A space for sewing

The vast majority of home sewers don’t have the luxury of a dedicated sewing room and instead have to make do with space stolen from the guest bedroom or a corner of the living room. However a small space can be perfectly effective if you organize it well.

You are going to need a sturdy table, a comfortable, straight- back chair, and an iron and ironing board close by. If you have the iron in another room you may not want to get up and go to press the fabric when you should and your sewing will suffer as a result (see Pressing). In an ideal world the table will be big enough to cut out fabric on as well as hold the sewing machine. If this isn’t possible, then you can cut out on the floor—make sure it’s clean first.

Sewers, like knitters, quite quickly build up a stash. Delicious fabrics, gorgeous trims, colorful threads, and cute buttons are irresistible, and can take up a surprisingly large amount of space. If you don’t organize them properly then you’ll never be able to find the prefect piece when you need it. You’ll go out and buy another and your stash will just grow and grow, full of many similar things.

I like to use see-through storage as much as possible:

I keep small pieces of fabric folded in clear plastic, stackable crates and I store buttons by color in plastic button tubes. Larger pieces of fabric are folded in a cupboard, organized by fiber Ribbons and trims are wound and clipped with mini wooden clothes pegs (originally sold as office stationery, though I don’t know what you are supposed to do with them in that context).

An excellent way to store sewing spools of thread is on a DIY rack (see below left): mine is mounted on the outside of a cupboard door as I think the threads are so decorative. To make a spool rack, you hammer nails into strips of wooden molding then screw the molding to the door Slip the cotton reels onto the nails, arranging them by color f best effect. If you’re more of a shopper than a DIYer then you can buy ready-made wooden spool racks.

A capacious workbox—but not too big to carry—to hold all your sewing machine accessories and other bits of sewing kit is a must. I use a mechanic’s toolbox as it has fold out trays and lots of space, but there are many dedicated sewing boxes available.

It doesn’t really matter how you organize and store your stash and equipment as long as you know where things are and can get to them easily. Inefficient storage is almost as bad as no storage at all.

How to run a sewing machine

Once you have got your new sewing machine home, the very first thing to do is to read the manual. Even if you have used a sewing machine before, different makes and models have different operating details and , if you don’t read the instructions, you can end up damaging your machine before you’ve finished your first sewing project.

Set up the machine on a sturdy table. A decorator’s folding table, or even a gate-leg table, are not good choices because when a machine is running at full pelt it can bounce to an alarming degree if the table isn’t solid, and that really will ruin your sewing. Pull up a straight-back, armless chair—a dining chair is good, but not a wheeled office chair as they move too easily—and check that the machine is at the right height for you to operate it comfortably. Can you reach the power pedal easily without stretching your leg? Is the power cable safely out of the way and not stretched tightly to the machine so that if you trip over it you’ll pull the machine off the table? Is the machine high enough for you to see the fabric going under the needle without craning your neck? But low enough for you to sew without having to lift your arms uncomfortably high? All ok? Excellent!

With the manual read, the machine set up, a medium straight stitch selected and a piece of fabric to experiment with chosen, you are ready to start sewing. The first thing to do is to sew a line, check the stitch tension, and adjust it if necessary (see Tension).

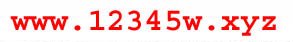

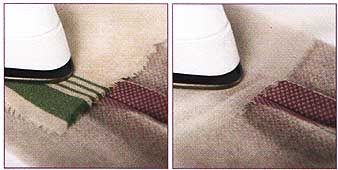

Then you need to get your hands in the right position. Novice sewers sometimes hold the fabric as shown on above right, with one hand clutching the front edge and the other at the back pulling the fabric through. This isn't how to sew. The feed dogs feed the fabric through the machine at a rate controlled by how hard you press the power pedal; you don’t need to help them do their job.

Pulling the fabric like this is also an easy way to bend the needle. They are only slivers of metal and they bend easily, and then you can have all sorts of tension problems (see Tension).

Your job is to guide the fabric so that it passes under the needle where you want the stitching to be. To this end, have both hands resting lightly on the fabric, fairly flat and quite close to the presser foot, as shown on below right Obviously you want to avoid sewing your fingers, but that's reasonably easy to do. NEVER take your eyes off the needle when it’s moving. If someone calls you, stop sewing, then look up. Don’t sew in front of the television where you’ll be tempted to glance at the action on screen.

