The body is a series of systems, each performing specialized functions necessary to the animal’s survival. When something goes wrong, we see it in terms of where the breakdown occurs. Only then can we diagnose the cause and arrive at the proper treatment. So, let’s look at the dog from the stand point of symptoms — where they might appear and what to watch for.

SKIN

Itching, scratching, hair loss, or the appearance of reddened, inflamed patches on the skin are all symptoms of trouble. When they appear, you should try to determine the underlying cause — whether the dog has fleas or has come into direct contact with an irritating substance — and take the sight steps to solve the problem. If the condition spreads, resists treatment, or appears to be more serious than a simple dermatitis, a veterinarian should be consulted.

The problem in diagnosing skin diseases is that there is an enormous overlap in the symptoms. Furthermore, you may be dealing with more than one condition simultaneously: dermatitis caused by a flea bite can result in the dog’s tearing its skin in an attempt to relieve the itching, leading to a secondary bacterial infection.

DERMATITIS. Nonspecific inflammations of the skin may be caused by both allergies and direct contact with irritating substances. Both result in redness, intense itching, and breaks in the skin oozing serum, which forms scabs.

Allergic dermatitis can be due to an enormous variety of allergens, including pollen, fleas, grasses, rugs, foods, and the like. Once other common dermatological diseases have been ruled out, skin tests can be used to deter mine the specific agent. Internal medications, corticosteroids, and antibiotics can be used to treat the infection, and antihistamines to relieve the allergy. If these methods fail to yield results, a series of inoculations may reduce sensitivity to the allergen.

CONTACT DERMATITIS. This is frequently the result of bathing with harsh soaps or detergents, or of lying down on surfaces that have been sprayed with caustic agents and chemicals. In the latter case, the affected area may give a clue if the owner is unaware of the dog’s exposure to the irritant. Any remaining caustic substance is removed and corticosteroids are applied. The dog should also wear an Elizabethan collar to protect the area from further irritation.

PYODERMA. This is a bacterial infection of the skin, which may be either superficial or deep. Among the superficial pyodermas are puppy impetigo and juvenile pyoderma, common in dogs less than a year old. Pustules (acne) are found on the chin, lips, ears, and the rear of the abdomen. Lip-fold pyoderma is frequently found on the lower lips of Saint Bernards and other breeds with drooping skin in back of the canine teeth. Vulvar-fold pyoderma is a problem with obese females. The vulva is recessed in excess skin folds, crevices that are moistened when the dog urinates, resulting in bacterial infection. In both lip-fold and vulvar-fold pyodermas, the physical defect must be corrected surgically. Treatment for the pyoderma will be discussed below.

Deep-skin pyodermas are the most difficult to cure — often, all that can be managed is to keep the infection under control. These are identified by location. Interdigital pyodermas, for example, often result from a benign cyst between the toes. To relieve the irritation caused by the cyst, the dog licks or nibbles the foot until a reddened dermatitis appears. The cysts eventually break and bacteria enter.

Generalized pyodermas, which are also deep, may affect from 6o to 70 percent of the dog’s body and are among the most frustrating to treat. Infected animals are believed to lack the normal immunological defenses to fight infection, and bacteria can multiply without resistance by the body’s mechanisms. These dogs suffer constant discomfort from sores and itching, in addition to having a bad odor.

Superficial pyodermas, if there are no complications, can be treated effectively at home in the following manner.

1. Clip all hair away from the affected areas.

2. Cleanse the skin around the lesion twice daily with a mild soap such as Ivory, Massengill’s antiseptic douche powder (1 tablespoon of powder to 1 quart of warm water), diluted hydrogen peroxide (50 percent solution), or diluted Betadine solution ( percent).

3. Apply bacitracin or the ointment prescribed two to three limes daily.

4. If the infection is severe enough, oral antibiotics may be necessary. A prescription will be needed from your veterinarian.

5. If the inflammation is severe, oral corticosteroid may be necessary. Again, a prescription will be necessary.

6. Protect the areas from the dog by bandaging if it is feasible and using an Elizabethan collar. Tranquilizers, if they are prescribed by your veterinarian, are also useful.

7. If pyodermas are deeply infected with bacteria, the dog should be taken to the veterinarian for skin cultures and to have dead tissue removed under anesthesia. Vaccines may also be necessary.

8. Inter-digital pyodermas should be soaked for twenty to thirty minutes in Massengill’s powder in solution (1 tablespoon powder to 1 quart warm water), or Epsom salts or Dum-Boro’s solution, which will aid in drying up the oozing infection.

