Selection Criteria

The variety of models available to practitioners is unlimited. Picking a selection model depends on the nature of the organization. For example, factors such as industry, organization size, risk aversion level, technology, competition, markets, and management style may strongly influence the form of the model used to select projects.

In the past, financial criteria were used almost to the exclusion of other criteria. However, in the last two decades we have witnessed a dramatic shift to include multiple criteria in project selection. Succinctly, profitability alone is simply not an adequate measure of contribution; however, it is still an important criterion. A detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this text; however, two financial models are briefly mentioned here to give the reader a sense of the nature and potential problems of financial models.

1. The payback model measures the time it will take to recover the project investment. Shorter paybacks are more desirable. Payback is the simplest and most widely used model. Payback emphasizes cash flows, a key factor in business. Some managers use the payback model to eliminate unusually risky projects (those with lengthy payback periods). The major limitations of payback are that it ignores the time value of money, assumes constant cash flows for the investment period (and not beyond), and does not consider profitability.

2. The net present value (NPV) model uses management's minimum desired rate of return discount rate (for example, 20 percent) to compute the present value of all cash inflows and outflows. If the result is positive, and the project meets the minimum desired rate of return, it is eligible for further consideration. Higher positive NPV's are desirable. Table 1 (below) presents simple examples of the payback and NPV models.

From Table 1 the payback method suggests project B because it has a payback of 3.3 years. However, the NPV model rejects both projects, which have negative present values of -$346,130 and -$61,620, because it considers the time value of money. The NPV model is more realistic because it considers the time value of money, cash flows, and profitability. This example demonstrates the major shortcoming of the payback model and why model selection is important.

Models such as payback and NPV represent one criterion useful in screening alternative projects. However, financial criteria alone obviously cannot serve as a project screening process that establishes a clear link between strategy and project selection.

|

Table 1: FINANCIAL PROJECT SELECTION CRITERIA Given data for two potential projects: |

|||

|

Project A |

Project B |

|

Cost of project |

$720,000 |

$600,000 |

|

Estimated annual cash inflow |

$125,000 |

$180,000 |

|

Estimated useful life of project |

5 years |

5 years |

|

Required rate of return |

20% |

20% |

|

Payback Period |

|

|

|

Payback Period = Investment/Annual net savings |

= 5.8 years |

= 3.3 years |

|

Rate of return (a) |

17.4% |

30.0% |

|

NPV (Net Present Value) |

|||

Present value of annual net cash inflows Project A $125,000 x 2.991 (b) Project B $180,000 x 2.991 Investment NPV |

$383,870

(- 720,000) (-$346,130) |

$538,380 (- $600,000) (-$ 61,620) |

|

Payback Project A -- 5.8 years; reject, longer than life of project (5 years) Project B -- 3.3 years; accept, less than 5 years and exceeds 20% desired rate of return Net present value Reject both projects because they have negative net present values: a. The reciprocal of payback yields the average rate of return (e.g., 125/720 x 100 = 17.4%). b. Present value of an annuity of $1 for 5 years at 20 percent. These values can be found in annuity tables of standard accounting and finance texts. |

|||

Other factors such as researching a new technology, public image, ethical position, protection of the environment, core competencies, and strategic fit might be important criteria for selecting and prioritizing projects. The trend toward using multiple screening criteria models is quickly gaining acceptance-especially in project-driven organizations. One impetus supporting this trend was the advent of Y2K projects (the millennium date bug).

Selection Process

Under rare circumstances, there are projects which "must" be selected. "Must" projects are those which must be implemented or the firm will fail or will suffer dire consequences. For example, a manufacturing plant must install an electrostatic filter on top of a smoke stack in six months or close down. Other examples could be a large software firm must open its software architecture to allow other competing software to be compatible and to interact with Y2K projects. Any project placed in the "must" category ignores other selection criteria. A rule of thumb for placing a proposed project in this category is that 99 percent of the organization stakeholders should agree that the project must be implemented; there is no perceived choice but to implement the project. All other projects are selected using criteria linked to organization strategy. A project selection process which uses multiple screening criteria is discussed next.

Project Proposals

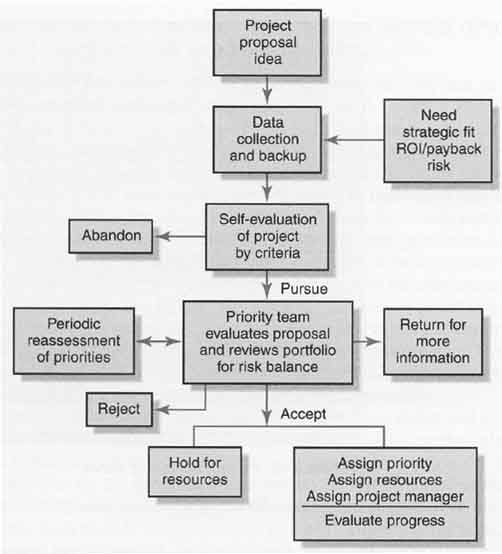

Suggestions for projects come from many internal and external sources. It is a rare organization that does not have more project proposals than are feasible. This is especially true in project-driven organizations. Culling through so many proposals to identify those that add the most value requires a structured process. Fig. 1 shows a flow chart of a screening process, beginning with the creation of an idea for a project. Data and information are collected to assess the value of the proposed project to the organization and for future backup. If the sponsor decides to pursue the project on the basis of the collected data, it is forwarded to the project priority team (or sometimes a project office). Given the selection criteria and current portfolio of projects, the priority team rejects or accepts the project. If accepted, the priority team sets implementation of the project in motion.

Priority Team Role

The role of the priority team includes more than accepting or rejecting project proposals on the basis of selected criteria. The priority team is responsible for publishing the priority of every project and ensuring that the process is open and free of power politics. For example, most organizations using a priority team or project office use an electronic bulletin board to disperse the current portfolio of projects, the current status of each project, and current issues. This open communication discourages power plays. In addition, the priority team is responsible for balancing the portfolio of projects for the organization. Hence, a proposed project that satisfies most criteria may not be selected because the organization portfolio already includes too many projects with the same characteristics-for example, project risk level, use of key resources, high cost, non-revenue producing, long durations. Such projects may be put on hold. Over time the priority team evaluates the progress of the projects in the portfolio. The priority team is also responsible for reassessing organizational goals and priorities and changing priorities if conditions dictate. How well this whole process is managed can have a profound impact on the success of an organization.

Fig. 1: Project Screening Process

Selection Criteria

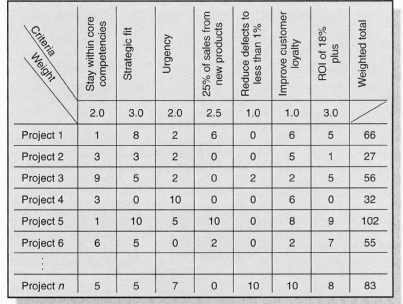

Selection criteria need to mirror the critical success factors of an organization. For example, 3M set a target that 25 percent of the company's sales would come from products fewer than four years old versus the old target of 20 per cent. Their priority system for project selection strongly reflects this new target. On the other hand, failure to pick the right factors will render the screening process "use less" in short order. Fig. 2 represents a hypothetical project scoring matrix. The screening criteria selected are shown across the top of the matrix (stay within core competencies ... ROI of 18 percent plus). Management weights each criterion (a value of 0 to a high of, say, 3) by its relative importance to the organization's objec tives and strategic plan. Project proposals are then submitted to a project priority team or project office.

Fig. 2: Project Screening Matrix

Each project proposal is then evaluated by its relative contribution/value added to the selected criteria. Values of 0 to a high of 10 are assigned to each criterion for each project. This value represents the project's fit to the specific criterion. For ex ample, project 1 appears to fit well with the strategy of the organization since it is given a value of 8. Conversely, project 1 does nothing to support reducing defects (its value is 0). Finally, this model applies the management weights to each criterion by importance using a value of 1 to 3. For example, ROI and strategic fit have a weight of 3, while urgency and core competencies have weights of 2. Applying the weight to each criterion, the priority team derives the weighted total points for each project. For example, project 5 has the highest value of 102 [(2 x 1) + (3 x 10) + (2 x 5) + (2.5 x 10) + (1 x 0) + (1 x 8) + (3 x 9) = 102] and project 2 a low value of 27. If the resources available create a cutoff threshold of 50 points, the priority team would eliminate projects 2 and 4. (Note: Project 4 appears to have some urgency, but it is not classified as a “must” project. Therefore, it is screened with all other proposals.) Project 5 would receive first priority, project n second, and so on. In rare cases where resources are severely limited and project proposals are similar in weighted rank, it is prudent to pick the project placing less demand on resources. Weighted multiple criteria models similar to this one are rapidly becoming the dominant choice for prioritizing projects.

In summary, centralized project priority systems support a holistic approach to linking organizational projects to organizational strategy. The system is proactive rather than reactive. The project portfolio represents a process for controlling the use of scarce resources and balancing risk. Regardless of the criteria used for selection, each project should be evaluated by the same criteria. The project priority system ties re source requirements directly to resource availability. Enforcing the project priority system is critical. Keeping the whole system open and aboveboard is important to maintaining the integrity of the system. For example, communicating which projects are approved, project ranks, current status of in-process projects, and any changes in priority criteria will keep people from bypassing the system. Project-driven organizations are integrating organizational goals and strategy with projects using a portfolio of projects selected by a proactive project priority system.