The customer is the immediate jewel of our souls. Him we flatter, him we feast, compliment, vote for, and will not contradict. (Ralph Waldo Emerson)

Introduction

The term 'logistics' comes from militaristic roots and is not readily associated with the non-tangible notion of 'customer service'. And yet, customer service represents the output of a firm's business logistics system and the physical distribution or 'place' component of its marketing mix. Thus, customer service is the interface between logistics activities and the demand creation process of marketing, and measures how well a logistics system functions in creating time and place utility for customers.

Initially, physical distribution or logistics and marketing were linked; early writings in marketing related to distributive trade practices due to the increasing significance of 'middlemen' who were performing more functions between producers and consumers (Weld, 1915). Middleman specialization included activities still prevalent today, such as assembling, storing, risk bearing, financing, rearranging, selling and transporting.

Such activities provide place and time utility, i.e. products in the right place through movement and at the right time through availability. Conversely, manufacturing provides form utility of goods through making tangible products from raw materials, while other marketing activities such as credit and quantity discounts provide possession utility. The operative instrument for such middlemen is the channel of distribution.

A disintegration or segregation of physical distribution from the other three marketing mix variables of product, price and promotion began in the 1950s with the introduction of the marketing concept. Physical distribution activities were reduced to only physical supply and distribution functions and the notion of physical distribution customer service was misplaced.

However, a move to reintegrate physical distribution and marketing began in the 1970s when writers argued they belonged together in terms of theoretical progress and applications owing to their strong historical linkages and conceptual developments. Such a rediscovery stemmed from the need to focus on customers in a changing environment and the realization that firms that did so would obtain additional business and profits from leveraging their distribution operations.

Further, customers have become more sophisticated and demanding during the past 30 years and their expectations of suppliers' abilities to meet their needs have subsequently increased. Accordingly, many sup pliers, retailers and service organizations have striven to improve logistics customer service processes to establish or maintain a competitive advantage. Desired outcomes are satisfied customers, increased customer loyalty, repeat and increased purchases, and improved corporate financial performance.

But what exactly is customer service, particularly in a logistics or supply chain context? Johns (1999) noted there are 30 definitions for the word 'service' in the dictionary; thus the concept of service in a business context may be elusive or confusing. Service can mean an industry or organization (e.g. government services), an outcome that has different perspectives for both service provider and customer (e.g. on-time delivery), product support (e.g. after-sales service) or an act or process (Johns, 1999).

La Londe and Zinszer initiated a refocus on logistics customer service with their major study, Customer Service: Meaning and measurement, published in 1976. Their definition of logistics customer service was presented as:

a process which takes place between buyer, seller and third party. The process results in a value added to the product or service exchanged. … the value added is also shared, in that each of the parties to the transaction or contract is better off at the completion of the transaction than they were before the transaction took place. Thus, in a process view: Customer service is a process for providing significant value-added benefits to the supply chain in a cost effective way. The notion of process suggests that logistics activities are more like services than goods. There are distinct differences between services and goods within the marketing mix category of product and Hoffman and Bateson describe the four important characteristics that distinguish services from goods as:

intangibility as services cannot be seen, smelt, felt, tasted or otherwise sensed similar to goods; inseparability of production and consumption as most services involve the customer in the production function; heterogeneity or inconsistency of the service from the perspective of the service delivery and customer experience; and perishability of the service if it is not consumed at the moment in time it takes place, i.e. the service cannot be inventoried. Primary logistics activities include transportation, warehousing, inventory management and order processing, and usually do not physically trans form or affect goods. Logistics activities can certainly be heterogeneous, e.g. order cycle time variability and consistency, and are also intangible e.g. the storage or delivery of a good, and perishable, e.g. a lorry leaving on its delivery route.

What is less clear is how inseparable logistics activities are as regards the customer. The customer is involved in the ordering and receiving stages but is relatively passive throughout the provision of the logistics activities, provided the variability is within accepted bounds.

Nevertheless, logistics activities generally encompass characteristics and classification of services, i.e. benefits received by a customer such as time, place and possession utilities are provided by way of a service or enhanced product offering from logistics activities rather than from attributes of a basic product.

Products and prices are relatively easy for competitors to duplicate.

