Part Five--Skills and Crafts For House and Homestead

It is my special pleasure to behold the lines of handmade things and to see the patina of seasoned wood and to feel a patriotic pride in the good workmanship there.

-Eric Sloane, Diary of an Early American Boy

Handicrafts were once part of everyday life. People thought no more of making their own candles, spinning their own yarn, or mixing their own paints and glues than modern folks think of vacuuming a rug or screwing in a new light bulb. In those days crafts were not just for artists and hobbyists-they were the survival skills of average men and women. Today, Americans are beginning to rediscover these old-time home skills: for fun, for economy, but most of all for the feeling of independence that comes when one makes do for oneself. Many of the topics covered in "Skills and Crafts for House and Homestead," such as spinning, tanning, and soap making, can be practical money savers as well as enjoyable creative activities. And a few, among them weaving and basketry, yield satisfaction on many levels: pride of accomplishment, pleasure in artistic creativity, and the gratification of doing something with your own hands.

Natural Dyes--A Rainbow of Color From Common Plants

Indigo blue and madder red were the favorite colors of early migrants to the New World. Both had to be imported, but the permanent, deep shades they produced made them worth the expense. Experimentation did occur, however, and settlers learned to create rich yellows and beiges from natural dyestuffs native to America. The bark of the American black oak tree became a particularly valuable source of bright yellow and was eventually used by commercial dyers throughout Europe. When home dyers needed mordant (one of several chemicals that make dye colorfast), they turned to an apothecary or tanner. In areas lacking these suppliers, settlers relied on the metal leached from the copper or iron pot in which the dye was cooking or else employed a concoction of stale urine and ashes. Then, as now, color results varied from batch to batch-but, with luck and skillful use of dyes and mordants, the tones were rich, mellow, and durable.

Start by Scouring

Because all fibers contain oils that keep mordants and dyes from penetrating, it is necessary to clean or scour them before beginning the dye process. To scour 1 pound of fiber takes about 3 gallons of water. As with all dyeing procedures, soft mineral-free water is best. If the tap water in your area is hard, use rainwater instead or add commercial water softener to the tap water. To scour grasses, do not use any detergent or soap; simply soak them in water until they are soft. For other fibers, once the water is softened, add enough mild detergent to make it sudsy, then immerse the yarn and gradually raise the temperature. Silk should be allowed to simmer for 30 minutes and wool for 45 minutes. For cotton or linen, also add 1/2 cup of washing soda to the detergent solution to make the scouring bath, and boil the fibers rather than simmering them for one to two hours. When scouring is completed, allow the bath to cool, then rinse the fibers in soft water until no suds remain.

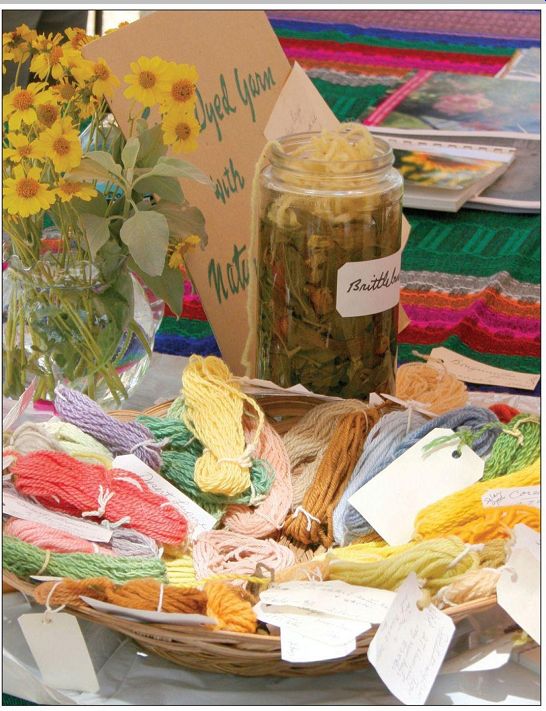

Naturally dyed yarn at a market. Marigolds and dahlias are among the several kinds of flowers that give bright, long-lasting dyes. Most flower heads will produce a shade of yellow no matter what color their petals.

