Many homeowners undertake the task of gardening or small-scale farming as a hobby to get fresh-grown produce and possibly save money over buying food at the supermarket. Unfortunately, the most common gardening methods end up being so expensive that even some enthusiastic garden authors state outright that gardening should be considered, at best, a break-even affair.

Looking at the most common gardening methods, such authors are absolutely correct. Common gardening methods are considerably more expensive than they need to be because they were originally designed to benefit from the economies of scale of corporate agribusiness. When home gardeners try to use these methods on a smaller scale, it's a miracle if they break even over a several-year period, and it is more likely they will lose money.

The cost of tillers, watering equipment, large quantities of water, transplants, seeds, fertilizers and insecticides adds up pretty quickly.

Balanced against the fact that most home gardeners grow only vegetables, and vegetables make up only less than 10% of the calories an average person consumes, 3 it quickly becomes apparent that even if the cost of a vegetable garden were zero, the amount of actual money saved in the food bill would be negligible. For example, if the total economic value of the vegetables collected from the garden in a single season amounted to about $350, 4 and the vegetables could be produced for free, the economic benefit would amount to only $7 per week when divided over the year.

The solution to this problem is to both cut costs and increase the value of the end product. This can be accomplished by growing your own seedlings from open-pollinated plant varieties so you can save the seeds and avoid the expense of buying both transplants and seeds, using intensive gardening techniques that use less land, conscientiously composting to reduce the need for fertilizers, and growing calorie-dense crops that will supply a higher proportion of the household's caloric intake.

Using this combination, the economic equation will balance in favor of the gardener instead of the garden supply store, and it becomes quite possible to supply all of a family's food except meat from a relatively small garden. According to the USDA, the average annual per capita expenditure on food was $2,964 in 2001, with food costs increasing at a rate of 27.7% over the previous 10 years.

Understanding that food is purchased with after-tax dollars, it becomes clear that home agricultural methods that take a significant chunk out of that figure can make the difference, for example, between a parent being able to stay at home with children and he or she having to work, or it could vastly improve the quality of life of a retiree on a fixed income.

The key to making a garden work to your economic benefit is to approach mini-farming as a business. No, it is not a business in the sense of incorporation and taxes unless some of its production is sold, but it is a business in that by reducing your food expenditures, it has the same net effect on finances as income from a small business. Like any small business, it could earn money or lose money depending on how it is managed.

Grow Your Own Seedlings

Garden centers are flooded every spring with home gardeners picking out seedlings for lettuce, broccoli, cucumbers, tomatoes, and so on. For those who grow gardens strictly as a hobby, this works out well because it allows them to get off to a quick start with minimal investment of time and planning. But for the mini-farmer who approaches gardening as a small business, it's a bad idea.

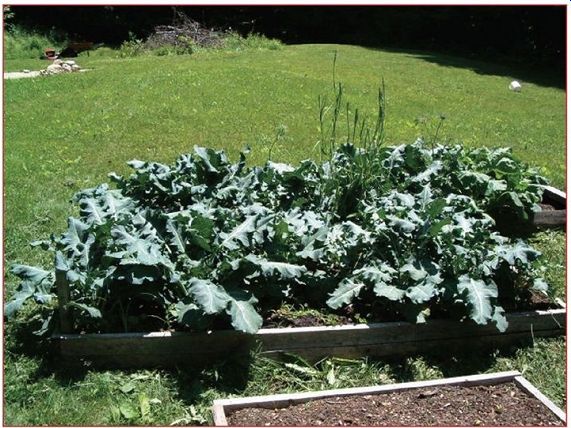

----- These broccoli plants grown from seed saved a lot of money in the

long run.

In our own garden this year , we plan to grow 48 broccoli plants.

Seedlings from the garden center would cost $18 if discounted and possibly over $30. Even the most expensive organic broccoli seeds on the market cost less than a dollar for 48 seeds. If transplants are grown at home, their effective cost drops from $18 to $30 down to $1. Adding the cost of soil and containers, the cost is still only about $2 for 48 broccoli seedlings.

Considering that a mini-farm would likely require transplants for dozens of crops ranging from onion sets to tomatoes and lettuce, it quickly becomes apparent that even if all seed is purchased, growing transplants at home saves hundreds of dollars a year.

Prefer Open-Pollinated Varieties

There are two basic types of seed/plant varieties available: hybrid and open-pollinated. Open-pollinated plant varieties produce seeds that duplicate the plants that produced them. Hybrid plant varieties produce seeds that are at best unreliable and sometimes sterile and therefore often unusable.