Promotional efforts also can be matched by competitors, with the possible exception of a well-trained and motivated sales force. A satisfactory service encounter, or favorable complaint resolution, is one important way that a firm can really distinguish itself in the eyes of the customer. Logistics can therefore play a key role in contributing to a firm's competitive advantage by providing excellent customer service.

Thus, application of logistics customer service would be well served by the use of evaluation and analysis concepts and tools from the services marketing area. However, theories and techniques in the marketing discipline have been slow in finding application in logistics research, notwithstanding calls for reintegration with logistics and calls for other interdisciplinary applications in logistics.

The foregoing raises practical questions regarding logistics customer service and its application within firms. For example, what is the state of play in logistics customer service today? What are important elements of logistics customer service? And how can firms establish appropriate customer service strategies and policies? These issues are explored in the following sections.

Logistics Customer Service

Today Firms attempt to meet various shareholder / stakeholder requirements in the ordinary course of their business. Profitability, calculated from sales revenue (or turnover) minus expenses, is one of those requirements and is by no means assured for those firms that do not consider both factors carefully. Without profits, shareholder capital and retained profits will erode and bankruptcy might result.

Logistics costs such as inventory, warehousing, transportation and in formation / order processing comprise a firm's expenditure on customer service. Further, the objective for the firm is to maximize profits and minimize total logistics costs over the long term, while maintaining or increasing customer service levels. Such an objective might be considered a 'mission impossible' and firms must carefully choose among the various trade-offs to satisfy customers' needs and maximize profits while minimizing total costs and not wasting scarce marketing-mix resources. Thus, there is a necessity to evaluate trade-offs between determining / providing additional customer service features sought by customers and the costs incurred to do so.

However, customer service levels may be higher than a customer would set them and firms should 'banish the costly misconception that all customers seek or need improved service'. However, choosing when to meet and when to exceed customer expectations is a key factor. Not all service features are equally important to each customer, and most customers will accept a relatively wide range of performance in any given service dimension.

Further, most firms in the supply chain do not sell exclusively to end users. Instead, they sell to other intermediaries who in turn may or may not sell to the final customer. For this reason, it may be difficult for these firms to assess the impact of customer service failures, such as stock-outs, on end users. For example, an out-of-stock situation at a manufacturer's warehouse does not necessarily mean an out-of-stock product at the retail level. However, the impact of stock-outs on the customer's behavior is important.

Recent research has found that an average out-of-stock rate for fast moving consumer goods retailers across the world is 8.3 percent, or an average on-shelf availability of 91.7 percent. Consumer responses to stock-outs were: buy the item at another store (31 percent), substitute a different brand (26 percent), substitute the same brand (19 percent), delay their purchase until the item became available (15 percent) and do not purchase any item (9 percent). Thus, 55 percent of consumers will not purchase an item at the retail store while 50 percent of consumers will substitute or not purchase the manufacturer's item.

One way to establish a desirable customer service level at the retail level is to take into account such consumer responses to stock-outs. When a manufacturer is aware of the implications of stock-outs at the retail level, it can make adjustments in order cycle times, fill rates, transportation options, and other strategies that will result in higher levels of product availability in retail stores.

These observations reinforce the notion that firms must adopt a customer oriented view and seek out customer needs. Firms also have to ask customers the right questions to ensure that important and relevant criteria are captured. For example, one food manufacturer maintained a 98 percent service level, which necessitated large inventories in many warehouse locations. However, this practice often resulted in shipping dated merchandise and customers therefore perceived this practice as evidence of low quality and poor service.

Quality in logistics means meeting agreed-to customer requirements and expectations. Suppliers need to develop and deliver service offerings more quickly in the light of the many changes to distribution that have emerged, such as technological advances of efficient consumer response and just-in-time delivery. However, the notion of pleasing the customer at every turn regardless of cost has undergone a re-evaluation such that suppliers or shippers are now attempting to accommodate customers while optimizing the supply chain.

This tactic requires suppliers to negotiate with the customer and possibly cost-share with other actors in the supply chain. Such negotiations may be difficult to implement as there is little evidence that logisticians and suppliers have developed sufficient customer interest in logistics activities. This may be indicative of suppliers not properly determining customer needs when they establish customer service policies and trade-offs.

