AMAZON multi-meters discounts AMAZON oscilloscope discounts

Prev.

RESPONSIBILITIES

Too many maintenance functions continue to pride themselves on how fast they can react to a catastrophic failure or production interruption rather than on their ability to prevent these interruptions. Although few will admit their continued adherence to this break down mentality, most plants continue to operate in this mode. Contrary to popular belief, the role of the maintenance organization is to maintain plant equipment, not to repair it after a failure. The mission of the maintenance department in a world-class organization is to achieve and sustain optimum availability, optimum operating condition, maximum utilization of maintenance resources, optimum equipment life, minimum spares inventory, and the ability to react quickly.

Optimum Availability

The production capacity of a plant is partly determined by the availability of production systems and their auxiliary equipment. The primary function of the maintenance organization is to ensure that all machinery, equipment, and systems within the plant are always online and in good operating condition.

Optimum Operating Condition

Availability of critical process machinery is not enough to ensure acceptable plant performance levels. The maintenance organization must maintain all direct and indirect manufacturing machinery, equipment, and systems so that they will continue to be in optimum operating condition. Minor problems, no matter how slight, can result in poor product quality, reduced production speeds, or other factors that limit overall plant performance.

Maximum Utilization of Maintenance Resources

The maintenance organization controls a substantial part of the total operating budget in most plants. In addition to an appreciable percentage of the total-plant labor budget, the maintenance manager often controls the spare parts inventory, authorizes the use of outside contract labor, and requisitions millions of dollars in repair parts or replacement equipment. Therefore, one goal of the maintenance organization should be effective use of these resources.

Optimum Equipment Life

One way to reduce maintenance cost is to extend the useful life of plant equipment.

The maintenance organization should implement programs that will increase the useful life of all plant assets.

Minimum Spares Inventory

Reductions in spares inventory should be a major objective of the maintenance organization; however, the reduction cannot impair the ability to meet goals 1 through 4.

With the predictive maintenance technologies that are available today, maintenance can anticipate the need for specific equipment or parts far enough in advance to purchase them on an as-needed basis.

Ability to React Quickly

All catastrophic failures cannot be avoided. Therefore, the maintenance organization must maintain the ability to react quickly to unexpected failures.

THREE TYPES OF MAINTENANCE

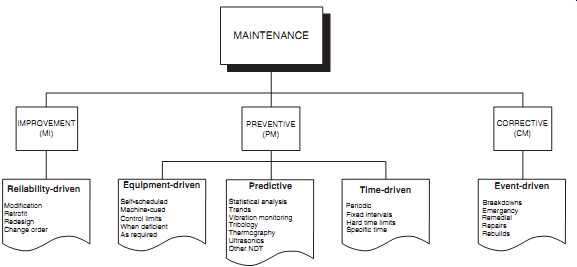

There are three main types of maintenance and three major divisions of preventive maintenance, as illustrated in FIG. 4.

Corrective Maintenance

The little finger in the analogy to a human hand used previously in the guide represents corrective (i.e., emergency, repair, remedial, unscheduled) maintenance. At present, most maintenance is corrective. Repairs will always be needed. Better improvement maintenance and preventive maintenance, however, can reduce the need for emergency corrections. A shaft that is obviously broken into pieces is relatively easy to maintain because little human decision is involved. Troubleshooting and diagnostic fault detection and isolation are major time consumers in maintenance. When the problem is obvious, it can usually be corrected easily. Intermittent failures and hidden defects are more time-consuming, but with diagnostics, the causes can be isolated and corrected. From a preventive maintenance perspective, the problems and causes that result in failures provide the targets for elimination by viable preventive maintenance. The challenge is to detect incipient problems before they lead to total failures and to correct the defects at the lowest possible cost. That leads us to the middle three fingers-the branches of preventive maintenance.

===

FIG. 4 Structure of maintenance.

MAINTENANCE: Reliability-driven Equipment-driven Predictive Time-driven Event-driven; Breakdowns Emergency Remedial Repairs Rebuilds Periodic Fixed intervals Hard time limits Specific time Statistical analysis Trends Vibration monitoring Tribology Thermography Ultrasonics Other NDT Self-scheduled Machine-cued Control limits When deficient As required Modification Retrofit Redesign Change order IMPROVEMENT (MI) PREVENTIVE (PM) CORRECTIVE (CM)

===

Preventive Maintenance

As the name implies, preventive maintenance tasks are intended to prevent unscheduled downtime and premature equipment damage that would result in corrective or repair activities. This maintenance management approach predominantly consists of a time-driven schedule or recurring tasks, such as lubrication and adjustments, which are designed to maintain acceptable levels of reliability and availability.

