Low-Maintenance Floors and Floorcoverings

| Home | Wiring | Plumbing | Kitchen/Bath |

|

Since floors take the most wear and tear in the house interior,

the choice of flooring materials is of high priority for the low-maintenance

house. The first consideration in making that choice is the one usually

considered last, if at all, and it applies not only to floors, but

to the rest of the house interior as well: One must have clearly

in mind the difference between quality as expressed by durability and low maintenance, and value as expressed by fashion and taste.

A true story most recently reported in Remodeling World (November 2007), a most helpful magazine for owner-builders and remodelers by the way, illustrates the point. When the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts was remodeled recently, architect Hyman Myers discovered that the white plaster columns in the interior galleries covered ornate Victorian cast-iron columns. The plaster was laboriously and painstakingly removed and the original pillars repainted to their original colors, the result hailed as a triumph of authenticity over sham. No doubt. But the original columns were covered because they came

to be considered if not downright ugly, at least unfashionable. I

can just hear an interior decorator at the turn of the century justifying

the plastering of the ornate columns by saying that all that blue,

gold, and rust red “metal gingerbread” detracted attention from the

paintings and that simple clean white columns would be better. Interestingly, the cast-iron pillars might not have been discovered were it not for Hyman’s hunches. Only after the columns were restored were records found indicating their existence. Although their entombment was certainly a public event, people who were alive at the time it happened didn’t record the event in newspapers or magazines, or in any way that would have passed the information on to the next generation. Memory of the event was buried in plaster with them—a harsh commentary on the instability of the community that runs our public institutions. You can be sure—as sure as night follows day—that the interior galleries of that museum will not stay as they are now, restored authentically. If the building endures, changing fashion will again dictate something different. Ornate cast iron fascinates us today because it has become uncommon. In 1890, traditionalists were making the same kind of snide remarks about it as traditionalists do today about plastic and fiberglass. Remember this when you remodel or build your home. Books and magazines will exhort you to hire interior designers and architects to advise you. Some of them know structural principles you need to follow (carpenters and builders know them better), but mostly they will tell you what is in “good taste” today. They will reflect the bias and opinion that pumps vitality into today’s trends. Some 20 years from now, the next generation of trendies will champion other fashions. For example, there is now a sort of mini-trend back to real linoleums to authenticate houses built when linoleum was king of the practical floor coverings. You could argue the pros and cons of linoleum forever. For sure, the kind of mastic they often used in the ‘40s was the eighth wonder of the world, as you know if you have ever tried to take up off the floor old linoleum from that period. It is easier to remove the whole underlayment! The point is, regardless of style or taste, sheet vinyl is lower maintenance than linoleum, if for no other reason than that you don’t have to clean and wax it as often. Listen to your own heart. What you think is beautiful is as worthy of respect as what Frank Lloyd Wright thought was beautiful—especially if you don’t have to spend your spare time cleaning, painting, waxing, polishing, or repairing it. The second consideration about floors and flooring (that also applies to walls, ceilings, etc.) is whether to do the work yourself. Interior work on a house often falls to the homeowner because once in the house, he or she can undertake projects in spare time, substituting “free” labor for cash. As a general rule, amateurs should be able to lay floor-coverings that come in small pieces—tiles—following directions that accompany the tiles and possibly renting equipment from the floor-covering dealer. Sheet coverings—6-, 9-, 12-, and 15-foot rolls of vinyl for example—require a little more savvy (although maybe less equipment). Basically, however, if you can measure accurately you can handle either job. Compare the price of the flooring if you do it and if the dealer’s crew or an independent professional does it. Then consider the fact that the professional’s seams most likely won’t lift or curl as soon as yours will, if at all. Also consider that the professional flooring contractor will make sure the subfloor is smooth and solid as need be so that hammer dimples and other bumps and gouges in the underlayment won’t start showing through the vinyl floorcovering in a year or so, or that ceramic tiles won’t start cracking on the grout lines and popping up. Put a value as you see it on those avoidances of maintenance and subtract that from the price you pay to hire out the installation work. The difference, a subjective one to be sure, might just show you that hiring out the work makes more sense in the long run. Subfloors and Underlayments For low maintenance, the subfloor is as important as the, floor- covering. If you are laying a floor on a basement concrete slab, moisture from below may be a problem—especially if a vapor barrier was not installed under the slab. One way to solve that problem is to apply mastic to the cleaned concrete and then lay down a sheet of plastic vapor barrier. Then nail furring strips through the vapor barrier to the concrete, using hardened concrete nails. At this point, if you want to insulate the floor, which is an excellent idea, cut pieces of ¾-inch or less rigid foam insulation to fit between the furring strips (which are ¾ inch). Overlay strips and foam with another layer of 1/2-inch rigid foam. Then screw the plywood underlayment through the insulation to the furring and you are ready to lay the floorcovering, having in the meantime raised the floor’s insulative value from an R-value of about 1 to one of about 12. On aboveground wood floors, preparation of the subfloor is even more important to the durability of the floorcovering. For ceramic tile and other grouted tiles, the subfloor must be solid—no give in it—or the grout lines might crack and individual tiles work