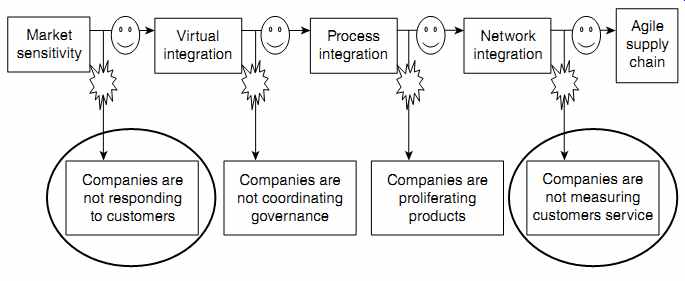

Despite 30 years of research and application of logistics customer service, this attitude still appears to be the case. Van Hoek, in Section 6 of this guide, examines barriers to establishing an agile supply chain and argues that many firms are not considering the customer's point of view, nor are they measuring customer service in a meaningful way. FIG. 1 presents these 'pitfalls' relative to flows in an agile supply chain.

The foregoing suggests that a customer's product and service needs, and their subsequent supplier selection criteria for logistics services, extend beyond usual business-to-business criteria such as product quality, technical competence and competitive prices. Customer evaluation of logistics suppliers may include a number of intangible factors related to the service being provided as the customer seeks added value or utility from it.

An example is whether customer service representatives are on call 24 hours a day. A firm must therefore have the ability to recognize and respond to customer needs if it is to have any chance of satisfying them and achieving the benefits of loyalty and profitability. But to do that it must initially determine what the customers' needs are, both from its own perspective and from that of the customers. The next section discusses possible elements of logistics customer service.

================

FIG. 1 Pitfalls in logistics customer service.

Virtual integration Market sensitivity Companies are not responding to customers Process integration Network integration Agile supply chain Companies are not coordinating governance Companies are proliferating products Companies are not measuring customers service

===============

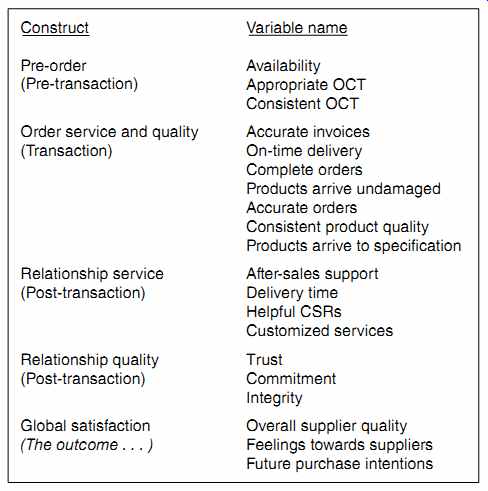

FIG. 2 Elements of logistics customer service and relationships Source:

Grant, 2004, p 191

[Construct

Pre-order (Pre-transaction) Order service and quality (Transaction) Relationship service (Post-transaction) Relationship quality (Post-transaction) Global satisfaction (The outcome ...)]

[Variable name

Availability Appropriate OCT Consistent OCT Accurate invoices On-time delivery Complete orders Products arrive undamaged Accurate orders Consistent product quality Products arrive to specification After-sales support Delivery time Helpful CSRs Customized services Trust Commitment Integrity Overall supplier quality Feelings towards suppliers Future purchase intentions]

=============

Elements of Logistics Customer Service

A first step in understanding a customer's service requirements or needs is to audit existing customer service policies. This will allow the firm to see what they presently offer and determine how important employees believe these logistics customer service elements are to customers. Difference industrial sectors will, of course, have different emphases regarding such elements; however, the basic groupings should be similar.

La Londe and Zinszer (1976) proposed that logistics customer service contains three distinct constructs: pre-transaction, transaction and post- transaction, which reflect the temporal nature of a service experience. La Londe and Zinszer's work was conducted 30 years ago and a more recent study from the customer's perspective, as opposed to the supplier's perspective, found similar constructs of logistics customer service.

However, Grant's work found that the post-transaction construct also includes elements of relationships; his entire set of variables related to the three constructs is shown in FIG. 2.

