This section explores the 'time compression' approach to business process improvement in the supply chain. The concept and strategic relevance of this approach were first published in the West in the early 1990s; however, it is an approach that still offers good potential and a fresh approach to achieving competitiveness through re-engineering. The rate of adoption of 'time compression' has been slow and part of the reason for this is that the approach requires the total commitment of the whole business, from the top of the organization downwards. Coupled with this is the fact that change within any organization has always been challenging, particularly when it involves making difficult decisions in one department or function to benefit another for the good of the whole company or even supply chain. Supply chain objectives and their relation to time compression implementation strategies will be touched on, coupled with explanations of achievable benefits and case study examples.

Over 200 years ago, Benjamin Franklin stated that 'Time is Money', and this was reiterated in 1990 by Stalk and Hout who claimed that 'time is the last exploitable resource'. Today 'time' is still largely ignored by many companies owing to enduring approaches that create inertia in organizational structures and associated business processes. Managers have always used time to manage their operations but control has usually been limited to a segment, or business function, within the supply chain. For example, in the past, 'time' has been used for 'work study' and human performance measurement, but this approach is based on the use of past observations in relation to operations usually associated with a long-established and outdated business processes. Moreover, this approach, and even some modern-day approaches, focus purely on the value-adding elements of business process that often account for only 5 percent (sometimes referred to as the business process velocity) of total process time. This emphasis on just the value-add time tends to be focused around making people work faster, often with a risk to quality, safety and ultimately livelihoods as competitiveness starts to become an issue. There is also another problematical dimension to these approaches in that the time based implications of individual actions recognized only one side of a 'trade-off' that may have holistic implications in a much broader supply chain context. Examples include companies that manage capacity and cost through applications and frameworks such as traditional accounting, functional budgeting, manufacturing resource planning (MRPII) and even enterprise resource planning (ERP). The resultant scope of thinking is usually constrained by not recognizing how time, stock, resource and service interrelate with each other along the supply chain. Using 'time' as a measure creates a deeper understanding of the total holistic business process, therefore providing scope for optimization and a pragmatic approach to change. The use of time in this context is directly linked with competitiveness, and this is what is meant by the 'time compression' approach.

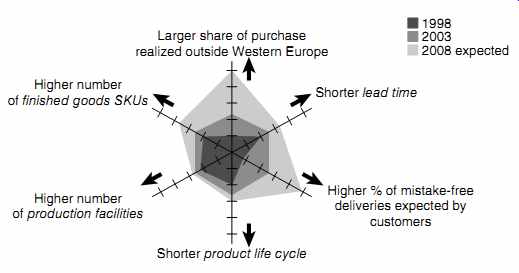

--------------

Shorter product life cycle

Larger share of purchase realized outside Western Europe

Higher number of finished goods SKUs Shorter lead time

Higher number of production facilities

Higher % of mistake-free deliveries expected by customers

1998 2008 expected 2003

FIG. 1 Complexity factors relative change (2003 = 100)

----------------

Time Compression and Competition

Wormack, Jones and Roos's landmark work within the automotive sector in 1990 pointed out that competition had become more aggressive and customers more demanding, so there was a constant need for a new source of competitiveness. In 1991 Riech went further and demonstrated the general applicability of this statement in a global context across many industrial sectors. Global competitive forces around the world are placing increasing pressures on markets and supply chains. Demand for increased service, product performance and variety across supply chains that ex tend across the globe create new requirements and challenges.

The time compression approach is one route to addressing these demands and improving the design, balance and flexibility of the supply chain. If this approach is combined with a focus on customers that operate in markets that are time-sensitive, then a further dimension is added.

Stalk and Hout (1990) make the comment that 'the world is moving to increased variety with better levels of service and faster levels of innovation. For suppliers that operate and service these sectors, time based competition is of significant advantage'.

A survey conducted by the European Logistics Association in 2004 identified factors that are increasing the complexity of supply chains; see FIG. 1. This highlights the current and continuing trend to source product outside of traditional supply markets, and this is coupled with the concerns and demand for mistake-free deliveries. Despite the presence of these two significant factors, the increase in stock-keeping units (SKUs) will continue, as will demand for shorter lead times.

These results have today manifested themselves, with cycle times being a key consideration for most companies in the West. It is interesting, however, to note that the more holistic approach offered by time compression remains an opportunity for many companies. This, for example, is borne out by the content of numerous industrial requests for quotation (RFQs) directed to third-party logistics providers over the past decade.

The majority of these tend to focus on cost reduction, with often little or no consideration for the attainment of holistic supply chain benefits.

