Sewing relaxes me. Buying a sewing machine doesn’t.

I spend a lot of time testing new and used sewing-machine models and hanging out in sewing-machine shops talking to the salespeople, owners, and technicians.

While doing this, I’ve watched many a customer come

in to a shop and agonize over whether or not she should buy a sewing

machine and which machine it should be. Was she making a mistake? Was

she getting a good deal?

Why, I’ve wondered, are we so uptight about buying a machine when sewing itself is such a relaxing pastime?

And then it hit me: It’s like buying a car. Once you drive it out of

the showroom, it’s yours. It’s like using a computer. The silly, little

appliance you are trying to boss around seems to know more than you

do, It’s like selecting a musical instrument.

The right one will help

you to express your creativity; the wrong one will just frustrate you.

It’s like getting married. You always wonder how your life would have

been different if you had selected the other model.

Choosing and buying a sewing machine is complicated because it involves spending big money, dealing with new technology, knowing the limits of your creativity, and understanding your own ego.

I understand because I’ve been there.

A Sad Sewing Story with a Happy Ending

I once fell in love with a sewing machine that I had to have. I saved up my dollars to buy it, and when they totaled $2,300, I bought it. (The asking price was $2,900. See later section on bargaining techniques.) I took it home and found myself immediately disappointed and depressed with my purchase. Yes, I had studied all the models. Yes, I wanted that machine. Yes, it was a well-deserved birthday present to myself. So why was I so unhappy?

When I think about that purchase, I now realize that I was caught in a conflict between my head and my heart. I wanted that machine. After all, didn’t I deserve a great present for my birthday? Yet I felt guilty spending that kind of money. Since I couldn’t live with the conflicting emotions, I asked the dealer to take the machine back. He wouldn’t. So, I placed an ad in the paper and sold it for $300 less than I paid.

The moral of the story is a $300 mistake is cheaper than a $2,300 mistake.

I don’t regret selling that machine. I would have never been happy with it. (A few weeks later at a garage sale, I bought a wonderful Bernina 310 for $10 and spent a most satisfying week making it purr again.)

If decisions like spending several thousand dollars for a sewing machine are difficult for you to make, or if you are like me and you sometimes make decisions now only to regret them later, you may want to think about how you make decisions in the first place.

THE STRATEGY OF CHOOSING

Whenever I am faced with a difficult sewing-machine buying decision, I ask myself three crucial questions:

• Can I really afford this purchase?

• Do I need, want, or deserve this machine?

• Are my head and my heart together in this decision?

Let me give you some strategies for answering each.

Can I afford this purchase?

Since a sewing machine isn't usually returnable to the dealer for a refund, it's important to ask this question concerning your hard- earned money up front: Can I afford to buy a new machine?

If you come to the conclusion that you really can’t afford to buy a sewing machine at this time, don’t despair. In a later section I give you 10 creative ways to find the “hidden” money in your life. If you can’t save the money on your own, your sewing-machine dealer might have a payment plan to help you out.

Do I need, want, or deserve this machine?

In my favorite kitchenware shop, I stood in front of a wonderful electric ice cream maker that makes a quart of ice cream in a half hour. Just add the ingredients, push the button, and wait. It costs $499. Oh yes, I wanted it. I wanted it badly. I’d even promised myself that I would only make low-calorie sherbets with it, not those delicious, creamy, custard- based ice creams with names like espresso-cream-nut-swirl——yes!—— with a dab of chantilly and a cherry on top.

It’s at delicate moments like this that I ask myself some important questions: Is this something I really need or is it something I really want? And finally, do I deserve this?

Is there any question in your mind that I wanted that ice cream machine? There wasn’t in mine. So why didn’t I buy it? When I thought about what that ice cream would do to my arteries and my waistline, I knew beyond any doubt that I didn’t need that machine.

Did I deserve this machine? This is the hard part. For better or for worse, “deserve” for me is connected to “What have you done lately?” If I finish this guide on time, I deserve a treat. If I lose 30 pounds, I deserve X. If I get good grades, I deserve Y. Well, that’s how I motivate myself. How about you?

