Our built environment is changing the world significantly and , it would seem, irrevocably Global climate change and the steady depletion of essential natural resources are making the news More devastating natural disasters, such as Hurricane Katrina in 2005, and painfully high energy costs may be an inevitable part of our future, and residential construction is partly to blame. More than a million single family homes are built every year in the United States alone. All of those houses consume an inordinate amount of natural resources and energy. Maybe that’s why green building seems to be taking root, not as a passing fancy but as a fundamental change in how and why we build the houses we live in.

What we alternately call green building or sustainable building is a way for people to make a positive difference in the world around them—if not reversing, then at least reducing the impact of humankind on the planet. Not coincidentally, it has its own practical rewards on a scale that all of us can immediately understand. If becoming model citizens of Planet Earth is too much to get our arms around, living in healthier, more comfortable houses that are less expensive to operate and last longer is certainly an attractive idea. Who wouldn’t want to participate in something like that?

The Green Factor Green building encompasses every part of construction, not just the house itself but everything around it and how the house and its occupants relate to the community around them. In theory, it can seem simple In practice, It can get complicated At its most basic, green building is a tripod of three interrelated goals: Energy efficiency, the cornerstone of any green building project. A well-designed and green-built home consumes as little energy as possible and uses renewable sources of energy whenever possible. Lower energy use not only saves homeowners money but also has broader societal benefits, including fewer disruptions in energy supplies, better air quality, and reduced global climate change. Conservation of natural resources. Conventional building needlessly consumes large quantities of wood, water, metal, and fossil fuels there are great varieties of effective building strategies that conserves natural resources and provides other benefits, such as lower costs |

|

Green building is ultimately about the relationship of a house and its occupants to the world around them. It’s a process of design and construction that fosters the conservation of energy and other natural resources and promotes a healthy environment. |

In essence, that’s what green building is about. It’s not a scorecard where we rack up the number of recycled building materials we use, nor is it a requirement to buy a roof’s worth of solar panels or put a wind generator up in the backyard. Green building might include some or all of these things, but it’s a lot more than that. Green building is a systematic approach that covers every step of design and construction from land use and site planning to materials selection, energy efficiency, and in door air quality. All of this will be covered, step by step, in the sections that follow.

Green Is No Longer on the Fringe

Green is hot. According to a survey conducted by McGraw-Hill Construction, demand for green building had outpaced supply by early 2007 as home buyers looked for greater energy efficiency. The National Association of Home Builders (NAHB), a trade group not known for making wild predictions, now believes we’ve reached the tipping point when half or more of its members are incorporating green features into the homes they build. Even the modular housing industry is getting into the act with a growing list of designers coming up with houses that embrace the goals of sustain able building, not simply fast construction.

Green building shows every sign of becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy: The more people are exposed to the benefits of green homes, the more green homes will be built.

Coast-to-coast, the home-buying public is asking for green features from their architects and builders.

So where did all this start?

It really began in Austin, Texas, in 1992 when the city’s green building program won a sustainable development award from the United Nations’ Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. That put green building on the map, and builders working on the fringes of conventional construction used the healthy-living, energy-saving objectives of green building as a unifying theme. Over the next several years, alternative building techniques such as straw- bale, rammed earth, and adobe construction received a lot of press.

Interiors built to sustainable building standards don’t have to look odd. These cabinets are made from panel products that don’t off-gas toxins and are manufactured with materials that can be harvested sustainably. Water-based and natural finishes keep occupants healthier than those loaded with volatile organic compounds. The wallpaper is made from renewable cork. |

By 1996, the Denver Home Builders Association was developing the first private sector green building program in the country. Although it met with great resistance, the board approved the plan by a single vote. At the same time, Boulder, Col., became the first city in the country to make sustainable building part of its city code. If you wanted a building permit, you had to have 50 “green points” on the permit application. Both the Denver and Boulder programs got the attention of the construction industry as well as city officials across the country. Cities from Atlanta to Seattle launched green building programs, then home builder associations around the country picked up on Denver’s example. By 1999, there were more than 50 local programs countrywide.

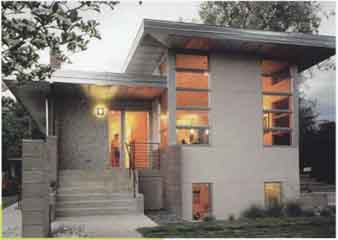

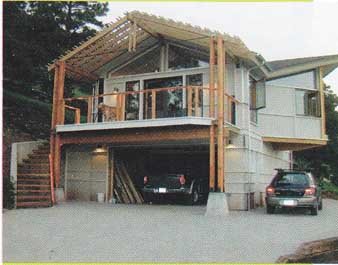

Alternative designs of the 1970s may have been

inexpensive to build and heat, but they lacked a diversity of design that

turned of f many potential converts. This house incorporates structural

insulated panels, insulating concrete forms, and other green features yet

looks entirely contemporary.

