1. Assess Your Measurements

2. Buy Your Materials

3. Buy the Extras

4. Deal with Preliminaries

5. Examine the Pattern

6. Adjust the Pattern

7. Try on the Pattern

8. Plan the Pattern Layout and Pin

9. Cut out the Garment

10. Transfer the Markings

11. Assemble for First Fitting

12. Make up the Garment

1. ASSESS YOUR MEASUREMENTS

The basis of every well-made garment is the fit. As we have already seen, it's essential to choose the correct pattern size.

Some women find one make

of pattern suits them better than another because it conforms more nearly

to their figure type. Some find that the average paper pattern needs no alteration.

But most of us, even when we have chosen the best size of pattern, have to

do a little adjusting.

The time to do this is on the paper pattern, and not once the garment is cut out. So let us begin by drawing up a complete measurement sheet. Many people taking dressmaking lessons for the first time are amazed to find how many measurements there are to take, far more than the simple bust, waist, hip and back waist length which determined the pattern size.

Taking measurements is one job where it's best to have some help. If there is no—one at home who can give it, you may find that you can ask for assistance in the paper pattern department, or in a shop specializing in sewing aids. Often the sewing machine representatives are highly-trained in home dressmaking, and some can be very helpful.

I can't stress strongly enough how important it's that the measurements which are taken should be accurate down to the last detail, for on this depends the success of the finished garment.

You could use the personal measurements chart that follows to form the basis of a sewing notebook. Buy a child’s strong scrapbook, copy the complete chart into the front of it, and follow it with details of each garment as you make it. For each one you could include the pattern envelope, leftover scraps of fabric for future matching or patching, odd buttons left over, perhaps notes of the accessories you wear with the garment.

If your measurements change radically, you can write out the chart again, filling in the revised measurements.

It will be a fascinating record of your hobby.

