Raising Food and Forage for the Small Place

Grains and grasses were staples of the old-time self sufficient farm. Grasses, in the form of hay or fresh pasturage, supplied the bulk of the diet for the farm animals. Grains provided flour for homemade bread, supplementary feed for the livestock, and raw materials for everyday needs. An acre of corn can fill a year's grain requirements for a pig, a milk cow, a beef steer, and 30 laying hens. Still another use for pasture plants and grains is green manure-crops that are raised for the purpose of being turned under the soil to improve it.

Raising grain or grass does not require large acreage or costly machinery. Indeed, if you can grow a lawn, you can raise grains and grasses as crops. A plot of land only 20 by 55 feet can supply all the wheat an average family of four will need in a year. The crop can be harvested, threshed, and winnowed with hand tools and ground into flour in a tabletop mill.

Like any other crop, grains and grasses require soil preparation, fertilization, and attention. However, they require much less care than a good-sized vegetable garden.

Planting rates

------------------

Type of grain

Amount of seed per acre

Land area needed to grow 1 bushel

Wheat 75–90 lb. 10’ × 109’

Oats 80 lb. 10’ × 62’

Field corn 6–8 lb. 10’ × 50’

Barley 100 lb. 10’ × 87’

Rye 84 lb. 10’ × 145’

Buckwheat 50 lb. 10’ × 130’

Grain sorghum

2–8 lb. 10’ × 60’

-------------------

Note: These figures are estimates; actual yields may be affected by weather, soil, and variety of seed.

------------------

Sowing the Cereal Grains

The most important food plants in the world are the cereal grains. Whether eaten directly, processed into bread, or used as animal feed, they provide the basic nutritional needs of almost every man, woman, and child on the face of the earth. North America is particularly suitable for growing grain. Almost every one of the major grains flourishes over vast regions. The sole exception is rice, a crop whose cultivation is restricted to the Deep South and southern California.

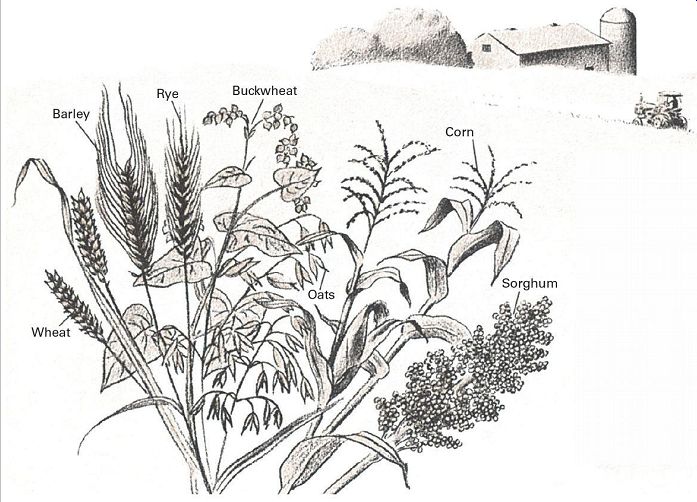

-------------- Grains are the seeds of certain members of the grass family,

such as wheat, corn, and rye, that are used for food and animal feed. Buckwheat

is also considered a grain, although the plant is not a grass but a member

of the knotweed family.

Corn and wheat are the two most widely grown grains in the United states, accounting for hundreds of thousands of acres and millions of bushels. The major use of wheat is for flour; the major use of corn is for animal feed. Both also have many industrial applications. The other grains have more specialized uses, but all are nutritious, high yielding, and good for small-scale farming.

Wheat, barley, and other hardy grains can be grown as either spring or winter crops. Winter crops are sown in early fall, grow a little, and then go dormant during the cold months. When spring returns, they shoot up and are ready to harvest in midsummer.