I didn’t buy that ice cream maker because after thinking about it for a long while, I hadn’t really done anything special lately to override the negative “need” vote.

So what about this sewing machine you want so much that you dream about it? Do you really need it? Did you do anything special lately to deserve it?

On a scrap of paper, write down some sentences about why you want, need, and deserve a sewing machine. Then, if possible, put these statements in your desk drawer for a day or two and relax. When you reread them, do your statements show you a clear decision-making path?

The chart below gives some examples to help you. You may find the same example in more than one category, but that’s because a “want” for me may be a “need” for you. Don’t worry about that; just do the exercise.

Want, Need, Deserve

Want |

Need |

Deserve |

• I want what Jane has. • I want to do embroidery. • I want a high-quality machine. • I want a machine that will allow me to experiment. • I want all the attachments. • I want a machine that has a lot of fancy stitches. • I want a machine that sews sideways. • I want an industrial machine. • Your statement: |

• I need a machine that can do heavy-duty work. • I need a machine that will last 20 years. • I need a machine that sews leather. • I need a machine that can memorize and repeat a sewing task. • I need a machine to mend clothes. • I need a machine that's easy to carry around. • Your statement: |

• I deserve a new toy for reaching my personal (financial, health, business) goals. • I deserve a reward for saving money by making my own clothes. • I deserve a machine that will respond to my creative needs. • I deserve a machine equal to the value of my husband’s golf clubs. • Your statement: |

Some Head and Heart Responses

Buy a machine? |

Head response |

Heart response |

yes |

• This machine will pay for itself. • I’ve saved up a long time for this; it's time to buy. • I’m going to use this for a special project. • Your statement: |

• I deserve this treat. • I’ve always wanted a fine new machine. • I love the way this machine looks and feels. I just want it. • Your statement: |

no |

• This is too rich for my budget. • My old machine works just fine. • I don’t have enough information to make a good decision yet. • Your statement: |

• I’m afraid I’ll make a mistake and get stuck with something I don’t like. • I feel guilty spending so much money on myself. • I love the machine I have now. • Your statement: |

Are my head and my heart together in this decision?

When you think about buying something for yourself, does your mind tell you one thing and your heart another? This happens to all of us as we internally “discuss” the pros and cons of making any purchase. Here is a non-sewing example to illustrate the point: For years the graduate students in my international management course have asked my advice on what language they should study.

Oftentimes, I can plainly see that they are caught between the conflicting messages they are receiving from their heads and from their hearts. “I should study Spanish because I know that will help me the most. But I’m not sure.” When I ask the students what their hearts are telling them, they may choose German because they remember eating delicious kuchen at their German grandma’s house.

Write down some head statements and some heart statements about buying a sewing machine. The chart above gives some statements to get you started, but be sure to add your own. Again, put them away for a few days and go back to them with fresh eyes.

What is your tendency? Do you always seem to make decisions based on what your heart tells you only to wind up paying too much for something that doesn’t work right? Or do you always seem to make decisions based on what your head tells you only to have something that works right but doesn’t really make you happy?

If most of your thoughts and statements about buying a sewing machine fall into the “yes” part or the “no” part of the chart, you have a clear basis on which to make a decision, If, on the other hand, you are like me, you will find that some of your statements fall into seemingly contradictory categories. This is normal.

My friends who study Zen wonder why I am so determined to separate the head and the heart; they tell me that I am talking about one and the same thing! Perhaps the real trick is to balance the two. No matter, I now know beyond a doubt that making a decision with my heart isn’t going to make me happy if I ignore what my head tells me.

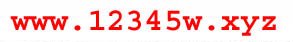

DECIDING TO BUY A SEWING MACHINE

Even though the marketplace is getting more complicated, making a decision about whether or not to buy a sewing machine and what kind to buy need not be a life- arresting dilemma. In the chart on the facing page, I’ve turned the process into a little stroll along a path. All you have to do is answer a question every time you come to a fork in the path. “Yes” will take you in one direction, and “no” will take you in the other. Start in the upper left corner of the path. If you find the question difficult to answer, see below (or following sections) for a discussion of that topic.