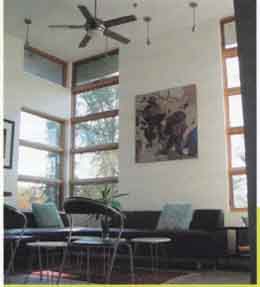

Smart planning can include the placement of windows

for solar gain, thereby reducing energy bills, and using concrete as a finish

material on floors. Minimizing carpeting reduces the threat of mold and allergens. A ceiling fan and operable windows aid ventilation.

Lots of Green, Few Common Standards

There were plenty of green building programs, but not much common ground. Each of the country’s local programs had its own definitions of what it meant to be green, and builders working under more than one of the programs could easily be confused. In the Boulder, Colorado, area alone, for example, builders in the late 1990s could choose from among four separate green programs. The NAHB soon started thinking about what production homebuilders needed to know, and the association later published its own set of guidelines. They are just that—guidelines that may be adopted by builders as they see fit. Local or statewide programs scattered elsewhere across the country may follow the NAHB Green Building Guidelines lead of suggesting without requiring, or they may set measurable performance standards. The Energy Star program of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has included indoor air quality as part of its energy-saving initiative. MASCO, a large conglomerate of building product manufacturers, has its Environments for Living (EFL) program that certifies builders at progressive levels of home performance (see www.eflbuilder.com).

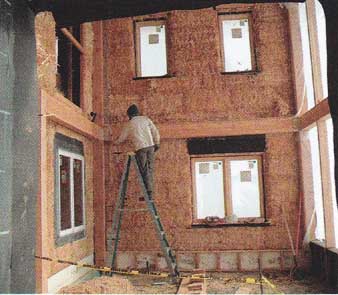

BUILDING WITH STRAW Straw bale construction will probably never be mainstream but it does satisfy at least three important goals for green building straw is a renewable resource that can be harvested locally it s relatively inexpensive and straw bale walls have high R values for energy efficiency. Straw can be used as infill—meaning a structural framework actually carries building loads—or the bales can be formed into structural walls without any additional framework. Once the bales have been stacked into walls and pinned together they re covered with wire mesh and finished with stucco to make them weather tight and durable. It can take several hundred bales of straw to make a house but the raw material is an agricultural waste product that can come from any one of several crops—wheat oat barley and rye among them Some 200 million tons of straw are produced in the U S annually so there’s plenty of it available.

|

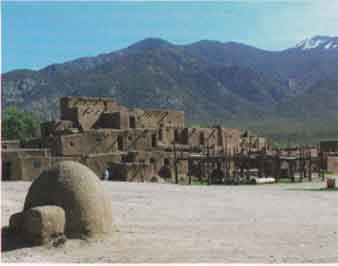

RAMMED EARTH and ADOBE Both rammed earth and adobe houses seem nearly ideal from a green point of view and , in many ways, they are. The appeal of both techniques is that the Earth itself is the basic raw material for the building envelope. It would be hard to top that on a scale of sustainability. Traditional adobe houses are made from earthen bricks that have dried in the sun and are laid in courses to form walls. Modern versions can be stabilized with cement. The gently rounded contours and thick walls of these houses are an architectural trademark of the southwestern U.S. and Mexico. Because building materials can be taken directly from the site they’re inexpensive, and adobe has high mass, although not necessarily a high R-value. There’s probably no reason that adobe houses couldn’t be built outside their traditional geographic stronghold. But on a practical level, you’ll also need hot, sunny weather and the right kind of soil to make the bricks, as well as experienced builders who know how to work with the material. You’re not likely to find those conditions in Tacoma, Cincinnati, or Boston. If you have adobe bricks trucked in, it’s going to get very expensive, Rammed earth is another green-friendly building technology in which soil mixed with a small amount of cement is compacted with hydraulic tools in forms to create walls up to 2 ft. thick. Walls are extremely heavy—100 lb. or more per sq. ft.—so these houses call for sturdy concrete stem-wall foundations. Building a rammed earth home is not a beginner’s game. It takes specialized equipment as well as know-how, and the labor-intensive process isn’t inexpensive. Rammed Earth Development, a Tucson, Arizona-based company specializing in this technique, estimates that a rammed earth house starts at nearly $200 per sq. ft. Ironically, even though walls are made from earth, not any kind of soil will do. Rammed Earth says site soil is used only rarely because most of it doesn’t have the right mix of ingredients. It’s actually cheaper to buy screened fill, according to the company. Both building techniques are appealing for their use of natural materials, if not their inherent beauty. But a variety of factors is likely to keep them confined to a limited geographic region. Good sources to learn more about it include Rammed Earth’s web-site (www.rammedearth.com) and another for a California company, an early practitioner of the craft (www.rammedearthworks.com).

