During the summer of 1973, the U.S. economy was booming. We were all whizzing down the highway at 70 miles per hour, the legal speed limit. Gasoline was about 39 cents per gallon, and the posted price of Gulf crude oil was $2.59 per barrel. That year, my wife Lea and I had purchased a lovely old Vermont farmhouse, heated by a coal- stoking boiler that had been converted to oil. The base of this monster boiler was about three feet by six feet, and when it fired, it literally shook the house. We tapped our domestic hot water directly off the boiler, so we had to run the unit all four seasons: Every time we needed hot water, the boiler in the basement fired up. We were burning about 2,500 gallons of fuel oil each year, and in the coldest winter months, it was not unusual to get an oil delivery every two weeks.

Since we had no other way to heat our home, we were entirely dependent on the oil-gobbling monster, and on our biweekly oil de liveries to survive the Vermont winter. Our only alternative source of heat was an open fireplace. Though aesthetically pleasing, the fireplace actually took more heat out of the house than it gave off.

At that time, I was the vice president and general manager of a prefabricated post-and-beam home operation. Like others, I shared the industry opinion that the heating contractor’s job was to install the heating system that the homeowner wanted. As designers and home producers, we were not responsible for that part of new home construction. Home building plans were typically insensitive to the position of the sun. Our prefabricated home packages were labeled simply “front, back, right side, left side,” not “south, east, west, north.” We offered little or no advice on siting, except that we needed enough room to get a tractor—trailer to the job site.

To give you an idea how little energy efficiency was considered in house design (an area of home construction that has since received enormous attention), our homes had single glazed windows and patio doors; R-13 wall and R-20 roof insulation were considered more than adequate. (“R” is the thermal resistance of any housing component; a high R-value means a higher insulating value. Today’s homes typically have much higher R-values.) Homeowners in the 1970s rarely asked about the R-values of their home components, and our sales discussions were less about energy efficiency than about how the house would look and whether it would have vaulted ceilings.

The point is, we were not yet approaching the task of design and construction in an integrated, comprehensive way. We had not yet recognized that all aspects of a design must be coordinated, and that every member of the design team, including the future resident, needs to be thinking about how the home will be heated from the first moment they step onto the site.

THE OIL CRISIS

In 1973, an international crisis forever changed the way Americans thought about home heating costs. After Israel took Jerusalem in the “Six Day War,” Arab oil-producing nations became increasingly frustrated with the United States’ policy toward Israel. In the fall of 1973, these oil—producing nations began to utilize oil pricing and production as a means to influence international policy. In October 1973, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) met and unilaterally raised oil prices 70 percent. The impact of this price hike on U.S. homeowners who heated with oil was spectacular. Fuel oil prices soared.

Then the oil embargo hit. In November 1973, all Arab oil-producing states stopped shipping oil to the United States. By December 1973, the official OPEC member-price was $11.65 per barrel—a whopping 450 percent increase from the $2.59—per-barrel price of the previous sum mer. Iran reported receiving bids as high as $17.00 per barrel, which translated to $27.00 per barrel in New York City.

In addition to giant price increases, oil supplies became uncertain and the United States, which depended on foreign oil for fully half its consumption, was facing the real possibility of fuel rationing for the first time since World War II.

Richard Nixon was president, and his Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, spent most of that winter in what was termed “shuttle diplomacy,” racing from country to country attempting to bring a resolution to the crisis. He didn’t succeed until March 18, 1974, when the embargo against the United States was lifted. It had lasted five months.

As the international oil crisis was played out over those five months, every oil delivery to our home was marked by a price increase, invariably without notice. Worse, our supplier could not assure delivery. My wife and I had two small children, an energy dinosaur of a house, and no other way to keep warm but to burn huge amounts of oil. We couldn’t even “escape” to a warmer climate, because there were long lines at the gasoline pumps. We had never felt so dependent on others as we did that winter. It was plain scary!

THERE HAD TO BE A BETTER WAY

I have a background in engineering, and the energy crisis of 1973 - 1974 provided an incentive for me to investigate solar heating. It was obvious to me that as a country, we had forgotten the basics of good energy management. I just knew that there must be a better way to design and build houses that would capture the sun’s heat and work in harmony with nature. I also have a background in business, and I realized that the energy crisis had opened up a market ready for new ideas about how to heat homes. The energy crisis had shaken us all into action.