YOUR COMPLETE MEASUREMENTS CHART |

|

|

Name___ Date___ Height ___.ft. in. Weight with minimum clothes ___

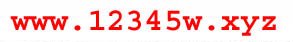

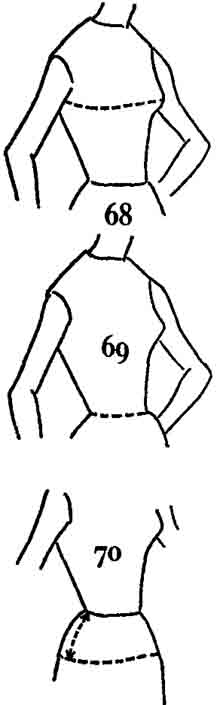

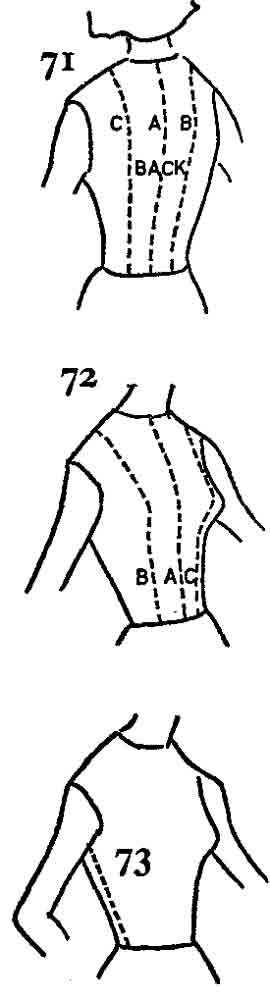

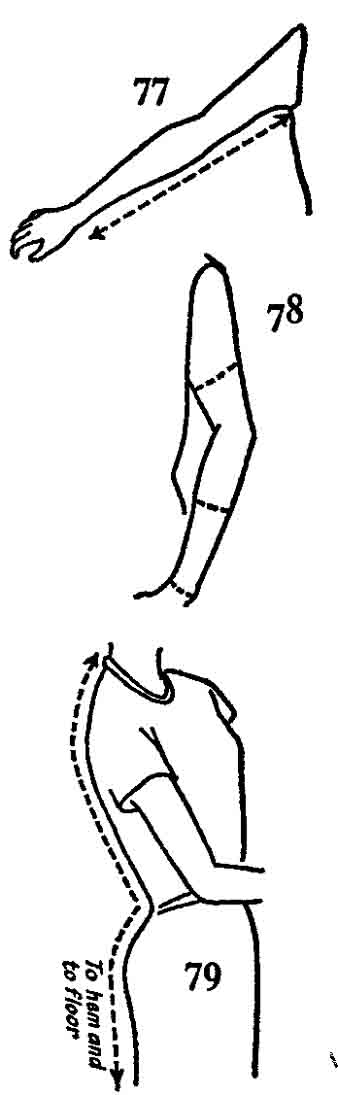

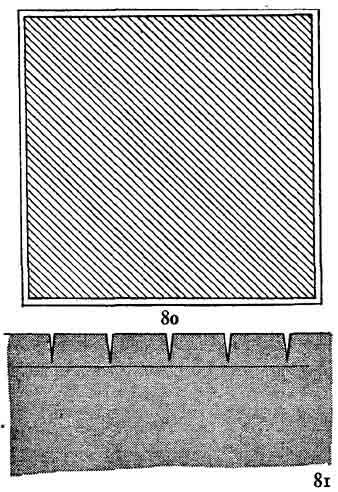

*1. BUST (68) This measurement is taken by your helper, standing behind you. It should take in the fullest part of the bust and go slightly higher at the back to include the shoulder blades. *2. WAIST (69)* To locate your natural waistline, tie a cord round your waist at the narrowest part. Then measure: (a) the entire waist. (b) across front of waist, from side seam to side seam. Leave cord in place for the rest of the measuring if you wish. *3. HIPS AT FULLEST PART (70) You can establish which is the fullest part of your hips by trying the tape measure at various distances below the waist. Having found where your hips are widest, use the other end of the tape measure to find the distance from your waist down to the tape measure. Thus in future you know how many inches below your waistline your hip measurement should be taken. (The average is 7—8 in. below the waistline.) *4. BACK BODICE LENGTH ( (A) centre back bodice length. This measurement is taken from the neckline down the centre back to the waistline. (B) shoulder to waistline, right side. (C) shoulder to waistline, left side. This measurement is sometimes referred to as ‘back waist length’. *5. FRONT BODICE LENGTH (72) (A) center-front length. This measurement is taken from the neck line straight down to the waistline. (B) shoulder to waistline, right side. (C) shoulder to waistline, left side. *6. SIDE BODICE LENGTH Measure underarm to waistline, right side and left side. These measurements are taken while you stand with your hand resting lightly on your hip. The top of the underarm seam is taken from a point z in. below the armpit. Measure both sides of the body to check any differences. 7. SHOULDER (74) (A) shoulder line, right.__ R (B) shoulder line, left.__ L Measure each shoulder as if along a shoulder seam, i.e. from the base of the neck (on the side) along the shoulder to the point of the shoulder. Take particular note of any difference in the two measurements. 8. SHOULDER TIP TO SHOULDER TIP (75) Your helper should measure straight across the top of your back, from shoulder to shoulder, while you clasp your hands together in front, at waistline level, with arms forward and slightly raised. 9. BACK WIDTH, ARMHOLE TO ARMHOLE (76) Your helper should measure from armhole seam to armhole seam, 4 in. below neckline. Hands should be clasped and arms forward as above. 10. SLEEVE LENGTH (77) (Check both arms) (A) point of shoulder to point of elbow (arm bent). (B) Point of elbow to wrist (arm bent). (C) inside arm from underarm seam, 1 in. below armpit, to wrist. This measurement is taken with the arm stretched straight. 11. ARM (78) (Check both arms) This measurement is taken round the bare arm in three places, with arm straight: (A) wrist. Measurement should include wrist bone. (B) lower arm, about halfway between elbow and wrist. (C) upper arm, about halfway between shoulder and elbow. 12. SKIRT LENGTH (79) (A) neck to floor. (B) waist to hem. You will know which hem length you like to wear, and naturally this will fluctuate from time to time. Note: If you make clothes for various members of the family, write out and complete a chart for each. If updated regularly, it can give you a useful year— by-year record of the sizes of growing children. * These are the four measurements most crucial in your choice of pattern size. |

2. BUY YOUR MATERIALS

Never buy fabric until you have checked the exact yardage specified for your size on the pattern envelope. Buy exactly the amount of fabric called for.

It may seem to you, as you make more and more garments, that the pattern companies are over-generous with the amount of material they specify, and you may feel sure that you can manage with less. Do remember, however, that pattern layouts have been worked out by experts, and that they take into account many factors including the ‘grain’ of the fabric and the cut of the garment. It is quite possible that if you devised your own pattern layout you could save half a yard of fabric, but it simply isn't worth making such a small saving when you might ruin the whole look of your garment and so waste all the hours you have put into making it.

Most of the reputable manufacturers include a paragraph headed ‘Suggested Fabrics’ on their pattern envelopes. If home dressmakers always took the advice given, quite a few costly mistakes could be avoided. On some you may find statements such as ‘Do not use fabric with a diagonal stripe or a decided diagonal weave’ or ‘The above yardage doesn't allow for shrinkage or for matching stripes or plaids’. Never ignore them. It takes extra fabric and extra expertise to cope with matching up plaids and stripes.

Fabrics, fibers and finishes are dealt with in more detail in Section 6, and there you will find sewing notes, details about the properties of the various fabrics and fibers, and notes on their washability.

3. BUY THE EXTRAS

When you have bought your pattern and a suitable length of fabric, turn to the pattern envelope again to see what ‘sewing notions’ you will need.

On any good pattern these will be listed quite specifically: for example hooks and eyes, inter facing, zipper and seam binding. It is sensible to choose these when you choose your fabric, in order to ensure a good match. In addition, of course, you will need sewing thread—cotton, mercerized cotton or a synthetic thread, depending on the fabric. It is best to buy it in a shade slightly darker than the fabric itself. You will need two spools to complete the average garment.

4. DEAL WITH PRELIMINARIES

Once everything has been purchased, you will probably be in a hurry to get back home and start cutting out the new garment. But before you do so, check the following.