If you’ve decided to keep the machine you already have, I’m going to tell you how to take care of it and even how to modernize it for greater sewing convenience.

If you’ve decided to keep your machine and buy another one, you should read the section on how to put your old machine in good order and the section on how to buy another (new or used) machine.

If you’ve decided to buy a used machine, I have some great pointers and some suggestions on what models to look for.

And if you’ve decided to buy a new machine, I’m going to tell you how to buy the right one at the right price.

But first, a few words on sewing machines in general.

Should You Buy a Sewing Machine?

Household embroidery

This machine does only embroidery and is meant to be a companion to your regular household machine. Some people like this two-machine strategy, as it allows them to sew on one machine while the embroidery machine is running, often for longer than 15 minutes.

This mid-range Bernette made for Bernina, called the Deco

500, is a household embroidery machine dedicated to hooped embroidery.

After you insert a design card, you touch the screen to make your

choice.

Light commercial

This mechanical machine is designed for multipurpose, heavy-duty use, for instance, in a tailor’s shop or at a dry cleaner. There are very few of them on the market. Some home sewers like this machine because it offers some of the versatility of the home machine, but it also sews at greater speeds and is more substantial than a household machine.

Industrial machines

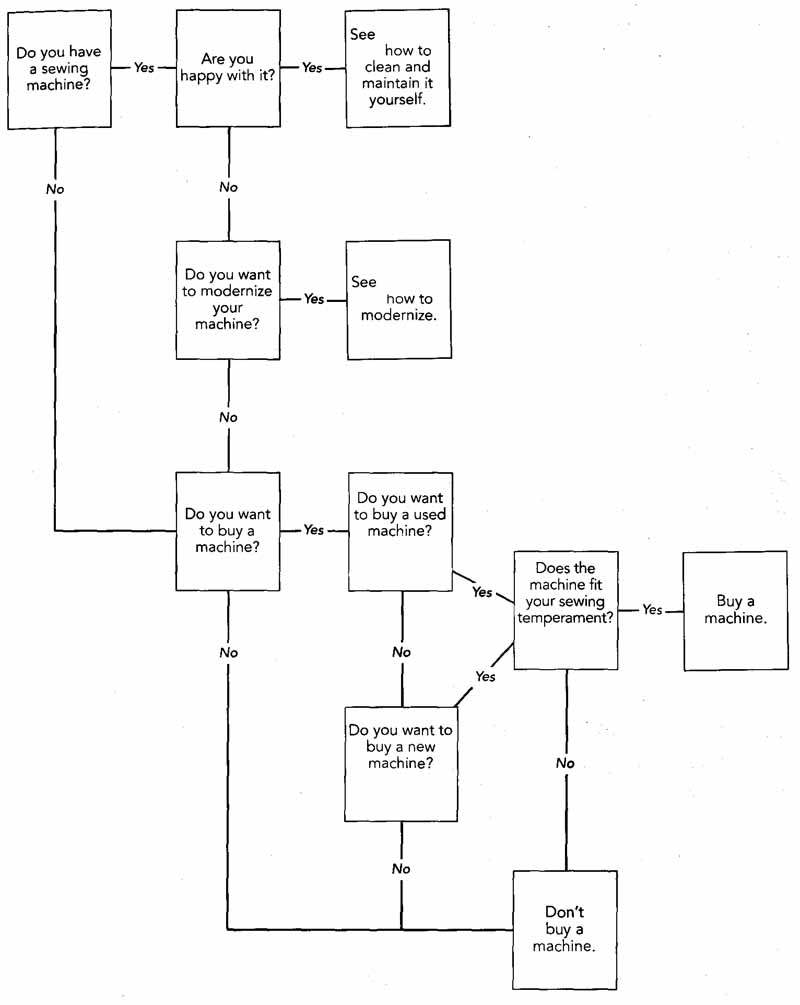

This machine is designed for task- specific (buttonholes, chain stitch, or leather), repetitive sewing at very high speeds. Most machines of this type are still purely mechanical all-metal workhorses, but new machines now come with computerized counters and other features like stitch memory that makes repetitive sewing almost automatic. Modern industrial machines can remember and repeat a specific pattern of sewing, like the number of stitches it takes to sew a pocket onto a shirt. The operator simply turns the fabric when the machine stops and automatically lifts the presser foot. These heavy machines are set in special tables and are linked by a belt to a separate, high-speed motor. Some home sewers like their speed, quality of stitch, and smooth, uncomplicated operating features. See the sidebar on the facing page to see if you should buy an industrial machine.

Industrial machines like this Bernina 217 N (shown at

right) are set into heavy-duty tables under which Sits the large,

powerful motor. The machine on the left is a light commercial Bernina

950, which also fits into a table like the one shown.

Commercial embroidery

Usually attached to a computer, this is the multithread, multi-needle machine you see in shopping malls that embroiders names on baseball hats, T-shirts, and towels. Some entrepreneurial sewers have purchased these costly machines and started small home businesses.