loose. Normally, the joists under the floor will be sound, but of course if they aren't , they must replaced. The plywood subfloor, hopefully 1/8 inch thick, should be re-nailed with ring shank nails wherever any give is apparent. If you are laying heavy slate, consult with a carpenter to make sure the joists are hefty enough to bear the weight. If you are laying new floor over old linoleum or vinyl, the old floorcovering must be thoroughly cleaned of old wax and dirt so the mastic will adhere to it. All loose seams need to be cut back. All bumps need to be sanded smooth, holes or gouges filled with patching compound, and loose nails removed. All these flaws on the floor surface will show through new resilient floorcovering after awhile if not smoothed away. In some in stances, it's wise to add another underlayment of 3 plywood over the old floor if this does not raise the floor too high. Wherever there’s a likelihood that water will be spilled on the floor, like bathroom and entranceway floors, use exterior-grade plywood, good side up. Particleboard, flake board, and wafer board might swell too much in such circumstances and crack the grout. Really quality subfloors under grouted tiles are at least 1¼ inch thick including underlayment, and they are fastened down with ring shank nails every 6 inches on the joists. Allow a narrow crack between plywood panels (1/32 to 1/16 inch) for expansion, especially next to walls. There is a new brick flooring—actually a brick veneer—that needs no special subflooring. This Pee Dee brick veneer is in stalled with “crystals”—sharp ceramic sand—instead of mastic. The crystals and the 1/2-inch brick veneer can be installed without a special subflooring because the crystals allow the brick to float without cracking. A two-ply layer of felt is installed first, then the brick veneer, then the crystals. A final coat of silicone sealer is put over all. The installation is supposed to be easy for homeowners because the bricks can be cut and arranged before being set permanently in place. Ceramic-Tile Floors For low maintenance, ceramic tile is hard to beat both for durability and low maintenance, and today, for the variety of colors, textures, and designs you can choose from. Because of their relatively higher costs, ceramic tiles today are usually limited to bathroom walls and countertops, if used at all. But if you’re willing to spend some more money, install them in floors, too; you’ll get your money’s worth out of them. Ceramic tile may break, or come loose, it never wears out. New techniques in decorating with ceramic tile now give you choices for almost any part of the house, including beautiful pattern tiles for decorator accents. For floors, ceramic tiles carry various “abrasive-resistance ratings,” which guide you as to choice. A moderate traffic area can get by with a rating of 2, for example, but a heavily traveled hall or foyer needs a 3 or better. For bathroom floors, slip-resistant and moisture-proof tiles are needed. Ceramic tiles are baked clay and when baked hot enough, they absorb practically no moisture at all, especially those made from the highest refined clays and fired at temperatures over 2,000°E These are referred to as impervious tile. Fully vitrified tile, the next classification downward, will not absorb more than 3 percent water, which is acceptable for even wet locations. Semivitreous tile absorbs from about 5 to 7 percent water, and nonvitreous tile something more than that. But even nonvitreous can be laid in wet locations if no freezing will occur there, and it should be laid in mortar over a moisture barrier. Ceramic tile may be glazed or unglazed. Unglazed tile is usually of earth tones—the colors of the clay itself—that run all the way through the tile. Glazed tile has a baked-on surface—a glass surface that's smooth and easy to clean. Glazing allows an almost unlimited number of colors and designs in ceramic tile. There are three general kinds of ceramic tile, as discussed below. QUARRY TILES These are unglazed. Their earthy tones, mostly reddish, go all through the tiles. They are formed by extrusion of natural clay or shale through a die and are wire-cut at proper intervals. In size they range from about 3 inches square up to 12 inches square and cost from $2 to $3 a square foot. Other geometric shapes are available. Quarry tiles are stain resistant, but not considered stain-proof. They are very strong, hard, and semivitreous, with a water absorption rate of 5 percent or less. CERAMIC MOSAIC TILES These are what everyone thinks of when ceramic tile is mentioned. Mosaic tiles are rather expensive and so their floor use is limited for most of us. They may be porcelain or natural clay and come in small sizes—as small as ¾ inch square up to 4 inches square. They are almost always arranged on larger pieces of fabric or paper for easy handling. Some are glazed, some unglazed, and the styles designed for floors contain an abrasive additive to make them less slippery. To appreciate the beauty as well as the low maintenance possible with mosaic tile, write for American Olean’s catalog or The Ceramic Tile Manual from the Ceramic Tile Institute. PAVER TILES Paver tiles can be glazed or unglazed, porcelain or natural clay. For the unglazed, the price starts at about $2 a square foot and goes up, considerably, in the porcelain payers. Ceramic pavers are formed in molds and generally have more precise edges and dimensions than quarry tile. Mexican paver tiles, as they are called, aren't precisely sized, but are more or less handmade and quite popular now due to the yen for the “country” look. Often the wet clay is rolled out with a rolling pin right onto a hard clay surface and cut into 12-inch-square pieces with big “cookie cutters.” Left to dry outside in the sun, some actually show tracks of chickens in the finished surface, though I suspect enterprising Mexican artisans encourage their barnyard fowl in this droll caper because it makes the tiles sell better. The tiles are often fired in homemade kilns, some of which ought to receive grand prizes for originality. For example, one “kiln” I’ve heard about was actually an old car body. The inside of the car was loaded with tile and then the car was covered with old tires. The tires were set on fire and the heat of the fire baked the tiles. (I wonder what the EPA would have to say about that.) Mexican payers absorb water readily and should be given a silicone sealer coating. Somewhat cheaper than other ceramic tiles, they are excellent for patios and foyers, but not recommended for bathrooms.