Reactive:

Reactive maintenance is done when equipment needs it. Inspection using human senses or instrumentation is necessary, with thresholds established to indicate when potential problems start. Human decisions are required to establish those standards in advance so that inspection or automatic detection can determine when the threshold limit has been exceeded. Obviously, a relatively slow deterioration before failure is detectable by condition monitoring, whereas rapid, catastrophic modes of failure may not be detected. Great advances in electronics and sensor technology are being made.

Also needed is a change in the human thought process. Inspection and monitoring should disassemble equipment only when a problem is detected. The following are general rules for on-condition maintenance:

• Inspect critical components.

• Regard safety as paramount.

• Repair defects.

• If it works, don't fix it.

Condition Monitoring:

Statistics and probability theory are the basis for condition-monitoring maintenance.

Trend detection through data analysis often rewards the analyst with insight into the causes of failure and preventive actions that will help avoid future failures. For example, stadium lights burn out within a narrow time range. If 10 percent of the lights have burned out, it may be accurately assumed that the rest will fail soon and should, most effectively, be replaced as a group rather than individually.

Scheduled:

Scheduled, fixed-interval preventive maintenance tasks should generally be used only if there is opportunity for reducing failures that cannot be detected in advance, or if dictated by production requirements. The distinction should be drawn between fixed interval maintenance and fixed-interval inspection that may detect a threshold condition and initiate condition-monitoring tasks. Examples of fixed-interval tasks include 3,000-mile oil changes and 48,000-mile spark plug changes on a car, whether it needs the changes or not. This approach may be wasteful because all equipment and their operating environments are not alike. What is right for one situation may not be right for another.

The five-finger approach to maintenance emphasizes eliminating and reducing maintenance need wherever possible, inspecting and detecting pending failures before they happen, repairing defects, monitoring performance conditions and failure causes, and accessing equipment on a fixed-interval basis only if no better means exist.

Maintenance Improvement

Picture these divisions as the five fingers on your hand. Maintenance improvement efforts to reduce or eliminate the need for maintenance are like the thumb, the first and most valuable digit. We’re often so involved in maintaining that we forget to plan and eliminate the need at its source. Reliability engineering efforts should emphasize elimination of failures that require maintenance. This is an opportunity to pre-act instead of react.

For example, many equipment failures occur at inboard bearings that are located in dark, dirty, inaccessible locations. The oiler does not lubricate inaccessible bearings as often as he or she lubricates those that are easy to reach. This is a natural tendency.

One can consider reducing the need for lubrication by using permanently lubricated, long-life bearings. If that is not practical, at least an automatic oiler could be installed.

A major selling point of new automobiles is the elimination of ignition points that require replacement and adjustment, the introduction of self-adjusting brake shoes and clutches, and the extension of oil-change intervals.

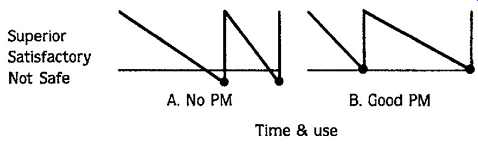

FIG. 5 Preventive maintenance to keep acceptable performance.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Overall, preventive maintenance has many advantages. It’s beneficial, however, to overview the advantages and disadvantages so that the positive may be improved and the negative reduced. Note that in most cases the advantages and disadvantages vary with the type of preventive maintenance tasks and techniques used. Use of on condition or condition-monitoring techniques is usually better than fixed intervals.

Advantages:

There are distinct advantages to preventive maintenance management. The primary advantages include management control, reduced overtime, smaller parts inventories, less standby equipment, better safety controls, improved quality, enhanced support to users, and better cost-benefit ratio.

Management Control. Unlike repair maintenance, which must react to failures, preventive maintenance can be planned. This means pre-active instead of reactive management. Workloads may be scheduled so that equipment is available for preventive activities at reasonable times.

Overtime. Overtime can be reduced or eliminated. Surprises are reduced. Work can be performed when convenient. Proper distribution of time-driven preventive maintenance tasks is required, however, to ensure that all work is completed quickly without excessive overtime.

