AMAZON multi-meters discounts AMAZON oscilloscope discounts

The majority of preventive and planned maintenance work is performed while the manufacturing plant is in operation. Major maintenance work, or work that, because of its scope, cannot be performed while the plant is operating, will be required at some point. Entire production lines (equipment systems) will need to be shut down for major equipment overhaul or even replacement. This shutdown is referred to as a Maintenance Outage.

While it may be possible to just shut down that portion of the plant needing attention, the work is normally too disruptive to continue operating.

Additionally, labor assets to perform the daily maintenance work in the operating portion of the plant will be in short supply. Thus, the maintenance outage most often involves a total plant shutdown. Economically, the total plant shutdown also makes the most sense. It is far less expensive to simultaneously shutdown all plant operations to perform major maintenance work on all plant equipment needing it than it is to conduct more frequent shutdowns in separate areas of the plant. This is referred to as a Plant Maintenance Shutdown or Plant Shutdown. One last bit of terminology is that which is applied to the process of performing the major maintenance, equipment upgrade action and/or the addition of new or expanded production capabilities. This actual execution and completion of the outage work is often referred to as a Plant Turnaround or just Turnaround.

Plant shutdowns to perform major maintenance work are the most expensive of all maintenance projects not only because of the loss of production, but also due to the expense of the major maintenance being performed. Industry surveys report that between 35 and 52% of maintenance budgets are expended in individual area or whole plant shutdowns. These figures reflect only the price of maintenance and do not encompass the lost opportunity costs of no production.

Shutdowns are a time of accelerated activity, with numerous vendors, contractors, and heavy equipment engaged in multiple tasks in close quarters. From 1995 through 2000, Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) records show that more than 25% of lost time accidents for any given year in manufacturing plants occur during major maintenance outages. Plant shutdowns can be complex, not only due to the nature of the work to be performed, but also because of the pressure to try to force as much work as possible into as short a shutdown period as possible. As the volume of work increases, the complexity of the maintenance outage increases, rendering the shutdown even more costly and, perhaps even more important, exceedingly more difficult to manage.

A plant shutdown always has a negative financial impact. This negative impact is due to the combined effect of the loss of production (sales) revenue together with the additional expenses associated with the major maintenance work. There is an overall positive return that is not always obvious to everyone, especially in the heat of battle and the steadily increasing pressure to get the work completed in the shortest time possible. The positive impacts are an increase in equipment asset reliability, continued production integrity, and a reduction in the risk of unplanned failure and resulting unplanned outages.

A major maintenance outage (total plant shutdown) is generally short in duration and high in intensity. It can cost (combined maintenance and lost production costs) as much as an entire year's maintenance budget in four to five weeks. Because the maintenance outage is the major contributor to plant downtime and maintenance costs, proper shutdown management is critical to minimizing the impact on the bottom line. "'Failure to plan is planning to fail." No single strategy is more important, or more often neglected or overlooked, than planning. Planning for and managing a maintenance outage in the manufacturing plant environment are difficult and demanding operations. If not properly planned, managed and controlled, companies run the risk of serious budget overrun and costly schedule delays. The Planning and Scheduling operations are central to completing an outage within budget and on schedule. Early identification of, or even the potential of, a problem relating to any element of the outage schedule, is the key to success and it is in the hands of planning and scheduling. Beginning the outage with a viable schedule, complete work packages and both material and personnel resources arranged for and available for contracted work as well as in-house efforts are the primary of all prerequisites necessary for success in executing the plant shutdown for major maintenance.

1. PLANNED OUTAGES DEFINED

The management and control of a planned maintenance outage, a plant shutdown and turnaround, can be broken down into five phases of activity.

They are: I. Definition II. Planning III. Scheduling IV. Execution V. Debrief and Lessons Learned

1.1 Phase I: Definition

During the Definition Phase, plant management must determine and then fully define the objectives of the plant shutdown. Critical issues that need to be addressed include:

--development of a Plant Shutdown Vision and Shutdown Objectives;

--start and duration of the plant shutdown;

--who will manage the turnaround;

--what equipment is to be involved;

--is equipment to be refurbished, completely torn down and rebuilt, or replaced?