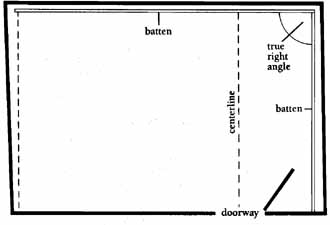

Laying Ceramic Tiles Yourself Instructions come with boxes of tile that tell you exactly how to install them—better information than I can give here because it will bear specifically on the particular kind of tile you have selected. But I can add a few words in general. In laying out lines on the floor to guide you in setting the tile straight and square, remember that no floor is perfectly square. Generally, a center line is drawn from the middle of the doorway perpendicular to it across the floor. All square measurements are then taken from this line. You can mark off a line square to it along adjacent walls. After that, nail a straight batten along two adjacent walls, forming a true right angle just out from the wall. If the battens can be arranged so that the tiles installed inside them come out even, in other words, without cutting, so much the better. The tiles are then laid, the battens removed, and the uneven portions along the walls filled in with the cut tiles. Another way to lay out a floor, especially on a small irregular floor like a bathroom, is simply to make a trial layout of the tiles on the dry floor, making appropriate guide marks on the floor when the tiles are in place. For looks, all square measurements should be taken from the center line down the middle of the doorway, as in the previous method. This is a foolproof way for a beginner, especially if he or she divides the small room into smaller portions, like the space around the toilet, the entryway, the space between vanity and shower, etc. A good square is about the only tool needed for this placement and measurement.

The cut tile should always be up next to the wall where the trim will hide the uneven line. Any “cheating” you need to do to adjust your square lines to the unsquare walls should also be done at the wall where the trim will hide it. Where the tiles form a definite pattern and it takes, say, 17 1/2 inches from one wall to the other, it's a good idea for a balanced look to cut ¼ inch off the tiles along both opposite walls rather than ½ inch off the tiles along just one side. To cut tiles, you need a snap cutter and a nibbler for taking off small bites or especially for cutting curves in a tile. You can rent both from the person who sells you the tiles. An ordinary glass cutter can be used to cut straight lines in place of a snap cutter; score and break the tile as you would a piece of glass. You also need an abrasive stone to smooth off rough cut edges, plus trowels, a straightedge, perhaps a chalk line (in lieu of battens), and a sponge or two. I’ve already mentioned the importance of the mastic and grout, since generally speaking it's these materials that fail, never the ceramic tiles themselves. The really classic way to install ceramic tile is in a bed of mortar 1 inch thick, and it's still the best way for a wet location. Most tiles, however, are being laid in epoxy mastic today, since the new mastics (like Latapoxy 210) are suitable even for bathroom floors and are very easy to apply. They usually come in three containers: an epoxy resin, a hardener, and a blend of cement and sand. These are all mixed together according to the instructions given and applied evenly to the subfloor with a trowel that has notched edges. The notches leave the mastic in little ridges that makes seating the tiles securely an easy task. Once the mastic is spread, the tiles are pressed into it, allowing 1/16 to ½-inch space between for grout joints. (Some brands of tile come with separate spacers to insert between the tiles; other types come with built-in spacers—tabs on the edges of the tiles that are pushed together tightly during installation and then covered with grouting. American Olean is one company that makes tiles with built-in spacers.) If the mastic keeps bulging up in the joints, you have applied too much of it to the floor. Excess mastic must be rooted out of the cracks with a nail or similar tool before it dries. After the mastic dries, apply grout over the tiles, squishing and packing it into the cracks. Many floor contractors add latex to their grout to make it spread easier. They also dampen the tiles first with a sponge for the same reason. Use a rubber trowel or window squeegee to apply the grout. Remove the excess with a wet sponge. Make the grout joints even and slightly indented with an old toothbrush handle or similar tool. Dig out any grout that has gotten down into the expansion joint between subfloor and wall (see “Subfloors and Underlayments” above). Caulk that crack after the floor is finished and dry. Unless directions say otherwise, you should apply a silicone sealer to the grout joints. Your ceramic-tile floor is only as good as its grout. Sources of ceramic tile include American Olean Tile Company; Olympia Floor and Wall Tile; and Elon, Inc., which is an especially good source for imported tiles, including Mexican ones.

