As far as the modern discipline of microeconomics is concerned, incentives play a central role in supplier management. Indeed, arguably they play the central role. It is incentives (in the form of gains from trade) that bring buyers and suppliers together in the first place, and it is incentives that govern the nature of that relationship thereafter. Incentives determine the decision to outsource, the choice of trading partner and the depth of trading relationship, as well as the terms of trade. Without incentives there would be no suppliers and there would be no supply management.

This is hardly a controversial assertion; today's microeconomics rests upon it. However, when surveying the existing literature on the subject it becomes clear that literature is not so much wrong as incomplete. This is because the preponderance of what has been written treats the firm as though it were a black box. Profit optimization is assumed to be axiomatic, with both parties striving to maximize the returns to their respective shareholders. Because this is the case, activities within the firm are held to be of second-order importance.

However, such a belief sits uncomfortably with the everyday experience of supply managers. A supply manager is acutely aware that his or her choices are not made in a vacuum. They are highly political in that they have an impact, not only on the supplier, but on other actors within the firm. Some choices leave supply managers pushing at an open door, in that they find a receptive audience among internal stakeholders. Other choices are more controversial, though. They unsettle a status quo to which a stakeholder has become accustomed, or finds profitable. Where such is the case, supply managers can count on finding themselves opposed. Where such a stakeholder is powerful, he or she is able to exercise a veto over what is being proposed.

This section seeks to describe the role played by incentives in supply management. Using mainstream analysis, it covers the traditional literature on inter-organization relationships. However, it also examines the politics of supply management, and particularly the potential influence of powerful internal actors on the supply management process.

Collaboration vs. Competition and the Role of Incentives in the Exchange Process

All exchange involves elements of both cooperation and competition.

Assuming that the parties concerned have voluntarily agreed to the deal, the very act of signing a contract is a cooperative activity. The vendor (or seller) is getting something that it wants - cash - while the buyer is getting something it wants - the products and services supplied by the vendor. However, the cooperative aspects of an exchange can (and frequently do) go beyond this. Buyers and sellers can actively work together to streamline the contracting process and / or adapt / develop the vendor's products and services so that they more closely match the requirements of the buyer. The creation of such value-adding relation ships has today become a staple of supply chain management.

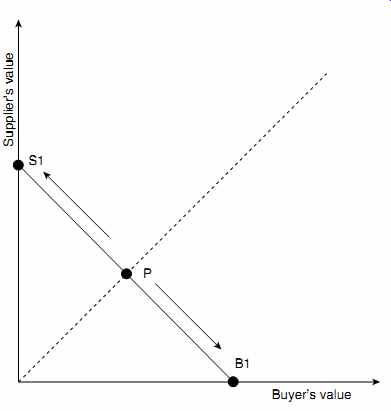

FIG. 1 Conflict and the exchange process

Buyers and sellers are also in competition, however. While both sides gain from a trade (else why trade in the first instance), it is not necessary for both sides to gain equally for a trade to take place. For the buyer, the aim is to get value for money from a deal. If it is a rational agent, this means maximum value for money. Every time it is able to negotiate the contract price down a notch, the value for money that is obtained in creases. Of course, for the vendor, passing value to its customers means smaller profits. Economists refer to the contested ground that exists between the two parties to a trade as the surplus value. Surplus value is the difference between the value that the customer places on the vendor's products (i.e. the customer's utility function) and the supplier's costs of production. That portion of the contested ground that passes to the customer is said to be the consumer surplus, while that which is retained by the vendor is the producer surplus. This competitive element is represented in FIG. 1, where the potential returns (or surplus value) are assumed to be fixed (B1-S1). However, the proportion of the returns that falls to the buyer increases the closer the contract price moves towards the x-axis. Conversely, the returns to the buyer increase the closer the contract price moves towards the y-axis. Where the contract price falls equidistant between B1 and S1, the gains from trade are shared equally (point P). Typically this is referred to in the literature as a win-win.