RINGWORM

RINGWORM. A skin disease caused by a fungus, this affects both humans and animals and can be transmitted by cowling into direct contact with either the infected dog or objects, such as bedding and furniture, which have become infected. The typical lesion is a circular, dry, crusty patch with short broken shafts of hair. These are most commonly found on the head, face, and ears, but may appear on other parts of the body. The lesions themselves are used in diagnosis, as well as ultraviolet light (Woods lamp), special fungal cultures, and microscopic examination of the hair shaft. Ringworm is treated with an oral fungicide and creams applied to the lesions. The dog’s environment should be cleaned to avoid re-infection or exposure of others.

SEBORRHEA. Best known as dandruff, this is found most frequently in cocker spaniels, schnauzers, dachshunds, and German shepherds. While the cause is still not certain, hypothyroidism, in part, is strongly suspected. There are three known types of seborrhea:

Seborrhea sicca — a dry form with scales. Seborrhea oleosa — an oily form.

Seborrhea dermatitis — similar in appearance to the other forms of dermatitis.

Rather than cure, because the cause is not known, the treatment is de signed to control the disease. Anti-seborrheic shampoos (Seleen, Fosteen, Sebafon, Thiomar, and Pragmatar) are helpful and should be used, depending on how severe the condition is, once to twice a week. If dry skin is a problem, either as a result of the disease or of bathing, fill a spray bottle of the type used for glass cleaners with diluted Alpha-ken bath oil (1 part to 9 parts of water). Spray a fine mist over the dog’s coat. After working it into the coat for ten to fifteen minutes, wipe off the excess with a damp rag. This will act as a coat conditioner as well as helping to keep the dandruff under control. This can be used from one to three times a week, depending on the need.

If itching is a problem, short-term conticosteroids may be needed to keep the animal from injuring itself.

HORMONAL SKIN DISEASES. These are characterized by symmetrical bald patches and changes in the thickness and pigmentation of the skin. There is no itching. The four most common of these skin disorders are:

1. Cushing’s syndrome (hyperadrenocorticism) — which causes bald patches on the back and abdomen. The remaining hair in these areas is rough looking and can easily be picked off. The skin is frequently quite thin. This condition affects the adrenal glands and, as a secondary effect, increases the levels of corticosteroids. Medication can be used to destroy portions of the adrenal gland to reduce production of the corticosteroids, or both adrenal glands can be surgically removed. If this is done, deoxycorticosterone acetate must be administered orally or by implantation as a supplement.

2. Hypothyroidism — inadequate production of thyroxine and triiodothyronine hormones by the thyroid. This results in not only bald patches but thickened, darkly pigmented skin. Thyroid extract or synthetic thyroid is used as an oral supplement.

3. Sertoli cell tumor — a testicular tumor that produces excess estrogen. The results are bare patches along the neck and on the back of the thighs. The skin is even thicker and more heavily pigmented than in hypothyroidism. Castration is the only treatment.

4. Hypotestosteronism — quite rare, occurring in a few males castrated at an early age. The symptoms include both bald patches and darkened pigment. Diagnosis is usually based on the history of early castration and eliminating other possible causes. Synthetic testosterones, administered orally, can be used.

hormonal skin disease

TUMOR. “Tumor” means any abnormal growth — and it should be pointed out that tumors may well be benign, localized and showing no tendency to spread, and definitely not cancerous. They can also be cancerous, malignant, and quite likely to spread. Tumors on the skin often include benign epidermal cysts, papillomas (warts), basal cell tumors, perianal gland adenoma, and lipomas — to name a few. Other potentially malignant skin growths are squamous cell carcinomas, malignant melanomas, mast cell sarcomas, and mammary gland adenocarcinomas.

Because of the possibility of malignancy, any growth on your dog’s skin should be brought to your veterinarian’s attention. Early diagnosis and removal may prevent spreading. No matter how insignificant it might seem, any growth removed should be sent to a lab for confirmation of the tumor type.

EYES

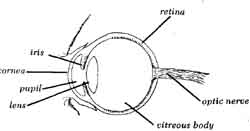

The eye — a complex network of muscles, nerves, and blood vessels — is far too delicate an organ to be treated at home without the guidance of a veterinarian. Because there is always the possibility of a permanent loss of vision, any indication that your dog is having problems, regardless of the cause, should receive professional attention as early as possible. Common symptoms include excess4ve tears, conjunctivitis or red eye, swelling, bluish haziness of the eye, pus discharge, aversion to sunlight, pawing at the eye, or rubbing the face on the ground. Some frequent causes include:

HEAVY TEARING (epiphora). In toy breeds, this may be the result of a con genital malformation of the “lacrimal lake.” In poodles, stains on the fur that run down the muzzle from the inside of the eye are a common indication of this problem. Another possible cause may be extra eyelashes touching the sensitive cornea — these can be removed by the veterinarian. The problem may also be due to allergies, plugged tear ducts, corneal ulcers, entropion (the edges of the eyelids are curled in), and conjunctivitis.

