Low-Maintenance Landscape: The Lawn

|

Researchers at the national lawn care service headquartered in Worthington, Ohio, tell about a strain of Zoysia grass, discovered in an Asian cemetery, that doesn’t need mowing. Certain strains of Zoysia, vigorously promoted these last ten years, stay presentable with only two mowings per year, or so proponents claim. Meanwhile, work continues on using hormones to control grass growth, hopefully to cut down on the homeowner’s mowing chores. All this sounds like good news except to lawn mower manufacturers. But if I were selling mowers, I wouldn’t be too worried. The evidence suggests that more people like to mow than hate the job, and the best proof of that is the way homeowners continue to mow much more than necessary, both in area and frequency. My mother’s favorite job was mowing—after she got a riding mower. In the midst of raising a large family, she said that the time on her mower was peaceful and meditative, the noise of the motor insulating her from the world. Many other people tell me the same thing. Or demonstrate it by their actions. The retired farmer down the road keeps his lawn carpet neat, but that is not enough. About three years ago, he began to mow the roadside ditch in front of his property. Little by little, he extended the mowed area along the road in both directions. By the end of last summer he was mowing a quarter mile in both directions. With the call of the open road beckoning him on, he may push his mowing frontier this year as far as a tank of gas will take him. Maybe he will carry gas and refuel along the way, eventually crossing the country with the first transcontinental swath of mow grass. Cutting grass in America provides the same outlet that the motorcycle does for the Easy Rider. What people want is not a low maintenance lawn, but a no-maintenance mower. Another common mowing personality might be called Super-neat. Super-neat says he hates mowing and would rather be golfing, but his actions belie his words. He mows even when it is almost impossible to tell the cut portion from the uncut. So long as one dandelion sticks its fuzzy head above the rug-like surface of his lawn, Super-neat will not rest. Low-maintenance lawn care provides no comfort either for those people fixated by the Lord-of-the-Manor tradition rooted in eighteenth- century Europe: as the size of one’s castle increases, so must the size of the lawn roundabout. And the real proof of your medieval wealth was that you didn’t have to graze livestock on that grass, either. This may be a fine status symbol for the rich, who can pay others to do the work, but pity the rest of us who wish to appear equally as successful but must keep up the appearances by the sweat of our own brows. It is nice to be Lord-of-the-Manor only if you do not have to be Peasant-of-the-Manor, also. Meadow Lawns If you want a low-maintenance lawn the first thing you should do is keep it small—or at least keep small that portion that you regularly mow. On a larger lawn, consider maintaining some of it in a meadow, about 6 inches high, to be clipped twice or thrice a year the way a farmer does a pasture field. (A sickle-bar mower attachment works better for this operation than a rotary blade.) You will open up a whole world of nature to your eyes, in addition to cutting down on your work. The meadow provides a habitat for ground-nesting birds—chipping sparrow, field sparrow, meadowlark, bobolink, and quail to name a few—and a safe harbor for many beneficial animals like toads. Moles can tunnel there in pursuit of Japanese beetle larvae and no one will ever know. The taller grass will hide their tunnels. You can call your meadow a wildflower garden or a butterfly garden since it will become both. You can either let nature provide you with an assortment of weedy wildflowers or plant the ones you like best. One favorite is a milkweed with bright orange blossoms, often called butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa). (In this section, as well as sections 8 and 9, 1 give botanical names only for those plants that I want to distinguish from others similar to it, or for plants that are quite uncommon. Those plants not followed by a botanical name are the common plants most all of us have heard of.) All the milkweeds draw butterflies, the monarch particularly, and many other interesting insects, but the other kinds tend to spread too fast. One of our neighbors decided there had to be a better way than twice a-week mowing. She hired a farmer to tear up half her lawn with a disc. This takes some nerve, since the Superneats will disapprove, but we still live in a free part of America where there is no stupid law to keep us from planting our yards to something besides grass. (However, some towns and cities prohibit the growing of anything but neat ground covers and grasses in the front yard, and others have ordinances that require homeowners to mow regularly, which makes wildflower lawns virtually impossible; flowers never have a chance to bloom and reseed themselves.) This neighbor of ours scattered wildflower seeds over the tom-up sod and waited. By summer, the former lawn was a riot of color and became a showplace of sorts, as people from all over the county drove by to see what That-Lady-Who-Won’t-Mow was going to do next. “It’s worked so well,” she says after two years, “that I wish I had torn up the whole lawn.” Then she laughs. “One day I looked out the window and there was a stranger picking the flowers. I rushed out and explained that she was trespassing on my lawn. The woman looked at me in great astonishment. ‘But it isn’t mowed she said It could only happen in America. Wildflower lawns will not necessarily keep an ideal balance between the various desirable grasses and wildflowers. Our neighbor pulls thistles and wild carrot (Queen Anne’s lace) and such weedy flowers that will overwhelm the others if given a chance. “But it takes less time than mowing,” she says, “is cheaper, and is something I can do with my children. You can’t mow with them, that’s for sure.” A natural meadow can be clipped to control unwanted weeds and tree seedlings the way a farmer clips pastures two or three times a year. You have little control over what grows or doesn’t grow, except by the timing of the mowing. The idea is to let those plants you wish to grow mature before clipping and clip those you wish to keep from spreading before they go to seed. This is not easily done since the desirable and undesirable often go to seed at the same time. Patch mowing—clipping a clump here and a clump there as necessary—is one alternative, but a high-maintenance one. Rotating the natural meadow with a conventional lawn is an easier way. The meadow is allowed to grow as it will for three to five years, with a clipping in July and another in August. Then for two years, the meadow is mowed as a conventional