----------

How to Prepare and Use a Dyebath

A dyebath is prepared by soaking and cooking the raw dyestuff in water. Use either an enamel or stainless steel pot (unlike aluminum, copper, and cast iron, these materials will not give off chemicals that affect the dye).

Your dye pot should be large--4 gallons or more--and you will also need a wooden spoon or dowel for stirring and some cheesecloth in which to wrap the dye substance.

Prepare the dyestuff so that as much color as possible can be extracted. Leaves and blossoms should be shredded. Twigs, bark, and roots should be cut up into small pieces, and nut hulls should be crushed. Pick out foreign particles and remove extraneous parts of plants.

Wrap the dye substance in cheesecloth, put it into the pot, and cover with water. (Some dye materials must first be soaked in cold water.) Cook until the dyebath becomes richly colored, adding more water as needed to keep the dye substance covered. After cooking, remove the cheesecloth bag and its contents or strain the liquid through a sieve. To the concentrated dye, add enough cold water to make a bath in which the yarn can float freely-4 gallons is adequate for 1 pound of wool. Wet the fibers, add them to the bath, and bring slowly to a simmer for animal fibers or to a boil for plant fibers. Cook until the desired shade is reached, turning the fibers occasionally with the wooden spoon or dowel so the bath penetrates evenly. Then allow the fibers to cool, either in or out of the bath, and rinse until the water runs clear. You may also cool the yarn by rinsing it in successively cooler baths. After gently squeezing out excess moisture, hang the skeins to dry.

If there is any color left in the dyebath, you may reuse it to produce lighter shades. A dyebath can be stored for several days by refrigerating it. Freezing will keep it for several months, and by adding 1 teaspoon per gallon of the preservative sodium benzoate, you can preserve the dye for a month without refrigeration.