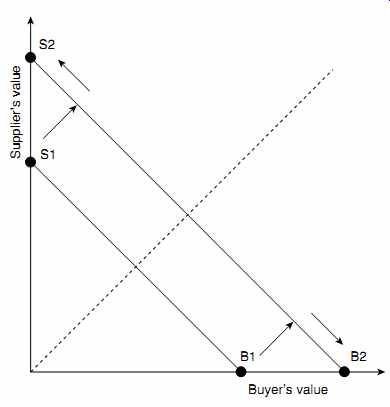

FIG. 2 depicts the value-adding nature of some relationships. Here, the surplus value is not fixed, but as a result of cooperation it increases from B1-S1 to B2 -S2.

FIG. 2 Cooperation and the exchange process

However, even when buyers and sellers increase the cooperative element of an exchange by actively working together to add value to the relationship, the competitive element to it remains, i.e. cooperative relationships can be adversarial or non-adversarial. This is because the fruits of the cooperation (in the form of either lower production costs for the vendor or a higher valuation of the vendor's products on the part of the customer) have to be divided up. If, for example, the effect of collaboration is to reduce the supplier's costs by $150 a unit, there would be an issue about whether the vendor should pass all of the savings on to the customer or whether it should retain some of them in the form of higher profits. Alternatively, if the supplier invests $150 in developing its products and as a result increases the value to the customer by $270, should the vendor raise its prices by $150 to cover just the cost of the investment, or by the full $270?

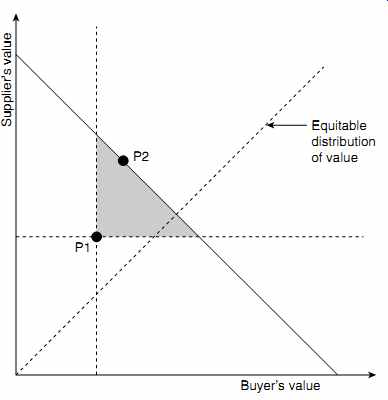

FIG. 3 Cooperation and conflict in the exchange process: supplier-dominated

supplier development

FIG. 3 illustrates this dual dimension to the exchange process. In FIG. 3 the two parties start the relationship at point P1, which sits above the point where the dotted line (which runs 45° from the origin) bisects the line of surplus value. Ex ante, therefore, while the association operated to the advantage of both parties, it benefited the vendor more than it did the buyer. Ex post, after the contract price has shifted to point P2, this is still true. The diagram clearly shows that the gains from collaboration have been mutual. This is because point P2 sits both above and to the right of point P1 (indicated by the shaded triangle). And whenever a new contract price moves to the right of the original settlement it indicates a gain to the buyer; whenever it moves above the original settlement point, the vendor has gained also. This is what economists refer to as a Pareto improvement. However, while both parties have gained from the collaborative process, they have not gained equally. The vendor is still, relatively speaking, the better off (because the contract price sits above the dotted diagonal line, which indicates an equitable settlement).

Whether a relationship is predominantly adversarial or has a significant cooperative component, what determines who wins out in this competitive process are the incentive structures that underpin the exchange relationship. Take, for example, the vendor that finds itself in a highly competitive market where its many customers are free to pick and choose where they buy their goods and services. Such a context forces the vendor into a Dutch auction in which it is forced constantly to drop its prices to buy its customer's business. In such a situation, the surplus value is bound to pass to the consumer (i.e. towards the x-axis). Compare that to a situation in which a particular customer has invested heavily in the vendor's technologies, even building the value proposition that it offers its own customers around the technologies of a particular supplier. This happened in the case of the PC market where PC manufacturers fell over themselves to advertise the fact that their machines had 'Intel inside'. In the end, it became impossible for PC manufacturers to compete unless they were able to make this boast. Unfortunately, this had the effect of handing enormous leverage over to Intel and as a result the surplus value passed from the consumer to the producer (i.e. towards the y-axis).

Consequently, much of supply management is reduced to game between poachers and gamekeepers in which the vendor assumes the role of the poacher (trying to 'steal' its customers' scarce financial resources), while the procurement manager assumes the role of the gamekeeper, in trying to stop them. What follows is a cat and mouse game in which, through a combination of guile and the development of distinctive capabilities, the vendor attempts to close markets, while the buyer's procurement manager responds in kind with a range of counter-strategies, designed to stop its vendors by keeping its supply markets contested. To the victor go the spoils. Power (formally defined as the ability of one party to adversely affect the interests of another) and the pursuit of power are at the heart of the exchange process.

