The productivity and fertility of the farm and plant resistance to pests and disease depend on the quality of the soil. Soil quality can be enhanced and outside inputs reduced through proper tillage, compost, cover cropping, and crop rotation. These are crucial to maintaining the high level of fertility required for the close plant spacing in a mini-farm without spending a lot of money on fertilizer.

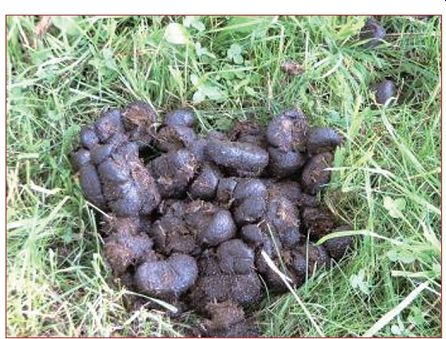

When French Intensive gardening was developed, horses were the standard mode of transportation, and horse manure was plentiful and essentially free. This explains the reliance on horse manure as a source of soil fertility. According to the Colorado State University Cooperative Extension Service, the average 1,000-pound horse generates 9 tons-18,000 pounds-of manure occupying nearly 730 cubic feet per year .

The sheer volume, smell, and mess of such quantities of manure often mean that places that board horses will give it away for the asking to anyone willing to haul it away.

------- Horse manure should be composted and not added directly to the

bed.

Horse manure is good food for crops as well. According to the same source, horse manure contains 19 pounds of nitrogen per ton, 14 pounds of phosphate, and 36 pounds of potassium. This works out to about 1 % nitrogen, 0.7% phosphate, and 1.8% potassium.

There's no such thing as a free lunch, and horse manure is no exception. Raw horse manure can spread a parasitic protozoan called giardia and E.coli as well as contaminate water sources and streams with coliform bacteria. Raw manure can also contain worm eggs that are easily transmitted to humans, including pinworms and various species of ascarid worms. Horse manure is high in salts, and if used excessively, it can cause plants grown in it to suffer water stress, even if well watered. The highest permissible rate of application of horse manure assuming the least measurable salinity is between two and three pounds of manure per square foot per year.

In addition to the above objections, horse manure doesn't have a balanced level of phosphorus, meaning that it should be supplemented with a source of phosphorus when used.

Straight horse manure is also in the process of composting. That is, the process has not yet finished. Unfinished compost often contains phytotoxic chemicals that inhibit plant growth. For horse manure to be directly usable as a planting medium, it must first be well rotted, meaning it either should be composted in a pile mixed with other compost materials such as plant debris or should at least sit by itself rotting for a year before use. The former method is preferable since that will conserve more of the manure's valuable nitrogen content. The potential problems posed by horse manure are eliminated through composting the manure with other materials first and then liberally applying the resulting compost to beds. The composting process will kill any parasites, dilute the salinity, and break down phytotoxins.

Making perfect soil from scratch, on a small scale, works quite well. The Square Foot gardening method gives a formula of 1/3 coarse vermiculite, 1/3 peat moss, and 1/3 compost by volume plus a mix of organic fertilizers to create a "perfect soil mix. " 9 My own testing on a 120-square-foot raised bed confirms that the method works beautifully. For small beds, the price of the components is reasonable. A six-inch-deep 4-foot × 6-foot bed would require only four cubic feet of each of the components. Coarse vermiculite and peat moss currently sell for about $18 for a four-cubic-foot bale.

Assuming free compost, the cost of making perfect soil mix comes to $1.50 per square foot of growing area. This works quite well on a small scale, but when even 700 square feet are put into agricultural production, the cost can become prohibitive.

Double-digging was covered in the previous section , and it is what we recommend for mini-farming. Although it is more difficult in the beginning, it affords the best opportunity to prepare the best possible soil for the money invested. No-dig beds, also described in the previous section, are a second option.

Water-Holding Capacity and pH

Few soils start out ideal for intensive agriculture or even any sort of agriculture. Some are too sandy, and some are too rich in clay.

Some are too acidic, and others are too alkaline. Many lack one or more primary nutrients and any number of trace minerals.