EQUIPMENT

Make sure you have at least the essentials for good dressmaking. Sewing aids are described in detail in Section 1.

You will certainly not be able to manage without dressmaking shears, a tape measure, dressmaker’s pins and an iron for pressing. If you have a wider selection of equipment, the work will be much easier.

FABRIC PREPARATION

You must find out whether it's necessary to pre-shrink the material you have bought before making it up. Most good cotton fabrics are pre shrunk, and more and more woolen fabrics are too, but if you are in any doubt at all, make a shrink test.

Lay the pattern out loosely on the material, following the layout guide on the pattern’s instruction sheet (see step 5, p. 6o). Cut out a square of fabric about 3 in. by 3 in. which you are sure would be wasted after the cutting-out proper. Do not cut the square too near any pattern piece. Now cut a piece of paper — ordinary writing paper will do—exactly the same size as your square.

Soak the square of fabric in water, roll it in a towel, and then press it lightly with an iron, using a damp pressing cloth and choosing a suitable iron setting for the fabric. This is important, for if you use an excessively hot iron on some fabrics, they may shrink for the wrong reasons.

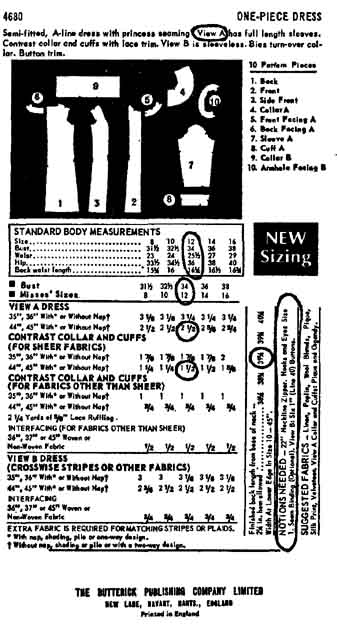

Next, compare your fabric sample with the paper square. If they are still identical in size you have no cause for concern, but if the fabric sample is now appreciably smaller (8o) there will be no alternative but to remove the pattern pieces from the material and shrink the whole length of fabric, snipping the selvedges first (81) to ensure that the fabric finds its correct dimensions. Selvedges, incidentally, are the narrow woven borders on the lengthwise edges of the fabric.

How do you shrink the fabric in the piece? If it's cotton, you can immerse it in hot water, and hang it to drip-dry before ironing it with a steam iron, or with a dry iron using a damp pressing cloth (82). If it's a wool fabric, simply press it all over, using a very damp pressing cloth and a steam iron if available. Work over each section slowly and carefully, pressing the iron down and then lifting it, rather than sliding it along.

Do not press-in the lengthways fold of the fabric. Whatever its type, it's best to open out the fabric for pressing and refold it afterwards for positioning the pattern pieces.

5. EXAMINE THE PATTERN

When you have opened the pattern envelope, the first thing to turn to is the instruction sheet. If you have chosen a pattern made by a reputable manufacturer, the instructions will be an in dispensable help to you in making your garment. Cheap patterns may contain thoroughly inadequate and sometimes even misleading advice.

However, even the best instruction sheet can't give a complete sewing lesson. The pattern company has to assume that the customer already has a basic knowledge of sewing and sewing language. Which is, of course, what this guide aims to give you.

When you first look at the back of the pattern envelope, and then at the instruction sheet, you may feel overwhelmed by the diversity of instructions. But there is a simple way to make things easier for yourself.

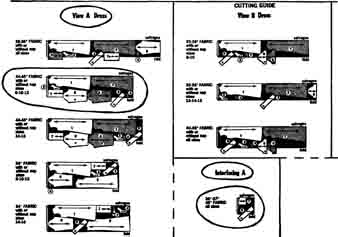

Take a pen, or a brightly-colored crayon or felt-tipped pen, and mark on the back of the pattern envelope details which apply to you (83). Ring round the version you are making, and the yardages, both for fabric and interfacing, which apply to your size. Ring round the body measurements which apply. Underline or ring round any sewing notions you will need.

Now turn to the instruction sheet. With the help of the diagram it includes, check that none of the pattern pieces is missing from the packet.

83. Marking the pattern envelope.

84. marking the instruction sheet.

84. marking the instruction sheet.

While you are doing this, sort out the pieces which apply to the version you are making, and put all the others away in the pattern envelope to avoid confusion.

Next turn to the cutting layouts on the instruction sheet. If there is more than one version of the pattern there will probably be a separate cutting layout for each version. There will almost certainly be different cutting lay outs depending on the width of fabric chosen (it may be 36 in., 45 m. or 48 in. width fabric for example). There may, moreover, be different cutting layouts for different pattern sizes. Work out carefully which cutting layout applies to you and put a ring round it (84); then look to see whether there is another layout for linings or interfacings for your version. If there is, put a ring round this (or these) too.

It really is worth taking a few minutes to do this marking up. It makes cutting out seem a much less formidable task to the beginner. When you have done it, you are ready to begin making any necessary adjustments to the pattern to fit your figure.

