"Wood," wrote William Penn three centuries ago, "is a substance with a soul." Anybody who has ever worked with wood, who has come to appreciate the distinct personalities of oak and walnut, of pine and chestnut and cedar, would almost certainly have to agree. For warmth of color and texture, for unique patterning, for resilience and strength coupled with responsiveness to tools, there never has been another building material to rival it.

These qualities have been exploited over the centuries in many ways, as can be seen in the old and new examples of the woodworker's art on the following pages. Structural elements are deliberately left exposed to become part of the interior design of a room. Elsewhere wood is used purely for esthetic effect, as decoration. In still other homes, function and esthetics are combined in beautifully worked paneling, doors and railings.

Fortunately, throughout most of history, wood of all sorts has been in abundant supply. Prime woods, the likes of which are seldom seen in lumberyards today, once were used almost as casually as No. 2 Common is today. Such profligacy is no longer possible or desirable as select woods have become luxuries. But where wood can be celebrated--in paneling, in trim, in doors and in exposed structural members-craftsmen continue to delight in its timeless virtues, selecting the species to use for its particular combination of qualities.

Oak is prized for strength and durability, pine and fir for workability. A rustic interior wants exposed wood with a rough, strong grain, such as chestnut; mahogany and walnut have the sort of subtle gram that harmonize with a highly polished room. And where pronounced wood patterning or color is to play a major role in the effect you are after, it will certainly pay to hand-select lumber, board by board.

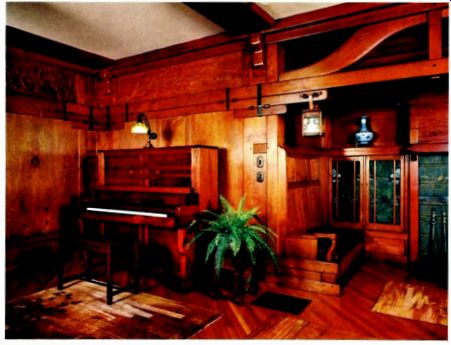

Some craftsmen want such subtle effects that they draft their final design only after they have the wood in hand and have studied it thoroughly. Charles and Henry Greene, the brother architects whose 1909 interior is shown on, designed the carved friezes with motifs of stylized branches in order to emphasize the grain of the individual pieces of mahogany.

Other woodworkers may find the simplest, plainest treatment of wood--with out carving, staining or any other civilizing refinements--the most congenial. It all depends upon the nature of the room and the instincts of the craftsman.

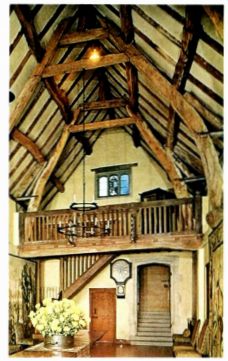

--------- A wealth of woodwork. A two-story entrance well provides a stunning glimpse of exposed, warm-toned wood in paneling, cornices, moldings. railings and rafters. In this yet-to-be-finished Connecticut residence, the builder-designers have incorporated touches of Victorian whimsy and grace, using old pine balusters, for example. and new door and window trim that has been hand-carved in the old manner. The round window, designed to be fitted with stained glass, is framed, barrel-style, in 6-inch strips of red cedar-one piece at center right is yet to be nailed. Cedar also frames the balcony enclosure and the diagonally paneled ceiling and walls.

Posts, Beams and Rafters Too Beautiful to Hide

Framing members, particularly it hand hewn of gracefully aged wood, add architectural muscle and sinew to an interior just by being visible. In colonial times, such an honest expression of the builder's art was often a matter of necessity, since plaster and paint were hard to gel.

As the colonies grew more prosperous, the chestnut, oak and pine that formed the rugged frames of houses were covered up. To the modern eye, however, such elements are freshly perceived as worthy of display for their surface texture and for the stark logic of their forms. The restoration of an old house is often an opportunity to reveal long-buried timbers. In constructing new houses, the de signer may choose to recycle timbers from torn-down buildings, or use new wood of suitable character.