--is new equipment, providing expanded capability/capacity, to be installed and, if so

--- has Reliability Engineering performed maintainability/reliability analyses?

--- has new equipment/vendor been identified and procurement actions initiated?

--what work will be contracted for and what work performed in-house?

--has the work and the objectives been prioritized?

--have time and cost constraints been established, i.e., work cutoffs?

When the Outage Manager has been designated, he should immediately take steps to appoint an Outage Scheduling Coordinator. In smaller plants, the outage manager and schedule coordinator will very likely be the same person.

In larger plants, and during broadly scoped shutdowns in smaller plants, the Outage Manager should meet and negotiate with the Maintenance Manager to designate a separate Outage Scheduling Coordinator and an Outage Committee consisting of at least one supervisory level maintenance person, one Reliability Engineering engineer and one senior maintenance, or MRO, storeroom person.

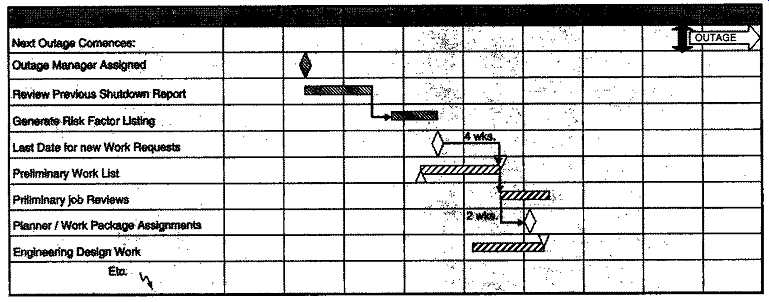

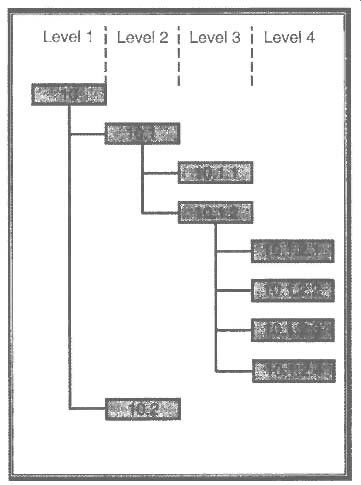

FIG. 1 POA&M for Outage Planning Period

Planning, or pre-planning, for a maintenance outage should start as soon as the current outage is completed. Too often, planning is not begun until two or three months prior to commencing work and, more often than not, involves only the writing of job specifications or procuring material and parts. Much more needs to be accomplished during both the definition phase and the second or planning phase. The first efforts should be directed toward developing a Plan of Action and Milestones (POA&M) for the pre-shutdown period--planning for the shutdown planning effort.

The pre-shutdown POA&M is a Gantt Chart (refer to Section D for a brief Gantt Chart tutorial) schedule of major events and the time frames when specific actions or evolutions must be achieved or completed prior to starting work. A "Rolling Wave" approach to pre-shutdown management is necessary. This approach involves the definition of greater and greater detail as the POA&M milestone events are completed. A partial POA&M is illustrated in FIG. 1. Milestones that should be identified, for example, should include:

[

Time Frame (days prior to start)

200-150 150-100 120-90 90-80 90-80

85-75 80-70 75-70 70-55 65-50 60-50 55-45 50-40 45-35 45 45 40 30 25 15 14-10 10 7 5

]

[

Activity--Event

Review last shutdown debriefing report and nonscheduled shutdown summary reports for the past 12 months All work requests due Preliminary work lists completed Preliminary job review meetings Assignment of Planner / Work Package pairings

Engineering design work completed Completion of planned work estimates Management review of (final) planned work estimates/Final work package definition Completion of planned work packages Shutdown parts, material, equipment ordered/ contracts placed Master job package completed and published Master job package review meetings Job sequence and assignment schedules completed Critical path network schedule completed Initial area bar charts developed Manpower requirements lists and leveling charts completed Delivery dates for major equipment procurements established Final schedule completed and issued Schedule review meetings Shutdown materials received, marked and locked up Outage coordination meeting(s)