Household serger

Popular in the last 10 years, this is the machine that cuts and sews an overlock stitch at the same time. Like the household sewing machine, it's a multipurpose machine that offers chain stitching; two-, three-, four-, or five-stitch overlocking; and cover stitching. Sewers like the speed with which they can simultaneously cut and bind fabric with this machine. A serger can be a companion to a sewing machine but can't replace it. See the chart and discussion below for a comparison of the two.

Industrial serger

This heavy-duty machine is designed to serge day in ad day out. Like the industrial sewing machine, it's set into its own table and is connected by a belt to a high-speed motor. If you assemble a lot of knits, this may be the machine for you.

TYPES OF HOUSEHOLD SEWING MACHINES

Although the market is changing slightly — sales of industrial machines to home sewers is increasing — it's nonetheless true that most sewers buy household models, It used to be that the only difference between sewing machines was the color.. .and they were all black. Until recently, there wasn’t a significant difference in what sewing machines could do: a zigzag stitch was a zigzag stitch was a zigzag stitch. Mostly what you shopped for was quality of stitching and ease of use.

Quality and ease of use are still important today, but there are many more variables for the sewer to consider. You can still buy a basic machine, but you can also buy one that does everything but scrub the kitchen sink. Here’s some information on the variations of household machines available on the market today.

Should You Buy an Industrial Machine?

There are a few industrial or commercial machines on the market that might interest you if you are willing to sacrifice variety and versatility for speed and accuracy. Basically what I am talking about is sewing on a machine like Grandma’s old, black, straight-stitch Singer…only it’s on steroids!

What you do get is beautiful straight stitching (and a few cases zigzag capability as well) and astounding sewing speed. Sewing accuracy is improved by a few important characteristics of these industrial monsters: They are always flatbed machines set into a large table so you have plenty of support for your sewing project. And the speed itself allows you to sew more accurately since you don’t have time to wiggle the fabric around as when the poky house hold machine makes its stitches. The feet on industrial machines are well made to stand constant use, and they don’t jiggle as snap-on feet often do. The result is more accurate feeding of the fabric and more accurate sewing.

The bad news is that industrial machines don't come with the built- in fun that the top-of- the-line household machines do; they are designed for no- nonsense, task-oriented business applications. You can’t switch stitches at the touch of a button, you won’t find dozens of decorative stitch choices, and you won’t be able to automatically sew buttonholes.