Although hybrid plants have the disadvantage of not producing good seed, they often have advantages that make them worthwhile, including aspects of "hybrid vigor . " Hybrid vigor refers to a poorly understood phenomenon in plants where a cross between two different varieties of broccoli can yield far more vigorous and productive offspring than either parent. Depending on genetic factors, it also allows the creation of plants that incorporate some of the best qualities of both parents while deemphasizing undesirable traits. Using hybridization, then, seed companies are able to deliver varieties of plants that incorporate disease resistance into a particularly good tasting vegetable variety.

So why not just use hybrid seeds? Because there's no such thing as a free lunch. For plants that normally self-pollinate, such as peppers and tomatoes, there is no measurable increase in the vigor of hybrids. The hybrids are just a proprietary marketing avenue. So buying hybrids in those cases just raises costs, and since the tomato seeds can't be saved, the mini-farmer has to buy seeds again the next year . The cost of seeds for a family-sized mini-farm that produces most of a family's food for the year can easily approach $200, a considerable sum! Beyond that, seed collected and saved at home can not only reduce costs but be resold if properly licensed.

(Here in New Hampshire, a license to sell seeds costs only $100 annually.) Another reason to save seeds from open-pollinated plant varieties is if each year you save seeds from the best performing plants, you will eventually create varieties with genetic characteristics that work best in your particular soil and climate. That's a degree of specialization that money can't buy.

Of course, there are cases where hybrid seeds and plants outperform open-pollinated varieties by the proverbial country mile.

Corn is one such example. The solution? Use the hybrid seeds or , if you are so inclined, make your own! Hybridization of corn is quite easy. Carol Deppe's excellent book Breed Your Own Vegetable Varieties gives all of the details on how to create your own hybrids.

Hybrid seeds that manifest particular pest- or disease-resistant traits can also be a good choice when those pests or diseases cause ongoing problems. When using hybrid seeds eliminates the need for synthetic pesticides, they are a good choice.

Use Intensive Gardening Techniques

A number of intensive gardening methods have been well documented over the past century. What all of these have in common is growing plants much more closely spaced than traditional row methods. This closer spacing causes a significant decrease in the amount of land required to grow a given quantity of food, which in turn significantly reduces requirements for water , fertilizer , and mechanization. Because plants are grown close enough together to form a sort of "living mulch, " the plants shade out weeds and retain moisture better , thus decreasing the amount of work required to raise the same amount of food.

Intensive gardening techniques make a big difference in the amount of space required to provide all of a person's food. Current agribusiness practices require 30,000 square feet per person or 3/4 acre. Intensive gardening practices can reduce the amount of space required for the same nutritional content to 700 square feet, 6 plus another 700 square feet for crops grown specifically for composting.

That's only 1,400 square feet per person, so a family of three can be supplied in just 4,200 square feet. That's less than 1/10 of an acre.

In many parts of the United States, land is extremely expensive, and lot sizes average a half acre or less. Using traditional farming practices, it isn't even possible to raise food for a single person in a half-acre lot, but using intensive gardening techniques allows only half of that lot-1/4 acre-to provide nearly all the food for a family of four , generate thousands of dollars in income besides, allow raising small livestock plus leave space for home and recreation.

Intensive gardening techniques are the key to self-sufficiency on a small lot.

Compost

Because growing so many plants in such little space puts heavy demand on the soil in which they are grown, all intensive agriculture methodologies pay particular attention to maintaining the fertility of the soil.

The law of conservation of matter indicates that if a farmer grows a plant, that plant took nutrients from the soil build itself. If the plant is then removed from the area, the nutrients in that plant are never returned to the soil, and the fertility of the soil is reduced. To make up for the loss of fertility, standard agribusiness practices apply commercial fertilizers from outside the farm.

The fertilizer costs money, of course. While there are other worthwhile reasons for avoiding the use of nonorganic fertilizers, including environmental damage, the biggest reason is a mini-farm with a properly managed soil fertility plan can drastically reduce the need to purchase fertilizer altogether , thereby reducing one of the biggest costs associated with farming and making the mini-farm more economically viable. In practice, a certain amount of fertilizer will always be required, especially at the beginning, but using organic fertilizers and creating compost can ultimately reduce fertilizer requirements to a bare minimum.

The practice of preserving soil fertility consists of growing crops specifically for compost value, growing crops to fix atmospheric nitrogen into the soil, and composting all crop residues possible (along with the specific compost crops) and practically anything else that isn't nailed down. (Section 5 covers composting in detail.) A big part of soil fertility is the diversity of microbial life in the soil, along with the presence of earthworms and other beneficial insects. There are approximately 4,000 pounds of bacteria in an acre of fertile topsoil. These organisms work together with soil nutrients to produce vigorous growth and limit the damage done by disease-causing microorganisms known as "pathogens."