lawn. There are no set rules for the length of the rotation since very little experimentation has been done with this kind of landscaping. You have to proceed by trial and error. Climate can greatly affect the methodology. For example, in drier parts of the West, where there are prairie grasses instead of forest, tree seedlings would not be a problem, so that the prairie lawn need not be clipped or rotated with conventional lawn to stabilize it. If you are familiar with the Flint Hills of Kansas, you know what I mean. Ground Covers A more practical way to cut down on mowing, or at least one that is more socially acceptable, is to replace lawn with low-maintenance ground covers. Three of the better ones are creeping euonymus for sunny places, and pachysandra and myrtle for shady spots. These ground covers, once established, grow thickly enough to shade out weeds (except for an occasional intruder or tree seedling), and they need pruning only rarely, if ever. They are particularly practical in areas difficult to mow—under trees where grass won’t grow very well anyway, or on hillsides where mowing can be hazardous. Lane Palmer, the editor of Farm Journal magazine, a man who knows his way around plants, has been maintaining an euonymus lawn since 1956 at his suburban Philadelphia home. The Palmers’ lot breaks away steeply to the street on two sides, creating an area that is dangerous to mow. With some clippings he was given by a grounds keeper pruning in Independence Square, Palmer started rooting Euonymus radicans coloratus in flats. At the rate of about 50 to 75 square feet per year, he transplanted the rooted cuttings to the problem hillside. The reason for doing only a little bit at a time was that for the first two years the new plantings had to be hand-weeded. After that time, they grew thick enough to shade out the competition on their own. Propagating Ground covers root easily, so you can propagate your own if you want to save money by not buying plants. Cut healthy sprigs about 6 inches long off the ends of growing vines. Pinch off all but the top three or four leaves. Stick the cuttings in a bedding mixture—about half peat and half sand works fine. The mixture should be thoroughly soaked. Dip the base of each cutting in a rooting hormone before inserting it in the soil. (Rootone is a commonly available brand.) Cover the flat of cuttings with plastic film to keep the environment moist around the cuttings. Most of the cuttings will grow roots and will be ready to transplant in about a month. Planting Before setting out the ground cover, the sod should be killed. Palmer used a chemical, but cultivation or a thick blanket of leaves put down well before setting out the transplants will suffice. Palmer says he had his best luck planting the ground cover in September after a good soaking rain, so the sod killing should be carried out in summer. The easiest way to plant the cuttings is to open a slit in the soil with a trowel, slip a cutting in behind the blade, remove the trowel, and tamp the soil firmly against the cutting’s roots. Set cuttings 6 inches apart in both directions to ensure good coverage in one year. At 12-inch spacings, you save on cuttings but have to hand weed for two years. Euonymus is subject to a scale that can usually be controlled with a dormant oil spray in early spring. Occasionally, Palmer has followed up with a malathion spray in May. If you don’t want to use such chemicals, you can prune the old infected plants close to the ground with a power hedge trimmer. Scale affects only old wood. The new growth will come up healthy and will cover the ground effectively in a month. “If that all sounds like a lot of work,” says Palmer, “I can assure you it is only a fraction of the work of mowing and grass care. And the euonymus looks attractive all winter long.” He grows pachysandra (Pachysandra terminalis) the same way, but only in shady areas where it grows best. Palmer says pachysandra requires even less maintenance than euonymus. He likes to plant it under and around trees where it grows much better than grass and where it relieves him of the necessity of mowing close to trees, which carries the risk of scraping the bark of the trunks and getting a twig in the eye. Pachysandra is not very hardy from the colder parts of zone 5 on north. (See the zone map in section 8.) As an alternative in the Midwest, myrtle (ymca minor) with its purple-blue flowers is a traditional choice. English ivy works okay too. Don’t let it have free reign up the side of your house or trees. It can eventually kill a tree, weaken the mortar between stones and bricks, and pull the shingles off your roof. Mulches Bark, wood chips, gravel, rocks, and other inert materials make excellent low-maintenance ground covers for small areas. Grass and weeds will eventually work through, but a layer of black plastic film with holes punched in for drainage, laid down before the ground-cover mulch is applied, will considerably lessen the grass- and weed-pulling work. Around tree trunks and along ornamental borders, such ground covers not only shorten mowing time, but also save the inevitable wounds to plants that mowers cause. One of the most attractive and inexpensive ground covers is pine cones. At a residence I was visiting recently, a corner nook along the house beside the entrance door was covered with various sizes of cones raked from the yard, with dwarf flowers set into the mulch, under laid with black plastic. The cones will last several years—if the squirrels don’t carry them away. Pine needles also make an attractive mulch. They are abundant under larger white pine trees. In addition to old standbys like buckwheat hulls, bagasse, salt hay, peat moss, and shredded bark, you may find you have access to corncobs, rice hulls, shavings from power wood planers, shredded cornstalks, ground seashells, or oyster shells (in the South), peanut hulls, or broken shards of brick or pottery or clay tile (around factories). All kinds of possibilities offer themselves in crushed stone and gravel. I’ve seen smooth stones up to the size of a fist piled up attractively around big trees to avoid mowing over exposed roots. The disadvantage of using much larger rocks is that they can become even more hazardous to the mower than the gnarled roots they cover. Ordinarily, the purpose of gravel or any inert ground cover is to provide what landscapers call mowing strips, meaning non-mowing strips actually. The ground cover is put down about a foot out from trees, plants, walls, fences, etc., so that you can dream away as you mow and not have to worry about collision courses with your landscape. But obviously, the ground cover must be down even with the mowing surface. Sidewalks and flower borders raised above lawn level are a menace to mowers and a hindrance to low-maintenance mowing, forcing you to make continuous use of an edger.