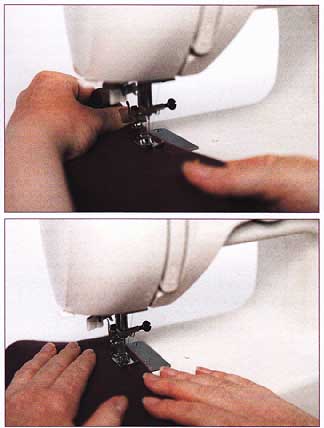

Position the fabric under the presser foot with the edge against one of the marks on the throat plate (see Sewing Straight Lines). Get comfortable in your chair and put your hands on the fabric. GENTLY press the power pedal. As the fabric runs under the needle and away from you, keep moving your hands so that they stay in the same position in relation to the needle, and gently steer the fabric so that the edge of it stays against the same mark on the throat plate.

Get used to how the fabric moves under the needle, then press the pedal a little harder Sew back and forth across the piece of fabric, changing speeds and stitch patterns until you are comfortable sewing this may take more than one session. However it’s well worth continuing to experiment and practice on non-lovely fabric until you are really confident with your machine before starting a project. If you are still at the practice stage, any project will suffer and you’ll be discouraged and that’s never good.

(top) The wrong way to hold the fabric when sewing. (bottom) The right

way to steer the fabric when sewing.

Fabrics, threads, and stitches

There is an absolutely huge range of fabrics available to today’s sewer; far too huge a range to discuss in detail here. On these pages there is an overview of the most popular sewing fabrics, plus a little advice on threads and stitches.

Fabrics

There’ll usually be two main reasons why you choose a fabric for a project; one is practical—how suitable the fabric is—and one is aesthetic—how much you like the fabric. Try not to choose a fabric solely for the second reason, as it could mean that your project just doesn’t work out no matter how carefully you sew.

From the top the fabrics in this pile are:

Lace Most modem lace fabrics are made from man-made fibers, though you can buy gorgeous, and expensive, silk and cotton lace. Lace is mainly used for bridal and evening gowns, overlaid on another fabric. It isn’t especially difficult to sew, though very delicate and vintage lace can be fragile. Use a fine needle from an 8/60 to an 11/75.

Lining fabric Generally made from synthetic fibers, lining materials come in a myriad of solid colors and great patterns. I love using fancy lining; even if no one else sees it, you know it's there and it makes a garment that bit more special. Linings are slippery and can be really tricky to sew, so I recommend basting (see Basting). For real luxury, you can buy silk lining fabric that feels wonderful next to your skin. Sew synthetic lining with an 11/75 or a 12/80 needle and silk lining with an 11/75 or finer

Tweed This is a traditional Irish wool tweed and is thick and heavy—ideal for a warm winter coat. It’s easy enough to sew, though as it’s such a chunky weave it does fray quite easily. Sew it with a 14/90 or 16/100 needle.

Silk This is dupioni silk, which is probably the easiest silk fabric to sew as it’s the least slippery. However it frays madly, marks easily, and will shift around given the chance. Having said that, silk looks and feels so lovely that it’s hard to resist for a special dress. Baste your seams (see Basting), finish all raw edges (see Finishing Edges), and be very careful of watermarks when pressing (see Pressing). Sew silk with an 11/75 needle or finer

Suedette A fake suede fabric made from synthetic fibers, this comes in a limited range of colors. It’s not the easiest fabric to sew because, like velvet, when two layers are right sides facing they try to “creep” along one another and create an uneven seam. Firm, short-stitch basting (see Basting) will help keep this fabric under control. Lightweight suedette can be sewn with a 12/80 or 14/90 needle. For heavier suedettes (and real suede) use a 14/90 or 16/ leather needle.

Wool Versatile, available in different weights, colors, and patterns, and easy to sew, wool is a wonderful fabric. Be careful pressing it (see Pressing), as too much heat and steam can felt the surface. Sew lightweight wools with a 12/80 needle, moving up to a 16/100 for the heaviest weights.

Printed cotton The most popular sewing fabric in the world. You can buy cotton fabric in almost any color and design you could want, and it has many different names. Do check the fiber content on “cotton” fabrics as they can have a man-made fiber mixed in, which you may or may not want. Remember that with large-scale patterns you may want to pattern-match at the seams, so you’ll need to buy extra fabric and baste the seams (see Batting). Generally easy to sew, choose an 11/75 needle for the lightest weight cottons—such as chambray— going up to a 18/110 for thick cotton duck. Medium-weight dressmaking cotton can be sewn with a 12/80.

