Low-Maintenance Roofs

| Home | Wiring | Plumbing | Kitchen/Bath |

|

No doubt the most vulnerable part of the house is the roof over your

head. Metal Roofing Having been raised in a society where the change from metal roofing

to asphalt shingles was considered a sign of progress, I am surprised

when every roofer I ask says that metal roofs today are the best buy

for the money of any kind of roofing. This contention is supported

Fine Homebuilding magazine: “The important thing to remember about

metal roofing is that front-end costs aren't as telling as life-cycle

costs. The slate and clay-tile manufacturers will argue that point, especially

since some of the less costly metal roofing does require periodic painting.

But however that argument might be settled, obviously those of us who

have believed that asphalt shingles are the last word in the low- to

middle- priced roof probably ought to reconsider. The biggest objection

I hear to metal is that it's ugly, a charge not as true now as it

once was, and one that's too subjective to mean much anyway. Also, cheap corrugated metal barn roofing gave metal a bad name. That creaky corrugated stuff loosened in the wind and rusted away, if it didn’t blow away. The sound of rain drumming on a metal roof can lull you to sleep; the sound of hail on it can send you flying to your feet. Choices in Metal Roofing Materials Galvanized steel will not hold up well in the salty air of sea breezes. In such situations, a newer product, aluminum- and zinc-plated steel, Galvalume (Bethlehem Steel Corporation, Bethlehem, PA 18016-7699) is advisable. There is another kind of galvanized steel, more expensive and heavier than the standard kind, which isn't painted. Called Cor-Ten (USX Corporation, 600 Grant Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15230), it's deliberately made to rust, the rust forming a protective coating that lasts for many years. The rusty red color is attractive. The only hitch is that runoff water carries some of that color with it and can stain trim or walls. Used with dark trim, this staining may not be so noticeable. Zinc alloy, Microzinc (W P. Hickman Company, P0. Box 15005, Asheville, NC 28813), has a life expectancy of over 100 years without maintenance if installed right. But it expands and contracts more than aluminum and this must be taken into account when installing. It can crack if it's bent in temperatures below 50°E But all things considered, it's a Cadillac of a roof, for those who can afford it. Copper bends easily for easy installation, so it's a dream for roofers. Or so it would seem. But hobnobbing with roofers, I’ve learned even copper has its weaknesses. It will corrode other metals it comes into contact with. And used for flashing, which is a wise move for a low- maintenance home, it must be installed ever so carefully. If in bending it to fit into a valley, the roofer crimps it unduly (rather than fashioning a nice gentle curve), the copper will break in two at the crimp quicker than galvanized steel if there is seasonal structural movement between the two roof planes, as can be expected. Tin solders and bends easier than galvanized steel but will not last as long for flashing. Soldered tin roofs over small flattish areas aren't as durable as galvanized, but any flat roof is asking for trouble. Stainless steel stands halfway between copper and galvanized steel in price and durability. It will pit and spring leaks after a long time. If you are going to spend that kind of money, you might as well step up to Terne coated stainless steel, which is nearly as forever as copper (Follansbee Steel, P.O. Box 610, Follansbee, WV 26037). A roof of plain steel Terne might be the best compromise between cost and low maintenance. If you are a reader of Alex Wade’s books, you know that this sometimes outspoken architect favors Terne, even though it's relatively expensive. In installation, he uses a slightly different design in the standing-seam panels than what I describe a bit later; it requires bending in a machine shop. On-site bending with hand tools using the traditional method I suggest would save considerable money for the do-it-yourselfer. Terne is lead-coated steel and there’s no reason I know of why it couldn’t be bent to shape on-site with traditional tools. As Wade points out, the original Terne roof on Jefferson’s Monticello is still in good shape. And since no one seems to have been harmed by the lead in the coating in all the years that it was lived in, I doubt there’s need to worry in that regard. However, one might not want to drink cistern water off a Terne roof. I am reminded of a farm family I once wrote about whose water supply came from the barn and house for nearly two centuries through lead pipe. The health department finally made them quit using the water in the dairy room, so in anger they quit milking cows instead. And they continue to drink the water as generations of the family always have, apparently unharmed. However, health authorities still insist that