Parts Inventories. Because the preventive maintenance approach permits planning, of which parts are going to be required and when, those material requirements may be anticipated to be sure they are on hand for the event. A smaller stock of parts is required in organizations that emphasize preventive tasks compared to the stocks necessary to cover breakdowns that would occur when preventive maintenance is not emphasized.

Standby Equipment. With high demand for production and low equipment avail ability, standby equipment is often required in case of breakdowns. Some backup may still be required with preventive maintenance, but the need and investment will certainly be reduced.

Safety and Pollution. If there are no preventive inspections or built-in detection devices, equipment can deteriorate to a point where it’s unsafe or may spew forth pollutants. Performance will generally follow a sawtooth pattern, as shown in FIG. 5, which does well after maintenance and then degrades until the failure is noticed and brought back up to a high level. A good detection system catches degrading performance before it ever reaches this level.

Quality. For the same general reasons discussed previously, good preventive maintenance helps ensure quality output. Tolerances are maintained within control limits.

Productivity is improved, and the investment in preventive maintenance pays off with increased revenues.

Support to Users. If properly publicized, preventive maintenance tasks help show equipment operators, production managers, and other equipment users that the maintenance function is striving to provide a high level of support. Note that an effective program must be published so that everyone involved understands the value of per formed tasks, the investment required, and individual roles in the system.

Cost-Benefit Ratio. Too often, organizations consider only costs without recognizing the benefit and profits that are the real goal. Preventive maintenance allows a three way balance between corrective maintenance, preventive maintenance, and production revenues.

Disadvantages:

Despite all the good reasons for doing preventive maintenance, several potential problems must be recognized and minimized.

Potential Damage. Every time a person touches a piece of equipment, damage can occur through neglect, ignorance, abuse, or incorrect procedures. Unfortunately, low-reliability people service much high-reliability equipment. The Challenger space shuttle failure, the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant disaster, and many less publicized accidents have been affected by inept preventive maintenance. Most of us have experienced car or home appliance problems that were caused by something that was done or not done at a previous service call. This situation results in the slogan:

"If it works, don't fix it."

Infant Mortality. New parts and consumables have a higher probability of being defective, or failing, than the materials that are already in use. Replacement parts are too often not subjected to the same quality assurance and reliability tests as parts that are put into new equipment.

Parts Use. Replacing parts at preplanned preventive maintenance intervals, rather than waiting until a failure occurs, will obviously terminate that part's useful life before failure and therefore require more parts. This is part of the trade-off between parts, labor, and downtime, of which the cost of parts will usually be the smallest component. It must, however, be controlled.

Initial Costs. Given the time-value of money and inflation that causes a dollar spent today to be worth more than a dollar spent or received tomorrow, it should be recognized that the investment in preventive maintenance is made earlier than when those costs would be incurred if equipment were run until failure. Even though the cost will be incurred earlier, and may even be larger than corrective maintenance costs would be, the benefits in terms of equipment availability should be substantially greater from doing preventive tasks.

Access to Equipment. One of the major challenges when production is at a high rate is for maintenance to gain access to equipment in order to perform preventive maintenance tasks. This access will be required more frequently than it’s with breakdown driven maintenance. A good program requires the support of production, with immediate notification of any potential problems and a willingness to coordinate equipment availability for inspections and necessary tasks.

The reasons for and against doing preventive maintenance are summarized in the following list. The disadvantages are most pronounced with fixed-interval maintenance tasks. Reactive and condition-monitoring tasks both emphasize the positive and reduce the negatives.

Advantages:

- • Can be performed when convenient

- • Increases equipment uptime

- • Generates maximum production revenue

- • Standardizes procedures, times, and costs

- • Minimizes parts inventory

- • Cuts overtime

- • Balances workload

- • Reduces need for standby equipment

- • Improves safety and pollution control

- • Facilitates packaging tasks and contracts

- • Schedules resources on hand

- • Stimulates pre-action instead of reaction

- • Indicates support to user

- • Ensures consistent quality

- • Promotes cost-benefit optimization

Disadvantages:

- • Exposes equipment to possible damage

- • Makes failures in new parts more likely

- • Uses more parts

- • Increases initial costs

- • Requires more frequent access to equipment

SUPERVISION

Supervision is the first, essential level of management in any organization. The super visor's role is to encourage members of a work unit to contribute positively toward accomplishing the organization's goals and objectives. If you have ever attempted to introduce change or continuous improvement in your plant without the universal support of your first-line supervisors, you should understand the critical nature of this function. As the most visible level of management in any plant, front-line supervisors play a pivotal role in both existing plant performance and any attempt at change.