To some, it might appear that the competitive elements of an exchange have been overstated. While it is true that some people in life are maximizers (i.e. they are always looking for the highest possible return from a deal), critics would argue that most people are in fact happy just to 'satisfice' (i.e. obtain a settlement that provides them with a deal that they can live with). If two people cooperate on a venture, then generally speaking those people are happy to split the proceeds. This may or may not be true; it is hard to say. What is true, however, is that such an approach is suboptimal and imprudent. That satisficing is suboptimal should be self evident. The fact that it is also imprudent needs further elaboration.

The issue of prudence arises in a number of contexts. First, it puts the profitability and even the survival of a firm at risk. The reason that firms come into business in the first instance is to make a return for shareholders.

While it is true, as a number of resource-based writers have observed, that markets are often heterogeneous (i.e. they are capable of supporting laggards as well as world beaters), it is not true that markets are infinitely forgiving of the weak. Firms that fall too far behind the competitive frontier are on borrowed time. Firms that forget about the competitive elements of an exchange, however, risk seeing their costs rise and falling behind the competitive frontier.

The second problem with cooperation and trust is that it demonstrates an unwarranted confidence in the capacity / willingness of others to reciprocate. Many firms that acquire leverage are happy to use it. Even those who do not possess a structural advantage may attempt to use guile instead, where they think it will pay off for them. Furthermore, denials that this is not true cannot be taken at face value. The thing about people is that very few of them are honest all of the time. One only has to reflect on one's own experience to see that this is true.

According to business economists, economic agents are not simply self-interested but they pursue this self-interest with guile - not all of the time, but sufficiently often that opportunism is a fact of commercial life. What permits the existence of opportunism is two things: a lack of honesty (obviously); and a lack of transparency between buyers and sellers. Economists distinguish between public and private information. Information is regarded as public if it involves something that is widely known. Information is regarded as private when access to it is restricted. When 'restriction' means that one side in an exchange knows something that the other side does not, then an information asymmetry is said to exist. It is information asymmetry that permits dishonesty to pay.

Business opportunism exists in a number of forms but for buyers the three guises in which it is most common are adverse selection, moral hazard and hold-up. Adverse selection is ex ante opportunism or mis representation that arises prior to the signing of a contract. Shorthand definitions of the concept might revolve around buying a 'lemon' or being sold a 'turkey'. The scope for adverse selection varies but is more common under some circumstances than others. Commentators often distinguish between search, experience and credence goods. Search goods are products that allow buyers to make systematic comparisons prior to a purchase. They are normally tangible products like chairs, pens or iron ingots. Experience goods, by contrast, are products that can only be evaluated subsequent to purchase. Typically, they include services like cinemas or restaurants. However, the category can also include tangible products like cars or records. The final category of good is the credence good. Credence goods defy easy evaluation, even after consumption.

They include intangible services such as advertising, consultancy or medical services. What makes evaluation so hard usually comes down to a difficulty with attributing blame or success. For example, a piece of professional advice might have been responsible for a commercial disaster.

However, the blame might lie with some other concomitant factor. The point is that where pre-contractual evaluation of a product is difficult - either because evaluation is inherently difficult or because the buyer lacks the resources or expertise to undertake it - the buyer is open to the risk of adverse selection. Experience goods and credence goods, by definition, are difficult to evaluate prior to purchase.

If adverse selection involves being suckered before a contract is signed, moral hazard and hold-up involve being suckered once a party has signed on the dotted line. Moral hazard is concerned with shortfalls in effort. For example, prior to an agreement, a consultancy company might promise to dedicate its best staff to the task of servicing the client and set its costs accordingly. Unbeknown to the client, however, once the contract has been secured, the work is passed down to junior colleagues whose time is charged out at inflated rates. Alternatively, moral hazard may involve charging a client for materials that were never used or which were used but which came from another job and which had been paid for by another client.

Hold-up occurs as a result of an extended association with a supplier, where the terms of the association cannot be fully specified in advance and where the association requires one of the parties to incur significant sunk and / or switching costs. As, with time, the full requirements of the relationship are revealed, this combination of factors allows the non dependent party to renegotiate the terms of the deal in ways that are most favorable to it. According to some observers, it is the incompleteness of the original agreement that gives rise to the need for subsequent renegotiation. However, for Williamson it is the existence of high sunk and switching costs, in combination with the initial uncertainty, which is the source of the problem. It is this that can support blatantly opportunistic behavior in which the non-dependent party is even able to renege on promises that are covered by a legal agreement. The calculation here is that any benefit that can be obtained through legal redress will be insufficient to compensate for the damage to, or loss of, the relationship.