6. ADJUST THE PATTERN

When you have a complete log of your measurements you will be able to tell whether you need to make any adjustments to the pattern.

If your main measurements correspond exactly with the pattern you have purchased, you may, possibly, not need to make any adjustments. However this can't be taken as a foregone conclusion, for it may be that not every measurement corresponds. If you are above or below average height, or vary from the standard pattern measurements in one or more respects, some alteration will be essential, even though you have chosen the correct pattern size for your figure.

Your next step, therefore, is to check the measurements of the main pattern pieces against your own body measurements, to see whether or not they correspond.

Always remember that the measurements denoting the size of a pattern are standard measurements, not actual measurements of the pattern pieces. Take for example a pattern described on the envelope as 34 in. bust. This doesn't mean that the bodice when made up will measure exactly 34 in. at the level of the bustline. If it did, the garment would be very uncomfortable, pull across the figure, strain and possibly split with every movement of the body. Pattern manufacturers allow for a certain amount of ‘ease’ in every garment, so that the actual size of the bodice for a 34 in. figure may be 36 or 37 in. or more, depending on the style of the garment. Similarly a certain amount of ease is allowed for waistline and hipline. So when comparing the actual measurements of the various pattern pieces with your actual body measurements, you must always remember to allow for the extra inches given for ease by the pattern manufacturer.

APPROXIMATE EASE ALLOWANCE:

Bust |

3 ½ in. over the bust measurement in most dresses. Evening dresses designed to fit tightly in the bodice may have less ease allowance—as little as ½ in. in a strapless dress. |

Waist |

½ in, approximately. |

Waist |

2 ½ in. approximately on slim skirts. |

Back waist length |

¼ in, to 3/8 in. approximately. |

Here is a general guide to the ease which the leading pattern manufacturers allow. Do not, however, rely on it: check with the pattern book if the actual paper pattern doesn't give any guidance. Ease allowance can vary not only from one manufacturer to another, but also from garment to garment.

I would stress that these ease allowances should not in any way affect your thinking when you select your pattern size. If your bust size is, say, 34 in. then you choose a 34 pattern. The only time you need to think about ease allowance is when you are checking a paper pattern against your own body measurements.

HOW TO CHECK THE MEASUREMENT AGAINST EACH OTHER

Sort out the main pattern pieces for the bodice, skirt and sleeve.

Turn to item 1 of your personal measurement chart and copy down your bust measurement on a spare piece of paper or a clean page of your sewing notebook. After it write “Plus ease allowance of …” (see notes on previous page with regard to amount of allowance for ease).

Now measure the actual paper pattern measurements. Take all the pieces which go to make up the bodice. In the average pattern there will probably be only two—the back bodice piece, which may be a half-pattern only and require you to place the centre line to a fold of fabric when cutting out, and the front bodice piece, where you will probably be instructed to ‘Cut two’.

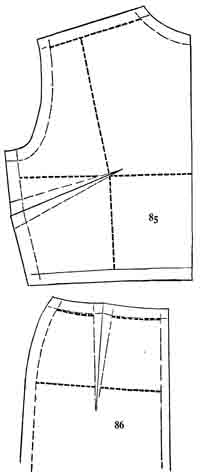

Whatever form the pattern pieces take, the object is to find out what the garment will actually measure at various points when made up (85 and 86). So when you, say, measure round the bustline of the pattern piece, be sure you don't include seam allowances, darts or any other pieces of fabric which will be missing when the garment is made up.

If you are keeping a dressmaking notebook, note it down neatly like this.

Pattern No ... by … size …

Bust

Actual measurement (taken from personal measurement chart) … in.

Plus ease allowance of … in.

Total … in.

Paper pattern measurement, actual … in.

Adjustment needed: Add (or deduct as the case may be) … in.

To do the job properly you should go through all twelve items in your personal measurement chart, checking each measurement carefully.

Just to recap, don't forget, when measuring the pattern pieces:

(a) To allow for the standard seam allowance widths—normally 5/8 in.

(b) To allow for any darts if they intersect the line which you are measuring.

(c) To allow for the extra inches given for ease in the paper pattern.

ALTERATIONS

When you have checked all the items in your personal measurements chart you will know whether or not you need to make alterations to the pattern pieces.

Sort out any pattern pieces which need altering.

Many good paper patterns provide clear instructions on each pattern piece, showing you where to make any increase or decrease in size. There will be lines to show you where to take a tuck in a pattern which is too long, and where to cut the pattern piece if you need to insert extra paper to increase the size.

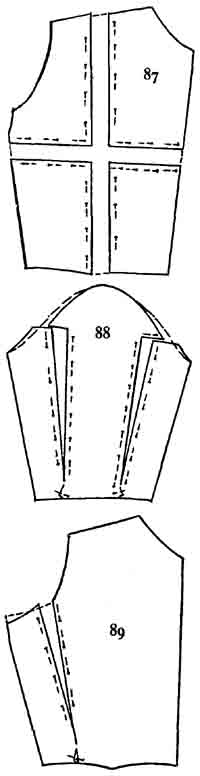

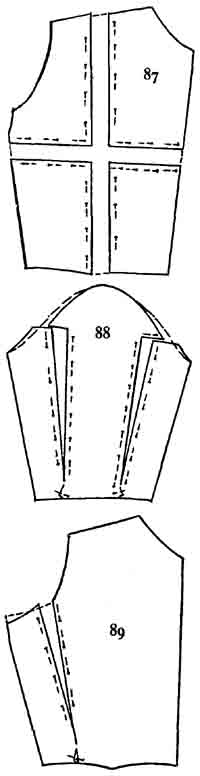

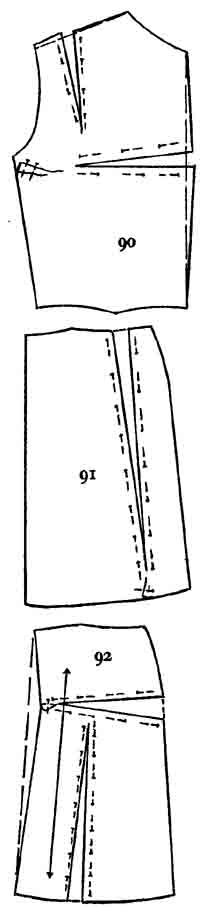

What do you do if the pattern gives you no guidance? To help you make the necessary adjustments I have taken a selection of typical figure problems and given the way to alter the pattern to find a solution (87 to 92). Glance through the sketches and you may find a way to adapt the pattern to your figure

If you have to increase the measurements of a pattern piece you will need some spare paper— tissue paper or greaseproof paper is suitable — to reinforce the altered pattern. Even if you have to make the measurements of a pattern piece smaller, you may still need spare paper, because the outline of the pattern piece may need neatening after the piece itself has been slashed.

Whatever the alterations, make sure that the pattern piece is still completely flat when you have pinned it. If there is a hump in it, the surplus paper must be folded into a tuck and pinned flat.

When you have finished altering the pattern pieces, check the measurements again to make sure that they correspond (apart from deductions) with those on your personal chart. Then to make sure your alterations are permanent, secure them firmly with adhesive tape.

7. TRY ON THE PATTERN

After any alterations to individual pieces have been made, give yourself a pattern fitting. To do this you pin together the main pattern pieces so that you can try them against your figure.

First pin the bodice sections together, remembering to pin in place any darts or tucks, and to make allowance for the seams.

Then pin together the front and back skirt sections, again remembering to take in darts and gathers. Finally pin bodice and skirt together. You will, of course, have only half a paper ‘garment’ but it will still be a very good guide.

Try the ‘garment’ on. Stand in front of a full-length mirror, relaxed and in a natural position, and examine the fit carefully. If possible enlist the help of someone able to give constructive criticism.

Look carefully at the shoulder line and the neckline. They are crucial to the fit of the garment, especially if the neckline is a fairly low one.

87. FULL BUSTLINE: Cut pattern from shoulder to waist and straight across bust-line. Put tissue paper underneath and pin to give the extra measurement needed. Take in extra width at waistline and underarm by increasing size of darts, and form a shoulder dart so that shoulder-line corresponds with back bodice.

88 and 89. HEAVY UPPER ARM: Slash bodice as shown (88) and spread to give extra width round armhole opening; pin tissue paper underneath to secure. Slash sleeve piece (89) on each side and open Out to correspond with armhole opening. Pin to tissue paper. Remember that sleeve cap will still need to be larger than armhole opening to allow for correct setting-in.

90. ROUNDED SHOULDERS, STOOPING Posture: Cut pattern as shown to give extra back bodice width; pin to tissue paper. Redraw centre back line clearly, to keep it straight with grain of fabric. Try on bodice pieces before making up, and use darts to accommodate any excess fabric at the shoulder-line. 91. THICK WAIST. Slash skirt pieces as shown and open out to give extra width needed. Increase bodice pieces to fit.

92. FULL SEAT. Cut pattern and open out as shown. Pin tissue paper underneath to make new centre back line, still straight with grain of fabric. If you don't wish to make skirt fuller at hemline, lay a fold in pattern midway between lengthwise slash and side seam, tapering it towards hipline. |

Look at the bustline. Does the point of the part finish below your bust, giving you a droopy look? Try re-pinning the pattern piece so that the dart finishes just below the point of the bust, and if this makes a noticeable improvement mark the change on the pattern with pencil or pen.

If, on the other hand, the point of the dart finishes too high, giving the bodice pattern piece a taut, flattened look, re-pinning the dart lower down may bring about a great improvement.

Look at the waistline. It is most important that it should fit snugly into your natural waist line. Check that there is enough width in the hips and waist, and re-pin if necessary.

Only when you are really satisfied with the pattern should you take the sections apart, marking the alterations clearly with a crayon or felt-tipped pen.

You may consider that you can dispense with the foregoing, quickly cut out the garment, and make it up in an evening. Some of the guidance I am going to give on pinning and tailor’s tacks may seem over-cautious, too. Indeed, some people do work very speedily with very few preliminaries. However it's only fair to say that these people usually fall into one of two categories. They are either so experienced after years of making their own clothes that they automatically know when to allow a little here and there, or else they are by nature inclined to cut all possible corners. The result in the latter case (and sometimes, alas, in the former too) is that their clothes never have a professional finish: they fit badly and look home-made.