Spring crops are usually grown where winters are too severe for fall-sown grains. They are sown about the time of the last killing spring frost and are ready for harvest in early fall. In general, the winter crops yield more heavily. There are separate varieties for spring and fall sowing. Spring wheat will not survive the winter if planted in fall; winter wheat may not have time to mature before autumn frost kills it if it is planted in spring, especially if the growing season is short.

Most grains do best on well-tilled soil of average fertility--too much nitrogen makes them grow overly lush and topple over. Corn, however, needs highly fertile soil. Before planting, the soil should be plowed and disked or roto-tilled and lime and fertilizer added as needed. The seeds can be broadcast (flung out) by hand or with a hand-cranked seeder, as in planting a lawn. To ensure even coverage, go up and down the plot lengthwise as you sow; then go over it again at right angles to your first direction. After sowing, till or rake the soil to work the seeds in. If the plot is large, sow the grain with a drill, a mechanical device that spaces out the seeds in straight rows at precise depths. Except for field corn and sorghum, grains need virtually no care until harvest time. Corn and sorghum should be planted in widely spaced rows so that they can be cultivated while small.

To prevent soil depletion and the buildup of pests and pathogens, grain crops should be raised as part of a rotation system with other crops. Your county agent can advise you on the best rotation plan for your area. A typical plan might be corn the first year, followed by alfalfa, winter wheat, vegetables or soybeans, and pasture in succeeding years.

The Major Grains

Wheat, the world's leading bread grain, requires a cool, moist growing season and about two months of hot, dry weather for ripening. Wheat grows 3 to 4 feet tall and turns golden brown when ripe. It is ready to harvest when the grain is hard and crunchy between the teeth.

Wheat can be sown in fall or spring. Winter wheat should not be sown before mid-September: it may grow too much before cold weather arrives and be killed by freezing as a result. Early planting also exposes winter wheat to attack by the destructive Hessian fly.

Five kinds of wheat are commonly grown in the United States and Canada. They are hard red winter wheat, used for bread; soft red winter wheat, used in cakes and pastries; hard red spring wheat, the best for bread; white wheat, used mainly for pastry flour; and durum wheat, used for spaghetti. Wheat supplies the best-balanced nutrition of all the grains.

Oats are the highest in protein of all grains. They are a hardy crop that thrives in a cool, moist climate and cannot tolerate drought. Oats are sown as a spring crop except where winters are mild. A mature oat plant stands 2 to 5 feet tall. Oats can be harvested while they still have a few green tinges. They should be gathered into shocks and left to dry in the field.

Rye, once a major bread crop, is now grown mainly for stock feed and whiskey. It is also much used for green manure and as a cover crop. Rye grows 3 to 5 feet tall and is almost always sown in fall. Although its per-acre yield is less than that of wheat, it can produce crops on poorer soil than wheat and tolerates cold, drought, and dampness better. Most rye bread contains at least 50 percent wheat flour. Old-timers often mixed rye and corn flour to make a bread called Rye-and-Injun.

Buckwheat is raised for its nutlike, triangular seeds. Its dark, strong-flavored flour is excellent for pancakes.

Buckwheat grows about 3 feet high; it prefers moist, acid soil and hot weather. Because it matures rapidly (60 to 90 days), buckwheat is often used as a second crop after winter wheat or early vegetables.

Barley does best with a long, cool ripening season and moderate moisture but adapts well to heat and aridity. It also tolerates salty and alkaline soils better than most grains. In warm regions barley is usually planted as a fall crop; in colder areas it is planted in early spring. Barley is used for animal feed, beer, and malt. It is also used in soup and as a whole-grain dish.

Sorghum resembles corn but with narrower leaves and no ears. There are four types of sorghum: grain, sweet, grass, and broomcorn. Grain sorghum grows to about 4 feet tall, and its seeds are used mainly for animal feed.

They also make nutritious porridge and pancakes. Sweet sorghum is raised for syrup and silage, grass sorghum finds use as pasturage and hay, and broomcorn is valued for the long, springy bristles of its seed heads, used in making brooms. Sorghum tolerates heat and drought well.