lead pipe is a definite hazard. Some newer metal roofing panels are designed so that you can nail or screw right through them; snap-on clips cover the nails or screws and prevent the roof from leaking around them. At least one popular steel panel, Met-Tile ( P.O. Box 4268, Ontario, CA 91761-4268), uses exposed screw fasteners, each with a grommet seal. Met-Tile looks attractively like clay tiles. Well, almost. The coating on the metal, available in several colors, is Glidden Nebelar, one of the premium fluorocarbon resins that the company says will last a good 20 years. Costs Copper is now about $7 a square foot, but copper prices are apt to be volatile. For zinc alloy, I’d figure 30 percent more than copper as I write this in 2009. Stainless steel coated with Terne, an alloy of lead and tin, is third most expensive, being nearly the cost of copper. Plain stainless steel is fourth at about two-thirds the cost of copper; then regular Terne, at a little less than half the cost of copper; then aluminum; and finally galvanized steel at less than 20 percent the price of copper. It is difficult to talk except in general terms about the cost of metal roofing. In most cases, the standing-seam panels will be shaped on site and so the labor costs will add considerably to the cost of the metal itself. If the roof is a very simple one, with few valleys or obstructions like dormers and chimneys, installation is easier and therefore much cheaper than for a complicated multilevel, multi-valleyed roof. With galvanized steel at $65 a square (100 square feet), a roof installed can cost from $90 to $125 a square and up. The only case where standing-seam metal is going to be cheaper than asphalt shingles is in reroofing. The metal can be put on over a couple layers of asphalt shingles. If you are reroofing with asphalt-fiberglass shingles, those two or three old layers of shingles have to come off first, which will cost as much as putting on the new. The lesson in low maintenance favoring metal is obvious. Also, in the case of galvanized steel, which is by far the most common metal roofing installed, there is a broad range of quality and therefore price. You can buy galvanized in various thicknesses (gauges) but the word, gauge, isn't used precisely in the industry, so it's better to use measurements in fractions of the inch, so that both you and the dealer know what you are talking about when it comes to quoting prices. A measurement of .015 inch may seem as but a hair different than .036, but the second is at least twice as durable a roof as the first. Also, the quality of the steel depends upon the amount of zinc in the plating. The more zinc, the more resistance to corrosion. A G90 rating means 1.25 ounce of zinc per square foot, while G60 means .83 ounces per square foot—a big difference in galvanized steel. The table “Cost and Investment Analysis for Reroofing Pitched Roofs” compares various materials. The analysis was done in southern California in 1983, so the costs should be used as a comparison guide only. Costs will obviously vary from one city to another. As such, the table is interesting not only for the re-roofer, but also for those interested in roof values in general. This table is good background for what comes in the rest of this section, because I think it justifies the extra cost of using more durable roofing materials. Note that fire-retardant pressure-treated cedar shakes cost almost as much as clay tile initially, but far more in terms of life cycle yearly costs. Also note that even heavy-duty fiberglass shingles have a higher life cycle cost than the more expensive clay tile. Unfortunately, the more expensive metals aren’t included in the study, nor are any standing seam, although I believe they would have scored quite well economically in life cycle costs. Standing-Seam Roofs Almost all metal roofing is applied by some version of what is called standing-seam design because so far this is the best way to avoid any exposed nails. There are now sophisticated machines to bend and crimp the fiat metal into standing-seam panels, but many roofers still do the work with traditional hand tools. The metal is usually shaped on site, as this is the better way to keep from wasting any. A roofer calls down the precise length of panel he needs, his helpers cut it from the roll, then the edges are bent up by hand or machine. The brainwork of the process was all done years and years ago, and actually learning how to do it now is mostly a matter of spending a couple of days working for a roofer, as I did. In this case, the teacher was my son, so we reversed the usual order—a young man passing on to an older one a traditional skill. We used the old traditional hand tools, which are somewhat slower (but not much) than an expensive roll-forming machine. Nevertheless, a homeowner is likely to get the job done cheaper by the kind of people who use the traditional tools because they don’t have expensive machinery to pay for and usually don’t charge as much for their labor.