The question is why some of the major corporations seem to ignore or do not directly engage with this approach. The answer may lie in the fact that the use of time compression to some extent relies on viewing the supply chain as a business process that can be designed and managed, i.e. the original concept of supply chain management (SCM). Some commentators such as Lamming (2002) consider that the idea of managing the supply chain as a holistic entity using approaches such as SCM is totally impractical. He considers SCM to be a flawed concept because it has been around since 1982 and industry is still having difficulty with implementing and mastering this area of potential competitiveness. This may well explain, or support, the reason why some of the more insular approaches to business improvement still dominate company key objectives. This debate will no doubt continue irrespective of whether SCM or, say, network management is the approach for the future. Opportunities, however, for time compression still exist and this will be explored further.

What is time compression? The key aspect for the use of 'time' is that it is not necessarily about being faster or the fastest. Quality is paramount to competitiveness and substituting, say, quality for speed is not the primary objective. A time compression approach focuses on how companies use time to deliver a sustainable fast response to customer needs, through business processes that are organized around a strategic time-based focus. The concept is about strengthening the holistic supply chain structure to achieve time based objectives, with tactical decisions being made at the correct level to enable the speed of response.

The term time compression was originally introduced by New in 1992, and in its most basic form relates to the reduction of the time consumed by business processes through the elimination of non-value-adding process time. Value-add processes are defined as entities that transform inputs into outputs that are of value to the customer and that they are willing to pay for (or negate their costs) and involve no correction or rework, i.e. right first time. Some processes may be identified as producing very little added value and this may highlight the need to totally re engineer them. This can take advantage of a number of possible strategies detailed below.

=====================

Table 1 SCM principles relating to time

Nature of the principle

Useful attributes of a time compression approach

[The principle of end-user focus

The principle of horizontal boundary definition

The principle of vertical boundary definition

The principle of inventory positioning

The principle of control over demand dynamics

The principle of cooperation and coordination]

[ Long-term supply chain profitability is dependent on the end (ultimate) user being satisfied. This acts as the focus for all supply chain design, development and process engineering.

Different end-user needs are more competitively satisfied by channels (horizontally defined routes or workflow) designed and engineered ideally across the supply chain from a logistics service perspective.

Boundaries of ownership and control (dividing the chain vertically) should be positioned to suit the needs of the end user according to best practice and make / buy theory.

The positioning, levels and characteristics of inventory are best determined in a total supply chain context to suit end-user needs in line with stock and postponement theory.

Understanding and levels of control over demand dynamics are best achieved by having a holistic supply chain perspective.

The principal basis is through information integration and the use of best practice relationship management.

The attainment of the above principles requires cooperation and coordination between supply chain participants. For this to work effectively each SC participant must have self defined and motivating objectives based on trust and some common business aspirations.

]

[

Time compression requires that the end user is identified as the principal anchor point. This provides the focus for all time-based parameter measurement across the supply chain.

Time defines the principal characteristics of the logistically distinct channels and service needs. The time compression approach provides a good diagnostic and basis for redesign.

The consumption of non-value time highlights where ownership and general boundary issues exist and require adjustment.

Time and cost provide a good deterministic framework with cycle time as a fundamental driver of stock positioning, levels and service. 'Value add stock' is a time-based diagnostic.

Time measures the problem and time compression tackles the root causes of demand dynamics.

Time provides a common and trustworthy metric across the supply chain that highlights the opportunities and issues.

]

========

One of the reasons why the approach is important relates to the levels of time compression that can be achieved across business processes.

Within, for example, a typical US or UK manufacturing company at least 95 percent of the process time is accounted as non-value-adding. This well established statistic was supported in the UK by the TCP ( University of Warwick's Time Compression Program) in 1995 and in the United States by Barker in 1994. Consultants in 2004 (SUCCESS, 2004) confirm that these sorts of value-add statistics still hold true, making the approach powerful as well as relevant in today's business environment.

If this statistic is viewed in the context of a typical supply chain, as little as 0.01 percent of time can add value. However, as New (1992) demonstrated, all of these percentages require qualification on two counts. First, a large proportion of the non-value-adding time is due to product queuing, so the value-adding percentage is a function of how much is being pushed through the supply chain at a particular point in time. Even if a particular supply chain is grossly inefficient, but had only one order during a particular period, the actual value-adding time would be high because of minimal queuing. A second consideration is that inventory should add value and it is, therefore, usually included in the overall value-adding percentage. Consequently a view has to be taken on how much of the inventory element of the pipeline - usually measured in days or hours of throughput cover - is actually adding value. The amount of value added by inventory is intrinsically linked to the process cycle times, as well as demand throughput levels and predictability.