Resilient Floorcoverings Innovations in resilient floorcoverings increase almost monthly, with vinyl leading the way. True linoleum, despite its higher maintenance, is enjoying something of a comeback. It is still made by the Krommenie Company in Holland and distributed by the L. D. Brinkman Company. Cork flooring is comfortable to stand on, absorbs sound well, and if you drop a dish on it, you might be lucky and the dish will bounce rather than break. But cork by all standards scores poorly for low maintenance. Rubber and synthetic rubber floorcoverings have their devotees, also. Both are excellent where a nonslip surface is desirable, absorb noises well, and are naturally cushioned. Rubber is resistant to most chemical spills. Synthetic rubbers like Noraplan Duo never need waxing. But it's vinyl that makes most of the headlines these days in the resilient floorcovering world. New methods allow not only a seemingly limitless number of colors and patterns, but also almost perfect mimicry of wood, stone, marble, and other natural materials—you name it. There are two main categories of vinyl sheet flooring and vinyl tiles: inlaid and printed or photogravure. Inlaid flooring is made up of many tiny bits of vinyl compressed together at high temperature. The color goes deeply into the material and can’t wear off. Inlaid vinyls are rather stiff and hard—which is good for low maintenance—but makes them more difficult to install. Photogravure vinyls, as the name indicates, have the patterns printed on them and are then overlaid with a clear layer of vinyl for protection. Most floorcoverings in this category have a layer of cushioning in them. They must be sealed at their seams with a special solvent that glues the two seams together to keep out moisture. Cushioned vinyl will show up deformities in the underlayment quicker than inlaid vinyls will, and although great improvements have been made, many householders still contend that they do not hold up as well as inlaids. Both kinds can be purchased in so-called no-wax finishes. This does not mean no-work, however. After installation, the floor should be washed with hot water and a mild detergent, unless the vinyl carries instructions to the contrary. After that it needs regular mopping. After a few years, the flooring will lose some of its gloss and needs to be buffed occasionally. On some urethane-covered flooring you can restore the gloss with an acrylic floor dressing recommended by the manufacturer—wax won’t set properly on urethane. Dirt will build up on no-wax floors despite mopping, especially if the surface pattern is textured. People who really hate to clean floors should buy flat matte surfaced vinyl. Laying Resilient Tile Floorcoverings Measuring for vinyl, rubber, cork, and other similar tile is done about the same way it's for ceramic tile. Tiles are easier to install than sheet floorcoverings for the amateur. However, from the standpoint of low maintenance, any resilient floorcovering is better in sheet form than in smaller tile pieces. Why? The more seams, the more maintenance. A floor that can be covered with a single piece from a 15-foot roll has no seams to curl up or to catch dirt and moisture. But if an occasional tile does curl or buckle, it's at least easier to repair than sheet floorcovering. Vinyl will soften if heated (don’t heat too much Direct a hair dryer, or heat lamp if you have one, on the curled up edge until the tile softens a bit. Then pry up the edge or corner with a knife or old screwdriver and direct the heat under the tile. Moisture is almost always the culprit and you want to dry the area under the tile completely. Then scrape and vacuum out all the dirt and old adhesive you can. When the underside is clean and thy, apply new adhesive and push the tile back in place. Weight it with something heavy until the adhesive sets. If you have to replace the whole tile, begin by lifting a corner as described. Cut off the corner so you can work a stiff putty knife under the main part of the tile. Get it warm and soft with your hair dryer first. After removal, clean and dry the space under it, spread adhesive, and lay down the new tile. Butt the new tile at one edge up against the adjacent tile and push the tile straight down into place. Don’t try to slide it in place. Spread the adhesive with a notched trowel—or an old saw blade. Use anything with a notched edge that will leave the surface of the adhesive slightly rippled. A bubble or buckle in the tile—and this holds for sheet floorcovering too—either from moisture or a popped nail, should be softened with heat as above. Then cut a slit in it, removing the nail and /or dirt. Dry the area under the slit thoroughly, and push in adhesive. Weight down. Getting a new tile to match your floor is difficult. Even the same design may not match in a new batch of tile. The wildest, but maybe best solution is to get some tiles totally different than those on the floor, replace the bad one and several good ones scattered appropriately around the room and call them, with a very straight face, accent tiles. Laying Resilient Sheet Floorcoverings