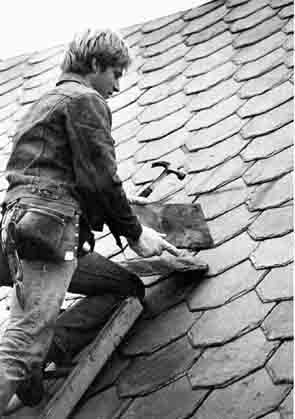

Painting a Galvanized Steel Roof If you buy galvanized steel already painted (a wise purchase in my opinion), it will cost about 30 percent more than unpainted galvanized. The advantages of prepainted galvanized are many: First, it will mean that all the metal is coated with paint, even the edges, which are bent and crimped into the standing seam where you can’t paint once the roof is installed. Second, it saves you from clambering up and down a smooth, slippery roof after installation, painting it. Third, unpainted galvanized steel from the factory has an oily coating that must be removed before paint will stick. Factory-painting does a better job of removing that oily coating and applying paint. Once the roof is up, what most people do is wait about a year before painting these unpainted roofs so that the oil weathers off. This practice also applies to chromate coatings on imported galvanized steel, which must be brushed off or weathered off before paint can be applied. (If you want to clean the oil off a new galvanized steel panel, scrub it vigorously with a strong, hot solution of trisodium phosphate and then rinse with vinegar. Scrubbing well is important. A friend of mine evidently didn’t do a sufficient job of scrubbing hers, because the roof has had to be scraped with a wire brush and then patch-painted three times in five years in spots where the oil was not entirely removed.) Improved paints for galvanized steel are now available. After the oil film has been cleaned or weathered away, put on a primer of zinc chromate, or the older treatment, red iron oxide. Then apply the finish coats in the color of your choice. This may be an enamel for metal, or better, a silicone-modified polyester, which should last 20 years, or better yet, a fluorocarbon resin. There are newer and more expensive coatings, one with ground copper particles suspended in the fluorocarbon resin, and another of acrylic film called Korad (Polymer Extruded Products, Inc., 297 Ferry Street, Newark, NJ 07105). For information on suspended copper coatings, check with Berridge Manufacturing ( 1720 Maury Street, Houston, TX 77026); and Architectural Engineering Products ( 7455 Carroll Road, San Diego, CA 92121). For fluorocarbon coatings, see Penwalt Corporation (Plastics Department, 3 Parkway, Philadelphia, PA 19102); and PPG Industries, Inc. ( One PPG Place, Pittsburgh, PA 15272). Slate Roofing The way to prove the durability and low maintenance of various building materials in my rural area is to observe abandoned houses in the country, of which, sad to say, we have many. The ones that stand the longest without any care at all, until the bulldozer gets them or some loving restorer brings them back to life, are brick houses with slate roofs. If the slates are the gray kind, what we call Pennsylvania slate, they are most often rotten by the time they are 100 years old. If they are the red- or green-hued kinds, what we call Vermont slate, most of them are good for another 100 years at least. My son salvaged enough to cover the front half of our woodworking shop. With a little practice, you can tell in an instant if they are reusable by tapping them with a hammer. A crisp ring means the slate is still good; a duller thud means it's rotten or cracked. Sunlight finally rots slate—ultraviolet light eventually will get just about everything. But salvaging Vermont slate is a very profitable practice. Roofers usually charge about 50 for a good old slate of 12 by 24 inches. New pieces of Vermont slate cost up to $5 each. I have seen some new slate from Spain priced as low as $286 a square (100 square feet), but it's quite thin compared to the old (and new) Vermont slates. But even at $300 to $400 a square, slate is a good long-term investment.