If you talk to anyone who has worked in a top couture house you will discover that a staggering amount of care is lavished over every inch of a couture garment. They may be among the most highly—skilled seamstresses in the world, yet they would never dream of trying to cut corners in their work, and they would never rush to complete a garment in a couple of afternoons. Think of this when you are next in the middle of dressmaking, and find the attention to detail a little tiresome. Become your own couturier, be a perfectionist. Once you have acquired the routine, the preliminary work will seem a matter of course. You will hardly notice it.

8. PLAN THE PATTERN LAYOUT

Now take your fabric and begin pinning out the prepared pattern pieces, carefully following the sections of the layout guide you have circled.

Find out whether any of the pattern pieces should be placed to a fold, note how many pieces should be cut from each pattern, and make sure that each piece follows the grain of the fabric (arrowed lines on the pattern pieces will guide you). Place pins at right angles to the outside edge of the pattern, and use plenty of them to keep the pieces firmly in place.

Do not cram the pattern pieces on to the material so closely that you lose a little of the seam allowance in places. On the other hand, don't spread them out so much that you run out of fabric. You should not take pattern pieces right up to the selvedge edge or you may spoil the hang of a garment. Once the whole garment has been pinned out, it's best to cut off the selvedge edge—but not before then, or you will not be able to check the grain lines.

How do you check the grain lines? Every pattern piece bears a line which shows you the way the piece should be positioned on the fabric if the garment is to hang correctly. You can check that a pattern piece follows the correct grain of the fabric by making sure that the grain line on the pattern is parallel with the selvedge edge of the fabric. Pin the pattern piece in position, then measure the distance from the grain line, first from one end, then from the other, to the selvedge. The measurements should be identical: if they are not, unpin and start again.

Be sure you don't cut a single strand of fabric until every pattern piece is firmly pinned in position, all directions have been carefully read, all grain lines checked, and you are certain you haven't planned for two right sleeves, for example, or facings that face the wrong way, or a skirt with one panel using the wrong side of the fabric.

Try forming a mental picture of each piece as it will be when made up and in position. It is so easy to make mistakes. Errors spotted at this stage will save you a cartload of frustration, not to mention expense.

9. CUT OUT THE GARMENT

When everything has been checked, begin cutting. Hold the scissors with your thumb in the smaller ring and your first three fingers in the larger ring, and cut in long, smooth strokes with the full length of the scissors. The lower blade should rest on the table while you cut, and your other hand should rest firmly on the pattern.

If the cutting out is being done properly the shears will make a satisfying scrunchy noise of metal sliding smoothly against wood—a noise, I may say, that never fails to give me a thrill of delight at cutting into new fabric.

Take care not to lift the fabric and pattern from the table, or you may distort the shape of the piece you are cutting out.

In sorting the pattern pieces you will have noticed the v-notches which occur at frequent intervals round the edges. These are to enable you to match up the different pieces of the garment with precision. These notches will have to be transferred from the pattern to your fabric, so that they act as guides once the paper pattern has been removed. I will be dealing later with the transferring of markings, but there is a special point to make about the v—notches: it's best not to cut the ‘v’ inwards, into the seam allowance. This could seriously weaken the seam, especially if you accidentally cut too far. A much better way is to cut the ‘v’ outwards into the waste fabric ( so that the piece appears to have v-shaped tabs. When the garment has been seamed up, you can if you wish snip off these surplus v-shapes.

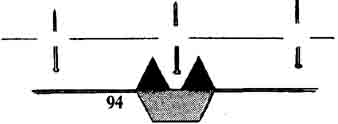

Incidentally, if there is a double v-notch marking, it's not necessary to cut two tabs close to each other. Instead cut one long tab shape, as in 94. It is much quicker and just as accurate.

If a pattern piece is to be cut on a single thickness of fabric and has to be repeated, remember that it must be turned over so that the pattern is cut for both sides of the body (otherwise you may find yourself with, say, two left sleeves or two right skirt panels).

As you cut the pieces out, lay them neatly in a pile. Do not take out the pins yet. Next cut out any facings and interfacings, linings and trimmings required.

When you have finished, gather up all the waste pieces of fabric and sort out and throw away all those which are too small to be useful. Other pieces can be kept. A few could be re served for your sewing notebook, the rest rolled up in a bundle, tied with a strip of material and saved for test pieces for machine stitching and perhaps practice buttonholes.

One good piece can be put into the pattern envelope, in case a spare piece is needed for repairing the garment or matching up accessories.

Clear away everything which will not be needed before you begin the next stage.

10. TRANSFER THE MARKINGS

Many home dressmakers who are self-taught have become so used to thinking that pattern marking is a waste of time that they automatically ignore the circles, v’s and diamond shapes which are included for guidance.

If you do this, now is the moment to think again. The markings have been put there by experts, and it's most unwise to ignore them. Never before have paper patterns been so clearly marked to guide you away from pitfalls.

I personally find that the best method of pattern marking is to make tailor’s tacks with special tacking thread, but many people like to use a tracing wheel in conjunction with dress maker’s colored carbon paper, or a small device which transfers the markings with chalk. If you have a sewing machine of the latest type you may be able to make special tailor’s tack stitching with this.

It is best for you to try as many methods as possible and then make your own choice as the need arises, for sometimes one marking method is better than another for the particular fabric with which you are working.

TAILOR’S TACKS

If you do decide to make tailor’s tacks, use one color tacking thread for the seamline markings and the centre back and front, and a different color for marking darts, pleats and button holes. This will mean that once the paper pattern is unpinned and the pieces of fabric are separated, you will still be able to tell instantly what the markings mean.

To make a tailor’s tack, thread your needle with tacking thread, using a length sufficient for sewing comfortably with the thread doubled. Do not make a knot in the ends. Now take a small stitch right through the centre of the pattern perforation or the centre of the dot, depending on the type of pattern. Make another stitch through the same spot, but leave a loop and two long ends If you are using a perforated pattern it will be possible, when you are ready, to lift away the tissue from the fabric, leaving the tailor’s tack in position. With a printed pattern, however, you will have to snip the loop of thread before the pattern can be removed.

Leave the pattern in position until all the tailor’s tacks have been made. If you wish, you can sew more than one tailor’s tack with the same length of thread, provided you take care that the pattern isn't pulled out of position. The threads linking different markings should be snipped before the pattern is removed.

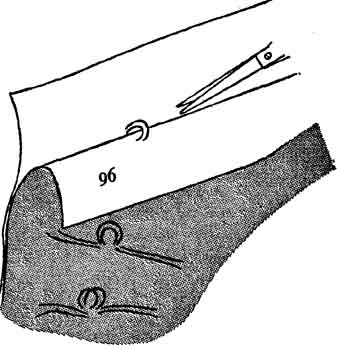

Once the markings have been transferred, put the pattern piece and fabric aside, laying them out flat, and turn to the next piece. When all the marking has been done, it's time to begin to remove the paper patterns, and then separate the layers of fabric. Do this carefully, one tack at a time, clipping the threads between the two layers (96) in order to leave a few strands of tacking thread in each layer of fabric.

Now put all the pattern pieces back into the pattern envelope, folding them carefully.

MARKING WITH CHALKED THREAD

Some dressmakers who use tailor’s tacks like to chalk the thread beforehand by drawing it round a block of tailor’s chalk, or even a piece of white blackboard chalk. This leaves a small deposit of chalk on the fabric and should the tacking thread be accidentally pulled out, the chalk ensures that the mark is still visible.

MARKING WITH CHALK ALONE

This isn't a reliable method for the home dressmaker. Accurate transfer of the markings is difficult, and the chalk marks may easily be rubbed away during the making up of the garment.

USING A TRACING WHEEL

Some fabrics react better than others to this method of marking. It works particularly well on taffeta, linen and plain materials, but should not be used on white or pastel-color fabrics, or on sheer fabrics.

The tracing wheel is used in conjunction with dressmaker’s carbon, which can be bought from any good department store. Choose the color closest to your fabric color, and test it on a scrap of the fabric before marking the whole garment, to make sure that the markings don't spoil the right side of the fabric.

To transfer markings, slip the carbon paper underneath the pattern piece, face down, so that the markings will transfer on to the wrong side of the fabric. If there are two thicknesses of material to be marked, as there normally will be, place another piece of carbon paper with the marking side upwards, beneath the lower layer of fabric, so that these markings will also transfer on to the wrong side of the fabric. You will probably have to remove a few pins in order to put the carbon paper in position.

Place the garment piece on a smooth, hard surface, and using a ruler as a guide run the tracing wheel firmly along each marking. Do not press the wheel down too heavily, but just enough to make the markings clear. Where circles are indicated, use two short lines crossed at right angles.

As with tailor’s tacks, when all marks are transferred, fold up the pattern pieces and put them back in the pattern envelope.

1. ASSEMBLE FOR FIRST FITTING

Now comes the moment when you find out whether or not your work has been accurate: the moment to tack the main parts of the garment together and try it for fit.

First carefully tack any darts or tucks which are indicated in your pattern, working on a flat surface to avoid stretching or over-working the fabric. If you have made alterations to darts in your paper pattern these should, of course, have been marked up on your pattern and transferred to the fabric and you will be able to make the dart in just the same way as usual.

The correct way to deal with darts is given in Section 5.

Some patterns will indicate that a section of a seam—for example part of a sleeve seam—should be ‘eased’. See Section 5 for the correct way to do this.

If you are working with a stretchy, loosely- woven fabric, or have chosen a style which has many pattern pieces with seams on the cross, stay-stitching or taping any bias edges will help to retain the shape of the garment.

Now you are ready to tack together all the main sections of the bodice and skirt, making the tacking stitches strong enough to keep the garment in one piece during the fitting. Be sure to tack along the exact seamlines.

Owners of one of the sewing machines on which a tacking (basting) stitch is possible, may prefer to use their machine for tacking the pieces together.