Putting down sheet floorcoverings, like laying carpets, is slightly more difficult than laying individual tiles. But if you can measure accurately, you can do it. Armstrong, a leading manufacturer of sheet vinyl and other floorcoverings, is so sure the do-it-yourselfer can lay sheet vinyl that if you use its “Trim and Fit” kit and make a goof while cutting or fitting, retail stores you deal with will replace both the flooring and the kit. While Armstrong was the first to make such an offer, now other flooring manufacturers sell similar kits with the same guarantee. Essentially what you do with any sheet floorcovering is to make a pattern of the floor on felt paper that comes in 3-foot rolls, taping strips together to pattern the whole floor. You cut the felt roughly an inch away from the walls, cabinets, etc. This edge isn't the pattern line. The actual pattern line is traced on the pattern using a square. The blade of the square has to be wide enough to extend from the wall over onto the pattern, and since the conventional square is 1½ inches wide, it will do that. With one side of the square’s blade against the wall, you trace the wall’s outline on the pattern on the other side of the blade, going all around the walls and cabinets and door frames. Every angle, however slight, needs to be re corded on the pattern. Then the pattern is laid over the floorcovering, centered correctly, and the pattern line transferred back onto the floorcovering with the square, reversing the procedure by which you traced it on the pattern. If there must be a seam, cut the flooring so that the design matches on both sides of it. Latex mastic is used to glue down the floorcovering, but epoxy must be used to glue down 3 inches of the flooring on either side of the seams, as per the instructions that come with most resilient vinyls today. After the first piece of flooring is glued in place with mastic, lift the seam edge and spread the epoxy underneath. Then spread another 3 inches of epoxy on the floor where the second strip will butt against the first. Apply the mastic for the rest of the second strip and then lay it down in place. If the second strip does not want to lie down flat at the seam, put a weight on it or tap the two seam edges together until the epoxy sets up. Instructions with your vinyl will cover all this in detail. I am loath to give more detailed directions anyway, because likely as not they will be outdated very soon. A case in point is Armstrong’s new type of vinyl flooring it refers to as “tension flooring.” It is glued only around the edges and then it shrinks tightly onto the floor surface. Some kinds may even be stapled around the edge rather than glued, so that laying vinyl becomes quite similar to laying carpet. Stone and Masonry Floors Stone, especially slate, and masonry are so enduring, fireproof, and beautiful that many homeowners overlook minor disadvantages and are using them not only for foyers but living areas and even kitchens, where a dropped glass is a goner for sure. Some masonry floors do stain easily, but an acrylic or silicone sealer can prevent that problem fairly effectively. Modern scientific testing does not support the common belief that masonry floors don’t “give” and therefore tire feet and legs more quickly, especially in the kitchen where one does so much standing. The National Bureau of Standards maintains after testing that the human body does not weigh enough to cause “give” in any of the so-called resilient floor- coverings: you’ll get just as tired standing on a vinyl or wood floor as on a stone one. In any event, we should, without doubt, give more consideration to stone and masonry for the more traveled floors in our houses. For example, we persist in carpeting stairs where hard-wearing and beautiful marble would soon pay for itself. Marble Floors Marble floors are probably not practical in kitchens or anywhere else where spills are probable. Marble stains a little easier than many other good floorcoverings, if the spill isn't wiped up immediately. Marble does wear a little over the years, but because the color goes all the way through, the wear is hardly noticeable until the second century of use. Marble can be slippery, but marble that’s to be used for floors, stair treads and thresholds is given a honed surface rather than a polished one because it isn't as slippery.