The bobbin on an industrial machine is actually smaller than on some household machines. The machine is very heavy and not portable. It requires its own special table, which is usually, but not necessarily, sold with the machine, and you need to leave the table in one place. The motor is under the table and attached to the machine by a belt, just like the old treadle machine. If you choose the clutch motor, it runs constantly when you turn the machine on, even if you aren’t sewing. A standard motor, which is quiet until you step on the “gas,” is better for home sewers, but the good ones are more expensive than the clutch type. If you mostly construct clothing and do very little machine embellishment or if you have plenty of room in your studio for more than one machine, an industrial model might become your main machine, leaving embellishment and buttonholes to its domestic sister. Visit your industrial machine dealer and test the industrial type the way you would any other sewing machine.

Sewing Machines vs. Sergers

Sewing machine |

Serger (overlock machine) |

Very easy to thread and to choose various stitches. Easy to use. |

Very difficult to thread and to change from one stitch to another. Once threaded or converted, it's easy to use. |

Easily sews in the middle of fabric as well as on the edges. |

Sews mostly on the edges of fabric. Chain stitch and cover stitch are possible in the middle of fabric, but you must convert the machine to do this. |

Needle can be fixed (for straight stitch) or move sideways depending on the pattern selected. Feed dogs move the fabric forward, backward, and , on newer, top-of-the-line machines, sideways. |

Needles are in fixed positions. Feed dogs move the fabric forward only. On some models, two sets of feed dogs, which are independently set, control the movement of the fabric—this is called differential feed, If one is set slower than the other, you can create ruffles or reduce puckering in some fabrics. |

Top thread and bobbin thread produce a stitch. The stitches lock. You have to rip out the stitches to undo. |

Three to five threads produce a non-locking stitch (something like crochet or knitting), which can unravel if you pull on the right thread. |

Cannot cut fabric. |

Can cut fabric while it overlocks an edge — one of the serger’s strong points. |

Modest thread use with straight stitch. Narrow range of decorative threads determined by eye of needle. |

Uses lots of thread. Wide range of threads are possible in loopers that have larger eyes than needles. |

Bobbin thread must be replaced often. |

There is no bobbin thread. Large cones of thread last a long time. |

Sews up to 900 stitches per minute. |

Sews very fast—up to 1,700 stitches per minute. |

Should You Buy a Serger?

Many books have been written to introduce sergers to the home sewer, mostly to answer the questions: What is it? What does it do? Do I need one?

Here’s my short version of this guide: Your sweat suit was serged. The pocket on your blouse was sewn.

Compare the stitches. A sewing machine and a serger are like a hammer and a screwdriver. Both are tools, but both do very different things (see the chart above).

Strictly speaking, all of your sewing can be done on a regular sewing machine. But just as machine sewing is less time-consuming than hand sewing, sergers make many sewing tasks much easier for the busy sewer. These tasks include cutting and binding edges at the same time, making rolled hems on sheer fabrics, and joining stretch knits.

In my opinion, a serger is useful after you learn how to sew well. Entirely serged garments have the same cache as sweat suits, but a well-sewn garment can benefit from a serger finished seam.

If you can afford only one, buy a sewing machine. If you can afford both, think about buying them at the same time to get a good price.

Household sergers can be simple or complex. The computerized,

high-end Elna 925 (left) has it all, while the simpler Bernette FunLock

006D does the basics.

Mechanical machines

Today, the very earliest sewing machines seem like toys to us, since they were so tiny and simply constructed. You turned a wheel with your right hand and guided the fabric through the machine with your left—I have a child’s Singer that works just like that. And in parts of the world where there is no electricity, that’s the way it's still done. Imagine how excited people became when they discovered that foot power could run a treadle machine and free both hands. Eventually, a small motor replaced foot power, but the machine remained basically the same. In the 1950s, mechanical machines became as complicated as Swiss clocks and were made of just as many (thousands of) parts. The machines could sew zigzag and straight stitches, and with the use of built-in or inserted cams they could produce decorative motifs as well. Some of these beautiful machines are still being made today, but they are a fast-dying breed because they are too costly to manufacture and don’t meet the more sophisticated expectations of today’s computer- savvy sewer.