Satin Often made from synthetic fibers, satin can be lovely to look at and really horrid to sew. It slips, shifts around, marks at the first possible opportunity, and often doesn’t press well. If you’re absolutely set on using satin, baste (see Basting) everything within the seam allowances and sew with an 11/75 needle.

Velvet This is velvet with a crushed finish, which does make this a slightly more forgiving fabric than straight-pile velvet. However velvet is for experienced sewers only: it’s probably the most difficult fabric there is to sew beautifully. You need to baste (see Basting) every seam using irregular long and short stitches, ideally sew it with a walking foot (see Sewing Machine Accessories), and press it on a special needle-board with paper under the seam allowances to stop them making an impression on the right side. And it frays like nothing else on earth. If you really, really must have velvet, then sew it with great care and a 12/80 or 14/90 needle.

Solid-color cotton All the attributes of printed cotton with none of the pattern- matching issues. Perfect!

Corduroy Usually made from cotton— sometimes with synthetic fiber mixed in—corduroy is hardwearing and fairly easy to sew. In a similar way to velvet, the furry finish can “creep” a little when you are sewing two pieces right sides together so basting (see Basting) is a good idea. Use a 14/90 needle to sew corduroy.

Threads

The golden rule for threads isn't to buy cheap ones. They’ll usually be poor quality, will snap, fray, and there won’t be very much on the spool so you’ll run out quickly

To avoid potential laundering complications, sew fabrics with thread made of the same fiber whenever you can. So, use cotton thread for cottons, silk thread for silks, and polyester thread for man-made fibers and for woolen fabrics, as there is no such thing as wool thread.

Rayon and metallic threads are generally used for machine embroidery (see Free-motion Embroidery) and should be sewn with a metallic or embroidery needle, which have a very sharp point and an elongated eye to help them pierce the fabric smoothly and easily.

Stitches

Basic manual machines might offer fewer than ten different stitches, while

the computerized sewing machines can produce dozens of fancy stitches, so we

can’t look at everything here. However, most of the time you’ll only use a

few stitches and we can look at those.

Below, from the left these stitches are:

Straight stitch There are three different stitch lengths shown here. A very short stitch, a medium stitch—the one you’ll usually use—and a long stitch that’s used for gathering and machine basting.

Stretch straight stitch This is a more elastic version of straight stitch and should be used to sew stretchy woven and knit fabrics.

Zigzag stitch Used to finish edges (see Finishing Edges), this stitch can be set to different widths and tightness.

Satin stitch This is a wide, tight zigzag stitch used for edging appliqué motifs (see Appliqué).

Tricot stitch This is the version of zigzag stitch that you use to finish the edges (see Finishing Edges) of stretchy fabrics.

Overcast stitch Another stitch that’s used to finish edges (see Finishing Edges).

Box stitch Used to join pieces of batting for quilting (see Quilting). Overlap the edges of the batting by 3/8” (1cm) and sew a line of box stitch along the overlap for a smooth, non-bulky join.

Embroidery stitches The last two stitches are automatic embroidery stitches. These can offer a quick and easy way of adding detail to a project.

Pinning

Putting pins in pieces of fabric to hold them together may not sound like it needs any instructions, but there are a couple of tricks that’ll make your machine sewing easier and help prevent you pricking yourself more often than absolutely necessary.

Pinning for machine sewing:

Pin like this and you’ll never have the annoyance of the head of the pin facing the needle as you sew toward ft. making it difficult to take out

Match the edges of the fabrics to be joined and have the raw edge facing away from you. If it’s a hem, fold the edge up and have the fold facing away from you. Starting at the point where you’ll start sewing, put in pins with the heads facing to the right. As you sew the seam the heads will all face you, ready to be easily pulled out before the needle reaches them.

Pinning for basting:

If you’re pinning prior to basting, then do it like this to avoid pricking yourself as you sew.

Match the edges of the fabrics to be joined and have the raw edge facing toward you. If it’s a hem, fold the edge up and have the fold facing toward you. Starting at the point you’ll start basting, put the pins in with the heads facing to the right. As you baste toward them the heads, not the points, of the pins will be facing you.

Pinning pattern pieces:

Pinning paper patterns to fabric needs to be done carefully and well to make sure that the piece of fabric you cut out is in fact the same shape as the paper pattern piece.

Firstly, make sure the fabric is smooth and flat. If it has wrinkles or folds, press them out (see Pressing). Lay the pattern piece on the fabric and smooth it flat with your hands: if it’s very wrinkled, then iron it with a warm, dry iron. Put in lots of pins, making sure that all points and valleys are held to the fabric. The full length of each pin must be within the pattern piece so that you don’t nick the blades of your fabric scissors when you cut around the paper

Sewing over pins

My grandma, who taught me to sew, didn’t hold with this and I never do it, but other sewers

I know do. I include the technique here, but if you’re going to use it, do so with caution.