Firms can use this list of elements to develop their own customer service features; this list is by no means exhaustive but does provide an appropriate starting point for firms to develop logistics customer service strategies.

Firms will likely have to add or delete some elements to service their own sectoral and local requirements.

These two studies also confirm that firms should categorize customer service elements into dimensions related to pre-transaction, transaction and post-transaction events when facilitating operations design and customer service planning. This categorization will enable firms to determine critical events in their service and allow them to monitor and follow up on service failures, as will be discussed in the next section.

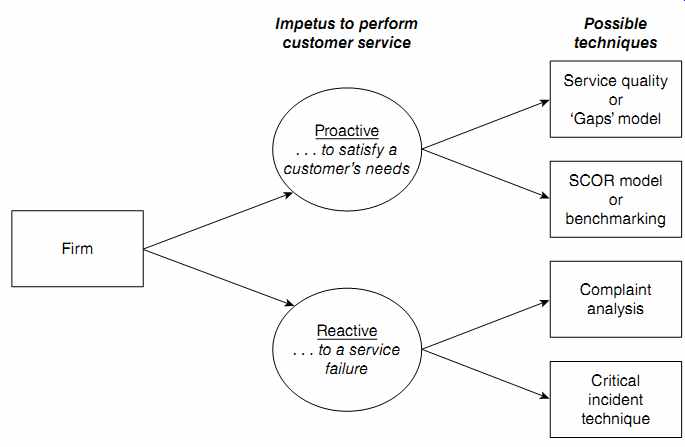

FIG. 3 Customer service strategy process

Strategies For Logistics Customer Service

The impetus to develop a logistics customer service strategy can be either proactive, reactive or a combination of both. A proactive impetus follows from a firm's desire to satisfy its customers' needs, while a reactive impetus results from a service failure. FIG. 3 illustrates this dichotomy and presents possible customer service techniques related to each impetus.

Reactive techniques Understanding and obtaining information about customer requirements necessitates an exchange of information between customers and firms.

Complaint analysis is one such exchange, concerning perceived customer dissatisfaction resulting from a customer service experience or critical incident.

Complaints derive from a 'moment of truth' between supplier and customer that is considered a critical incident. Critical incidents are defined in psychology as 'any observable human activity that is sufficiently complete in itself to permit inferences and predictions to be made about the person performing the act. To be critical, an incident must occur in a situation where the purpose or intent of the act seems fairly clear to the observer and where its consequences are sufficiently definite to leave little doubt concerning the effects'. Thus, a critical incident is a moment of truth that becomes representative in the mind of a customer .

The critical incident technique (CIT) was developed as a process to investigate human behavior and facilitate its practical usefulness for solving practical problems. CIT procedures consist of collecting and analyzing qualitative data to investigate and understand facts behind an incident or series of incidents. Some uses of CIT applicable to business include training, equipment design, operating procedures, and measurement of performance criteria or proficiency.

Complaint handling is significantly associated with both trust and commitment. These concepts are important for supplier-customer relationship development. Complaint analysis thus has a role as part of a post-transaction process but is not a complete form of information for firms when used in isolation.

Such information does not provide an understanding about what customer service features actually provide customer satisfaction. Thus, while it 'might be an effective way to fix yesterday's problems' it is 'a poor way to determine today's (or tomorrow's) customer requirements'.

Complaint analysis has also been called a defensive strategy since its focus is directed at aggressively protecting existing customers rather than searching for new ones. Therefore, firms using only complaint analysis or CIT techniques might find it difficult to determine current and future success factors and establish a competitive advantage.

Proactive techniques

It is important that a firm establish customer service policies that are based on customer requirements and that are supportive of the overall marketing strategy. What is the point of manufacturing a great product, pricing it competitively and promoting it well, if it is not readily available to the consumer? At the same time, customer service policies should be cost- efficient, contributing favorably to the firm's overall profitability. A proactive customer service strategy allows a firm to consider all these factors.

One popular method for setting customer service levels is to benchmark a competitor's customer service performance. One major question is what to benchmark, and the Supply Chain Council's supply chain operations reference (SCOR) model provides a framework to analyze internal processes

-+ plan, source, make, deliver and return.