Grow Calorie-Dense Crops

As already noted, vegetables provide about only 10% of the average American's calories. Because of this, a standard vegetable garden may supply excellent produce and rich vitamin content, but the economic value of the vegetables won't significantly reduce your food bill over the course of a year. The solution to this problem is to grow crops that provide a higher proportion of caloric needs such as fruits, dried beans, grains, and root crops such as potatoes and onions.

Raise Meat at Home

Most Americans are accustomed to obtaining at least a portion of their protein from eggs and meat. Agribusiness meats are often produced using practices and substances (such as growth hormones and antibiotics) that worry a lot of people. Certainly, factory-farmed meat is very high in the least healthy fats compared to free-range, grass-fed animals or animals harvested through hunting.

The problem with meat, in an economic sense, is that the feeding for one calorie of meat generally requires anywhere from two to four calories of feed. This sounds, at first blush, like a very inefficient use of resources, but it isn't as bad as it seems. Most livestock, even small livestock like poultry, gets a substantial portion of its diet from foraging around. Poultry will eat all of the ticks, fleas, spiders, beetles, and grasshoppers that can be found plus dispose of the farmer's table scraps. If meat is raised on premises, then the mini-farmer just has to raise enough extra food to make up the difference between the feed needs and what was obtained through scraps and foraging.

Plant Some Fruit

There are a number of fruits that can be grown in most parts of the country: apples, grapes, blackberries, pears, and cherries to name few. Newer dwarf fruit tree varieties often produce substantial amounts of fruit in only three years, and they take up comparatively little space. Grapes native to North America, such as the Concord grape, are hardy throughout the continental United States, and some varieties, like muscadine grapes, grow prolifically in the South and have recently been discovered to offer unique health benefits.

Strawberries are easy to grow and attractive to youngsters. A number of new blackberry and raspberry varieties have been introduced, some without thorns, that are so productive you'll have more berries than you can imagine.

Fruits are nature's candy and can easily be preserved for apple sauce, apple butter , snacks, jellies, pie filling, and shortcake topping. Many fruits can also be stored whole for a few months using root cellaring. Fruits grown with minimal or no pesticide usage are expensive at the store, and growing your own will put even more money in the bank with minimal effort.

Grow Market Crops

Especially if you adopt organic growing methods, you can get top-wholesale-dollar for crops delivered to restaurants, organic food cooperatives, and so forth. If your property allows it, you can also set up a farm stand and sell homegrown produce at top retail dollar.

According to John Jeavon's 1986 research described in The Complete 21-Bed Biointensive Mini-Farm, a mini-farmer in the United States could expect to earn $2,079 in income from the space required to feed one person in addition to actually feeding the person. Assuming a family of three and correcting for USDA reported rises in the value of food, that amounts to $10,060 per year, using a six-month growing season.

Mel Bartholomew in his 1985 book Ca$h from Square Foot Gardening estimated $5,000 per year income during a six-month growing season from a mere 1,500 square feet of properly managed garden. This equates to $8,064 in today's market. A mini farm that sets aside only 2,100 square feet for market crops would gross an average of $11,289 per year.

It is worthwhile to notice that two very different authorities arrived at very closely the same numbers for expected income from general vegetable sales-about $5.00 per square foot.

Extend the Season

A lot of people don't realize that most of Europe, where greenhouses, cold frames, and other season extenders have been used for generations, lies north of most of the United States. Maine, for example, is at the same latitude as southern France. The reason for the difference in climate has to do with ocean currents, not latitude, and latitude is the biggest factor in determining the success of growing protected plants because it determines the amount of sunlight available. In essence, anything that can be done in southern France can be done throughout the continental United States.

The secret to making season extension economically feasible lies in working with nature rather than against it. Any attempt to build a super insulated and heated tropical environment suitable for growing bananas in Minnesota in January is going to be prohibitively expensive. A simple unheated hoop house covered with plastic is fairly inexpensive and will work extremely well with crops selected for the climate.

-------- Extending the season brings two big advantages. First, it lets

you harvest fresh greens and seasonal fare throughout the year including held

over potatoes, carrots, and onions, thus keeping the family's food costs low.

Second, it allows for earlier starts and later endings to the main growing

season, netting more total food for the family and more food for market. It

also provides a happy diversion from dreary winters when the mini-farmer can

walk out to a hoop house for fresh salad greens in the middle of a snowstorm.