Once the veterinarian has removed the underlying cause, the eye is usually flushed with a mild substance such as boric acid and applications of antibiotics or corticosteroids, which prevent formation of excess scar tissue.

CONJUNCTIVITIS (red eye). Inflamed eyelid membranes, this is usually ac companied by heavy tearing and a pus discharge. The causes may be physical irritation, bacterial or viral infection (often canine distemper), or allergies. Medication usually consists of flushing the eye with a mild boric acid solution, antibiotics, and corticosteroid solutions.

DRY EYE (keratoconjunctivitis sicca). This is most common in toy breeds, such as Pekingese and pugs, with bulging eyes. The surface of the cornea becomes dry because there is insufficient tearing. This can lead to ulceration, inflammation of the interior of the eye (iritis), darkening of the cornea, and conjunctivitis with pus discharges. Treatment is focused on relieving the symptoms by supplying artificial tears (o. to 1.0 percent methylcellulose) four to six times daily and medication for any ulcers (see Corneal Ulcers), and surgery if necessary. Pilocarpine can be added to the dog’s food to stimulate tears but, because it has certain side effects, is used only under a veterinarian’s supervision.

CORNEAL ULCERS. These breaks in the tissues lining the surface may be either superficial or deep. Indications of pain, squinting, and sensitivity to sunlight are frequent symptoms. Causes can vary widely, from exposure to chemicals in soaps and detergents or lye, wounds, and infections. Superficial ulcers can usually be healed quickly, in five to seven days, using pupil dilators (mydriatics) to reduce pain and antibiotics to control infections. Deeper ulcers are treated similarly unless there is reason to fear perforation to the interior of the eyeball, which would require surgery to support the cornea and prevent rupture while the ulcer healed.

GLAUCOMA. An increase in the internal pressure of the eye due to excess fluids, this causes pain, swelling, and loss of vision. It can result from infections, displacement of the lens, tumors, accidental injury, or may be congenital. While the production of these fluids is a normal process, the pressure results from the fact that drainage is impaired. The affected eye has a hard, bulging appearance, the pupils are widely dilated, and the cornea turns blue. Eventually vision is impaired. Both drugs and surgery can be used to reduce the pressure temporarily, but there is no assurance that the problem will not recur.

CATARACTS. This condition, in which the lens becomes opaque, may be congenital. It can also be a result of the normal aging process or associated with a disease such as sugar diabetes. In the latter case, treatment would focus on curing the underlying cause. Generally, however, there is no way to control this problem medically. If the animal becomes blind, surgical techniques can be used to remove the cataracts if tests establish that the optic nerve and retina are functional.

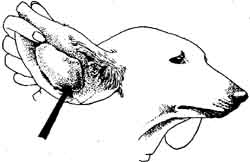

MEDICATION. How to apply eye medication: when you administer either drops or ointment, the most important thing is to prevent accidental eye injuries if the dog moves suddenly. Using the proper technique, you can make sure that the hand holding the tube or bottle containing the medication will move with the dog’s head. This should be the hand you normally favor. Place the fingers of your other hand under the dog’s lower jaw and lilt its head upward at an angle of 45 degrees, halfway between the vertical and horizontal. Put the base of the hand with the medication, which should be held between the thumb and the first two fingers, on the dog’s forehead. Holding the applicator between 1 and 2 inches away from the eye, gently drop or spread the medication over the surface.

EARS

The ears are the source of some of the pet owners’ most frustrating problems, which can be both chronic and difficult to treat. Infections are not always the cause and treatments vary widely. Among the broader classifications of ear problems are:

Obstructive otitis, in which hair prevents air from reaching the deeper areas of the ear canal, is common in poodles. As a result, ear wax and moisture accumulate, creating a good environment for bacterial growth and infection.

medicating the ears

Ceruminous otitis is an irritation of the ear tissues resulting from excessive production of ear wax.

Suppurative otitis, infections in which the ear canal becomes inflamed and pus accumulates, are caused by highly resistant organisms such as pseudomonas, proteus, and clostridial bacteria. These chronic infections are often complicated by the presence of yeast organisms, which are believed to be responsible for their resistance to treatment.