Shutdown management booklets published Daily crew assignment board set up Preliminary work begins (tags prepared, routing marked, etc.) Initial staging of parts completed Plant shutdown

]

The shutdown must reflect the business goals of the organization. The vision is the ultimate goal towards which the outage manager orchestrates the shutdown plan. Within the shutdown plan, objectives and expectations must be established early for the entire operation. Objectives should be concise and measurable as well as applicable to each phase of the shutdown and reflect the outcome established by the vision. Some typical objectives include:

--limit new or growth work to less than 5% of total shutdown work;

--65% (or more) of shutdown work (less new capital project work) will be determined by inspection and condition monitoring versus historical data;

--zero safety incidents by contractors or plant work force, etc.

1.2 Phase II: Planning

The planning phase of a planned outage involves many of the activities seen in planning during normal plant operations, just on a different scale.

Additionally, the planner will be involved in several activities that are not necessarily part of his or her normal routine. In-house maintenance projects must be planned for with complete work packages, including major material items such as replacement equipment, equipment modification designs and material, complete overhaul kits, equipment/system interface work (i.e., piping, electrical service, etc.). Additionally, outside support services for in-house work are often required, including items such as vendor technical reps, transportation, handling and rigging services beyond in-house capabilities, etc.

[

*Although these are contracting/purchasing responsibilities, it is important that planners be involved in contract review (for work scope) and in review of outage procurements in order to identify gaps between contracted work and in-house planned support and to compare work package equipment and materials lists with purchasing outage procurements.

**The planner's cost estimates, based on completely planned work and material costs, are an order of magnitude more accurate than estimates made by management during Phase I. These estimates must be provided to management as early as possible, in order to make a determination of whether to modify the original budget, add or delete major maintenance work or change the plant shutdown duration.

]

Delivery of required material to the job site should be planned just prior (JIT) to work commencing. This eliminates transit time and loitering by the work force and increases time on tools for each trade/craftsman associated with that particular job. Additional planning considerations that are outage specific include:

--Has space been designated, footprints identified and interfacing services planned/prepared for new installations?

--Is adequate access for heavy equipment available and movement routes identified?

--Has work scope been fully defined for contracted work and are contracts executed?*

--Have housekeeping activities been factored into each work package?

--Have work package process documents been provided to maintenance (reliability) engineering so that they can develop equipment test plans?

--Has procurement of new equipment, major materials and outside support services--including defined delivery dates--been completed?*

--Collate the planned costs of the turnaround and provide estimates to management**

The scope of work and individual work packages for a major maintenance outage is much different from the scope of backlog work packages. For example, if older production equipment is to be replaced with new equipment, dismantling and removal of the old equipment must be completed prior to delivery of the new equipment to the installation site. The planner must carefully analyze each outage work project to identify which job activities must be completed prior to the start of follow-on activities in the work project. These work-precedence relationships between various job activities must be clearly defined. If they are not well defined, effective scheduling of labor resources will be impossible. Finding out, while in the midst of working on an outage project, that some prerequisite work must be performed before they can proceed could result in a maintenance crew sitting idle for several hours----even as long as several days!

Turnaround Checklist for Planners

1. Determine the general scope of turnaround work from engineering schedule and from previous preventive maintenance performed during shutdown.

2. Determine general labor resource requirements and contract labor.

3. Determine the general number of supervisors required.

4. Submit recommendations for required labor and supervisors.

5. Determine equipment that will be required, such as cranes, large quantities of scaffolding, compressors, welding machines or torque wrenches, etc., and if they will be available.

6. Determine status of materials, such as valves, internals, etc., and that they will arrive in sufficient time for checkout prior to use.

7. Determine pre-turnaround work for the project or other work and have work orders issued.

8. When the general scope of the turnaround is fairly stable, draw up a schedule for use at first meeting and to determine work force requirement.

9. When work force has been determined, write requests for labor.

10. Write request for equipment required that will have to be rented.

11. Write request for labor supervisors if applicable (timekeeping, etc.)

12. Submit personnel requisition for turnaround clerk as applicable.

Note: This should be done several weeks before needed to allow for approval and recruiting.

