Low-Maintenance Landscape: Flowers and Vegetables

|

Garden catalogs, artfully designed to get you to buy lots of seeds, tempt you with big, splashy pictures of gorgeous flowers and delicious vegetables. I should know; I’ve succumbed to their allure many times myself. But despite the glory those full-color photos promise, not all of the seeds you buy and plant will reward you with such specimens, unless perhaps you’re willing to devote the kind of time and attention that professional gardeners can to get such results. On the other hand, there are certain flowers and vegetables that demand very little, and give much in return. Flowers That Give You More Hammock Time Popular fashions in flowers reveal the same human foibles as fashions in flowering shrubs and other ornamental plants. Those that best with stand nature’s hazards endure to become common. Becoming common, they become uninteresting to the homeowner’s bent for “something different.” When “something different” requires hard work and attention to keep it alive, the old reliables are rediscovered and become popular until another generation forgets. Then the pendulum swings again. Perennials Perennials—flowers that once planted, come up and bloom year after year—are the first choice for low maintenance. But selection should be done carefully. Some perennials are more perennial than others; that is, some will last for many years without care, while others need to be dug up and the roots divided regularly. Some have special problems with insects or diseases that require regular maintenance. And the classic perennial border, popular in Victorian times and now enjoying a rebirth, is a high- maintenance project that should be undertaken only by those for whom flower growing is a major hobby. In a perennial border, plants are arranged artfully from low-growing varieties in front to tall ones in the rear, and chosen so that something is coming into bloom from spring to fall. One is constantly weeding, cutting off old blossoms, tying up, setting out, and taking in. But some perennials, handled in less demanding ways, can give you flowers throughout your growing season with no work at all. For starters, here’s a list that has grown out of my experience. (Note that I mention botanical names only when I think it necessary to distinguish one specific genus or species or variety from another. If no botanical name appears, then you can assume that I’m referring to the flower that everybody—or most everybody—knows by its common name.) PEONIES This flower ranks number one with me. I’m sure there is something you should do to peonies in the way of care, but in all the years we’ve grown them, we did exactly nothing. Peonies make large gorgeous flowers in varying shades of red, pink, and white. They bloom for much of the spring. No insect harms them much. Don’t spray them as one gardener I know did. He got rid of the ants, sure enough, but the flower buds would not open. Why? The ants suck a nectar that otherwise seals in the bud. Without the ant performing this operation, the buds won’t open properly.

Treat a peony as an ornamental bush. The shoots in spring grow into a tight clump and are easy to mow around, making the bush a good choice for an isolated lawn location or as a row along a drive or walk. THE COMMON DAYLILY Hemerocallis fulva and H. fiava, especially the former, are the best varieties on my list. Many, many hybrids and varieties of daylily are available, all of them fairly low maintenance, but none beat these old originals in that respect. You find H. fulva growing along roadsides in tight clumps that defy weeds to come up among them. They endure mowings, herbicides, and farm equipment driving over them along our country roads and come back the next year as luxuriant as ever. Extremely hardy and pest-free, a bed of them in the yard or by the house requires no work and remains attractive even after blooming in summer. Daylilies are sup posed to be dug up every few years and the roots divided, but H. fulva will go on forever without this work. H. flava, the lemon daylily, is nearly as low care, the blossom smaller and yellow rather than orange. Tiger lilies look somewhat like old-fashioned daylilies but are spotted. Many, many new varieties are available from most garden catalogs. Colors range from red, pink, white, yellow, and cream to gold in addition to the old traditional orange. They are all hardy and enduring and good for low maintenance, although some do not grow in the tight clumps that so successfully keep out weeds.