Proliferative otitis is a secondary effect of many of the conditions de scribed above. As a result of chronic irritation, the folds of the inner ear thicken to as much as three to four times their normal size. Air cannot reach the inner ear, and material within it is prevented from draining.

Otitis media or interna, a nonspecific infection of the innermost portion of the ear, may affect a dog’s sense of balance.

In general, the primary means of treating infections are designed to clean and flush out the ears. Antibiotics may be applied directly and taken orally. When infections prove resistant, cultures and solutions can be used to change the level of acidity in the ear. Occasionally, in severe cases, surgery is needed to provide drainage.

Ear hematomas, injuries to the small blood vessels within the ear caused by the dog’s shaking its head and scratching the irritated area, are a common side effect of infections. Blood from the ruptured vessels forms soft, often painful clots between the cartilage of the ear and the skin. These can be relieved by draining the blood from the mass but, because of the likelihood of recurrences, surgery is often recommended.

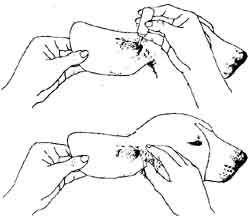

MEDICATION. How to apply ear medication: with one hand hold the dog’s ear so that it won’t move its head. With the other hand, hold the tube or dropper one or two inches above the ear so that you won’t accidentally poke deep inside if the dog does move. Once the medication is applied, still holding the ear, massage the base with the other hand.

NOSE

The commonest symptom of nose problems is sneezing. An occasional sneeze need be no cause for worry, but if the sneezing persists, this may be evidence of trouble, either acute or chronic. In diagnosing the cause, the veterinarian will consider a number of factors, including:

The dog’s environment — has it been exposed to grass lawns or other materials that might cause an allergic reaction?

Where it may have traveled — funguses causing nose infections are prevalent in some areas.

The dog’s age — sneezing can indicate nasal tumors in their early stages.

The dog’s dental condition — a tooth abscess may have extended into the nasal sinuses.

Nasal discharges — are they clear and watery, or thick and puss-filled?

Whether the irritation is in one or both nostrils.

In most cases, sneezing problems can be treated with antibiotics, antihistamines, and nasal decongestants. If they are severe or resist these less complicated treatments, tests will be used to isolate the cause and arrive at a more effective solution.

MOUTH AND THROAT

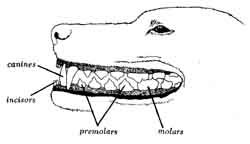

Puppies have twenty-eight teeth. Each side of the upper and the lower jaw will include three incisors (which are the nibbling teeth toward the front of the mouth), one of the tusklike canines, and three premolars, or chewing teeth. Between its second and third month the puppy should be examined by a veterinarian for indications of any congenital abnormalities — such as an overshot or undershot jaw — that might cause future problems.

When the puppy is around six to seven months old, these baby teeth are shed and replaced. New teeth will also appear— another premolar on each side of the upper and lower jaws, two of the larger molars on each side of the upper and three on each side of the lower — bringing the total to forty-two. When the adult teeth have emerged, the dog should receive another dental examination so that any baby teeth that have not been shed, or any extra teeth, may be removed.

TARTAR AND CALCULI. These form on the dog’s teeth and have become much more common problems for pet owners since the introduction of soft, canned dog foods. Feeding your dog large bones and hard biscuits will usually keep the accumulation under control, but your pet, especially if it is one of the smaller breeds, should receive periodic dental examinations in order to avoid abscessed teeth, periodontitis, or gingivitis. Periodontitis, an infection of the tissues around the tooth sockets, and gingivitis, gum infection, are common in cases of poor dental health. Both are capable of causing so much pain when the dog opens its mouth that it may refuse to eat.

In some cases, the infection of an abscessed tooth — most frequently the fourth upper premolar — may extend through a nasal sinus to drain beneath the eye. If a bad tooth infection is left untreated, it can also cause osteomyelitis (bone infection) in either the upper or lower jaw.

Treatment for severe dental diseases in dogs is similar to that given humans. The animal is anesthetized, the infected teeth are removed, and tartar and calculi removed from those that remain. Antibiotics, vitamin supplements, and oral flushes might be used to restore the animal to good health.