Now try the garment on over a slip and a good foundation garment if you wear one. Wear the sort of shoes you will wear with the finished garment. Take another critical look in a long mirror, and again try to enlist an enlightened second opinion.

If you have done the groundwork correctly, your creation will fit perfectly, but if it doesn't , now is the moment to make the necessary final adjustments.

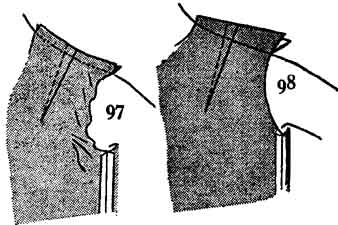

Perhaps the bodice fits badly, with crumpled parts where the fit should be smooth. It could be that you have a sloping shoulder line— sometimes one shoulder slopes more than the other—and you may need to increase the seam allowance on the shoulder line ( and 98) to correct the fault.

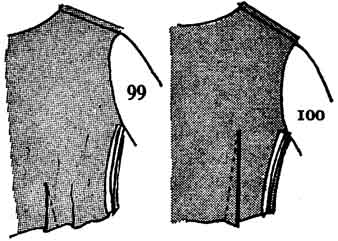

Perhaps you feel the waistline is a little too loose—in this case you can

increase the amount taken in by the dart, or make a second dart, to produce

the right effect and 100 ).

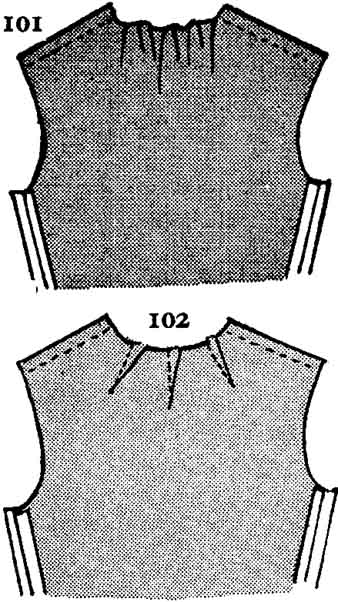

Perhaps the neckline fits badly, hanging away instead of fitting into the neck snugly. Darts may be the answer here too (101 and 102), but take great care that they are smooth and absolutely evenly spaced.

When you make an alteration of this nature, pin it first until you think you have the right effect, then tack and try on again, this time right side out. You may of course prefer to mark the changes with tailor’s chalk, rather than pins—and then tack them in place when you have taken the garment off.

At this stage alterations are usually necessary only because of slight irregularities in the figure, which should have been picked up earlier in the pattern-fitting stage.

When you are happy that all is as it should be, you will be almost ready to assemble the garment. Just take the pieces apart again—a moment’s job if you have a small unpicking tool (see fig. 23). Be sure to retain any alterations made, and carry the adjustments through to the finished garment.

If you are lucky enough to own a dress form you can, once you are sure that the fit is perfect, delegate fitting duty to this, and thus avoid the constant hopping in and out of a half-made dress.

The dress form, if exactly adjusted to your size, will hold the garment correctly and smoothly in place until you near completion. When you have to stop sewing for the day, put the garment on the dress form and slip a large plastic bag over it to keep it dust-free. If you have small children it would be best to use instead two large sheets of brown paper, pinned over the garment, since plastic can be extremely dangerous where there are young children about.

12. MAKE UP THE GARMENT Generally speaking, if you .have chosen a pattern produced by a reputable pattern company it's wise to follow the order of making up which they advise. But if you find the pattern sheet is inadequate or unintelligible to you, try this order of making up. It isn't by any means the only ‘order of work’—for that will always depend on the garment—but it gives a good general outline to making up a dress, and you can adapt it to other items.

1. Darts—pin, tack, stitch and press.

2. Bodice—pin, tack and stitch facings, centre front and back seams if any, shoulder seams, side seams. Press. Do not remove tacking stitches down centre front and centre back until garment is finished.

3. Special details—make buttonholes if any, set in the collar if any. Deal with pockets if any. Press as you work.

4. Sleeves—stitch, press and set in carefully. Press again.

5. Try on the bodice. Check the following:

* That the waistline seam falls at the natural waist.

* That the centre front and Centre back coincide with the centre of the figure.

* That shoulder seams are straight and set on top of the shoulder.

* That bodice darts are pointing directly to the fullest part of the bust.

* That the neckline fits smoothly, without gaping or pulling.

* That there is sufficient ease, especially across the back, for comfortable movement.

6. Neaten the armhole seams, and finish the sleeve ends or cuffs. Press as necessary.

7. Skirt. Complete the darts, then join the skirt pieces. If the skirt is gathered, take in the fullness.

8. Join the bodice to the skirt. Press and finish raw edges.

9. Zipper or other closure. Set in the zip fastener or other fastening.

12. Hem. Measure, pin, tack and stitch hem.

11. Neaten the garment. Neaten the inside seams and trim any loose threads; remove any remaining tacking stitches.

12. Add any finishing touches, for example buttons, hooks and eyes, pockets if not already added. Give a final press if necessary. Sew in a wash-care label if wished.