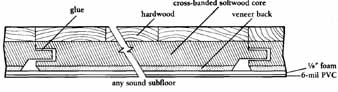

Slate Floors Slate is the stone floorcovering of choice today. Individual slates are laid in thin-set mastic and the grout is applied later just as for ceramic tile. It is imperative to put a coat of silicone or acrylic sealer on the slates to keep them bright and easy to clean. In fact, a smart thing to do is to put sealer on before grouting, being careful not to spread the sealer into the joints. You’ll find that any grout that you accidentally get on the slate will clean up a lot easier if the slate already has sealer on it. Then after the grout had dried, put on a second coat of sealer, being sure to seal the grout as well. After that, a yearly cleaning will do. At home we use Murphy’s oil soap to clean our slate, and we don’t get it done every year, either. After a scrubbing with that soap we apply a slate wax. Then any water or mud that dribbles off winter boots and shoes is easy to wipe up with a mop. Concrete Floors Not quite so well known as real slate, brick, tile, or granite are the new concrete floorcoverings made to look like them. They are laid like slate and though not as durable, they will last a long, long time. Jim Pardue, vice president of sales at Coronado Stone, which makes concrete products of this nature, says that installed, the price of payers that simulate brick, stone, or whatever runs about $8.50 a square foot. He recommends about a 1/2 joint between payers. Each tile is handcrafted at Coronado, and one is hard put to believe they are really concrete when laid into beautiful floors. The tiles come with one coat of acrylic sealer on them and Pardue recommends that the homeowner apply a second coat before or after installation. After that, a periodic mopping with a common kitchen floor wax is all the care necessary. There are designs for every kind of decor and every room. Brick Floors Brick, like other masonry floors, works well in passive solar systems since it will soak up solar heat and give it back as heat throughout the night. At a cost that starts at about $3 a square foot, it's also among the cheapest of the durable, low-maintenance floors. Brick floors should be coated with a sealer, otherwise sulfates from the mortar might form a white powder on the surface. This is true of all masonry floors laid on concrete. A synthetic floor wax serves as a suitable sealer for this purpose. Terrazzo Floors Terrazzo, which is concrete with marble or granite pebbles in it that has been sanded down to a smooth finish, is probably the ultimate floor for low maintenance. It needs to be sealed or waxed, but there should never be any repair work required, barring an earthquake. Wood Floors We, of a woodland culture, speak lovingly of the “warmth” that a wood floor (or a wood anything) casts onto a house interior. This is mostly sales hype. We now have vinyl floors that so faithfully imitate wood grain and even come in narrow strips the same shape as wood floorboards, that any difference in “warmth” is entirely imaginary. Wood floors are basically high maintenance and only because of the new finishes that add a protective coating to them do they merit inclusion in this book. Moisture is the bugaboo of wood, and I do not mean the occasional spills of water all floors are subjected to—or at least I mean those spills least of all. Rather, it's the swing from high humidity in summer to low humidity in winter (which will be discussed in more detail in section 13) that can be the biggest problem. White oak, hard maple, mesquite, and ironwood are floor woods so hard they will wear forever and then you can sand them down and they will wear forever again. But alternate moisture and dryness will swell and shrink them as easily as any other wood, and cupping and crowning (bulging upward) can occur. Thus, the wood should be treated with a varnish or sealant that makes it more or less impervious to the entrance of moisture. Often hardwood floors are sealed on the upper surface, but that doesn’t do much for moisture coming from below. Especially in new housing, it's unwise to lay raw wood floors down where concrete or plaster has not thoroughly dried, or after the wood has been exposed to humid weather. The fact that the hardwood floorboards have been kiln-dried makes no difference. Raw kiln-dried wood readily absorbs moisture on humid days and swells. If nailed down on a concrete or plaster subflooring that isn't completely dry, the boards may cup. Then you need to sand them down flat. Then, after the house dries out and is heated up its first winter, the floorboards shrink and pull down at the joints, causing the boards to crown, necessitating another sanding and refinishing. The safest and generally more expensive route (up to about $10 per square foot) is to buy prefinished hardwood floorboards, or have the bundles of boards stored at normal house heat and humidity for a month or so before installation. The latter course is much more easily accomplished in remodeling than when building new. For both unfinished and prefinished hardwood flooring, one good source of many is Harris-Tarkett, Inc. The great thing about wood is its versatility. You can sand it to renew it or to give it a different finish. New methods allow white oak to be bleached to an almost white floor, stunning even if it does show dirt more. Red oak is used a lot today for floors, although it isn't nearly as hard and long lasting as white oak, and don’t let anyone tell you it's . But red oak still will last a long time and can be stained to look much like cherry or mahogany. If you have money to spend, you can invest in exotic wood floors—rosewood or ebony even. Or use these woods sparingly in mosaic designs with cheaper maple or with ceramic tile. If you really love wood, you can install wood that makes for a practical kitchen or even bathroom floor because the boards have been treated, impregnated actually, with polyurethane plastics, and are just as “no- wax” and impervious to moisture as the vinyls. Or so the advertisers say. I tend to agree with Paul Hanke, writing in New England Architect and Builder Illustrated: “Wood flooring. . . is subject to wear and tear particularly since the finish (urethane or oil and wax) is surface-applied and must be regularly renewed. . . Water is taboo for wood floors and they are a poor choice for areas where sinks, tubs, or washers may overflow.” Wood floors come in planks, generally 4, 6, or 8 inches wide or in narrower strips or in various block designs generally referred to as parquet. Planks are usually nailed down, the nail holes filled with wood plugs that become part of the floor’s design. Or the nails are driven in at the leading edge of the boards, below the surface where they don’t show. The narrow strips, perhaps the most popular hardwood flooring, are narrow to reduce the possibility of warpage, which increases with the width of the board. Both plank and strip are usually tongue and groove today. Parquet floors may be nailed to the underlayment, but they are usually glued. There is now a new way to install wood flooring developed in Europe. Whether strip, plank, or parquet, the flooring is laid down on several crossed layers of subfloor and isn't glued or nailed. This “floating” system is easier for do-it-yourselfers than conventional methods and allows you to take the floor with you when you move. Harris-Tarkett sells special underlayments for this kind of floating floor installation, plus other installation tools and materials. Local lumberyards that carry wood flooring should also be prepared by now to advise you about this method of installation. You can use it right over old vinyl or carpeting if you wish. It’s more expensive in terms of materials, but less expensive in terms of labor.