|

A way out of this morass arrived in 2000 in the form of the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design program (or just LEED for short), a set of specific, measurable building standards developed by the U.S. Green Building Council for commercial construction. By 2006, it had evolved into a pilot program called LEED for Homes that was headed for full-scale adoption sometime in 2007.

To date, LEED is the only national green building program that puts the exact requirements for earning green status in writing and requires independent verification that buildings are constructed that way. and this is key.

Overtime, consumers are almost certain to become far more educated and a lot less tolerant of slippery definitions of green building: “Is that house really green?” they’ll ask. “Prove it.” Without published standards that can be certified in the field by independent inspectors, it will be very difficult for builders to show homebuyers they’re getting what they paid for.

In spite of, or maybe because of, the proliferation of green building initiatives and published guidelines, there is still ample room for confusion among builders who want to build green. Not only are there a number of programs to choose from, but their different criteria can compete with one another. For example, durability of building components is an important consideration because it’s one way of reducing waste. Vinyl siding lasts a long time but there are concerns about dioxin and other dangerous by-products that result from the manufacture and incineration of polyvinyl chloride. So, can a house built to sustainable standards include vinyl products? If so, which ones are acceptable and which are not?

House size poses another such dilemma. Suppose a house built for two people includes a variety of recycled products and energy-saving building techniques or is even capable of operating completely off the grid—but it’s 6,000 sq. ft. and cost $500 per sq. ft. to build. It uses far more resources than an average-size house, and certainly far more than is necessary for a single couple. Can such a house really be considered green?

There may be no perfect answer to these questions, only a process to balance competing interests. For builders and consumers alike, it can be a bewildering process.

MYTH #1: GREEN BUILDINGS ARE FOR TREEHUGGERS Yes, committed environmentalists do like green building. But green building is not for extremists. It’s going mainstream. According to an estimate from the Environmental Home Center in Seattle, the overall market for sustainable building materials is about $20 billion a year, and it s expected to grow more than 10 percent annually. That makes it big business. Why are a growing number of consumers buying into green building? Rising energy prices are certainly a big reason. Consumers are beginning to realize that sustainably built houses mean lower heating and cooling costs. Health is another major reason: Our health and well-being are notably affected by the large amount of time we spend indoors. According to the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, more than 38 percent of Americans suffer from allergies. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, the number of asthma cases grew by 75 percent from 1980 to 1994—to more than 17 million. Since when is saving money and enjoying good health an issue for any particular cultural or political minority? MYTH #2: GREEN BUILDING IS TOO EXPENSIVE Some green building components do cost more, But many cost less. When thinking green is part of the initial planning process, it’s easier and less expensive to incorporate features that significantly lower operating and maintenance costs. For example, passive solar design coupled with high-performance insulation can make a conventional furnace or boiler unnecessary. Orienting a house to take advantage of solar energy does not in itself cost a penny more than standard construction. Adding a few windows and investing in insulation does cost money, but the rewards on the other side of the ledger are far more substantial, initially and over the life of the house. Many builders have found that the real cost is in learning new techniques. Products themselves are becoming more readily available and more affordable as major manufacturers develop new lines to meet consumer demand. MYTH #3 GREEN BUILDING IS UGLY Green buildings do not have to look like yurts. True, a yurt can have its own beauty, but understandably not everyone wants to live in one. Uniformity or plainness of design is one factor that hampered wider acceptance of alternative building practices back in the 1970s (let’s face it, some of those houses were just plain ugly). But a green home can look like any other house: colonial, modern, southwest, ranch—you name it. Even on the inside, green homes can be just as varied in design, just as stunning, as any conventional home. On another level, green buildings are inherently more beautiful because builders and homeowners take the time to understand how the house works and what materials will work better than conventional products. Reclaimed wood, recycled glass, certified lumber—the list of beautiful green materials is very long indeed. |

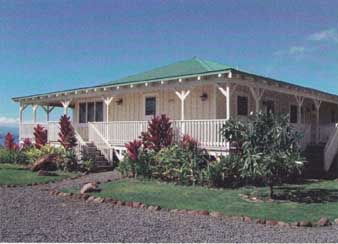

A green house that doesn’t necessarily look it:

This pleasant bungalow-style house in Hawaii uses long-wearing steel rooting

made to facilitate the addition of photovoltaic panels at a later date.