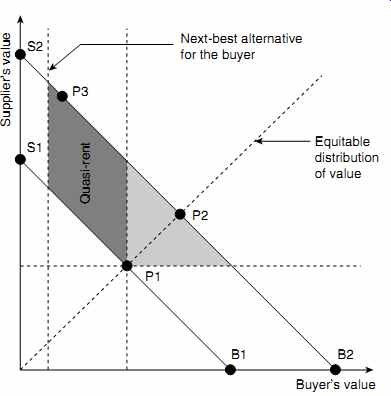

The dominant party is in a position to leverage the weaker party up until the point where it is more profitable for the weaker party to exit from the relationship than to continue to be extorted. Economists refer to the return enjoyed by the dominant party as a quasi-rent.

This is illustrated in FIG. 4, where both parties start with equal power and an initial settlement point P1. As a result of the dedicated in vestments made in support of the relationship, the surplus value increases from B1-S1 to B2 -S2. Based on the initial agreement, the buyer has an expectation that the final contract price will locate somewhere around point P2, and that the distribution of benefits in the relationship will remain equitable. In effect the relationship will deliver a win-win. However, in this case it is the buyer, rather than the supplier, who has made all of the dedicated investments. Based on the supplier's calculation of the buyer's sunk and switching costs, this allows the supplier to push the actual contract price to P3. This leaves the buyer worse off than it had been at the start of the relationship. However, it is still more efficient for the buyer to agree to the contract price than it is for it to write off the sunk and switching costs. Only if the supplier attempts to push the buyer beyond the threshold that marks the buyer's next-best option does it make sense for the buyer to exit from the relationship.

Regardless of whether Williamson is right and hold-up is the product of strategic behavior, or Klein is right and it is the product of the need to recalibrate the relationship as future contingencies become known, the relationship still needs to be renegotiated. This renegotiation, though it can deliver gains for both sides, is still a competitive process.

FIG. 4 Sunk and switching costs, and the problem of hold-up

Incentivization and the Question of Make vs Buy

Nowhere are the issues of competition between buyers and sellers more acute than with respect to outsourcing. This is evidenced by the fact that so many outsourced contracts go wrong. One survey found that in only 5 percent of cases did outsourcing prove to be an unqualified success. More often than not, respondents indicated that it was something of a curate's egg (that is, good in parts). Thirty-nine percent of respondents in the survey said that their outsourced contracts were simultaneously moderately successful and moderately unsuccessful. Of course, this may have something to do with the way in which the contracts were managed. (The issue of contractual mismanagement will be discussed in the next section.) Such is the scale of disappointment, however, that it suggests that something deeper than simply poor contracting is at work.

On the face of it, the decision to outsource should not be particularly problematic. It should involve a simple cost comparison between the expenses associated with undertaking the activity in-house as opposed to the expenses associated with contracting it out. For example, the size of the firm's requirement might be insufficient to cover the fixed costs associated with production in an efficient fashion. Under these conditions, sourcing externally, from a firm that can amortize its fixed costs more efficiently, might make eminent sense. Alternatively, a particular activity might be suffering from a lack of effective managerial oversight. Managerial time within the firm is a scarce resource and most of it tends to be devoted to the firm's key activities. Residual activities tend to get overlooked and production suffers as a result. It is this thinking that in effect underpins much of the core competence writing. If your firm can't do something well, find another firm that can.

Outsourcing tends to go wrong, however, because it exposes the firm to either a strategic or a contractual risk. Strategic risk arises if the firm outsources its competitive differentiator. Within strategy, there are three types of differentiation: cost leadership, product differentiation and niche production. In each case the firm is attempting to achieve the same thing through differentiation, i.e. break the relationship between cost, price and profit in order that it might earn an economic rent or sustained producer surplus. In a competitive marketplace, the consumer's ability to pick and choose between alternative vendors drives the firm's prices down towards the marginal cost of production. This is the last thing a firm wants.