The years immediately following that energy crisis saw a remark able emergence of new ideas about solar energy. Solar conferences were held, and the public was treated to frequent articles that described new solar home designs in popular magazines. The results of this collective effort were largely positive. Many new ideas were tested. Some succeeded, and others failed, but building specifications focused on energy efficiency developed during that time have now become standard practice. For example, double-pane high-performance glass is now used almost universally in windows and patio doors. Standard wall insulation is now R-20. That was previously the roof standard; standard roof insulation is now R-32. The science of vapor barriers took huge leaps forward, and highly effective vapor barriers are now standard. Exterior house wraps, such as Typar and Tyvek, are applied on most new construction to tighten up air leaks. Appliances are now more energy efficient. Heating systems have undergone major improvements. These days, it is even common for “smart houses” to monitor lighting and to turn lamps and heating equipment on and off ac cording to need. In sum, we are now building better energy-efficient houses, in large part due to the wake-up call we got in the winter of 1973 - 1974.

WHY FEAR SOLAR?

Unfortunately, as we near the end of the century, it seems that we might be suffering from collective amnesia. We still import more than half of our oil from foreign sources. State by state, we see the speed limit raised back to 1970s levels; some states have eliminated speed limits entirely. A Vermont utility recently announced a plan to reward consumers who use more electrical energy this year than last year. Are we headed toward another energy crisis?

Back in the 1970s, I designed and patented what I saw as a partial solution to the energy crisis—an innovative solar house design. All of our homes, as far south as North Carolina and as far west as Kansas, are still functioning as well today as when they were first built. This design will work for you, today.

And yet from my work building solar homes over the past twenty years, I’ve found that people resist solar for four main reasons. They are afraid that the house will get too hot. They are afraid that the house will be too cold. and they are afraid that a solar house has to be ugly and futuristic-looking and will require expensive, fickle gadgetry and materials, with walls of glass, or black—box collectors hanging from every rooftop and wall. None of these fears are well-founded.

The design and building strategies presented in this book are carefully engineered for building solar homes with traditional features, while incurring no added expense in the process. The solar approach is really a rearrangement of materials you would otherwise need to build any home. In fact, the only feature you sacrifice using this design is a basement, but you gain so much in energy savings and by living in a large, cheery, well—lit place, that I think that you’ll find this trade-off is more than worthwhile.

Here are a couple of other considerations to keep in mind when reading this book. First, I came to the design and building of solar homes as a businessman and engineer, and this book reflects that approach. I’ve aimed for a practical, step-by—step, how—to treatment. Every building strategy presented in this book has been proven out in the real world.

Moreover, though I’ve chosen one type of design to describe in detail, this book also offers a wealth of practical information for de signing any solar home, whether you use the Green Mountain Homes approach or not. A wealth of engineering data is included in the hopes that this book will become a welcome addition to any complete library of solar design.

GREEN MOUNTAIN HOMES: A SOLAR SUCCESS STORY

The ingredients for my decision to go into the business of designing and manufacturing solar homes were all in place just after the oil crisis hit. My engineering and home manufacturing background offered the stepping-off point. I had been doing research on solar designs through out 1974, and by mid-1974, the idea of starting a business devoted to producing pre—fabricated solar homes seemed more exciting than ever before. The concepts for the business and formulation of the solar de sign were finalized by late 1975. Green Mountain Homes was incorporated on January 1, 1976, and was the first United States home manufacturer dedicated solely to designing and manufacturing solar homes in kit form. I purchased twenty acres of commercial property in Royalton, Vermont, and in June 1975, left my job as vice president and general manager of the prefabricated post-and-beam home operation.

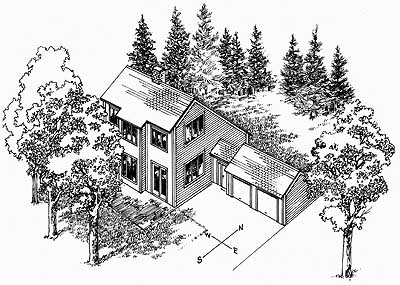

Siting a house with sensitivity to the sun’s daily and seasonal patterns, and using conventional materials wisely, you can build a traditional-looking

solar home that largely heats itself.

The Green Mountain Homes factory practiced the lessons we preached: the building where our houses were fabricated was itself solar-heated, energy-efficient, and largely lit by daylight.