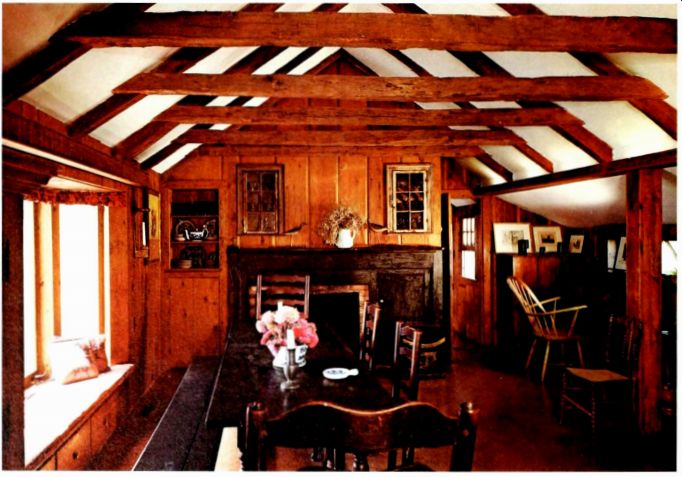

----- Apotheosis of a cow barn. The Great Hall of Packwood House,

Warwickshire,. England, began life in the 17th Century as a farm building,

but its handsome oak "crucks." or curved roof rafters, inspired

the owners to convert the space into a residence in the 1920s.

----------Salvage operation. Fine old timbers were among the many elements

that justified the reconstruction and remodeling of this old Long Island

farmhouse White-painted plaster between the heavy rafters, illuminated

by the light from a large bay window, dramatizes the woodwork.

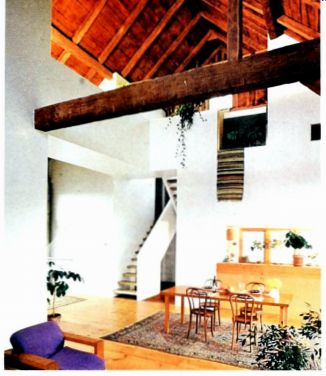

Rustic ceiling. In a Vermont hay barn-turned modern house, hundred-year-old oak rafters and board roof sheathing are preserved intact as the ceiling, a counterpoint for sleekly elegant plaster walls The rich toast color of the antique wood was brought up with sandblasting A layer of insulation plus an outer roof were added over the old for weather-tightness.

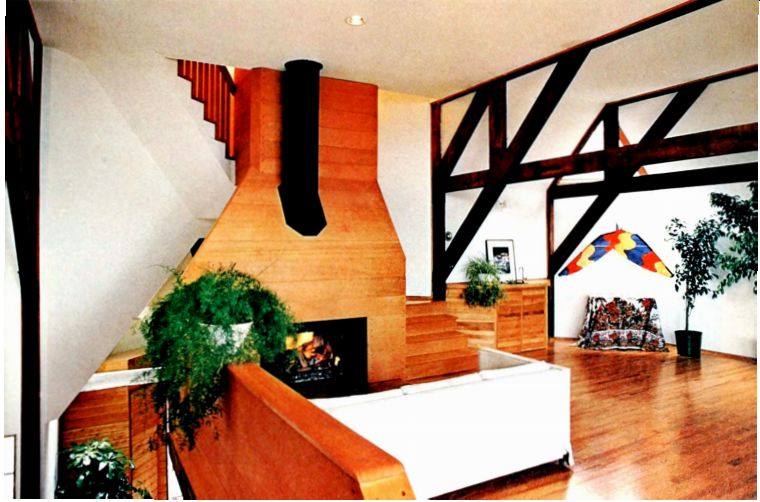

Modern geometry. Constructed with all new materials, this Connecticut country house borrows from the past in using rough-sawn beams and leaving some of them visible in this second-story living room. Their warmly weathered color was intensified during construction by 8 to 10 weeks' exposure to the elements.

--

Purely, Purposively Decorative

Ornamental woodwork often is passed over as unaffordable nowadays, but it once played a major part in interior finishing. Every era had its own finials, moldings and fretwork, and a craftsman had to execute them in the right combi nations and proportions. Such work still has a place, as part of an authentic reproduction or for its own eye-pleasing sake.

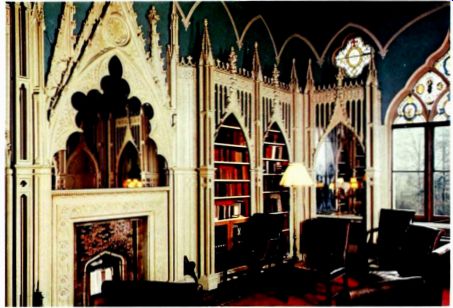

Gothic fantasies. Book niches, framed with filigreed wooden arches, are

among the experiments in Gothic Revival style at Horace Walpole's 18th

Century English villa. Strawberry Hill A medieval church screen inspired

the arches.

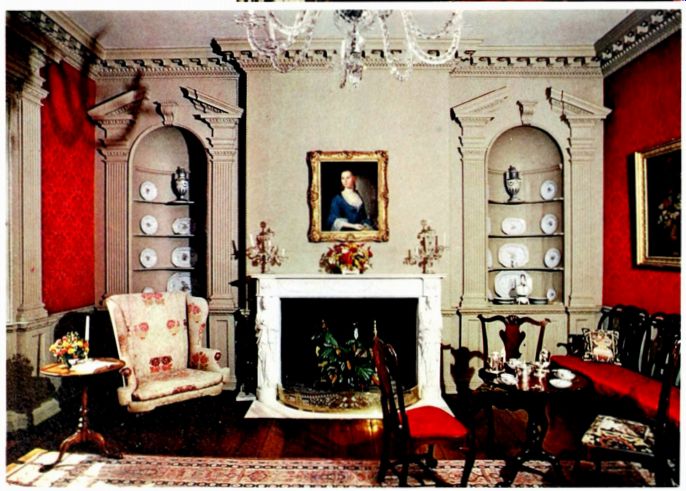

Classical craftsmanship. Designs of Roman antiquity, adapted in Renaissance

Italy and re adapted in colonial America, provide the pat terns for this

extravagantly detailed parlor in 18th Century Gunston Hall, Virginia

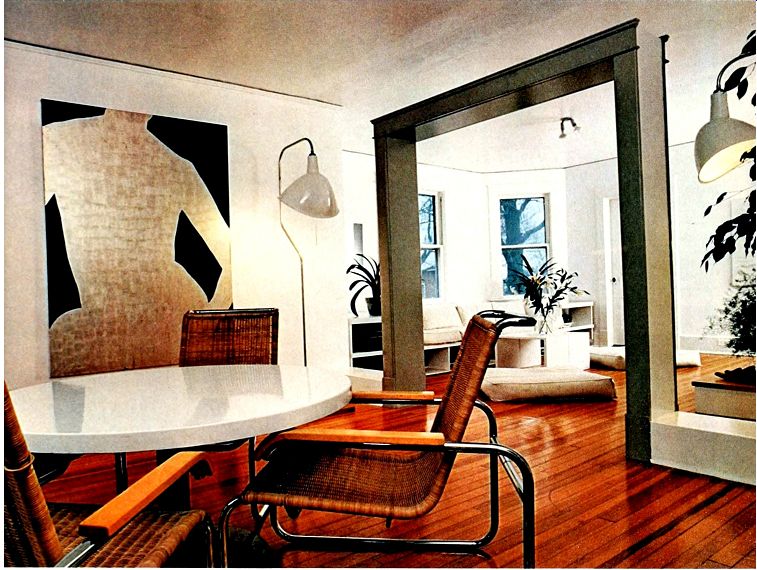

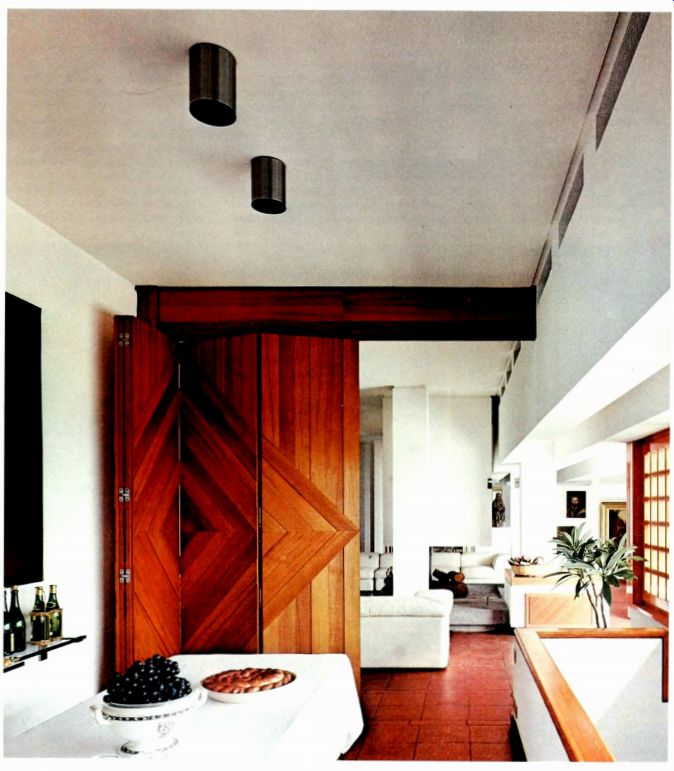

---- Triumphal arch. What was once the molded pine frame of a pair of

massive sliding doors has been preserved as freestanding sculpture in this

remodeling of a late-Victorian house on Long Island The open doorway maintains

the sense of two distinct living spaces provided by the solid walls of

the original floor plan, but without the drawbacks of restricted light

and movement.

Form and Function Joined

When decorative woodworking is linked with functional elements, the results can be even greater than the sum of the parts. Customarily, such unions have been consummated in decorative railings, in carved posts and beams, in elaborate doors and in wall and ceiling paneling. Though all of these continue to be used, paneling is perhaps the most frequently revived feature. It offers the broadest canvas for displaying the subtleties of wood grain, color and texture, whether it simply covers wall and ceiling surfaces, as in the examples below, or also becomes part of built-in furniture, as at right.