I bought each of these for less than $10 at secondhand

stores. The flatbed Brother shown in the back has dual voltage. The

Bernina 717 (left) came with an extension table. The New Home machine

(right) cost $5 because its accessory box was missing.

When you sew on this lightweight, quiet electronic Elna

Carina, the needle always stops out of the fabric. The black disks

shown at left are the cams you insert to sew various decorative and utility stitches.

Electronic machines

In the 1970s, electronic circuit boards were added to the electric systems of sewing machines that would send maximum power to the motor at any speed—a great and useful innovation. When you are sewing jeans, for example, you may want to sew slowly, but you also want maximum needle-penetrating power. This is impossible on a purely mechanical machine because the harder you step on the pedal, the more power you send to the motor and the faster it sews. If, however, you step lightly on the pedal, you send less power to the motor and that’s when you get into trouble on thick fabrics.

Electronics also allows the needle to always stop up or down (in or out of the fabric), and sometimes you can choose. Some machines even have an electronic eye that “reads” the plastic bobbin to tell you when thread is getting low. Nonetheless, the machine remains basically the same sewing instrument as the mechanical model, especially concerning stitch selection. The machines still depend on internal or user-inserted cams to be “read” by a mechanical finger to produce various patterns.

Computerized machines A sewing machine containing a computer chip doesn’t depend on a cam to give you a pattern. A pattern is written into the brain of the machine by a computer programmer. All you need to do is call up the pattern, usually by dialing its address. For example, you push the “2” button and the “4” button to get stitch recipe number 24. A computer can also remember the things you tell it to do and repeat those things on command.

Imagine sewing one buttonhole and telling your sewing machine to remember what you’ve just done. Now tell your machine to repeat that buttonhole automatically, over and over again. Yes, this is possible with a computerized machine.

This mid-range Bernina Virtuosa 160 has a computer on board.

Push a button and the machine automatically sets the appropriate length and width for the stitch selected.

Mechanical parts that were once linked with belts and gears can now be run by separate computer-responsive motors. When you push a pattern button (or touch the screen itself on some models) on a computerized machine, the brain coordinates the needle position with the hook, the feed dog, and , in some machines, the tension mechanism.

Even in less expensive computerized sewing machines, the stitch library will be surprisingly extensive and built in. In the more expensive models, you can add to your stitch library by buying more patterns that come on credit-card-sized computer cards that you slide into the machine. It’s just like buying software programs for your computer.

If you like the idea of creating your own stitches but don’t have a computer or a computer-connectable sewing machine, Bernina or Pfaff may have a computerized machine to suit you.

A small device called the Creative Designer attaches to a Pfaff 7670 or7570 model to let you draw and enter into the sewing machine any 9mm stitch you want. The Bernina model 1630 has a built-in track ball that lets you draw a pattern on the screen of the sewing machine. The machine then sews the pattern at your choice of five different widths.

On both machines, creating stitches is something easy and fun to do. Because they require fewer parts, are easier to manufacture, and offer the sewer greater options and ease of use, computerized machines have started to replace mechanical ones.

In a few years, the mechanical sewing machine will take its place next to the black-and-white TV.

A Word about Hardware, Software, and Interface

Don’t be intimidated by computer language when you go to look at a computerized sewing machine; it’s really not all that complicated. Hardware is the sewing machine itself it’s what you feel when you pick it up and what breaks when you drop it. Hardware is the motor and parts that make the needle go up and down to make stitches.

Software is the invisible-to-you, automatic instruction given to the sewing machine to do the work. For example, the software tells the hardware (the needle) to move in a certain way to make a certain stitch. And software is what tells the machine how to embroider a bunch of cherries on your favorite dress. A good sewing machine must have both good hardware and good software to function properly. A weak motor, badly configured metal or plastic parts, and poor engineering will not give you good stitches or make sewing enjoyable.