TRENCH MOUTH, OR STOMATITIS. This inflammation of the mucous membranes in the mouth may be caused by poor dental health but can be complicated by bacteria or fungi that are highly resistant to treatment. This infection may also result from advanced kidney disease or oral tumors. Treatment focuses on removing the underlying cause. Dead tissues are removed surgically, the area cauterized, and antibiotics or fungicides administered. Gentian violet, potassium permanganate, or B-complex vitamins may be applied to the surrounding areas. The pet owner’s role is to make sure the dog receives a good, nutritious diet and plenty of water. Usually trench mouth can be cleared up in from three to eight weeks.

TONSILLITIS. This may be the result of either dental disease or simply too much barking— a problem the owner should be as anxious to solve for the sake of his own mental health as for the dog’s physical health. The symptoms are difficulty in swallowing, loss of appetite, and, in some cases, evidence of pain when the inflamed tonsil is touched. The tonsils can also develop tumors that block the air passages and force the dog to strain for breath.

While recurring flare-ups or tumors might require removal of the tonsils, acute tonsillitis can usually be eliminated by correcting the underlying problem, administering antibiotics, and putting the dog on a semi-liquid or soft diet until the symptoms disappear.

RESPIRATORY DISEASES

KENNEL COUGH. Kennel cough, or tracheo-bronchitis, is frequent among dogs that have been exposed to the stress of simultaneous confinement in a small space and exposure to other dogs — the type of situation encountered while boarded at a kennel, at a dog show, or in a grooming parlor. In itself, it is a mild disease that will eventually disappear, even without treatment, once the dog is in a more normal environment. The cause may be any of a number of viruses that infect the upper respiratory system.

The most obvious symptom is a repeated harsh, dry cough, which can easily be triggered by gently pressing on the dog’s windpipe, or trachea. Other signs are mild fever and loss of appetite. These will normally vanish in a matter of a few days or weeks, and the only treatment necessary is antibiotics to prevent a secondary bacterial infection. If this does occur, however, matters can become more serious. A moist cough and discharges from the dog’s nose and eyes are signals that complications may have developed, such as pneumonia, necessitating a chest X-ray or other tests.

TRACHEAS. Collapsed or narrowed tracheas are common in many of the toy breeds, especially poodles and Fomeranians. The characteristic symptom is a dry, repeated cough when the dog, as owners frequently describe it, “acts as though it’s trying to get something out of its throat.” The only yield, however, is sometimes a white, foamy phlegm. This condition is apparently congenital and results either from a narrowing of the tracheal rings, the stiffened “ribs” of the windpipe, or weakened membranes at the back of the trachea. In more severe cases both conditions exist, and the dog will sound like a honking duck. Excitement or straining at the leash will worsen the cough.

The history of the breed is an important factor in diagnosis. Medication may be given to dilate the bronchial tubes, increasing air flow to the lungs, as well as cough suppressants and sedatives for occasions when the dog might become excited. These are usually sufficient and surgery is required in less than 1 percent of the cases.

PNEUMONIA. This is a condition in which pus and debris accumulate in the air sacs and tissues of the lungs; it can usually be treated successfully if diagnosed early. Possible causes include bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites, and foreign matter that has been inhaled. The usual symptoms are moist coughs, which yield matter, lack of appetite, depression, and high fevers. Physical examinations, chest X-rays, and blood tests are used in diagnosing this condition. Bronchodilators, vaporization, and expectorants are used to relieve the dog’s breathing problem and antibiotics to check any secondary infection. The actual cure, however, is based on determining and removing the initial cause. Treatment may be necessary for weeks or even months. Massive, overwhelming infection, lung abscesses, and even the loss of a lobe of the lung are common results if complications develop.

CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASES. A broad category, these diseases share the common symptoms of a hacking cough and wheezing. And, as a group, they are resistant to antibiotics. The subdivisions used in de scribing these conditions are asthmatics, allergic pneumonitis, chronic bronchitis, bronchiectasis (narrowing of the bronchi, the large air passages in the lungs), and emphysema.

When other chest conditions have been ruled out, diagnosis is based primarily on the dog’s history, examination of chest X-rays, and blood tests. Treatment is largely designed to relieve the symptoms and may include bronchodilators, vaporization, antibiotics, and corticosteroids.

CHEST TUMORS. These are often the result of cancer cells that have mi grated from a primary tumor, in the breast, for example, and been trapped by the lung’s efficient filtration system. Isolated tumors can sometimes be re moved surgically, and cancer drugs have successfully prolonged the lives of dogs with certain forms of cancer, but the picture in such cases is not generally hopeful.

It is important that older dogs with a history of respiratory problems — such as rapid breathing or a chronic cough — or that show an increasingly poor ability to tolerate exercise receive a checkup to see if a chest disease is the cause.

SKELETAL DISEASES

While dogs are subject to a number of skeletal diseases, such as rickets, hypertrophic osteodystrophy in the larger breeds, and panosteitis, there is no means by which the layman can distinguish among them or attempt any form of treatment. The essential symptom is the same: reluctance to walk. A dog evidencing this should, be taken to the veterinarian for diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

DIGESTIVE SYSTEM

VOMITING. This forceful, explosive expulsion of the stomach’s contents must be distinguished from regurgitation, when undigested food and water are eliminated without violence. A dog that frequently regurgitates should be examined by a veterinarian for pharyngeal or esophageal problems or parasites (see above), but this cannot be considered an emergency.

Vomiting, on the other hand, can indicate immediate and serious problems, particularly if there are signs of blood. While it may result from nothing more than simple “garbage hound” gastritis, it could be symptomatic of an obstruction in the digestive system due to a swallowed foreign object, kidney failure, pancreatitis, or cancers of the stomach and bowels.

The first step is to eliminate the possibility of gastritis. To control it:

1. Withhold all solid food for twelve to twenty-four hours.

2. To coat the stomach, give the dog orally Pepto-Bismol or Maalox, 1 teaspoon (5 ml) per 10 pounds body weight.

3. Do not withhold water particularly if the dog is suffering from aging conditions that make it advisable. If the water is vomited, substitute ice cubes that can be licked, or try giving the animal frequent but small amounts of water.

4. In addition the dog should be started on a bland diet such as strained chicken or beef baby foods or chopped boiled meat and rice.

Continue this for the next three to five days before slowly weaning the animal back to its normal diet.

5. If the vomiting continues twenty-four to forty-eight hours after you have begun these steps, or if there are signs of marked depression, fever, or vomited blood, the dog should be taken to a veterinarian.

DIARRHEA. This can be caused by many things. In young dogs, intestinal parasites are the most common problem. Other possibilities are too rich a diet, excessive nervousness, intestinal irritants such as plants or spoiled food from the garbage, bowel diseases such as salmonella, pancreatic and other diseases that make it impossible for the dog’s system to absorb the food, or intestinal cancers.

Most diarrheas can be treated by following the same procedure outlined above for vomiting, with the addition of i teaspoon (5 ml) of Kaopectate per each 10 pounds of body weight, administered orally, to firm up the stools and protect the intestinal lining. If the diarrhea continues or there is depression or fever or signs of blood in the stools, the dog should be taken to a veterinarian immediately.

CONSTIPATION. This can result in a dog straining so hard to relieve itself that delicate tissues become injured. Common causes include a constricted colon due to a fractured pelvis; perineal hernia; a rectal diverticulum, which is a saclike structure resulting from a defect in the mucosal tissues of the rectum, which accumulates stool and causes an obstruction; masses in the rectum or colon, such as tumors or polyps; scar tissue in the rectum or colon; and nerve damage that inhibits colonic movements and causes a large, functionless colon.

Treatment, then, must aim at eliminating the cause, if possible. This is properly the job of the veterinarian, but the pet’s owner can aid by giving symptomatic relief. This can include manually removing excess stool, disposable or suppository enemas, mineral oil or Laxatone lubricants, stool softeners such as sodium dioctyl sulfosuccinate, bulk laxatives, and, if approved by your veterinarian, intestinal stimulants.

COPROPHAGY. This condition, in which a dog eats its own or other animals’ stool, may be due either to bad puppy habits or, as a few veterinarians suggest, to an attempt to make up for an insufficient supply of digestive enzymes. Discipline and time will often succeed in breaking a puppy of this habit, but you might add some papain — found in most meat tenderizers — to the pet s diet, to aid in breaking down keratin and other proteins.

A related problem is the licking up of other dogs’ urine. This is caused by bad habits learned as a puppy, too.

FLATULENCE. Passing excessive gas is often related to diet, though no one precisely understands either the causes or the mechanism. If your dog has a problem, try changing its diet. If this fails, consult your veterinarian regarding products that might help.