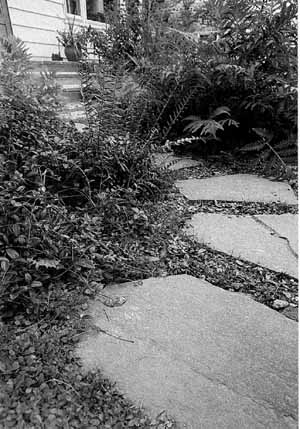

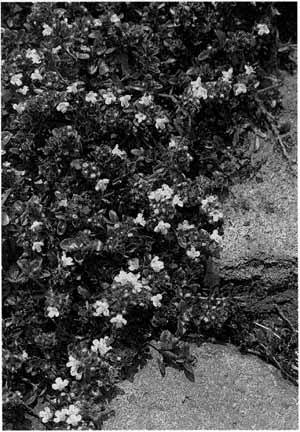

Combining Live Ground Covers and Inert Mulches Sometimes live and inert ground covers can be used in combination with excellent low-maintenance results. A gravel or shredded bark mulch will hold back weeds a long time while ground-cover plants are getting established. Ground-cover plants spread mostly by underground stolons and send up stout new shoots that will penetrate up through the inert ground cover much more readily than weeds. By the time a weed has even thought about rearing its ugly head above the mulch, the ground cover has spread to cover all. This can work well not only for the ground covers already mentioned, but for some you might not have considered. Lily of the valley (Convallaria majalis), for example, spreads thickly by under ground roots and, with the help of a permanent mulch, will out compete weeds most of the time. This works especially well in a partially shaded area where lily of the valley is at home, but many weeds are not. Another slick way to combine two kinds of ground covers for low maintenance is with flagstones and creeping thyme (Thymus serpyllunt) . In this case, the larger the flagstones, the more effective the low maintenance. The stones are laid as for a terrace right on the ground; no underlayment is necessary. And the spaces between the stones are planted to creeping thyme. This plant has one advantage over other ground covers: it will stand heavy human traffic. It is very low growing and will spread out a little over the outer perimeters of the flagstones and eventually keep weeds from growing up between the stones. The effect is one of stepping stones in a “pool” of thyme. As with other ground-cover plants, this one is obviously high maintenance at first, with years of low maintenance to follow.

Other Ground-Cover Suggestions There are other ground-cover plants to consider for special situations. Bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi) is good for cold climates or barren soil high in acidity. Crown vetch (Coronilla varia) serves fairly well on steep and similar problem areas but always appears oversized for small landscapes. Various heaths (Erica carnea, for example) and heathers (Calluna vulgaris) are good for sandy, acid conditions on both coasts. For thy, hot areas like the Southwest, ice plant (Mesembryanthemum ctystallinum) is a popular choice. Finally, a caution. Some low-maintenance ground covers turn out to be very high-maintenance weeds. Honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica) is a great mistake, and if you aren’t choking with it already, don’t plant it. Beware, too, of one of the speedwells (Veronica officinalis), which I have heard referred to as “creeping Charlie” but more often around here as “creeping #$%“&“!“—and you can’t interpret that too foully. This low- growing plant with little bluish flowers is not meant to be a ground cover, but in a lawn it can become that. Speedwell is a good name for it because it will speed well over your whole lawn in a year’s time. Almost all lawns I see in the northeast quarter of the country are overrun with it. If you don’t have it yet, be very careful about transplants taken from a friend’s garden; you may unknowingly bring along a bit of speedwell, too. Actually, it is fairly harmless and remains green no matter how often or low you mow it. But it will force out bluegrass in partly shady areas, if not sunny areas, and run rampant there. Only herbicides can kill it. You can’t get rid of it by tearing up the sod, unless you tear at it for several years. Even then, if one little bit of root remains alive (and it will), within a few years it will take over again. Other Low-Maintenance Alternatives to Lawns Grass itself can be a low-maintenance plant, as we shall see later in this section—certainly better than a rock garden or a peach orchard. But some alternate uses of the yard are less work and expense. A Daisy Field Long before “flower lawns” became popular, Ivan Hill of Tiffin, Ohio, discovered quite by accident that he could maintain his lawn as a “daisy field” as he calls it, with much less mowing. When Shasta daisies (Chrysanthemum maximum) first appeared in his yard years ago, he didn’t have the heart to mow them. Each year the clump grew in size until finally the whole lawn along the street was a waving sea of daisies every May and June. “All I do is just not mow until late in June,” he explains. “I’ve started to plant the whole backyard to daisies, too.” To do so, all he does is sprinkle some mature seed heads on the ground. Nature does the rest. Apparently, daisies have some way (perhaps by a natural herbicide like the oat plant produces) of keeping competition from other weeds at bay because Hill’s “daisy field” is remarkably free of other weedy growth, even though it has been established for years. “And you can’t hurt the daisies by tramping through them. They spring right back up. The neighbors’ kids play ball on that lot.” He pauses, smiles. “They spend most of their time hunting for the ball, though.” The Hills have given away many bouquets for church and wedding decorations and to passersby who stop to ask. And they have cut mowing time nearly in half. “Tree Lawns” Normally, a good low-maintenance lawn practice is to plant trees and ornamentals in clumps to free up lawn space in one relatively easy area to mow instead of dotting trees and bushes all over the landscape. But Bob and Judy Gucker near McCutchenville, Ohio, are finding freedom from mowing in the opposite ploy. They planted their very large hillside lawn completely to evergreen trees at b-by-b-foot spacings. That was 11 years ago. For the first couple of years, mowing around the little trees was a difficult job, but the Guckers were young and able. (We’re talking about over 400 trees, counting the side yard.) Now the trees have filled in most of the lawn space, with only quiet, lush hallways of grass remaining. Within 2 or 3 more years what had once been a large, tedious mowing job will be no mowing job at all. There have been other advantages. Bird life has increased remark ably, to the delight of the Guckers who are avid bird-watchers. The “tree lawn” has become a very effective windbreaker for their hilltop house and also acts as natural air-conditioning, thanks to the breezes that filter through. The Guckers have never needed to buy an air conditioner. “And the tree lawn makes a marvelous place for children to play,” says Judy. “We always had a hard time with parties, getting the kids to come in the house. They wanted to play hide-and-seek out there all night.” Low-Maintenance Grass You can make a mistake by ruling out grass entirely from your yard. It is possible to do that with a house in the woods, letting the yard be just a continuation of the forest floor. But that gambit has drawbacks, too (this is the voice of experience speaking). To make it work demands that trees cluster around the house, throwing fairly heavy shade on the ground to inhibit brush, grass, and weedy growth. The subsequent leaf-mold floor is free of weeds and grass, true, and if you have superior botanical knowledge, you can