A flock of calm chickens is a joy to be around. Chickens that squawk and fly every time you come near aren’t much fun. Part of flighty behavior is genetic in that some breeds are more easily frightened than others, but all chickens may be taught to be calm. The secret is for you to be calm when you are around them.

Whenever you approach your chickens, whistle or sing so they’ll hear you coming and won’t be startled. Spend at least 5 minutes a day with your flock. The more time you spend, the less easily frightened and the friendlier your chickens will become. Walk slowly among them, talking or singing softly. Some folks pick up and pet their chickens. Your neighbors may think you odd, but your chickens will love it.

Peck Order

Chickens are social animals. They are happiest when they are with others of their own kind. In every group of chickens, one emerges as the leader. Scientists call this “establishing the peck order.” The peck order reduces stress by ensuring that every chicken knows how to relate to every other chicken. Most of the time, roosters are higher in rank than hens. If a hen is higher in rank than a cock (in other words, the cock is “henpecked”), it is usually because the cock is young and inexperienced or old and weak.

Chicks start establishing their place in the peck order when they are only 3 weeks old. After a couple of weeks, most of the fighting stops, because the peck order has been established. If a new chicken is introduced, the fighting starts again until the new chicken has found its place in the peck order.

When two chickens meet for the first time, their first order of business is to establish the peck order. The farther a chicken is from home, however, the more timid it becomes. The home flock therefore has an advantage over any newcomer, which will get badly beaten up if you simply turn it loose.

Instead, keep the new chicken apart from the flock for a few days. After the new chicken becomes used to you, start bringing in your other chickens, one at a time. Introduce the lowest-ranking ones first. They are usually the youngest or the oldest birds. After the new chicken has met all the other thickens one by one, put her with the whole flock. She should get along fine, because she has already established her place in the peck order. She will probably rank somewhere in the middle.

If you are introducing several new birds, you can help ease the transition by placing a fence between the old flock and the new for a few days. When you remove the separating fence, leave each group its own feed and watering station. If both groups include a mature cock, you can expect the cocks to fight, even through the fence.

Sparring is normal when chicks are young; once the peck

order has been established, fighting should subside.

When a rooster gets his hackles up, watch out — he’s

threatening to attack

Aggression

Most roosters are not mean, but they will defend their flock from a threat. However, they can’t always tell when a threat is real. Something as simple as floppy shoelaces may look like a real threat to a rooster. If you always wear jeans when you tend your flock and one day you wear overalls or a rain suit, the floppy legs might be perceived as a threat. Sometimes a rooster will feel threatened by any man, or any woman, or any child, or any person but the one who normally brings feed and water.

A rooster may learn to be mean if he gets teased by a person or another animal. Children sometimes poke sticks at chickens and dogs enjoy chasing them, in both cases scaring the chickens out of their meager wits. Keep dogs and misbehaved children away from your flock, or teach them how to behave properly.

Sometimes a rooster gets the notion that you are a big chicken he must outrank in the peck order. He may move toward you sideways, with his head down, pretending he is looking at something on the ground. The term cockeyed comes from this ability of a rooster, or cock, to look someplace else while he is really watching you. He may not actually attack, but he may threaten by rushing at you or bumping against your leg. Try to make friends with him by picking him up and rubbing his wattles.

If a rooster does attack, pay attention to what you are wearing or carrying, especially anything different from the usual. Maybe he doesn’t like your rubber boots, flip-flop sandals, or hare legs or the way the new feed bucket swings in your hand. If you are doing or wearing something different, avoid it next time and see if it makes a difference.

‘When a rooster gets his hackles up — that is, raises the feathers on his neck to make himself look big and fierce — he means serious business. Occasionally a cock remains mean no matter what you do. Such a rooster is big trouble. Get rid of him.

Chicken Talk

Chickens use at least 30 different sounds to communicate. If you pay attention to the sounds they make as they engage in different activities, you’ll soon be able to close your eyes and know what they are doing by the sound. Recognizing these sounds lets you understand your flock’s mood and helps you be a better manager.

Cackle is the sound a hen makes after laying an egg. Humans tend to think she’s bragging, but she’s really protecting her future offspring by drawing the attention of potential predators to herself as she moves away from the nest.

Growl is the best way to describe the sound a hen makes when she’s on the nest and you reach underneath her to collect eggs. She’s telling you to leave the eggs alone so she can hatch them.

Peep is a chick’s way of communicating with its mother, even before it breaks out of the shell. Chicks peep to keep in touch with one another and with their mother. They have many ways of peeping, depending on whether they are content, uncomfortable, afraid, lost, or sleepy.

Cluck is a sound made by a mother hen so her chicks will know where she is. This loud, clipped sound is so distinct that a hen with chicks is often called a clucker or a cluck.

Brrr is a warning sound a mother hen makes when she senses danger. It tells her chicks to hide by flattening against the ground until they hear her cluck.

Hawk is the sound the highest-ranking chicken in the peck order makes when a bird flies overhead. It causes the other chickens to run for cover, even if the “bird” turns out to be a high-flying airplane or a low-flying butterfly.

Screech is what a chicken does when it is unexpectedly grabbed to call a rooster or a senior hen to the rescue. When you hear this sound, you know someone or something (perhaps a dog) has gotten hold of one of your chickens.

Crow is what a rooster calls for lots of reasons: to establish territory, to brag after winning a fight, and to keep the flock together. When a rooster is about to crow, he flaps his wings and stretches his neck. Nearby roosters who hear the crowing may answer. Crowing must be important to chickens; if no rooster is around, some times an old hen will crow.

Singing is the best way to describe the melodious sound made by happy hens. Hearing this sound will make you feel happy, too.