13. Request copy machine as applicable.

14. Request additional phones; one for supervisor area, one for materials use and one in material trailer.

15. Have desks, chairs and tables moved in for coordinator, materials and zone supervisors.

16. Order portable toilets (early) if required.

17. Submit letter of request to safety for safety orientation of contract and crews and make appointments,

20. See that material and tool trailers are properly supplied.

21. See that room and transportation arrangements are made for supervisors when there is a change. Change request submitted to senior supervisors.

22. Produce schedule. Distribute at turnaround meeting. Distribute final schedule as per distribution list.

23. See that PM work orders are produced. May have to initiate work orders.

24. Assemble work orders.

25. See that an objective for the turnaround is written and that it is given to production along with copies of all work orders.

26. Produce readable copies of all work orders for trade supervisors to be included in packet to supervisors.

27. See that all work orders are activated and that all planning, including materials, is completed.

28. Arrange for transportation for crews as applicable (confer with trade supervisors).

29. Arrange with production for an area for lay-down of surplus equipment.

30. Arrange for an extra dumpster for waste.

31. Periodic update on status of preparation work and planning.

32. Provide a telephone and beeper list of personnel for the shutdown along with other frequently used numbers.

33. Secure a list of contract workers.

34. Provide a typewriter, forms and office supplies for turnaround office.

35. Secure forklift if required.

1.2.1 Purchasing: Plant Shutdown Logistics

Acquiring the parts and materials necessary to ensure shutdown success is generally a divided or fractured activity at most plants. Maintenance, production, procurement and even engineering have traditionally had a role in "chasing parts." By establishing an integrated and scheduled material management effort, accountability and systematic updates and reporting can be established in the months leading up to the shutdown. This ensures that all required material is ordered, delivery arranged according to scheduled progression and nothing is misplaced or lost. The procurement effort then becomes integral to logistics management. Procurement managers are often promoted on their ability to get things done at the lowest possible price without regard for the possible cost. For procurement specialists, parts vendors, material suppliers and contractors competing with one another is the best of all possible worlds because it lowers the price of the item or service.

However, cheaper is not always better. This has been proven repeatedly by Total Productive Maintenance (TPM), Lean Manufacturing and Reliability-Centered organizations over the last 15 years. Nonetheless, the influence of lowest price continues to dictate many procurement efforts.

Key to successful shutdowns is establishing preferred provider relationships early in the planning process. Determine which contractors have the best record for successful execution of shutdowns, those that have proven work processes and integrated planning and scheduling procedures. Analyze which contractors have the best safety records, the lowest rework statistics and the most responsive supervisors. Once you have identified contractors that meet your criteria for partnership, invite them early into the planning process.

Do not jam up the loading dock. Sequence the delivery and distribution of material to match schedules as well as to ensure labor and storage space while checking for applicability, bagging and tagging for further distribution to staging areas. Construct a logistics distribution diagram (an overhead drawing of all routes and distribution or staging areas) and map out the flow of material. Bag or palletize peripheral material and parts (nuts, bolts, welding rod, gasket material, etc.) by work order number and supervisor.

Sequence these bagged items with the major assemblies with which they will be used.

Pre-stage large assemblies at a site central to the units to be worked on.

Generally, the plant warehouse is too remote from the work area to be considered a central site and has limited access. Choose a site that can be sheltered with multiple accesses and easy, but controlled, accessibility. Lay out an entrance and exit plan.

1.3 Phase III: Scheduling

The scheduling phase of the maintenance outage can be the success or failure determinant of the plant turnaround. The scheduler must begin his activities while the planning phase is still in progress. In plants where planning and scheduling are performed by the same person, coordination of these efforts is straightforward. Where the planners and schedulers are separate people, a continuous dialog must be established between them to ensure complete and accurate integration of their efforts. Applying traditional project management techniques for sequencing, monitoring, executing and controlling the progress of the shutdown can identify various scheduling, resources, and cost questions such as:

--Is the amount of work doable within the allotted period?

--What are the critical path jobs for completing the shutdown on schedule?

--Have enough resources (personnel, time, money) been allocated?

Beginning with the prioritized work list, the scheduler must:

-- determine if the work can be completed by the established cutoff date;

-- identify when new equipment, major materials and outside support services must be on site;

-- sequence work so that all in-house resources are utilized all the time and identify resource augmentation requirements;

-- weigh priority against job duration; it is often advisable to start longer duration jobs earlier than high-priority jobs.

Traditionally, plant shutdowns to accomplish major maintenance leave significant slack for production personnel. In the worst case, they are often faced with forced leave. In the Lean Manufacturing plant, many production line operators have been trained in performing some level of maintenance.

Additionally, operations personnel, whether trained in maintenance or not, are valuable assets because they are familiar with the equipment and systems that they operate, know the plant layout, are familiar with the organizational structure and processes and, in general, possess knowledge that can be of benefit during the maintenance outage. Early in the outage-scheduling phase, schedulers should meet with operations supervisors to identify operations department resources, skills and availability. The scheduler must then integrate the available operations resources with maintenance resources to develop and staff planned work schedules. Often a skilled maintenance tradesperson can be freed-up for other work through assignment of a minimally trained line operator, who is able to perform general-purpose work following the guidance of other team members. Available maintenance staff can provide much wider job coverage when augmented by production personnel in this manner.

The scheduler must carefully consider the work location factor during schedule development. In the rush to accomplish the many tasks involved in a shutdown, schedulers often do not take into account the physical location of the work to be performed. Pipefitters are welding above millwrights, who are working above electricians working in exposed electrical panels. Such a situation provides no mechanism for the prevention of injury or damage to equipment and work is slowed while one maintenance team waits for another team to complete a conflicting activity. Schedulers who are not familiar with an area of the plant in which they are scheduling work must perform a walk-through of the area to familiarize themselves thoroughly with equipment and support system locations.

No area is more neglected during maintenance outages than clean up, before, during and after a specific job assignment. The ability of technicians to work safely and efficiently, to prevent contamination of bearings and gears, and to ensure the safe, on-time start-up of equipment are all directly related to the cleanliness of the work area before, during and after a job.

Planners and schedulers alike must factor housekeeping activities into every job. If contracted work does not include maintenance of work area cleanliness (it should) within the scope of work, then in-house resources will need to be allocated to the task.

The final step in the wrap-up of any work package is test and inspection.

Responsibility is assigned to one individual to inspect gears and bearings before closing to ensure no foreign objects or contamination have been left behind. Once inspected and closed, such closings should be sealed with a tamper-proof seal that will evidence unauthorized entry and the need for re-inspection. Electricians and instrument technicians make a final check of connections, proper rotation and fusing. As part of the shutdown work schedule and management plan, a test plan should be developed for all equipments prior to start up, not just those machines that were worked on.

System level and interfaces, as well as individual equipment, must be tested to ensure complete restoration of services. The test plan is a responsibility of Reliability Engineering. In order to expedite development of the test plan, Maintenance Planners should provide engineering with each work package's procedural documentation. As the outage schedule is developed, the maintenance scheduler and reliability engineer will need to coordinate the scheduling and performance of the test plan requirements.

In summary, the maintenance outage considerations that schedulers will need to act on include:

--resource levels and time frame adequacy to complete the outage work package;

--logistics coordination with work schedule (material and equipment de livery/staging);

--integration of production resources with maintenance resources for work package execution;

--schedule analyzed for work location conflicts;

--essential housekeeping efforts provided for in the shutdown schedule;

--test and inspection requirements (Test Plan) factored into shutdown schedule.

1.4 Phase IV: Execution

The execution phase of the maintenance outage is the validation of the Planner's work packages and the Scheduler's work assignments and schedules. The first step of the execution phase, actually the final prerequisite for execution, is the Maintenance Outage Coordination Meeting. Structured much like the weekly maintenance schedule coordination meeting, this meeting is likely to last at least one full day and perhaps more. The Outage Coordination meeting should be conducted approximately one to two weeks prior to the commencement of the scheduled shutdown. All Maintenance, Production and Purchasing/Stores management and supervisory personnel should attend. Attendees should have been provided with the Outage Major Milestones Gantt Chart as well as individual project schedules applicable to each attendee at least 3 to 4 days prior to the meeting. The objectives of the Outage Coordination meeting are basically the same as those for the weekly production/maintenance coordination meetings. Any special requirements for work to be performed should be identified during the coordination meeting and not when the job starts. Similarly, any potential or actual logistics problems not yet resolved must be identified (e.g., supplier notification of parts/material non-availability, contracts still awaiting negotiation, etc.). Today's project management software programs are capable of utilizing several common project management methodologies such as Critical Path Method (CPM) or Project Evaluation and Review Technique (PERT). Computer technology enhancements for these classic techniques allow the shutdown scheduler a simple way to provide management with graphic presentations, resource allocation and leveling, calculating costs, communicating and delegating tasks, updating project status, reporting and analyzing "what-if" scenarios. During the execution phase, the scheduler must review work progress and work schedules several times a day. Especially important are critical path jobs (see Section 2 later in this section for an explanation of the Critical Path Method of scheduling and Section D for a more thorough CPM tutorial). Any perturbations to the work schedule must be identified as early as possible so that adjustments can be made prior to the need to drop one or more work items.

The role of the supervisor in the successful execution of a shutdown cannot be over-emphasized. Once all planning, scheduling, pre-staging and paperwork are complete, the supervisor must make the shutdown a reality.

Supervisors, whether from the plant work force or contractor, must be trained in exactly what is expected of them. Specific roles and responsibilities applicable to the shutdown organization must be communicated. Work crews should be assigned based on the optimal span of control. Generally, each supervisor should be responsible for no more than 15 to 20 workers.

This allows for hands-on interaction and follow-up on all jobs assigned to that crew.

1.5 Phase V: Debrief and Lessons Learned

The last phase and also a key element of shutdown success is also the first step in ensuring that your next shutdown is even more successful. Once the production equipment has been tested, equipment started up and product is rolling off the lines, it is human nature to breathe a sigh of relief and not think about shutdowns until the next time. It is also, just at this moment, when all of the successes and problems of the maintenance outage are still clear in everyone's mind, that a post-turnaround analysis and critique must be carried out.

The shutdown critique is a formal undertaking designed to root out what went right so it can be repeated, as well as what went wrong so it can be eliminated. The shutdown management plan brings together all the individual contributors to the shutdown. The critique phase reviews each player's contribution. Survey data can be collected from contractors and vendors. The managers and supervisors can interview plant work force and interpret performance data from the CMMS' shutdown project measures of performance reports. Questions that can be used to analyze the shutdown include:

--what issues helped or hindered shutdown performance?

--what was your evaluation of the shutdown organization and key staff?

--how was productivity measured? what data did you collect?

--how was performance measured? what data did you collect?

--did you meet all shutdown goals and objectives?

2. CRITICAL PATH METHOD SCHEDULING

One of the more important tools available to the Scheduler during a maintenance outage is the Critical Path Method (CPM) of scheduling. Whether computer automated or performed manually, CPM is the quickest and most accurate method available for scheduling and managing large, complex work packages, optimizing schedules and for modifying schedules when disruptions occur. CPM scheduling is a graphical technique used for illustrating activity sequences, together with each activity's expected duration, to portray project execution steps in precedence order.

During many large overhaul and outage situations, a project or job may consist of a number of activities that can be carried out simultaneously. The effect of doing several activities at the same time is to reduce the total time for the job to be completed. The total man-hours involved will however remain substantially the same. By tracing the various work element paths from project start to project completion, the most time-consuming path is the length of time it will take to complete the job. It is identified as the critical path because any delays along that path will delay the entire project.

Development of a CPM schedule begins by representing the project graphically by a network built up from either circles or squares and lines or arrows, which lead up to or emerge from the circles or squares. Depending on the method used, the circles or squares represent either activities or events (the completion of an activity). Connecting the circles or squares with lines or arrows represents a sequence of activities in which each one is dependent on the previous one. In other words, one activity must be completed in order to begin the next activity. The initial network development is the most important and difficult in developing CPM schedules. Graphing out the job activities and dependencies to develop the network requires intimate knowledge of the constituent parts of the project. It is remarkable how many projects are undertaken which have not been "thought through" and many persons undertaking CPM for the first time are astonished at their own ignorance of the project they are planning.

The original development of CPM scheduling technique was preceded by a very similar technique known as the Program Evaluation and Review Technique or PERT for project scheduling. Although the terms PERT and CPM today are used interchangeably, or even together as in PERT/CPM, there are in fact some subtle differences between the two methods. PERT is also known as the Activity-on-Arc (AOA) network scheduling structure.

PERT became popular after it was developed and used for management of the U.S. Navy Polaris Fleet Ballistic Missile (FBM) program. It was notable in that it brought the program in within budget and 18 months ahead of schedule. Shortly thereafter, the DuPont company introduced the CPM for managing the construction and repair of its manufacturing plants. CPM utilizes the Activity-on-Node (AON) representation as opposed to the PERT AOA structure. The characteristics of the two are:

AON

--Each activity is represented by a node in the network.

--A precedence relationship between two activities is represented by an arc or link between the two.

--AON may be less error prone because it does not need "dummy" activities or arcs.

AOA

--Each activity is represented by an arc in the network.

--If activities A and B must precede activity C, there are two arcs, A and B, leading into arc C. Thus, the nodes, the points where arcs A and B join arc C, represent events or "milestones" rather than activities (e.g., "finished activities A and B"). Dummy activities of zero duration may be required to represent precedence relationships accurately.

--AOA historically has been more popular, perhaps because of its similarity to Gantt Chart Schedules used by most project management software.

A brief example will illustrate the subtle differences in the two methods.

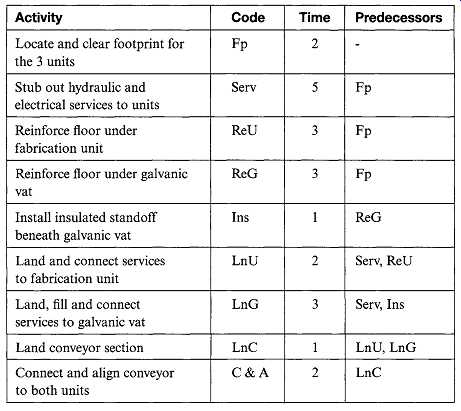

Suppose the project to be managed is the installation of a new production processing system consisting of a large, 15-ton automated metal forming and joining unit outputting to a 40-ft long steel roller conveyance, where the unit is cleaned and prepared for galvanizing, that feeds a heated (to 850-- galvanic coating vat. The project steps for installation are determined to be (greatly simplified for the sake of this example) as shown in Table 1.

When depicting AOA or PERT graphics, the custom is to identify the activity above the activity line and the duration below the activity line.

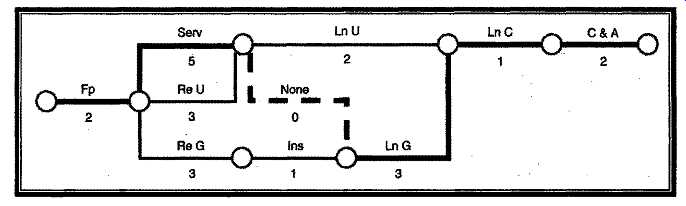

Therefore, the project defined in Table 1 when represented by an Activity-on-Arc network yields the diagram shown in FIG. 2.

Table 1 Steps in Sample Project

FIG. 2 Activity-on-Arc (AOA) Network Diagram

Note the dotted line leading into the activity line "LnG." Table 1 indicates that activities Serv and Ins are immediate predecessors of activity LnG but Serv time has already been accounted for between activities Fp and Ln U. Therefore, in order to depict the paths accurately, the dummy activity labeled

None with duration of 0 must be added to the figure. In this case, it is critical to show the dummy activity because it is in the critical path for completion of this project. The critical path in FIG. 2 is represented by double lines.