Sanding an old wood floor back to the look of a new one is a mess of a job, but because we treasure our wood, it will add value to your home more than carpeting or the best vinyl would. Rent both a big floor sander and an edger. Don’t try to do the job with a little carpenter’s belt sander. Sand with the grain mostly, but if the floor is badly cupped or rough, sand first at an angle slightly biased to the grain and then sand with the grain. Use a rough sandpaper first, then a medium to fine grit. Wear a respirator. When you are finished, wait a few days for the dust to settle and then clean up. The main trick to sanding with a power floor sander isn't to let the thing stand in one spot while it’s running or it will quickly gouge a rut in the floor.

The best finishes or sealers for low-maintenance wood floors may not be the best for the wood. Shellac and wax give a soft, mellow, beautiful finish that allows the wood to “breathe,” but you will have to wax often to keep it looking good. Urethane varnishes provide the toughest surface, so tough in fact that they may chip rather than flex like a phenolic varnish. The latter is usually recommended where foot traffic is heavy as in the kitchen or foyer. Gymseal is one of many phenolics recommended for floors.) So-called alkyd varnishes like Fabulon’s Acrylic Wood Finish, available at most hardware stores, are also recommended in this situation. But the hard polyurethanes are difficult to beat for low maintenance. Any good paint and varnish dealer would love to educate you in detail on this subject. Even more low maintenance can be obtained with penetrating sealers, often incorporating polymerized tung oil. There are many brands. Before you sand and refinish, consider simply cleaning the old wood floor with a mild paint remover—de-glossers as they are called. This can be especially effective in an old country house where you wish to preserve a feeling of yesterday. The patina of the old cleaned wood might be more appropriate than a newly sanded, glossy surface. If a few spots don’t come very clean or still show old stains, plop area throw rugs over them. Now that’s low maintenance. Carpeting and Rugs Homeowners shopping for a new carpet think mostly about color. Like the kings of ancient Assyria in the Fertile Crescent of Mesopotamia who treasured new and rare blue and purple dyes in wool as much as they did gold and silver, so we all, being human, are moved by new and /or unusual colors. Also the rug must, by heaven, match the room’s decor. Unfortunately, this attention to color does not always serve durability and low maintenance. For example, technology has now found ways to treat nylon fibers so they resist soiling and staining to an amazing degree, opening the way to an almost unlimited range of new light rug colors. Pastels, once unheard of for a rug, are now fashionable and stunning, to say the least, after years of dark-colored carpets. The fashion, from a low- maintenance point of view is somewhat self-defeating, however. Because of their lighter hues, the new rugs show dirt more even if they do clean up easily. So to keep them looking their best they have to be cleaned more often. Smart is the homeowner who takes advantage of the best of both worlds: buys the dirt-resisting nylons to be sure, but in richer hues like wine burgundy, pine green, or cordovan brown. These colors will show light-colored hair, threads, and bits of paper and dirt more readily—all of which can be vacuumed easily—but won’t show the more persistent dirt and stains so fast. Of the four major kinds of interior rugs—wool, nylon, polyester, and acrylic—wool remains the most durable and , all things considered, the best choice for low maintenance. Yet wool is the most expensive. A good one will cost around $45 a square yard and up, mostly up, so people turn to synthetics that provide a fairly good rug for half the cost of wool. Wool is naturally nonabsorbent and so somewhat stain- and dirt-resistant; it's very slow to burn and is quite fire resistant. It also resists crushing of the pile better than any other rug material. Wool will fade or deteriorate in direct sunlight, but so will nylon and polyester. Wool is subject to insect attack— clothing moths—but all good wool carpeting comes factory-treated against this danger. Wool rugs are so durable in fact that hand-woven types have become collector’s items. Oriental rugs actually increase in value with use—”the surface patinates and the colors mellow” is the phrase to use if you want to impress your friends. I’m told that the airport terminal at Cairo is carpeted with Oriental rugs over which millions of feet have trod, just to show the world how well a really good wool rug will wear. Collecting Oriental rugs became a fad in the ‘70s until the price rose and there was little money to be made by new investors. Prices peaked, at least for the time, about 1980. But you can use the rugs maybe until the next round of price increases and they will still be in very good shape and still valuable. Value of course varies. The really priceless Oriental rugs in museums have as many as 2,000 knots per inch, which is almost unbelievable. Even 500 knots per inch makes an extremely valuable rug, and 150 to 200 quite acceptable in some designs and shapes. The Navajo rug is an extremely durable type that has become so sought after by collectors that it's too expensive for practical floor coverings. Normal sizes today are too small for floors except for throw rugs and are used principally as wall hangings. But you can use them on the floor and be assured that normal use won’t harm them much in a lifetime. The Wall Street Journal recently said that next to real estate, Navajo rugs are the best investment you can make. Rugs measuring 3 by 4 feet were selling from $550 to $1500 in early 2006, and one about 4-by-8 feet went for $1,400, all of which would resell in Santa Fe for probably twice that. Average prices have tripled since the early ‘60s. The irony of this situation is that farmers get very little for their wool, and Navajo weavers, except in some cases, hardly make minimum wages. Of the three principal synthetics, nylon is the best for low maintenance and generally costs more than polyester or acrylic. All three are fire resistant but will melt or scar from a hot cigarette or an ember popping out of the fireplace. Nylon and acrylic resist crushing better than polyester, but polyester is slightly more resistant to abrasion. Acrylic does not fade in direct sunlight as much as nylon or polyester and is a good choice under a picture window that faces a southerly direction. The synthetics are all immune to insect damage. Polyester is usually factory treated against mildew, a problem sometimes. Polyester and acrylic create less static electricity than wool or nylon, although nylon manufacturers are experimenting with metal threads in their carpets that seem to cut down on this annoyance. New rugs, of whatever kind, generate more static than ones that have been around for a while. Static is also worse in winter, when heating the house dries out the air. Whatever kind of rug you choose, the best key to its real value is its density. The more fibers or strands packed into a given space, the better. Bend a portion of a rug back and if you see lots of backing, the rug is obviously not very dense and should be cheap. A good place for a cheap rug is the spare bedroom, used only when Aunt Hildy comes to visit. Pile rugs are composed of many loops of fabric woven into a backing usually of jute or polypropylene, the backing coated with a layer of latex and then another backing added. Such rugs are called “tufted” rugs. If the rug consists of warp and woof fibers woven together, it's a woven rug, made on a loom. Tufted rugs are easier and faster to make by machine and so are generally cheaper. You can usually identify them by looking at the backing. The directions of the weave on the back will have no relationship to the directions of the weave on the front. Tufted rugs won’t unravel at the edges if you need to cut them. Woven rugs will if the edges aren’t bound. The bound edge is called a selvage, and if you see on a carpet edge the telltale zigzag- or diamond-shaped binding, you’ll know you are looking at a woven rug. The looped strands that form the pile can be cut on the surface to make each loop into two separate strands. This is then called a cut-pile carpet. It creates a shearer, smoother, plusher surface than the loops, but it isn't as durable or crush resistant. So-called sculptured rugs are com posed of uncut loops at different heights. There are other variations in the twist of the fibers or in heat treatments during manufacturing that may increase sturdiness or density. These processes make different textures, but add or detract little in the way of low maintenance. In weekly vacuuming, carpets will come cleaner and therefore last longer if you use a vacuum that has a beater as well as a sucking action. If you move the vacuum slowly over the rug, it obviously will get more dirt out. Don’t be in a hurry. Blot up spills immediately, and if staining occurs, use a spot remover according to directions. Those people who are always rearranging their furniture may not be as crazy as the rest of us think they are. This is a very good way to get even wear out of your carpet and hence longer life. A good carpet deserves a good pad under it. Even a cheaper carpet deserves a good pad under it because that more than anything else will contribute to long life. Generally speaking, the thicker the rug the thinner the pad need be, but rely on your dealer for the proper advice. You can install a carpet yourself, but most carpet dealers will include installation with the purchase price. It seldom pays to do it yourself and botch the job.