Soil for agricultural use needs to hold water without becoming waterlogged. Sandy soils are seldom waterlogged, but they dry out so quickly that constant watering is required. They make root growth easy but don't hold on to nutrients very well and are low in organic content or humus. (There is some dispute among experts on the exact definition of humus. For our purposes, it can be defined as organic matter in the soil that has reached a point of being sufficiently stable that it won't easily decompose further .

Thus, finished compost and humus are identical for our purposes.) Clay soils will be waterlogged in the winter and will remain waterlogged as long as water comes to them. As soon as the water stops, they bake and crack, putting stress on root systems. Clay soil is clingy, sticky, and nearly impenetrable to roots. Loam soil is closest to the ideal, as it consists of a mix of sand and clay with a good amount of humus that helps it retain water and nutrients in proportions suitable for agriculture.

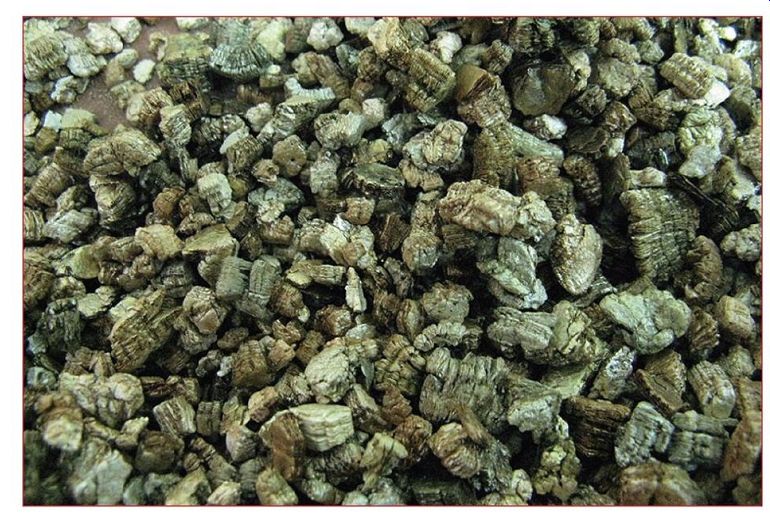

Both sandy and clay soils can be improved with vermiculite.

Vermiculite is manufactured by heating mica rock in an oven until it pops like popcorn. The result is a durable substance that holds and releases water like a sponge and improves the water-holding characteristics of practically any kind of soil. Because it is an insoluble mineral, it will last for decades and possibly forever . If the soil in your bed isn't loamy to start with, adding coarse or medium vermiculite at the rate of four to eight cubic feet per 100 square feet of raised bed will be very beneficial. (Vermiculite costs $4 per cubic foot in four-cubic-foot bags at the time of this writing.) If you can't find vermiculite, look instead for bails of peat moss.

Peat moss is an organic material made from compressed prehistoric plants at the bottom of bogs and swamps, and it has the same characteristic as vermiculite in terms of acting as a water reservoir .

It costs about the same and can also be found in large bales. It should be added at the same rate as vermiculite-anywhere from four to eight cubic feet per 100 square feet of raised bed. Keep in mind that peat moss raises the soil's pH slightly over time and decomposes, so it must be renewed.

------- Vermiculite enhances the water-holding capacity of the soil.

The term pH refers to how acidic or alkaline the soil is and is referenced on a scale from 0 to 14, with 0 corresponding to highly acidic battery acid, 14 to highly alkaline drain cleaner , and 7 to neutral distilled water . As you might imagine, most plants grown in a garden will perform well with a pH between 6 and 7. (There are a few exceptions, such as blueberries, that prefer a highly acidic soil.) pH affects a lot of things indirectly, including whether nutrients already in the soil are available for plants to use and the prevalence of certain plant disease organisms such as "club foot" in cabbage.