Although the definition is simple, the job of supervision is complex. The supervisor must learn to make good decisions, communicate well with people, make proper work assignments, delegate, plan, train people, motivate people, appraise performance, and deal with various specialists in other departments. The varied work of the supervisor is extremely difficult to master. Yet, mastery of supervision skills is vital to plant success.

Most new supervisors are promoted from the ranks. They are the best mechanicals, operators, or engineers within the organization. Employees with good technical skills and good work records are normally selected by management for supervisory positions; however, good technical skills and a good work record don’t necessarily make a person a good supervisor. In fact, sometimes these attributes can act adversely to productive supervisory practices. Other skills are also required to be an effective supervisor. The complex work of supervision is often categorized into four areas, called the functions of management or the functions of supervision. These functions are planning, staffing, leading, and controlling.

Functions of Supervision

Planning involves determining the most effective means of achieving the work of the unit. Generally, planning includes three steps:

1. Determining the present situation. Assess such things as the present conditions of the equipment, the attitude of employees, and the availability of materials.

2. Determining the objectives. Higher levels of management usually establish the objectives for a work unit. Thus, this step is normally done for the supervisor.

3. Determining the most effective way of attaining the objectives. Given the present situation, what actions are necessary to reach the objectives?

Everyone follows these three steps in making personal plans; however, the supervisor makes plans not for a single person, but for a group of people. This complicates the process.

Organizing involves distributing the work among the employees in the work group and arranging the work so that it flows smoothly. The supervisor carries out the work of organizing through the general structure established by higher levels of management. Thus, the supervisor functions within the general structure and is usually given specific work assignments from higher levels of management. The supervisor then sees that the specific work assignments are completed.

Staffing is concerned with obtaining and developing good people. Because supervisors accomplish their work through others, staffing is an extremely important function. Unfortunately, first-line supervisors are usually not directly involved in hiring or selecting work group members. Normally, higher levels of management make these decisions; however, this does not remove the supervisor's responsibility to develop an effective workforce. Supervisor's are, and should be, the primary source of skills training in any organization. Because they are in proximity with their work group members, they are the logical source of on-the-job training and enforcement of universal adherence to best practices.

Leading involves directing and channeling employee behavior toward accomplishing work objectives. Because most supervisors are the best maintenance technicians or operators, the normal tendency is to lead by doing rather than by leading. As a result, the supervisor spends more time performing actual work assigned to the work group than he or she does in management activities. This approach is counterproductive in that it prevents the supervisor from accomplishing his or her primary duties. In addition, it prevents workforce development. As long as the supervisor performs the critical tasks assigned to the work group, none of its members will develop the skills required to perform these recurring tasks.

Controlling determines how well the work is being done compared with what was planned. This involves measuring actual performance against planned performance and taking any necessary corrective actions.

An effective supervisor will spend most of each workday in the last two categories.

The supervisor must perform all of the functions to be effective, but most of his or her time must be spent on the plant floor directly leading and controlling the work force. Unfortunately, this is not the case in many plants. Instead, the supervisor spends most of a typical workday generating reports, sitting in endless meetings, and per forming a variety of other management tasks that prevent direct supervision of the workforce.

The supervisor's work can also be examined in terms of the types of skills required to be effective:

Technical skills refer to knowledge about such things as machines, processes, and methods of production or maintenance. Until recently, all supervisors were required to have a practical knowledge of each task that his or her work group was expected to perform as part of its normal day-to-day responsibility. Today, many supervisors lack this fundamental requirement.

Human relations skills refer to knowledge about human behavior and to the ability to work well with people. Few of today's supervisors have these basic skills. Although most will make a concerted attempt to learn the basic people skills that are essential to effective supervision, few are given the time to change. The company simply assigns them to supervisory roles and provides them with no training or direction in this technical area.

Administrative skills refer to knowledge about the organization and how it works-the planning, organizing, and controlling functions of supervision.

Again, few companies recognize the importance of these skills and don’t provide formal training for newly appointed supervisors.

Decision-making and problem-solving skills refer to the ability to analyze information and objectively reach logical decisions.