In the case of cost leadership, the firm is attempting to earn a rent by developing a uniquely efficient production process that is difficult for its competitors to imitate through the creation of ex post barriers to entry. So long as the firm is able to stave off competitive imitation it can afford to drop its prices below those of its competitors and still make a higher return. In the case of product differentiation, by contrast, the firm is attempting to develop a superior utility proposition for the customer. The idea here is that when people comparison-shop and realize that the firm's products are better than those of its competitors, they will be prepared to pay a premium for the product that offers the higher utility. Again, its ability to sustain its producer surplus and turn it into a rent is contingent upon its capacity to hinder or retard competitive imitation. Finally, niche production also seeks to target customer's utility. This it achieves, however, not by creating relatively superior products but by servicing segments of a marketplace that nobody else is particularly interested in.

Because being able to differentiate competitively is so valuable to the firm (and indeed it is what strategy is all about), firms must be able to protect those resources and capabilities that generate the differentiation in the first place. However, if the firm outsources such a resource or capability then the odds are that it will end up paying to its supplier the rent that it should be earning for itself.

Outsourcing can also expose the firm to significant contractual risk (moral hazard and hold-up). Again, this involves the surplus value passing to the vendor, rather than being retained by the consumer. Sustaining the performance of a vendor depends upon a firm's ability to monitor or motivate it. Monitoring becomes more difficult after a competence has been outsourced because either the staff that used to manage the activity move onto the supplier's payroll, or else they are lost from the equation altogether. Once the organization lacks the resource, or at least resource that is sufficiently qualified to exercise proper oversight, the supplier starts to renege on its commitments.

Avoiding the risks of hold-up in an outsourced relationship involves maintaining motivational incentive. Such motivation might take the form of a carrot (bonuses for good performance) or a stick (the cancellation of the contract if the performance is poor). But in order for the incentive structure to work, the threat of sanctions as a last resort must be credible.

This means being able to monitor the supplier to see if it is complying with the terms of the deal; and having the ability to punish the supplier (by invoking penalties or by threatening exit), if it is not. Imagine a myopic and doddery old teacher trying to keep discipline in a playground if his head teacher has told him that even if he catches one of the children misbehaving, he is not allowed to threaten him or her with punishment.

Under such circumstances the children in his charge would run wild. So it is with suppliers.

The tasks that the firm has to perform, therefore, concern being able to spot those transactions for which there is significant scope for opportunism and being able to craft safeguards against the risk. Where contractual safeguards cannot properly be introduced, then the firm would probably be better to retain the competence within the organization, rather than to outsource it.

Hold-up is always a problem with outsourced contracts because effective monitoring is always an issue. However, sometimes the risks are particularly acute. Contracting that takes place in a highly volatile or uncertain environment is difficult because it raises the issue of renegotiation. Buyers attempt to draft contracts in as complete a fashion as possible, but when an environment is particularly volatile, specifying all the terms of an agreement in advance is likely to prove next to impossible.

This in itself need not present a difficulty unless the firm becomes locked into its outsourced provider. If this happens, the supplier may choose to renegotiate on terms that benefit it, rather than its customer.

As was indicated in the preceding section, contractual lock-in occurs if the contract requires the buyer to make some form of highly specialized investment in the relationship. The investment might take the form of time. An organization that has spent months negotiating and implementing an outsourced relationship might be reluctant to write off all of this hard work -- especially if re-sourcing means repeating the effort with no greater chance of success next time around. Alternatively, firms might have made substantial and non-fungible investments in specialized training or equipment (otherwise known as asset-specific investments). Less creditably, though, firms are often reluctant to call time on a poorly performing supplier if the managers who negotiated the contract have a significant reputational investment in the deal. Calling a halt to the affair means admitting that they got it wrong, and nobody likes doing that. Whatever the form of the lock-in, the effect is the same: the firm loses its capacity to impose costs on the vendor and thus its ability to impose discipline.

Of course, just because an outsourced contract presents the firm with a risk, it does not follow that the risk cannot be managed and that outsourcing should not take place. One strategy often pursued by firms involves unbundling a contract. This means separating out those elements that pose a risk from those that do not. The highly risky elements are retained in-house and only the less risky elements are outsourced. The supplier may even be asked to post a bond or share the costs of the dedicated investments, as a sign of its good faith (i.e. to show that its word of honor and commitment to the relationship are credible). NEXT>>

top of page Home Similar Articles