Match the edges of the fabrics to be joined and put the pins in at right angles to the raw edge, leaving the heads protruding. Sew the seam fairly slowly, sewing over the shafts of the pins.

Take the pins out once the stitching is complete. The reasons I don’t hold with sewing over pins are firstly that you quite often hit a pin with the needle, at best making an irregular stitch and at worst breaking the needle. Pins can wrinkle the fabric if they’re not placed properly, and then you sew the wrinkle into the seam. Finally, if the fabrics need holding together while you sew then it really doesn’t take long to baste them.

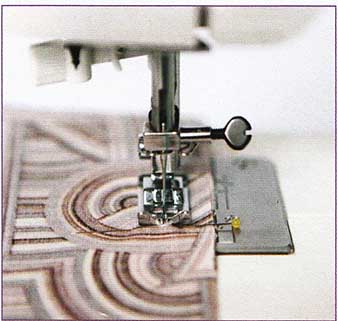

Cutting out

Accurate cutting is essential for accurate sewing. The aim is to cut the

fabric while keeping it as flat as possible on the work surface: lifting the

fabric almost guarantees wobbly cut edges.

Fabric scissors with bent handles allow the blades to cut close to and parallel to the work surface, lifting the fabric only a little, without your having to contort your hand into an odd position.

Open the blades as wide as is comfortable for your hand and slip the lower blade under the fabric where you want to start cutting. Close the blades smoothly, cutting the fabric, but don't close them fully, just before the tips of the blades close, open them wide again and slide the lower blade further under the fabric along the cutting line. Cutting this way (without fully closing the blades) will help avoid snags and dips in the cut edge.

Basting

In today’s hurry-along world, anything that takes a little more time is often cast aside whether or not it’s useful, and basting can be so very useful. I’m not saying you should always baste, but for slippery fabrics, shaped seams, trims, and neat zippers, pinning and hoping won’t usually be enough.

Seams and hems

For seams or hems in fabrics that aren’t inherently tricky to sew (see Fabrics), you only need to baste if the seam is shaped or the hem is curved.

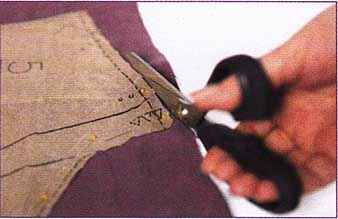

Pin the fabric along the basting line (see Pinning for Basting, opposite).Thread a slim needle with thread the length of the line to be basted plus 6” (15cm). If this is ridiculously long and impossible to use, then you’ll need to baste the line in two sections.

Sew a line of running stitch, with stitches about 3/8” (1cm) long, along the basting line.

The basting line doesn’t need to be measured and marked, as ft doesn’t matter if it's a bit wobbly. The stitches don’t have to be neat and even, though they should be firm and not too long or they won’t do their job.

Slippery fabrics and fabrics with pile — such as velvet — should always be basted and it’s best to use the long-and-short technique. This involves making firm stitches that vary in length between ¼” (5mm) and 3/8” (1cm): the irregularity in stitch length helps to keep the layers of fabric from shifting.

Taking the needle in and out of the fabric to put several stitches on it before pulling the thread through, as shown here, is a quick and perfectly valid way of basting a seam or hem. However when putting in a zipper or basting a tricky corner you may well find it better to make individual stitches.

Where to baste

One of the most common mistakes novice sewers make is to baste precisely where the line of machine sewing will be. They then have to spend time picking out the basting stitches without damaging the machine stitches.

So, whenever possible, baste a little distance from where you will machine sew. For a seam with a standard 5/8” (1.5cm) seam allowance, baste about 3/8” (1cm) from the edge of the fabric. If you are machining a hem and will have the edge of the presser foot against the fold, then baste right next to the fold.

Pressing

When you’re making a sewing project, you should be using your iron almost as much as your sewing machine. Proper accurate pressing will make the most enormous difference to your sewing, on both a practical and an aesthetic level.

The practicalities of pressing

There is a difference between pressing and ironing. Ironing involves moving the iron around on the fabric and is what you do to freshly laundered garments. Pressing involves placing the iron in one spot, then lifting it and placing it in another without dragging on the fabric.