On the basis of a pH test, you can amend your soil to near neutral or just slightly acid, a pH of 6.5 or so, with commonly available lime and sulfur products. To adjust the pH up 1 point, add dolomitic limestone at the rate of 5 pounds per 100 square feet of raised bed and work it into the top two inches of soil. To adjust the pH down 1 point, add iron sulfate at the rate of 1.5 pounds per 100 square feet of raised bed and work it into the soil. To adjust the pH by half a point, say from 6 to 6.5, cut the amount per 100 square feet in half.

pH amendments don't work quickly. Wait 40 to 60 days after adding the amendments, and then retest the soil before adding any more. If amendments are added too quickly, they can build up in the soil and make it inhospitable for growing things.

Fertilizers

The fertility of soil is measured by its content of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, and fertilizers are rated the same way, using a series of numbers called "NPK. " The N in NPK stands for nitrogen, the P for phosphate, and the K for potassium. A bag of fertilizer will be marked with the NPK in a format that lists the percentage content of each nutrient, separated by dashes. So, for example, a bag of fertilizer labeled " 5-10-5" is 5% nitrogen, 10% phosphate, and 5% potassium.

A completely depleted garden soil with no detectable levels of NPK requires only 4.6 ounces of N, 5 ounces of P , and 5.4 ounces of K per 100 square feet to yield a "sufficient" soil. In the case of root crops, less than 3 ounces of N are needed.

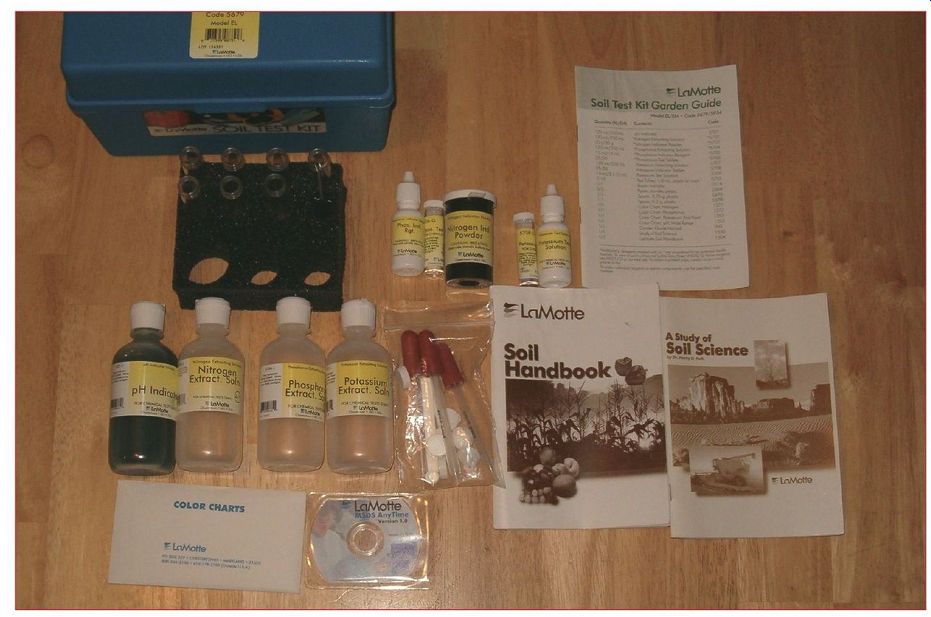

Inexpensive soil tests are available to test the pH, nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium content of soil. A couple of weeks after the soil in the bed has been prepared and compost and/or manure have been worked in, you should test the soil's nutrient content and amend it properly. The most important factor in the long-range viability of your soil is organic matter provided by compost and manures, so always make sure that there is plenty of organic matter first, and then test to see what kind of fertilization is needed.

You can buy a soil test kit at most garden centers, and most give results for each nutrient as being depleted, deficient, adequate, or sufficient. The latter two descriptions can be confusing because in ordinary English, they have identical meaning. For the purposes of interpreting soil tests, consider "adequate" to mean that there is enough of the measured nutrient for plants to survive but not necessarily thrive. If the soil test indicates the amount to be "sufficient, " then there is enough of the nutrient to support optimal growth.

The Rapitest soil test kit is commonly available, costs less than $20, and comes with enough components to make 10 tests. The LaMotte soil test kit is one of the most accurate available and can currently be purchased via mail order for less than $55. When preparing a bed, I recommend adding enough organic fertilizers to make all three major nutrients "sufficient." Organic fertilizers are a better choice than synthetic ones for several reasons. Organic fertilizers break down more slowly so they stay in the soil longer and help build the organic content of your soil as they break down. Synthetics can certainly get the job done in the short term, but they also carry the potential to harm important microbial diversity in the soil that helps to prevent plant diseases, and they also hurt earthworms and other beneficial soil inhabitants.

For these reasons, I strongly discourage the use of synthetic fertilizers.

Organic fertilizers, like synthetics, are rated by NPK, but because they are made from plant, animal, and mineral substances, they contain a wide array of trace minerals that plants also need.

Probably the biggest argument in favor of using organic fertilizers is taste. The hydroponic hothouse tomatoes at the grocery store are grown using exclusively synthetics mixed with water . Compare the taste of a hydroponic hothouse tomato with the taste of an organic garden tomato, and the answer will be clear.

There is one thing to keep in mind with organic fertilizers: Many of them are quite appetizing to rodents! One spring, I discovered that the fertilizer in my garage had been torn open by red squirrels and eaten almost entirely! Ever since, I store organic fertilizers in five-gallon buckets with lids.

-------- The LaMotte soil test kit is very accurate.

There are a number of available sources for organic fertilizers.

Some come premixed, or you can make them yourself from individual components.

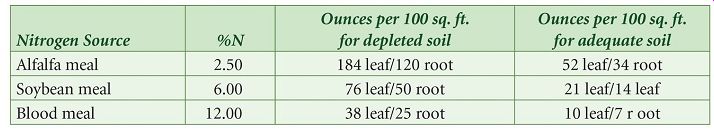

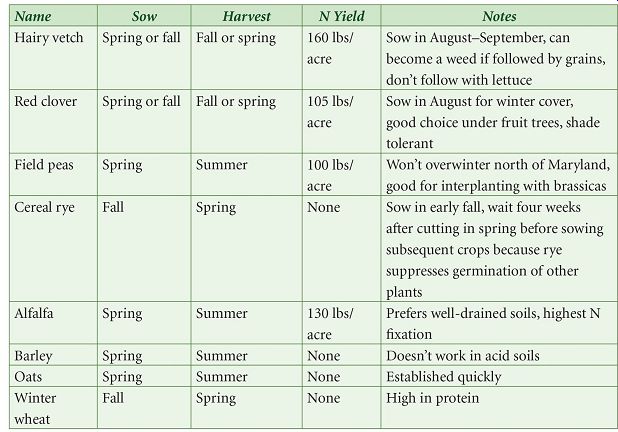

Making your own premixed fertilizer is easy. For N, you can use alfalfa meal, soybean meal, or blood meal. For P , bone meal and rock phosphate work well. For K, wood ashes, greensand, and seaweed will work. The foregoing list is far from exhaustive, but the materials are readily available from most garden or agricultural stores.

Table 1 contains two numbers notated as either "leaf " or "root" because root crops don't need as much nitrogen as leafy vegetable crops. In fact, too much nitrogen can hurt the productivity of root crops. There's also no reason to formulate a fertilizer for depleted soil since that shouldn't happen after the first year , and maybe not even then if adequate compost has been added. If it does, just add triple or quadruple the amount used for adequate soil. Looking at these tables, it should be pretty easy to formulate a couple of ready made fertilizers.

A "high nitrogen" fertilizer for vegetative crops like spinach could consist of a mix of 10 ounces of blood meal, 6 ounces of bone meal, and 21 ounces of wood ashes.

As long as you keep the proportions the same, you can mix up as much of it as you like to keep handy, and you know that 37 ounces of the mixture are required for each 100 square feet. Just a tad over two pounds.