LILY OF THE VALLEY

Especially for a shady spot by the house, a bed of these tiny lilies (Convallaria majalis or C. montana) will last forever with a little weeding. The roots spread out and send up new shoots until a solid bed is formed. The new shoots arise from pips, as they are called, on the roots, which can be rather easily removed to start new beds or to force for winter blooms indoors. The flowers are small but very fragrant. WINTER ACONITE This member of the buttercup family (Eranthis hyemalis) is especially desirable because it blooms extremely early in the year—as early as late February even in my cold climate of northern Ohio. It takes only the slightest thaw to awaken it, and once blooming, will withstand temperatures falling into the teens with ease. If biotechnology could transfer this kind of cold hardiness to vegetables, northerners would be eating sweet corn in April. The other advantage of these dainty yellow flowers is that you can plant them right in the lawn, and if you are just a bit patient with the lawn mower, they will mature before the real mowing season begins. You can throw right over them. Zero maintenance. And the seeds will spread the plant over the lawn very delightfully. The flowers even do very well in shady places (largely because they put on most of their yearly growth before leaves appear elsewhere). There are other small early spring flowers that can be handled like winter aconite, although they need a bit more time to mature before they can be mowed off without weakening them for next year’s growth; snow drop (Galan thus spp.) and grape hyacinth (Muscari spp.) are two of these. ADAM’S NEEDLE This is a type of yucca (Yucca filanientosa) that is also called Spanish bayonet. It is hardy to zone 5 (see the zone map in section 8), and is an extremely low-care flower for dry, sandy, sunny areas. It will grow in good soil, too, have no fear, and come up year after year with a shower of white blooms in summer. It reaches a height of about 6 feet in zone 5 and will grow taller farther south. The sharp bayonet-like leaves make it somewhat undesirable in a child’s play area. By the same token, it is much less likely to be harmed by frisky cats and dogs than some other flowers are. DAFFODILS The daffodils (Narcissus sp.) I’m talking about are the ones naturalized in a woodland or meadow setting; they go on nearly forever. There is a solitary one in our woods, planted by who knows who, that blooms every spring and then spends the rest of the summer in deep shade, dreaming about its few brief days of glory. It is a low-care flower to grow along a fence. When summer comes and the weeds and grass want to take over, just mow. Next spring the daffodils will be back. So will crocuses planted with them. THE LITTLE SEMIWILD IRISES These flowers (Iris versicolor and I. cristata) are not as showy as their bigger cousins, but they get along on their own far better and do not need to be lifted and divided so often or protected from weeds, slugs, and iris borers as much. They adapt to almost any site except those that are very dry, and they are particularly good for a wet, marshy place. ASTERS For a late fall bloom, the hardy asters are the least bother. But they ought to be lifted and divided about every third year.

There are other good perennials, of course, but the ones we think of first usually have some maintenance chore that prevents them from being included in my list of easy-care favorites. Delphiniums should be staked; mums should be pinched back; daisies, sweet Williams, and hollyhocks are not long lasting without replanting; dahlias should be lifted every fall. Daisies will often replant themselves and so will hollyhocks, but as such they probably should be dealt with more accurately as annuals. WILDFLOWERS

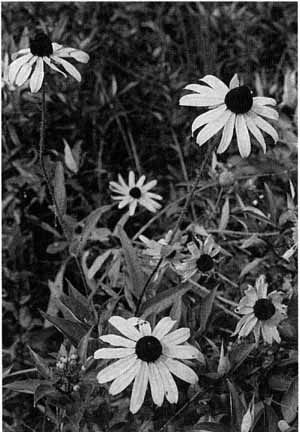

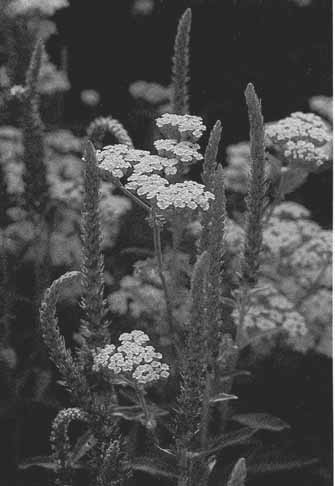

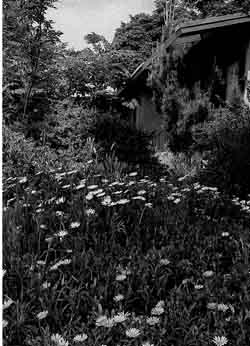

The group of perennials requiring the least work of all are what we commonly call wildflowers. The trick to growing them with low maintenance is to grow them in the same kind of habitat they are accustomed to. In most cases, this means a woodsy or meadow environment, not in cultivated rows, borders, or beds. Thus bloodroot, dogtooth violet, Dutch man’s-breeches, trillium, Virginia bluebell, wild geranium, wild phlox, and wood anemone like a woodland environment, or more accurately, open glades in a woods. Black-eyed Susan, blue-eyed grass, columbine, evening primrose, poppy, spring beauty, and yarrow, to name a few, grow from the edge of the woods out into sunny fields. Some need very specific soil requirements: it is almost always useless to try to grow wild lady’s slippers outside their natural range. Digging them up should be a crime and in some places is. Meadow wildflowers endure in lawns if mowing is curtailed until the particular plant has matured, as I mentioned in section 7. In a typical yard, the woodsy wildflowers will not compete well with grass and need a place more or less to themselves near or under trees, where a moist leaf mold soil can be maintained. My backyard is a compromise between grass and flowers, made possible because it is too shady for vigorous grass growth, and because I let falling oak leaves lie (like sleeping dogs) much of the time. Thus I am able to let many wildflowers grow and bloom in spring. Columbine, dandelion, fire pink, Jacob’s ladder, shooting star, spring beauty, trillium, trout lily, violet, Virginia bluebell, wild geranium, wild phlox, winter aconite (not technically a wildflower), and wood anem one grow until about July 1, when I mow the area into a reasonably neat lawn for the rest of the year. Moneywort crawls low on the ground and blooms yellow most of the summer. I will let clumps of this or that grow; for instance, an occasional pokeberry or blue-eyed grass that strikes my fancy. My maintenance in all this is a vigilant eye and a quick hand on the mower’s steering mechanism, nothing more. Some of the wildflowers spread from roots, others reseed themselves, sometimes dying out in one area and appearing in another. The blazing red fire pinks move every year, and I must be alert to their dark green leaf clumps that grow in late summer or early spring and from which the June blooms will grow. With a wildflower lawn, never has laziness been so rewarded.

Annuals Can Be Carefree, Too The simple difference between an annual and a perennial (although often the difference isn’t that simple) is that the former needs to be planted or set out every year. This may seem like high maintenance compared to perennials, but that’s not necessarily the case. My mother had a saying about flowers that bears repeating: “When in doubt, plant zinnias.” She meant that no matter how ignorant or busy a person was, or how questionable the soil, zinnias would grow and bloom profusely. ZINNIAS Zinnia seeds will germinate faster than anything except maybe radishes. They will grow in most regions, ignored by pest insects and rabbits ornery enough to eat pansies right beside them. Mildew can be a problem, but because zinnias grow and bear in the dry, hottest part of the summer, this is rarely cause for concern. If you water them (usually not necessary but it makes certain insecure types of gardeners feel better), water only the soil, not the leaves. Zinnias make excellent cut flowers, and for that purpose are often grown in the garden in rows and weeded with the tiller as you would corn. They’re very easy to care for that way. They are available from most mail-order seed houses. MARIGOLDS Zinnias generally bloom all summer, and about the time they begin to fail, the low-maintenance flower gardener will have marigolds coming into bloom in full force until hard frost. Marigolds came originally from ancient Mexico and to this day remain fairly immune to the vicissitudes of dry weather. Bugs do not bother marigolds, which some believe have their own insect-repellent powers. They are often planted next to beans to keep bean beetles at bay. Those who say they have success with this practice use the old-fashioned marigolds with the pungent odor. Both these and the French marigolds will rid the soil of nematodes, as has been demonstrated by scientific experiment. Some gardeners say marigolds will discourage rabbits, too, but in my experience, a hungry rabbit can be discouraged only by a large dog, a fence, or a bullet.

Garden Food with Much Less Sweat In my many years of vegetable gardening, I’ve tried all kinds of weird vegetables, sometimes just out of curiosity, sometimes for the challenge of it, and sometimes just for the sake of trying something different. But I always go back to the tried and true, because they are so reliable and they are so undemanding. A Is for Asparagus The low-maintenance vegetable garden begins with asparagus. Like other low-maintenance perennials, an asparagus bed, once planted, will last 15 years and longer. Because asparagus is grown commercially in light or sandy soil (in New Jersey, Michigan, and California), many people believe it won’t grow in heavier soils, but nothing could be further from the truth. Asparagus grows well in any fertile, neutral soil, and when grown in clays and barns, it’s not sandy when you eat it. Sand is only advantageous if fertilized heavily because it usually guarantees a well-drained soil, which asparagus must have, and allows you to cultivate weeds over the bed without hurting the roots in early spring before the shoots begin to grow. Heavier soils don’t dry out soon enough to do that. Weeding is the only maintenance necessary on vigorously growing asparagus, and that need not take much time on a bed about 20 feet long and about 2 feet wide—plenty big for a family. The asparagus beetle is seldom very harmful after a bed is established. For the lowest maintenance, proceed in this manner: Plant seeds or roots—the latter means asparagus on the table a year sooner, but roots cost more. Dig a trench about 8 inches deep and 4 inches wide and plant the seed or roots in the bottom, covering the seed just barely, or covering the roots with about 2 inches of dirt. As the little plant grows, fill in with dirt gradually. This takes more or less all summer but the operation is at the same time also burying little weeds around the plants that would otherwise be competing with them. If you can mix in some compost with the dirt that you are filling in, all the better, of course. In the second year, a new and thicker plant will replace the spindly first year’s one, and if the soil is rich and the weather good, maybe two or three shoots will grow. Leave them. You want the plant to build up a big root system fast so that next year you can begin to harvest a few spears. If you planted roots, you might take a few spears in the second year, but I wouldn’t really advise it. In the third year, you can begin to harvest, but take only a few early shoots from each original plant and let the rest grow. By the fourth year, you can start picking in earnest, but the trick here is to leave one of the earliest shoots to grow at each original plant so that from the very beginning of the season, root invigoration is taking place. Then, quit harvesting a month after you begin so that more shoots can come up and grow all summer. By the fifth year, you should not have to worry about taking too many shoots except to quit harvesting about a month after you begin. In the sixth year and thereafter, you can continue picking a few late spears even later than that, because enough spears will have grown up and be past harvestable size by then to ensure a healthy crop the next year. The more top growth over your bed, the better insurance of a good crop the following year, and the shade of that growth helps keep weeds from growing underneath from July until frost. After frost, run your mower over the bed, grinding up the old residue into mulch. You can wait and do that in early spring instead if you wish. The worst weed in the asparagus bed is volunteer asparagus that grows from the seeds of your crop plants. If allowed to grow, these seedlings overcrowd the bed and give you a bunch of pencil-thin shoots, not the thick succulent ones you want. Therefore, the real Cadillac of asparagus beds is composed of only male plants. Both male and female plants bloom, but only the female bears seed inside red berries. As far as I know, you can’t buy just male roots, and knowledgeable gardeners eventually start a permanent bed with roots from a mixed row, taking the male plants for transplanting. Planting roots or seeds in the trench is done mostly because as the years pass, the root crowns gradually rise higher in the soil until they eventually emerge. The plants then need to be lifted and reset. It also appears that the more shallow the crowns are, the more spindly the shoots. Mulching yearly tends to raise the bed a little as the crowns rise and so adds years of good production to a bed. Mulching with manure and compost also gives the asparagus the nutrients it needs for good growth. As the mulch rots, it does something else for low maintenance that more than repays the time applying it: The soil becomes so soft and loose that you can work it with your fingers. Once the shoots start springing up, I have found no other way to weed the asparagus bed properly than with my fingers, working gently around the stalks to loosen and bury small weeds as they come up. One weeding like this in May and another in June, and you are finished for the year. The shade of the stalks, plus the addition of new mulch (which should only be applied after harvesting is completed, especially if you use chicken manure like I do), controls weeds the rest of the year. In harvesting spears, it is better to break them off than cut them with a knife below soil level as some books mistakenly instruct. Break the spear where it wants to break easily, and you will be certain that the spear you take to the house is all tender. If you cut low, a portion at the lower end may be too tough. Experience soon teaches you the gentle art of breaking. Also, the biggest, fattest stalks are generally the tenderest if harvested at the proper time. Friends of ours confessed that when they first prepared a batch of our asparagus, they trimmed off the butt ends. When they tasted how good and tender the fat stalks were, they retrieved the trimmings and cooked them, too! Rhubarb Never Fails Rhubarb is good for low-maintenance gardeners because it is so forgiving; it never demands to be harvested. In fact, you can grow a plant or two as a sort of ornamental, right out on the lawn if you wish, and never harvest it. It’s easy to mow or cultivate around, too. Those huge leaves keep weeds from growing up through the plant, and if you mow and till off some of the lower leaves, no real harm is done. Rhubarb is indestructible throughout the Midwest and I assume else where. Ultra-hardy, adaptable to any reasonably well-drained soil, and impervious to most insect attacks (the leaves are slightly toxic with oxalic acid), you simply stick a root in the ground and fertilize it a little until it gets established. You can buy seed; the Victoria variety is a good one, and Burpee is one source for it. Other varieties are MacDonald and Valentine. But you need not necessarily buy rhubarb seed; you should be able to get a start from a plant in your neighborhood. Most old plants need to be dug up and the roots divided anyway. Quite a bit of variety exists in the ubiquitous rhubarb plants of any neighborhood, and some are better than others, at least in terms of vigor. “Improved” varieties tend to have redder stalks, and although they do not necessarily taste any better than the greenish red stalks of other older strains, many gardeners find them more desirable. But in our garden, the reddest stalked plants are the least vigorous. Getting a start from an old plant in your neighborhood guarantees you a strain acclimated to your soil. Winter Onions Grow Like Weeds What we call winter onions are perennials that produce bulbs at the tops of the stalks and bulblets on the roots each year. You may know them as nest onions or as Egyptian tree onions. Whatever they are called, your greatest challenge in growing them is keeping them from taking over your landscape, and I speak only a little facetiously. I have never seen anything so tough. Mine grow even in partial shade, which they should not. I run the tiller down both sides of the row occasionally to kill the new plants that form when the bulblets on the stalk fall over to the ground. I’ve even mowed the plants off in midsummer to curtail their growth. And when the onions get too rambunctious, I run the tiller right over them. But nothing daunts them. Whoever first called them “multiplier onions” should get a Pulitzer prize for accurate reporting. I keep these weed onions, or they keep me, for a good reason: Not only are they low maintenance, but they can (in fact, must) be harvested in the very earliest spring or late winter when there is nothing else fresh from the garden. They begin to grow in the fall, and as soon as the snow recedes in February or March, they perk right up and start growing again. I have harvested them when snowdrifts were still melting 3 feet away. As soon as the weather warms enough to awaken other plants, these onions become too bitter, but how delicate they taste in February! You can pull up a cluster, gently separate the bulbs in the bunch, and then peel the skin away and the outer covering of stalk to reveal scallions of unexcelled delicacy.

These onions are similar, but not the same, as the evergreen long white bunching onions available from most catalogs. Bunching onions do not form bulbs and won’t survive hard winters, or if they do, will not survive forever the way winter or Egyptian tree onions will. Onion maggots do not bother Egyptian tree onions, nor does any other bug or disease that I know of. They are available from Thompson & Morgan, Inc., P.O. Box 100, Farmingdale, NJ 07727. Remember, these onions will not take the place of regular spring onions in May, but there is no other onion in the North for late winter and early spring eating. The Annual Vegetables with the Least Problems The hardest job you’ll probably have with the vegetables below is preparing the planting bed for them every year—an inevitable chore for anyone who grows annuals. SWEET POTATOES The sweet potato ranks at the top of this list in my northern garden and I’m sure it ranks high in the South, too. Centennial is the variety I like—the deep orange, moist-textured kind often referred to as yarns in the South. The white and the lighter yellow sweet potatoes are too mealy in texture to suit my taste. Buy plants and set them out after all danger of frost and chilly weather has passed. If the ground is dry; water the new plants once or twice. They take right off and vine so thickly that after a weeding or two, they will shade out most weeds in their territory. In 30 years I have never seen anything attack the plants. Sometimes mice or bugs eat at the tubers a little, but they never do any serious harm. Be sure to harvest before a heavy frost kills the vines, as the green vines wilting suddenly from frost can impart an off-taste to the potatoes. RADISHES Radishes are the other no-care vegetable in our garden. They grow so fast, pests are rarely serious problems. There are many kinds of radishes, including fall and winter ones. Weird kinds like Munchen Bier has podlike fruit aboveground that’s good for salads, and April Cross or Mooli from Japan is a white radish that won’t bolt so badly when hot weather comes. (Both these varieties are available from Thompson & Morgan mentioned above and listed in Appendix B.) Radishes are not a major part of anyone’s diet, but they are one of those foods that add some welcome variety to many fresh dishes. Of course, they make fine eating all by themselves, too. If you want to impress the veteran gardener next door, you can easily do it by planting some of the more unusual varieties—ones she’s probably never even heard of. And doing so won’t take any more time or effort than planting the common little red radish everybody else grows. ZUCCHINI Zucchini is, of course, on everyone’s low-maintenance list of vegetables. It is much easier to grow 1,000 zucchini than to grow 20, so plant only four seeds and stand back. Zucchini actually do have pest problems enough to stop less aggressive species—from striped cucumber beetle when young, to borers when old, but even so, you will get more squash than you bargained for. TOMATOES Where soil-borne wilts are not a problem, the tomato is a surprisingly carefree vegetable to grow, which is why everyone does grow it. The trick to growing tomatoes without working hard at it is to ignore all the stakes, wire cages, and various other trellis arrangements that fussy gardeners tell you are necessary for success. And ignore all that malarkey about pinching off suckers. These so-called suckers are fruit-producing stems, and they are pinched off only when you are training tomatoes to stakes and have to limit the number of fruit, or when you are trying to grow a bigger tomato than your neighbor. When your tomato plants have started growing well and are beginning to blossom, spread straw mulch around them and let the poor things grow like they want to, over the straw. The tomatoes will be clean, they will suffer less from blossom end rot because the mulch will keep the soil cool and moist, and even if you don’t get the biggest tomato on the block, you will get a whole lot more than your neighbors who boast about their fancy staking systems. LETTUCE Lettuce presents very few problems—none at all for me and my family. A bed of it, grown in a 5-by-5-foot cold frame, will provide, before it bolts, all a family needs. The only weed of note in our cold frame is sour grass, a type of oxalis that can be added in small amounts right to the salad with the lettuce. Its lemony flavor adds a nice touch. Rabbits are the worst pest in our garden, but contrary to tradition, they don’t eat