In January 1976, I visited Sheldon Dimick, the president of the Randolph National Bank in Randolph, Vermont. In the business proposal, I included plans for a dozen affordable solar homes. My wife Lea, with her Middlebury College art background, had drawn pencil renderings of the homes, which later became the basis for our first brochure. Sheldon, my banker, was immediately taken by the idea. In just a few weeks, we had put together a financing package with his bank, the Vermont Industrial Development Authority (VIDA), the Small Business Administration, and a personal loan backed by our farmstead, the one with the oil-thirsty boiler in the basement. The irony did not escape me that my energy dinosaur of a house was helping to finance an energy-efficient housing business.

While I was arranging private funding to start Green Mountain Homes, a business that would ultimately design, fabricate, and ship almost three hundred solar homes, the state and federal governments were getting involved in solar, offering tax incentives to encourage use of solar energy. The U.S. government spent on the order of a quarter of a million dollars to install domestic solar hot water collectors over a covered parking lot at a nearby resort hotel, To the best of my knowledge, those solar collectors have long since been disconnected because of mechanical problems and leaks. The state of Vermont, with some other states and the federal government, was instituting tax credits for investments in solar technologies. But credits were offered only for add-ons and retrofits of existing homes. These credits were for the “additional equipment needed,” in the state’s view, to provide solar energy. As a result, passive solar homes like the ones I intended to sell were almost completely left out of the tax-credit programs. Green Mountain Homes’ buyers had difficulty obtaining solar credits, since the principle of my design was to utilize and rearrange the materials that you are already committed to purchase for building any style of new home, solar or not. Fortunately for my buyers, nighttime window and patio door insulating devices, extra insulation, and elements of the solar control system were considered add-on features and therefore qualified for solar credits. Yet the credits thereby earned were never significant enough to be the motivation for us or our clients to build solar homes instead of conventional ones. The real incentives were the ease, reliability, and comfort derived from solar heating. Paradoxically, since the solar water—heater collectors at the nearby resort were an add-on feature, the resort probably got more money from the U.S. government through solar credits than all of the Green Mountain Home solar homeowners combined. The federal government’s solar subsidy program was completely dismantled during the Reagan years.

A MODEL HOME and SOLAR FACTORY

When I was first working on my solar home design, I participated in a seminar led by Professor A.O. Converse of the Thayer School of Engineering at Dartmouth College. My role in the seminar was to provide the students with practical house construction information. When I explained my plan to build a prototype model solar home, Professor Converse offered to provide independent monitoring, using some of Dartmouth’s resources, with funding and equipment supplied by the local power company, Central Vermont Public Service.

Construction of Green Mountain Home’s solar-heated factory and the model home, which also served as my office and sales center, began in March 1976.The design was so successful that the energy savings (in both heat and electric lighting costs) paid the real estate taxes on our twenty acres each year.

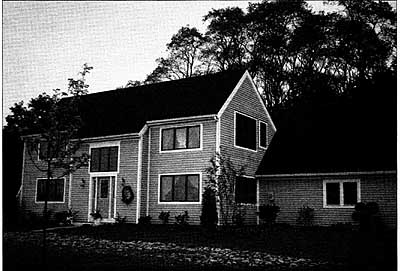

A Green Mountain Home built in 1984 and located in northeast Pennsylvania.

With our borrowed money, we started an advertising campaign. We also decided to erect a state—approved off—site road sign on one of Vermont’s major interstate highways, indicating the location of our business. The Vermont state highway department objected to the placement of the sign, so I asked my wife, Lea, to represent us at a hearing in Montpelier. As Lea was explaining the need for our placement of the sign, she described our new solar home business. A woman who sat on the board was so impressed with the idea that she sent her son to see us. He liked what he saw, and his home was delivered early in the fall of 1976.

Not long after, Lea was working in her mother’s grape arbor and noticed a stranger approaching. He had seen an ad for Green Mountain Homes in a magazine, but the return address was to our home, not our factory/model-home complex nearby. The gentleman explained that he had spent most of the day looking for Green Mountain Homes and had finally stopped at the post office for help. Since ours is a small town, the postmaster knew about our new venture and sent the gentle man to my mother-in-law’s home. By coincidence, Lea happened to be there. It turned out that the gentleman was a graduate of Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and was most supportive of our new solar home business. His home was delivered late in the fall of 1976; he has always maintained that he was the first buyer, because he ordered his home first.

Green Mountain Homes was launched. The company doubled in size yearly, and we were often hard pressed to keep up with the workload. I can remember many a Christmas when we were late to our own party because we were loading a tractor—trailer with that year’s last home.