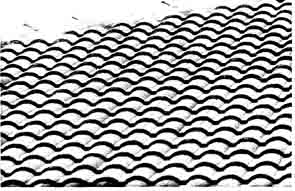

Installing slate is much easier than I expected. The slates I have seen from Spain have pre-drilled holes for the nails, but what we use you can drive a nail through just like through a board. It is better, even, to hit the nail a good crack the first time to drive it in, rather than tapping on it gently in fear of cracking the slate. You really should use copper nails, at least 11 gauge. On many old slate roofs, if copper nails were not used, the nails gave out long before the slate, and the roof deteriorated on that account. Slate cutters, which resemble and work about like paper cutters, make sizing a slate for any particular spot an easy operation. Some roofers believe slate will last longer if it's nailed over thin battens that raise the slates off the sheeting a bit, allowing air to circulate between slate and underlayment. Others contend that just the way the slates lap each other provides enough air space for good circulation. Manufacturer specifications I have seen do not require such battens, but only a “cant strip” under the first course to tilt the slates up so that subsequent layers will lap down tight over them. This is standard procedure for laying any kind of roof tile. With slate, the outer roof edges need to be covered—aluminum stripping is most often used now. (If you need general directions on how to install any roofing, read the manufacturer’s specifications on the backs of the brochures that advertise their wares, and you will find a whole lot of valuable instruction, all for free.) Slate roofs are extra heavy (and if they’re loaded down with snow, even heavier). In fact, on some roofs you may need snow and ice arresters. Consult an architect or building engineer for your particular case. I have seen old slate roofs painted, a horrid practice, but where money is short and the slates leaking, it's a stopgap measure that will buy some time. There are, in fact, all sorts of plasticized products marketed in recent years that will supposedly waterproof almost anything. Some of them are as expensive as putting on a new roof. Vitrified Clay Roof Tiles Fired clay roof tiles, like fired clay bricks, are one of the most durable and maintenance-free materials made by man. These products not only result in consummate beauty, durability, and low maintenance, but they also appeal to the best in humankind. Their very existence in our society bespeaks stability and art. Clay-tile manufacture, for example, has been in decline basically because the “throwaway house” has been fashionable. Throwaway houses are built by throwaway societies, made up of people with no sense of the wisdom of past knowledge, so laboriously learned, and little care for the future. Building with stone and baked clay does not really require money (although lots of money for them is what the times now demand), but to a commitment to a place and a mastery of traditional skill. I ate in a restaurant yesterday that was built of bricks handmade on the place 100 years ago. A month ago, I interviewed a farmer who lives in a brick home, the clay for which came from the garden—100 years ago. Anyone who can bake bricks can bake roofing tiles even easier, and for centuries in other parts of the world, roofing tile was “homebaked,” along with the bricks. Stone and clay demand craftsmanship. You couldn’t even put a heavy clay-tile roof on a throwaway house; it might collapse. In a clay-tile factory, what you find, surprisingly, is still lots of handcrafting. That’s one reason clay tiles are expensive. At the Ludowici-Celadon clay-tile factory at New Lexington, Ohio (Ludowici-Celadon Company, 4757 Tile Plant Road, New Lexington, OH 43764), known worldwide for its work, I watched three people turning Out one of the many styles of tile produced there—Americana. One operated a machine that pressed out the tiles in the wet clay. The other two workers took the individual tiles from the press and trimmed away the excess clay, punched in the holes for the roofing nails, and rubbed the surface smooth—all by hand. They could each work on 500 a day. In