ANAL GLANDS. These glands, which open into the anus at angles of about 45 degrees, produce a thick, foul-smelling substance, which enters the rectum through a tiny duct. These secretions are believed to be a lubricant and the scent to serve as a means of marking off the animal’s territory. Normally, the pressure of stool passing is sufficient to drain the two glands but the soft foods so many dogs receive today create a problem in some breeds. The glands are not sufficiently drained and start to fill up. The discomfort causes the dog to scoot along rubbing its anal area on the floor, or to lick it. The pet’s owner should then apply pressure to the glands manually to drain them. This simple operation should be performed with a rubber glove. Lubricate either the thumb or forefinger, which will be inserted slightly into the anus. Pinching down gently will locate the swollen gland, which, once found, should be squeezed until the swelling disappears. If this is not done, they will become impacted and infected, breaking through the skin as abscesses. If this happens, the abscess must be cleaned, flushed with an anti biotic solution, and hot compresses applied two to three times a day. The dog should also receive oral antibiotics.

OBESITY. This is a growing problem with pets and cannot always be blamed on the owner’s excessive generosity. Other factors include hormonal abnormalities such as hypothyroidism, metabolic rate, activity, the type of diet, and environment. Overweight dogs are prone to arthritic and back ailments and heart and respiratory problems. More serious, should the need arise, they are poor risks for anesthesia and surgery.

The answer lies in a strict diet, and you should make sure your friends and neighbors are aware of it and cooperate. Commercial (Cycle-4) and prescription (Rid, “0”) diets are available and may help. If the diet is followed carefully and the weight problem remains, a veterinarian should examine the dog for indications of a hormonal problem.

UNDERWEIGHT. Weight loss, or a failure to gain weight at the normal rate, can be very disturbing to an owner. The subject is far too broad to discuss in depth in this book, but the possible causes can be lumped into several general categories:

Insufficient calories to keep up with the dog’s metabolic demands — bluntly, starvation.

Inability to break down and absorb nutrients, possibly caused by a pancreatic problem.

Competition for nutrients by parasites.

Excessive loss of nutrients, due to diarrhea.

Disease of the heart or kidney, or diabetes mellitus. Psychological — nervousness due to stress.

Neoplasia — tumors or other abnormal growths.

Obviously, this problem requires the advice of your veterinarian.

GENITOURINARY

CYSTITIS. Inflammation of the bladder may be caused by bladder stones, growths (polyps or tumors), bacterial infections, or congenital developmental abnormalities (diverticula). The first step in treatment is to determine which is the source of the problem and to eliminate it. Bladder stones, which injure the walls of the organ, can be diagnosed by X-ray. A bladder dye study (cystogram-pneumocystogram) can detect growths or diverticula. Urinalysis and urine cultures are used in diagnosing bacterial cystitis and determining the proper treatment. The symptoms of cystitis include increased frequency and urgency of urination, a result of irritation; blood in the urine (hematuna); or cloudy, foul-smelling urine due to pus (pyuria). Bladder stones, growths, and defects require surgery. Bacterial infections can be treated with antibiotics, regulation of urinary pH, and follow-up urine cultures.

PENIS AND PREPUCE. Balanoposthitis is an inflammation of the tissues lining the penis and the prepuce, which shields it. Foreign matter accumulated between the two irritates the mucous membranes and pus is discharged from the tip. By continually licking and bothering this, the dog usually alerts the owner to the problem. Various solutions — Massengill’s (i tablespoon in 1 quart warm water), or a mild boric acid solution — can be introduced into the prepuce, and a mild bacterial ointment worked in one to two times daily and massaged back and forth within the sheath. Bacitracin ointment could be used; Panalog would be better, because it’s thinner.

PROSTATE. Prostate disease is common in dogs over six years old. The organ, which secretes the fluid carrying the sperm, may become enlarged (hypertrophy), inflamed (prostatitis), or develop abscesses, cysts, or tumors. Symptoms vary, depending on the type and severity of the condition, but they may include difficulty with bowel movements because of pressure on the colon by the enlarged organ, discharge from the penis containing pus or blood, stiff movement of the hindquarters caused by pain, and difficulty urinating. Abscesses may cause fever, loss of appetite, and listlessness. History is important in diagnosis, and physical examination will reveal an enlarged prostate. Other techniques include radiographs, possibly with dye studies, and flushes for cultures and cytological examination. Enlarged prostates may be due to a hormonal imbalance and require castration and/or the administration of estrogen-like compounds to induce shrinkage. Prostatitis, if there are no abscesses, can be treated by castration and the use of antibiotics. Abscesses, cysts, and tumors require surgery on the prostate itself.

TESTES AND SCROTUM. Problems in this area are likely to arise first when the dog is around six months old. One or both testicles may fail to descend into the scrotum, as they normally should at this age. This may require surgical removal, since retained testicles have a tendency to become tumorous as the dog grows older.