lettuce. OTHER SALAD GREENS For another salad ingredient with no maintenance at all, plant a linden (basswood) tree. The young leaves are quite tasty in salads. And the flowers and young leaves of the common violet plant found in many lawns in spring are a delight in salads, too. And of course dandelions before they blossom are good wilted with vinegar and garnished with chopped boiled eggs and bacon bits. If you are drenching your landscape with toxic sprays, you’ll have to forgo such delights. CORN AND SNAP BEANS, SOMETIMES I would like to add sweet corn and snap beans to the list of easy-grow vegetables, but in some regions there are problems with these vegetables. Corn earworms can infest the ears, although the worms destroy only a small part of the ear and can be cut out before boiling without much trouble. If you roast your corn in the shuck, however, it is not very appetizing to open the shuck and find a couple of roasted worms inside as well. In our area, we seldom are troubled with earworms, but the raccoons make growing sweet corn useless if you don’t put an electric fence around the corn. And that’s high maintenance. Where snap beans don’t become infested with Mexican bean beetles, they are very low maintenance. Usually the beetles don’t get bad until the supply of beans is diminishing. The trick then is to mow off the plants about 4 inches high—or as high as you can set your mower. Your mower should have killed many of the beetle larvae on the old leaves, and you can gather up the shreddings and burn them to eliminate the rest. If the weather is not too dry, the plants will grow back and set another smaller crop. This second crop will usually be much less infected, maturing in the later, drier part of the summer, which is usually too hot and dry for bean beetles. Low-Maintenance Cultivation We are going through another wave of popularity for intensive raised- bed gardening right now. This happens about every 30 years. Gardening on raised beds is fine, but it’s not low maintenance. And though all garden writers will rise up to smite me in a high dudgeon with their spades, raised beds are not practical wherever summers tend to be hot and dry, which is most places. If you pile up soil higher than the natural grade, you must be prepared to water frequently, maybe incessantly, because those beds will dry out faster than conventional soil surfaces. The natural capillary action of the soil drawing up moisture from below is disrupted by raised beds. Subsequent necessary watering takes time, is wasteful, and costs money not necessarily recovered by intensive double and triple cropping. More over, much more hand weeding is required. Intensive raised-bed gardening is practical only where space is very limited. The typical backyard is ample enough for a garden without raised beds—with room enough between rows to cultivate weeds with a hand- pushed cultivator or a motor-driven tiller. After the soil has warmed up well (about July 4 is the best time to do this in the North) and the weeds have been cultivated several times and the soil subsequently aerated, apply leaves and grass clippings you have saved as mulch. You’ll find that most of your garden maintenance work is finished for the year. The main reason for putting your garden in rows wide enough for some kind of mechanical weed control is that at the same time you can greatly reduce hand weeding in the row by rolling dirt from the passing cultivator blade against the crop plants and covering small weeds there. The art of covering weeds is ancient, but in these days of herbicides, it seems to have been forgotten. When you plant a crop or row of vegetables, you cultivate weeds several times before planting, and if the ground is warm enough for prompt germination, the crop plants usually get a head start on the next wave of weeds. If not, as in the case of slow-germinating carrots, you will have to weed by hand in the row once or perhaps twice. But whatever, once the crop plants are about 2 inches tall and the weeds only an inch tall or less, rolling dirt into the row with the cultivator will bury weeds and not harm crop plants. The depth and speed of the cultivator determine how much dirt is rolled. In loose dirt, you can experiment with the art by using a simple hoe, pulling it along the side of the row, and letting dirt flow in around the plants as the blade plows along. Even with just a hoe, you can weed a row quite swiftly this way. A few weeds will still come up around the crop plants, but not many. Cultivators