The bungalow design with deep overhangs and protected porches suits the

climate perfectly.

Increasingly savvy home buyers want assurances that

their new home is “green.” A passive solar design with south-facing glass,

formaldehyde-free cabinet components, and flooring from sustainable sources

can contribute to certification.

Increasingly savvy home buyers want assurances that

their new home is “green.” A passive solar design with south-facing glass,

formaldehyde-free cabinet components, and flooring from sustainable sources

can contribute to certification.

GETTING BIGGER

In 1973, the average new single-family home in the U.S. measured 1,660 sq. ft. By 2005, the size had risen to 2,434 sq. ft.—an increase of 46 per cent. That still may seem modest, but in some parts of the country, huge houses are the norm. In Boulder County, Colorado, for example, the average new house is 6,000 sq. ft. In Aspen, Col., it’s 15,000 sq. ft.

Dealing with the World around Us

Political history and diversity aside, the nation’s green building programs share a common goal—building houses that recognize some uncomfortable realities in the world around us. Some of the most important fundamentals of sustainable building—energy and resource conservation and indoor air quality—are a reaction to a world very different than it was a decade ago. Seen in this light, sustainable building is a practical response to a variety of issues that affect us all.

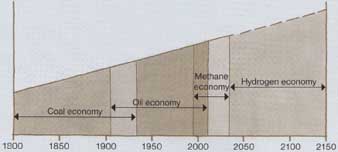

Energy supplies are peaking

Let’s start with something known as “peak oil,” the hypothetical moment when the world has pumped the maximum possible number of barrels per day out of the ground. After that, oil production starts to decline. The U.S. hit its peak in the mid-1970s. Many oil geologists believe the world will hit peak production sometime in the next decade. Whether we reach that point in two years or 10 years, we are nearing the end of the cheap oil era. That’s alarming enough on its own, even more so when you consider that buildings are responsible for at least 40 percent of all energy consumption in the U.S.

As recently as the mid-1990s, energy experts assumed there was enough natural gas to serve as the transitional fuel from a petroleum economy to a hydrogen economy. It is a near- perfect fuel—abundant, domestic, clean-burning, and relatively inexpensive. As a result, turbines that burned natural gas were built to augment many coal-fired plants in the U.S. Then the domestic supply of natural gas began to decline.

Buildings contribute over 40 percent of the total greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, more than either industry or transportation alone.

Gas wells stopped producing but demand kept growing with the construction of both buildings and power plants. From 2002 to 2004, natural gas prices doubled in much of the U.S. In some markets, prices went up even higher.

Energy Supply Gap

|

The U.S. started to import natural gas from Canada and Mexico through new pipelines. Today, we are close to using the total volume of available gas from all North American sources. In some parts of the country, there are not enough pipelines to meet the demands of growing communities.

Oil is easily shipped in tankers. But natural gas must be compressed, liquefied, and shipped at very low temperatures in huge refrigerated tanks aboard a ship. Due to the potential danger in handling liquefied natural gas (LNG), there is tremendous resistance to installing off-loading facilities in U.S. ports. As a result, we don’t have the capacity to import much LNG. It, too, will become increasing expensive and harder to get.

Because of these and other factors, energy conservation is a cornerstone of green building. Cutting energy use has an obvious and immediate effect on how much it costs to heat and cool a house. Not worried about how much oil is left in Saudi Arabia? OK, green building can be about your heating bill next winter.

Climate change means a tougher environment

Scientists may argue about the ultimate cause, but climate change is certainly upon us. Most people recognize it as ‘weird” weather. Every where in the world, local weather patterns change in unpredictable ways. There are more intense hurricanes like Katrina, longer droughts like those in East Africa, unheard of floods in New England and Ohio, and more violent weather events such as tornados.