----------- Table 1: Nitrogen Sources

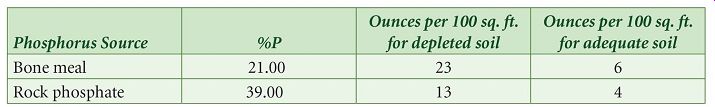

------------ Table 2: Phosphorus Sources

------------ Table 3: Potassium Sources

A "low nitrogen" fertilizer for root crops like parsnips could consist of a mix of 34 ounces of alfalfa meal, 4 ounces of rock phosphate, and 30 ounces of greensand.

Just as with the first formulation, as long as you keep the proportions the same, you can mix up as much as you'd like, and you know that 68 ounces are required for each 100 square feet-a hair over four pounds.

Your actual choice of fertilizers and blends will depend on availability and price of materials, but using a variety of components guarantees that at some point practically every known nutrient-and every unknown nutrient-finds its way into your garden beds. Wood ashes should be used no more often than once every three years because of the salts they can put into the soil and because they can raise the soil pH.

Fertilizers should be added to the soil a couple of weeks before planting and worked into the garden bed; any additional fertilizer should then be added on top of the ground as a side dressing, perhaps diluted 50/50 with some dried compost.

The reason for dilution is that some organic fertilizers, such as blood meal, are pretty powerful-as powerful as synthetics-and if they touch crop foliage directly, they can damage plants.

Liquid fertilizers are worth mentioning, particularly those intended for application directly to leaves. These tend to be extremely dilute so that they won't hurt the plants, and they are a good choice for reducing transplant shock.

In some cases, liquid fertilizers can be a lifesaver . One year , I planted out cabbage well before last frost in a newly prepared bed.

Having added one-third of the bed's volume in compost of every sort imaginable, I made the mistake of assuming the bed had adequate nutrients. What I had forgotten is that plants can't use nitrogen when the soil is too cold. A couple of days after the cabbage plants were planted, they turned yellow, starting from the oldest leaves first, which is a classic symptom of severe nitrogen deficiency.

----------- Popular organic liquid fertilizers.

As an experiment, I added a heavy side-dressing of mixed blood meal, bone meal, and wood ashes and watered it in on all the cabbage plants, but for half of them, I also watered the leaves with a watering can containing liquid fertilizer mixed according to package directions. The result was that all of the plants watered with the liquid fertilizer survived and eventually thrived, while a full half of the plants that received only a side-dressing died.

Now, I use liquid fertilizer-specifically Neptune's Harvest- whenever I transplant, especially in early spring.

Soil Maintenance

Believe it or not, soil is a delicate substance. More than merely delicate, it is quite literally alive. It is the life of the soil, not its sand and clay, that makes it fertile and productive. A single teaspoon of good garden soil contains millions of microbes, almost every one of which contributes something positive to the garden. The organic matter serves as a pH buffer , detoxifies pollutants, holds moisture, and serves to hold nutrients in a fixed form to keep them from leaching out of the soil. Some microbes, like actinomycetes, send out delicate microscopic webs that stretch for miles, giving soil its structure.

The structure of soil for intensive agriculture is maintained through cover crops (explained later in this section) to maintain fertility and prevent erosion; regularly adding organic matter in the form of left over roots, compost, and manures; crop rotation; and protecting the soil from erosion, compaction, and loosening.

Once the soil in a bed has been prepared initially, as long as it hasn't been compacted, it shouldn't need more than a fluffing with a broad fork or digging fork yearly and stirring of the top few inches with a three-tined cultivator . Digging subsequent to bed establishment is much easier and faster than the initial double-dig.

It was noted earlier that you shouldn't walk on the garden beds.

An occasional unavoidable footprint won't end life on earth, but an effort should be made to avoid it because that footprint compacts the soil, makes that area of soil less able to hold water , decreases the oxygen that can be held in the soil in that area, and damages the structure of the soil, including the structure established by old roots and delicate microbial webs. Almost all species of actinomycetes are aerobic-meaning that they require oxygen.

Compacting the soil can deprive them of needed oxygen.

The microbial webs in soil are extremely important in that they work in symbiosis with root systems to extend their reach and ability to assimilate nutrients.

Damaging these microbial webs- which can stretch for several feet in each direction from a plant- reduces the plant's ability to obtain nutrients from the soil.