another part of the factory, a machine can press out, without help, 11,000 tiles of the Spanish style per day. Obviously, the machined tiles will cost considerably less. Ironically, because there is more demand for the Spanish than the Americana (the Americana is much more beautiful, I think, but the Spanish is better known), the factory can afford to automate for the Spanish, but not for the Americana. In other words, people don’t buy Americana clay- tile roofing because it's too high priced, and it's too high priced because so few will buy it! Colors and Styles in Tile After viewing and reviewing all kinds of roofing, I went to the Ludowici-Celadon tile factory because it's the only one I know of and the only one within easy driving distance. When I saw the variety and beauty of clay tiles made there, I was, plainly speaking, overcome. No other materials I’d seen, including slate, which I like a lot, came close to equaling the beauty of the clay-tile designs I saw laid out there. Hitherto I, like most Americans, thought of clay tile in terms of what you see on Taco Bell fast-food restaurants, and that doesn’t particularly appeal to me. Ludowici-Celadon’s Spanish-style tile was, first of all, darker than what you see on Taco Bells, a definite improvement. But that was only one of a surprising variety of styles and colors available. I’m going to take the time to mention most of them because I’m sure most of us aren’t aware of them. Among the standard styles available are: Americana, French, Imperial, Lanai, Norman, Spanish, Straight Barrel Mission, and Williamsburg Classic. Here’s a sampling of the colors available (not all colors are avail able in all styles): Aged Cedar, Barcelona Buff, Beach Brown, Brookville Green, Colonial Cedar, Coral, Earth Gray, Fine Machine Scored Red, Fireflash in three shades of brown, Forest Green, Hand Rough Aged Cedar, Hand Rough Colonial Gray, Hand Rough Forest Green, Hawaiian Gold, Lava Black, Mediterranean Blue, Norman Dark Black, Norman Light Black, Norman Medium Black, Pacific Blue, Red, Sunset Red. Or, if you want to pay extravagantly, you can have a color custom made. For example, Beaver Creek Lodge near Aspen, Colorado, wanted a blue roof like one the owners had seen in Andorra in northern Spain, but which they could not find the likeness of produced anywhere in Europe. It took Ludowici-Celadon six months to develop the color, which they now call Beaver Creek Blue. Some of the tiles are terribly expensive because the individual tiles are smaller, and it takes more of them to cover the same amount of space. Norman is an example; it makes, in fact, the most beautifully textured roof I have ever seen. It costs, hold your breath, over $1,000 per square (100 square feet). Also, some of the color glazes, like Brookville Green and Mediterranean Blue, available on only a few styles, cost from $800 to nearly $1,000 a square. The Spanish style in red costs about $250 a square, which makes it reasonable for a good moderately priced home. Other styles in a good choice of colors sell in the $300-per-square range. Still other choices are available in the $400- to $500-per-square range. Not all clay tile on the market is necessarily of high quality. If fired in the 2,050°F range, the tiles are strong and durable. If the top firing degree falls below that, the tiles will be weaker. Some clay tile, and American tile makers like to throw the adjective “imported” into that statement, is fired at lower temperatures. They may last a long time in mild, dry climates, but not necessarily in the extremes of northern North America. Ludowici Celadon guarantees their tile for 50 years, and they have a life expectancy of well over 100 years. Terra cotta and fire clay aren't the same; the former is made from special shales with perhaps some fire clay added. In general, terra cotta is used for more massive architectural details—pillars, gargoyles, etc. On the other hand, fire clay, which is used for roof tile, has little or no shale in it— just clay and water and a little barium carbonate so the tile surface on the roof doesn’t get scummy.