Collecting and Storing Dyestuffs

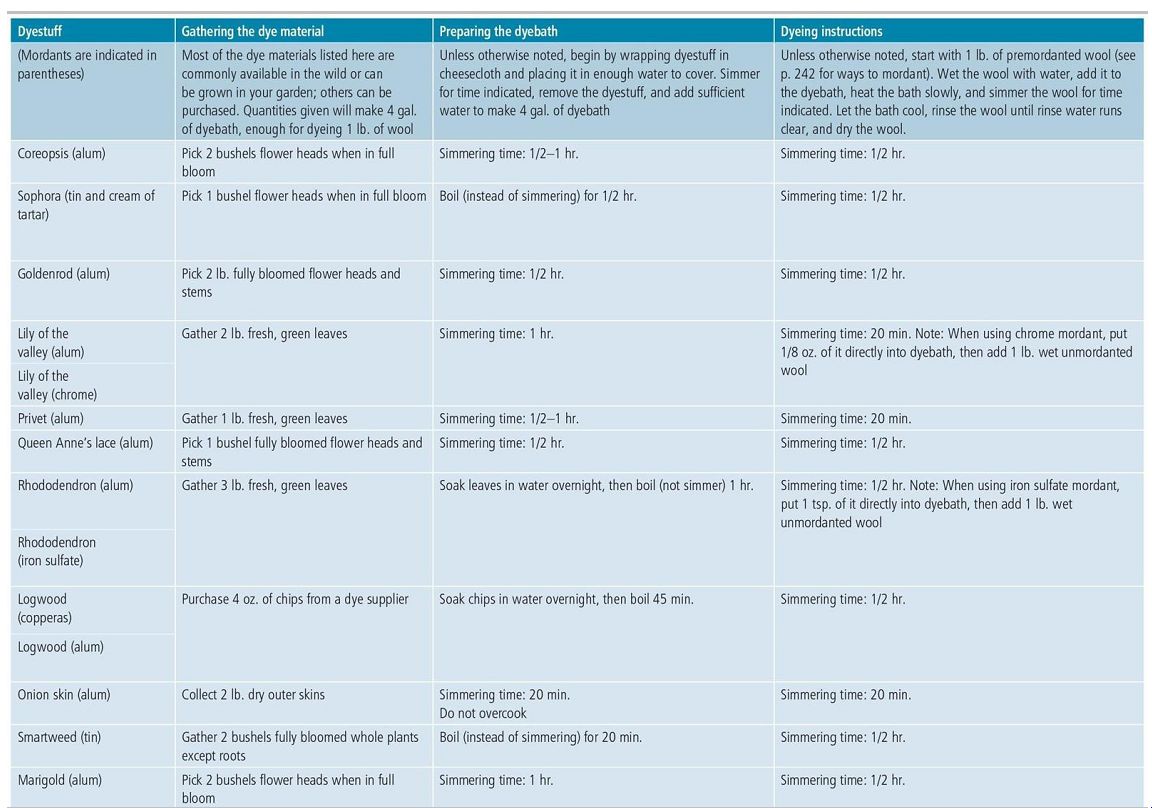

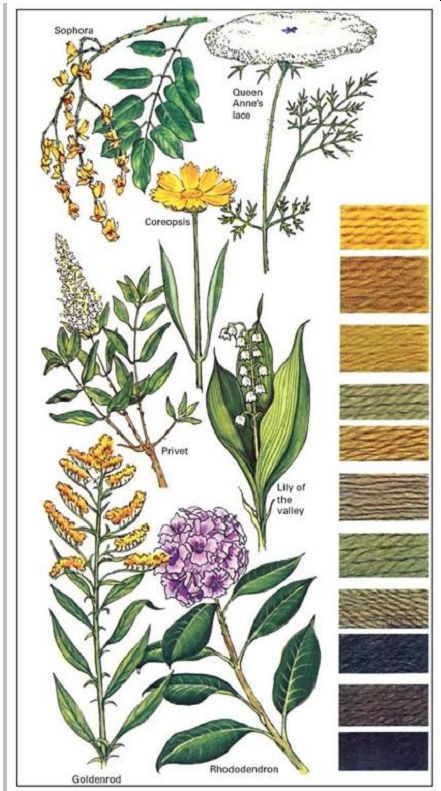

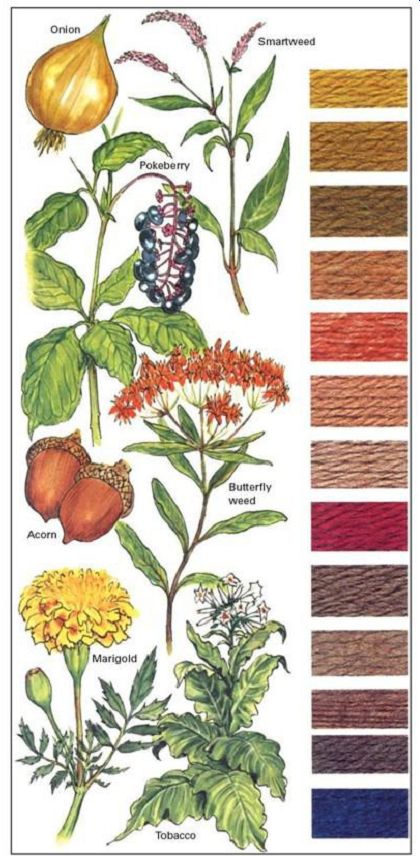

The first step in making your own dyes is to gather the dyestuffs. The chart is a guide to common, naturally occurring sources of dyes and to the colors they will produce. In general, the plants are easy to identify; if you need more information, consult a good botanical guide that illustrates leaves, flowers, bark, buds, and other distinctive characteristics.

You not only need to collect the right plants, you also need to collect them at the right times. Flowers should be picked just after they reach full bloom. Roots, bark, and branches should be from mature plants-do not pick new branches. Nuts should be fully ripe and even a little aged (but should not have lain on the ground through the winter).

Acorns, for example, are best just after they have fallen from the tree, while black walnuts benefit from lying on the ground until they become spotted. Berries make the best dyes when picked fully ripe.

Although fresh dyestuffs produce the strongest dyes, most plants can be stored for later use. Twigs, leaves, nuts, blossoms, bark, and roots can be dried. Spread them in a single layer in a shady, well-ventilated spot, turning them occasionally for faster drying. A window screen set on bricks makes a good drying rack because it lets air circulate underneath as well as on top. Plants with stems may be hung in bundles to dry. Once drying is complete, store the dyestuffs in brown paper bags or other containers through which air can circulate. Berries should not be dried but can be kept for several months if frozen. Freeze them unwashed, either whole or pulverized into juice.