Plant it about 10 days after corn. Corn, first domesticated by American Indians thousands of years ago, leads all other grains in the United States in acreage and harvest.

Corn raised for grain is not sweet; it is called field corn to distinguish it from the sweet corn we raise as a vegetable.

Field corn is used for animal feed, cornstarch, hominy, grits, and a variety of breakfast cereals and snack foods. A limited amount is used for corn bread. Field corn is taller and yields more heavily than sweet corn but is planted and cultivated in the same way. It can be harvested easily after the plants are dead and dry by snapping the ears off the stalks. The ears of corn should be taken under shelter as soon as possible to protect them from rain and mold. The corn should be husked before storing.

Corn can be fed to animals while still on the ear, but for most purposes it should be shelled-that is, the kernels should be removed from the cob. Shelling can be done by rubbing an ear of corn briskly between your hands, or you can buy a hand-powered sheller.

Corn: America's unique contribution is an Indian discovery

From Field to Flour

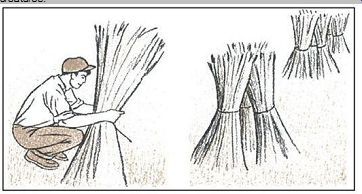

Harvesting is the same for all grains other than corn. After the grain has been cut, gather the stalks into sheaves and stack them to dry in the field until no trace of green is left.

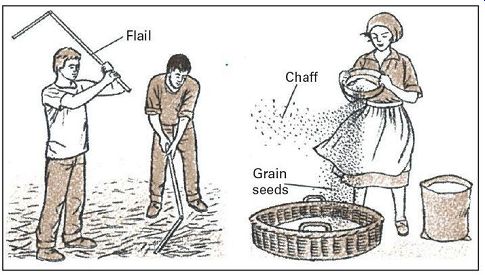

To thresh the grain, lay the sheaves on an old sheet on a hard surface and hit the seed heads with a flail, broomstick, or baseball bat to knock the seeds loose. To separate the grain from the chaff, or loose husks, toss it in a sheet outdoors on a breezy day, or pour grain and chaff back and forth from one container to another. On a calm day a fan can supply the air current.

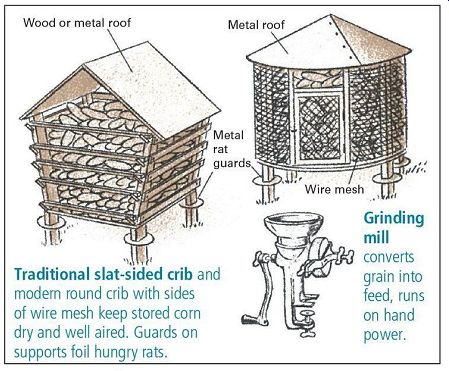

Store grain in covered metal trash can or a wooden bin that has been rat proofed with wire mesh. Stored grain must be kept thoroughly dry to prevent mold. Grain can be ground in a small mill designed for home use (some are equipped with revolving stones that duplicate the old-time stone-ground flour). Small batches can be run through a heavy-duty food blender.

Grassland Management for Hay and Pasture

If you have a horse, a cow, or other livestock and an acre or two of unused land, an excellent way to put that land to work is by planting it to grass. In addition to providing essential pasturage and hay for the animals, grass protects the soil from erosion and furnishes a habitat for a myriad of small creatures.

------------

1. Make a sheaf by tying an armful of grain stalks into a bundle. Use twine or twist grain stems into a cord.

2. stack sheaves together to make a shock. Leave them outdoors to dry in the sun. Do not store damp grain.