The statistics do, however, show the enormity of the opportunities for companies and their associated supply chains - and they differ significantly from any perceived opportunity that might be available from, say, a cost-based approach.

Time compression can be achieved using any one or a combination of seven strategies identified by Carter, Melnyk and Handfield (1994) and these can be applied from company level through to a total supply chain.

These are summarized below:

simplification, removing process complexity that has accumulated over time;

integration, improving information flows and linkages to create enhanced operability and visibility;

standardization, using generic best practice processes, standardized components and modules and information protocols;

concurrent working, moving from sequential to parallel working by using, for example, teams and other forms of process integration;

variance control, monitoring processes and detecting problems at an early stage so that corrective action can be taken to avoid problems with quality and waste; automation, applied to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of entities and activities within the supply chain process;

resource planning, allocating resources in line with SCM best practice.

For example, plan by investigating bottleneck activities and consider use of multi-skilled workforces to provide resource flexibility.

These strategies should ideally be utilized in the sequence they appear above. However, depending on any particular supply chain or company situation, various stages and combinations may be more pragmatically deployed to account for changes that are already, or about to be put, in place. Through the use of these strategies, time compression can directly achieve increases in value-add time and help to contribute to objectives associated with fundamental principles of SCM and best practice. Putting segment of the supply chain in question should operate on a 'just in time' or a 'make to order' basis. This total supply chain perspective may remove or displace the stock point and hence the requirement for a WMS at this point. In addition, if process times are compressed in other parts of the supply chain, the economic structure of the supply system may change the appropriate locations for inventory stock points, and the short-term cost savings associated with the proposed warehouse system could be negated by a new inventory regime. If the new WMS is still established, its associated payback demands may impose an inappropriate constraint preventing future supply chain optimization. This will have ramifications in terms of cost as well as service levels, flexibility and agility.

The Time Compression Approach -- Cost Advantage

Cost reduction will generally occur as a direct result of the removal or compression of non-value-added time. This time compression can result in a number of cost savings associated with the removal of fixed and variable overheads (such as rent and management), direct costs (such as labor and materials) and working capital. Other cost savings will depend on the nature of the compression, perhaps minimizing risk in the decision process by making relevant information available earlier in the process. The reduction, or even removal, of a rework activity can result from process change such as compression of information queues. These improvements can also have ramifications downstream and upstream of the chain by reducing or removing expediting activities that are in place to cope with ongoing inadequacies.

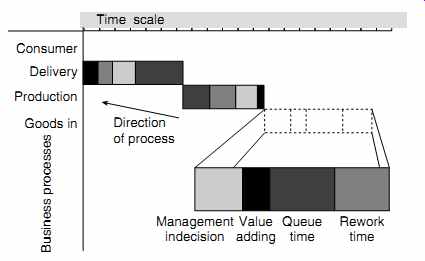

FIG. 2 Time-based process mapping - value-add analysis

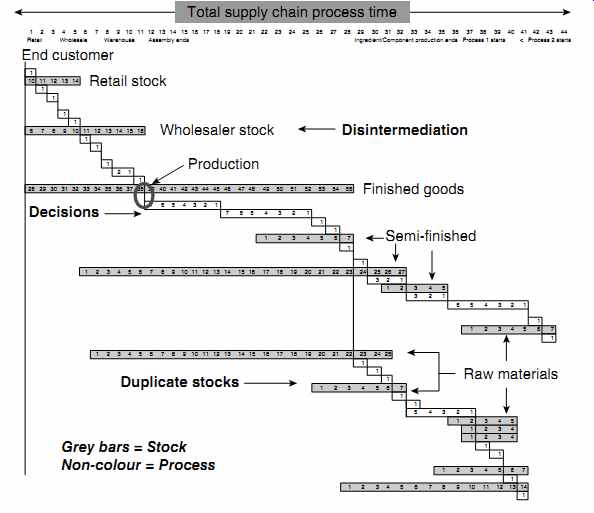

FIG. 3 Time-based process map of an entire supply chain. This UK example

shows the key processes that move material out of the ground and maps the

processes that evolve the material into something that fulfils customer

demand. Value time is not displayed in this view; however, value analysis

revealed that the aspects noted in bold are key issues. The longest process

time in this example was the decision-making process, which consumed 14

days and is therefore the largest element of the finished goods supply lead

time. In contrast, the overall production time of just a few minutes is

the shortest element

The cost implications of compressing time are extensive and complex but rarely absent. This is why the prescribed approach is to focus on time, which directly affects the service a supply chain can offer, without the complications of having to identify every cost 'trade-off'. The cost based focus has been encouraged in the past by the use of performance measures linking profit margins with cost. With the 'time compression' approach there may be a requirement to determine cost values associated with the processes to assist with evaluation and project prioritization.