Scrotal dermatitis occasionally results when a dog has been lying on a surface that irritates the scrotum. The sac becomes inflamed, swollen, and painful; the skin may become discolored and peel. The scrotnm should be generously rinsed with water to remove any caustic substances and a steroid- antibiotic ointment applied to soothe and keep it lubricated. For best results, the ointment should be prescribed by a veterinarian. The dog should wear an Elizabethan collar or muzzle so that he will not be able to lick the area.

Orchitis, inflammation of the testes, usually involves only one testicle. It may be a secondary effect of an injury or an infection such as Brucella cards. Another cause could be twisting of the testicle (torsion), which prevents blood from reaching the tissues. Antibiotics and hot compresses can be at tempted but are not usually successful, and castration may be necessary.

Testicular tumors of three types — seminoma, interstitial cell, and Sertoli cell — are occasional problems. All can be identified by an asymmetry in size, with the tumorous teste becoming large and irregular, while the normal opposite teste becomes small and soft. The Sertoli cell tumor, however, is much more spectacular in its effects. It produces estrogen, and may result in the loss of hair in identical lateral strips on both the dog’s sides, and thickening of the skin. He may also develop female traits, breast development and a tendency to squat while urinating, and attract other males. The prepuce will droop. When the possibility of cancer of the testes has been eliminated, castration is the proper treatment for testicular tumors.

VAGINA AND UTERUS. Vaginitis is common in young females prior to their first heat. The inflammation causes a yellowish green discharge from the vagina that the dog may continually lick and bother. Cystitis is a frequent side effect and may result in increasingly frequent and more urgent urination. While the cause may be in part hormonal, bacterial infections, especially Streptococcus spp. and E. coli, are frequently involved. Antibiotics taken internally, mild astringent douches such as Massengill’s powder in solution (1 tablespoon in 1 quart warm water), occasional hormonal supplements, and ovariohysterectomies are used in treatment.

Pyometra is an infection of the uterus, occurring three to eight weeks after the dog has been in heat. Hormonal stimulation creates an environment favorable to bacterial growth. F. coli, the most common organism involved, causes the organ to swell with pus from its normal pencil size to that of a salami. Toxins in the bloodstream cause excessive thirst and frequent urination. Other symptoms include listlessness, vomiting, and loss of appetite. In severe cases, kidney function may be impaired, leading to endotoxic shock. If the cervix is open, a vaginal discharge containing pus and blood may be seen. If it is closed, the dog’s belly will swell because of the lack of drainage and she may become seriously ill. Pyometra is an emergency condition and the animal should he taken to the veterinarian as soon as any symptoms are noted.

In the case of bitches with a valuable breeding potential, antibiotics and douches to irrigate the uterus may be attempted, but the favored treatment is ovario-hysterectomy to remove the source of the infection.

Female genitourinary system

male genitourinary system

HEART DISEASE

Heart disease can be the result of a congenital defect or may develop as part of the aging process. The commonest, and most dangerous, condition is. congestive heart failure, most frequently caused by chronic fibrosis of the heart valves.

The heart is a complex pump, an organ divided into four chambers. Valves close the chambers off from one another when the heart contracts. If a valve fails, there is a backfiow of blood into the chamber it has just left. The characteristic symptom of this condition is a heart murmur, a sound caused by the turbulence as the blood reenters the chamber from which it has been ejected.

A heart murmur does not automatically signal the onset of heart failure — it is merely a danger signal. The heart, a remarkable organ, compensates for a defective valve by increasing its size; there is a limit, however, to how large it can grow. When this is reached, the heart begins to fail.

A secondary effect of this is that fluid backs up into the lungs (pulmonary edema), and the patient is quite literally in danger of drowning. The first symptoms of chronic heart failure are an increasing coughing of fluids, often in the middle of the night. Appetite decreases and the patient will some times faint. In severe cases, the tongue and the mucous membranes inside the mouth will have a bluish appearance. Breathing will be in rapid pants, with mouth open.

Any of these symptoms should be brought to the attention of your veterinarian, who can evaluate the dog’s condition with X-rays, an electrocardiogram, and blood tests to check out other organs, particularly the kidneys and liver. An animal that collapses with a heart attack should be handled as little as possible and subjected to minimal stress. The veterinarian will give it oxygen, diuretics (water pills) to decrease the fluid in its lungs, and Digitalis to stimulate the heart’s muscle contractions so that it will slow down and do a more efficient job of pumping. Once its condition has been stabilized, the dog will continue to receive digitalis and diuretics. Because salt retains fluids in the body, a low-salt or salt-free diet will be prescribed.