My wife thought I was overreaching on this point and insisted on occasionally walking in the beds to harvest early beans, so I did an experiment. I planted bunching onions from the same packet of seeds in places where she had walked in the beds and in places where she hadn't. The results? Total yield per square foot, measured in pounds, was 20% lower in the places where my wife had walked. She only weighs 115 pounds! The lesson is plain:

Maximum productivity from a raised bed requires avoiding soil compression.

Some gardeners favor heavy duty tilling of agricultural land at least yearly and often at both the beginning and end of a season.

The problem with such practices lies in the fact that the very same aspects of soil life and structure that are disrupted by compaction are also disrupted by tilling, particularly deep tilling.

Soil amendments, such as compost and organic fertilizers, should be mixed with the soil-no doubt. But this doesn't require a rototiller . A simple three-tined cultivator (looks like a claw), operated by hand, is sufficient to incorporate amendments into the top couple of inches of soil. Earthworms and other soil inhabitants will do the job of spreading the compost into deep soil layers.

The Amazing Power of Biochar

Most of us are used to thinking of charcoal as an indispensable aid to grilling, and that it certainly is! But less well-known is its equally beneficial effect when added to ordinary garden soil. The standard charcoal you buy at the grocery store may be impregnated with everything from saltpeter to volatile organic compounds intended to aid burning, so it may not be a good choice. There are some "all natural" or even organic charcoals out there that can be used, such as Cowboy Brand Charcoal, though. In addition, some companies make charcoal specifically intended for agricultural use, such as Troposphere Energy.

Of course, if you have access to hardwood, making your own charcoal isn't terribly difficult. In fact, for agricultural use, you don't even need hardwood-just any old vegetable matter-and you can make the charcoal that is trendy nowadays to call "biochar." The benefits of biochar mixed in the soil are many and were first discovered by the peoples inhabiting the Amazon basin in pre Columbian times. They discovered that turning their vegetable matter into charcoal, pulverizing it, and adding it to the soil enhanced the soil's productivity. Soil scientists have now discovered that charcoal, previously thought to be inert in soil, lowers the soil's acidity; creates a haven for the beneficial bacteria that live in symbiosis with the root hairs of crops; helps to keep fertilizers in the soil instead of letting them be washed out, thus decreasing the need for fertilizer; and helps to loosen tight soils. In addition, it helps to sequester carbon from the atmosphere, thereby reducing global warming. More benefits are being discovered all the time.

----------- The three-tined cultivator is a workhorse for raised beds.

The easiest way to add this incredible fertilizer to your garden beds is to make it right where you want it used: in your beds. Use hoe to make a couple of one-foot-wide and six- to nine-inch-deep trenches running the length of the bed. Place dried branches, leaves and other vegetable matter neatly, but not too tightly packed, in the trenches. Then, light them on fire in several places. (Avoid using chemicals such as charcoal lighter or gasoline as these could seriously poison the soil.) Once the material is burning well and the smoke has turned gray, cover with the mounded up soil on the sides of the trenches to deprive it of oxygen, and let it smolder until the pieces are no larger than a deck of cards. Then, douse the embers with plentiful quantities of water . If you do this every fall with garden refuse and other vegetable matter , you will soon have soil that, taken together with the other practices here, will have astonishing levels of productivity.

Cover Crops and Beneficial Microbes

Today we know a lot more than our great-grandparents did about the relationship between plants and microorganisms in the soil. It turns out that the microorganisms in soil are not merely useful for suppressing diseases but actually an integral part of a plant's root system.

Up to 40% of the carbohydrates that plants produce through photosynthesis are actually transported to the root system and out into the soil to feed microorganisms around the root system. In turn, these microorganisms extend the plant's root system and make necessary nutrients available.

Friendly microorganisms grow into the roots themselves, setting up a mutually beneficial cooperation (symbiosis) and respond with natural production of antibiotics when needed to protect their host.

Planting cover crops will serve to keep these critters fed through the winter months and protected from environmental hazards such as sun and erosion. This way they are healthy and well fed for the next planting season.