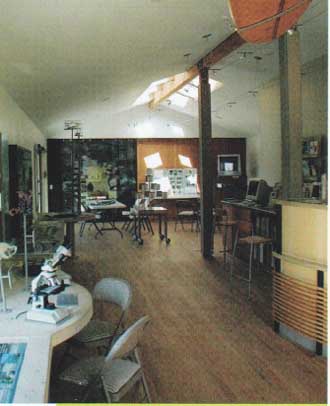

This office was made from a variety of green building

products including structural insulated panels and engineered structural

beams but cost only $75 per sq ft. Located in Colorado, its radiant

floor heating is driven by a conventional water heater.

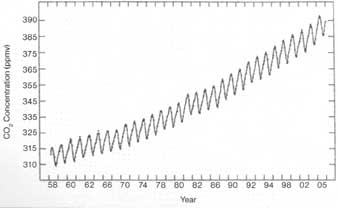

Most experts lay the blame on higher concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO in the atmosphere. It’s called a “greenhouse gas” because it traps heat that would otherwise be radiated back into space. and the problem feeds on itself. As more 002 builds up, it in turn traps more heat, which accelerates the process. Take, for example, what happens in the arctic when ice melts due to higher global temperatures. As the ice cap melts, more of the dark ocean is exposed and more heat is absorbed, which helps to melt more ice. This “positive feedback loop” is a cycle: more heat, less ice, and a faster rate of melting.

Green building’s response is to cut the amount of carbon dioxide produced directly and indirectly by encouraging the use of renewable energy sources where possible and recycled products or products that take less energy to produce. The result is a smaller “carbon footprint.” This is why zero- energy homes, houses that produce as much electricity as they consume, are springing up across the country.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions

|

Water isn’t boundless, either

Roof-mounted solar panels are one way of reducing

the consumption of fossil fuels and shrinking the “carbon footprint” of

a house.

The U.S. uses water so flagrantly that many of us may not think of it as a finite resource. After all, two-thirds of the planet is covered in water and it’s raining somewhere all the time. What few of us realize is that less than 1 percent of the planet’s water is drinkable. Most of the earth’s fresh water is frozen in the polar ice caps. What we have been living on is surface water, aquifer water, and fossil water.

Surface water, found in lakes, rivers, and streams, is confined primarily to the region where it is found—the Great Lakes, for instance, or the Colorado River. Aquifer Water, replenished by rainfall that seeps into the earth, is what we tap into when we drill wells in drier areas. Fossil water is like oil: It will never be replenished. All three are being challenged from either pollution or overuse.

As climate change becomes more intense, rainfall patterns around the world will change. Some regions will get more, some significantly less. In the U.S., predictions are that the western U.S. will become increasingly drier over the next 20 years with the possibility of a drought to rival the one that produced the Dust Bowl in the 1930s. The huge but shallow Ogallala Aquifer under the Great Plains from the Dakotas to Texas is dropping at the rate of 30 ft. per year, and the less it rains the faster it is drawn down. Northwest China is one of the four largest grain-producing areas in the world and feeds China today. But it runs on fossil water, which may be completely gone in the next five years. What happens then?

Decreasing water supplies, along with rapidly rising energy prices, will bring higher food prices. Competition for food will also lead to increased conflict over food-growing areas and water sources.

Seen in context, those 10-gal-a-minute bathroom shower spas may not look quite as appealing. Water conservation becomes an obvious component of green building and goes a long way toward explaining an emphasis on water-saving toilets, low-flow showerheads, and landscaping that doesn’t require much watering.

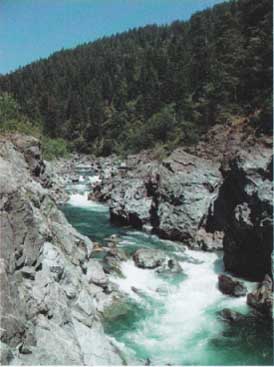

Many Americans have taken clean water for granted,

but increasing pressure is taking its toll Aquifers once thought to be nearly

limitless are dropping rapidly as a growing population competes for a finite

resource.

Other natural resources on the wane

Structures — residential, commercial, and industrial — account for 40 percent of all natural resources consumed in a single year. Yet construction of the average 2,000-sq-ft. house also yields 50 to 150 cu. yd., or 8,000 to 12,000 lb., of construction waste. Most of that ends up in landfills.