In most organizations, supervisors need a higher level of technical, human relations, and decision-making skills than of administrative skills. As first-line supervisors, these skills are essential for effective management.

Characteristics of Effective Supervision

Supervisors are successful for many reasons; however, five characteristics are critical to supervisory success:

• Ability and willingness to delegate. Most supervisors are promoted from operative jobs and have been accustomed to doing the work themselves. An often difficult, and yet essential, skill that such supervisors must develop is the ability or willingness to delegate work to others.

• Proper use of authority. Some supervisors let their newly acquired authority go to their heads. It’s sometimes difficult to remember that the use of authority alone does not garner the support and cooperation of employees.

Learning when not to use authority is often as important as learning when to use it.

• Setting a good example. Supervisors must always remember that the work group looks to them to set the example. Employees expect fair and equitable treatment from their supervisors. Too many supervisors play favorites and treat employees inconsistently. Government legislation has attempted to reduce this practice in some areas, but the problem is still common.

• Recognizing the change in role. People who have been promoted into super vision must recognize that their role has changed and that they are no longer one of the gang. They must remember that being a supervisor may require unpopular decisions. Supervisors are the connecting link between the other levels of management and the operative employees and must learn to represent both groups.

• Desire for the job. Many people who have no desire to be supervisors are promoted into supervision merely because of their technical skills. Regard less of one's technical skills, the desire to be a supervisor is necessary for success. That desire encourages a person to develop the other types of skills necessary in supervision-human relations, administrative, and decision making skills.

Working without Supervision

There is a growing trend in U.S. industry to eliminate the supervisor function. Instead, more plants are replacing this function with self-directed teams, using a production supervisor to oversee maintenance, or using hourly workers to direct the work function. Each of these methods can provide some level of work direction, but all eliminate many of the critical functions that should be provided by the first-line supervisor.

Self-Directed Teams:

This approach is an adaptation of the Japanese approach to management. The functional responsibilities of day-to-day plant operation are delegated to individual groups of employees. Each team is then required to develop the methods, performance criteria, and execution of their assigned tasks. The team decides how the work is to be accomplished, who will perform required tasks, and the sequence of execution. All decisions require a consensus of the team members.

In some environments, this approach can be successful; however, the absence of a clearly defined leader, mentor, and enforcer can severely limit the team's effectiveness. By nature, any process that requires majority approval of actions taken is slow and inefficient. This is especially true of the self-directed work team. Composition of the work team is also critical to success. Typically, one of three scenarios takes place.

Some teams have a single, strong individual who in effect makes all team decisions.

This individual controls the decision process and the team always adopts his or her ideas. The second scenario is a team with two or more natural leaders. In this team composition, the strong members must agree on direction before any consensus can be reached. In many cases, the team is forced into inaction simply because disagreement exists among the strongest team members. The third team composition is one without any strong-willed members. Generally, this type of group founders and little, if any, productive work is provided. Regardless of the team composition, this attempt to replace first-line supervisors severely limits plant performance.

Cross-Functional Supervision:

A common approach to the reduction in first-line supervisors is to use production supervisors to oversee maintenance personnel. This is especially true on back-turns (i.e., second and third shifts). In most plants, maintenance personnel are assigned to these shifts simply as insurance in case something breaks down. Because of this under stood mission, these work periods tend to yield low productivity from the assigned maintenance personnel. Therefore, first-line supervision that can ensure maximum productivity from these resources is essential. The companies who recognize this fact are attempting to resolve the need for direct supervision and still reduce what is viewed as nonrevenue overhead (supervisors) by assigning a production supervisor to oversee back-turn maintenance personnel.

One of the fundamental requirements of an effective supervisor is his or her knowledge of the work to be performed. In most cases, production supervisors have little, if any, knowledge or understanding of maintenance. Moreover, they have little interest or desire to ensure that critical plant systems are properly maintained. The normal result of this type of supervision is that nothing, with the possible exception of emergencies, is accomplished during these extended work periods. The maintenance personnel assigned to the back-turns simply sit in the break room waiting for some thing to malfunction.

Hourly Workers as Team Leaders:

With few exceptions, this is the most untenable approach to supervisor-less operation.

In this scenario, hourly workers are assigned the responsibility of first-line supervision. This responsibility is typically in addition to their normal work assignments as an operator or maintenance craftsperson. I cannot think of any position in corporate America that is more unfair or has the least chance of success.

If you were in the military, this position is similar to a Warrant Officer in the Army.

Real officers look down on them, but expect them to produce results; noncommissioned officers view them with total disdain; and soldiers treat them with less respect than officers from higher ranks. They simply cannot win.

It’s the same with the team leader concept. Senior management expects the team leader to provide effective leadership, enforce discipline, and perform all of the other duties normally assigned to a first-line supervisor; hourly workers tend to either treat the team leader as "one of them" or totally ignore their direction. The team leader is truly a pariah; he or she does not belong to the management team or the hourly work force. They are caught in purgatory, disliked by both management and their peers.

The common problem with these attempts to replace first-line supervision is the lack of training and infrastructure support that is essential to effective performance. As is the case in most functions within a plant or corporation, employees are simply not provided with the skills essential to the successful completion of assigned tasks.

Combine this with corporate policies and procedures that don’t provide clear, universal direction for the day-to-day operation of the plant, and the potential for success is nil.

STANDARD PROCEDURES

First, we should define the term standard procedure. The concept of using standards is predicated on the assumption that there is only one method for performing a specific task or work function that will yield the best results. It also assumes that a valid procedure will permit anyone with the necessary skills to correctly perform the duty or task covered by the procedure.

In the case of operations or production, there is only one correct way to operate a machine or production system. This standard operating method will yield the maximum, first-time-through prime capacity at the lowest costs. It will also ensure optimum life-cycle costs for the production system. In maintenance, there is only one correct way to lubricate, inspect, or repair a particular machine. Standard maintenance procedures are designed to provide step-by-step instructions that will ensure proper performance of the task as well as maximum reliability and life-cycle cost from the machine or system that is being repaired.

This same logic holds true for every task or duty that must be performed as part of the normal activities that constitute a business. Whether the task is to develop a business plan; hire new employees; purchase Maintenance, Repair, and Operations (MRO) spares; or any of the myriad of other tasks that make up a typical day in the life of a plant, standard procedures ensure the effectiveness of these duties.

Reasons for Not Using Standard Procedures

There are many reasons that standard procedures are not universally followed. Based on our experience, the predominant reason is that few plants have valid procedures.

This is a two-part failure. In some plants, procedures simply don’t exist. For what ever the reason, the plant has never developed procedures that are designed to govern the performance of duties by any of the functional groups within the plant. Each group or individual is free to use the methods that he or she feels most comfortable with. As a result, everyone chooses a different method for executing assigned tasks.

The second factor that contributes to this problem is the failure to update procedures to reflect changes in the operation of the business. For example, production procedures must be updated to correct for changes in products, production rates, and a multitude of other factors that directly affect the mode of operation. The same is true in maintenance. Procedures must be upgraded to correct for machine or system modifications, new operating methods, and other factors that directly affect maintenance requirements and methods.

The second major reason for not using standard procedures is the perception that "all employees know how to do their job." Over the years, hundreds of maintenance man agers have reported that standard maintenance procedures are unnecessary because the maintenance craftspeople have been here for 30 years and know how to repair, lubricate, and so on. Even if this were true, maintenance craftspeople who have been in the plant for 30 years will retire soon. Will the new 18-year-old replacement know how to do the job properly?

Creating Standard Procedures:

Creating valid standard procedures is not complicated, but it can be time and labor intensive. When you consider every recurring task that must be performed by all functional groups within a typical plant, the magnitude of the effort required to create standards may seem overwhelming; however, the long-term benefits more than justify the effort. Where do you start? The first step in the process must be a complete duty-task analysis. This evaluation identifies and clarifies each of the recurring tasks or duties that must be performed within a specific function area, such as production or maintenance, of the plant. When complete, the results of the duty-task analysis will define task definition, frequency, and skill requirements for each of these recurring tasks.

With the data provided by the duty-task analysis, the next step is to develop best practices or standard procedures for each task. For operating and maintenance procedures, the primary reference source for this step are the operating and maintenance manuals that come with the machine or production system. These documents define the vendors' recommendations for optimum operating and maintenance methods. The second source of information is the actual design of the involved systems. Using best engineering practices as the evaluation tool, the design will define the operating envelope of each system and system component. This knowledge, combined with the vendors' manuals, provides all of the information required to develop valid standard operating and maintenance procedures.

The content of each procedure must be complete. Assume that the person (or persons) who will perform the procedure is doing it for the first time. Therefore, the procedure must include enough definition to ensure complete compliance with best practices.