Usually the more expensive the machine, the better the hardware inside. An expensive, well-made machine filled with inaccurate computer instructions isn't any good either. It is the computer that tells the needle where and when to sew, so sloppy computer instructions are not a sewer’s friend. I have worked on computerized sewing machines that do some strange and aggravating things, and there was no way to change the machine’s behavior until the manufacturer upgraded the memory chip. It’s a good idea not to run out and buy a newly introduced model in order to give the manufacturer time to work the bugs out. The good news for American sewers is that the bugs are often discovered in the home market, such as Switzerland, Germany, Japan, or Sweden, so the machines are relatively reliable when they get here.

Interface was a sewing word long before it was a computer word. Interface is something that you put between two things that connects them. In sewing, it’s a layer of fabric between two other layers, and in the computer world, it's what allows you to communicate in plain English to a computer that only understands the language of zeros and ones.

But we don’t have to talk about computers to understand the importance of interface. Even a TV from the 1950s had it: Where were the dials placed? Were the numbers and labels easy to read? Were the controls arranged in a logical order? Interface is the connection between you and the machine. Even if the machine has good hardware and good software, it should also be friendly to use—easy for you and the machine to “talk” to each other. Unclear instructions, poorly placed buttons and levers, and complicated and poorly lit screens filled with jumbled information are going to make sewing difficult.

It is also logical that an interface good for one person may not be good for another. For example, if you are an older sewer with declining eyesight and some hand-coordination problems, you may not do well with a sewing machine with tiny buttons placed close together. If you are sensitive to high pitches, some of the machines with shrill audio beeps may drive you crazy.

Here’s my quick, guide to getting a happy interface on your new sewing machine: Try it before you buy it. What makes good sense to a sewing machine engineer in the factory isn’t necessarily going to make a whole lot of sense to you.

Computer-connectable machines

While some sewers are satisfied with a few stitches, some want them all. So they buy a machine that accepts computer cards (or keys) that increase the patterns and stitches their machine can produce.

But some sewers don’t want to be limited to the stitches offered by the manufacturer; they want to create their own.

You can create your own stitches on some top-of-the-line sewing machines because they attach to your home computer. You can draw or paint an original design on your computer and send it directly or via memory cards to your sewing machine to be stitched. You can even scan images into the computer with an optional piece of equipment, separate the colors, and tell the machine to stitch each color separately.

If you like computers and you want to sew a motif that no one in the world has but you, then this expensive option might be for you.

WHICH KIND OF SEWING MACHINE IS FOR YOU?

The kind of machine you should buy depends on what you sew. A mechanical machine may be all you need for making curtains, clothing, or quilts. On the other hand, if you want automatic embroidery, you have no choice: The computerized machine is the only one that can store, recall, and execute those complicated designs.

I don’t particularly care how computers work, I just like what they do--most of the time. When you sew on a computerized machine, it has a different feel than a mechanical one because there are several motors and the computer brain is telling them what to do. It does take some getting used to.

With the mechanical models, you feel that the machine is connected to your foot, which is connected to your brain. The harder you press down, the faster the machine goes, but when you take your foot off the pedal, the machine may sew an extra stitch or two as it slows to stop (electronic and computerized models usually come to an abrupt stop). There is something smooth and satisfying about mechanical machines when they are running well, but I have to admit that I enjoy the benefits of computerization too, which is why I have more than one machine.

Closed- and Open-System Sewing Machines

Both mechanical and computerized machines can be closed or open systems.

In a closed-system machine, you can't add to the patterns offered. With a closed- system machine, you will always be limited to the built-in stitches. If that’s all you need or want, fine. You won’t be spending any more money on your sewing machine.

In an open-system machine, there are some built-in stitches, but you can also add to the selection by inserting a cam or a computer chip card or key. With an open-system machine, you can keep adding new stitches as they become available. You can’t have enough of these designs and they often cost plenty. The cost of collecting optional stitches and patterns might even be greater than buying the machine itself!

All kinds of mechanical and electronic gizmos tell an open-system

sewing machine what stitch to sew. Each of the cams in the foreground

represents one stitch, while the electronic cards and keys in the

background contain dozens of designs. The big brass cam is for an

industrial machine.