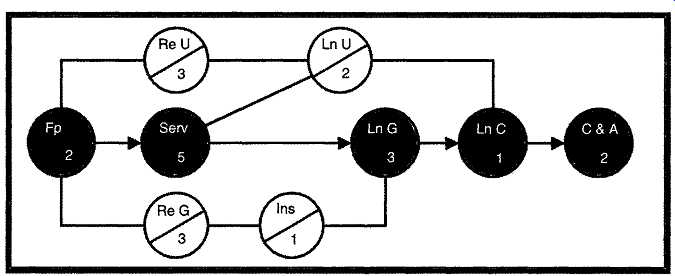

When depicting activities on an Activity-On-Node or CPM networks, the activities and their duration are shown inside the node. The same project from Table 1, when depicted as an AON network yields the diagram shown in FIG. 3. There are a number of different conventions for depicting the critical path on CPM networks. FIG. 3 illustrates several of them, however only one need be used. Node connectors with arrowheads, nodes with double lines, different color nodes and different color lettering are all shown here.

Looking again at FIG. 3, tracing the path Fp --- Serv --- LnG, you see that LnC cannot occur before day 10. Alternatively, if you trace the path to LnC as Fp --- ReG --- Ins --- LnG, you see that it requires only 9 days.

Looking at this second, shorter path, you can see that any activity not in the first, or critical, path can be delayed up to one day without impacting the start of LnC. This is called "float" or job slack. Float defines when and for how long it may be possible to divert resources to another job. Such diversion should be approached with extreme caution because the likelihood of two jobs precisely following their planned durations and/or meeting their planned start dates is very low. However, float does define points where the scheduler might look during the outage for labor resources to meet emergent, short-term needs.

FIG. 3 Activity-on-Node (AON) Network Diagram

To facilitate the use of CPM, creation of a shorthand notation scheme is advisable so that longer, descriptive phrases would not need to be written into the symbols used in CPM scheduling. The Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) is the most common tool used to create this shorthand notation. The WBS is a hierarchic breakdown of a planned work package into successive levels, each level being a further breakdown of the preceding one. Each item at a specific level of a WBS is numbered consecutively (e.g., 10, 10, 30, 40, 50) and each item at the next level is sub-numbered using the number of its parent item (e.g., 10.1, 10.2, 10.3, 10.4). The WBS may be drawn in a diagrammatic form (if automated tools are available) or in a tree-form resembling a Microsoft Windows TM folder-file tree.

The WBS begins with a single overall task (level 1) representing the totality of one planned work package. FIG. 4 illustrates a maintenance job (10) with 2 level 2 tasks (10.1 and 10.2), one of which (10.1) has 2 level 3 tasks (10.1.1 and 10.1.2), one that has no subtasks and a second one (10.1.2) that has four sub-tasks (10.1.2.1 through 10.1.2.4). In larger plants, the small investment cost for CPM scheduling software will be returned many times over in saved time for schedulers. Many CPM-based project management programs provide a variety of options for depicting WBS, CPM Network layout and even the node format and node data contents. In FIG. 5, for example, the CPM Node can contain as many as seven data fields. These programs will automatically depict critical paths and some will generate an entire shutdown schedule once the individual projects or jobs have been set up.

FIG. 4 Simple Work Breakdown Structure (WBS)

FIG. 5 CPM Node Data Contents

Once the critical path length for a project has been identified, the next question invariably asked is, "can we shorten the project?" The process of decreasing the duration of a project or activity is commonly called crashing. For many construction projects, it is common for the customer to pay an incentive to the contractor for finishing the project in a shorter length of time. For major maintenance work, it may be possible to shorten the duration of an activity by allotting more resources to it, adding an extra shift or even procuring a different unit to accomplish the job's objectives. Whenever consideration is given to "crashing" a critical path task, a careful cost analysis of the alternatives involved must be performed. The cost savings of shortening the plant shutdown by one day may, or may not, offset the cost of an additional shift for 3 or 4 days. Make informed decisions. Refer to Section D for a brief, but more detailed, tutorial on construction, analysis and utilization of graphical scheduling techniques with Gantt Charts and CPM Diagrams.

PREV. | NEXT | Article Index | HOME