Because each procedure requires specific skills for proper performance, the procedure must also define the minimum skills required.

The level of detail required for a viable standard procedure will vary with the task's complexity. For example, an inspection procedure will require much less detail than one for the complete rebuild of a complex production system; however, both must have specific, clearly defined methods. In the case of an inspection, the procedure must include specific, quantifiable methods for completion. A procedure that says "inspect V-belt for proper tension" is not acceptable. Instead, the procedure should state exactly how to make the inspection as well as the acceptable range of tension.

For a major repair, the procedures should include drawings, tools, safety concerns, and a step-by-step disassembly and reassembly procedure.

Standard Procedures Are Not Enough

Without universal adherence, standard procedures are of no value. If adherence is left to the individual operators and maintenance craftspeople, the probability of measurable benefit is low. To achieve benefit, every employee must constantly and consistently follow these procedures. The final failure of most corporations is a failure to enforce adherence to established policies and procedures. It seems to be easier to simply let everyone do his or her own thing and hope that most will choose to follow established guidelines. Unfortunately, this simply won’t happen. The resultant impact on plant performance is dramatic, but few corporate or plant managers are willing to risk the disfavor of their employees by enforcing compliance.

From my viewpoint, this approach is unacceptable. The negative impact on performance created by a failure to universally follow valid procedures is so great that there can be no justification for permitting it to continue. The simple act of implementing and following standard procedures can eliminate as much as 90 percent of the reliability, capacity, and quality problems that exist in most plants. Why then, do we continue to ignore this basic premise of good business practices?

WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT

When one thinks logically about the problems that limit plant and corporate performance, few could argue that improving the skills of the workforce must rank very high. Yet, few corporations address this critical issue. In most corporations, training is limited to mandated courses, such as safety and drug usage. Little, if any, of the annual budget is allocated for workforce skills training. This failure is hard to under stand. It should be obvious that there is a critical need for skills improvement through out most organizations. This fact is supported by three major factors: (1) lack of basic skills, (2) workforce maturity, and (3) unskilled workforce pool.

Lack of Basic Skills

Evaluations of plant organization universally identify a lack of basic skills as a major contributor to poor performance. This problem is not limited to the direct workforce but includes all levels of management as well. Few employees have the minimum skills required to effectively perform their assigned job functions.

Workforce Maturity

Most companies will face a serious problem within the next 5 to 10 years. Evaluations of the workforce maturity indicate that most employees will reach mandatory retirement age within this period. Therefore, these companies will be forced to replace experienced employees with new workers who lack basic skills and experience in the job functions needed.

Unskilled Workforce Pool

The decline in the fundamental education afforded by our education system further compounds the problem that most companies face in the workforce replacement process. Too many potential new employees lack the basic skills sets, such as reading, writing, mathematics, and so on that are fundamental requirements for all employees.

This problem is not limited to primary education. Many college graduates lack a minimum level of the basic skills or practical knowledge in their field of specialty (e.g., business, engineering). If you accept these problems as facts, why not train? One of the more common reasons is a lack of funds. Many corporations face serious cash-flow problems and low profitability. As a result, they believe that training is a luxury they simply cannot afford.

Although this might sound like a logical argument, it simply is not true. Training does not require a financial investment. External funds are available from other sources that can be used to improve workforce skills. Leading the list of providers of training funds are the federal, state, and local governments. Although these funds are primarily limited to the direct workforce, grants are also available for all levels of management.

In fact, government-sponsored agencies are available that will help small and medium sized companies develop and grow.

Manufacturing Extension Partnership

The Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP) is a nationwide network of not for-profit centers in more than 400 locations nationwide, whose sole purpose is to provide small and medium-sized manufacturers with the help they need to succeed.

The centers, serving all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, are linked through the Department of Commerce's National Institute of Standards and Technology. That makes it possible for even the smallest firm to tap into the expertise of knowledgeable manufacturing and business specialists all over the United States.

To date, MEP has assisted more than 62,000 firms.

Each center has the ability to assess where your company stands today, to provide technical and business solutions, to help you create successful partnerships, and to help you keep learning through seminars and training programs. The special combination of each center's local expertise and their access to national resources really makes a difference in the work that can be done for your company (www.mep.nist.gov). The primary focus of training grants is through the U.S. Department of Labor. The Job Training Partnership Act and several other federal initiatives, such as the Employment and Training Administration (ETA), have been established with the sole mission of resolving the workforce skills problem that is a universal problem in U.S. industry.