------------

3. Thresh the grain to separate the kernels. A simple flail can be made of two sticks joined loosely.

4. Final step is winnowing threshed grain by using the wind to blow away chaff and other small particles.

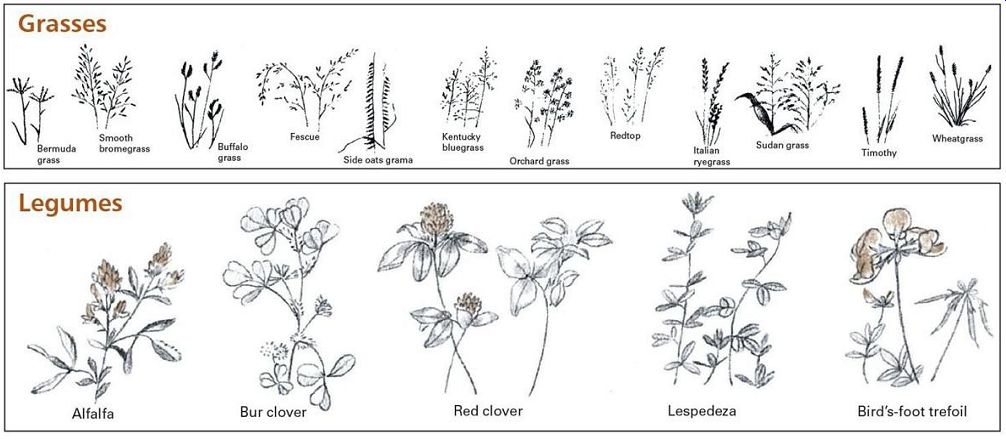

Managing a grassland is like managing a small ecosystem. The trick is to keep various plant species-not just grasses but also such legumes as clover and alfalfa--in balance so as to provide a nutritious diet for livestock while at the same time maintaining or increasing the fertility of the soil. By regulating the intensity of grazing, by mowing, and by minor adjustments of the soil's mineral content, the landowner can favor the growth of one plant species or another and keep many troublesome weeds under control without resorting to chemicals.

Grasslands fit well into crop rotations, and for maximum production you may wish to establish a grassland on a cultivated field. Such rotation also prevents the buildup of pests and pathogens by depriving them of hosts. You may also decide to put steep, uneven, or rocky land into permanent grassland. The only prerequisites are sunlight for at least half the daylight hours and sufficient moisture. In areas of low rainfall moisture can be supplied by irrigation or sprinklers.

To establish a pasture on cultivated land, plow and harrow the soil and lime it, if needed, to bring the pH to between 6 and 7 (slightly acid). Till in manure, compost, or an all-purpose chemical fertilizer. The seed can be broadcast or planted in very close rows using a seed drill.

For hay you may wish to plant only one crop, such as alfalfa or timothy. For pasture a mixture is preferable, since livestock suffer from bloat on a pure diet of fresh legumes.

Consult your county agent for the best combination of forage plants. A mixed pasture is ecologically sound. A variety of plants lessens their vulnerability to pests and disease, and the legumes supply nitrogen, which the grasses need for good growth.

Do not let livestock graze in a pasture until the plants are well established and about a foot tall. This gives them time to build up food reserves in their root systems. Repeated grazing closer than 3 or 4 inches depletes the food reserves of the forage plants, so they grow back poorly.

Eventually they die off, leaving the land open to invasion by weeds and brush. However, properly controlled grazing and mowing help keep weeds and brush under control.

-------------

Legumes: green nitrogen factories

Legumes add nitrogen to the soil in which they grow by means of symbiotic bacteria that form nodules on their roots. These bacteria convert nitrogen from the air into forms that plants can use.

However, each type of legume needs a different strain of bacteria, and the proper type may not be in the soil when the legume is planted. Legumes will grow without their bacteria, but they then take nitrogen from the soil instead of adding it. To ensure success, inoculate the soil with the proper bacteria, obtainable at most garden supply stores.