Generally, the time-based implications of any proposal are easy to comprehend and quantify, because the length of time consumed by processes is typically a proportional representation of the costs (New, 1992).

The SUCCESS program, a joint university and industry-led initiative, developed a tool kit called the Supply Chain Time and Cost Mapping (SCTCM). This usefully combines time-based process mapping with process cost analysis. The former highlights opportunities using value-add analysis (see the example in FIG. 2), and the latter translates and attributes functional costs to processes. SCTCM has the benefit of being able to see how time, value-add and cost interrelate with each other along the supply chain. This can be useful for prioritizing projects, analysis and gaining buy-in to the time compression approach.

This, however, needs to be carefully weighed against the issue of collecting vast quantities of cost-based data at the risk of prolonging total project duration. It may also be a particular issue when the cooperation of process owners and operators is required for the project because it can then be perceived as a cost-cutting exercise. As a consequence, using these individuals to help with data collection, analysis and solution design may become more challenging. SCTCM is, however, a positive recent development, which keeps time compression on the re-engineering agenda through the use of a rigorous project tool set and application process. The link to commerce's acute focus on cost provides the approach with the added credibility and robustness that is often required.

Time-based process mapping - value-add analysis

The time compression approach - quality advantage

The achievement of time compression requires a quality-based approach.

This can be viewed from two perspectives of quality. First, time compression demands that product quality is to a specification that matches customer needs and more specifically end-user needs. Anything less will obviously have strategic market implications, such as a loss of customers and goodwill. This will consume unnecessary time in the sales, marketing and manufacturing process, which will have to rectify or replace the product or customers. An investigation of these time-wasting activities can, therefore, highlight possible root causes of problems that may be founded in quality issues. Time, therefore, provides the focus for quality improvement.

The above complements the second dimension of quality where it is not just important for the customer but also for the company. This is the total quality management (TQM) approach (Oakland and Beardmore, 1995), which also focuses on waste elimination. One key issue with TQM program is that they have been known to lose impetus because of a lack of focus. Mallinger (1993) and Glover (1993) identify the need for a holistic approach to provide a focus for TQM to operate effectively. A time compression approach provides this because it uses a simple measure that is visible to the total supply chain and not just a small isolated segment. It can thus link and integrate all of the elements of a TQM approach using the key metric of 'time'. An example of this might be a focus on the time taken to make critical decisions that in effect constrain an order or product batch being processed. Typically sales and operations meetings tasked with matching demand and production may represent this process constraint, as illustrated in the TBPM shown in FIG. 3. By implication, the lapse times of these meetings sit on the critical path of any supply chain process. The majority of this time is non-value-add and therefore provides a key focus for addressing the total quality of all activities that interplay with the process. Examples will include the major quality-related aspects, from systems to produce accurate and timely information through to the more routine but easily under estimated aspects such as people attending meetings on time, effective communications and proper prioritization of tasks and activities. The non-value activity, particularly the low-profile issues, may not be generally recorded from a cost perspective but the delay on the critical path can be measured in terms of inventory cover and customer lead time and is therefore high visible.

The Time Compression Approach -- Technology Advantage

Technology should not be applied purely for reasons associated with what is on offer or mimicking the competition. Its application must take account of the individual circumstances of the business and its customer needs, and then ensure a competitive differentiation. A focus on the time based impact of the application of technology will help steer a company to this goal. Examples of technologies that can achieve time compression are numerous and some of the more notable developments (Barker and Helms, 1992) include: computer numerically controlled (CNC) machines, robotics, computers in manufacturing (CIM) and logistics-related examples such as the WMS application mentioned earlier. All of these reduce time for individual activities, but the time-based impact must be considered holistically in order to check that the technology is appropriate for the supply chain. A key perspective is that many automated systems cannot cope with high levels of demand variation, largely because the technology is designed against very exacting functional specifications. A time compression approach provides the focus for the application of technology when the seven strategies identified by Carter et al are addressed in a carefully considered sequence. This usually considers the low- or non-technology strategy solution before moving to state-of-the-art automated solutions, such as computerized material handling and control or the various forms of ERP. This approach will ensure that the application of technology is strategically significant as well as delivering tactical productivity gains. NEXT>>

top of page Home Similar Articles