Tile Manufacturing: A Fading Art The area around New Lexington and Zanesville in east-central Ohio has long been noted for shales and clays perfect for all kinds of ceramic products, which explains why Ludowici-Celadon’s last factory (originally there were five scattered across the country) is here. The shale and clay are plentiful and often available as a by-product of coal strip-mining, which then makes them cheaper yet. Labor and the fuel to heat the kilns are the two major expenses. Some clay-tile manufacturers are very small—little more than cottage industries that contract a certain amount of work each year more as artisans than factories. In a declining market that attracts only the wealthy or the very tasteful, making roof tiles becomes each year more art than manufacture, just as it does at Ludowici-Celadon, whose work force is down to about 75 people now. As far as I know, there are few or no retail outlets for clay roof tiles. With Ludowici-Celadon, you deal directly with the company, through regional salespeople or with someone at the factory. Tile’s Insulative Value Like brick or concrete, clay-tile roofs have no insulative value to speak of, but they do act as a heat- or cold-storage sink. In the winter, they keep buildings warm by absorbing heat during the day and radiating it back at night. In summer, they cool off at night, helping to keep the building from getting too hot too soon during the day. They even out temperature variation and with a particularly heavy, bulky roof style like Norman, the effect can be quite significant. Concrete Roof Tile If you can’t afford real clay tile, you may want to consider concrete ones that now come in a few colors and styles that make them look remarkably like clay tiles. The forerunners of these tiles were the asbestos concrete roof shingles, which were very popular 40 years ago, before asbestos got its bad reputation. Johns Manville sold them as a “lifetime roof,” and plenty of them remain as good as they ever were, so long as no one carelessly walks on them. They crack very easily Actually, tests have not indicated any danger from old asbestos concrete roofing shingles to builders or homeowners if manufacturers guidelines are followed. The concrete locks in the asbestos fibers, maintain the manufacturers, and can’t be released into the atmosphere unless sanding, drilling, or scraping the shingle takes place—all of which aren't recommended. As of 1986, some of these very long-lasting shingles were still being manufactured, all quite legally. If interested, one company to contact is Supradur Manufacturing Corporation (P0. Box 908, Rye, NY 10580). Most of today’s concrete tile doesn’t have asbestos in it and is certainly a thousand times more beautiful to look at. Why it has not enjoyed popularity so far except on the West Coast and the Southwest is hard to explain. Its low-maintenance advantage would seem to make it a good candidate for anywhere. The Marley Roof Tiles Corporation (1990 East Riverview Drive, San Bernardino, CA 92408 or 1901 San Felipe Road, Hollister, CA 95023) for example, offers concrete tiles in Spanish style in gray, charcoal, burgundy, clay red, brown, and alpine; an “Old English Slate” in gray, red, and brown; and a “Western Shake” in gray, alpine, and brown—all with 50-year limited warranties. The company also offers a new, lighter-weight concrete tile called Duralite, which weighs about half that of normal concrete. These tiles can sometimes be installed right over old roofing, too. Detractors say that the colors in concrete tiles do fade after 15 years or so, despite manufacturers’ claims, but a lot of the new materials haven’t been around long enough to tell for sure. The only reason I am not thrilled with them is that I have had some experience with concrete drainage tile compared to fired clay drain tile. The latter will just about last forever in the ground. Concrete, in the same situation, tends to absorb moisture and rot, crack, and cave in after 15 or 20 years. But, as asbestos concrete shingles have proved, this isn’t necessarily so on a roof.