Mordants: The Stuff That Makes Dyestuffs Colorfast

Mordants are chemicals that help to keep dyes from fading, changing color, washing out, or rubbing off. They may also affect the final color so that a single dye can produce a variety of shades depending on what mordant is used with it. Textiles may be mordanted either before or after dyeing, or the mordant may be added directly to the dyebath. It is simplest to do the mordanting first. Once the fibers are mordanted, you can soak them in the dyebath for as long as necessary to achieve the desired shade without worrying that long exposure to the mordant will damage the yarn.

For mordanting, use an enamel or stainless steel pot for cooking and a wooden rod or spoon for stirring. Dissolve the chemical in about 4 gallons of lukewarm soft water (use commercial water softener if necessary), then thoroughly pre-wet the textile and immerse it in the mixture. Bring the bath slowly to a simmer or boil. Once mordanted, the yarn may be dyed immediately or dried and saved for future use.

The most commonly used mordants are alum, blue vitriol, chrome, copperas, tannic acid, and tin.

Alum (aluminum potassium sulfate) causes least change in color. Use 1 ounce per gallon of water and simmer one hour to mordant wool, silk, or other animal fibers. For cotton or linen use 1 1/3 ounces of the mordant per gallon of water and boil the fibers for one hour.

Blue vitriol (copper sulfate) sometimes colors fibers green. Use 1/4 ounce per gallon of water and simmer one hour to mordant animal fibers. For cotton and linen use 1 ounce per gallon and boil for one to two hours.

Chrome (potassium dichromate) often strengthens colors. Use 1/8 ounce per gallon for animal fibers and simmer for one hour. With linen or cotton use 1/2 ounce per gallon and boil for one to two hours. Because chrome mordanted fibers are turned brown by exposure to light, keep mordant pot covered and dye the yarns immediately or store them in complete darkness. Keep the pot covered when dyeing the chrome-mordanted fiber.

Copperas (iron sulfate) grays colors. For wool use 1/8 ounce per gallon of water and simmer for 30 minutes. For linen or cotton use 1 ounce per gallon and boil for one hour.

For greater color fastness add 3/4 ounce of oxalic acid, dissolved in water, to the mordant bath. Some dyers sadden colors (dull them) by adding 1/8 teaspoon of copperas to 4 gallons of dyebath for the last few minutes of dyeing pre-mordanted fibers. Dissolve the mordant in a little water and remove the fibers from the bath before adding the solution.

Dyeing with indigo

--------------

Because indigo is not water soluble, special techniques are employed to dissolve it and to use it as a dye. start by mixing 1 oz. of washing soda in 4 oz. of water, then add 1 tsp. of indigo paste. shake 1 oz. of hydrosulfite (available from a pharmacy) over the solution and stir gently. Next add 2 qt. of warm water, heat to 350°F, and let stand for 20 minutes. To complete the dyebath, shake another ounce of hydrosulfite over the top and stir gently again.

Immerse wet yarn in the yellow-green solution for 20 minutes. When the yarn is removed from the bath and exposed to air, it will turn blue.

Tannic acid tends to turn fibers brown. For animal fibers use 1 1/4 tablespoons per gallon of water and simmer one hour. Use 2 1/2 tablespoons per gallon for plant fibers and boil them for one to two hours.

Tin (stannous chloride) brightens colors, particularly reds and yellows, but it can easily damage fibers. To prevent damage, mordant fibers for as short a time as possible and wash them thoroughly after mordanting. For both animal and plant fibers use 1 ounce per gallon of water and simmer for one hour. Some dyers use tin in combination with another mordant by adding 1/8 teaspoon of tin to 4 gallons of dyebath for the last few minutes of dyeing. As with copperas, remove fibers, add the tin in solution, then replace the fibers.

Mordants are sold by most pharmacies and chemical supply houses. They are available in a range of purities.

The so-called chemical grade, which is less expensive than purer grades, is sufficient for dyeing purposes. Mordants are strong chemicals and must be handled carefully. Use them in a well-ventilated place and keep the mordanting pot covered to prevent chemicals from escaping into the air.

Never use mordant pots to cook food. Chrome requires particular care since it is highly poisonous.