There are several issues about the effectiveness of benchmarking, for example it may promote imitation rather than innovation, best practice operators may refuse to participate in any benchmarking exercise, it focuses on particular activities and thus there is a failure to allow for inter-activity trade-offs, and there is difficulty in finding well-matched comparators.

Further, while it may be interesting to see what the competition is doing, this information has limited usefulness. In terms of what the customer requires, how does the firm know if the competition is focusing on the right customer service elements? Therefore, competitive benchmarking alone is insufficient. Competitive benchmarking should be performed in conjunction with customer surveys that measure the importance of various customer service elements.

Opportunities to close differences between customer requirements and the firm's performance can be identified and the firm can then target primary customers of competitors and protect its own key accounts from potential competitor inroads. The service quality model developed from the services marketing discipline and presented in the next sub-section enables a firm to identify such differences and follows the call to use more interdisciplinary techniques in logistics customer service.

The service quality model

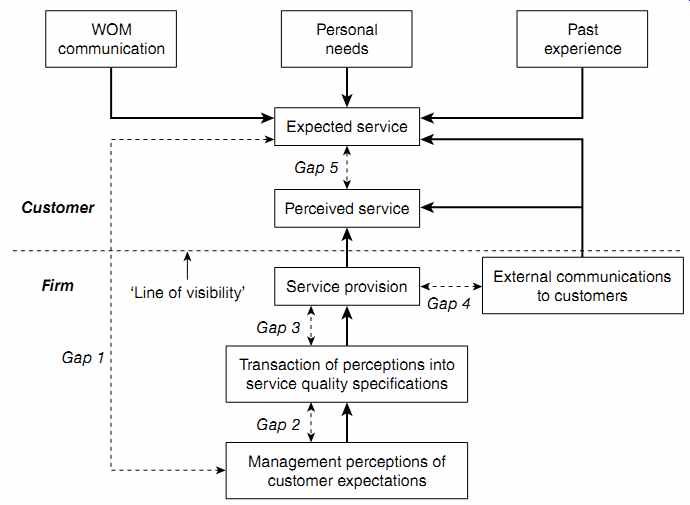

Customers evaluate services differently from goods owing to their different characteristics. One popular method to investigate such evaluations is the service quality or 'gaps' model. Customers develop a priori expectations of a service based on several criteria such as previous experience, word-of-mouth recommendations, or advertising and communication by the service provider.

Once customers 'experience' a service they compare their perceptions of that experience to their expectations. If their perceptions meet or exceed their expectations they are satisfied; conversely, if perceptions do not meet expectations they are dissatisfied. The difference between expectations and perceptions forms the major 'gap' that is of interest to firms.

FIG. 4 presents this model and includes the customer's and firm's positions. The expectations and perceptions 'gap' is affected by four other 'gaps' related to the firm's customer service and service quality activities which are for the most part invisible to the customer.

FIG. 4 Service quality or 'gaps' model.

First, the firm must understand the customer's expectations for the service. Gap 1 is the discrepancy between consumer expectations and the firm's perception of these expectations. Second, the firm must then turn the customer's expectations into tangible service specifications. Gap 2 is the discrepancy between the firm's perceptions of consumer expectations and the firm's establishment of service quality specifications.

Third, the firm must actually provide the service according to those specifications. Gap 3 is the discrepancy between the firm's establishment of service quality specifications and its actual service provision. Last, the firm must communicate its intentions and actions to the customer. Gap 4 is the discrepancy between the firm's actual service provision and external communications about the service to customers.

Gap 5 is associated with a customer's expectations for a service experience compared with its perceptions of the actual event, and is the sum of the four gaps associated with the firm, i.e. Gap 5 = (Gap 1 + Gap 2 + Gap 3 + Gap 4). The firm must minimize or eliminate each discrepancy or gap that it has control over in order to minimize or eliminate the customer's discrepancy or gap related to the service experience. Using the service quality model forces a firm to examine what customer service and service quality they provide to customers in a customer-centric framework.

An Example from Online Retailing

During the past decade the internet has created a retail and consumer revolution by providing a new, convenient channel for shopping. The online retail market is growing rapidly and now covers a large assortment of products and services. Throughout this period, retailers have had to ensure that they offer consumers appropriate customer service and a pleasant online shopping experience, including the order fulfillment process.

The responsibility of many physical aspects of the fulfillment process, which previously lay with the consumer in-store and beyond, is now taken on by the retailer. This final extension to the usual definitions of logistics management from 'point of origin to point of consumption' is referred to as the 'last mile' process and means that greater complexity now attaches to a retailer's distribution system. This has major implications for a retailer as the efficient management of distribution and fulfillment in the 'last mile' can reduce costs, enhance profitability and thus provide competitive advantage.

Online retailing of physical products accounts for two-thirds of total online sales in the UK (Internet Measurement Research Group, 2008). These online purchases involve the handling and transferring of physical products, i.e. packing, picking, dispatching, delivering, collecting and re turning. Further, a product purchased online or 'virtually' cannot be used by the consumer until it is delivered to him or her at the right place, at the right time, in the right quantities and in the right condition.

Thus, from a consumers' perspective, fulfillment is generally considered to be of the utmost importance and a crucial attribute affecting their judgment of service quality and satisfaction. Further, fulfillment has been identified as a main challenge facing internet retailers and a major barrier preventing consumers from purchasing online.

Xing and Grant (2006) developed an electronic physical distribution service quality (e-PDSQ) framework from the consumer's perspective that addresses the foregoing issues facing retailers who sell on the internet.

The framework consists of four constructs - availability, timeliness, condition and return, and related variables - as shown in Table 7.1.

==============

Table 1 E-PDSQ framework constructs and variables

Constructs

Timeliness (T) Availability (A) Condition (C) Return (R)

Variables

Choice of delivery date; Choice of delivery time slot; Deliver on the first date arranged; Deliver within specified time slot; Can deliver quickly

Confirmation of availability; Substitute or alternative offer; Order tracking and tracing system; Waiting time in case of out-of-stock situation

Order accuracy; Order completeness; Order damage in-transit

Ease of return and return channels options; Promptness of collection; Promptness of replacement

==============

This e-PDSQ framework was empirically tested in a survey of online consumers in Edinburgh, Scotland and confirmed the framework's appropriateness. Price was the most important online purchasing criterion, which suggests it is the principal motivator in the online market and that the market is getting more price-transparent with consumers who are becoming more price-sensitive.

The five variables most important to consumers in an online delivery context were: order condition, reflecting its role in demonstrating a retailer's reliability; order accuracy, considered important for repeat business; order confirmation, which demonstrates consumers' unwillingness to wait and their intolerance with stock-outs; and easy return and prompt replacement, which reflect consumers' concerns over product returns.

The Xing and Grant study provided a parsimonious set of e-PDSQ variables and constructs for retailers to use to design and operate their online offerings, based on the Parasuraman et al's (1985) service quality model, and thus demonstrates how firms can adapt and use models and ideas from other disciplines to provide effective customer service in a logistics context.

Summary

Customer service is a necessary requirement in logistics activities and is affected by various environmental factors shaping today's marketplace.

Logistics customer service has its roots in the marketing discipline and logisticians can use and learn from marketing techniques and methodologies to investigate customer service.

A strategy for logistics customer service requires a basic trade-off between costs incurred and enhanced profit received. Each industrial sector will also have its own unique needs and issues that further complicate such considerations. However, while the importance of individual customer service elements varies among firms, there is a common set of elements presented above that should provide a useful starting point for most firms.

A global perspective focuses on seeking common market demands worldwide rather than cutting up world markets and treating them as separate entities with very different product needs. However, different parts of the world have different customer service needs such as information availability, order completeness, and expected lead times. Local infra structure, communications and time differences may make it impossible to achieve high levels of customer service. Also, management styles in different global markets may be different from those prevalent in the firm's 'home' environment.

Although customer service may represent the best opportunity for a firm to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage, many firms still do not implement logistics customer service strategies, or do so by simply duplicating those implemented by competitors. The service quality frame work discussed above can be used by firms to collect and analyze customer information, determine what is really important to customers, and thus enhance their customer service initiatives. Globally, customer services provided by the firm should match local customer needs and expectations to the greatest degree possible. A successful output of such customer service considerations will be a satisfied customer, which should lead to increased profitability for the firm.

PREV. | NEXT

top of page Home Similar Articles