Asphalt-Fiberglass Shingles You learn the weaknesses of a product when its manufacturer de scribes it after another product is developed to take its place. For instance, asphalt shingles used to be described as having an “organic mat base.” But now that asphalt-fiberglass shingles are being promoted in place of plain asphalt ones, the manufacturers tell us that the latter had “merely a cardboard base.” A fiberglass mat, being inorganic, isn't supposed to deteriorate as quickly as mere cardboard. The fiberglass, so the manufacturers say, also will hold more impregnated asphalt and ceramic-coated granules in the asphalt. So it will last longer—with up to 30-year prorated warranties. None of that kind of talk tells the whole truth. But maybe the whole truth isn't possible. Up into about the ‘60s, you could buy a good, heavy asphalt shingle with a “mere cardboard” base that would last 25 years, and I personally know of some that did. “Heavy” is the key word. On the other hand, the fiberglass on our roof, which is supposed to last 30 years, isn't going to make it to 20, a roofer tells me. One thing that happened on the way to “improve” asphalt roofing was to put a dab of tar on each shingle so that the overlapping shingle will stick to it when the sun burns hot on the roof. Once stuck down, the shingles will not flap in the wind. This is probably a good idea, except that it enables manufacturers to make thinner, lighter shingles because they figure that the shingles can depend upon the dabs of tar to hold them down instead of their weight. Now you have to worry about whether they will stick down before they blow away—no small worry if the roof is put on in cold weather. And either way, you still have a light shingle; I don’t care what it's made out of. Light shingles equal high maintenance. Your best alternative is to invest in the heaviest fiberglass shingles available—some have two layers of fiberglass mat. These thicker shingles are the more attractive—in line with today’s fashion for a heavily textured roof surface. Top-of-the-line fiberglass shingles aren't cheap by any means, but they are cheaper than wood shakes, clay tile, or good metal. And they have a class-A fire rating. If you refer to the table “Cost and Investment Analysis for Re-roofing Pitched Roofs,” you will note that in life cycle costs per year fiberglass and asphalt shingles are two of the most expensive roofs. The same old question rears its head and only you can decide. With roofs, you’ve got some of the same options you have when making other home-supply purchases. It is going to cost you so much to keep the rain off your head, no matter which you choose. You can spend it once and be done with it, or you can spend it three times and worry about it in between. Where roof shingles (of any material, but perhaps most of all asphalt and fiberglass) are laid on a relatively low-pitched roof, leaks can occur when ice forms at the roof edge, stopping the flow of melt water off the roof and backing it up under the shingles. A layer of roofing felt over the plywood sub-roof deals with this problem fairly well. At the very least, this felt flashing strip should be placed down before the shingles are installed from the edge of the roof back to at least a foot inside the vertical wall line. There’s a new type of roll waterproofing flashing made specifically for this purpose. It’s called Ice and Water Shield (W. R. Grace and Company, 62 Whittemore Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02140). It is self-adhesive underlayment, and it bonds to both roof deck and shingles and seals around nails, making it almost impossible for water to seep back under or through it. Wood Shakes If you took a poll, cedar shakes would probably rate as America’s favorite roofing, especially by those who don’t have them. Beautiful they are, but beyond that there is little to praise them for. Untreated cedar shakes are somewhat cheaper than the pressure-treated ones, but they are rather short-lived. Even treated, cedar shakes need regular maintenance, and in humid climates the thinner ones aren't any more durable than asphalt. Pressure treated, they become as expensive as some clay tile, though much shorter-lived. Therefore, their annual life cycle cost is very high. One feels like a traitor, pointing out maintenance disadvantages in America’s dream roof. What can I say? There are companies in the Northwest, where western red cedar comes from, that make an entire business of caring for cedar roofs and siding. The cost of replacing a cedar roof, according to 1980 statistics, was about $3 a square foot, and probably a bit higher right now. If you protect it with something like Flood’s Roof Grade protective clear wood finish for cedar shakes (The Flood Company, P.O. Box 399, Hudson, OH 44236), you will need to redo it about every five years, says the manufacturer. Crews usually spray on the treatments. With such high maintenance, the shakes could last a long time. The Flood Company has a shingle they like to show, which was treated with their products years ago and which remained in good condition under adverse weather conditions for over 40 years. They don’t have a whole roof of them, however. Standard handsplit and resawn shakes come in 18- and 24-inch lengths, in 1/2- and ¾-inch thicknesses. Treated, they weigh from 250 to 350 pounds per square (100 square feet). Pressure treatments are usually both fire retardant and weather resistant. Their fire rating is still only class C, although the Koppers Company, Inc. ( 436 Seventh Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15219), has a patented system whereby their cedar roofs have been upgraded from a C to a B rating. The shakes are mounted over Koppers’ plastic-coated steel foil and a minimum 1 plywood deck or 2-inch nominal and thicker tongue-and-groove decking. |

| HOME | Prev: In Search of the Low-Maintenance House | Next: Doors and Windows |