General Tips on Textiles, Fibers, and Dyes

Fibers derived from animals, particularly wool from sheep, tend to take dye more easily than either plant fibers or synthetics. In addition, the colors you get with wool and other so-called protein fibers will be darker and brighter than any you could obtain with plant fibers.

Animal fibers must be treated carefully during the dyeing process. Cooking time is shorter than for vegetable fibers.

Yarns should be simmered in the dye solution, not boiled, and should be handled as little as possible when wet. Turn them over gently in the water to keep them from settling to the bottom of the pot and avoid wringing or twisting them.

Wool will shrink if subjected to abrupt temperature changes. Always immerse it in room-temperature water, then raise the temperature slowly, allowing at least half an hour to reach a simmer. Be sure that dye and mordant baths are the same temperature if you move yarn from one to another.

Plant fibers such as cotton and linen do not absorb color easily and must be scoured and mordanted at higher temperatures and for longer periods than those from animals. They must then be boiled for as long as one to two hours in the dyebath. Grasses can also be dyed but must be treated gently. To minimize handling, mordant and dye them in the same bath.

Yarn is the easiest textile to dye since slight unevenness of color is unnoticeable. To keep yarns from tangling during dyeing, loop them into skeins, then tie the skeins with string at various points. Make the ties very loose so that dyes and mordants can reach the yarn. To store yarn between steps, you may either wrap it wet in a towel and keep it for a day or two (or for as much as a week if refrigerated) or dry it and keep it indefinitely. To dry, gently squeeze out excess moisture, then hang the skeins. Turn the yarn several times during the drying so that it will dry evenly. Before immersing dry fibers in a mordant or dye, rewet them in clear water to promote deep, even penetration.

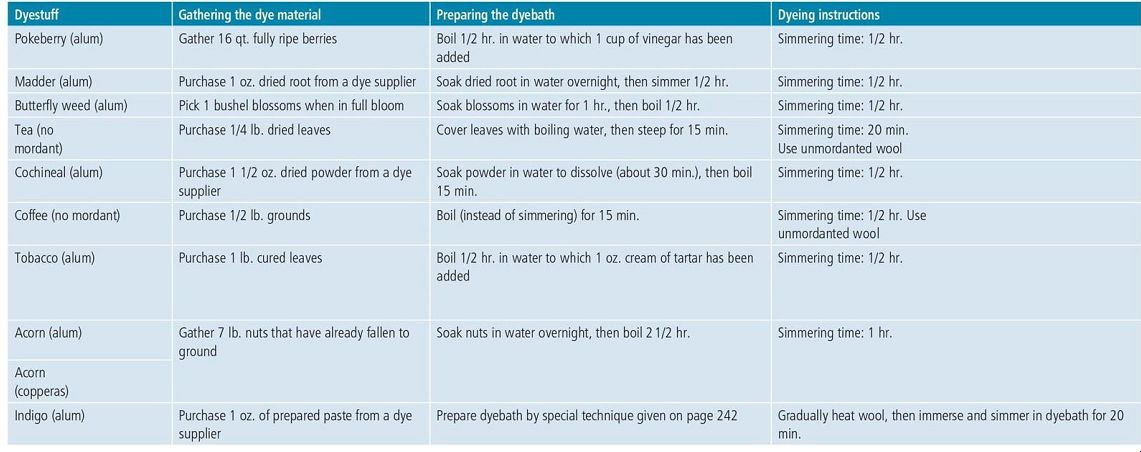

No two dye-baths made from natural dyes are quite the same. Colors made from identical plants will vary according to when and where they were collected, the chemistry of the water in which they were cooked, and even the weather conditions during their growing season. The chart gives formulas and cooking times for a variety of colors from several popular, widely available dye materials. While these recipes provide good guidelines, the colors you create will be your own and, as you gain experience, you will enjoy experimenting with other recipes.

Sources and resources

Books and pamphlets:

Adrosko, Rita J. Natural Dyes and Home Dyeing. New York: Dover, 1971.

Bemiss, Elijah. The Dyer's Companion. New York: Dover, 1973.

Dye Plants and Dyeing. Portland, Oreg.: Timber Press, 1994.

------

-----------

===