For these reasons, harvesting should be considered a two-part process in which the task of harvesting is followed as soon as possible with the sowing of cover crops, which can also be known as green manures.

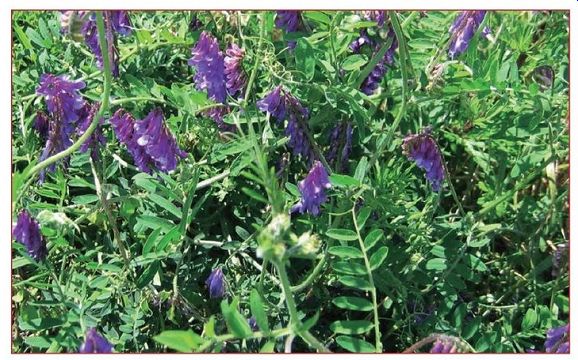

Green manures are plants grown specifically for the role they play in sustaining soil fertility, but they also reduce erosion and feed beneficial microbes outside the growing season. The benefits of green manures on crop yield are far from merely theoretical. In one study, for example, the use of hairy vetch (a common legume) as a green manure and mulch increased tomato yields by more than 100%.

Green manures are generally either grains or legumes; grains because of their ability to pull nutrients up into the topsoil from a depth of several feet, 13 and legumes because of their ability to take nitrogen out of the air and fix it in nodules in their roots, thereby fertilizing the soil. They are either tilled directly into the ground once grown or added to compost piles. Legumes use up their stored nitrogen to make seed, so when they are used as green manures, they need to be cut just before or during their flowering.

During the summer growing season, green manures should be grown in beds that will be followed by heavy-feeding plants, such as cabbage, as part of a crop rotation plan.

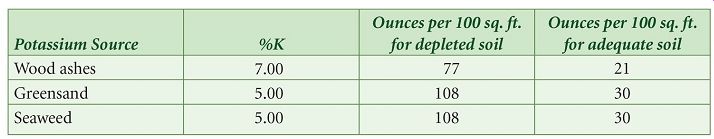

----------- Table 4 : Cover Crops/Green Manures and Nitrogen Yields

An important aspect of making a mini-farm economically viable is the use of green manures to provide and enhance soil fertility and reduce dependence on purchased fertilizers. To that end, cover crops should be grown over the winter to start the spring compost pile and should also be planted in any bed not in use to prevent leaching of nutrients and promote higher fertility. The careful use of green manures as cover crops and as specific compost ingredients can entirely eliminate the need for outside nitrogen inputs. For example, alfalfa makes an excellent green manure during the growing season in that it leaves 42 percent of its nitrogen in the ground when cut plus provides biologically fixed nitrogen to the compost pile. I recommend that 25 to 35 percent of a mini-farm's growing area should be sown in green manures during the growing season, and all of it should be sown in green manures and/or cover crops during the winter.

Green manures inter-planted with crops during the growing season can form a living mulch. Examples include sowing hairy vetch between corn stalks at the last cultivation before harvest or planting vegetables without tilling into a bed already growing subterranean clover. On my own mini-farm, I grow white clover between tomato plants.

------------ Hairy vetch is an excellent cover crop.

Cover crops aren't a cure-all, and they can cause problems if used indiscriminately. For example, using a vetch cover crop before growing lettuce can cause problems with a lettuce disease called sclerotina.

Because the increased organic matter from a cover crop can cause a short-term increase in populations of certain pests such as cutworms, it is important to cut or till the cover crop three or four weeks before planting your crops.

Legume green manures, such as peas, beans, vetch, and clovers, also need to be covered with the correct type of bacterial inoculant (available through seed suppliers) before they are sown to ensure their health and productivity.

Given these complications, how does a farmer pick a cover crop? Cover crops need to be picked based on the climate, the crop that will be planted afterward, and specific factors about the cover crop- such as its tendency to turn into an invasive weed. Legumes and grains are often, though not always, sown together as a cover crop.

Some cover crops, like oats and wheat, can also serve as food. If this is anticipated, it might be worthwhile to investigate easily harvested grains like hull-less oats. However, keep in mind that the choice of green manures will be at least partially dictated by climate.

