TOOLS AND EQUIPMENT

As with any other craft, if you intend to take your sewing seriously, and to produce neat, professional-looking work, it’s essential you have all the necessary tools of the trade. Never try to make do with inadequate or poor-quality equipment, accessories or gadgets-it just is not worth it. Scissors which are not as sharp as they should be, needles which are the wrong size for the job, thread which is unsuitable for a particular fabric . . . small details perhaps, but they are enough to spoil your finished garment, and an insult to the time and effort you might have spent in the sewing.

Ideally a room should be set aside for your sewing activities-- if this is not possible, then a corner of a room will do, somewhere where you can have your machine permanently in position, in a good light and with a chair at a comfortable height for working. Your equipment, tools and gadgets should be kept conveniently to hand, and in neat order. Bookshelves on the wall nearby can take your sewing books, leaflets and patterns. A felt notice board or section of cork on the wall is also useful for pinning up design ideas, pattern envelopes, cuttings from papers or magazines.

The following list represents the ideal collection of equipment the home dressmaker should possess. Some items however do fall into the luxury class, and it’s perfectly possible to produce attractive work without owning these items-it should be fairly obvious which these luxury items are. Also, the tools you collect naturally should bear some relation to the type of sewing you intend to do-if you are unlikely, for instance, ever to make up garments in velvet or any other pile fabric, then a velvet board will be unnecessary.

Needles. Have a good supply of different sizes of both machine and hand-sewing needles. For hand-sewing, No. 7 darners are best for basting, and No. 9 sharps or straws for fine work. ‘Sharps’ are all-purpose, round-eyed needles of medium length; ‘betweens’ are short, round-eyed needles used for very fine sewing; ‘milliners’ are round-eyed, long and slender; they are used for basting. hand-shirring and similar sewing tasks; ‘crewels’ are medium length with long eyes that make threading easy, and they can carry several strands of thread at the same time. For machine-sewing, use No. 11 for fine fabrics, No. 14 for general use, and No. 1 6 for heavy fabrics.

Pins. Medium-sized steel ones are best as these won’t leave rust marks or holes in your fabric. Pins with brightly-colored glass heads are also useful, as they are easy to see and handle. Scissors. Always buy the best-quality scissors and shears, and use them only for fabric, never on paper. As soon as the blades show signs of dullness, have them sharpened. The following list is the ideal selection of types and sizes of scissors and shears for all sewing purposes:

1. Bent-handled shears. These are best for cutting fabric as the blades rest flat on the cutting surface, and you don’t have to lift the fabric when cutting round a pattern. Left-handed models are usually available.

2. Trimming scissors. Good for trimming and clipping seams and for general use.

3. Small embroidery scissors. These are useful for cutting buttonholes, threads and other small jobs.

4. Pinking shears. Use these to cut a zigzag edge and for finishing hem edges and seams. Never use pinking shears to cut out a garment.

4. Scalloping shears. These are similar to pinking shears but cut a scalloped edge instead of a zigzag edge. Use them for finishing hem and seam edges too.

--Tape measure. A flexible type, made of a material that won’t stretch or tear is the wisest choice. The measure should be reversible (markings appear on both sides), have centimeter and inch markings, and have metal tips at each end.

--Yardstick. Select a smoothly finished one which won’t catch on the fabric. This is used to measure fabric, to check grain lines, and to make your own patterns.

--Hem gauge. A measuring device marked with various depths so that hems can be turned and pressed in one step.

--Sewing gauge. This is a 6-inch gauge with a moveable indicator. It’s convenient for measuring short distances.

--Skirt marker. There are two basic types of hem marker avail able: the type of marker which uses pins is the most accurate, but it does require the help of a second person. The bulb type of marker which uses powdered chalk to mark the hemline on your skirt or dress permits you to do the job on your own.

--Stitch unpicker. A useful gadget which will unpick an entire seam in a matter of seconds.

--Set square. Essential for drawing right angles and useful for all short straight lines.

--Thimble. Even if you think you can manage without one, do persevere—eventually you will find you can work more easily and quickly with it.

--Paper. Large sheets of strong white or brown paper for making paper patterns. Small sheets for sketching designs.

--A soft pencil. For drawing out paper patterns, sketching your designs, and occasionally for marking wrong side of fabric with guide lines.

--Dressmaker’s tracing or carbon paper. For transferring pattern markings to fabrics and interfacings. A packet of assorted colors is most convenient, as you can then choose a suitable color for your fabric—pale-colored carbon papers are best for light-colored fabrics, as the darker ones leave too heavy a mark which can sometimes show through on to the right side of the finished garment.