coax it to support some ferns, a moss garden, and a few shade-loving plants. But it will not stand much traffic, and mud and other shoe-clinging debris will find its way into the house. In this situation, lots of decks and walks are necessary, and so one trades one kind of high maintenance (lawns) for another (care of wood decks, etc.). Not to mention that you have to worry about trees falling on the house. What’s more, such woodland houses will invariably have problems with mildew because of minimum sunlight and poor air circulation. The house will smell the way a vacation cabin does that has been closed up too long. A dehumidifier roaring away will only partially solve the problem. Nor is replacing all grass with gravel or (horrors) green cement an advisable alternative. An architect in Chicago once told me that owners of downtown office and apartment buildings had discovered that although pools and fountains and concrete landscaping cost considerably more than grass to install, over the long haul maintenance was cheaper! But this conclusion would hardly ever apply to a residential home. First of all, in the latter case, the space around the house is a part of the living area in a way that is not true of an office building. But more importantly, homeowners in the dry, hot West who gravel or concrete over their entire lawn area have seen their air-conditioning costs rise dramatically. Grass absorbs heat; masonry gets hot and throws it back in your face. The search for the perfect grass will never end, because as scientists develop better ones, human expectations rise still higher. The perfect grass must be a rich dark green. No other color, such as the rich browns of a Texas Bermuda lawn in January, will do, even if it goes better with the color of the house. When nature will not cooperate, you can buy green dyes to spray the lawn (or your Christmas tree), but dyeing the grass has not caught on, even in the South, there being limits to the excesses of even the fussiest homeowner. The perfect grass will, of course, never yellow with any disease; will be drought resistant; will smother out all other plants; will not wear thin under the pounding footsteps of the entire fourth grade playing football on it every day; will give off a harmless odor undetectable to humans, but which drives stray dogs, moles, and mosquitoes into the neighbor’s yard; and will cut easily with a dull mower blade. Drainage In the realm of practicality, the type of grass you choose is not nearly as important as the condition of the soil you wish to grow it in. The absolutely essential ingredient for success is well-drained soil. Grass will not grow well in poorly drained soil. Fertilizer will not become available to grass in poorly drained soil. Diseases can’t be prevented in poorly drained soil. Grading properly lets excess water run off the lawn most of the time, but level lawns, or lawns with even a slight depression or low spots, especially if the soil is a heavy clay, may need to be helped out with drainage tiles. Established city lawns seldom have a drainage problem—or the problem was taken care of years ago. But if you live in the new suburbs, especially in areas with larger lawns underlaid with heavy clay, be fore warned. And you’ll only exacerbate the problem if you let water from the roof and walls of your house spill off into such problem low spots. A line of drainage tile 1 to 2 feet deep through a problem area can usually be hooked to the drain tile that carries water away from the footers of the house foundation. Sometimes the soil surface can be raised with hauled-in topsoil to provide enough surface drainage to alleviate the problem, but this is no good if the new soil only levels the depression or, worse, back-slopes the water towards the house. There are contractors in every community now equipped with the small rotating wheel ditchers, which do a much neater job than a backhoe at a reasonable price. Good Soil Once drainage problems have been solved, next give attention to the pH of your soil—its balance between acidity and alkalinity. Like most plants, grass likes a slightly acid to neutral soil, a pH of 6.0 to 7.0. If the pH is lower (i.e., more acidic), you can raise it with agricultural limestone. If it is higher (i.e., more alkaline), as it might be in the western Plains area, you can lower it with gypsum. Garden stores and farm service businesses in your area have these materials, and lawn service companies are only too eager to advise you and/or test your soil. Do-it-yourself soil testing kits have a litmus paper test you can perform yourself to tell if your soil is very acid or not. If blueberries, rhododendrons, azaleas, and such acid-loving plants grow well in your yard, the soil is no doubt a bit too acid for a good bluegrass lawn. Keep lime away from your blueberries, rhododendrons, and azaleas. It can kill them, as I found out the hard way. Low-Maintenance Lawn Maintenance With drainage and pH taken care of, low-maintenance fertility pro grams are a snap or would be if homeowners would follow them. But low maintenance methods make all the sacred cows of Superneat lawn management bellow in protest. You may need an initial application of some purchased fertilizer, especially where the bulldozer has left a new house with only subsoil to work with, but after the grass is established, none will be needed in most cases, if you follow a simple procedure: Throw away that bagger on your mower. At least throw it away after that first flush of heavy grass growth in spring. Let the grass clippings fall back into the lawn, there to rot away and return to the soil the nutrients that they consumed while growing. Or if you are bound and determined to play Superneat, carry your penchant for hard work one step further. Instead of putting the grass clippings out for the garbage man to haul to the dump (compounding the problem of waste disposal), compost them and then sprinkle the compost back on the lawn. Removing clippings is usually ridiculous from the standpoint of low maintenance. Superneat pumps fertilizer on his lawn and the lawn pumps it right back out again in excessive grass growth. The extra lushness of all that expensive nitrogen attracts various fungal diseases. Statistics say that there would be more than 16 million acres of grass clippings clogging our dumps if we were all as fastidious as the Superneats. Is that sane? John Howard Falk in his study “The Energetics of a Suburban Lawn,” says the energy inputs in water, fertilizer, pesticides, gasoline, and human labor on a typical California lawn amount to 573 kilocalories per square meter. That is more energy than what is expended on a commercial corn crop! Other studies indicate that in some urban areas, there is more chemical residue runoff from lawn acreage than from farm acreage. There may be times when picking up the grass clippings is necessary, primarily on a new lawn just getting established. Excessive clippings could smother new shoot growth, although I hasten to add this could happen only if the soil has been heavily fertilized and watered. Otherwise, some clippings on the new growth actually shade it and protect it in the start-up period, which is why a light straw mulch on a new lawn seeding is a good idea. Also, in dry parts of the nation, clippings will not rot back into the soil nearly as fast as they do in the humid East or South, and so sometimes excess clippings might need to be removed. But here again, the buildup of clippings is most often due to excessive growth instigated by fertilizers and irrigation. People who bag clippings (and especially people who sell baggers) protest that the clippings will contribute to a thatch problem. Actually, clippings are a very minor part of thatch and are not the cause of the problem, if a problem does indeed exist. Thatch consists mainly of incompletely decayed grass roots, stems, and lower leaf sheaths—the ligneous or more woody parts of the grass plants. Thatch problems are the worst with grasses that spread by a thick layer of stoloniferous growth—vinelike shoots that grow more on the soil surface than in the ground. Zoysia is very prone to thatch problems for this reason. Without good contact with dirt, which would speed decay, old stolon and stem growth build up to where the “thatch” acts just like thatch on a roof—on Zoysia it can actually shed water rather than absorb it. On such thick grasses (Bermuda grass and bent grass can sometimes be problematic, too), picking up clippings may be come an aid to thatch control. Because the grass is so thick, the clippings can’t work their way down to the soil quickly to hasten decay. But there are other reasons why thatch is sometimes a problem today but was not years ago—all of them the fault of human fastidiousness, not nature. Having planted very vigorous, dense modern cultivars, which might be advantageous in some respects, the homeowner compounds the disadvantages of these cultivars by fertilizing and watering heavily. Then, quoting from 10,000 Garden Questions Answered by 20 Experts (Doubleday, 1974) “Tissue decomposition can’t keep up with production, especially on stoloniferous turfs where the thatch hardly contacts soil.” Pesticides also can slow down decomposition. Earthworms are an enormous help in thatch control because they actually eat it and at the same time bring soil and thatch in closer contact with each other. The minute piles of earthworm droppings on the lawn surface, which for mysterious reasons are so repulsive to Superneat, are a godsend to the grass. Again I quote from the volume cited above: “When earthworms are eliminated, as with chiordane treatments, thatching generally increases.” Although not very practical for home lawns (it used to be a method used on golf courses), an effective control for thatch is simply to sift weed- free dirt or compost over the grass, which does the same thing that earthworms do better. Instead, Superneat resorts to high technology. He rents a “dethatcher” which tears the hell out of the sod, and of course will only solve the problem temporarily. Or he buys a big spiked drum to pull behind his lawn tractor, which supposedly aerates his soil by punching holes through the thatch. These aerators are miniature versions of the soil compactors used in roadway construction and compact your lawn soil at least as much as they aerate it. Earthworms aerate your soil free of charge and bring up minerals from the subsoil that your grass needs to grow well. A good earthworm population means you will eventually have moles, which are themselves terrific soil aerators. But Superneat, who abhors a mole tunnel, embraces a dethatching machine that renders his lawn twice as ugly as a whole colony of moles. To get rid of moles, his handy-dandy lawn service expert has a standard sales line. Moles eat grubs (another ugh creature) and so to get rid of moles he poisons the grubs. Good logic. Except that he poisons the earthworms, too, and heaven only knows how many other beneficial soil microbes and insects. It is one thing to spray herbicides, which by comparison are not known to be as harmful to humans, but soil insecticides are strong medicine. Recently (1986), a golfer playing a course that had just been sprayed with insecticides, be came ill and died, his skin coming off in layers. The insecticide to which the cause of death was traced was one of the supposedly milder ones. You can imagine the lawsuit that will develop over this strange occurrence. Why risk anything like it on your lawn for what amounts to nothing? IN DEFENSE OF THE POOR MOLE Moles are in fact very beneficial animals. I know of no case where they have ever harmed a human being. Moles eat soil insects. They do not eat your flower bulbs, carrots, and other plants you prize. A mouse running in a mole hole will eat bulbs, but the mouse doesn’t need the mole hole to do it. He can dig his own. A mole tunnel running down your carrot row should be a reason to rejoice. If there are any carrot maggots down there, the mole will be eating them. And his raised tunnel will hardly ever harm the carrots, as I have learned innumerable times. The mole tunnel rising slightly above the lawn is visible because we shave off the grass there with the mower. Of its own accord, the tunnel would settle back after a few rains, and the grass would grow better there than previously. Furthermore, moles are fairly transient. They move through an area eating earthworms, white grubs, webworms (which can damage the sod more than moles), and Japanese beetle grubs, among others. Then they move on, leaving a generally healthier sod that will quickly rejuvenate itself while the moles work on another part of the lawn. Beats a de-thatcher hands down. Having gone through this argument a hundred times, I know that the American homeowner in general is not going to listen. But if you want to save money, achieve low maintenance, and work far less, leave the moles and earthworms alone. You and your lawn really will survive. And either way, the moles will. Another common practice that increases the chance of a mole “crisis” is the incessant watering of lawns, even in the humid East. Moles work where the earthworms linger. The earthworms linger where there’s moisture. In the drier parts of the summer, they descend deeper as the moisture decreases. The moles you think have disappeared after you poisoned them in the spring are usually only working farther down in the ground and so their tunnels aren’t visible. When you sprinkle the lawn in dry weather, you draw worms and moles back up. Since cool-weather grasses, like bluegrass, naturally go dormant in late summer, you are probably wasting water anyway. If you do manage to keep the lawn green, you will also make it more vulnerable to a host of fungal diseases. Hot-weather grasses, like Zoysia, will stay green anyway with little watering until the weather cools, and then they will begin to turn brown no matter how much you water them. As one courageous lawn expert said recently in the Sunday paper garden section, the best low maintenance practice to ensure a green lawn in August in the eastern half of the country is to allow “weeds” to grow in the lawn that will endure mowing (like white clover). In late summer, these “weeds” might be all the green a typical homeowner has going for him and what really is so bad about that? FIND SOMETHING MORE PRODUCTIVE TO BE FUSSY ABOUT The first rule of low-maintenance lawn care is to not be so fussy about grass—and not let fussy people draw you into competing with them. Fussiness is probably therapeutic for the Supemeats—a way to calm their feelings of insecurity—but it should be understood as that, not the standard by which civilization should be judged. I have a close acquaintance who is a Superneat par excellence. He has qualities I admire, and anyway, what would we do without a few Superneats to maintain some kind of order in a chaotic world. He thinks I am crazy because I have occasionally let my front yard grow up and taken a hay crop from it. I think he is crazy because he manicures, and I do mean manicures, about 5 acres of lawn. The extent he will go to in pursuit of the perfect lawn boggles Neatless Souls like me. WHITE CLOVER, VIOLETS, AND OTHER LAWN FLOWERS There is hardly any plant more beneficial to the low-maintenance lawn than white clover, sometimes called Dutch or Little Dutch clover (Trifoliurn repens). It is such a common and ubiquitous plant that in many areas of the United States it will come up of its own accord on any plot of ground that is mowed frequently. It seems to like being mowed and will keep a lawn green except in extreme dry weather. With grass, especially bluegrass, it has worked out an extremely efficient low-maintenance sym biotic partnership. Like all legumes, white clover, with the help of rhizobium bacteria, draws nitrogen from the air and “fixes” it in the soil. The grass, in turn feeds on this nitrogen, grows vigorously, and crowds out most of the clover. Then when the supply of nitrogen has been used up, the grass diminishes and the white clover comes back to flourish again. Unfortunately, Superneat considers white clover to be a lawn evil and he attempts, without much success, to exterminate it. Why he hates white clover is not clear. It is not that white clover draws honeybees (which should be considered a blessing anyway, unless one is seriously allergic to stings). For some reason, the little white blossoms dotting his otherwise immaculately green sward are terribly upsetting to his eye, like pimples are to a teenager. He fights every year the good fight against white clover, damn the cost, damn the herbicidal runoff. From where I was working in a village once, I watched an old lady laboriously patrol her lawn every day with a butcher knife, attacking dandelions. At the end of the week, I congratulated her on her persistence. But she was not happy. “Now I have to start all over again, on the violets,” she moaned. If she ever were unlucky enough to get rid of them, too, there wouldn’t be anything much left growing in her lawn. There is one kind of violet that makes a most delightful lawn flower because it grows very low to the ground and does not compete with grass at all. The bloom is deep purple and very aromatic, but its main advantage is that it blooms very early in spring, about the same time that crocuses do, and has for all practical purposes disappeared by the time you get the lawn mower out. I have found no species listed in the garden encyclopedias that has a description matching this violet, but I have found it both in Pennsylvania and Ohio, growing either in older lawns or along roadsides in very early spring. It transplants very easily into the lawn and then spreads slowly of its own accord. Another inoffensive low-growing flower for lawns, especially shady, moist areas is moneywort (Lysimachia nurrnnularia). This viny plant that grows flat on the ground blooms yellow in early summer. It’s really a ground cover, but does not grow strongly enough to smother out other plants, and it can be mowed regularly. It is a homeowner’s privilege, I guess, to curse dandelions and plantain and hurl at them the full force of chemical technology. Neatless Souls rather enjoy a few dandelions, and mowing provides enough control to hold them in check. The same with quack grass, which is what keeps part of my lawn green in a dry August. But of course, for the Superneats, such behavior is uncivilized. My experience is that no matter which road one follows, we arrive at the same point: more dandelions, more quack grass. The Best and Worst Grasses for Low Maintenance There are seven kinds of grasses conventionally used in lawns, and many, many strains and varieties of each. Dr. Reed Funk, a professor and turf scientist at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey, has developed 50 new grasses in the last 25 years—and he is only one of many involved in this work. Thus it would be presumptuous if not arrogant for any writer, let alone a Neatless Soul like me, to pretend to know which varieties or strains provide the least maintenance work for any particular lawn. However, I am going to be arrogant and presumptuous and state a general rule of thumb few lawn experts will quarrel with: Choose bluegrass as your primary grass wherever it will grow well and rely on other grasses only where it won’t. A brief review of the seven grasses used in lawns will, I think, bear this out. PERENNIAL RYES Perennial rye probably should be rated high on the list of low maintenance lawn grasses. Rye has always been used in cheap grass mixtures, because it pops up quickly and provides some footing while slower germinating grasses get established. But conventional ryegrasses are annuals, short-lived and coarse. When Dr. Funk, mentioned above, developed the first perennial rye (which he called Manhattan because he discovered it in Central Park), it was a sensation. Even better varieties have been developed since then. They start quickly and are not as aggressive as conventional annual ryegrasses. This makes them a good addition to any grass mixture, especially when planted in the fall, when you want to get the ground covered quickly. Perennial rye is a low cost, no-frills grass and will take fairly heavy human traffic. So it sounds like just the thing for low maintenance, and as varieties continue to improve, it may indeed become No. 1 in this category. But right now, keeping perennial rye perennial takes almost as much care as caring for bluegrass—maybe more in some instances—and even then it will not endure as long as bluegrass. Moreover, it does not make as tight a sod as bluegrass for the same amount of maintenance expended and thus is something of an open invitation to excessive weed growth. But definitely this is the grass for a quick lawn. Used alone, sow 6 pounds per 1,000 square feet. FINE FESCUES Of the two very different kinds of fescue planted in lawns, fine fescues of the creeping red or chewings varieties are used in with bluegrass, mainly because they will grow quite well in moderate shade. They will even dominate most bluegrasses there. Since it is fine textured, however; that is no disadvantage. It does not require as much general care as bluegrass, either, doing better with less fertilizer on poorer ground. If planted alone, the rate is about 4 pounds per 1,000 square feet. If planted with bluegrass, make the mix 30 percent fine fescue to approximately 70 percent blue grass, increasing the portion of fescue for shadier lawns to perhaps 50-50. COARSE FESCUES The coarser, broad-leaved fescues have only recently begun to receive attention in lawn mixtures. They are tough and stand wear and tear better than bluegrass. Used in mixtures with bluegrass, they make a lawn hold up better against the constant tramping of feet. They stay green better in late summer than bluegrass, but at this date, they are not nearly ready to replace bluegrasses, if they ever do. Seeding is about 2 pounds per 1,000 square feet. BERMUDA GRASSES Bermuda grass is popular for the hot South. Improved varieties continue to come out. All of them should be mowed frequently to preserve the green color, but they turn brown in winter. The brown lawns I have looked at in Dallas in January seem quite attractive to me—better than the drifted snow lawns I normally have to look at in January back home in Ohio. I have already mentioned the biggest low-maintenance objection to Bermuda grass—its invasiveness into adjacent gardens. In California, homeowners sometimes plant Merion bluegrass and Bermuda grass together to get a year-round green lawn. To each his own. If Merion bluegrass does well there, I say a gardener would be foolish to plant Bermuda grass, too. Better a half year with a dormant bluegrass than a whole year fighting Bermuda grass in the garden. ZOYSIAS No grass has been merchandised in recent years as vigorously as Zoysia. It is rather easily planted with plugs spotted around an existing lawn. It then spreads slowly to cover all—an indication that it too, like Bermuda grass, can be invasive and difficult to keep out of adjacent ornamental plantings, flower borders, and gardens. Zoysia (even the hardier varieties) is generally not too hardy in the colder parts of the North but excellent for heat and drought resistance in the mid-South. Zoysia smothers out much undesirable weed growth without the help of herbicides, but on the other hand, it is sometimes prone to thatch problems. It turns brown with the advent of cool fall weather and greens up late in spring. But brown or green, it makes a soft, resilient footing and does not require as much mowing as other grasses. It’s a good low-maintenance grass where invasiveness is not a problem. Plant plugs about one per every square foot for fast coverage. BLUIEGRASSES Despite all the latest discoveries of other grass varieties, where cool- season grasses grow well, bluegrass is still best for low maintenance, all things considered. You can, of course, manage a bluegrass lawn with very high maintenance—using the bluegrass varieties that need to be coddled with lots of fertilizer, frequent watering, and exacting pH. And then you must endeavor to keep out all other plants. But a mixture of the newer bluegrasses (namely Citation, Glade, Merion, Newport, Park) and old reliable native bluegrasses—even the wild ones that grow unbidden in many parts of the North—together with white clover for fertility and creeping red fescues for the shadier parts of the lawn, will in the long run require the least amount of maintenance. It’s better to plant bluegrass mixtures than planting just one variety. With two or more, if one is not acclimated to your soil or not resistant to disease in your particular microclimate, the others probably will be. That is why native Kentucky bluegrass is usually added to fine bluegrass mixtures for a typical lawn. It doesn’t need to be coddled. For low maintenance, the volunteer bluegrass of your region may be even more acclimated than what you buy as Kentucky bluegrass. Bluegrass and acid soil do not mix. The soil pH should be above 6 at least, and closer to 7 for the finer varieties. Bluegrass is sown at about 2 to 3 pounds per 100 square feet—more for Kentucky bluegrass, less for Merion and the finer-seeded varieties. Directions always come with the package. White clover has a very fine seed and 4 to 5 ounces per 1,000 square feet will suffice. Since such a small amount is hard to spread evenly, it’s best to mix it with the grass seed. In the North, plant grass in the early fall after rains have moistened the soil well. Southern lawns are best planted in early spring. Ideally, the clover should be planted in very early spring, broadcast over the new lawn, even though white clover will survive fall sowing. It will generally come up as a volunteer whether you sow it or not after the lawn is mowed a couple of years. BENT GRASSES The bents are at the very low end of the low-maintenance measuring stick. They make probably the finest lawns of all, very nice for golf greens and croquet courts. But they require much care, pampering, mowing, etc., and do not like dry weather. There are two types, usually referred to as Colonial, and Creeping or Velvet. Both are used in mixtures where a very fine lawn is desired, but neither is recommended for low maintenance. Mowing Among the Superneats, mowing has been raised to a high art. As a general rule, grass should be kept 1 1/2 inches high, they say, bent grasses and Bermuda grass shorter than that, coarse fescues a little taller. But if low maintenance is your goal, 2 to 3 inches will suffice for bluegrasses, zoysias, and fescues, bent grass should be avoided, and so only Bermuda grass needs to be mowed short. Most people scalp their lawns too close, leaving the grass weak and prone to disease, drought injury, and overly reliant on added fertilizer. Blades of grass are the grass’s leaves, and the amount of leaf exposed to sunlight determines how much chlorophyll and other life supporting substances the plants produce. According to the experts, if you raise the height of the cut just /e inch, you increase the leaf surface 300 square feet per 1,000 square feet of lawn. Lowering it 1 inch has the opposite effect. Clipping most grasses below 1½ inches has an effect not unlike trying to grow grass in the shade. Obviously if you clip routinely at 2½ inches, the grass will be that much more vigorous to withstand drought, shade, weed encroachment, and the need for additional fertilizer. If maintaining grass height at 21/2 to 3 inches offends your sense of a carpet lawn (how about thinking in terms of a shag rug?), then at least you should vary cutting height by season. In early spring, when conditions for growth are most favorable, cut at the minimum height for the variety of grass you have. In hot, dry midsummer, cut higher. In the early fall when moister weather returns, switch back to the minimum, and then clip high in the late fall. A more important number to watch in low-maintenance management is not cutting height, but frequency of mowings. No matter what height you choose, the old rule of thumb is not to let grass grow more than 100 percent of that height before mowing again. If you maintain at 3 inches, you can let it grow another 3 inches before mowing and not weaken the plants. If you maintain at 1 inches, you will obviously mow twice as often. There won’t be much difference on the wear and tear of the mower between mowing off 3 inches and mowing off 1½, but you operate your mower twice as much and spend twice as much time at it. The mower will wear out in half the time. The difference in the appearance of the two lawns will not be great except in the eyes of the Superneats. Another advantage of mowing only half as much as the Superneats is that the mower blade will stay sharp twice as long. Dull blades injure the grass and shorten the life of the mower. Even Superneats resist getting down under the mower, removing the blade, and sharpening it. Turf scientists test new grasses with dull mowers because, unfortunately, most mower blades are dull most of the time. Low-Maintenance Lawn Mowers It is almost ridiculous to try to compare lawn mowers anymore. The leading mowers often have components made by the same factory or another just like it. I bought a riding mower this spring, my first (and for my wife who does not approve of walking tractors the way I do). The Bolens I almost bought has a body from Denmark and a motor from Briggs-Stratton. In fact, about the only part of it that was Bolens originally was the name, which in reality stood for the place where all the parts were put together. The same is true of most every manufacturer. All those little tractors with such American names on them like Ford and John Deere are made in foreign countries. And motors? Well, someone makes the spark plugs, and someone else makes the blocks, and someone else the clutch belts or gears, and likely as not, the same manufacturer supplies competing brands. Within any line of lawn mowers, however, some are made better than others, and the price reflects that difference. The difference between a riding lawn mower and a lawn tractor is about six more years of trouble free operation. The tractor is built a little heavier and has a motor built to run a little longer. In buying, the most important aspect to pay attention to is the motor. If they are all Briggs-Stratton, or Kohler, with here and there a Tecumseh, how do you judge them? Some of these motors are cast iron or have a cast-iron piston sleeve, and the ones that do not will not last as long, and you will not pay quite as much for them. It pays to buy motor quality If you have to economize, cut down on accessories or convenient designs. Thus, on the Bolens I liked (it had the mower up front and a steering system designed for easy trimming around trees), the motor was an 8-horsepower (HP) Briggs. The price, as I recall, was something like $2,300. The same dealer handled Snapper. A Snapper of slightly smaller mowing width, with the mower deck between the front and back wheels, had an 11-HP Briggs motor. Its price was $1,500. There was another mower there that appeared to be quite similar to the Snapper with an 11-HP Briggs on it, too, but it was cheaper yet. The difference? The 11-HP motor on the Snapper was an I/C 11 HP, which is to say a heavy-duty industrial/commercial model, and what that means principally is that it had cast iron in the engine block where cast iron is still necessary for long life, especially in the piston sleeve. It was worth every cent more than the other 11-HP Briggs that was not I/C. And it was a much better motor than the 8-HP regular Briggs on the Bolens mower. What I would have paid about $800 more for in the Bolens was easier operation and a more comfortable seat and only a few inches more capacity. For me, the Snapper was a better buy. Actually, for low-maintenance purposes, a walk-behind tractor like the old Gravely I have operated for 18 years now, is even more practical. You pay less if you are willing to walk rather than ride (and thereby also keep your weight down, hopefully). You also get more use out of them because such tractors double as trimmers and because with other attachments you can cultivate the garden with them. There is an even more economical way to handle mowing chores, but one not popular in America. The walking tractors, especially those made in Europe and Japan—Mainline, Ferrari, Pasquali, and others used mostly as rotary tillers—all can be equipped with what is called a mulching sickle-bar mower. (There are American models made specifically to run a sickle-bar mower and take cultivating shovels.) Write to Kinco ( 1669 Grand Avenue, Saint Paul, MN 55105) for a description of their models. In any case, the advantages are several. For the same mowing width, you need less horsepower to run a sickle bar than a rotary mower. The mulching cutter bar will cut grass almost as low as a rotary and drop it immediately behind the bar, rather than send it in great slugs and globs out the side or rear where it piles up and is slow to decay into the grass. Unlike regular sickle-bar mowers for hay, the little mulching bars cut better; they do not plug up on wavy grass like the hay cutters tend to do. Although the sickle-bar blade is more difficult to sharpen, it does not dull as fast as a rotary blade. Last but not least, the sickle bar is a hundred times safer. You can cut a finger or toe off in them if you are so foolish as to put a finger or toe between the guards, but the sickle bar does not throw rocks and sticks into your flesh or your windows, nor can you gash the blade on sidewalks or tree roots. Trimming is easy and much safer. There are sickle-bar attachments for riding garden tractors, too, but they are not as handy nor do they cut as well as the little (3 to 4 feet) mulching bars. The one I have tried is made in Italy and sold by Mainline, whose advertisements appear regularly in garden magazines. When I last checked, the cost for the mower ran from about $800 to $1,200 and the attachment was about $400. If you have tall weeds to mow, this mower will perform that task much more easily than any rotary mower. The mulching sickle bar does not mow as neatly as a rotary mower does, so I don’t expect it to ever become popular in the world of Superneat, but you should at least be aware of it. -- Increasing Mower Life Keeping your mower in good running order is not a low-maintenance proposition, but regular maintenance can prevent costly high maintenance. At the International Lawn, Garden, and Power Equipment Expo in 1985, a survey of mower repairmen revealed that the number one cause of mower malfunctioning was not adding motor oil when necessary. So check your oil regularly, as specified in your owner’s manual. The second leading cause of motor damage came from not cleaning the air filter regularly (see your owner’s manual for instructions). Striking rocks and other objects with the blade was the third most common cause. Fourth was not changing the oil as often as required, which really should be part of number one, making poor motor lubrication the all-time-high gremlin of mower failure. The last significant cause of short mower life was overheating, caused by clogged cooling fins. Clean the dirt out of the fins on the motor block every spring when you haul the mower out of storage. Those fins are designed into the block very purposely, but they can’t keep the motor cool if they are full of debris. The easiest way to clean them is to run a wire through every groove between the fins to push out the dirt. Use an air compressor to blow the remaining dirt away, if you have one. Lung power is sufficient as an alternative. Some folks blast away with a stream of water when the engine is cool, but water could do more harm than good. |

Prev: Decks, Porches, and Patios |