Many crops that grow fine over the winter in South Carolina won't work in Vermont.

Crop Rotation

Crop rotation is one of the oldest and most important agricultural practices in existence and is still one of the most effective for controlling pest populations, assisting soil fertility, and controlling diseases.

The primary key to successful crop rotation lies in understanding that crops belong to a number of different botanical families and that members of each related family have common requirements and pest problems that differ from those of members of other botanical families. Cabbage and brussels sprouts, for example, are members of the same botanical family, so they can be expected to have similar soil requirements and be susceptible to the same pest and disease problems. Peas and beans are likewise part of the same botanical family; corn belongs to yet another family unrelated to the other two. A listing of the botanical names of most cultivated plant families with edible members follows:

Amaryllidaceae-leek, common onion, multiplier onion, bunching onion, shallot, garlic, chives Brassicaceae-horseradish, mustards, turnip, rutabaga, kale, radish, broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage, collards, cress Chenopodiaceae-beet, mangel, Swiss chard, lamb's quarters, quinoa, spinach Compositae-endive, escarole, chicory, globe artichoke, jerusalem artichoke, lettuce, sunflower

Cucurbitaceae-cucumber , gherkin, melons, gourds, squashes Leguminosae-peanut, pea, bean, lentil, cowpea Solanaceae-pepper , tomato, tomatillo, ground cherry, potato, eggplant Umbelliferae-celery, dill, carrot, fennel, parsnip, parsley Gramineae-wheat, rye, oats, sorghum, corn Amaranthaceae-grain and vegetable amaranth Convolvulaceae-water spinach, sweet potato Some plants will do better or worse depending on what was grown before them. Such effects can be partially canceled by the use of intervening cover crops between main crops. Thankfully, a large amount of research has been done on the matter , and while nobody is sure of all the factors involved, a few general rules have emerged from the research.

Never follow a crop with another crop from the same botanical family (e.g., don't follow potatoes with tomatoes or squash with cucumbers).

Alternate deep-rooted crops (like carrots) with shallow-rooted crops (such as lettuce).

Alternate plants that inhibit germination (like rye and sunflowers) with vegetables that don't compete well against weeds (like peas and strawberries).

Alternate crops that add organic matter (e.g., wheat) with crops that add little organic matter (e.g., soybeans).

Alternate nitrogen fixers (such as alfalfa or vetch) with nitrogen consumers (such as grains or vegetables).

The most important rule with crop rotations is to experiment and keep careful records. Some families of plants have a detrimental effect on some families that may follow them in rotation but not on others. These effects will vary depending on cover cropping, manuring, and composting practices, so no hard and fast rules apply, but it is absolutely certain that an observant farmer will see a difference between cabbage that follows carrots as opposed to cabbage that follows potatoes. Keeping careful records and making small variations from year to year while observing the results will allow the farmer to fine-tune practices to optimize quality and yields.

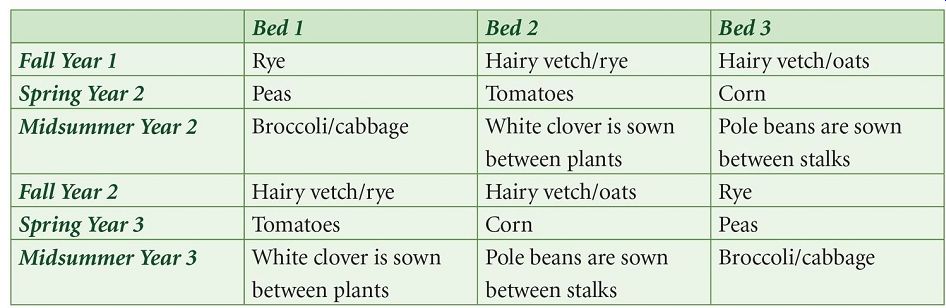

A three-bed rotation applicable to where I live in New Hampshire might give you an idea of how crop rotation with cover cropping works. We'll start with the fall.

------------- Table 5 : Example Three-Bed Rotation with Cover Cropping

----