There are whole books on how to use a map and compass, but no one ever learned how entirely from a book. You have to use them in the field. All I can do is get you started.

The only kind of map I consider worth carrying in the wilder ness is a topographic map (“topo” map). This is a government map, prepared by the United States Geological Survey, which shows not only lakes, streams, roads and trails, but also relief— the hills and valleys. It shows relief by means of contour lines— lines that are a constant elevation above sea level, like high-water marks on a reservoir that has been drawn down. In mountainous areas, where backpacking involves a lot of ups and downs, I consider the contours essential.

You can get topographic maps for most of the United States at a scale of 1:24,000, which is about 2.6 inches to the mile. These are sometimes called “7 1/2-minute” topographic maps because each of them covers an area of 7 1/2-minutes (1/8 degree) of longitude and 7 1/2 minutes of latitude. The area within a Geological Survey map is called a quadrangle. In the latitude of Central California or North Carolina, a 7 1/2-minute quadrangle is about 7 miles east- west by 9 miles north-south. Farther north, the east-west mileage is less because a degree of longitude becomes shorter in miles as you go toward the North Pole.

Once you learn how to use a topographic map and a compass, you can’t get lost. If you were parachuted down somewhere in the mountains and given the topographic map of the area you were in, you could pinpoint your location—provided there were some distinctive landforms in sight—and you could walk to any other place on the map.

Before you start your trip, buy the topographic map(s) that covers it. Get your map at a backpacking store or by mail from the U.S. Geological Survey.

On the map, find your trailhead and your route. Study the surrounding country on the map to get some idea of what it is like. Then fold the map to a size that will fit your pocket, and put it in a plastic sack or envelope to keep it clean and dry.

After some experience you will know about how much distance—horizontal and vertical—you can cover in a day. You can measure miles on the topographic map by estimating or by using a map wheel, which you can get at a backpacking store or a map store for a few dollars. Since the map doesn’t show the trail’s small irregularities, the trail on the ground is longer than the trail on the map. To approximate true mileage for mountainous country, add to the length of trail on the map, as measured by the wheel or as estimated, 20 percent of the distance where there are no switchbacks and 100 percent of the distance where there are switchbacks. To determine the number of feet of ups and downs, count the contour lines that your route crosses and multiply by the contour interval, which is always given on the map.

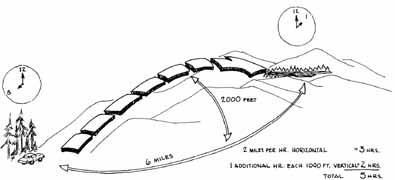

How long will it take to walk the route you have planned? A

rule of thumb that works out for many though not all backpackers is:

- 1 hour of hiking for every two horizontal miles

- 1 additional hour for every 1000 feet of ascent or steep descent

For example, if your day’s plan is to walk 6 miles, and the destination is 2,000 vertical feet above the start, it will take you 3 hours ÷ 2 hours = 5 hours. This formula allows for normal rest stops.

The main reason for having a compass is to orient your map— to position it so that north on the map is north on the ground.

Fig 11-1

Fig 11-2 Topographic map oriented with compass

First, place your compass on the map with north on the compass pointed toward the top of the map. Then check the magnetic declination shown on the bottom margin of the map. For instance, in the High Sierra the declination is roughly 17 degrees east of north. In other words, in the Sierra your compass needle will point about 17 degrees east of true north. To orient the map, rotate the map, with your compass on it, until your compass needle points 17 degrees east of true north.

Once you start hiking, check the map every mile or so to see where you are on it. Compare the map with what you see around you. Soon you will discover how a feature of the landscape, such as a peak, looks on the topographic map. You will discover that where contour lines cross streams, they make arrowheads pointing upstream. You will discover that where there are cliffs, the contour lines on the map are very close together. Eventually, you will be able to look at any part of a topographic map and get a pretty good idea of what that area actually looks like—if you practice.

When you can match map and actual terrain in your head, you are never lost. Using your compass—sometimes even without using it—you can choose and follow a route from A to B that you think would be interesting, or perhaps even easier than the trail route.

One other habit is very helpful in finding one’s way around the wilderness. It might be called “hindsighting.” As you hike, periodically turn around and look back at the country you have passed through. When you retrace your steps, the memory of these glimpses will help guide you.

A Forest Service map supplements a topographic map by (usually) showing more recent trail alignments than the topographic map shows. Alas, the Forest Service map also shows more recent logging roads.

Finally, a good road map will help you in driving to the trailhead. There are no perfect road maps, but those of the American Automobile Association and its state affiliates are the best. Do not, however, rely on them for roadless areas.

PREV: Safety and Well-being

NEXT: Equipment Care

All Backpacking articles

© CRSociety.net