--Tracing wheel. Used in conjunction with carbon or tracing paper. The tracing wheel has tiny teeth which are rolled over the carbon paper where the pattern marks are required to be transferred to your fabric. To get a better impression from the carbon and to protect your working surface, slip a piece of heavy cardboard under the fabric before starting to use wheel.

--Tailor’s chalk. This is used on fabrics which cannot be marked with carbon to transfer pattern markings. Because the chalk rubs off easily, it’s used for temporary markings only. Available in different colors, but white and blue are used most often as they are less likely to stain the fabric.

--Chalk pencils. Available in colors, and used also to transfer pattern markings to fabric. Because these pencils can be sharpened to a point, they give a thin, accurate line.

--Beeswax. Useful for strengthening thread, particularly for sewing on buttons as it also acts as a lubricant, Beeswax can usually be bought in a holder having grooves through which the thread is pulled for waxing.

--Basting cotton. Use white for dark-colored fabrics; pale contrasting colors for light-colored fabrics. Avoid bright cottons on pale fabrics as traces of color can sometimes be left behind.

--Sewing threads. Again a good varied selection of types, sizes and colors is best. Mercerized cotton is best for most everyday purposes; for heavy fabrics, such as tweed, suiting and corduroy use size 40 mercerized cotton; for lighter weight fabrics, use size 50.

Unmercerized cotton thread is also available in sizes 10—60. No. 40 has the largest shade range.

Button and carpet thread is extra heavy for hand sewing only. Silk thread is strong and has a certain amount of elasticity. It can be used on silk, silk-like and fine wool fabrics. Buttonhole twist is a strong, silk thread with a special twist for making hand-worked buttonholes, sewing on buttons and decorative hand or machine stitching. Synthetic thread is a polyester thread recommended for use on knits, stretch, man-made and most drip-dry fabrics. Its elasticity makes it compatible with knits and other stretch fabrics. There are also excellent multi-purpose threads available which can be used for all sewing purposes, in a wide range of shades.

--Iron and ironing board. Careful pressing as you go along is essential for a perfectly finished garment. Keep iron and ironing board conveniently to hand as you work. A combination steam-dry iron is best, with a reliable temperature control for different fabric types. The ironing board should be well-padded. Sleeve board. A small ironing board for pressing sleeves and difficult-to-reach areas.

--Tailor’s ham. A firm, rounded cushion for pressing areas that need shaping such as curved darts or seams at shoulder, bust or hip line.

--Velvet board. A length of canvas, covered with fine upright wires, which is used for pressing nap and pile fabrics. The pile side of the fabric is pressed over the wire side of the board to prevent it from matting or flattening.

--Pressing cloths. These are used to prevent fabrics from getting a shine as sometimes occurs when fabrics come into direct contact with a hot iron. Cheesecloth or muslin pressing cloths are good for cottons and linens; woolen pressing cloths are best for wool fabrics. Use pressing cloths dry over delicate fabrics, damp over linen or cotton.

--Pressing mitt. Useful for pressing curves. To make your own pressing mitt, cut a rectangle of paper 7in. by 9 Curve the corners at one end, and use this pattern to cut out three layers of calico. Stitch a 0.5-in. hem along the straight edge of one layer. Sandwich this layer between other two, and stitch round curved and side edges. Turn right side out, so hemmed edge of first layer is inside mitt. Pad the two unhemmed layers with wool, turn in --in. hem on both straight edges and hemstitch neatly together.

--Steam dolly. Excellent for quick, efficient pressing of seams. Cut a strip of light-colored woolen material, 1 2in. by 2in., and roll up tightly, graduating to a point at one end. Tie a length of tape round centre. To use, the point is dipped in water and drawn along the fold of a seam which is then pressed open with the iron.

--Cutting board. If you don’t have a large old smooth-surfaced kitchen table or similar flat surface to work on when cutting out patterns, make yourself a cutting board from a piece of hard- board, about 4ft. by 3ft. This can be placed on top of a table, on the floor or even on a bed, and used as a working surface for cutting out and assembling pattern pieces.

--Pattern bag. Cut an oblong of strong brown paper, 12in. by 20in. Lay it on a flat surface with shorter edges at top and bottom. Now make a 6-in, fold from lower end, and machine- stitch down sides, to form a ‘pocket’. Fold top end down to form a flap, making this fold 8in. from first fold. Keep your patterns in orderly fashion in this bag.

GUIDE TO FABRIC TYPES

Those of you who already make your own clothes will know how exciting fabric shops and departments can be. For new comers to dressmaking, this is a pleasure still to come! In fact the selection of a suitable fabric can sometimes be difficult because there is such a wonderful range of designs and fabric types from which to choose. Don’t however be too bewitched by the attractive eye-catching display—it is important to choose the right weight and design of fabric for the garment you intend to make. It’s well worth while spending time in fabric stores and departments just getting to know the many types of fabric available before you actually buy any. Study the labels and discover which fabrics are washable, which are crease-resistant, which need special handling and sewing techniques. The following guide describes a few of the basic fabric types. In general terms, fabrics may be divided into two main groups: woven and knitted. The majority of fabrics are woven.

Cotton. These are plain-weave natural fabrics, firmly woven and available in a wide range of weights and patterns. A light starch when washing cotton garments will help to retain the natural ‘crispness’ of the fabric.

Batiste. A fine lightweight plain-weave fabric, usually of cotton.

Burlap. A coarse fabric, which is a plain weave of jute, hemp or cotton used for sportswear.

Canvas. Heavy, strong, plain-weave fabric useful for sports wear. A heavier form of canvas is known as duck.

Challis. A soft lightweight worsted cloth available in solid colors or prints. Good for dresses, and for children’s wear.

Two simply-styled beach dresses—easy enough for a beginner to make.

Chambray. A cotton fabric with warp threads in a color, and white used as a filling. The result is an attractive two-tone effect. Chiffon. A transparent very sheer fabric of highly-twisted silk or synthetic yarns.

Chintz. A glazed plain-weave cotton in solid colors or prints. Corded fabrics. These are available in different weights, with the cording—or ribbing—in a variety of thicknesses. Corded fabrics include: Bedford cord, broadcloth, poplin and faille.

Crêpe. This refers to the surface texture of a fabric, and can be produced in silk, synthetic, cotton or wool fabrics, from sheer to heavy weights.

Denim. A cotton fabric usually made with colored warp yarns and lighter or white filling yarns.

Dimity. A sheer crisp cotton which may be plain, checked, striped or printed.

Flannel. Woven of wool, synthetics or blends and generally it has a very lightly napped surface.

Gabardine. A fine, close twill of worsted, cotton or synthetics. Georgette. Special weave; crinkled fabric, fairly lightweight. Jacquard weaves. The jacquard loom produces various patterned-weave fabrics. These fabrics include: table linen, brocade (in which gold or silver threads may be used) and damask.

Knitted fabrics. Knit fabrics are made of yarn which is looped together like chain stitches instead of being woven. There are two basic types of fabric: the horizontally knitted fabric which stretches mostly in a crosswise direction, and the vertically knitted fabric which is more tightly woven and with less give than the horizontal knit. Tricot is an example of the vertical knit, with fine vertical ribs on its right side, horizontal on the reverse. Double knits have two layers of fabric, with right and wrong sides almost identical.

Lace. Many varieties available in cotton and silk, ranging from delicate Chantilly lace to sturdy Venise. In some types, the mesh design is outlined in fine embroidery.

Laminated fabrics. Also known as bonded fabrics. These fabrics consist of an outer or face fabric of almost any fiber fused to a lining fabric such as tricot or taffeta. The permanent backing gives stability to the face fabric and prevents stretching. Lawn. A closely-woven cotton somewhat resembling voile but with more body. May also be made in synthetic fibers.

Linen. Natural fabric which ranges in weight from sheer ‘handkerchief’ linen to heavy suitings. Occasional thicker places in the yarn give a slightly slubbed effect.

Man-made fabrics or synthetics. This term includes all fabrics made from chemically-produced fibers—rayon, nylon, acetate. Dacron, Orlon, Terylene, Crimplene are just a few of the synthetic fabrics available. All are strong and hardwearing.

Napped fabrics. ‘Napping’ is a process which lifts the short fibers, so they form a hairy or down surface. This nap may be brushed down or left unbrushed. Doeskin, fleece and suede cloth are all napped fabrics.

Organdie. A very lightweight plain-weave cotton with a crisp finish.

Organza. Similar to organdie but of silk or rayon. Used for evening dresses and blouses.

Peau de soie. A satin weave with a luster duller than satin itself. Comparatively heavy.

Pile fabrics. Pile fabrics are composed of raised loops which are cut so they stand up from the surface. Pile fabrics include velvet, corduroy, fur fabrics, velour and velveteen. It’s important when cutting all pile, and also napped. fabrics that the garment pieces are cut with the pile or nap running in the same direction, otherwise the sections of the completed garment will appear to have been cut from different shades of the same color. Velvet, velveteen and corduroy should all have the pile running towards the top of the garment for the richest and darkest color.

Pique. A true pique is woven with lengthwise or crosswise ribs; but there are several fabrics commonly referred to as pique which actually are not, as the raised effect is created not by $ weaving but by pressing and it may not be permanent.

Plissé. A cotton fabric crinkled by shrinking sections with a chemical. Used for lingerie and sleepwear.

Quilted fabrics. These fabrics usually consist of three layers of fabrics—the top fashion fabric, a layer of wadding filling and a backing. Naturally the resulting complete fabric is bulky and warm, and so is ideal for jackets and coats. Available in different weights in cottons, silks and synthetics.

Sailcloth. A member of the canvas family but in lighter weights. Available in solid colors and prints.

Satin. A shiny silk or synthetic fabric using the basic satin weave: that is, either the warp or filling has threads with long ‘floats’ (a thread which skips over or under several threads) running in the opposite direction. -

Seersucker. A plain-weave fabric with permanent woven crinkle, available in striped, checks, and plaids. The crinkle can be an all-over texture on the fabric, or it can be arranged in ‘stripes’, narrow or broad, to form a pattern in itself.

Serge. A flat ribbed fabric, with the rib going diagonally from the lower left to upper right, Of wool, worsted, cotton or synthetics.

Sharkskin. Two types of fabric are known as sharkskin: one is a worsted suiting, generally in grey or brown, with a small weave design resembling the skin of a shark; the other is a somewhat heavy, semi-crisp summer sportswear material made of acetate, rayon or blends.

Silk. A luxury natural fabric. Various weights and types avail able: e.g. honan, a fine-quality wild silk; pongee, a lightweight fabric with nubs and irregular cross ribs; shantung, similar to pongee but heavier and rough; tussah, a coarse uneven light brown silk.

Stretch fabrics. Many popular fabric types and weaves have the additional feature of stretch. Included among these are denim, twill, gabardine and poplin. Those that stretch length wise are generally used for trousers; crosswise stretch goes into dresses, skirts, blouses, jackets and shirts.

Surah. A soft, lustrous fine twill of silk or synthetics in solid colors or prints.

Taffeta. A fine, crisp plain-weave fabric smooth on both sides and with surface sheen. Often used as lining fabric.

Ticking. Originally used for mattresses, ticking stripes now make smart sports suits and coats.

Tulle. A silk or synthetic net with a six-sided mesh. Used in layers for evening dresses.

Tweed. A rough plain or twill-weave fabric. Generally has contrasting slubs and nubs. Good for winter coats, suits and skirts. Twill. There are various types of twill-weave fabrics. The basic twill weave runs up from left to right in a diagonal line. Variations include the popular herringbone (also called ‘chevron’) so named because it resembles a herring’s backbone.

Voile. A light, semi-transparent fabric usually of cotton. In prints and plain colors.

Whipcord. A rugged, hardwearing fabric distinguished by a prominent upright slanted rib. A twill weave.

Wool. A natural fabric produced from the hair of sheep or lamb. Many kinds and weights available: e.g. Viyella, a lightweight fabric; Afghalaine, dress-weight, soft and fine; velour, a heavier coat-weight cloth.

Worsted. A fabric produced from yarn spun from combed wool. Generally considered as belonging to the wool family, though the original fibers are obtained from animals other than sheep. For instance, Angora and Mohair are produced from the Angora goat or rabbit; camel hair comes from the hair of the Asiatic camel; cashmere is from the hair of the Kashmir goat.

THE RIGHT NEEDLE AND THREAD

Whether you are sewing by hand or by machine it’s essential you use the correct weight and type of thread for your fabric, and also the right needle size. There are good multi-purpose threads available which can be successfully used with all fabric types, but as a general rule natural threads should always be used with natural fabrics, and synthetic threads with synthetic fabrics. Using a cotton thread, for instance, with a nylon fabric can cause ugly puckering of seams, and when washing the garment the cotton thread might shrink slightly, whereas the fabric will not.

On the other hand if you use a synthetic thread to sew a cotton dress, when you come to iron the garment you will in all probability set your iron at a hot temperature to suit cotton— but this temperature could quite easily melt the synthetic thread which should only have a cool iron. The following chart gives a general guide to the correct thread and needle size for different fabrics.

---Table

Fabric:

Fine—net, organdie, lace, lawn, voile, chiffon, tulle Lightweight—silk, gingham, muslin, poplin, seersucker, crêpe, taffeta

Medium-weight—tweed, wool, jersey, corduroy, linen, satin, brocade, velvet. Suitings

Heavyweight-twill, canvas, duck, furnishing fabrics, foam-backed

Stretch fabrics

Special fabrics-PVC, leather, suede

Thread:

Natural: cotton 50

Man-made: Terylene

Natural: cotton 50

Man-made: Terylene

Natural: cotton 40

Man-made: Terylene

Natural:

cotton 36-40

Man-made: Terry

Terylene

Terylene

Needles—Hand:

9

8—9

7—8

6

Lightweight:

9

Heavyweight:

9

9

Needles—Machine:

9—11

11—14

11—14

Machine stitches per inch:

12—1 6 (natural);

12—14 (Terylene)

12—14

12—14

8-10

10-14

(use special stretch stitch)

6-10

WHAT SIZE AND SHAPE ARE YOU?

The key to successful dressmaking is to establish the right paper pattern size for your shape and size of figure. Of course patterns can be adjusted to allow for any personal idiosyncrasies in your shape, for few of us are exactly ‘stock size’, but if you start with a paper pattern which is as near as possible to your measurements, there will be fewer adjustments to be made, and the finished result should be more professional looking.

Commercial paper patterns are grouped under eight different types, and most figures fall into one or the other of these eight categories. Read the description of each category, below, and decide which one seems to be most like your own.

(Note. The names of these figure types are not descriptive of age. The types are based on height, body proportions and the contours of the figure. Thus some teenagers, for instance, will find that a Half-Size pattern fits them best; and there are adults whose measurements and figure proportions are best fitted by a Young Junior/Teen type pattern.)

Girls’. From 4ft. 2in. to 5ft. 1 in. This is the smallest of the range of figure types. Because the bustline is not defined on this just- developing figure, no .underarm dart is needed in the dress bodice.

Chubbie. From 4ft. 2in. to 5ft. 1 in. This is for the growing girl who weighs more than the average for her age and height. Girls’ and Chubbie patterns are the same height in comparable sizes.

Young Junior/Teen. About 5ft. 1 in. to 5ft. 3m. This range is for the developing teen and pre-teen figure which has a very small, high bust with a waist larger in proportion to the bust.

Junior Petite. About 5ft. to 5ft. 1 in. This is a short, well- developed figure with small body structure and a shorter waist length than any other type.

Miss Petite. About 5ft. 2in. to 5ft. 8 in . This is a shorter figure than a Miss and has a shorter waist length than the comparable Miss size but is longer than the corresponding Junior Petite.

Miss. About 5ft. 5in. to 5ft. 8in. This is well-proportioned and well-developed in all body areas, and is the tallest of all figure types. This type can be called the ‘average’ figure.

Half-Size. About 5ft. 2in. to 5ft. 8 in. This is a fully developed shorter figure with narrower shoulders than the Miss. The waist is larger in proportion to the bust than in the other mature figure types.

Woman. About 5ft. 5in. to 5ft. 6in. This is a larger, more mature figure of about the same height as a Miss. The back waist length is longer because the back is fuller, and all measurements are larger proportionately.

Taking your own measurements:

To establish your exact figure type and size it’s necessary to take your actual body measurements—these are the measurements of your own body at the specific points listed below. These are not the measurements of your pattern; a pattern always adds to the body measurements sufficient ease for movement.

When taking your measurements never be tempted to cheat by adding or subtracting inches where you would like them to be. Or to say to yourself, ‘I am going to start dieting next week, so I’ll allow for the inches I shall lose!’

Be honest with yourself about your figure as it’s now. A garment which is made exactly to measure, whatever your shape or size, will look several times better than one that is made to the figure you would like to be.

If possible persuade a friend or member of your family to help you take your measurements. Ask her to write down the measurements as soon as she has taken them—then believe them! Be sure too that you take the measurements over the sort of bra and girdle you normally wear and are likely to be wearing for some time. Different foundation garments can add and subtract inches. Measure at the following points:

1. Bust. This should be taken round the fullest part of the bust, with the tape measure held well up at the back. Don’t pull the tape too tightly or for that matter leave it too slack. It should just comfortably meet round your bust.

2. Waist. Place the tape round your natural waistline. Again don’t pull it too tightly, and stand relaxed, without trying to pull in your tummy more than you would normally do.

3. Hips. Measure round the fullest part of your hips—this point is usually about 7—8in. down from your waist but it varies from one figure to the next.

4. Centre back to waist. Find the knobbly bone at the top of your spine and measure straight down from this point to your waistline. It’s practically impossible to take this measurement without the help of a friend.

Finally write down your height without shoes.

Your figure type is based on two of these measurements: your height and your back waist length. If you are short-waisted with a well-developed figure, you will probably need a Junior Petite or Half-Size pattern. If you have a very young figure with a high, small or undefined bust you may be a Girls’ or a Young Junior/Teen figure type. If you are tall, and have an average or long-waisted figure you may need either a Misses’ or Women’s pattern.

If you find two figure types that have the same bust, waist and hip measurements as yours, check the back waist lengths, and choose the type with the back waist length nearest to your own measurements. If your measurements fall between two sizes, select the smaller size if you are small-boned, or pick the larger size if you are large-boned or full-bodied.

If you are going to make a dress, blouse, suit or coat, select the size with the bust size nearest to yours.

If you are going to make a skirt, shorts or trousers, then select the size by the waist measurement. If your hips are much larger in proportion to your waist, then select the size by the hip measurement and alter at the waist.

If the pattern includes more than one type of garment, such as a mix and match set of blouse, jacket, skirt and trousers, then select the pattern by the bust measurement. If necessary adjust the hip measurement to fit.

Taking measurements for trousers:

Stand evenly on both feet. Measure snugly over the under garments you usually wear with trousers. Measure at the following points:

1. Waist.

2. Hip.

3. Thigh.

4. Knee.

5. Calf.

6. Round instep and heel.

7. Side length, from waist to desired finished length.

8. Crutch length—taken sitting down, from natural waistline to the top of the chair seat, then add on ¾ in.

Taking children’s measurements:

Always buy children’s patterns by size, and not by age. When measuring babies, take the weight and the height. If weight and height fall into different sizes, decide proper size by weight.

Children should first be measured round chest, taking the tape under the arms and over fullest part of chest at front and the bottom of shoulder blades at the back. Measure the child’s height by standing him or her against a wall, without shoes.

Taking boys’ and men’s measurements:

For coats and jackets, measure around the fullest part of the chest. For shirts, measure around the neck and add .in. for the neckband. For shirt sleeves, measure from back base of neck along shoulder to wrist. For trousers, measure around waist over shirt (not over trousers). Be sure to measure at natural waist as this determines size even if trousers are designed as hip-huggers. Measure hip round fullest part of hip.

MEASUREMENT CHARTS

As approved by the Measurement Standard Committee of the Pattern Fashion Industry.

BABIES

Age | Newborn (1-3 months) | 6 months

Weight -- 7—13 13—18

Height --1 7—24in. 24—26

TODDLERS’

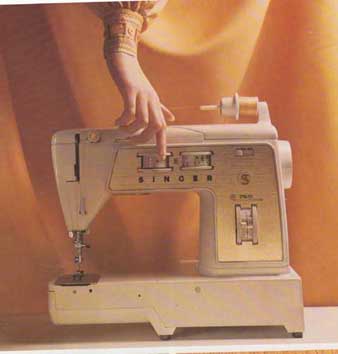

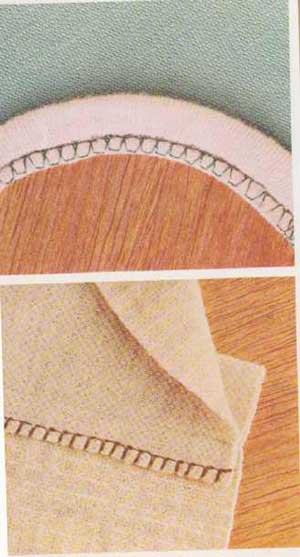

Top: the Singer luxury 760 sewing machine and. below, an example of the edge stitching the machine will produce.

--- Table

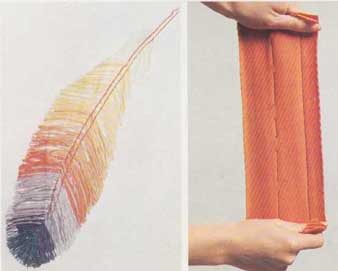

More examples of stitching from the Singer 760 sewing machine. Top: a straight stitch that stretches with the fabric, and speed-basting embroidery.

Bottom: decorative stitches, and blind hemming.