Chickens and Other Animals

Chickens get along well with other pets and livestock. You can pasture them with sheep, goats, cows, or horses, but if the chickens have access to roosting on the manger or in the hay storage area, they will foul the hay for the other livestock.

Keeping chickens with ducks or geese is not a good idea. Waterfowl like it wet, and chickens need to stay dry to be healthy. Chickens shouldn’t be kept with pigs or turkeys, either, because of the possibility of exchanging diseases.

Chickens get along with dogs and cats, provided the pets are properly trained. The best way to train a pet is to introduce it to chickens as a puppy or kitten, to which chickens look big and scary — something to stay away from. Adult cats need to be watched around baby chicks, and all dogs must be watched around chickens. Discourage your dog from playing with your chickens, as dogs tend to play rougher than chickens can withstand. Many a chicken has been killed by a family dog that didn’t mean it.

Banding

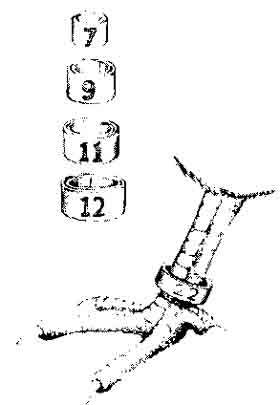

When all the chickens in a flock look alike, it’s a good idea to band them so you can tell them apart. Thin spiral leg bands may be used for whole flock identification. If, for example, you want to keep track of your chickens according to the year they were hatched, use a different color band each year.

To keep track of individual birds, such as for mating purposes, use numbered leg bands. My chicken entered in an exhibition is required to wear a numbered band for identification.

Leg bands are sold through poultry supply catalogs and at some feed stores. Be sure to purchase the right size band for your breed:

• Number 7 (7/16”) fits most bantams.

• Number 9 (9/16”) fits hens of the light breeds, such as Leghorn and Ancona.

• Number 11 (11/16”) fits cocks of the light breeds and most dual-purpose chickens, such as Wyandotte and Plymouth Rock.

• Number 12 (12/6”) fits cocks of the heavy breeds, such as Jersey Giant and Cornish.

Numbered leg bands help you identify chickens in your

flock.

Catch and Carry

The easiest way to catch a chicken is to go out after dark, when the chicken is asleep, and pick it off its perch. If you need to catch a chicken during the day, you’ll be happy if yours are tame enough for you to walk right over and pick them up. A chicken that isn’t tame will stay just out of reach or run away from you. In that case, try to trap it in a corner, which is easier if you have help. Once you start to catch a chicken, don’t give up or you’ll only teach the bird to evade you in the future.

If you will have occasion to frequently catch chickens during the day, invest in a crook or a poultry net. The crook lets you snare a leg. With a net, you can snag the whole bird, if you’re quick. Both devices are available from poultry suppliers.

After you have caught a chicken, hold it for a moment until it calms down. Stroke its neck and wattles to let it know you mean no harm. Cradle the chicken in one arm while you hold its legs with the other hand. When carrying more than one chicken, you can turn them upside down and use their legs as handles. Hold on to both legs or the chicken may churn around, scratching you with its claws until it gets away.

To catch a chicken with a crook, slip the hook over one

leg.

Transporting

Chickens may be safely transported in anything from a paper hag to a pet carrier, as long as the following conditions are met:

• The chicken can’t get out.

• The container has no sharp edges or other injurious protrusions.

• The container is large enough for the bird to stand up and move around.

• The container is not so large that the bird can hurt itself flying about if it becomes frightened.

• The chicken gets enough air but is protected from drafts, cold, and rain. A stock rack or wire cage on the open bed of a pickup truck, for example, is not suitable for transporting chickens. A car trunk may not be suitable if it accumulates carbon monoxide fumes.

• The chicken has access to drinking water, if not in transit, at least during occasional stops.

• You don’t leave the chickens in a car or truck during hot weather.

Training

All chickens should be trained to some extent. They should at least learn to remain calm when you move among them. Some people train their chickens to come when they are called and to stand calmly so they may be picked up and handled. This type of training takes a great deal of time. If you are interested in exhibiting your chickens at poultry shows, you must be willing to devote time to their training. Flighty chickens that are afraid of people and of being handled don’t stand a chance of winning prizes.

Poultry shows are sponsored by fair boards and various local clubs and may be sanctioned by the American Poultry Association, the American Bantam Association, or both. The show’s premium list tells you what organization, if any, has sanctioned the show, what prizes are being offered, what rules must be followed, and which classes will be shown.

Once you decide which of your chickens qualify for the show you intend to enter, they must be conditioned and trained. Conditioning involves making each bird look its best, and must be done anew before each show. Training teaches a bird to remain calm around people and to accept being handled. It may be started at any time during the bird’s life, but the younger the chicken, the easier it will be to train.

Training involves handling each individual bird two or three times a day. Approach slowly, and if the chicken seems frightened, pause until it calms down. Reach across the bird’s back and place one hand over its far wing, at the shoulder. Place your other hand under the breast, with one leg between your thumb and index finger and the other between your second and third fingers. Your index finger and second finger should be between the bird’s legs. The bird’s breastbone, or keel, will rest against your palm.

Gently lift the chicken and hold it quietly for a moment, then remove your hand from its wing. Let it sit in your hand another moment. Turn it to examine its comb and wattles. Open each wing. Initially keep the bird facing toward you; if you face it away, it may try to escape. After a few moments, gently put the bird down on its feet, pause before letting go, then slowly move away. Repeat this procedure often enough and your chickens will soon be crowding around you, eager for your attention.

Next: Housing Chickens

Prev.:

Purchasing Chickens