---------------

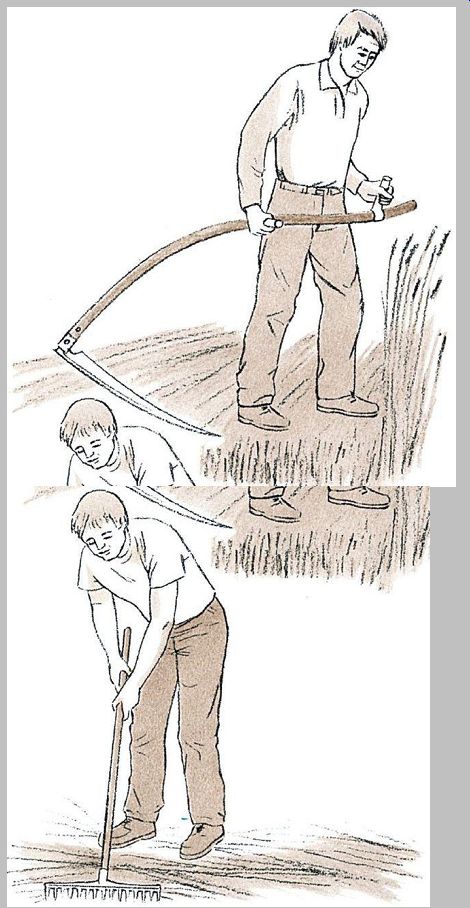

When scything, cut with a rhythmic, sweeping motion of the upper body. Stand with your feet well apart for balance. Keep the scythe blade sharp, and wear heavy work boots for greater safety.

---

Let hay dry partially on the ground after cutting; then rake it into long piles, or windrows, to complete drying in the open air. Windrows should be 6 to 12 in. high and loosely heaped so that air can circulate freely. Turn the wind rows over periodically.

----------------------------

To renovate an old or run-down pasture, plow it up thoroughly, apply lime and fertilizer, and reseed the land with desirable varieties. Grasses will often come back vigorously from their roots in the soil, so little reseeding may be required. Legumes, however, must usually be reseeded, sometimes every year. If the old pastureland is overgrown, as it often is, grub out brush and young trees or keep them mowed close to the ground. Eventually they will be starved out.

Hay and Haymaking

Although the terms "hay" and "straw" are often confused, the two are actually quite different. Hay is made from grass, legumes, or other forage plants that have been cut while young and tender and cured by drying. Straw consists of the stalks of grain after threshing or the dried stalks and stems of other farm crops. Hay is palatable, nutritious livestock feed; straw is useful as bedding but contains little food value. Legume hay is an excellent source of protein for livestock; clover and alfalfa are leading legume hay crops.

Whether made from grasses or legumes, the best hay comes from plants that are cut in the early blooming stage: at this point they have their highest nutritive value. If allowed to set seed before cutting, the plants become tough, dry, and woody, like straw. Hay can also be made from immature oats and other grains, which should be cut while the kernels are soft and milky.

It is important to cut your hay on a clear day so that the hay can dry on the ground in the sun's heat. After drying for a day or two, rake the cut hay into long parallel rows. These rows, known as windrows, should be turned over periodically with a pitchfork or by machine to expose all the hay to sun and air. The hay is ready to store when its moisture content is down to 15 percent. A simple way to judge its readiness is to pick up a handful of stems and then bend them in a U shape. If they break fairly easily, they are ready for storing. If they are pliable and take a lot of twisting to break, the hay is still too damp. If the stems are so brittle that they snap off easily, the hay is too dry-safe to store but with much nutritional value lost. Hay that is too dry is also subject to leaf shattering-the leaves, which are the most nutritious portions of the plants, break off and are lost.

Selected forage crops

--------------------

Variety--What you need to know

Alfalfa Perennial legume; the leading hay crop in all sections but the southeast. Grows 2'-3' tall; deep roots (8'-30') tap moisture in subsoil and make plant drought resistant. Tolerates alkali; fails on acid soils. Very rich in protein; raised chiefly for hay but also used in pasture together with grass

Bermuda Perennial grass; grows best in southeast. Forms sod. Primarily a pasture grass, though some strains grow tall grass enough to cut for hay; a good companion for legumes. Tolerates heat well Bromegrass, Vigorous perennial grass; 3'-4' tall.

Forms dense sod. Thrives in Corn Belt and Pacific Northwest; under smooth irrigation on Great Plains. Used for pasture, hay, erosion control.

Withstands drought, extreme temperatures Buffalo Low-growing perennial native to Great Plains; forms dense, matted turf 2"-4" tall. Noted for tolerance of grass drought, heat, cold, alkaline soil.

Withstands heavy grazing

Bur clover Annual legume related to alfalfa. Used for winter pasture; needs mild, moist winters Clover important genus of legumes; five species predominate in United states: red, white, alsike, ladino (giant white), crimson. Height ranges from a few inches to 3'. May behave as annuals, biennials, or perennials depending on climatic variations and soil. Used for hay, pasture, silage, green manure Fescue, tall Perennial grass can be grown in most parts of United states; important in southeast and Pacific Northwest. Used for pasture and hay; grows 3'-4' tall; very tolerant of wet soils Grama grass Perennial grass; native to Great Plains.

several species; height ranges from 2"- 3". Primarily used for pasture Kentucky Perennial grass; grows in most of United states except southwest and at extreme elevations. From 12"-30".

Bluegrass tall; best suited to permanent pasture.

Leading pasture grass of Canada and United states

Lespedeza--A cloverlike legume. Two annual species important in United states.

Height from 4"-2". Most important in southern Corn Belt and south. Used chiefly for pasture; in south grows tall enough for hay also Orchard Perennial grass; vigorous, long-lived.

Tolerates shade and wide range of soil types; likes moisture.

Grass--Forms bunches 2'-4' tall; used for hay and permanent pasture Redtop Perennial grass; tolerates heat, cold, acid, and run-down soils. Grows up to 3' tall. Used for hay and pasture; often sown with timothy Ryegrass, Fast-growing annual, 2'-3' tall. Used for winter pasture in south; hay and pasture in Pacific Northwest.

Italian--Excellent poultry pasture A grasslike sorghum; annual; reaches 3'-8' in height. Tolerates heat, drought.

Sudan grass--Used primarily for pasture and fresh chopped feed; also makes excellent hay. Most important in south but grows as far north as Michigan Timothy One of the oldest cultivated grasses; perennial. Thrives in cool, moist climate.

Grows in bunches 20"-40" tall. Primarily used for hay, especially for horses Trefoil, Hardy perennial legume. Tolerates damp, acid, and infertile soils. Raised from Vermont to eastern Kansas, bird's-foot also Pacific Northwest. Grows 20"-40" tall; used for pasture and hay Wheatgrass Perennial grass; five important species, some native to West. Grows 2'-4' tall.

Some types form sod; others are bunch grasses. important in dry lands of West; used for hay and pasture

-----------------------

Good hay often has a tinge of green even though thoroughly dry. (Alfalfa hay should be bright green.) Hay can be stored loose or in bales. In either case it should be protected from the weather. Wet hay may rot into good compost, but it makes bad feed. It can go moldy and may then poison the animals to which it is fed; in extreme cases it will ferment, and the heat produced will start a fire. If you have no barn or shed, a tarpaulin over the hay will provide a fair degree of protection from the effects of rain and snow.

Sources and resources

Books and pamphlets:

Elkins, Donald M. and Darrel S. Metcalf. Crop Production: Principles and Practices. New York: Macmillan, 1980.

Nation, Allan. Grass Farmers. Jackson, Miss.: Green Park, 1993.

Willis, Harold L. How to Grow Great Alfalfa . . . & Other Forages. Wisconsin Dells, Wis.: H. L. Willis, 1993.

===