Indoor-outdoor carpeting is a synthetic called olefin, or sometimes polypropylene olefin. It is very durable and the least expensive of all the carpeting, which proves that price and durability aren't always connected. Olefin is the carpeting to use for outside steps or porch, basement, bath or kitchen, if you insist on carpeting such areas. Low maintenance would dictate otherwise, however. No matter how inured olefin might be to water and other liquids, cleaning up spills is more difficult than from vinyl or other hard floors. Why do it? I have seen kitchen carpeting that almost reeked with the residue of spills. This may be the fault of the homeowner, not the carpet, but I still ask, why? If you like to stand on something soft at the sink, why not an attractive rag throw rug that you can put in the washing machine when it gets dirty? As for carpeting on walks, entryways, and porch steps, a year or so of weathering makes it look so shoddy and artificial that I think it detracts from the appearance of the house. Masonry is much, much better. Braided and rag rugs from scraps are very durable since they usually are made of wool and /or denim. Such throw rugs can be a real bargain at garage sales. Don’t try to get dust and dirt out of a woven or braided throw rug by snapping it in the air, because you can easily loosen the weave that way. Hang it on a clothesline and beat it the old-fashioned way. That’s not particularly good for the rug, either, but safer than snapping it. Beating does not wear (and certainly does not fade) a rug as much as laundering does.

|

| HOME | Prev: Landscape Walls and Walks | Next: |