Understand Your Market

As a mini-farmer you may produce food for two markets: the family and the community. The family is the easiest market to understand because the preferences of the family can be easily discovered by looking in the fridge and cabinets. The community is a tougher nut to crack, and if you decide to market your excess crops, you will need to assess your community's needs.

Food is a commodity, meaning that the overwhelming majority of food is produced and sold in gargantuan quantities at tiny profit margins that are outside the reach of a mini-farmer . The proportion of crops that are grown for market cannot hope to compare with the wholesale costs of large commercial enterprises. Therefore the only way the mini-farmer can actually derive a profit is to sell at retail direct to the community or high-markup organics at wholesale.

Direct agricultural products can work, as can value-added products such as pickles, salsas, and gourmet vinegars.

Your products can appeal to the community in a number of ways, but the exact approaches that will work in a given case depend on the farmer's analysis of the needs of that community. You should keep careful records to make sure that the right crops are being grown.

The Economic Equation

According to the Federal Bureau of Labor Statistics, as of October 2005, the average nonfarm wage earner in the United States earns $557.54 per week or $28,990 per year for working 40.7 hours every week, or 2,116 hours a year . According to the Tax Foundation, the average employee works 84 out of 260 days a year just to pay taxes deducted from the paycheck, leaving the average employee $19,620.

According to the 2001 Kenosha County Commuter Study, conducted in Wisconsin before our most recent increases in fuel costs, the average employee spent $30 per week on gas just getting back and forth to work, or $1,500 per year , and spent $45 per week on lunches and coffee on the way to work, or $2,340 per year.

Nationwide, the cost of child care for children under age 5 was estimated at $297 per month for children under age 5 and $224 per month for children aged 5 to 12. This estimate is from an Urban League study in 1997, so the expense has undoubtedly increased in the meantime. Assuming a school-age child though, the expenses of all this add up so that the average worker has only $13,092 remaining that can be used to pay the mortgage or rent, the electric bill, and so forth.

------

Though there can be other justifications for adopting mini farming, including quality-of-life issues such as the ability to home school children, it makes economic sense for one spouse in a working couple to become a mini-farmer if the net economic impact of the mini-farm can replace the income from the job. Obviously, for doctors, lawyers, media moguls, and those in other highly paid careers, mini-farming may not be a good economic decision. But mini-farming can have a sufficient net economic impact that most occupations can be replaced if the other spouse works in a standard occupation. Mini-farming is also sufficiently time efficient that it could be used to remove the need for a second job. It could also be done part-time in the evenings as a substitute for TV time.

The economics of mini-farming look like this. According to Census Bureau statistics from 2003, the average household size in the United States is 2.61 people. Let's round that up to 3 for ease of multiplication. According to statistics given earlier , accounting for the rise in food prices, the cost of feeding a family of 3 now amounts to $3,210 per person, or $9,630 per year . A mini-farm that supplied 85% of those needs would produce a yearly economic benefit of $8,185 per year-the same as a pretax income of $12,200, except it can't be taxed.

That would require 2,100 square feet of space, and 10 hours a week from April through September-a total of 240 hours. This works out to the equivalent of nearly $51 per hour.

If the farm also dedicated 2,100 square feet to market crops, you could also earn $10,060 during a standard growing season, plus spend an additional five hours a week from April through September. This works out to nearly $84 per hour.

When the cash income is added to the economic benefit of drastically slashing food bills, the minimum net economic benefit of $14,920 exceeds the net economic benefit of the average job by nearly $2,000 per year.

This assumes a lot of worst-case conditions. It assumes that the mini-farmer doesn't employ any sort of season extension, which would increase the value generated, and it assumes that the mini farmer deducts none of the expenses from the income to reduce tax liability. In addition, once automatic irrigation is set up, the mini farmer needs to work only three to four hours a day from April through November . Instead of working 2,116 hours per year to net $13,092 after taxes and commuting like the average wage earner , the mini-farmer has worked only 360 to 440 hours per year to net $14,920. At the end of the workday, the mini-farmer doesn't have to commute home-because home is where the farm is, and the workday has ended pretty early.

In this manner , the mini-farmer gains back more than 1,500 hours a year that can be used to improve quality of life in many ways, gains a much healthier diet, gets regular exercise, and gains a measure of independence from the normal employment system. It's impossible to attach a dollar value to that.

For families who want to have a parent stay at home with a child or who want to home school their children, mini-farming may make it possible-and make money in the process, by having whichever parent who earns the least money from regular employment go into mini-farming. For healthy people on a fixed income, it's a no brainer.