If at all possible, set up your iron and ironing board in the room you sew in (see A Space For Sewing).You should press your project every time you sew a section of it, and if the iron is to hand and you don’t have to leave the room, then you are more likely to be good about doing this.

Check what temperature your fabric can be pressed at. Generally, cotton and linen can be pressed with a hot iron, wool with a warm iron and synthetics with a cool iron. However this isn’t a firm rule and introducing steam can change things, so you need to test a scrap of fabric first to check that you have the right temperature.

Before using steam on a fabric, check that any watermarks you might make on the fabric will disappear Drop a little water on to a scrap of the fabric and iron it dry, then check that no watermark remains. Steam has two functions: it helps take out very stubborn folds and creases and it will “set” fabric into a shape. How firm the “set” will be depends on the fabric, and it will lose its shape when washed and then need re-pressing. Most irons have a steam function and will produce different amounts of steam at different temperatures. Alternatively, spray the fabric with water using a spray bottle and then press it to create steam, or use a dampened pressing cloth.

My favorite pressing cloth is an old cotton tea towel with the hems cut off to prevent them making impressions on the fabric. A piece of silk organza can be a useful pressing cloth as its translucency enables you to see what you are doing, but it needs frequent dampening.

My favorite cotton pressing cloth; An organza pressing cloth.

Pressing seams

“Press seam open” is a common instruction in sewing books and involves laying the fabric flat, opening out the seam allowances (see Sewing Straight Lines), and pressing them fiat against the wrong side of the fabric.

1. The first stage in pressing a seam open is to press it flat. Without opening out the fabric, press over the line of stitching you have just done to help the stitches sink into the fabric.

2. Then open the fabric out and lay it fiat, right side down. Open out the seam allowances and press them fiat. Turn the fabric over and check that the edges of the allowances haven’t made an imprint on the fabric. If they have, then you need to slip strips of paper under the seam allowances and press them again.

Tailor’s ham

This is a small, very firm cushion that you can lay a curved seam over (see Inward Curve and Outward Curve) so that you can press it open without pressing it fiat at the same time. It’s a really useful piece of equipment. You can buy a ham, but it’s easy to make your own.

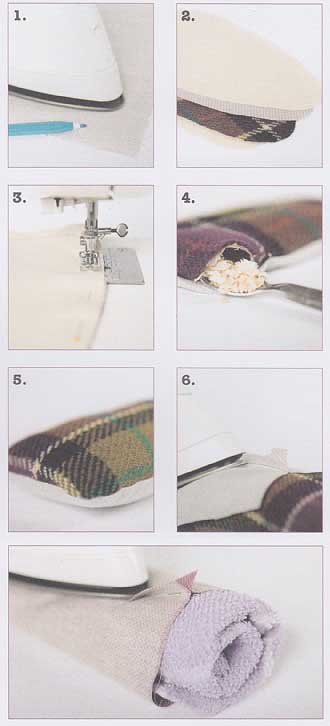

1. Lay your iron on a piece of dressmaking cotton fabric and draw around it. Curve out the sides a little and round off the corners to make a classic ham shape, then add 2” (5cm) all around.

2. Cut out the shape and use this as a template to cut the same shape once in woolen fabric and twice in thick cotton. Lay out a thick cotton ham shape with the dressmaking cotton shape face up on top of it, then the woolen shape face down and finally the other thick cotton shape. Pin the layers together

3. Set the sewing machine to a medium straight stitch. Taking a 3/8” (1cm) seam allowance, machine around the edges, leaving a 4” (10cm) gap.

4. Turn the ham right side out through the gap. Fill it with sawdust (the type sold as bedding for hamsters is ideal), spooning ft through the gap. You need to stuff the ham very firmly indeed, so use the spoon to press the sawdust down inside the ham so that you can force in as much as possible.

5. Hand-sew the gap closed using over-sewing stitch to complete the ham. If after a few weeks the sawdust has compacted and the ham feels a bit soft, then you’ll need to unpick the gap and push more sawdust in.

6. Lay a curved seam over the ham and press it open. Having one side of the ham in wool and one side in cotton allows you to use a high heat on the cotton side if it’s needed.

Pressing sleeves

You can make or buy a sleeve roll, which is a sausage-shaped version o a tailor’s ham, but I prefer to use a towel because it can be made to fit any size or length of sleeve.

Roll the towel up so that it slides inside the sleeve, filling it without stretching it. You can now press the sleeve seam open without pressing the sleeve fiat. This is also useful when you’re ironing if you don’t want pressed lines running down your sleeves.