MYTH #4: GREEN BUILDING DOESN’T WORK The list of consumer concerns about how well a green building works is long: “The low-flow showerheads leak.” “Bamboo flooring warps easily.” “Zero-VOC paint doesn’t cover walls as well as the paint I’ve always used.” “Compact fluorescent lights give off a weird bluish glare.” Some complaints have been justified, but these concerns tend to focus on exceptions rather than on the big picture. In general, sustainably built houses tend to be more energy efficient, more durable, and less costly to maintain. That said, some green products have had quality issues. But keep in mind that conventional products have also had quality concerns, not to mention unacceptable effects on our health and the environment. Many green products were designed to do something better than a conventional product, not specifically because they could be considered “green.” Inevitably, if a green building product does not work, market forces will force it off the shelves, just as under performing conventional products are gradually abandoned in favor of something else. Today, manufacturers of low-flow showerheads, bamboo flooring, and low-VOC paint are creating reliable products. Although the industry has had some growing pains, in the end green building is simply better building. |

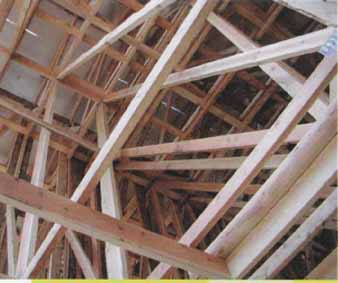

Construction debris from a single house can be measured

by the ton, but some builders are getting smarter about recycling waste and reusing building components. Dismantling this house provided a wealth

of material that could be reused and kept recyclables out of the landfill.

Too much lumber can compromise the resource efficiency

of a house.

RECYCLING PAYS Builders may look on jobsite recycling as a pain in the neck. It’s much easier, isn’t it, to have a big Dumpster dropped at the site? By the time the house is done, the Dumpster is full and everyone goes home happy. That may be standard practice in many parts of the country, but finding ways to recycle waste at the jobsite can ultimately be much cheaper, as builders in some communities have already discovered. In Portland, Oregon, disposal fees for garbage were about $71 per ton in 2005 (plus a $7.50 transaction fee). Most construction waste could be dropped off at a recycling center for fees that topped out at $35. In the very worst-case scenario, recycling cost half as much as throwing it in the Dumpster, probably less. |

FACT: Americans make up 5 percent of the world’s population but use 25 percent of the world’s resources.

Landscaping that promotes natural plants and uses

water wisely has twin benefits: houses look as if they fit the landscape

more comfortably and water use can be cut dramatically.

That rate of consumption simply isn’t sustainable. It amounts to using 1.2 planets’ worth of resources to take care of just one planet of about 6 billion people. When we hit 8.5 billion people in the year 2025 or so, those resources will have to be stretched a great deal thinner.

Wood is the most renewable of resources used in the building industry, and we use plenty of it for new houses. An increasing amount of it comes from tree plantations, not real forests, hence a green emphasis on making supplies go further and not converting natural forests to tree farms. Advanced framing techniques and the use of structural insulated panels, engineered wood, and Forest Stewardship Council certified—lumber can all help. Those practices are explained in section 5.

A variety of metals are also used in building—copper pipe, steel framing and structural supports, aluminum flashing, and metal roofing. Three billion tons of raw materials are turned into foundations, walls, pipes, and panels every year. Using materials in their highest and best use is critical. Increasing the proportion of recycled materials helps reduce waste.

Green building is, above all else, applied common sense. Yet the building industry is agonizingly slow to change, partly because it takes time for new technologies and building practices to filter into the field and partly because builders, many of whom run small businesses are reluctant to take risks on “new” ideas that have not been proven. They have their reasons: polybutylene pipe that sprang leaks, hardboard siding that rotted in humid climates, and a variety of other products that never quite lived up to the hype. They cost builders millions in claims and callbacks. Even so, sustainable building practices, designing and building homes using a whole system approach, and the products that go with them will eventually overcome those misgivings. It’s not a gimmick. It’s just good building.

Best Practices • Test your market and set priorities for what s important to homebuyers in your area. It might be energy conservation, indoor air quality, water conservation, or something else specific to your community or region. • If sustainable building is something new to you, try not to do everything at once. Choose a priority and get good at that Then branch out • Get your staff and your subs on board with what you re trying to accomplish. Once everyone realizes that building green is important to the future of the company will probably have good id of their own to contribute. |

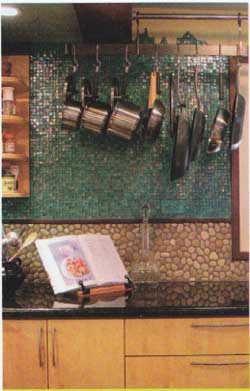

As interest among consumers increases, so do the

number of reliable and attractive green building products. Natural finishes,

tile made from recycled glass, and cabinets constructed of bamboo contribute

to the look of this kitchen.

Next: The House as a System

Prev: