made available to the supplier on the other side of the world. They are motivated and can respond accordingly and for example be in a position to authorize and generate replenishment orders on behalf of the retailer. This form of linkage alleviates the effects of demand dynamics where time delays in the supply of information along the chain creates uncertainty, causing sup pliers to mitigate against risk using standby resources and processes that are non-value-adding and result in unnecessary costs.

The final aspect of this example considers the inbound flow of materials to support the manufacturing operations. There is a natural tendency to focus on the parts of the supply chain that directly affect customers to the exclusion of the inbound supply chain. Vendor management initiatives and carefully considered inventory ownership policies often provide the desired focus on this sometimes neglected area. However, scope often exists to investigate and map the entire inbound supply chain and consolidate into appropriate horizontal channels and to simplify the types of flows using a unified approach for handling raw materials that have logistically distinct characteristics. In the example of fixings, supply of metal rods, chemicals and other materials all arrived at the factory via a range of different channels -- some via direct delivery via a carrier network, others supplied in bulk to the factory warehouse, some supplied from a vendor regional warehouse or a combination of all three types of supply via a range of providers. An equal level of complexity and variety existed to support the range of information flows and communications.

Typically these supply arrangements and associated communication complexities arise for historical reasons and establish themselves over a period of time.

The inbound supply chain operated and sustained manufacturing but no one could identify the logistical cost of the operation as this was hidden within the procurement cost. Further to this, the complexity of all the channels made service level agreements difficult to maintain and manage, giving rise to safety stocks and non-value-add cost. The inbound supply chain was mapped from a time, cost and value-add perspective.

Horizontal channels of supply were identified and a neutral third-party logistics provider was given responsibility for implementation and delivery. This provided ownership, the ability to consolidate flows and a new focus on the factory as a customer of the logistics service and not just the product. Resource allocation in terms of inventory, transport, warehouse and IT capacity was designed into the solution on the basis of balancing service and cost, rather than using a just-in-case mentality driven by pure procurement and sometimes emotionally perceived needs.

Time Compression and the Future

At the time when the author was working on the Time Compression Program, no significant tool existed to assist with the production of time-based process maps. Excel spreadsheets help to a limited extent but are not automated or tailored sufficiently to use in a seminar environment. Typically seminars are the appropriate way to engage users and obtain buy-in to any diagnosis, change plan or potential solution.

Since the TCP disbanded, software tools have come a long way and the following wish list of support tool features is now a reality:

Discovery of process:

Simple process flows with automatic translation into a TBPM.

Cross-reference every element contained in above into a relational - database.

Every aspect of process, including time, cost and resource levels, embedded within one map.

Realization, improvement and deployment of process:

Ability to perform and enable what-if, impact analysis and reengineering.

Provision of logical links to objectives, customer value propositions, organizational structures, functions, regulatory structures, quality conformance regimes, supporting documents, software applications etc.

Software requirements definition, testing and implementation. - Continuous improvement of process:

Enable change via effective communication and user engagement. - Support ongoing operations and continuous improvement. - Governance of change:

Version control all of the above between users and various versions, - scenarios and variances of the process so that incremental improvements can be rolled out over time.

Notification provided to all stakeholders when changes affect - their role.

One software application that exists and provides most of the above and which is being further developed to support time compress re-engineering is Nimbus Control (FIG. 5). The potential that this tool offers for assisting business improvement in general is immense. It is therefore anticipated that time compression, alongside a range of complementary business initiatives driven by the use of tools such as Control, will become more widespread in the near future.

Conclusion

Time, as a measure, has been established as being strategically significant for contemporary business. The scale of time compression that is possible in most businesses is very significant because non-value-add time in most processes is at least 95 percent. The impact of commercial benefit is wide and includes increased market share, price, productivity and innovation together with reduced levels of commercial risk.

Time compression has been established as a mechanism for addressing most of the aspects of business strategy and overarches the key objectives associated with in-company logistics and managing the broader supply chain. Six principles aligned with the latter have been identified and linked to the idea of the time-based approach. To identify and achieve the time compression objectives, some tools such as time-based process mapping have been noted and coupled with a strategic re-engineering framework.

===========

==========

The approach supports a new source of competitiveness for time sensitive markets and, as a focusing criterion, it enables one company or supply chain to be compared with another in terms of the internal and external benefits of time. This can provide the impetus for change and an improvement plan. Even the end user or the internal supply chain customer not operating in a time-sensitive market would find it difficult to argue that a benefit could not be acquired from the application of time compression. The approach does, however, require a top-down commitment and for full impact a lead organization within a supply chain needs to drive the initiative. This can become a challenge where trust is an issue and there is the need for an unbiased hand to guide, arbitrate and have a stake in the process.

Looking towards the future, companies must blend leanness with agility in order to be able to respond to at least two possible key challenges. The first is ensure that supply chains are designed, operated and evolved to meet and drive end-user needs. The second is to manage the supply chain in a dynamic commercial environment that is making network management rather than supply chain management a challenging reality. The time compression approach's simplicity and transparency across company and functional boundaries provide a good platform for meeting these challenges.

top of page Home Similar Articles