U.S. Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration

The ETA's mission is to contribute to the more efficient and effective functioning of the U.S. labor market by providing high-quality job training, employment, labor market information, and income maintenance services primarily through state and local workforce development systems. The ETA seeks to ensure that American workers, employers, students, and those seeking work can obtain information, employment services, and training by using federal dollars and authority to actively support the development of strong local labor markets that provide such resources (www.doleta.gov).

Apprenticeship Programs

Within the framework of the ETA, the U.S. Department of Labor provides apprenticeship training. The purpose of these programs, authorized by The National Apprenticeship Act of 1937, is to stimulate and assist industry in developing and improving apprenticeships and other training programs designed to provide the skills workers need to compete in a global economy. On-the-job training and related classroom instruction in which workers learn the practical and theoretical aspects of a highly skilled occupation are provided. Joint employer and labor groups, individual employers, and/or employer associations sponsor apprenticeship programs.

The Bureau of Apprenticeship and Training (BAT) registers apprenticeship programs and apprentices in 23 states and assists or oversees Apprenticeship Councils (SACs), which perform these functions in 27 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. The government's role is to safeguard the welfare of the apprentices, ensure the quality and equality of access, and provide integrated employment and training information to sponsors and the local employment and training community.

Job Training Partnership Act:

The Job Training Partnership Act (JTPA) provides job-training services for economically disadvantaged adults and youth, dislocated workers, and others who face significant employment barriers. The act, which became effective on October 1, 1983, seeks to move jobless individuals into permanent self-sustaining employment. State and local governments, together with the private sector, have primary responsibility for development, management, and administration of training programs under JTPA (www.doleta.gov/programs/factsht/jtpa.htm).

Economic Dislocation and Worker Adjustment Assistance Act (EDWAA):

This act, as part of the JTPA, provides funds to states and local grantees so they can help dislocated workers find and qualify for new jobs. It’s part of a comprehensive approach to aid workers who have lost their jobs that also includes provisions for retraining displaced workers. Workers can receive classroom, occupational skills, and/or on-the-job training to qualify for jobs that are in demand. Basic and remedial education, entrepreneurial training, and instruction in literacy or English-as-a-second language (ESL) training may be provided.

Training Grants

Training grants are distributed though state and local agencies. The following list provides the initial contact point for information and applications for these funds. Note that all states don’t currently participate in these federally funded programs, but most provide funds and/or other assistance for employee skills training.

Most labor agreements include a stipulation that a percentage of union dues will be set aside for employee (membership) training. In some cases, the available funds are substantial and often go unused. Although these funds are exclusively limited to the hourly workforce, they represent a real source of funding that can be effectively used to improve plant performance.

A lack of money is not the reason that corporations fail to provide the training that is sorely needed to improve workforce performance. Millions of dollars are available to fund these training programs. The sad part is that much of this available funding is not used. Corporations, for whatever reasons, fail to recognize the seriousness of this problem or to do anything about it.

America's Job Bank:

Employees who become displaced because of layoffs, plant closures, or who simply want to seek a more rewarding position have a free resource that is also provided by the government. America's Job Bank is a partnership between the U.S. Department of Labor and the public Employment Service. The latter is a state-operated program that provides labor exchange service to employers and job seekers through a network of 1,800 offices throughout the United States.

Since 1979, the states have cooperated to exchange information that offers employers national exposure of their job openings. In the spring of 1998, the additional service of posting résumés from job seekers was initiated. Publicizing job listings on a national basis has helped employers recruit the employees needed to help their business succeed, while providing the American labor force with an increased number of opportunities to find work and realize their career goals.

The America's Job Bank computerized network links state Employment Service offices to provide job seekers with the largest pool of active job opportunities avail able anywhere. It also offers nationwide exposure for job seekers' résumés. Most of the jobs listed on the America's Job Bank are full-time listings and most are in the private sector. The job openings come from all over the country and represent all types of work, from professional and technical to blue collar, from management to clerical and sales. Perhaps the best feature of the America's Job Bank is that it's free. There is no charge to either the employer who lists jobs or to job seekers who use the Job Bank to obtain employment. These services are funded through the Unemployment Insurance taxes paid by employers.

Prev. | (You're on the final page of this guide. Click here to return to INDEX)