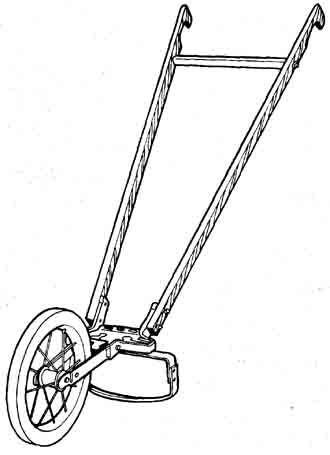

Rows need not be wide to accommodate hand-pushed mechanical cultivators or the newer small motorized tiller-weeders. A hand-pushed wheel hoe of the Planet Jr. type needs only 8 inches of space between plants (although it is better to make the rows wider—at least a foot to allow for the expansion of the plants). The centuries-old Planet Jr. wheel hoe is now called the Jupiter Wheel Hoe and can be found in many gardening catalogs. The handles come back at a lower angle to the wheels than most push hoes, making the hoe easier to push than other large wheel hoes, but both kinds are quite suitable to the task. Hilling attachments are available for all, and most of the shovel or tine types of cultivators will roll dirt into the row. The small motorized tiller-weeders require hardly more than a foot of row space for passage. Mantis (Mantis Manufacturing Company, 1458 County Line Road, Huntingdon Valley, PA 19006) and Sunbird (Sunbird Products, R.D. #4, Box 462, Middlebury, VT 05753) are two well-known ones, and because of their current popularity, by the time you read this most of the tiller manufacturers will no doubt be out with their own versions. If you have a conventional tiller for primary cultivation, you can also use it for weeding as crops grow. By removing the outer tines, you can use it to weed between narrower rows. Most conventional tillers have optional hiller blades that not only roll dirt to cover weeds effectively, but also to do more pronounced hilling, as for potatoes. |

Prev: Trees and Shrubs |