Potential buyers almost always traveled to Royalton, Vermont, to examine the model solar home, and to attend my Saturday morning solar heating seminars, which were followed by lively question-and- answer sessions. It was fun. Our customers came from all walks of life, and they accepted this new technology with enthusiasm. One man

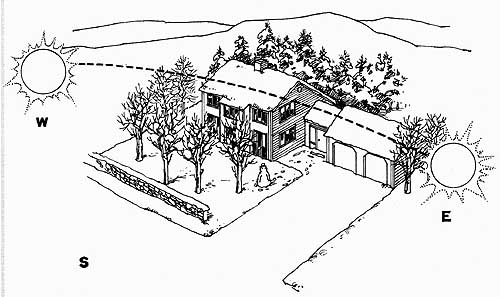

Solar Principle #1: Orient the house properly with respect to the

sun’s relationship to the site.

Use a compass to find true south, and then by careful observation site the house so that it can utilize the sun’s rays from the east, south, and west during as much of the day and year as possible. In orienting the house, take into account features of the landscape, including trees and natural land forms, which will buffer the house against harsher weather or winds from the north. Deciduous trees on the sunny sides of the site will shade the house from excess heat during the summer months, but will allow the winter sunlight to reach the house and deliver free solar energy who bought a Green Mountain Home was asked to speak about it to the local Rotary Club. He protested, claiming that he didn’t know how his house worked. Since he had a good sense of humor, the Rotarians thought he must be joking, so they asked him to speak any way. The fact is, he really didn’t know how his house worked, even though he and his brother had built it from our kit. When the Rotarians asked about the house’s operation and about how much work he had to put in to keep it heated, he informed them that the day after it was completed, he had set the thermostat on 68 degrees and hadn’t touched it since. This man had called me shortly after moving in to let me know that he and his brother had forgotten to put in the second floor heating ducts. and the house was still warm. We learned from our customers as we went along; in this case we found out that we could cut back on ductwork.

NEWS OF OUR SUCCESS SPREADS

Since Green Mountain Homes was a private venture financed through conventional bank loans, we had to succeed on our own merits with out public or government funds. and we did succeed, because the design worked so well, both in tests on our prototype and in the com fort it delivered to the people living in actual homes, We also tried to help advance the solar movement by speaking at our own expense at various meetings and conferences. Our success story was featured in dozens of publications, including Solar Age, Better Homes and Gardens, House and Garden, New Shelter, Farm Equipment News, The Muncie Star (Indiana), The Winchester Evening Star (Virginia), The Boston Herald, The San Francisco Chronicle, Money Magazine, and The Sierra Club Bulletin, to name just a few. We also received enthusiastic mail from our customers through the years, for instance this from happy solar homeowners in Bethlehem, Connecticut:

In the winter, we are warm. In the summer, we are cool. There are no unusual contraptions involved to store heat or regulate the temperature. We spent no additional money on “solar features” when we built this home. All materials were available at local lumberyards—nothing exotic. However, it was important to let common sense take precedent. We did, according to our instructions, face the broad, multi-windowed side of our house to the south. (Consequently, we gave up the “parallel to the road.”) The north side has few windows, and many closets, and that side is also sheltered by a wind-block of pine trees. The “heat-producing” kitchen is also placed on the north side of the house. Our floor is made of tile, which absorbs the heat from the sun, so in winter the tile is never cold to our feet, as the tiles and Solar Slab underneath store the warmth. (The reverse is true in the summer, when the tile retains the coolness of the night during much of the day.)

And this letter from Pennsylvania:

One of the greatest satisfactions about our home is that even though we are designed to be solar energy efficient, it placed very little restraints on how we designed the floor plan. Our home has a real feeling of spaciousness because of the view and use of windows. Even during the horrendous winter of 1993, we didn’t get “cabin fever.”

Green Mountain Homes’ production facility was closed several years ago. I now provide pre-construction, advisory services rather than sup plying house plans. I believe the book provides adequate information for a professional home designer to make the necessary calculations and develop the detailed plans needed to build a solar home.

All of the Green Mountain Solar homes shown in this book are privately owned and are not available to the public. The policy of protecting my homeowners’ privacy was established long ago and has helped to maintain good relations with my clients.

As the patents issued on the solar system described in this book have expired, the design is now in the public domain. The invention now belongs to the “People of the United States.” This book is an effort to make this “gift” more meaningful. Hopefully, it will benefit other solar designer sand future homebuilders.

Good luck with your solar project.

Next: The Passive Solar Concept

Prev: Intro