A delight in wood. Teak planks, gently rounded at the edges, oiled, and pegged with end-gram teak, reflect a silky, sensuous glow in the living room of a 1909 Greene Brothers house, which has beams, walls and furniture of wood.

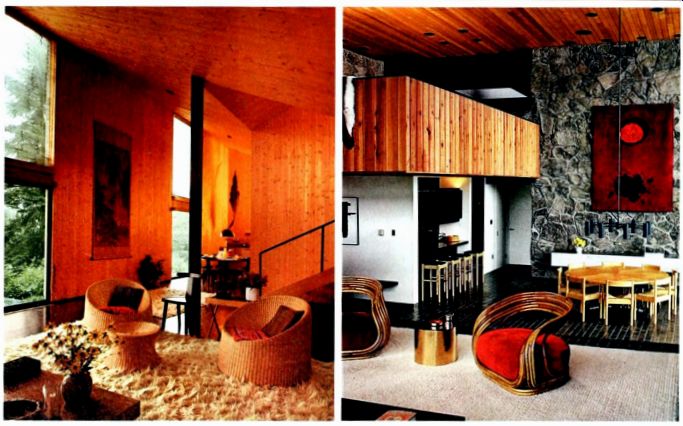

A rustic retreat. Taking its form and finishing inspiration from chalet construction, this Adirondack vacation house has interior walls and pitched ceiling sheathed in unfinished spruce Darker floors are fir; stairs and trim are cherry

Wood for warmth. Waxed cedar wraps the interior of a Colorado ski house in lively reds and browns to accent the gray of slate and stone Vertical planks, which catch the sun, are rough hewn, those overhead are polished smooth

---- Motifs in marquetry. A four-paneled folding door, put together in intricate patterns of teak diamonds within diamonds, screens the dining room from the two-story living room of a modern villa in Sicily. On the reverse side of the door, the same pattern fits into a towering wall of teak planking, most of it set vertically but interrupted with two smaller diamond insets. The window has small glass panes in deep mullions to help screen out the high sun of the Sicilian summer.

Flights of Fancy

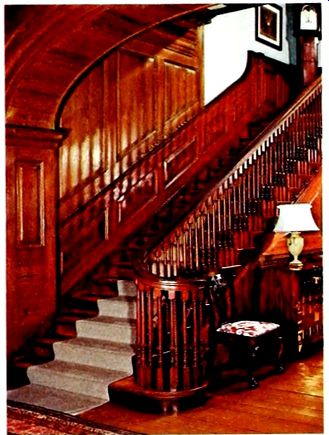

The staircase, with its enormous potential for architectural drama, naturally invites the designer's imagination; few parts of a house provide such opportunities for converting a utilitarian structure into a major element of design.

When stairs are constructed of wood, which lends itself so beautifully to ornamentation, they permit the virtuoso exercise of talent in carving, bending, turning and inlay to embellish the various parts from treads and risers to stringers, balusters, railings, newel posts, landings and paneling-that go to make up the functioning whole.

Renaissance and Baroque staircases had straight, muscular runs and closed stringers. From the mid-18th Century on, however, open stringers, their surfaces richly ornamented, were fitted with delicate balusters and graceful rails.

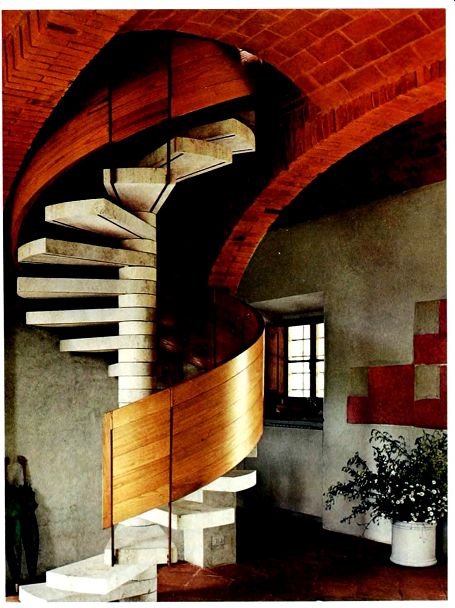

Curved stairs were also tried--some "flying" with a daring lack of visible sup port-but not until the advent of iron posts have freestanding wooden "snails," like that below, been possible.

--- Diagonal thrust. A massive wooden archway frames the grand stair of Carter's Grove in Virginia A superb example of the Colonial Georgian style, it has fine detailing that includes walnut nosings on the edges of the pine treads, nail-hiding plugs hand-carved in the shape of fleurs-de-lis, elaborately turned balusters, spiraled newels and beveled yellow-pine paneling.

---- A

helix for a balustrade. Complementing the vaulted ceiling of this

restored 1609 hunting lodge in Tuscany is a modern spiral stair with steps

of travertine marble cantilevered from a central iron post and wrapped

by a balustrade of chestnut-veneered pine The pine core was curved by steaming

Thin chestnut strips 9 feet long were then bent and glued to the pine in alternating bands 4 inches and 8 inches wide.

A Library for Carpenters

Unlike some other crafts of home repair and improvement, woodworking has inspired a literature remarkable for its depth and variety One of the earliest works in the English language on the subject, Mechanick Exercise, was published in 1677, and some books put out a century or more ago, such as Thomas Tredgold's 1840 Elementary Principles of Carpentry (below), are readable today.

New books for amateurs and professionals continue to be issued in a flood: the Library of Congress indexes 110 under " Woodworking--Amateurs' Manuals, " one of many classifications related to woodworking.

The selected list on this page samples the variety while emphasizing works related to home building and repair rather than cabinetmaking. It includes some books meant for pleasure and back ground-such as the beautifully illustrated descriptions of old tools and techniques by the noted artist Eric Sloane-as well as guides for the amateur, professional monographs, formal textbooks and technical compilations.

MODERN TECHNICAL

BASIC CONSTRUCTION TECHNIQUES FOR HOUSES AND SMALL BUILDINGS SIMPLY EXPLAINED, prepared by U.S. Navy Bureau of Naval Personnel. Dover Publications Inc. New York, 1972. A no nonsense manual covering all facets of home construction from planning to painting, it includes seven chapters on carpentry and woodworking. A spartan but readable and practical reference.

CABINETMAKING AND MILLWORK. by John L Feirer. Chas. A. Bennett Co. Inc., Peoria, Ill., 1970. More than a reference work on cabinetmaking, this book includes detailed chapters on materials, design, tools and machinery, construction and finishing. Although this definitive book has more than 900 pages, a good index keeps it manageable.

CARPENTRY FOR BEGINNERS, by Charles H. Hayward. Emerson Books Inc., New York, 1969. This beginner's text , one of many books by a well known craftsman-writer, describes the basics of carpentry, such as measuring, marking, nailing, gluing and joining.

THE COMPLETE BOOK OF POWER TOOLS, by R, j. De Cristoforo. Harper and Row, New York, 1972. The classic explanation of the use of the power tools that are designed for home work shops. Clearly illustrated.

CONSTRUCTION PRINCIPLES, MATERI ALS & METHODS by Harold B. Olm. Printers and Publishers Inc. Danville, Ill. 1975. A massive volume, written for professionals, on home construction materials and techniques. It presents a staggering display of information, including sections on asphalt, plastics and wiring as well as many chapters on wood products and construction methods. Many charts, tables and diagrams.

A DICTIONARY OF TOOLS USED IN WOODWORKING AND THE ALLIED TRADES C. 1700-1970, by R. A. Salaman. Allen & Unwin, London, 1975. A catalogue of thousands of hand tools with brief descriptions of their uses. Invaluable for a tool collector and useful to amateur woodworkers.

FINE WOODWORKING TECHNIQUES, by the editors of Fine Woodworking magazine. Taunton Press, Newton, Conn., 1978. A collection of 50 articles by craftsmen who have contributed to this bimonthly magazine. Articles focus on specific woodworking problems, techniques and tools.

MODERN WOODWORKING, by Willis Wagner. Goodheart-Willcox Co., South Holland, Ill., 1974. A textbook that is widely used in secondary-school shop courses, this well-illustrated book pro vides the technical information needed in general carpentry.

THE USE OF HAND WOODWORKING TOOLS, by Leo P. McDonnell. Van Nostrand Reinhold Co., New York, 1978. Primarily a tool book that explains standard techniques. Designed as a high-school textbook, it is easy to understand.

WHAT WOOD IS THAT?, by Herbert L. Ed I in. The Viking Press, New York, 1969.

After a brief discussion of the historical uses for wood, the steps for identification of 40 commonly used woods are set forth by 14 key characteristics, such as color, grain, weight and hardness.

Wafer-thin samples of the woods are provided on the inside cover.

TRADITIONAL

A MUSEUM OF EARLY AMERICAN TOOLS, by Eric Sloane. Wilfred Funk Inc., New York, 1964. Beautifully illustrated by the author, brief but informative essays describe the uses and lore of colonial American tools.

COUNTRY FURNITURE, by Aldren A. Watson. Thomas Y. Crowell Co. New York, 1974. An intriguing account of the life style, tools and craftsmanship of early American furniture makers. Illustrated by the author, the book contains excerpts from 16th and 17th Century journals, account books and letters.

OLD WAYS OF WORKING WITH WOOD, by Alex W. Bealer. Barre Publishing Co., Barre, Mass., fourth edition, 1977. From felling a tree to turning wood on a toot-powered lathe, the techniques of pre-industrial America provide perspective on those of today.

A REVERENCE FOR WOOD, by Eric Sloane. Wilfred Funk Inc. , New York, 1965, Ballantine Books (paper). New York, 1973. Pen-and-ink sketches by the author show time-honored methods for cutting, shaping and joining pieces of wood. The text uses the tools and techniques illustrated as a vehicle to relate a chronicle of daily life in early America.

VINTAGE

CARPENTRY CRAFT PROBLEMS, by H. H. Siegele. Frederick J. Drake & Co., 1942; reprinted by Craftsman Books, Solana Beach, Calif., 1975. Fundamentals of carpentry, from using a steel square to framing and raising a wall.

ELEMENTARY PRINCIPLES OF CARPENTRY, by Thomas Tredgold. John Weales, London, 1840. Well worth a search through the library, this venerable tome includes research on timber, floor construction, domes and stressing beams. Its 50 engravings include a sketch of the roof beams in "the juvenile prison in Parkhurst on the He of Wight."

JOINERY AND CARPENTRY, edited by Richard Greenhalgh. Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons Ltd., London, 1929. Six volumes. A vintage series with engravings and photographs illustrating a broad range of topics including tool selection, and stairway and partition construction.